Abstract

We showed previously that deliberate immunization of BALB/c mice with immune complexes (IC) of the cariogenic bacterium Streptococcus mutans and monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) against its surface adhesin P1 results in changes in the specificity and isotype of elicited anti-P1 antibodies. Depending on the MAb, changes were beneficial, neutral, or detrimental as measured by the ability of the serum from immunized mice to inhibit bacterial adherence to human salivary agglutinin by a BIAcore SPR assay. The current study further defined changes in the host response that result from immunization with IC containing beneficial MAbs and evaluated mechanisms by which beneficial immunomodulation could occur in this system. Immunomodulatory effects varied depending upon genetic background with differing results in C57/BL6 and BALB/c mice. Desirable effects following IC immunization were observed in the absence of activating Fc receptors in BALB/c Fcer1g transgenic mice. MAb F(ab)2 fragments mediated desirable changes similar to those observed using intact IgG. Sera from IC-immunized BALB/c mice that were better able to inhibit bacterial adherence demonstrated an increase in antibodies able to compete with an adherence-inhibiting anti-P1 MAb, and binding of a beneficial immumomodulatory MAb to S. mutans increased exposure of that epitope. Consistent with a mechanism involving a MAb-mediated structural alteration of P1 on the cell surface, immunization with truncated P1 derivatives lacking segments that contribute to recognition by beneficial immunomodulatory MAbs resulted in an improvement in the ability of elicited serum antibodies to inhibit bacterial adherence compared to immunization with the full-length protein.

Keywords: Rodent, Vaccination, Bacterial, Antibodies, Epitopes

Introduction

Streptococcus mutans (S. mutans) is the primary etiologic agent of dental caries in humans (1), a common infectious disease in the United States and worldwide. A number of virulence factors of S. mutans have been studied as vaccine candidates (2–5). The focus of the current study is a Mr~185,000 protein of S. mutans serotype c called P1. Originally identified as Antigen I/II (6), and also called Antigen B or PAc (7), it is a member of a family of structurally complex cell-surface anchored multi-functional adhesins. P1-like polypeptides are produced by almost all species of oral streptococci indigenous to the human oral cavity and mediate interactions with salivary constituents, host cell matrix proteins such as fibronectin, fibrinogen, collagen, and other oral bacteria (8). P1 contains a series of alanine-rich repeats (A-region), a variable region where most sequence variations between P1 from different bacterial strains are clustered, a series of proline-rich repeats (P-region), and carboxy-terminal sequences characteristic of wall and membrane spanning domains of streptococcal surface proteins (Figure 1A).

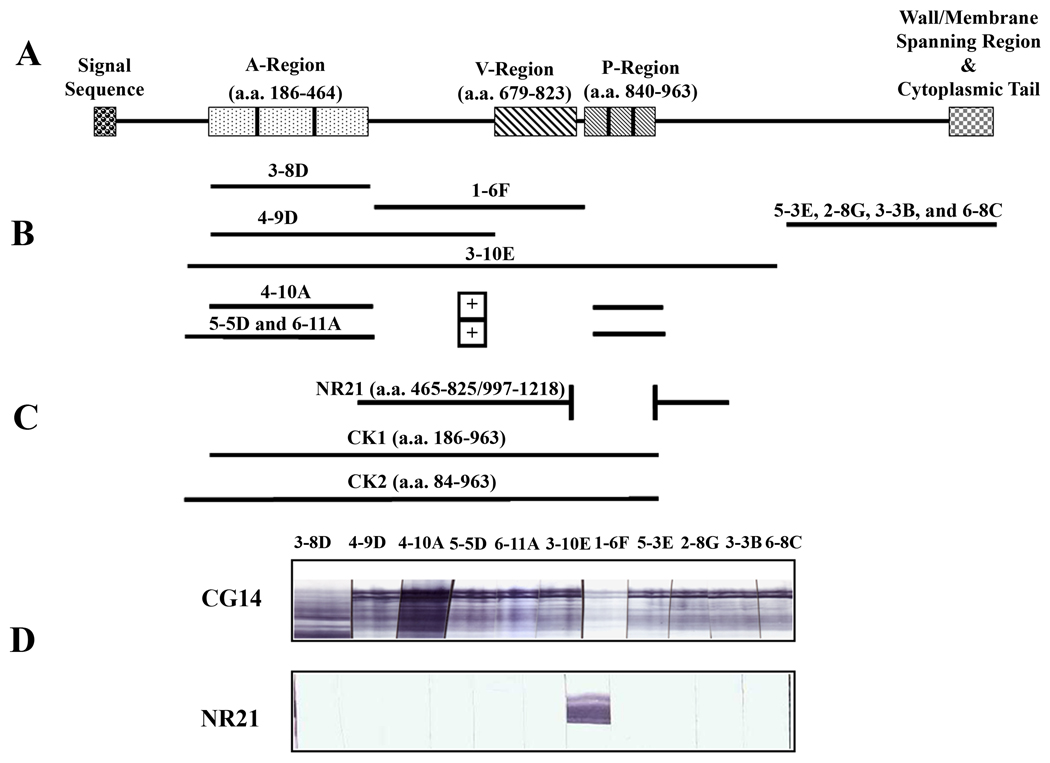

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of P1 and regions contributing to epitope formation. (A) Schematic representation of the primary sequence of P1 and its relevant domains. (B) Segments of P1 or combinations thereof currently known to achieve epitopes recognized by a panel of eleven different anti-P1 MAbs. Anti-P1 MAbs that map to the C-terminus of P1 are not reactive with whole bacterial cells. MAb 3-8D reacts predominantly with breakdown products of P1 as well as with a sub-cloned A-region polypeptide. It is also poorly reactive with whole bacterial cells. (C) Schematic representation of recombinant P1 polypeptides NR21, CK1 and CK2. The in-frame deletion construct NR21 was initially generated during studies to evaluate the contribution of the P-region to P1 epitopes. (D) Reactivity of anti-P1 MAbs with CG14 (full-length recombinant P1) and polypeptide NR21 by Western Blot.

An important physiologic ligand of P1 contained within the salivary pellicle is the large molecular weight glycoprotein called salivary agglutinin (SAG) (9–12), now known to represent the human salivary scavenger protein glycoprotein 340 (gp340) (13). The interaction of P1 with salivary components is complex (14) and different regions of P1 are involved in its interaction with human SAG depending on whether SAG is in fluid-phase or immobilized on a surface (9).

Humoral immunity against dental caries in animal models and naturally sensitized humans has been reported for many years (reviewed in (2, 15). P1 (Antigen I/II, PAc), has been studied in both active and passive immunization approaches, but a definitive correlate of protection particularly at the epitope level has not yet been fully elucidated. Numerous reports have stated that salivary and serum antibodies, including those against P1, can be both protective or non-protective depending on the study (16–22). Collectively these studies suggest that the fine specificity of the immune response is an important determinant in clinical outcome. There is long-standing and recent evidence that passively administered Ab may not be entirely passive, but can also have immunomodulatory effects (23–26). Deliberate immunization with Ag bound by Ab can result in suppression, enhancement, and differences in the elicited immune response and exogenously applied Ab has been reported to act as a therapeutic agent by redirecting the host immune response (27). Numerous changes in immune responses against antigen coupled with monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) have been documented (28–31) although the mechanism(s) mediating such changes are not completely understood and likely overlap and vary depending on the system.

Previous studies in our laboratory identified six different anti-P1 IgG1 MAbs that influence the anti-P1 response when they are bound to the surface of S. mutans whole cells and administered intraperitoneally to BALB/c mice as part of an immune complex (IC) (32–34). Differences in the immune response include changes in the ability of sera from IC-immunized mice to inhibit S. mutans adherence to SAG, measured using a whole cell BIAcore surface plasmon resonance (SPR) assay, as well as changes in the specificity and isotype of anti-P1 antibodies elicited in mice receiving IC compared to S. mutans alone. Anti-P1 MAbs are not equal in their ability to inhibit adherence of S. mutans to SAG or in their ability to modulate the immune response against P1. The minimal primary sequence of P1 currently known to achieve each cognate epitope has been characterized (Figure 1B) (35–38).

Anti-P1 MAbs 6-11A, 3-10E, and 5-5D are beneficial modulators of humoral immunity in that they promote a polyclonal anti-S. mutans antibody response more inhibitory of bacterial adherence to immobilized SAG. These MAbs themselves, that will hereon be referred to as beneficial immunoodulatory MAbs, do not inhibit adherence (34). In contrast, MAbs 1-6F and 4-9D inhibit adherence and map to the segment of P1 intervening the A- and P-regions, but promote the formation of a polyclonal response less inhibitory of adherence when they are administered as part of an IC. MAb 4-10A also inhibits adherence and was initially found to be neutral with regard to its influence on the adherence inhibiting response (34), although in the current study we found that 4-10A demonstrates a notable prozone-like effect and promotes a beneficial response in a concentration-dependent manner.

It was the purpose of the current study to continue to identify specific changes in the murine serum response mediated by beneficial immunomodulatory anti-P1 MAbs and to evaluate factors that contribute to their desirable outcome. To that end the roles of host genetic background, activating Fc receptors and MAb Fc on immunomodulation were evaluated. The ability of serum from immunized mice to inhibit adherence of S. mutans to immobilized SAG, to compete for binding of the known adherence-inhibiting MAb 1-6F, and the isotype composition of 1-6F-like antibodies were used as measures of specific immunomodulatory changes resulting from IC-immunization, and the ability of an immunomodulatory MAb to influence exposure of the 1-6F epitope on the bacterial surface was explored. Lastly, to confirm whether desirable effects may result from a destabilizing effect on protein structure and an enhanced response against relevant target epitopes that may be revealed upon binding of beneficial anti-P1 MAbs to S. mutans, mice were immunized with truncated P1 variants that had been engineered to lack segments of P1 that contribute to their complex discontinuous epitopes.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial strains, plasmids and growth conditions

Serotype c S. mutans strain NG8 was grown aerobically to stationary phase for 16 hr in Todd-Hewitt broth supplemented with 0.3% yeast extract (BBL, Cockeysville, MD). The Escherichia coli (E. coli) host strains used to express recombinant P1 polypeptides were DH5α (InVitrogen Corp., San Diego, CA) and M15 (pREP4) (Qiagen, Santa Clarita, CA). E. coli strains were grown aerobically at 37°C with vigorous shaking in Luria-Bertani broth (1% [wt/vol] tryptone, 0.5% [wt/vol] yeast extract, 1% [wt/vol] NaCl) supplemented with ampicillin (50–100 µg/mL) or kanamycin (25–50 µg/mL) as appropriate. Plasmids pCR2.1 (InVitrogen Corp) and pMalp (New England Biolabs, Inc. [NEB], Beverly, MA) were used as cloning and expression vectors.

