Abstract

Chibby (Cby) is an evolutionarily conserved antagonist of β-catenin, a central player of the canonical Wnt signaling pathway, which acts as a transcriptional coactivator. Cby physically interacts with the C-terminal activation domain of β-catenin and blocks its transcriptional activation potential through competition with DNA-binding Tcf/Lef transcription factors. Our recent study revealed a second mechanism for Cby-mediated β-catenin inhibition in which Cby cooperates with 14-3-3 adaptor proteins to facilitate nuclear export of β-catenin, following phosphorylation of Cby by Akt kinase. Therefore, our findings unravel a novel molecular mechanism regulating the dynamic nucleo-cytoplamic trafficking of β-catenin and provide new insights into the cross-talk between the Wnt and Akt signaling pathways. Here, we review recent literature concerning Cby function and discuss our current understanding of the relationship between Wnt and Akt signaling.

Keywords: Chibby, 14-3-3, β-catenin, Wnt, Akt, signaling, nuclear export, protein trafficking

Overview of the Canonical Wnt/β-Catenin Pathway

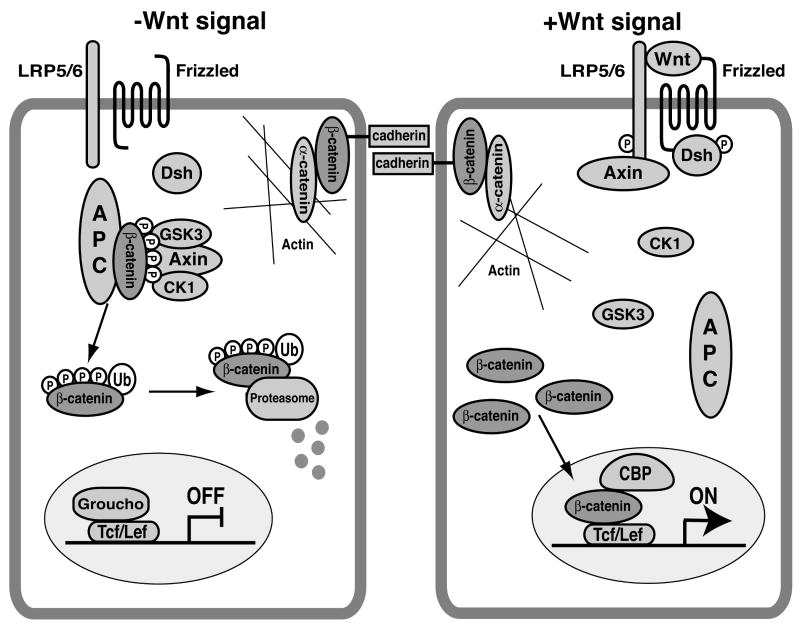

The Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway plays diverse roles in embryonic development, stem cell self-renewal and adult homeostasis.1-3 In recent years, perturbations in this signaling cascade have been implicated in the pathogenesis of a range of human diseases, especially cancer.4, 5 Remarkably, chronic activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling is found in a variety of human malignancies including melanoma, colorectal and hepatocellular carcinomas.2, 6 Accordingly, the Wnt/β-catenin pathway has gained recognition as an attractive molecular target for cancer therapeutics as well as Wnt-related disorders.4, 7 In this signaling pathway, β-catenin is a key component, functioning as a transcriptional coactivator.8 In the absence of an extracellular Wnt ligand (Fig. 1, left panel), cytoplasmic β-catenin becomes phosphorylated by casein kinase 1 (CK1) and glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3) in the so-called “destruction complex” containing the tumor suppressors Axin and Adenomatous polyposis coli (APC), and is targeted for ubiquitin-mediated proteasomal degradation.9 Binding of Wnt to the seven transmembrane Frizzled (Fz) receptors and the low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein (LRP) co-receptors, LRP5 and LRP6, triggers recruitment of Axin to the plasma membrane, resulting in inhibition of β-catenin phosphorylation and degradation (Fig. 1, right panel).10 As a result, β-catenin accumulates in the cytoplasm and then translocates into the nucleus where it forms a complex with the T-cell factor/lymphoid enhancer factor (Tcf/Lef) family of transcription factors, leading to activation of target genes.11, 12 Thus, nuclear β-catenin is the hallmark of activated Wnt signaling and frequently observed in tumor cells.2, 6 β-Catenin also functions in cell adhesion by binding to type I cadherins to mediate actin filament assembly via α-catenin at the plasma membrane.8

Figure 1.

