Abstract

The optimal goals in the surgical treatment of rectal cancer are curative resection, anal sphincter preservation, and preservation of sexual and voiding functions. The quality of complete resection of rectal cancer and the surrounding mesorectum can determine the prognosis of patients and their quality of life. With the emergence of total mesorectal excision in the field of rectal cancer surgery, anatomical sharp pelvic dissection has been emphasized to achieve these therapeutic goals. In the past, the rates of local recurrence and sexual/voiding dysfunction have been high. However, with sharp pelvic dissection based on the pelvic anatomy, local recurrence has decreased to less than 10%, and the preservation rate of sexual and voiding function is high. Improved surgical techniques have created much interest in the surgical anatomy related to curative rectal cancer surgery, with particular focus on the fascial planes and nerve plexuses and their relationship to the surgical planes of dissection. A complete understanding of rectum anatomy and the adjacent pelvic organs are essential for colorectal surgeons who want optimal oncologic outcomes and safety in the surgical treatment of rectal cancer.

Keywords: Rectal cancer, sharp pelvic dissection, rectal proper fascia, mesorectum, pelvic autonomic nervous system

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer is the third most common malignant tumor in the Western world. The recent, rapid increase in the incidence of colorectal cancer in Asia has been explained by the westernization of both diet and lifestyle. In the past, rectal cancer has been famous for its high rate of local recurrence, sacrifice of the anal sphincter, and sexual and voiding dysfunctions. During the last few decades, improvements in survival and reduced local recurrence have been observed. These are the result of more developed operative techniques and advances in multimodality approaches (including radiation techniques and new chemotherapeutic agents).

The aim of rectal cancer treatment is to reduce local recurrence and improve survival as much as possible. The control of local recurrence in rectal cancer treatment is crucial because of the associated effects on quality of life, pain, bleeding, and local sepsis. It is well known that the rate of local recurrence of rectal cancer is higher than for colon cancer; this is thought to be due to poor visualization of the surgical field, which makes anatomical dissection difficult. Subsequently, blunt dissection is usually done by hand. Surgery is usually performed within the deep narrow pelvic cavity with complex neuroanatomical structures in the vicinity. In the past, local recurrence has been reported as being as high as 30-38%; the frequency of sexual and voiding dysfunction has been reported as being high as well.1,2 In 1982, Heald et al.3 reported that local recurrence resulting from a small tumor cell nest remained in the mesorectum within 2 cm of the distal area of the tumor in rectal cancer. He concluded that a total mesorectal excision (TME), including the distal mesorectum, should be performed. It has been reported that after TME, the 5-year recurrence rate is 3.7%, and the 5-year disease-free survival rate is 80%.4 Subsequently published data also reported a markedly reduced rate of local recurrence and improved survival rate.5-7 The complications of sexual and bladder dysfunction after rectal cancer surgery can be avoided in the majority of patients by identifying and preserving the pelvic autonomic nerves. However, nerve damage can occur, such as cancer invasion of the nerve or excessive traction of the rectum in the deep, narrow pelvic cavity. There is literature concerning the high rate of the preservation of sexual and voiding function after rectal cancer surgery.8,9

An important concept in total mesorectal excision is sharp pelvic dissection based upon pelvic anatomical knowledge. This involves dissection of the rectum from the pelvic cavity under direct vision and removal of the mesorectum containing the lymph nodes and blood vessels surrounding rectal cancer as a one unit. A review of the literature regarding total mesorectal excision focused on several points. First, it concerned sharp dissection along the plane of the rectal proper fascia and excision of the rectum and surrounding mesorectum as one unit. In addition to these, the mesorectum enveloped with rectal proper fascia should be intact because the mesorectum can be damaged at the distal part of the mesorectum due to difficult dissection from narrow pelvis. Keeping this plane, the pelvic autonomic nerve can be subsequently preserved. Secondly, circumferential and distal resection margins should be obtained. There are many published reports regarding the prognostic significance of circumferential resection margin.10,11 TME has been accepted as a standard surgical treatment of rectal cancer for its favorable oncologic results and improvement of the quality of life in sexual and voiding function. Regarding the extent of lymph node dissection, mid or lower rectal cancer has a 30% chance of lymph node metastasis along the internal iliac artery and its branches. Many Japanese surgeons have advocated lateral pelvic lymph node dissection, which can improve survival rate at the cost of high postoperative morbidity.12,13 There have been some controversies regarding the oncologic benefits of lateral pelvic lymph node dissection.

Multicenter, multidisciplinary, clinical trials should be based upon the optimal surgical treatment with precise sharp pelvic dissection.

During rectal mobilization from the narrow and deep pelvic cavity, some acute complications (such as rectal perforation, bleeding, inadevertent ureteral damage, and damage to the pelvic autonomic nerves) may be encountered.

The following is a review of the surgical anatomical structures essential for sharp pelvic dissection. In addition, we include a discussion of technical tips for surgical treatment of rectal cancer based on cadaveric dissection and surgery cases studies of rectal cancer.

RECTUM

The rectum is located at the pelvic cavity. The lower third anterior portion is extraperitoneally located, while the posterior part is completely extraperitoneally located. Its length is about 12-15 cm. The rectal muscle wall is surrounded by a fatty layer which contains blood vessels, lymphatics, and lymph nodes (the so-called mesorectum). The rectum and mesorectum are enveloped by the endopelvic fascia. These structures contact adjacent organs, such as the prostate, seminal vesicle, posterior vaginal wall, and cervix of the uterus.

POSTERIOR DISSECTION OF THE RECTUM

First of all, it is very important to understand the fascial planes around the rectum and adjacent organ for sharp pelvic dissection. If pelvic dissection proceeds along the correct fascial plane, the operation can be finished without bleeding.