Construction and purification of P1 polypeptide NR21

Plasmid pNR21 was derived by PCR amplification as described (36) using forward primer 5’-GGG-GAGTACTGATTTAGCAGACTATCCA-3’ and reverse primer 5’-GGGTCGACTCAGTCAGTCAATCCTGACGCAATTCAAG-3’ with the spaP-derived P-region deletion construct pCG2 (39) plasmid DNA as the template. spaP is the gene that encodes P1. Underlined sequences indicate ScaI and SalI restriction sites engineered into the forward and reverse primers, respectively, and were included for subsequent cloning into pMal-p and expression of the P1-derived polypeptide as a fusion partner with maltose binding protein (MBP). NR21 was initially constructed to evaluate the contribution of the P-region and sequences flanking it to epitopes recognized by anti-P1 MAbs. E. coli containing pNR21 was grown as described (36). Overnight cultures were diluted 1:100 into fresh media containing ampicillin (50–100 µg/mL), grown with shaking to OD600 of 0.45–0.6 and induced for 3–5 hours at 37°C with 0.1–0.5 mM IPTG (Fisher). The fusion protein was affinity purified from E. coli lysates by column chromatography using amylose resin (New England Biolabs, Inc. [NEB], Beverly, MA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Mice

Six-eight week old female BALB/c and C57/BL6 mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA. Four-twelve week old male and female Fcer1g (FcRγ) transgenic mice were purchased from Taconic Laboratories, Hudson, NY. Mice were housed in biosafety level 2 facilities under infectious disease conditions and fed a standard diet. Animal experiments were conducted under the auspices of the University of Florida Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Source of antibodies

Anti-P1 MAbs were obtained from previously established hybridomas made in our laboratory (40). All MAbs used in this study were purified by column chromatography from ascites fluid using an ImmunoPure (A Plus) IgG Purification Kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Peroxidase-labeled and unlabeled secondary MAb reagents were obtained from Southern Biotech (Birmingham, AL).

Pepsin digestion of MAbs and purification of F(ab)2 Fragments

MAbs 5-5D and 6-11A were buffer exchanged into 0.2 M Sodium Acetate adjusted to pH 4.0 using glacial acetic acid, diluted or concentrated to ~ 2.0 mg/ml, and 0.1 mg/ml pepsin (Sigma) dissolved in the same buffer was added to achieve an enzyme:Ab ratio of 1:20. Samples were incubated at 37°C for 24–72 hours followed by addition of 2 M Tris base until the pH reached 7.0–8.0 and then dialyzed overnight into 1× PBS, pH 8.0. The digestion mixtures were depleted of Fc fragments and residual undigested MAb using an ImmunoPure (A Plus) IgG Purification Kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The protein A column was equilibrated with binding buffer and the digested sample was diluted 1:1 in binding buffer and applied. Flow through and the first wash containing Fc-free F(ab)2 fragments were collected. Final purification of F(ab)2 fragments was performed on a Bio-silect 250 gel filtration column (Bio Rad, Hercules, CA). Purity of F(ab)2 was verified by Western blot using anti-Fc, anti-γ chain, anti-κ chain, and anti-λ chain specific secondary antibodies (Southern Biotech).

Immunizations and sample collections

Groups of six mice were immunized intraperitoneally (IP) with ~1.5 × 109 CFUs of S. mutans in 150 µl of PBS or the same amount of S. mutans coated with either a saturating (high) or 0.1× sub-saturating (low) concentration of each MAb (34) or with MAb-derived F(ab)2 fragments. The dilution of MAb or F(ab)2 fragments necessary to saturate an equal volume of the standardized concentration of bacterial cells was predetermined by serial titration and dot blot analysis. In the case of 4-10A a dilution of 1:2000 of 3 mg/ml of the purified MAb represented a 0.1× sub-saturating antibody concentration and S. mutans cells were reacted with 2-fold serial dilutions of MAb beginning at that point. To exclude the possibility of anti-idiotype effects and to control for other potential effects of MAbs that might occur independently of antigen, additional control groups of mice received MAb alone at the concentration required to saturate the immunizing dose of bacteria. Sera from these mice were not reactive with P1 or S. mutans, nor were pre-bleed sera from experimental groups or sera from negative control mice that received buffer only (data not shown). Mice were pre-bled one week before the first inoculation, immunized on days 0 and 14 and exsanguinated on day 30–40. Interim bleeds were also taken on day 7 in some cases. All experiments were performed with terminal serum collections unless stated otherwise.

For experiments with P1 and truncated derivatives, groups of five mice were immunized intraperitoneally (IP) with emulsified polyacrylamide gel slices containing recombinant full-length P1 (CG14), or with recombinant P1 polypeptides CK1, CK2 (38) or NR21 (this study) expressed as fusion proteins with MBP. Negative control groups received MBP alone, acrylamide only, or PBS alone. E. coli containing pCG14, pCK1, and pCK2, pNR21 or pMAL-p vector alone was grown as described (36). Overnight cultures were diluted 1:100 into fresh media containing ampicillin (50–100 µg/mL) for CK1, CK2, NR21, and MBP control, or containing ampicillin (50–100 µg/mL) and kanamycin (25 µg/mL) for CG14, grown with shaking to OD600 of 0.45–0.6 and induced for 3–5 hours at 37°C with 0.1–0.5 mM IPTG (Fisher). Cells were harvested by centrifugation, boiled in SDS sample buffer and lysates were loaded onto 7.5% SDS-polyacrylamide gels. Gels were negatively stained with 0.3 M cupric chloride for 5 minutes then rinsed with water. Negative stained bands of the correct size and corresponding to ~ 10 µg total protein were excised and de-stained with 0.25 M EDTA, 0.25 M Tris, pH 9 by incubating 3× for 10 minutes at room temperature with a final exchange into PBS. The gel slices containing each recombinant protein were emulsified into approximately 1 mL of PBS and 100 µL was used to immunize individual mice. Mice were pre-bled one week before the first inoculation, immunized on days 0 and 14 and exsanguinated on day 36. All immunization experiments were performed under the guidelines and approved by the University of Florida Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

BIAcore assay of S. mutans adherence to salivary agglutinin

Adherence of S. mutans whole cells to human salivary agglutinin immobilized on a CM3 sensor chip (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) was measured using the BIAcore 3000 machine (BIAcore AB, Uppsala, Sweden) as previously described (33). Salivary agglutinin was prepared by a modification of the technique of Rundegren and Arnold (9, 41). Adherence of S. mutans cells pretreated with serum from mice immunized with bacteria alone versus those immunized with IC were compared in each experiment.

Western Blot reactivity of anti-P1 antibodies with NR21 and full-length P1

Recombinant full-length P1 (39) or recombinant polypeptide NR21 was electrophoresed on replicate 7% SDS-polyacrylamide preparatory slab gels and electroblotted onto nitrocellulose filters. Filters were blocked with PBS containing 0.3% Tween20, cut into strips and replicate strips were reacted with each of the 11 different anti-P1 MAbs. Blot strips were washed, reacted with affinity-purified peroxidase-labeled goat anti-mouse peroxidase-conjugated IgG specific antibody (Southern Biotech, AL) and developed with 4-chloro-1-naphthol substrate solution. Control blot strips were reacted with secondary antibody only (not shown).

Biotin-labeling of MAb 1-6F and competition ELISA

Approximately 1 mg of purified anti-P1 MAb 1-6F was labeled with biotin using EZ-Link™ Biotin-LC-Hydrazide (Pierce, Rockford, IL) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. ELISA plate wells were coated with S. mutans whole cells (~107 cfu/well) (40) in carbonate-bicarbonate buffer, pH 9.6. To determine the optimal dilution for each competition experiment immune sera from S. mutans or IC-immunized mice were serially diluted three-fold beginning at 1:100 and added to the wells followed by biotin-labeled MAb 1-6F and incubated at 37°C for two hours. Plates were washed and avidin-HRP conjugate (Pierce, IL) was applied to the wells for 30 minutes at room temperature. Plates were washed again and developed with 0.1 M o-phenylenediamine dihydrochloride containing 0.012% hydrogen peroxide in 0.01M phosphate citrate buffer. Optimal working dilutions ranged from 1:300 to 1:900. Percent inhibition of biotin-labeled MAb 1-6F binding was calculated as % Inhibition = [OD450 direct binding of biotin-labeled 1-6F - OD450 experimental well/OD450 direct binding of biotin-labeled 1-6F] × 100. Control wells contained non-labeled MAb 1-6F and avidin-HRP.

Quantitative subclass ELISA

Serum samples were assayed for anti-S. mutans or anti-P1 polypeptide NR21 IgG1, IgG2a, and IgG2b isotype antibodies by quantitative subclass ELISA. Sera from C57/BL6 mice were assayed for IgG2c instead of IgG2a (42). ELISA plate wells were coated with NG8 whole cells or 200 ng/well purified recombinant NR21 in carbonate-bicarbonate buffer, pH 9.6. Murine sera were serially diluted two-fold beginning at 1:50 and added to the wells. Antibody reactivity was detected using affinity-purified peroxidase-labeled goat anti-mouse peroxidase conjugated IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b, or IgG2c subclass specific antibodies (Southern Biotech) at a 1:1000 dilution. Plates were developed with 0.1 M o-phenylenediamine dihydrochloride containing 0.012% hydrogen peroxide in 0.01M phosphate citrate buffer. The concentrations of anti-S. mutans or anti-NR21 IgG subclass antibodies were calculated by interpolation on standard curves generated using purified mouse subclass reagents (Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL).

