Abstract

Nickel superoxide dismutase (Ni-SOD) catalyzes the disproportionation of superoxide to molecular oxygen and hydrogen peroxide, but the overall reaction mechanism has yet to be determined. Peptide-based models of the 2N:2S nickel coordination sphere of Ni-SOD have provided some insight into the mechanism of this enzyme. Here we show that the coordination sphere of Ni-SOD can be mimicked using the tripeptide asparagine-cysteine-cysteine (NCC). NCC binds nickel with extremely high affinity at physiological pH with 2N:2S geometry, as demonstrated by electronic absorption and circular dichroism (CD) data. Like Ni-SOD, Ni-NCC has mixed amine/amide ligation that favors metal-based oxidation over ligand-based oxidation. Electronic absorption, CD, and magnetic CD data (MCD) collected for Ni-NCC are consistent with a diamagnetic Ni(II) center bound in square planar geometry. Ni-NCC is quasi-reversibly oxidized with a midpoint potential of 0.72(2) V (versus Ag/AgCl) and breaks down superoxide in an enzyme-based assay, supporting its potential use as a model for Ni-SOD chemistry.

The radical species superoxide (O2•−) and its reactive downstream products are known to cause oxidative damage to biological molecules, and the presence of superoxide in the body has been linked to many different diseases.1 Superoxide dismutases (SODs) are oxidoreductases that catalyze the disproportionation of superoxide to hydrogen peroxide and molecular oxygen, therefore helping to protect biological systems from oxidative damage. These enzymes, classified by their metal center, include Cu/Zn-SODs, Fe- and Mn-SODs, and Ni-SODs.2

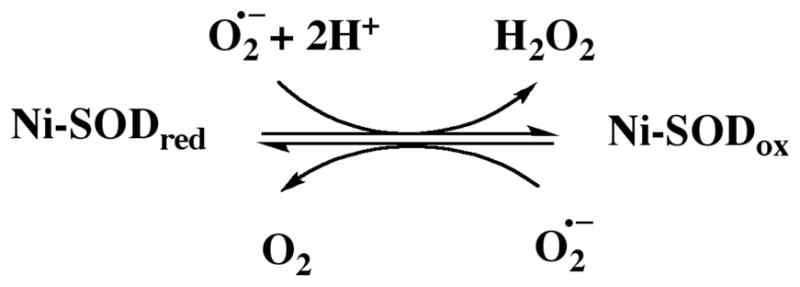

Ni-SOD is the most recently discovered form of the enzyme.3,4 Its active site contains a mononuclear nickel center5 coordinated in square planar geometry at the N-terminus of the enzyme via two cysteine sulfurs (Cys-2 and Cys-6), an amine nitrogen from the N-terminus, and a deprotonated, anionic amide nitrogen from the peptide backbone (Cys-2).6,7 Ni-SOD reacts with superoxide in a two-step reaction, involving oxidized and reduced forms of the enzyme (Scheme 1).3, 6–8

Scheme 1.

Reaction catalyzed by Ni-SOD.

As part of the redox reaction, the geometry of the bound nickel switches from square planar Ni(II) to square pyramidal Ni(III). An additional ligand, an axial nitrogen donor, coordinates Ni(III) in the resting state,3 and the X-ray crystal structure revealed this species to be the imidazole nitrogen of His-1. Upon reduction of the enzyme, the histidine imidazole rotates away from the active site, leaving Ni(II) coordinated in 2N:2S, square planar geometry.6, 7, 9

While much has been learned about the structure of the enzyme, only recently have studies begun to reveal more about the influence of the secondary coordination sphere.10,11 While recent studies support an inner sphere mechanism,12,13 the catalytic mechanism is not yet fully elucidated. In order to further explore these issues, it has been of interest to develop model systems that mimic the activity of this enzyme. Within Ni-SOD, the metal is coordinated by ligands found within the first six residues of the N-terminus.6,7 Synthetic models with square planar 2N:2S geometries have appropriate redox potentials to act as SOD mimics, yet these do not exhibit SOD activity.14–16 Peptide models based on the terminal sequence of the enzyme, however, have been shown to mimic SOD activity.12, 13, 17–19 Here we present a novel tripeptide mimic, asparagine-cysteine-cysteine (NCC), that exhibits both quasi-reversible Ni(II)/Ni(III) transitions and SOD activity. NCC is unique because it is not derived from the sequence of the parent enzyme. Because of its small size, this tripeptide is likely to have better stability and lower cost of production than larger peptide alternatives. Importantly, using an alternative simple model also has the potential to shed insight into the minimal geometric/electronic features necessary for SOD activity using Ni.