When dissection is performed posterior to the rectum, precise dissection must be performed into the retrorectal avascular space along the visceral pelvic fascia plane (the rectal proper fascia); this dissection plane hardly bleeds. Bisset et al.14 described a fibrous envelope surrounding the perirectal fat (which they named the fascia propria); it corresponded to the visceral pelvic fascia mentioned by Diop et al.15 The fascia propria is, in fact, of variable thickness (Fig. 1B).

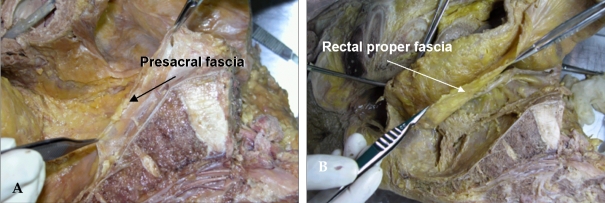

Fig. 1.

Cadaveric dissection of hemisectioned pelvis. (A) Presacral fascia covers the presacral vein over the sacrum. (B) The fascia picked up by the forceps is the rectal proper fascia enveloping the mesorectum and the rectum.

By avoiding inferior hypogastric nerve injury at the S4 level, loose areolar tissue between the presacral fascia and the rectal proper fascia is encountered.16,17 This fascia is known as the rectosacral fascia or Waldeyer's fascia. This fascia is formed by dense connective tissue between the posterior wall of the rectum and the third and fourth sacral vertebra. (Fig. 2) Crapp and Cuthbertson18 described this fascia in detail, pointing out its clinical significance based on the fact that failure to recognize and divide it may result in either perforation of the rectum or hemorrhage from presacral venous plexus. In addition, full mobilization of the rectum is not possible unless the rectosacral fascia is divided. The thickness of this fascia varies significantly between individuals. It may be thin and thus may tear readily. In thicker cases, blunt dissection by hand results in avulsion injury of the presacral venous system, which sometimes causes an uncontrollable large-volume hemorrhage. A poor visual field at the narrow true pelvic cavity led us to perform a blunt hand dissection, which is a dangerous point of avulsion injury of the presacral fascia (Fig. 1A).

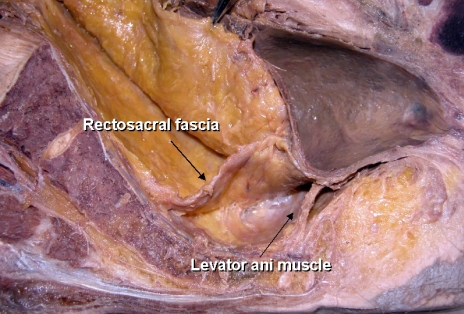

Fig. 2.

Cadaveric dissection of hemisectioned pelvis; the retrorectal space. The rectosacral fascia is noted in the retrorectal space at the level of 4th sacrum when dissection proceeds along the rectal proper fascial plane.

In addition to these clinical significances, sharp division of the rectosacral fascia helps pelvic dissection to reach down to the coccyx level, and the pelvic plexus can be visualized at posterolateral side of the pelvic wall.

MRI has become a more common tool in the preoperative staging for rectal cancer because it can give us much information, such as depth of invasion, regional lymph node status, distance of the tumor from the mesorectal fascia, and anal sphincter involvement, among others.

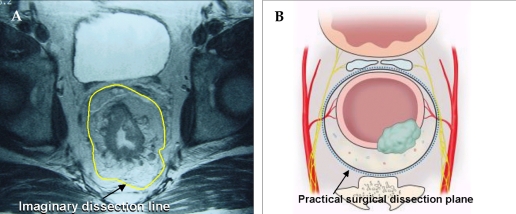

The dissection plane of TME appears as a fine, linear, hypodense structure on an axial T2-weighted fast spin echo image; this is the rectal proper fascia. Usually, an imaginary dissection line along the rectal proper fascia can be drawn on MRI (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

(A) The yellow line on the axial view of pelvic MRI is a imaginary line of sharp pelvic dissection along the rectal proper fascia (arrow). (B) A dotted line in schematic axial view is the loose areolar tissue plane between the rectal proper fascia and the parietal pelvic fascia. This line is the practical surgical dissection plane and can preserve the pelvic autonomic nerve without damaging to the mesorectum. The pelvic plexus is close contact with the fascia enveloping the mesorectum.

ANTERIOR DISSECTION OF THE RECTUM

In males, at the level of the seminal vesicle, pelvic dissection is usually met by Denonvilliers's fascia, a white membrane at the anterior part of the rectum. By incising this membrane, the rectum is dissected from the seminal vesicle. With further anterior dissection, bleeding and nerve injury may result. Denonvilliers wrote that there is a membrane behind the seminal vesicles and in front of the rectum. He reported that this membrane was not present in females.19 The consistency varies from a thin translucent layer to a tough thick membrane. It seems to be more prominent in young male patients. It is comprised of sense collagen, smooth muscle fibers and coarse elastic fibers.20 The rectogenital fascia is most often called "Denonvilliers fascia". Embryologically, Diop et al. hypothesized the existence of two different envelopes around the perirectal fat: a posterolateral envelope (made up of the visceral pelvic fascia) and an envelope at the anterior limit (a true recto-genital membrane made up of the "Denonvilliers fascia").

The Denonvilliers fascia should be opened on the lower part of its anterior aspect and dissected down its posterior aspect to avoid injury of the genito-urinary neurovascular bundles.

In addition, dissection and excessive traction of the seminal vesicle from the 10 o'clock and 2 o'clock directions might cause injury of the neurovascular bundle running to the genitalia. Practical technical tips were introduced by Heald. It has been reported that it is important to perform a U-shaped incision during the excision of Denonvillier's fascia in the anterior part of the rectum.21 It is important to avoid damage of the neurovascular bundle in the 10 o'clock and 2 o'clock directions to preserve sexual and voiding function.