Results

The genetic background of the host affects immunomodulation by anti-P1 MAbs

The protective efficacy of exogenously-administered antibodies has been shown to differ depending on the genetic background of the murine host and underscores the potential complexity of antibody-mediated effects on the subsequent adaptive immune response (43). To determine whether immunomodulation by anti-P1 MAbs is influenced by genetic background, immunization experiments were performed in BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice. Mice were immunized in parallel with uncoated S. mutans whole cells or with IC containing MAbs 6-11A or 5-5D at saturating or 0.1× sub-saturating concentrations. As observed in our previous studies, BIAcore SPR assays demonstrated that sera from BALB/c mice immunized with ICs containing MAbs 6-11A and 5-5D were increased in their ability to interfere with bacterial adherence to immobilized SAG; however, the results were not identical in C57BL/6 mice treated in an identical manner (Figure 2A).

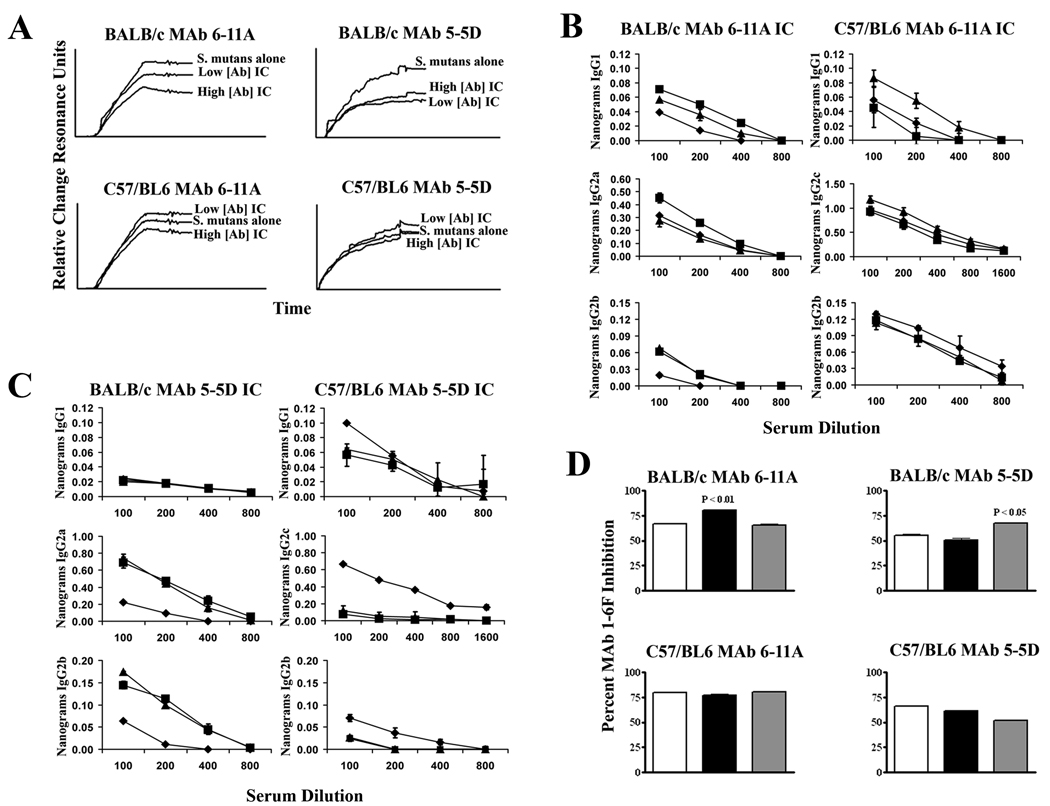

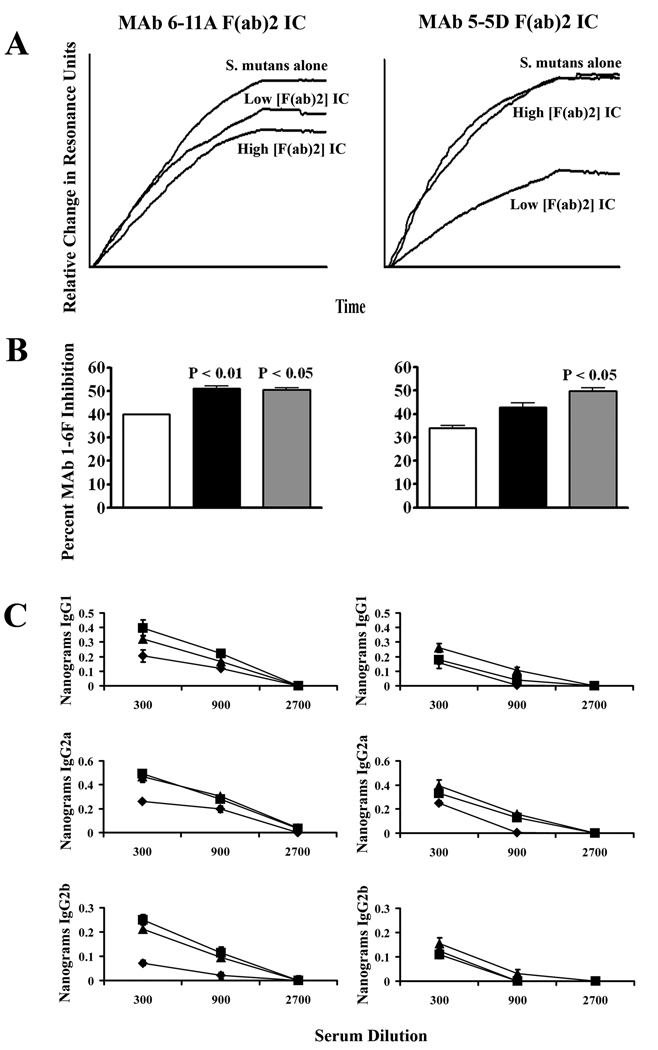

Figure 2.

Host genetic background affects beneficial immunomodulation. (A) BIAcore SPR analysis of S. mutans adherence to immobilized salivary agglutinin. Sensograms show the binding of S. mutans to immobilized SAG in the presence of serum from BALB/c or C57/BL6 mice immunized with S. mutans alone or with IC containing MAbs 6-11A or 5-5D at high (saturating) or low (0.1× sub-saturating) concentrations. (B) Evaluation of IgG subclasses reactive with anti-S. mutans whole cells. Sera collected 7 days after primary immunization from BALB/c or C57/BL6 mice immunized with S. mutans alone (diamonds), IC containing MAb 6-11A at the higher concentration (squares), or lower concentration (triangles) were evaluated by quantitative ELISA. (C) Same as panel B except that MAb 5-5D was used in the experiment. (D) A competition ELISA was used to determine the level of MAb 1-6F-like Abs in the serum of BALB/c and C57/BL6 mice immunized with ICs of MAb 6-11A and 5-5D compared to S. mutans alone. The percent inhibition of binding of biotin-labeled 1-6F to S. mutans by sera from mice immunized with bacteria alone (white bars), high MAb concentration IC (black bars), and low MAb concentration IC (grey bars) is indicated. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM and statistical significance compared to serum from S. mutans only immunized mice is indicated by P values. Data are representative of at least three independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using graph pad prism 4.0 and analysis included one-way anova.

The sera from the immunized BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice were also examined for changes in the isotype composition of the anti-S. mutans response. To evaluate the immune response in these mice early after exposure to antigen, sera collected 7 days after the primary immunization were assayed by quantitative ELISA. Compared to serum from mice that received S. mutans alone, the serum from BALB/c mice immunized with ICs containing MAb 6-11A showed an increase in anti-S. mutans IgG1 and IgG2b at both MAb concentrations, and in IgG2a at the high MAb concentration (Figure 2B). Again the results in the C57BL/6 mice were different from those in the BALB/c mice with the most pronounced effect seen with IgG1 at the low MAb concentration in the C57/BL6 mice. The sera from BALB/c mice immunized with ICs containing MAb 5-5D also contained increased levels of anti-S. mutans antibodies of the IgG2a and IgG2b isotypes compared to the serum from the S. mutans-immunized mice while the sera from the C57BL/6-immunized did not demonstrate the same 5-5D MAb-mediated effects (Figure 2C).

Several anti-P1 MAbs inhibit the binding of S. mutans to immobilized SAG (23, 34). Therefore one would predict that the sera from 6-11A and 5-5D IC-immunized mice that had demonstrated an increased ability to inhibit bacterial adherence would also contain increased levels of antibodies that recognize similar epitopes as adherence-inhibiting MAbs. To explore this possibility, the ability of the sera from S. mutans and IC-immunized BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice to compete with the adherence-inhibiting MAb 1-6F for binding to P1 on the surface of S. mutans whole cells was compared by competition ELISA. Sera from 6-11A and 5-5D IC-immunized BALB/c mice, at the high and low MAb concentrations respectively, but not the C57BL/6 mice, demonstrated increased levels of antibodies capable of competing with biotin-labeled 1-6F for S. mutans binding over the serum from mice that had received bacteria alone (Figure 2D).

These results confirmed our previous findings that 6-11A and 5-5D redirect the humoral immune response in BALB/c mice towards one of increased efficacy in terms of the ability of elicited antibodies to functionally inhibit bacterial adherence to a known receptor. We also extended these findings to identify MAb-mediated changes in the IgG subclass composition of anti-S. mutans serum antibodies during the initial immune response and we further characterized the change in antibody specificity that accompanied the change in biological activity. That the same effects were not observed in the C57BL/6 strain indicates that the MAbs alter the subsequent immune response by a mechanism that is influenced by the genetic background of the host.