NCC binds nickel, apparently with extremely high affinity at physiological pH, and this system is thought to be a potential mimic of Ni-SOD based on similarities in coordination. To show the extent of incorporation of metal into the complex and assess changes in protonation of the free versus bound peptide, electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) operating in negative ion mode was used (Supporting Information). The data show full incorporation of the metal in a 1:1 ratio and suggest that no irreversible modifications to the peptide occur upon incorporation or release of the metal via acidification. These data further indicate a tetra-deprotonated species binds the metal ion (Ni-NCC = 391.98).

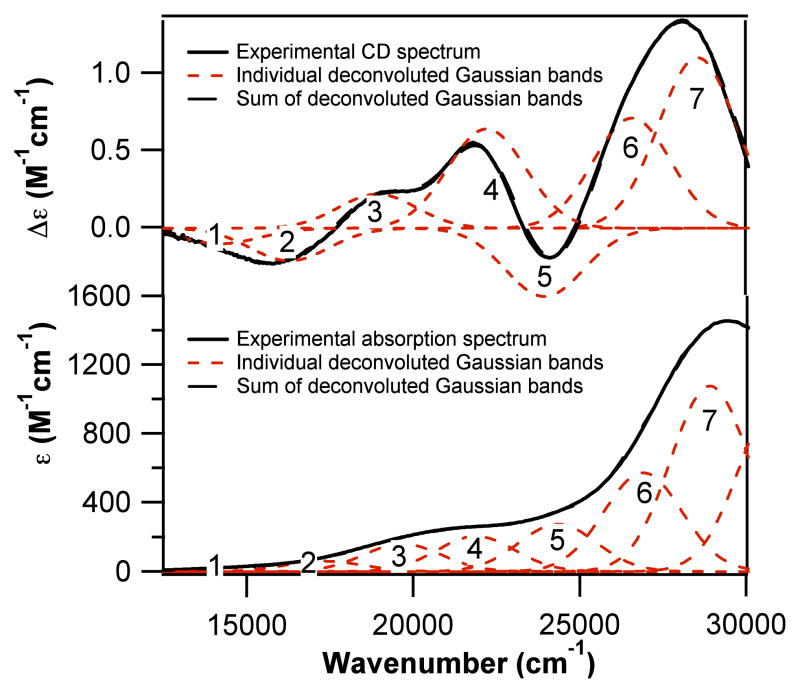

To probe the Ni(II) geometry in more detail, electronic absorption, circular dichroism (CD), and variable-temperature magnetic CD (MCD) data were collected for Ni-NCC. Absorption spectra collected over a broad range of concentrations of the complex resulted in an increase in band intensity, indicating that there is one primary species present in solution. An iterative deconvolution of the absorption and CD spectra reveal seven electronic transitions between 14 000 and 29 000 cm−1 (Figure 1 and Table 1; Supporting Information).

Figure 1.

Deconvoluted CD (top) and absorption (bottom) spectra of 1.5 mM Ni-NCC in 50 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4. Spectra were deconvoluted with Igor Pro (Wavemetrics).

Table 1.

Comparison of Ni-NCC and Ni-SOD CD transition energies and assignments. (Ni-SOD values were measured by Fiedler et al.21)

| Transition Assignment | Ni-NCC (cm−1) | Ni-SOD (cm−1) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | NiII d-d | 14 200 | 17 110 |

| 2 | NiII d-d | 16 270 | 18 430 |

| 3 | NiII d-d | 18 900 | 20 500 |

| 4 | NiII d-d | 22 170 | 22 240 |

| 5 | S− - NiII CT | 23 900 | 24 970 |

| 6 | S− - NiII CT | 26 520 | 27 650 |

| 7 | S− - NiII CT | 28 475 | 29 220 |

With the exception of band 1, the energies of these transitions are within ~1000 to 2000 cm−1 of those reported for Ni-SOD (Table 1), which is indicative of structural similarities between the Ni(II) centers in these two systems. Bands 1 – 4 of Ni-NCC, which are relatively intense in the CD spectrum but carry only moderate absorption intensities, are assigned as the four d-d transitions expected for a square planar Ni(II) center. By analogy to Ni-SOD, we assign the higher-energy bands 5 – 7 as thiolate-to-nickel(II) charge transfer (CT) transitions. Further support for the presence of a square planar Ni(II) center in Ni-NCC comes from the temperature independence of MCD signals observed for Ni-NCC over the temperature range 2 – 15 K (Supporting Information). This behavior is indicative of a diamagnetic (S = 0) species, which is best rationalized in terms of a square planar Ni(II) center.20