Fibers from the pelvic plexus pass inferior to the seminal vesicles to enter the wall of the bladder. Nerve fibers located anterior to the fascia of Denonvilliers are at greater risk during an anterior dissection for lower rectal cancer. Lateral or anterior traction on the rectum and its fascia propria produces tenting of the pelvic nerves away from the postero-lateral pelvic wall. These result in temporary postoperative parasympathetic nerve dysfunction.22

If the tumor is located predominantly at the anterior part of the rectum, careful dissection should include Denonvilliers's fascia and sometimes seminal vesicles for curative resection. In females, if the vaginal wall is insufficiently dissected from the rectal wall during colorectal anastomosis, the vagina may be injured; therefore, the rectum and the vaginal wall should be dissected carefully and sufficiently. These are important technical tips for preventing postoperative iatrogenic rectovaginal fistula.

THE ANATOMY OF THE MESORECTUM

The rectum is surrounded by a layer of fatty tissue which contains the blood vessels, draining lymph vessels, and the lymph node of the rectum. This layer is referred to as the mesorectum. The mesorectum is defined by surgeons as the fatty envelope surrounding the posterior and lateral aspects of the retroperitoneal rectum. The visceral pelvic fascia is the postero-lateral envelope of the perirectal fat and is called the rectal proper fascia, as previously mentioned.18

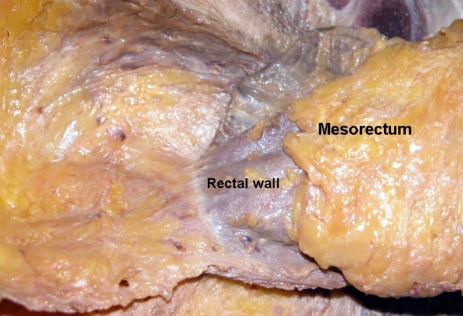

Total mesorectal excision should emphasize that mesorectum should be removed completely regardless the level of the tumor; however, there are still controversies about the extent of removal of the appropriate mesorectum. Based on histoptatholoigcal studies, rectal cancer did not spread to the distal mesorectum beyond 4 cm below the tumor level. Actually, the mesorectum is almost absent approximately 2 cm above the levator ani muscle, at that point, only the rectal wall remains (Fig. 4).14,15

Fig. 4.

The mesorectum is well developed at the posterolateral side of the rectum. The mesorectum is tapered down and it ended 2-3 cm above the level of the levator ani muscle.

The mesorectum disappears at the area of the attachment of the rectosacral fascia. Hence, in surgery for middle and lower rectal cancer, the standard has become the removal of nearly the entire mesorectum.

LATERAL MOBILIZATION OF THE RECTUM

The mesorectum is well developed in the posterior area of the rectum. Usually the rectal proper fascia surrounding the mesorectum is adhered to the pelvic plexus. If careful dissection is not performed at this area, the pelvic plexus could be injured or avulsion injury can ensue during excessive traction of the rectum in the narrow pelvic cavity. The attached area has been called the lateral ligament. Still, there are some controversies as to whether or not this area is a real ligamentous structure. Also, some bleeding was noted during dissection, because the middle rectal artery from the internal iliac artery runs through this point. Hoeer J et al.23 reported that the distance between the lateral rectum and the pelvic plexus is only 2-3 mm. The anterior rectum is almost directly adhered to the neurovascular bundle, separated by Denonvilliers' fascia. Sato et al.24 reported that the middle rectal artery was discovered only in approximately 34.9% of cases. Based upon personal experience, the middle rectal artery is usually present unilaterally, and its lumen usually small (less than 5 mm). Sometimes, however, thick arteries are encountered. Usually, I identify and clip these with a surgical clip under direct vision. During the management of this vessel, non-anatomical mass ligation and excessive traction cause injury to the pelvic plexus and sacral parasympathetic nerve arising from the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th sacrum. Afterwards, the rectosacral fascia is divided and dissection continues to the coccyx level. Next, anterior dissection is performed and the rectum is separated from the seminal vesicle. While avoiding excessive traction of the rectum posteriorly, the lateral part of the rectum is ready to dissect after anterior and posterior dissection. The pelvic plexus and arising sacral nerves can then be visualized. If the tumor is located close to the lateral part of the mesorectum, traction of the rectum and dissection from the pelvic plexus might cause breaching of the covering rectal proper fascia at the narrow true pelvic cavity. An experienced surgeon should be careful when managing rectal cancer at this level of dissection. If the tumor definitely invaded the pelvic plexus, it should be sacrificed. Sometimes, a fungating tumor located at the lateral part of the rectum directly invades the pelvic plexus and pelvic side wall. Yamakoshi et al.25 reported that preservation of the pelvic plexus for rectal cancer could shorten the distance between the cancer and the lateral resection margin. Therefore, they found that average distance between the muscularis propria and the pelvic plexus for both autopsied and surgical specimens were 8.3 mm and 14.7 mm, respectively. The pelvic plexus was located about 10 mm from the outer margin of the rectal muscularis propria. This observation led us to decide to resect the pelvic plexus concomitantly for curative resection if the middle or lower rectal cancer had invaded the rectal wall.

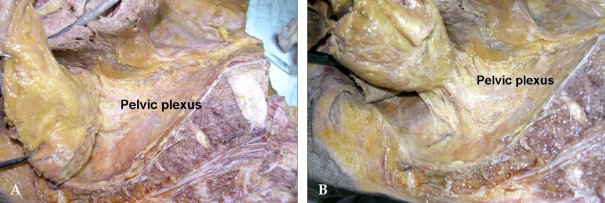

Cadaveric dissection with a hemisectioned pelvis shows that the rectal proper fascia is directly adhered to the meshlike pelvic plexus; this adhered portion can be regarded as a ligament (the so-called lateral ligament) (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

(A) The rectal proper fascia is adhesed to the mesh like pelvic plexus at the lateral pelvic wall. (B) The fine branches from pelvic plexus enter the rectal wall. The rectum was attached to the lateral pelvic wall by adhesed pelvic plexus.