Further evaluation of competition against MAb 1-6F by sera from IC-immunized mice

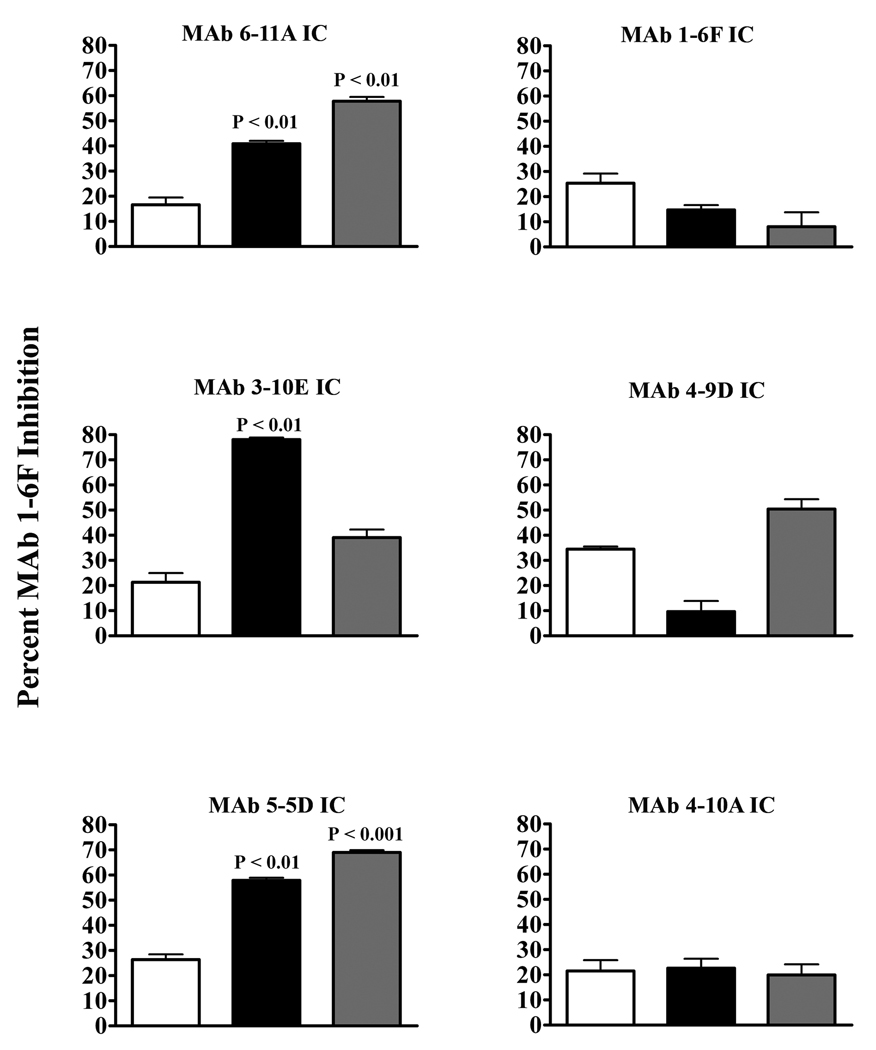

With the new information that immunization with IC containing MAbs 6-11A and 5-5D promotes a polyclonal immune response that contains increased levels of antibodies capable of competing for S. mutans binding with biotin-labeled 1-6F, additional competition experiments were undertaken. Previously, MAbs 6-11A, 3-10E, 5-5D, 1-6F, 4-9D, and 4-10A had all been tested for immunomodulatory activity when administered to BALB/c mice as part of an IC. Sera from the 6-11A, 3-10E, and 5-5D, but not the 1-6F, 4-9D or 4-10A IC-immunized mice had demonstrated an increased ability to inhibit S. mutans binding to immobilized SAG by BIAcore assay (32, 34). Therefore, sera stored from these prior experiments were tested for their ability to compete for S. mutans binding with biotin-labeled MAb 1-6F.

The sera from the mice that had been immunized with IC containing MAbs 6-11A, 3-10E, and 5-5D all demonstrated significantly higher levels of antibodies able to compete with MAb 1-6F for binding to S. mutans compared to sera from S. mutans-immunized mice (Figure 3). In contrast, sera from mice that had been immunized with IC containing those MAbs shown not to promote an adherence inhibiting response did not exhibit an increase in 1-6F-like antibodies. These data demonstrate a link between the previously identified beneficial immunomodulatory MAbs and the promotion of an enhanced response against a relevant target epitope.

Figure 3.

MAb 1-6F competition by sera from anti-P1 MAb IC-immunized BALB/c mice. Competition ELISA was used to evaluate the presence of MAb 1-6F-like Abs in the sera of BALB/c mice immunized with ICs containing MAbs 6-11A, 3-10E, 5-5D, 1-6F, 4-9D, or 4-10A versus S. mutans alone. The percent competition by sera from mice immunized with S. mutans alone (white bars), IC containing the high (saturating) MAb concentration (black bars), or IC containing the low (0.1× sub-saturating) MAb concentration (grey bars) is indicated. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM and statistical significance compared to serum from S. mutans only immunized mice is indicated by P values. Data are representative of at least three independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using graph pad prism 4.0 and analysis included one-way anova.

Activating Fc receptors are not required for beneficial immunomodulation by an Anti-P1 MAb

Major mechanisms by which antibody has been reported to exert immunomodulatory effects are by way of promotion of uptake of antigen via Fc receptors (FcRs) on antigen presenting cells and/or differential engagement of stimulatory versus inhibitory FcRs (29). To evaluate whether FcRs play a critical mechanistic role in anti-P1 MAb-mediated effects an immunization experiment was carried out in mice lacking activating Fc receptors. The three receptors known to bind IgG and activate an immune response, FcγRI, FcγRIII, and FcγRIV, all depend upon a common γ chain for signaling through an ITAM motif. The FcγR targeted mutation in the Fcer1g transgenic mouse lacks a functional γ chain (44). BALB/c background Fcer1g mice were immunized with S. mutans alone or with IC containing MAb 5-5D at either saturating or 0.1× sub-saturating concentrations. Sera from both groups of IC-immunized mice were better able to interfere with adherence of S. mutans to immobilized SAG compared to mice that were immunized with S. mutans alone and demonstrated that activating FcRs are not necessary for the ability of the MAb to promote this desirable response (Figure 4A). Furthermore, the sera from the IC-immunized mice demonstrated increased competition of biotin-labeled MAb 1-6F binding to P1 on the surface of S. mutans compared to the serum from S. mutans-immunized mice (Figure 4B).

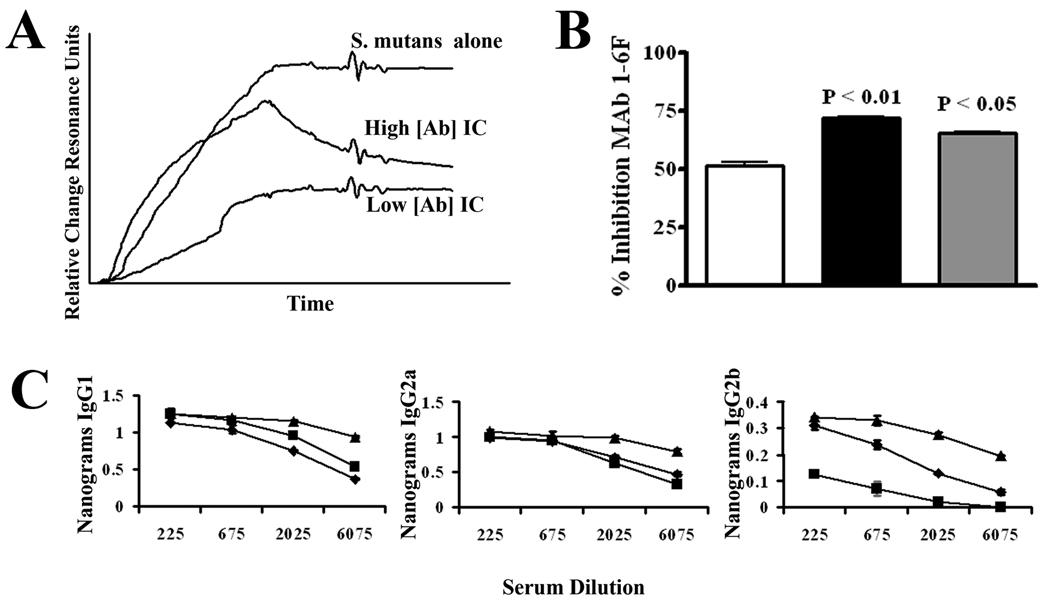

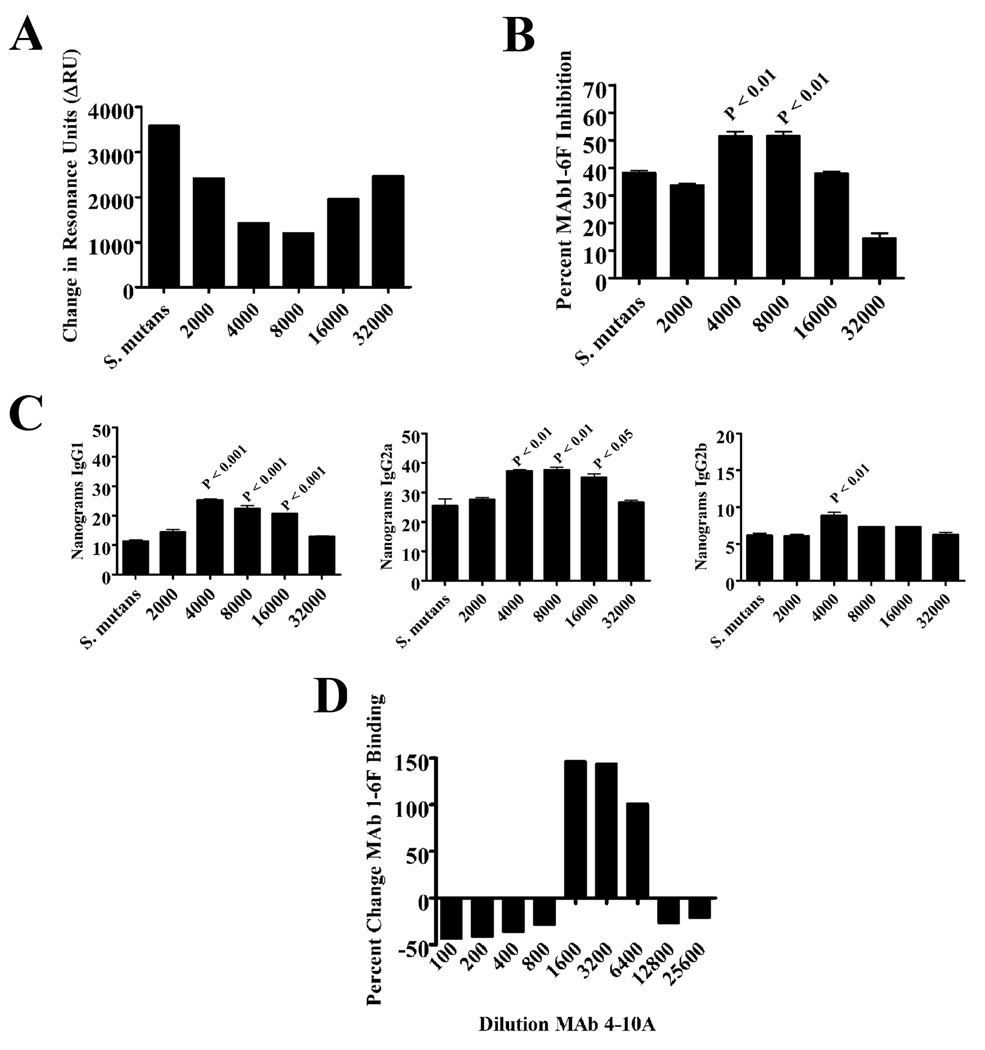

Figure 4.