Simplified overview of the canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. (left panel) In the absence of a Wnt signal, β-catenin is sequestered in the destruction complex containing the scaffold proteins APC and Axin, and sequentially phosphorylated by the kinases CK1 and GSK3. This results in degradation of β-catenin via the uiquitin-proteasome pathway. In the nucleus, Tcf/Lef target genes are repressed through recruitment of transcriptional co-repressors including Groucho. (right panel) Upon Wnt signaling, Frz-Dsh complex formation and the sequential phosphorylation of LRP5/6 by GSK3 and CK1 promote translocation of Axin to the plasma membrane, leading to inactivation of the destruction complex. Stabilized β-catenin then enters the nucleus and forms a complex with Tcf/Lef factors to stimulate expression of Wnt target genes by recruiting various co-activators such as CBP. β-Catenin is also a key component of cell-cell adhesion, linking cadherins to the actin cytoskeleton.

Cby Is an Evolutionarily Conserved β-Catenin Antagonist

To explore the molecular basis for controlling β-catenin signaling activity, we performed a yeast Ras recruitment screen using the C-terminal transactivation domain of β-catenin as bait and pulled out Chibby (Cby).13 Cby is a 15-kDa protein that is highly conserved throughout evolution from fly to human. It harbors putative nuclear localization signals (NLSs) and a conserved α-helical coiled-coil motif in the C-terminal region. Our recent crystal structural analyses of full-length β-catenin indicate that Cby binds to the Helix C located at the C-terminal end of the central Armadillo repeat region of β-catenin.14 By doing so, Cby competes with Tcf/Lef transcription factors for binding to β-catenin, leading to repression of Wnt target genes (Fig. 2). Consistent with this notion, RNAi knockdown of Cby in Drosophila melanogaster embryos results in hyperactivation of this signaling pathway, highlighting the biological importance of Cby function.13, 15 In cell culture systems, Cby facilitates adipocyte and cardiomyocyte differentiation of pluripotent stem cells through inhibition of β-catenin signaling.16, 17 As the oncogenic role of aberrantly activated β-catenin is well documented, Cby may act as a tumor suppressor. In fact, it has been reported that Cby expression is down-regulated in certain tumors such as colon carcinoma cell lines18 and pediatric ependymomas.19

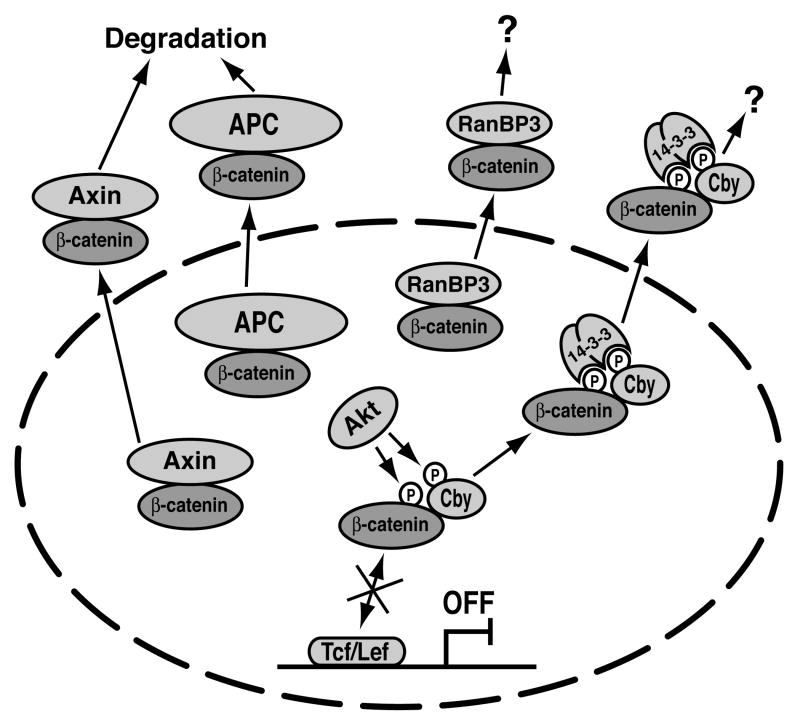

Figure 2.