I think that ligamentous-adhered structures between the mesorectum and the inferior hypogastric or pelvic plexus are present as very thin to tough, thick structures. They may consist of the rectal branches from the pelvic plexus, connective tissue, and the middle rectal artery in approximately 25% of patients. Based on personal experience, sharp pelvic dissection with minimal traction of the rectum reveals some branches of the rectal plexus and middle rectal artery (sometimes, unilateral); nothing as substantial as a ligament is cut. The rate of appearance of the middle rectal artery was determined by Wilmer (64%) and Didio et al. (46.7%).26,27 Sato pointed out that pelvic splanchnic nerves arising more posteromedially from the third and fourth sacral nerves can be considered a component of the lateral ligament. These observations had important clinical implications because rough traction and blunt dissection around these areas results in pelvic splanchnic nerve damage, which might lead to sexual dysfunction. Nano et al.28 dissected 27 fresh cadavers, beautifully describing the lateral ligament and its relation with the middle rectal artery and the nervi recti. They pointed out the lateral ligament as an extension of the mesorectum, anchoring it to the endopelvic fascia. In addition to these, the lateral ligament is in contact with the lateral neurovascular pedicle of the rectum. The point of insertion of the lateral ligament to the endopelvic fascia is dangerously close to the urogenital bundle.

Takahashi et al.12 defined the lateral ligament as a condensation of connective tissue around the middle rectal artery; they emphasized the importance of this ligament in the lymphatic drainage of the lower rectum.

Sharp pelvic dissection for rectal cancer emphasizes the direct visualization of these structures. Conventional methods for dealing with the lateral ligament, such as mass ligation and tough traction, sometimes result in incomplete total mesorectal excision and sexual dysfunction.29

The hypogastric nerve must be visualized over the whole length during retrorectal space dissection along the plane of the visceral pelvic fascia. This separation is initially median and then lateral as far as the pelvic plexus. Without excessive traction on the rectum, the dissection is continued laterally in contact with and medial to the pelvic plexus, while coagulating and dividing several small neurovascular bundles stretched between the pelvic plexus and the rectum. At the level of the seminal vesicle, the neurovascular bundle can be seen from the pelvic plexus running to the prostate at the lateral part of pelvic wall. Rectal mobilization at this point can cause nerve damage resulting in sexual and bladder function.

THE LEVATOR ANI MUSCLE

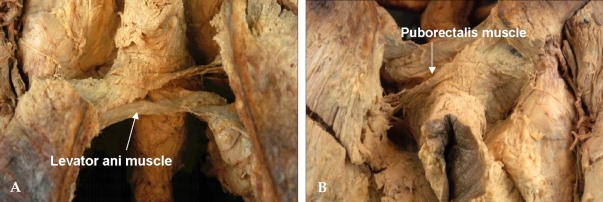

Levator ani muscle forms the pelvic floor. It consists of the pubococcygeus, puborectalis, and iliococcygeus muscles. (Fig. 6) These muscles actually insert into the pelvic sidewall, which is like a membranous sheet and sometimes adheres to the rectal proper fascia. The U-shaped puborectalis muscle is clearly seen, and the surrounding levator ani muscle is also seen.15 In an abdominoperineal resection, these muscles must be cut from their insertion sites.

Fig. 6.

(A) Midline of posterior side sacrum was divided and component of the levator ani muscle was shown. (B) U-shaped puborectalis muscle was shown around the rectum. These levator ani muscle must be cut off from its insertion site.

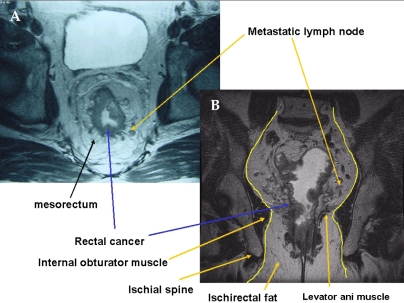

Specimens should be shaped as a cylinder. Pelvic MRI clearly shows the imaginary dissection line of the perineal phase (Fig. 7). The reason for the higher local recurrence of AbdominoPerineal Resection (APR) than for Low Anterior Resection (LAR) can be explained by the high incidence of cancer involvement of circumferential resection margin and subsequently high rate of local recurrence.

Fig. 7.

(A) Axial view of MR image shows a fine linear hypodense structure along the visceral pelvic fascia enveloping the mesorectum. (B) Coronal view of MR image shows a metastatic lymph node was located at close to the imaginary dissection line, especially the insertion site of the levator ani muscle.

PELVIC AUTONOMIC NERVE SYSTEM

In the past, disturbances of bladder and sexual function are well known sequelae of rectal cancer surgery. Bladder dysfunction consists of difficulty emptying the bladder and incontinence. Male sexual problems consist of erection dysfunction, absence of ejaculation, or retrograde ejaculation. Female sexual dysfunction has been reported as decreased vaginal secretion, dyspareunia, and decreased ability to achieve orgasm.

These sexual and voiding dysfunctions are most frequently secondary to sympathetic or parasympathetic nerve interruption.30

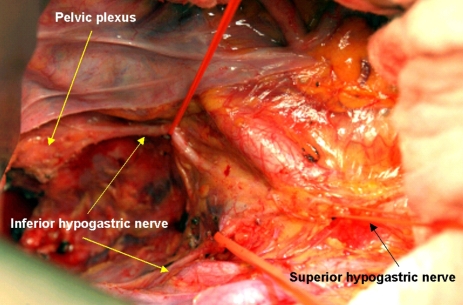

Three common sites of operative injury are the superior hypogastric plexus nerve, the inferior hypogastric plexus nerve, and the pelvic plexus.