Evaluation of the role of activating Fc receptors in beneficial immunomodulation by anti-P1 MAbs. (A) BIAcore SPR analysis of S. mutans adherence to immobilized salivary agglutinin. Sensograms show the binding of S. mutans to immobilized SAG in the presence of serum from Fcer1g transgenic mice immunized with S. mutans alone or with IC containing high (saturating) or low (0.1× sub-saturating) concentrations of MAb 5-5D. (B) MAb 1-6F competition ELISA. The percent competition by sera from mice immunized with S. mutans alone (white bars), IC containing the high (saturating) MAb concentration (black bars), or IC containing the low (0.1× sub-saturating) MAb concentration (grey bars) is indicated. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM and statistical significance compared to serum from S. mutans only immunized mice is indicated by P values. (C) Quantitative anti-NR21 IgG subclass ELISA. Levels of anti-NR21 specific IgG1, IgG2a, and IgG2b subclass antibodies were measured in sera collected from Fcer1g transgenic mice immunized with S. mutans alone (diamonds), or with IC containing MAb 5-5D at the high saturating (squares) or low 0.1× sub-saturating concentration (triangles). Results are expressed as mean ± SEM and statistical significance compared to serum from S. mutans only immunized mice is indicated by P values. Data are representative of at least three independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using graph pad prism 4.0 and analysis included one-way anova.

Since prior studies in our laboratory had demonstrated a statistically significant correlation between the ability of serum from IC-immunized mice to inhibit bacterial adherence to immobilized SAG and the levels of IgG2a and IgG2b reactive with S. mutans (34), we also wished to evaluate the isotype of antibodies that were able to compete with biotin-labeled 1-6F-for binding and to determine whether IgG2a and/or IgG2b subclasses were among those increased. To that end a quantitative subclass ELISA was employed using as the antigen recombinant P1 polypeptide NR21 that is recognized by MAb 1-6F but none of the other anti-P1 MAbs in our panel (Figure 1C and 1D). Increased levels of anti-NR21 IgG1, IgG2a and IgG2b were observed in the sera of MAb 5-5D IC-immunized Fcer1g mice compared to the serum from S. mutans-immunized Fcer1g mice and were most notable for the IgG2b isotype. Taken together these results indicate that desirable immunomodulatory effects of a beneficial anti-P1 MAb can occur independently of the presence of activating FcRs.

The Fc portion of anti-P1 MAbs is not required for immunomodulation

Despite ruling out an apparent role of activating Fc receptors in the mechanism underlying beneficial immunomodulation by anti-P1 MAbs we wished to rule out the necessity of MAb Fc altogether to determine whether complement activation and subsequent uptake of the IC via complement receptors or engagement of inhibitory FcRs might be involved in our system. Therefore, immunization experiments were performed using IC containing F(ab)2 fragments of MAbs 6-11A and 5-5D in place of intact MAbs. Sera from mice immunized with the high and low concentrations of 6-11A F(ab)2 IC and the low concentration of 5-5D F(ab)2 IC demonstrated an increased ability to inhibit bacterial adherence inhibition by the BIAcore SPR assay (Figure 5A). The sera from the mice receiving both concentrations of 6-11A F(ab)2 IC and the low concentration of 5-5D F(ab)2 IC exhibited a statistically significant increase in competition against biotin-labeled MAb 1-6F compared to the serum of mice immunized with S. mutans alone (Figure 5B). When the IgG subclass reactivity with polypeptide NR21 was evaluated in IC compared to S. mutans-immunized mice significant increases (P<0.05) in IgG1 were detected in the sera of the 6-11A high F(ab)2 concentration and 5-5D low F(ab)2 concentration groups, in IgG2a in the 6-11A high and low F(ab)2 concentration and 5-5D low F(ab)2 concentration groups; and in IgG2b in the 6-11A high and low F(ab)2 concentration groups (Figure 5C). Collectively these data, in concert with the results in Fcer1g transgenic mice, indicate that beneficial immunomodulatory effects of anti-P1 MAbs are not dependent on Fc-mediated effector functions although that does not entirely rule out that Fc-dependent influences may not also occur simultaneously. The exclusion of an absolute requirement of MAb Fc in promotion of a desirable response is consistent with previous data which demonstrated that the beneficial MAbs were not opsonic for uptake by a macrophage cell line and that an ability to activate complement did not parallel with beneficial compared to detrimental immunomodulatory characteristics (32).

Figure 5.

Evaluation of the role MAb Fc on beneficial immunomodulation. (A) BIAcore SPR analysis of S. mutans adherence to SAG in the presence of sera from BALB/c mice immunized with ICs containing high (saturating) or low (0.1× sub-saturating) concentrations of MAb 6-11A F(ab)2 or MAb 5-5D F(ab)2 compared to mice immunized with S. mutans alone. (B) MAb 1-6F competition ELISA. The percent competition by sera from mice immunized with S. mutans alone (white bars), or IC containing MAb 6-11A F(ab)2 or MAb 5-5D F(ab)2 at the high saturating (black bars) or low 0.1× sub-saturating concentration (grey bars) is indicated. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM and statistical significance compared to serum from S. mutans only immunized mice is indicated by P values (C) Quantitative anti-NR21 IgG subclass ELISA. The levels of NR21-specific IgG1, IgG2a, and IgG2b subclass antibodies measured in the sera collected from mice immunized with S. mutans alone (diamonds), or with IC containing MAb 6-11A F(ab)2 or MAb 5-5D F(ab)2 at the high saturating (squares) or low 0.1× sub-saturating concentration (triangles) is indicated. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM. Data are representative of at least three independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using graph pad prism 4.0 and analysis included one-way anova.

Re-evaluation of the immunomodulatory properties of MAb 4-10A and exposure of the 1-6F epitope

A common denominator of the three known beneficial immunomodulatory MAbs 6-11A, 3-10E, and 5-5D is shared structural features of P1 that contribute to their complex conformationally-dependent epitopes. All three of their cognate epitopes require an interaction of the discontinuous A- and P-regions of P1, with pre-A-region sequence contributing to the epitopes of 6-11A, 5-5D and 3-10E and post-P-region sequence also contributing to the epitope recognized by 3-10E (35–38). MAb 4-10A is similar to these MAbs in its requirement for the A-region-P-region interaction; however, it had previously been found to be neutral in its ability to promote the desirable bacterial adherence inhibiting response (34, 45). Because prozone-like effects of exogenously administered antibodies have been observed in ours and other systems and desirable results may require lower rather than higher amounts of antibody (23, 34, 46), 4-10A was re-evaluated in murine immunization experiments over a broader concentration range within the IC.

BALB/c mice were immunized with S. mutans only or S. mutans reacted with serial 2-fold dilutions of MAb 4-10A beginning at a 0.1× sub-saturating coating concentration and a pronounced prozone-like effect was observed (Figure 6A). When tested by BIAcore SPR assay the sera from mice immunized with S. mutans IC containing the intermediate concentrations of MAb were clearly able to interfere with bacterial adherence to SAG better than sera from mice that received S. mutans alone or mice that received IC containing the higher or lower concentrations of MAb (Figure 6A). Optimal effects of sera from mice immunized with IC containing intermediate concentrations of MAb were also observed in other experiments. These included an increased ability of sera collected as early as seven days post-primary immunization to compete for S. mutans binding with biotin-labeled MAb 1-6F (Figure 6B) and increased levels of anti-NR21 antibodies of all three IgG isotypes, with IgG1 and IgG2a being the most pronounced (Figure 6C).

Figure 6.

Re-evaluation of the immunomodulatory properties of MAb 4-10A. (A) BIAcore SPR analysis of S. mutans adherence to salivary agglutinin in the presence of sera collected from BALB/c mice immunized with S. mutans alone or with ICs containing MAb 4-10A at the indicated dilutions. For the sake of clarity the change in resonance units detected over the 60 second injection cycle rather than the complete sensograms are shown. (B) MAb 1-6F competition ELISA. Sera collected from mice 7 days after primary immunization with S. mutans alone or with ICs containing MAb 4-10A at the indicated dilutions were tested for their ability to inhibit binding of biotin-labeled 1-6F to S. mutans whole cells. Results are expressed as the mean percent inhibition ± SEM and statistical significance compared to serum from S. mutans only immunized mice is indicated by P values. (C) Quantitative anti-NR21 IgG subclass ELISA. The levels of NR21-specific IgG1, IgG2a, and IgG2b subclass antibodies were measured in the same sera described in panel B. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM and statistical significance compared to serum from S. mutans only immunized mice is indicated by P values. (D) MAb 4-10A enhancement of MAb 1-6F binding to S. mutans whole cells by ELISA. The percent increase or decrease in binding of biotin-labeled MAb 1-6F to S. mutans in the presence of MAb 4-10A added at the indicated dilution was calculated. Data are representative of three independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using graph pad prism 4.0 and analysis included one-way anova.