Inhibition of β-catenin signaling by Cby and other nuclear export pathways. In the nucleus, Cby interacts with β-catenin and competes with Tcf/Lef transcription factors, thereby blocking expression of target genes. In addition, phosphorylation of Cby and β-catenin by Akt facilitates 14-3-3 binding, resulting in nuclear export of β-catenin to the cytoplasm. APC, Axin and RanBP3 have been shown to promote nuclear export of β-catenin. See text for details.

Second Mode of β-Catenin Inhibition by Cby via Cooperation with 14-3-3

To extend our knowledge on the cellular and molecular function of Cby, we set out to identify Cby-binding proteins using an affinity purification/mass spectrometry approach, and isolated two isoforms of the 14-3-3 adaptor protein family, ζ and ε.20 14-3-3 proteins constitute a family of highly conserved dimeric proteins, comprised of 7 isoforms in mammals (β, γ, ε, σ, ζ, τ and η).21, 22 The family members are widely expressed and often control activity and/or subcellular localization of their target proteins. 14-3-3 binding typically depends on phosphorylation of serine (S)/threonine (T) residues in their substrates. We showed that 14-3-3 proteins specifically recognize S20 within the N-terminal 14-3-3-binding motif of Cby upon phosphorylation by Akt kinase.20 A single-amino-acid substitution of alanine (A) for S20 almost completely abolishes the interaction of Cby with 14-3-3. Notably, direct docking of 14-3-3 results in sequestration of Cby into the cytoplasm. More importantly, Cby and 14-3-3 form a stable trimolecular complex with β-catenin and translocate β-catenin into the cytoplasmic compartment, thereby suppressing β-catenin signaling activity. Inhibition of Wnt/β-catenin signaling by Cby, therefore, involves at least two distinct molecular mechanisms (Fig. 2), i.e. competing with Tcf/Lef factors for binding to β-catenin in the nucleus, and facilitating nuclear export of β-catenin via interaction with 14-3-3. Both mechanisms appear to be necessary for Cby to achieve full repression of β-catenin transcriptional activity. In support of this model, 14-3-3-binding-defective Cby mutants exhibit significantly reduced ability to repress β-catenin-mediated activation of the Tcf/Lef luciferase reporter TOPFLASH even though these Cby mutants accumulate in the nucleus. However, it is also conceivable that one mechanism predominates over the other, depending on the cellular context. Intriguingly, under the experimental conditions we tested, 14-3-3 proteins preferentially collaborate with Cby to relocate β-catenin into the cytoplasm rather than sequestering Cby alone. Nevertheless, 14-3-3 might, under certain circumstances, sequester Cby away from β-catenin, now allowing β-catenin to stimulate target gene expression.

A previous proteomic study identified 14-3-3ζ as a β-catenin interactor.23 In another report,24 it was shown that β-catenin is phosphorylated at S552 by Akt downstream of epidermal growth factor (EGF) signaling. This phosphorylation promotes the association of β-catenin with 14-3-3ζ. In contrast to our model, ectopic expression of 14-3-3ζ results in a moderate increase in TOPFLASH activation by β-catenin.23, 24 This apparent discrepancy might be explained by the fact that 14-3-3 proteins have been shown to interact with over 200 proteins including transcription factors and various signaling molecules,22, 25 and hence its overexpression can elicit pleiotropic effects. Another complicating factor is that 14-3-3ζ enhances whereas 14-3-3η and ε isoforms repress β-catenin-dependent gene activation although all three 14-3-3 isoforms bind to Cby and sequester it into the cytoplasm,20 suggesting isoform-specific effects of 14-3-3 proteins on Wnt signaling. At present, the exact mechanisms underlying potentiation of β-catenin signaling by 14-3-3ζ is unclear. However, it is worth pointing out that, consistent with our results, ectopic expression of 14-3-3ζ was found to cause the cytoplasmic enrichment of β-catenin,23 presumably by interacting with endogenous Cby. In any case, our findings indicate that the Cby-14-3-3 interaction significantly contributes to their stable complex formation with β-catenin. Moreover, 14-3-3 itself is not sufficient to sequester β-catenin into the cytoplasm as Cby mutants incapable of binding to 14-3-3 retain β-catenin in the nucleus even in the presence of excess 14-3-3.20 We therefore propose that phosphorylation of β-catenin and Cby by Akt provokes 14-3-3 binding to form a stable ternary complex, followed by β-catenin nuclear export and termination of its signaling (Fig. 2).