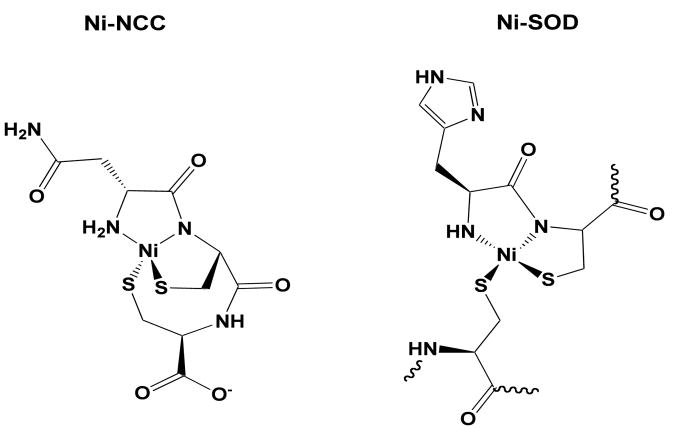

Based on the data presented above, nickel is coordinated in a square planar 2N:2S geometry. In Ni-SOD, the thiolate ligands are cis and the nitrogen ligands include one amide and one amine.21 Our current studies support a possible arrangement that parallels the coordination by Ni-SOD in which the two sulfur ligands are arranged cis and one nitrogen is derived from a backbone amide while the second is from the N-terminal amine (Figure 2). DFT computations22 show that this proposed structure has the lowest total energy when compared with other potential structures with different nitrogen coordination environments and other cis and trans configurations (Supporting Information).

Figure 2.

Metal coordination in Ni-SOD (right) and the proposed coordination in Ni-NCC (left). Wavy lines indicate the connection to the rest of the protein.

To probe whether or not the the Asn side chain is involved in Ni(II) coordination, the tripeptide GCC was synthesized and transmetallated. The observation that the Ni-GCC spectra parallel those of Ni-NCC supports the structure proposed above, where the Asn side chain is not ligated to the Ni(II) center. GGNCC and GGGCC peptides were also synthesized to further examine the identity of the nitrogen ligands in Ni-NCC. The spectral features of the pentapeptides are similar to each other but differ from the tripeptides (Supporting Information). This suggests the N-terminal amine participates in metal coordination in the tripeptides. Presumably, the N-terminal amine in the pentapeptides is too far removed from the Ni(II) center to act as a ligand and the backbone amide nitrogen from the Asn substitutes for the terminal amine nitrogen to accomplish metal binding. Additionally, it is thought that mixed amine/amide coordination species are more stable to oxygenation than bis-amide species,15 and the observation that Ni-NCC does not experience oxidation of the S ligands is further evidence for the proposed mixed amine/amide coordination. Similarities in the chemistry (vide infra) support the use of Ni-NCC as a model system for understanding the catalytic mechanism of Ni-SOD.

Because the studies above demonstrate that Ni-NCC serves as a reasonable structural mimic of Ni-SOD, the midpoint potential of Ni-NCC was measured using cyclic voltammetry (CV). CV data show electron transfer is quasi- reversible, with a midpoint potential of 0.72(2) V versus Ag/AgCl (Supporting Information), which is similar to the 0.70(2) V measured for a peptide mimic based on the sequence of the parent enzyme with mixed amine/amide coordination and cis ligation ([Ni(SODM1]).17 Ni-SOD has a midpoint potential of 0.290 V (NHE, 0.093 versus Ag/AgCl).10 The quasi-reversibility of the CV data indicate structural changes upon oxidation/reduction, which is rationalized in terms of the different geometries preferred by Ni(II) and Ni(III) centers. To confirm that electron transfer does not alter the peptide and the measured potential specifically reflects a change at the nickel ion, ESI-MS was collected after performing bulk electrolysis. The mass is the same before and after undergoing oxidation, implying the peptide is unaltered. Therefore, the redox potential measured corresponds to the Ni(II)/Ni(III) redox couple. Because the midpoint potential of the Ni-NCC complex falls between the reduction and oxidation potentials for superoxide, the ability of Ni-NCC to dismutate the reactive superoxide species was examined.

A standard SOD activity assay using xanthine oxidase was performed.23,24 The data show that Ni-NCC does exhibit SOD activity, but it is slower than Ni-SOD. The IC50 for Ni-NCC (4.1 ± 0.8 × 10−5 M) is comparable to those values reported for other peptide mimics, particularly the maquette with bis-amide nitrogen coordination (3 × 10−5 M).18

Because the reduction potential of Ni-NCC is similar to that of [Ni(SODM1], but the activity of Ni-NCC is lower than this amine/amide maquette (2.1 × 10−7 M),18 the rate may be decreased by the absence of a fifth ligand in the Ni-NCC complex. For Ni-SOD, it has been suggested that the axial imidazole ligand tunes the redox properties of the Ni(III) species to be appropriate for superoxide dismutation.19,21 In follow-up studies to be presented elsewhere, examination of the system in the presence of anions showed that Ni-NCC coordinates a transient, anionic fifth ligand, further supporting its similarity to Ni-SOD.