Preservation techniques are important in preserving sexual and voiding function. To achieve these goals, it is important to understand the relation between the nerve and the pelvic fascia. Dissection should be performed along the loose areolar tissue between the rectal proper fascia and the parietal pelvic fascia. The nervous system usually runs along these planes. There are a couple of vulnerable sites of injury. The superior hypogastric nerve descends and forms a plexus in the vicinity of the origin of the inferior mesenteric artery. This plexus forms a dense network around the inferior mesenteric artery. Therefore, during dissection of the lymph node around the origin of the inferior mesenteric artery (IMA) or ligation of the IMA, the superior hypogastric nerve may be injured. If this area were injured, retrograde ejaculation develops. The superior hypogastric nerve descends to the pelvis by crossing the left common iliac artery at the level of the 1st sacrum and descends into the pelvic cavity along the pelvic side wall. During the separation of the mesosigmoid colon from the gonadal vessels and ureter, the superior and inferior hypogastric nerve plexuses must be preserved.

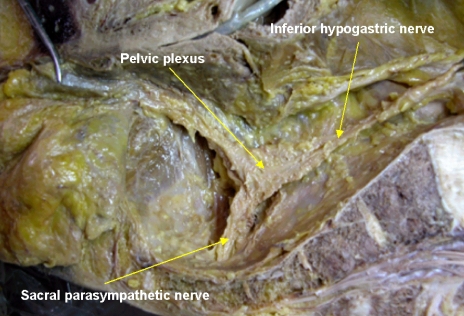

Pelvic dissection must be kept along the plane between the inferior hypogastric nerve fibers and the rectal proper fascia in the pelvic cavity. Sometimes, fine branches to the rectal proper fascia were noted and were vulnerable to cutting during dissection. Kirkham et al.31 reported that the inferior hypogastric nerves are usually more adherent to the visceral fascia covering mesorectum than the pelvic sidewall and lie anterior to the retrorectal space. These observations are one of the findings we often encounter during retrorectal space dissection. The inferior hypogastric nerve continues parallel to the ureter and internal artery in a caudal and lateral direction, reaching the pelvic autonomic nerve plexus at the lateral pelvic sidewall. The inferior hypogastric nerve forms the pelvic nerve plexus at the lateral pelvic wall by encountering the parasympathetic sacral nerve originating from the 2nd, 3rd and 4th sacral cavities. Small numerous neurovascular bundles running from the pelvic nerve plexus to the genitalia cross the seminal vesicle in the 10 o'clock and 2 o'clock directions. We observe a mesh-like structure on the lateral pelvic wall and it descends to the genital organ at the lateral tip of the seminal vesicle. Therefore, dissection should be done carefully around these areas. Walsh and Donker32 also reported that a useful marker for pelvic plexus midpoints is the tip of seminal vesicle in males. At the level of the seminal vesicle, the running neurovascular bundle along the seminal vesicle should be considered, and one must pay attention to the pelvic plexus arising from sacral foramen during rectal mobilization. In a hemisectioned pelvis, the T-shape nerve can be easily observed (Fig. 8). By closer observation with magnification, the parasympathetic nerve can be observed crossing the piriformis muscle, penetrating the pelvic fascia in the sidewall and the parasympathetic nerve originated from 2nd, 3rd and 4th sacrum, encountering the inferior hypogastric nerve and forming the pelvic plexus in the pelvic lateral wall. From the pelvic plexus, numerous nervous branches run to the urogenital organ (Fig. 5).

Fig. 8.

Cadaveric dissection on hemisectioned pelvis show the inferior hypogastric nerve descend into the pelvic cavity and meet sacral parasympathetic nerve arising from S2th, 3th, 4th foramen nearby the piriformis muscle. The inferior hypogastric nerve form the pelvic plexus at the lateral pelvic wall after merging the sacral parasympathetic nerves. Nerve bundles from pelvic plexus go to the genitourinary organ along the seminal vesicle in male.

Regarding injury of the pelvic plexus, the areas that should be handled carefully during mobilization of the rectum are the lateral wall of the rectum and the area where the pelvic plexus is attached. After successive dissection of this area, the rectum is delivered from the pelvic cavity. An actual quadrangular mesh-like structure (pelvic nerve plexus) is adhered to the rectal proper fascia surrounding the mesorectum. The parasympathetic nerve arises from the ventral roots of S3-4 and a rhomboid-shaped plaque of nervous tissue at the pelvic sidewall. The pelvic plexus is sometimes revealed as a matted rhomboid structure with dimensions of 4 cm by 2.5 cm, lying almost in the sagittal plane lateral to the rectum.33,34

The neurovascular bundle, described by Walsh and Schlegel, runs in front of the rectogenital fascia in the parametrium in females and in the space occupied by the seminal vesicles and the prostate in males.35 Hollabaugh et al.36 noted that most of the efferent nerves of the pelvic plexus perforate (what they called the endopelvic fascia and the genitourinary branches) ran along the prostate surface of Denonvillers's fascia.

I would like to reemphasize the avoidance of damage to the pelvic plexus and the neurovascular bundle to the genitalia during dissection. It is important to incise the rectosacral fascia first; the dissection must then go down to the coccyx and lateral wall of the rectum separated from the pelvic plexus. Around this area, proper traction of the rectum is important in preventing avulsion injury of pelvic plexus. Meticulous dissection should be performed on the fascia surrounding the mesorectum and the pelvic plexus must be separated carefully (Fig. 9). During dissection of this area, the middle rectal artery is sometimes encountered. It should be identified, divided, and ligated with a surgical clip. It is important to avoid mass ligation in this area to avoid significant bleeding for nerve preservation. Too much traction of the rectum may cause avulsion injury to the running the 3rd sacral nerve, which might result in male sexual function (such as erectile dysfunction). Usually, cutting the rectosacral fascia and opening the retrorectal space laterally reveals the nervi erigentes, with the S3 component usually being the largest.31,37 It arises from the anterior sacral foramen, deep to the parietal fascia that covers the pelvic surfaces of the muscles lining the pelvic cavity. The nerve to the levator ani may also be seen, arising from S3 and S4 with the nerve eirgentes. The deep narrow cavity often makes the surgeon excessively retract the rectum posteriorly and laterally; pelvic plexus injury can then easily occur.