Nuclear targeting of β-catenin is a prerequisite for activation of Wnt target genes. Thus, nuclear import/export of β-catenin represents a crucial step in regulating signaling competent β-catenin levels and serves as an attractive target for pharmacological interventions in cancer and other diseases associated with altered Wnt signaling. To date, several distinct β-catenin nuclear export pathways have been reported. For example, APC and Axin, besides their function in the destruction complex, have been shown to shuttle between the nucleus and the cytoplasm, and facilitate nuclear export of β-catenin by the classical chromosome region maintenance-1 (CRM-1)-dependent pathway (Fig. 2).26-29 On the other hand, the RanBP3 export factor enhances nuclear export of active β-catenin in a CRM-1-independent manner.30 The APC- and Axin-directed nuclear export pathways may be coupled with proteasomal degradation of β-catenin. However, the outcomes of the Cby and RanBP3-dependent export are currently unknown. In addition, how these nuclear export routes operate coordinately and differentially to fine-tune nuclear β-catenin levels remains largely elusive.

Other Cby-Binding Partners

Besides β-catenin and 14-3-3, Cby has been shown to interact with thyroid cancer-1 (TC-1)31 and polycystin-2 (PC-2).32 TC-1 was originally identified as a gene whose expression was elevated in thyroid cancers.33 More recently, TC-1 was shown to bind to Cby and stimulate β-catenin-dependent transcriptional activation by displacing Cby from β-catenin.31 However, its precise physiological functions are not yet completely understood. PC-2 is another known binding partner of Cby.32 The PDK-2 gene, encoding PC-2, is mutated in patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease.34, 35 Hidaka et al. reported that Cby associates with PC-2 and controls its subcellular distribution.32 Upon coexpression in mammalian cultured cells, Cby and PC-2 proteins redistribute and colocalize to the trans-Golgi network although Cby primarily localizes to the cytoplasm on its own. It is, therefore, tempting to speculate that Cby, in cooperation with 14-3-3 proteins, may regulate the intracellular localization of PC-2 and potentially other binding proteins.

Cross-Talk between the Akt and Wnt/β-Catenin Pathways

Akt [also known as protein kinase B (PKB)] belongs to the AGC subfamily of S/T kinases, and is a pivotal effector of the phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K) signaling, which is activated by a diverse array of extracellular stimuli and known to promote cell growth, survival and tumor formation.36, 37 Prior reports suggest that Akt positively regulates β-catenin signaling, most likely acting at the level of the β-catenin destruction complex although its precise mechanism of action remains largely debatable.23, 24, 38 Several lines of evidence indicate that, like insulin signaling, Akt-mediated phosphorylation inhibits GSK3 activity, resulting in stabilization of β-catenin.39, 40 In agreement with this, GSK3 inactivation and the resultant nuclear accumulation of β-catenin were observed in intestinal tumors of mice carrying conditional deletion of the tumor suppressor PTEN,41 which acts as a negative regulator of the PI3K/Akt pathway. It is, therefore, somewhat puzzling to find that Akt phosphorylation of Cby facilitates its interaction with 14-3-3 and triggers the cytoplasmic sequestration of β-catenin, thereby attenuating β-catenin signaling. However, it is plausible that membrane/cytoplasmic activated Akt favorably phosphorylates and thus inactivates GSK3, while nuclear Akt phosphorylates β-catenin and Cby, which in turn facilitates 14-3-3 binding, resulting in nuclear exclusion of the ternary complex. In support of this idea, we found that nuclear-targeted Akt inhibits whereas membrane-tethered Akt stimulates β-catenin-mediated transcriptional activation.20 Once activated at the plasma membrane in response to a range of stimuli, Akt translocates into the nucleus where it phosphorylates and modulates the activity of nuclear factors including Forkhead transcription factors and p300/CBP coactivators.42-45 However, there is limited information available about the physiological functions of nuclear Akt. Our work clearly demonstrates that the subcellular compartmentalization of Akt differentially influences β-catenin signaling. This is reminiscent of GSK3 as it both positively and negatively affects Wnt/β-catenin signaling depending on its intracellular location.46 It is also likely that phosphorylation of Cby at serine 20 is catalyzed by additional kinases since 14-3-3-binding consensus motifs have been shown to be phosphorylated by various protein kinases.21, 22

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge support by a Junior Faculty Award from the American Diabetes Association (107JF42) to Feng-Qian Li, and a National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) grant DK073191 to Ken-Ichi Takemaru.