Ni-NCC exhibits similar features to Ni-SOD, and its midpoint potential and ability to break down superoxide support its use as a mimic of the enzyme. The sequence of this novel peptide mimic is unrelated to that of Ni-SOD and provides a complimentary system for understanding how the identity and geometry of the supporting ligands influence not only the reduction potential but functional electron transport.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. C. Schöneich and V. Sharov for input on the xanthine oxidase assay, and Drs. S. Lunte and M. Hulvey and C. Kuhnline for assistance with CV. This work was supported by J.R. and Inez Jay Fund (Higuchi Biosciences Center). MK is funded by the Madison and Lila Self Graduate Fellowship. AG is funded by the NIH Dynamic Aspects of Chemical Biology Training Grant (T2 GM GM08454).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Experimental procedures and ESI-MS, pH titration, MCD, DFT, CV, and control peptide data. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Bryngelson PA, Maroney MJ. Met Ions Life Sci. 2007;2:417–443. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller AF. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2004;8:162–168. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2004.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Youn HD, Kim EJ, Roe JH, Hah YC, Kang SO. Biochem J. 1996;318:889–896. doi: 10.1042/bj3180889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Youn HD, Youn H, Lee JW, Yim YI, Lee JK, Hah YC, Kang SO. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1996;334:341–348. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1996.0463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Szilagyi RK, Bryngelson PA, Maroney MJ, Hedman B, Hodgson KO, Solomon EI. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:3018–3019. doi: 10.1021/ja039106v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wuerges J, Lee JW, Yim YI, Yim HS, Kang SO, Carugo KD. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:8569–8574. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308514101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barondeau DP, Kassmann CJ, Bruns CK, Tainer JA, Getzoff ED. Biochemistry. 2004;43:8038–8047. doi: 10.1021/bi0496081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choudhury SB, Lee JW, Davidson G, Yim YI, Bose K, Sharma ML, Kang SO, Cabelli DE, Maroney MJ. Biochemistry. 1999;38:3744–3752. doi: 10.1021/bi982537j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bryngelson PA, Arobo SE, Pinkham JL, Cabelli DE, Maroney MJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:460–461. doi: 10.1021/ja0387507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herbst RW, Guce A, Bryngelson PA, Higgins KA, Ryan KC, Cabelli DE, Garman SC, Maroney MJ. Biochemistry. 2009;48:3354–3369. doi: 10.1021/bi802029t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gale EM, Patra AK, Harrop TC. Inorg Chem. 2009;48:5620–5622. doi: 10.1021/ic9009042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schmidt M, Zahn S, Carella M, Ohlenschlaeger O, Goerlach M, Kothe E, Weston J. ChemBioChem. 2008;9:2135–2146. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200800017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tietze D, Breitzke H, Imhof D, Koeth E, Weston J, Buntkowsky G. Chem--Eur J. 2009;15:517–523. doi: 10.1002/chem.200800870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ma H, Chattopadhyay S, Petersen JL, Jensen MP. Inorg Chem. 2008;47:7966–7968. doi: 10.1021/ic801099r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shearer J, Zhao N. Inorg Chem. 2006;45:9637–9639. doi: 10.1021/ic061604s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stibrany RT, Fox S, Bharadwaj PK, Schugar HJ, Potenza JA. Inorg Chem. 2005;44:8234–8242. doi: 10.1021/ic050114h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shearer J, Long LM. Inorg Chem. 2006;45:2358–2360. doi: 10.1021/ic0514344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neupane KP, Shearer J. Inorg Chem. 2006;45:10552–10566. doi: 10.1021/ic061156o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neupane KP, Gearty K, Francis A, Shearer J. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:14605–14618. doi: 10.1021/ja0731625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.A minor paramagnetic component is observed that represents less than 1% of the sample. The presence of this component has complicated 1H-NMR experiments.

- 21.Fiedler AT, Bryngelson PA, Maroney MJ, Brunold TC. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:5449–5462. doi: 10.1021/ja042521i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Neese F. ORCA – an ab initio, Density Functional and Semiempirical Program Package, Version 2.7. University of Bonn; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crapo JD, McCord JM, Fridovich I. Methods Enzymol. 1978;53:382–393. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(78)53044-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tabbi G, Driessen WL, Reedijk J, Bonomo RP, Veldman N, Spek AL. Inorg Chem. 1997;36:1168–1175. doi: 10.1021/ic961260d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.