Fig. 9.

On operative field, bifurcation of the superior hypogastric nerve was noted at the aortic bifurcation. The inferior hypogastric nerve descends along the pelvic side wall. The pelvic plexus forms after merging with the sacral parasympathetic nerve.

A sharp dissection around these areas may be necessary. Therefore, preservation of the sacral parasympathetic nerve does not seem to be feasible in patients with a narrow and deep pelvis.

Sometimes, urologists help colorectal surgeons to learn surgical anatomical knowledge regarding nerve-sparing surgery. Based on Walsh's report35 on nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy, the seminal vesicle can be used as a landmark intraoperatively to identify the pelvic plexus, which is imbedded in thick fascia and perforated by branches of inferior vesical artery and vein. The running neurovascular bundle is located at the extreme lateral part of the seminal vesicle, which is a continuation of the pelvic plexus at the lateral pelvic wall. He pointed out several anatomical regions where injury to nerves important for sexual function may occur during rectal surgery. Injury to the hypogastric nerves in the retroperitoneal space along the peritoneal reflection of the sigmoid mesentery may result in ejaculatory dysfunction. Excessive traction on the rectum with anterior displacement of the rectum secondary to mobilization posterior to the rectum may result in neuropraxia or avulsion of sacral roots 2, 3, and 4. These injuries could result in temporary or permanent bladder and/or erectile dysfunction.

A higher incidence of sexual and bladder dysfunction has been reported after APR than after LAR. During APR, injury to the cavernous nerves during perineal dissection may result in erectile dysfunction, as well. Division of the rectourethralis muscle and blunt dissection or excessive electrocauterization of the neurovascular bundle at the anterolateral part of the rectum may also contribute to sexual dysfunction.

PERINEUM DISSECTION DURING ABDOMINOPERINEAL RESECTION

Abdominoperineal resection can be considered to consist of total mesorectal excision during abdominal phase and sharp anatomical perineal dissection. The concept of TME is to perform precise anatomical pelvic dissection along the rectal proper fascia surrounding the mesorectum; the mesorectum disappears 1-2 cm above the levator ani muscle. In most cases, the rectal wall is attached lightly to the thin levator ani muscle; hence, the levator ani muscle can be seen only after the dissection finished. If the tumor were located in its vicinity, dissection around this area should be avoided. Concerning the practicality of operative techniques, abdominal phase techniques are the same as TME techniques. Sharp pelvic dissection must be carried out along the visceral fascia enveloping the mesorectum to the levator ani muscle with preservation of pelvic autonomic nerve. Perineal phase dissection is a key process in APR. During perineal dissection, an inadequate resection margin and blunt dissection along the nonanatomical plane encourage implantation of a malignant cell and local recurrence. Moreover, nonanatomical dissection can lead to serious complications, such as prostatic urethral injury, vaginal wall perforation, perineal sinus, and fistula. Massive bleeding from pelvic side wall major vessel injury might occur, especially in males with a narrow pelvis. In patients with a narrow, deep pelvic cavity, it is nearly impossible to reach the levator ani muscle, resulting in the performance of perineal dissection at excessively high levels. For colorectal surgeons with insufficient experience, it is difficult to dissect the rectum from the perineum to the seminal vesicle level. In the classic pattern, anterior and lateral dissection from the prostate or vagina occurs after completion of posterior dissection. The dissected proximal colon is delivered outward through the perineal wound and, with traction of the delivered portion of the colon, anterior dissection is performed. However, in patients with a narrow pelvis, such delivery of the proximal colon through the perineal wound can result in a fractured tumor and local recurrence due to limited operation field. Therefore, it is mandatory that the specimen be delivered in situ after posterior, anterior, and lateral dissection.15 During posterior dissection, the gluteus muscle must be observed and removal of ischiorectal fat tissue should be accomplished. In lateral dissection, the levator ani muscle must be divided near the bony insertion. During anterior dissection, the seminal vesicle and prostate gland must be exposed and the neurovascular bundle observed in the 10 o'clock and 2 o'clock directions.

The so-called sharp anatomical perineal dissection empowered by 3D concept based on pelvic MRI is important in preventing local recurrence. Interestingly, important anatomical structures can be seen by pelvic MRI. On a coronal view, the anal sphincter and levator ani muscle are clearly seen. Therefore, we can get information on whether the anal sphincter is involved by MRI and digital examination. If the cancer invaded the sphincter muscle preoperatively, APR should be performed without hesitation. On a MRI coronal view, the cancer is located close to the obturator muscle and a natural waist is formed between the ischiorectal fat and the mesorectum which terminates directly above the levator ani muscle. Shown in the figure of the vicinity of the imaginary dissection line, metastatic lymph nodes can be observed. Possible metastatic lymph nodes are present in the mesorectum and located only 1-2 mm away from the dissection plane in deep pelvis (Fig. 7B). Therefore, a metastatic lymph node can be injured readily; hence, tumor cell seeding could also occur readily. At the time of perineal dissection, metastatic lymph nodes are also located close to the planned dissection line. An inadequate dissection plane or shorter resection margin could facilitate tumor cell seeding or residual cancer cells, similar to an inappropriate total mesorectal excision.

Recently Marr et al.38 reported that in the linear dimension of transverse slices of tissue containing the tumor, the median, posterior, and lateral measurements were smaller in the APR than the AR. He observed that APR specimens with a histologically-positive CRM (Circumferential Resection Margin) had a smaller area of tissue outside the muscularis propria compared to CRM-negative APR specimens. Therefore, the incidence of CRM involvement in the APR groups was higher than for the AR group, which is main reason for higher local recurrence of APR.