References

- 1.Pinto D, Clevers H. Wnt control of stem cells and differentiation in the intestinal epithelium. Exp Cell Res. 2005;306:357–63. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klaus A, Birchmeier W. Wnt signalling and its impact on development and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:387–98. doi: 10.1038/nrc2389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wodarz A, Nusse R. Mechanisms of Wnt signaling in development. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1998;14:59–88. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.14.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moon RT, Kohn AD, De Ferrari GV, Kaykas A. WNT and beta-catenin signalling: diseases and therapies. Nat Rev Genet. 2004;5:691–701. doi: 10.1038/nrg1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clevers H. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in development and disease. Cell. 2006;127:469–80. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Polakis P. Wnt signaling and cancer. Genes Dev. 2000;14:1837–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takemaru K, Ohmitsu M, Li FQ. An oncogenic hub: beta-catenin as a molecular target for cancer therapeutics. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2008;186:261–84. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-72843-6_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takemaru KI. Catenin, beta. UCSD-Nature Molecule Pages. 2006 doi: 10.1038/mp.a000506.01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kimelman D, Xu W. beta-catenin destruction complex: insights and questions from a structural perspective. Oncogene. 2006;25:7482–91. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang H, He X. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling: new (and old) players and new insights. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2008;20:119–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2008.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Willert K, Jones KA. Wnt signaling: is the party in the nucleus? Genes Dev. 2006;20:1394–404. doi: 10.1101/gad.1424006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stadeli R, Hoffmans R, Basler K. Transcription under the control of nuclear Arm/beta-catenin. Curr Biol. 2006;16:R378–85. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takemaru K, Yamaguchi S, Lee YS, Zhang Y, Carthew RW, Moon RT. Chibby, a nuclear beta-catenin-associated antagonist of the Wnt/Wingless pathway. Nature. 2003;422:905–9. doi: 10.1038/nature01570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xing Y, Takemaru K, Liu J, Berndt JD, Zheng JJ, Moon RT, et al. Crystal structure of a full-length beta-catenin. Structure. 2008;16:478–87. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2007.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tolwinski NS, Wieschaus E. A nuclear function for armadillo/beta-catenin. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:E95. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singh AM, Li FQ, Hamazaki T, Kasahara H, Takemaru K, Terada N. Chibby, an antagonist of the Wnt/beta-catenin pathway, facilitates cardiomyocyte differentiation of murine embryonic stem cells. Circulation. 2007;115:617–26. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.642298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li FQ, Singh AM, Mofunanya A, Love D, Terada N, Moon RT, et al. Chibby promotes adipocyte differentiation through inhibition of beta-catenin signaling. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:4347–54. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01640-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schuierer MM, Graf E, Takemaru K, Dietmaier W, Bosserhoff AK. Reduced expression of beta-catenin inhibitor Chibby in colon carcinoma cell lines. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:1529–35. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i10.1529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karakoula K, Suarez-Merino B, Ward S, Phipps KP, Harkness W, Hayward R, et al. Real-time quantitative PCR analysis of pediatric ependymomas identifies novel candidate genes including TPR at 1q25 and CHIBBY at 22q12-q13. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2008;47:1005–22. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li FQ, Mofunanya A, Harris K, Takemaru K. Chibby cooperates with 14-3-3 to regulate beta-catenin subcellular distribution and signaling activity. J Cell Biol. 2008;181:1141–54. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200709091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aitken A. 14-3-3 proteins: a historic overview. Semin Cancer Biol. 2006;16:162–72. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dougherty MK, Morrison DK. Unlocking the code of 14-3-3. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:1875–84. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tian Q, Feetham MC, Tao WA, He XC, Li L, Aebersold R, et al. Proteomic analysis identifies that 14-3-3zeta interacts with beta-catenin and facilitates its activation by Akt. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:15370–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406499101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fang D, Hawke D, Zheng Y, Xia Y, Meisenhelder J, Nika H, et al. Phosphorylation of beta -catenin by AKT promotes beta -catenin transcriptional activity. J Biol Chem. 2007 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611871200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pozuelo Rubio M, Geraghty KM, Wong BH, Wood NT, Campbell DG, Morrice N, et al. 14-3-3-affinity purification of over 200 human phosphoproteins reveals new links to regulation of cellular metabolism, proliferation and trafficking. Biochem J. 2004;379:395–408. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rosin-Arbesfeld R, Townsley F, Bienz M. The APC tumour suppressor has a nuclear export function. Nature. 2000;406:1009–12. doi: 10.1038/35023016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Henderson BR. Nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling of APC regulates beta-catenin subcellular localization and turnover. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:653–60. doi: 10.1038/35023605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cong F, Varmus H. Nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling of Axin regulates subcellular localization of beta-catenin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:2882–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307344101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wiechens N, Heinle K, Englmeier L, Schohl A, Fagotto F. Nucleo-cytoplasmic shuttling of Axin, a negative regulator of the Wnt-beta-catenin Pathway. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:5263–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307253200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hendriksen J, Fagotto F, van der Velde H, van Schie M, Noordermeer J, Fornerod M. RanBP3 enhances nuclear export of active (beta)-catenin independently of CRM1. J Cell Biol. 2005;171:785–97. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200502141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jung Y, Bang S, Choi K, Kim E, Kim Y, Kim J, et al. TC1 (C8orf4) enhances the Wnt/beta-catenin pathway by relieving antagonistic activity of Chibby. Cancer Res. 2006;66:723–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hidaka S, Konecke V, Osten L, Witzgall R. PIGEA-14, a novel coiled-coil protein affecting the intracellular distribution of polycystin-2. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:35009–16. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M314206200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chua EL, Young L, Wu WM, Turtle JR, Dong Q. Cloning of TC-1 (C8orf4), a novel gene found to be overexpressed in thyroid cancer. Genomics. 2000;69:342–7. doi: 10.1006/geno.2000.6348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilson PD. Polycystic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:151–64. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra022161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mochizuki T, Wu G, Hayashi T, Xenophontos SL, Veldhuisen B, Saris JJ, et al. PKD2, a gene for polycystic kidney disease that encodes an integral membrane protein. Science. 1996;272:1339–42. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5266.1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hennessy BT, Smith DL, Ram PT, Lu Y, Mills GB. Exploiting the PI3K/AKT pathway for cancer drug discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2005;4:988–1004. doi: 10.1038/nrd1902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Datta SR, Brunet A, Greenberg ME. Cellular survival: a play in three Akts. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2905–27. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.22.2905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brazil DP, Park J, Hemmings BA. PKB binding proteins. Getting in on the Akt Cell. 2002;111:293–303. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01083-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sharma M, Chuang WW, Sun Z. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt stimulates androgen pathway through GSK3beta inhibition and nuclear beta-catenin accumulation. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:30935–41. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201919200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ishibe S, Haydu JE, Togawa A, Marlier A, Cantley LG. Cell confluence regulates hepatocyte growth factor-stimulated cell morphogenesis in a beta-catenin-dependent manner. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:9232–43. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01312-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.He XC, Yin T, Grindley JC, Tian Q, Sato T, Tao WA, et al. PTEN-deficient intestinal stem cells initiate intestinal polyposis. Nat Genet. 2007;39:189–98. doi: 10.1038/ng1928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huang WC, Chen CC. Akt phosphorylation of p300 at Ser-1834 is essential for its histone acetyltransferase and transcriptional activity. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:6592–602. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.15.6592-6602.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Andjelkovic M, Alessi DR, Meier R, Fernandez A, Lamb NJ, Frech M, et al. Role of translocation in the activation and function of protein kinase B. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:31515–24. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.50.31515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Borgatti P, Martelli AM, Tabellini G, Bellacosa A, Capitani S, Neri LM. Threonine 308 phosphorylated form of Akt translocates to the nucleus of PC12 cells under nerve growth factor stimulation and associates with the nuclear matrix protein nucleolin. J Cell Physiol. 2003;196:79–88. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brunet A, Bonni A, Zigmond MJ, Lin MZ, Juo P, Hu LS, et al. Akt promotes cell survival by phosphorylating and inhibiting a Forkhead transcription factor. Cell. 1999;96:857–68. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80595-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zeng X, Tamai K, Doble B, Li S, Huang H, Habas R, et al. A dual-kinase mechanism for Wnt co-receptor phosphorylation and activation. Nature. 2005;438:873–7. doi: 10.1038/nature04185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]