Although MAb 1-6F is the only anti-P1 MAb in our panel to react with the P1-derived NR21 polypeptide, this MAb is not strongly reactive with purified full-length P1 (38) suggesting that its epitope is partially masked within the context of the entire molecule (Figure 1D). Since all the sera from mice immunized with IC that contained beneficial MAbs, including 4-10A at intermediate concentrations, also contained increased levels of 1-6F-like antibodies, we hypothesized that a MAb-mediated alteration in P1’s immunogenicity in vivo would be reflected by a detectable change in exposure of the 1-6F epitope on S. mutans surface-localized P1 in vitro. To test that possibility a modification of the 1-6F competition ELISA assay was employed; however, rather than inhibition of binding of the biotin-labeled MAb to S. mutans whole cells the measured endpoint was enhancement of 1-6F reactivity. When serial two-fold dilutions of MAb 4-10A were reacted with S. mutans prior to addition of biotin-labeled 1-6F a greater than 100% increase in 1-6F (Figure 6D) binding was observed in the same 4-10A concentration range as that shown to promote the formation of 1-6F-like antibodies in the immunization experiments (compare Figure 6A).

Immunization with truncated P1 elicits antibodies better able to inhibit S. mutans adherence

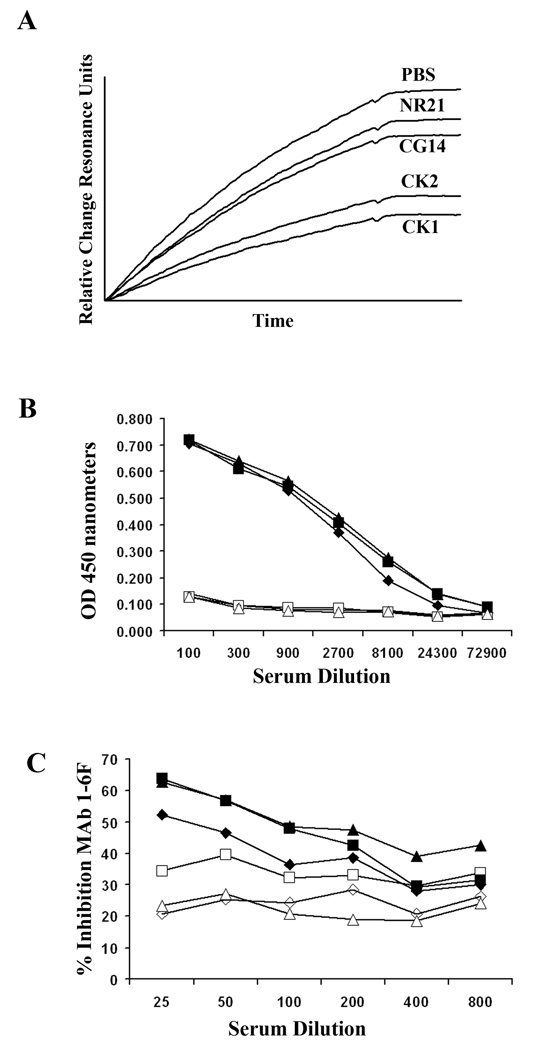

To confirm that structural alteration of P1 can result in an improvement in the functional activity of elicited antibodies, mice were immunized with full-length P1 compared to several truncated variants. These included polypeptides NR21, CK1 and CK2 (see Figure 1). NR21 achieves the 1-6F epitope but lacks the A- and P-regions and as stated above is not recognized by any other anti-P1 MAbs. CK1 and CK2 lack the post-P-region, and varying degrees of pre-A-region sequence, respectively. Pre-A region sequence encompassing amino acid residues 84–185 was shown previously to contribute to the epitopes recognized by the beneficial MAbs 6-11A and 5-5D (38). This segment is essential for formation of the 3-10E epitope (38) an interaction between the pre-A-region and post-P region (residues 964–1218) is required for achievement of native-like structure and recognition by MAb 3-10E (35). The binding of MAb 1-6F to CK1 and CK2 is greatly enhanced compared to the full-length recombinant P1 polypeptide CG14 (38) suggesting that the pre-A- and post-P-region interaction contributes to the conformation of P1 in which the 1-6F epitope is partially masked.

Compared to CG14, sera from mice that were immunized with CK1 or CK2 showed a substantial increase in their ability to inhibit adherence of S. mutans to immobilized SAG when evaluated by BIAcore assay (Figure 7A). The degree of bacterial adherence in the presence of serum from sham immunized buffer only mice is also shown. Despite the notable difference in functional activity, sera from the CK1 and CK2 groups of mice were similarly reactive to that from the CG14 group when tested against S. mutans whole cells by ELISA (Figure 7B). This implies that the functional difference in adherence inhibition stemmed from a change in antibody specificity. The ability of sera from the different groups to inhibit binding of biotin-labeled 1-6F to S. mutans whole cells by competition ELISA is shown in Figure 7C. Serum from mice immunized with NR21 was not inhibitory of bacterial adherence (Figure 7A), did not react with S. mutans whole cells (Figure 7B), and was not an efficient competitor of 1-6F binding to the bacterial cell surface (Figure 7C). This indicates that the NR21 polypeptide is not an effective immunogen, although it can serve as an appropriate antigen for detection of 1-6F-like antibodies in immunoassays. In addition to 1-6F, the CK1 and CK2 polypeptides are both recognized by two additional adherence-inhibiting anti-P1 MAbs, 4-9D and 4-10A. The 4-10A epitope is completely reconstituted by interaction of separate fragments corresponding to the A-and P-regions, whereas the 4-9D epitope cannot be reconstituted in trans and is destroyed when P1 is disrupted between amino acid residues 464 and 465 (38). Hence, optimal immunogenicity appears to represent a balance between preservation of sufficient conformational complexity to reconstitute relevant target epitopes, while disrupting the native structure such that immunodominance is shifted toward a more effective response.

Figure 7.

Evaluation of immunogenic properties of recombinant P1 polypeptides. (A) BIAcore SPR analysis of S. mutans adherence to salivary agglutinin. Sensograms show the binding of S. mutans to immobilized SAG in the presence of sera collected from sham-immunized (PBS) BALB/c mice compared to those immunized with GC14 (full-length recombinant P1) or with truncated polypeptides NR21, CK1 and CK2. (B) Sera collected from mice immunized with CG14 (filled diamonds), NR21 (open squares), CK1 (filled triangles), CK2 (filled squares), MBP alone (open diamonds), or acrylamide alone (open triangles) were tested for their total IgG reactivity against S. mutans whole cells by ELISA. (C) MAb 1-6F competition ELISA. The percent inhibition of biotin-labeled 1-6F to S. mutans whole cells by sera from mice immunized with CG14 (filled diamonds), NR21 (open squares), CK1 (filled triangles), CK2 (filled squares), MBP alone (open diamonds), or acrylamide alone (open triangles) are shown by line graph. The standard deviation between replicate samples was less than 5 percent in all cases.

Discussion

Even though antibody-mediated protection against dental caries has been documented, S. mutans is typical of chronic persistent pathogens and can survive in the presence of a detectable immune response. Immunomodulation by exogenously added MAb represents a method of improving the efficacy of an immune response by shifting the response towards more effective but potentially sub-dominant target epitopes. The overall goal of this study was to further define anti-P1 MAb-mediated changes in antibody specificity and isotype and to gain an understanding of the mechanism(s) by which these MAbs modulate and improve the efficacy of the resultant immune response when they are administered as part of an IC in a BALB/c host, a widely used model for studying immune responses against S. mutans antigens. We utilized whole S. mutans cells in our initial immunization experiments rather than purified P1 because we wished to evaluate the immunodominant response against P1 in its native form on the cell surface and learn how that response could be changed for the better. As a marker of biological function and activity against a known virulence attribute we measured the ability of elicited antibodies to interfere with P1 mediated adherence of S. mutans to the SAG receptor normally present within the human salivary pellicle.

The anti-P1 MAb 1-6F inhibits adherence of S. mutans to immobilized SAG and increased levels of 1-6F-like antibodies were consistently detected in the sera of animals immunized with IC containing beneficial immunomodulatory MAbs. In keeping with our previous results that demonstrated that adherence inhibition correlated with anti-S. mutans antibodies of the IgG2a and IgG2b isotypes (34), anti-1-6F-like antibodies of either or both of these subclasses were also increased in the sera from IC-immunized mice that demonstrated increased functional activity in the BIAcore SPR assay.

Broadly classified, the ways antibody are known to modulate the host immune response when it is bound to its specific Ag as part of an IC include Fc-dependent mechanisms such as increased uptake by antigen presenting cells via FcRs, engagement of stimulatory or inhibitory FcRs on antigen presenting cells (29, 31, 47–50), as well as Ab-mediated complement activation with subsequent uptake of Ag via complement receptors (29, 48, 51). Fc-independent mechanisms include Ab masking of dominant antigenic epitopes, exposure of cryptic epitopes revealed upon Ab binding, and/or changes in proteolysis which leads to changes in Ag presentation (49, 51–58). Results of the current study employing Fcer1g transgenic BALB/c mice demonstrated that beneficial immunomodulation by anti-P1 MAbs is independent of activating FcRs. Further experiments substantiated that the primary mechanism of beneficial immunomodulation by anti-P1 MAbs 6-11A and 5-5D did not require the Fc region to mediate their effects. These results corroborate other studies in our laboratory that showed that beneficial immunomodulatory properties of anti-P1 MAbs do not partition with their ability to promote opsonophagocytosis or to activate complement (32).