Based on this data, during APR, a wider resection margin should be obtained based on the MR anatomical plane.

In the perineum, important landmarks are the superficial and deep perineal muscle in the perineal body anteriorly and the anococcygeal ligament posteriorly. A couple of vessels encountered during perineal dissection are branches from the internal pudendal artery and vein. The levator ani muscle must be cut at the level of bone insertion and should be done with a wide resection margin Practically, we can get information about the relationship between the tumor and the levator ani muscle and anal sphincter muscle on an axial and coronal view of pelvic MRI and can avoid dissection around the tumor level.

Recently published data showed acceptable functional and oncologic outcomes of intersphincteric resection for low rectal cancer, and recommended it as a valuable procedure for sphincter-saving rectal surgery.39 The same authors also stressed that preoperative MR evaluation for rectal cancer shows tumor invasion of the internal, external, or levator ani muscle. We must exclude patients who have external sphincter invasion, puborectalis, or levator ani muscle invasion.

Furthermore, Brown et al.40 reported that anatomically-dissected hemipelvis were compared by MR image to establish criteria for visualization of the structures relevant to low anterior resection of the rectum. They beautifully described not only depth of tumor invasion of the rectal wall, but also the mesorectal fascia and pelvic autonomic nerve. We can get much information of importance in the staging of the tumor, resectability, planning the extent of lymph node dissection, and selecting patients who need neoadjuvant chemoradiation therapy.

FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

A Tumor Specific Mesorectal Excision (TSME) workshop was held last October for the first time in Korea. Many young surgeons participated in discussion and observed live surgery of TSME of rectal cancer.41 Hopefully in the future, multicenter trials study will prove the oncologic benefits of TSME. In a national Norwegian audit involving 3,319 new patients, the technique of TME was compared with conventional surgery. The observed local recurrence rates for patients undergoing curative resection were 6% in the group treated by TME and 12% in the conventional surgery group, while the 4 year survival rates were 73% after TME and 60% after conventional surgery.42 Other Scandinavian countries had better oncologic outcomes after the TME workshop and education training system. Sharp pelvic dissection under direct vision based on anatomical knowledge has become essential in the field of rectal cancer surgery. Cadaveric dissection enables surgeons to perform sharp pelvic dissection based on the surgical anatomy of rectal cancer surgery.31

CONCLUSIONS

Sharp pelvic dissection and sharp perineal dissection based on an anatomical and 3D MR image-based concept is important for the curative resection of rectal cancer. Also, a safe operation and good quality of life after surgery can be provided to patients with rectal cancer. Sharp anatomical pelvic dissection is the key to producing good functional and oncologic outcomes. Macroscopic assessment of gross specimen after the tumor is resected is essential for colorectal surgeons because any kind of defect on the mesorectum or tumor close to the resection margin, narrow and shorter margin around the waist of APR specimen should be avoided.

Pre or post adjuvant modality approaches can achieve optimal goals for treatment. Functional consideration should be considered at the time of surgery planning.

Footnotes

This work was supported by a grant of the Korean Health 21 R&D Project, Ministry of Health&Welfare, Republic of Korea (0412-CR01-0704-0001).