Previously an epitope scanning approach evaluating T cell and linear B cell epitopes revealed that the response to P1 varied depending on the MHC II haplotype of the murine host (59). The effects of beneficial MAbs correspond with a shared feature of their epitopes, i.e. a common structural requirement for the interaction of the discontinuous A- and P-regions of P1. If, as suggested by changes in the specificity of the subsequent immune response, these MAbs act in some way as to perturb P1 structure and expose other epitopes, one would predict the immunomodulatory effect to vary depending on the MHC II haplotype and genetic background of the host. An influence on P1 structure would be expected to lead to changes in antigen processing and presentation, the subset of stimulated T helper cells, and the ultimate B cell response. The stimulation of particular T cell subsets is remarkably dependent on minor alterations in an Ag (52). The current study tested and confirmed the importance of host genetic background in beneficial immunomodulation by anti-P1 MAbs.

The unifying property of anti-P1 MAbs that promote a desirable adherence inhibiting antibody response is a common intra-molecular interaction necessary for formation of their cognate epitopes implying that the mechanism responsible for their redirection of the immune response involves the nature of the Ag-Ab interaction itself. Interestingly, binding of the anti-Antigen I/II MAb Guy’s 13 reported to confer long term protection as part of a passive immunization approach in human clinical trials also requires an A/P-region interaction for formation of its cognate epitope (60–64). P1 binding by three of our four A/P-dependent MAbs (6-11A, 5-5D, and 3-10E) involves an additional contribution of pre-A region sequence (amino acids 84–190) and in-frame deletion of this region increases binding of the adherence inhibiting MAb 1-6F to P1 even though MAb 1-6F maps to the intervening region between the A- and P-regions (amino acids 465–679) (38). Hence it is tempting to speculate that binding of these immunomodulatory MAbs to P1 on the S. mutans cell surface has a similar effect on exposure of the 1-6F epitope. Collectively our data indicate that binding of beneficial immunomodulatory anti-P1 MAbs to S. mutans increases the antigenicity and immunogenicity of a different epitope than their own. The most convincing evidence that immunomodulation is linked to epitope exposure and a structural perturbation of P1 on the cell surface is the demonstration that MAb 4-10A increases the binding of biotin-labeled MAb 1-6F to S. mutans whole cells at the same dilutions shown to promote MAb 1-6F-like responses and adherence inhibition activity in the serum of IC-immunized mice. While the 1-6F epitope is not immunodominant in the absence of an uncomplexed beneficial MAb, it is detectable on S. mutans whole cells. Therefore, an increase in antibodies against this epitope would be expected to function to block adhesion of colonizing bacteria in the oral cavity.

Further confirmation that structural modification of P1 alters its immunogenicity such that a more desirable response can be achieved was obtained in immunization experiments utilizing the CK1 and CK2 derivatives of P1 that lack the post-P- and pre-A segments of the molecule. These regions were previously shown to contribute to P1’s native architecture on the cell surface (35). The comparable results obtained with the CK1 and CK2 constructs suggest that the pre-A-region residues 84–185 are not critical to elicit an adherence-inhibiting response in the context of these two polypeptides. Even though the relevant 1-6F epitope is achieved in polypeptide NR21, the disparity between the results of adherence inhibition, whole cell ELISA, and 1-6F competition experiments compared to CK1 and CK2 suggests that epitopes other than 1-6F may also be important targets of adherence inhibiting antibodies. In addition, the poor immunogenicity of NR21 compared to CK1 and CK2 may relate to a lack of helper T cell epitopes. When RANKPEP was used to predict P1 peptides that would interact with highest affinity with class II MHC molecules of BALB/c mice, NR21 contained a single peptide predicted to be displayed by I-Ad whereas, CK1 and CK2 contained 3/5 and 4/5 of the I-Ad predicted peptides and 3/5 and 4/5 of the I-Ed predicted peptides, respectively.

The current study provides new information regarding a strategy to manipulate the immune response toward the induction of anti-P1 antibodies with a more desirable characteristic, i.e. inhibition of S. mutans adherence to its known physiological receptor. In addition to a potential therapeutic modality, the insight gained regarding specific MAb-mediated changes in the elicited immune response suggest that immunization with immune complexes in an animal model can also be used as screening tool to learn the qualities of a more useful immune response. The approach of antibody-mediated immunomodulation either as a direct therapy or as a guide to immunogen re-engineering and achievement of an effective immune response may be broadly applicable to numerous pathogens beyond S. mutans for which vaccines are not yet available and that share the common characteristic of being able to persist in the face of a sub-optimal immune response.

Acknowledgements

We thank Arnold Bleiweis and Paula Crowley for scientific discussion and Paula Crowley for technical assistance.

This work was supported by the National Institute for Dental and Craniofacial Research grant DE13882 to L.J.B. and training grant T32-DE07200.

Footnotes

"This is an author-produced version of a manuscript accepted for publication in The Journal of Immunology (The JI). The American Association of Immunologists, Inc. (AAI), publisher of The JI, holds the copyright to this manuscript. This version of the manuscript has not yet been copyedited or subjected to editorial proofreading by The JI; hence, it may differ from the final version published in The JI (online and in print). AAI (The JI) is not liable for errors or omissions in this author-produced version of the manuscript or in any version derived from it by the U.S. National Institutes of Health or any other third party. The final, citable version of record can be found at www.jimmunol.org."

References

- 1.Hamada S, Slade HD. Biology, immunology, and cariogenicity of Streptococcus mutans. Microbiol Rev. 1980;44:331–384. doi: 10.1128/mr.44.2.331-384.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Michalek SM, Katz J, Childers NK. A vaccine against dental caries: an overview. BioDrugs. 2001;15:501–508. doi: 10.2165/00063030-200115080-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith DJ, Shoushtari B, Heschel RL, King WF, Taubman MA. Immunogenicity and protective immunity induced by synthetic peptides associated with a catalytic subdomain of mutans group streptococcal glucosyltransferase. Infect Immun. 1997;65:4424–4430. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.11.4424-4430.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith DJ, Taubman MA. Experimental immunization of rats with a Streptococcus mutans 59-kilodalton glucan-binding protein protects against dental caries. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3069–3073. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.8.3069-3073.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang P, Jespersgaard C, Lamberty-Mallory L, Katz J, Huang Y, Hajishengallis G, Michalek SM. Enhanced immunogenicity of a genetic chimeric protein consisting of two virulence antigens of Streptococcus mutans and protection against infection. Infect Immun. 2002;70:6779–6787. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.12.6779-6787.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Russell MW, Lehner T. Characterisation of antigens extracted from cells and culture fluids of Streptococcus mutans serotype c. Arch Oral Biol. 1978;23:7–15. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(78)90047-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Okahashi N, Sasakawa C, Yoshikawa M, Hamada S, Koga T. Molecular characterization of a surface protein antigen gene from serotype c Streptococcus mutans, implicated in dental caries. Mol Microbiol. 1989;3:673–678. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1989.tb00215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jenkinson HF, Demuth DR. Structure, function and immunogenicity of streptococcal antigen I/II polypeptides.PG - 183-90. Mol Microbiol. 1997;23 doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.2021577.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brady LJ, Piacentini DA, Crowley PJ, Oyston PC, Bleiweis AS. Differentiation of salivary agglutinin-mediated adherence and aggregation of mutans streptococci by use of monoclonal antibodies against the major surface adhesin P1. Infect Immun. 1992;60:1008–1017. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.3.1008-1017.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koga T, Yamashita Y, Nakano Y, Kawasaki M, Oho T, Yu H, Nakai M, Okahashi N. Surface proteins of Streptococcus mutans. Dev Biol Stand. 1995;85:363–369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee SF, Progulske-Fox A, Erdos GW, Piacentini DA, Ayakawa GY, Crowley PJ, Bleiweis AS. Construction and characterization of isogenic mutants of Streptococcus mutans deficient in major surface protein antigen P1 (I/II) Infect Immun. 1989;57:3306–3313. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.11.3306-3313.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Munro GH, Evans P, Todryk S, Buckett P, Kelly CG, Lehner T. A protein fragment of streptococcal cell surface antigen I/II which prevents adhesion of Streptococcus mutans. Infect Immun. 1993;61:4590–4598. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.11.4590-4598.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prakobphol A, Xu F, Hoang VM, Larsson T, Bergstrom J, Johansson I, Frangsmyr L, Holmskov U, Leffler H, Nilsson C, Boren T, Wright JR, Stromberg N, Fisher SJ. Salivary agglutinin, which binds Streptococcus mutans and Helicobacter pylori, is the lung scavenger receptor cysteine-rich protein gp-340. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:39860–39866. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006928200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hajishengallis G, Koga T, Russell MW. Affinity and specificity of the interactions between Streptococcus mutans antigen I/II and salivary components. J Dent Res. 1994;73:1493–1502. doi: 10.1177/00220345940730090301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith DJ, Mattos-Graner RO. Secretory immunity following mutans streptococcal infection or immunization. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2008;319:131–156. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-73900-5_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bratthall D, Serinirach R, Hamberg K, Widerstrom L. Immunoglobulin A reaction to oral streptococci in saliva of subjects with different combinations of caries and levels of mutans streptococci. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1997;12:212–218. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1997.tb00381.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Challacombe SJ, Bergmeier LA, Rees AS. Natural antibodies in man to a protein antigen from the bacterium Streptococcus mutans related to dental caries experience. Arch Oral Biol. 1984;29:179–184. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(84)90051-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hocini H, Iscaki S, Bouvet JP, Pillot J. Unexpectedly high levels of some presumably protective secretory immunoglobulin A antibodies to dental plaque bacteria in salivas of both caries-resistant and caries-susceptible subjects. Infect Immun. 1993;61:3597–3604. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.9.3597-3604.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kelly CG, Todryk S, Kendal HL, Munro GH, Lehner T. T-cell, adhesion, and B-cell epitopes of the cell surface Streptococcus mutans protein antigen I/II. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3649–3658. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.9.3649-3658.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lehtonen OP, Grahn EM, Stahlberg TH, Laitinen LA. Amount and avidity of salivary and serum antibodies against Streptococcus mutans in two groups of human subjects with different dental caries susceptibility. Infect Immun. 1984;43:308–313. doi: 10.1128/iai.43.1.308-313.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rose PT, Gregory RL, Gfell LE, Hughes CV. IgA antibodies to Streptococcus mutans in caries-resistant and -susceptible children. Pediatr Dent. 1994;16:272–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tenovuo J, Lehtonen OP, Aaltonen AS. Caries development in children in relation to the presence of mutans streptococci in dental plaque and of serum antibodies against whole cells and protein antigen I/II of Streptococcus mutans. Caries Res. 1990;24:59–64. doi: 10.1159/000261240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brady LJ, van Tilburg ML, Alford CE, McArthur WP. Monoclonal antibody-mediated modulation of the humoral immune response against mucosally applied Streptococcus mutans. Infect Immun. 2000;68:1796–1805. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.4.1796-1805.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heyman B, Wiersma EJ, Kinoshita T. In vivo inhibition of the antibody response by a complement receptor-specific monoclonal antibody. J Exp Med. 1990;172:665–668. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.2.665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Laissue J, Cottier H, Hess MW, Stoner RD. Early and enhanced germinal center formation and antibody responses in mice after primary stimulation with antigen-isologous antibody complexes as compared with antigen alone. J Immunol. 1971;107:822–831. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pincus CS, Nussenzweig V. Passive antibody may simultaneously suppress and stimulate antibody formation against different portions of a protein molecule. Nature. 1969;222:594–596. doi: 10.1038/222594a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yuan R, Casadevall A, Spira G, Scharff MD. Isotype switching from IgG3 to IgG1 converts a nonprotective murine antibody to Cryptococcus neoformans into a protective antibody. J Immunol. 1995;154:1810–1816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heyman B. The immune complex: possible ways of regulating the antibody response. Immunol Today. 1990;11:310–313. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(90)90126-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heyman B. Regulation of antibody responses via antibodies, complement, and Fc receptors. Annu Rev Immunol. 2000;18:709–737. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heyman B. Functions of antibodies in the regulation of B cell responses in vivo. Springer Semin Immunopathol. 2001;23:421–432. doi: 10.1007/s281-001-8168-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heyman B. Feedback regulation by IgG antibodies. Immunol Lett. 2003;88:157–161. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(03)00078-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Isoda R, Robinette RA, Pinder TL, McArthur WP, Brady LJ. Basis of beneficial immunomodulation by monoclonal antibodies against Streptococcus mutans adhesin P1. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2007;51:102–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2007.00279.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oli MW, McArthur WP, Brady LJ. A whole cell BIAcore assay to evaluate P1-mediated adherence of Streptococcus mutans to human salivary agglutinin and inhibition by specific antibodies. J Microbiol Methods. 2005 doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2005.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oli MW, Rhodin N, McArthur WP, Brady LJ. Redirecting the humoral immune response against Streptococcus mutans antigen P1 with monoclonal antibodies. Infect Immun. 2004;72:6951–6960. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.12.6951-6960.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Crowley PJ, Seifert TB, Isoda R, van Tilburg M, Oli MW, Robinette RA, McArthur WP, Bleiweis AS, Brady LJ. Requirements for surface expression and function of adhesin P1 from Streptococcus mutans. Infect Immun. 2008;76:2456–2468. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01315-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rhodin NR, Cutalo JM, Tomer KB, McArthur WP, Brady LJ. Characterization of the Streptococcus mutans P1 epitope recognized by immunomodulatory monoclonal antibody 6-11A. Infect Immun. 2004;72:4680–4688. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.8.4680-4688.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Seifert TB, Bleiweis AS, Brady LJ. Contribution of the alanine-rich region of Streptococcus mutans P1 to antigenicity, surface expression, and interaction with the proline-rich repeat domain. Infect Immun. 2004;72:4699–4706. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.8.4699-4706.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McArthur WP, Rhodin NR, Seifert TB, Oli MW, Robinette RA, Demuth DR, Brady LJ. Characterization of epitopes recognized by anti-Streptococcus mutans P1 monoclonal antibodies. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2007;50:342–353. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2007.00260.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brady LJ, Cvitkovitch DG, Geric CM, Addison MN, Joyce JC, Crowley PJ, Bleiweis AS. Deletion of the central proline-rich repeat domain results in altered antigenicity and lack of surface expression of the Streptococcus mutans P1 adhesin molecule. Infect Immun. 1998;66:4274–4282. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.9.4274-4282.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ayakawa GY, Boushell LW, Crowley PJ, Erdos GW, McArthur WP, Bleiweis AS. Isolation and characterization of monoclonal antibodies specific for antigen P1, a major surface protein of mutans streptococci. Infect Immun. 1987;55:2759–2767. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.11.2759-2767.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rundegren J, Arnold RR. Differentiation and interaction of secretory immunoglobulin A and a calcium-dependent parotid agglutinin for several bacterial strains. Infect Immun. 1987;55:288–292. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.2.288-292.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Petrushina I, Tran M, Sadzikava N, Ghochikyan A, Vasilevko V, Agadjanyan MG, Cribbs DH. Importance of IgG2c isotype in the immune response to beta-amyloid in amyloid precursor protein/transgenic mice. Neurosci Lett. 2003;338:5–8. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(02)01357-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rivera J, Casadevall A. Mouse Genetic Background Is a Major Determinant of Isotype-Related Differences for Antibody-Mediated Protective Efficacy against Cryptococcus neoformans. J Immunol. 2005;174:8017–8026. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.12.8017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nimmerjahn F, Ravetch JV. Divergent immunoglobulin g subclass activity through selective Fc receptor binding. Science. 2005;310:1510–1512. doi: 10.1126/science.1118948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sedlacek HH, Gronski P, Hofstaetter T, Kanzy EJ, Schorlemmer HU, Seiler FR. The biological properties of immunoglobulin G and its split products [F(ab')2 and Fab] Klin Wochenschr. 1983;61:723–736. doi: 10.1007/BF01497399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Taborda CP, Rivera J, Zaragoza O, Casadevall A. More is not necessarily better: prozone-like effects in passive immunization with IgG. J Immunol. 2003;170:3621–3630. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.7.3621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Getahun A, Dahlstrom J, Wernersson S, Heyman B. IgG2a-mediated enhancement of antibody and T cell responses and its relation to inhibitory and activating Fc gamma receptors. J Immunol. 2004;172:5269–5276. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.9.5269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lanzavecchia A. Receptor-mediated antigen uptake and its effect on antigen presentation to class II-restricted T lymphocytes. Annu Rev Immunol. 1990;8:773–793. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.08.040190.004013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Manca F, Fenoglio D, Li Pira G, Kunkl A, Celada F. Effect of antigen/antibody ratio on macrophage uptake, processing, and presentation to T cells of antigen complexed with polyclonal antibodies. J Exp Med. 1991;173:37–48. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.1.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wernersson S, Karlsson MC, Dahlstrom J, Mattsson R, Verbeek JS, Heyman B. IgG-mediated enhancement of antibody responses is low in Fc receptor gamma chain-deficient mice and increased in Fc gamma RII-deficient mice. J Immunol. 1999;163:618–622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Manca F. Interference of monoclonal antibodies with proteolysis of antigens in cellular and in acellular systems. Ann Ist Super Sanita. 1991;27:15–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Antoniou AN, Blackwood SL, Mazzeo D, Watts C. Control of antigen presentation by a single protease cleavage site. Immunity. 2000;12:391–398. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80191-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Antoniou AN, Watts C. Antibody modulation of antigen presentation: positive and negative effects on presentation of the tetanus toxin antigen via the murine B cell isoform of FcgammaRII. Eur J Immunol. 2002;32:530–540. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200202)32:2<530::AID-IMMU530>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Berzofsky JA. T-B reciprocity. An Ia-restricted epitope-specific circuit regulating T cell-B cell interaction and antibody specificity. Surv Immunol Res. 1983;2:223–229. doi: 10.1007/BF02918417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kunkl A, Klaus GG. The generation of memory cells. IV. Immunization with antigen-antibody complexes accelerates the development of B-memory cells, the formation of germinal centres and the maturation of antibody affinity in the secondary response. Immunology. 1981;43:371–378. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liu C, Gosselin EJ, Guyre PM. Fc gamma RII on human B cells can mediate enhanced antigen presentation. Cell Immunol. 1996;167:188–194. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1996.0026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Simitsek PD, Campbell DG, Lanzavecchia A, Fairweather N, Watts C. Modulation of antigen processing by bound antibodies can boost or suppress class II major histocompatibility complex presentation of different T cell determinants. J Exp Med. 1995;181:1957–1963. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.6.1957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Watts C, Antoniou A, Manoury B, Hewitt EW, McKay LM, Grayson L, Fairweather NF, Emsley P, Isaacs N, Simitsek PD. Modulation by epitope-specific antibodies of class II MHC-restricted presentation of the tetanus toxin antigen. Immunol Rev. 1998;164:11–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1998.tb01203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Takahashi I, Matsushita K, Nisizawa T, Okahashi N, Russell MW, Suzuki Y, Munekata E, Koga T. Genetic control of immune responses in mice to synthetic peptides of a Streptococcus mutans surface protein antigen. Infect Immun. 1992;60:623–629. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.2.623-629.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ma JK, Hunjan M, Smith R, Kelly C, Lehner T. An investigation into the mechanism of protection by local passive immunization with monoclonal antibodies against Streptococcus mutans. Infect Immun. 1990;58:3407–3414. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.10.3407-3414.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ma JK, Hunjan M, Smith R, Lehner T. Specificity of monoclonal antibodies in local passive immunization against Streptococcus mutans. Clin Exp Immunol. 1989;77:331–337. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.van Dolleweerd CJ, Chargelegue D, Ma JK. Characterization of the conformational epitope of Guy's 13, a monoclonal antibody that prevents Streptococcus mutans colonization in humans. Infect Immun. 2003;71:754–765. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.2.754-765.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ma JK, Lehner T, Stabila P, Fux CI, Hiatt A. Assembly of monoclonal antibodies with IgG1 and IgA heavy chain domains in transgenic tobacco plants. Eur J Immunol. 1994;24:131–138. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830240120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.van Dolleweerd CJ, Kelly CG, Chargelegue D, Ma JK. Peptide mapping of a novel discontinuous epitope of the major surface adhesin from Streptococcus mutans. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:22198–22203. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400820200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]