References

- 1.NIH consensus conference. Adjuvant therapy for patients with colon and rectal cancer. JAMA. 1990;264:1444–1450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maurer CA, Z'Graggen K, Renzulli P, Schilling MK, Netzer P, Buchler MW. Total mesorectal excision preserves male genital function compared with conventional rectal cancer surgery. Br J Surg. 2001;88:1501–1505. doi: 10.1046/j.0007-1323.2001.01904.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heald RJ, Husband EM, Ryall RD. The mesorectum in rectal cancer surgery-the clue to pelvic recurrence? Br J Surg. 1982;69:613–616. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800691019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heald RJ, Ryall RD. Recurrence and survival after total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer. Lancet. 1986;1:1479–1482. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(86)91510-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.MacFarlane JK, Ryall RD, Heald RJ. Mesorectal excision for rectal cancer. Lancet. 1993;341:457–460. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)90207-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Enker WE, Thaler HT, Cranor ML, Polyak T. Total mesorectal excision in the operative treatment of carcinoma of the rectum. J Am Coll Surg. 1995;181:335–346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Enker WE, Merchant N, Cohen AM, Lanouette NM, Swallow C, Guillem J, et al. Safety and efficacy of low anterior resection for rectal cancer: 681 consecutive cases from a specialty service. Ann Surg. 1999;230:544–554. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199910000-00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sugihara K, Moriya Y, Akasu T, Fujita S. Pelvic autonomic nerve preservation for patients with rectal carcinoma. Oncologic and functional outcome. Cancer. 1996;78:1871–1880. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim NK, Aahn TW, Park JK, Lee KY, Lee WH, Sohn SK, et al. Assessment of sexual and voiding function after total mesorectal excision with pelvic autonomic nerve preservation in males with rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:1178–1185. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6388-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Quirke P, Durdey P, Dixon MF, Williams NS. Local recurrence of rectal adenocarcinoma due to inadequate surgical resection. Histopathological study of lateral tumor spread and surgical excision. Lancet. 1986;2:996–999. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(86)92612-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adam IJ, Mohamdee MO, Martin IG, Scott N, Finan PJ, Johnston D, et al. Role of circumferential margin involvement in the local recurrence of rectal cancer. Lancet. 1994;344:707–711. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)92206-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takahashi T, Ueno M, Azekura K, Ohta H. Lateral node dissection and total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:S59–S68. doi: 10.1007/BF02237228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fujita S, Yamamoto S, Akasu T, Moriya Y. Lateral pelvic lymph node dissection for advanced lower rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2003;90:1580–1585. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bisset IP, Chau KY, Hill GL. Extrafascial excision of the rectum: surgical anatomy of the fascia propria. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:903–910. doi: 10.1007/BF02237349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diop M, Parratte B, Tatu L, Vuillier F, Brunelle S, Monnier G. "Mesorectum": the surgical value of an anatomical approach. Surg Radiol Anat. 2003;25:290–304. doi: 10.1007/s00276-003-0148-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim NK. Anatomic basis of sharp pelvic dissection for total mesorectal excision with pelvic autonomic nerve preservation for rectal cancer. J Korean Soc Coloproctol. 2004;20:424–433. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim NK. Sharp pelvic dissection for abdominoperineal resection for distal rectal cancer based on anatomical and MRI knowledge. J Korean Soc Coloproctol. 2005;21:258–267. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crapp AR, Cuthbertson AM. Willaim Waldeyer and the rectosacral fascia. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1974;138:252–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tobin CE, Benjamin JA. Anatomical and surgical restudy of Denonvilliers' fascia. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1945;80:373–388. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Milley PS, Nichols DH. A correlative investigation of the human rectovaginal septum. Anat Rec. 1969;163:443–451. doi: 10.1002/ar.1091630307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heald RJ, Moran BJ, Brown G, Daniels IR. Optimal total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer is by dissection in front of Denonvilliers' fascia. Br J Surg. 2004;91:121–123. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mundy AR. An anatomical explanation for bladder dysfunction following rectal and uterine surgery. Br J Urol. 1982;54:501–504. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1982.tb13575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoer J, Roegels A, Prescher A, Klosterhalfen B, Tons C, Schumpelick V. Preserving autonomic nerves in rectal surgery. Results of surgical preparation on human cadavers with fixed pelvic sections. Chirurg. 2000;71:1222–1229. doi: 10.1007/s001040051206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sato K, Sato T. The vascular and neuronal composition of the lateral ligament of the rectum and the rectosacral fascia. Surg Radiol Anat. 1991;13:17–22. doi: 10.1007/BF01623135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamakoshi H, Ike H, Oki S, Hara M, Shimada H. An assessment of the anatomical relationship between the pelvic plexus and the rectal wall to determine the indications for its preservation in surgery for rectal cancer. Surg Today. 1997;27:1005–1009. doi: 10.1007/BF02385779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Widmer O. Rectal arteries in man; entrance, caliber, distribution, anastomosis and supply area. Z Anat Entwicklungs-gesc. 1955;118:398–416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.DiDio LJ, Diaz-Franco C, Schemainda R, Bezerra A. Morphology of the middle rectal arteries: A study of 30 cadaveric dissections. Surg Radiol Anat. 1986;8:229–236. doi: 10.1007/BF02425072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nano M, Dal Corso HM, Lanfranco G, Ferronato M, Hornung JP. Contribution to the surgical anatomy of the ligaments of the rectum. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:1592–1598. doi: 10.1007/BF02236746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jones OM, Smeulders N, Wiseman O, Miller R. Lateral ligaments of the rectum: an anatomical study. Br J Surg. 1999;86:487–489. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1999.01080.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee JF, Maurer VM, Block GE. Anatomic relations of pelvic autonomic nerves to pelvic operations. Arch Surg. 1973;107:324–328. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1973.01350200184038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kirkham AP, Mundy AR, Heald RJ, Scholefield JH. Cadaveric dissection for the rectal surgeon. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2001;83:89–95. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Walsh PC, Donker PJ. Impotence following radical prostatectomy: insight into etiology and prevention. J Urol. 1982;128:492–497. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)53012-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Havenga K, Maas CP, DeRuiter MC, Welvaart K, Trimbos JB. Avoiding long-term disturbance to bladder and and sexual function in pelvic surgery, particularly with rectal cancer. Semin Surg Oncol. 2000;18:235–243. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2388(200004/05)18:3<235::aid-ssu7>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Havenga K, DeRuiter MC, Enker WE, Welvaart K. Anatomical basis of autonomic nerve-preserving total mesorectal excision for rectal camcer. Br J Surg. 1996;83:384–388. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800830329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Walsh PC, Schlegel PN. Radical pelvic surgery with preservation of sexual function. Ann Surg. 1988;208:391–400. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198810000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hollabaugh RS, Jr, Steiner MS, Sellers KD, Samm BJ, Dmochowski RR. Neuroanatomy of the pelvis: implications for colonic and rectal resection. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:1390–1397. doi: 10.1007/BF02236635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Church JM, Raudkivi PJ, Hill GL. The surgical anatomy of the rectum - a review with particular relevance to the hazards of rectal mobilization. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1987;2:158–166. doi: 10.1007/BF01648000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marr R, Birbeck K, Garvican J, Macklin CP, Tiffin NJ, Parsons WJ, et al. The modern abdominoperineal excision: the next challenge after total mesorectal excision. Ann Surg. 2005;242:74–82. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000167926.60908.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schiessel R, Novi G, Holzer B, Rosen HR, Renner K, Hoebling N, et al. Technique and long-term results of intersphincteric resection for low rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:1858–1867. doi: 10.1007/s10350-005-0134-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brown G, Kirkham A, Williams GT, Bourne M, Radcliffe AG, Sayman J, et al. High-resolution MRI of the anatomy important in total mesorectal excision of the rectum. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;182:431–439. doi: 10.2214/ajr.182.2.1820431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim NK, editor. Tumor specific mesorectal excision for rectal cancer workshop; Seoul. MEDrang Inc.: Clinical research center for solid tumor sponsored by the Korean Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea; 2005. Contract No. 0412-CR01-0704-0001. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wibe A, Moller B, Norstein J, Carlsen E, Wiig JN, Heald RJ, et al. A national strategic change in treatment policy for rectal cancer-implementation of total mesorectal excision as routine treatment in Norway. A national audit. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:857–866. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6317-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]