Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), a well described, common problem affecting school-aged children, has an estimated prevalence in Ontario of 7% to 10% of boys and 3% of girls in the age range of four to 11 years. There has been a documented trend to increased use of stimulant medications in the treatment of this disorder in the United States.

OBJECTIVE:

To assess the prevalence of stimulant medication therapy for ADHD in three southern Ontario school boards.

PATIENTS AND METHODS:

A cross-sectional epidemiological study was performed by distributing a survey to all parents of children in kindergarten through grade 6 in six to eight schools selected randomly in each of the three participating school boards. The completed questionnaires were collated, and the comparative data were analyzed using χ2.

RESULTS:

A total of 5100 surveys were distributed among the three school boards; 1465 (28.8%) questionnaires were returned completed. Within the three school boards – Hastings County Board of Education, Metropolitan Toronto Separate School Board and the East York Board of Education – the prevalence of ADHD for the age groups surveyed was 4.3%, 3.4% and 6.8%, respectively (average 4.7%), with a peak average of almost 9% by 12 years of age. The percentages of children with diagnosed ADHD who were on stimulant medication were 43%, 3% and 13%, respectively. The differences between the school boards were statistically significant (P<0.05). The male versus female prevalence of a diagnosis of ADHD was 7.1% versus 1.2%, 3.8% versus 3.3% and 10.1% versus 3.6%, respectively, with a combined school board average of 7.1% of males versus 2.9% of females. The average percentage of males versus females who were diagnosed with ADHD and who were on stimulant medication was found to be 27% versus 5%.

CONCLUSIONS:

The prevalence of ADHD was 4.7% in the study population. The overall percentage of children who were on stimulant medication was approximately 1%. Males were not only more likely to be diagnosed with ADHD but also more likely to be treated with stimulant medications if diagnosed. There was an increased prevalence of ADHD with older age, and the different school boards had significant differences in both the percentages of children who were diagnosed with ADHD and the percentages of children who were on medication, suggesting that individual school board policies or other factors may affect both the rate of diagnosis and the likelihood of stimulant drug treatment.

Keywords: Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, Stimulant treatment, Stimulant medications

Abstract

HISTORIQUE :

Le trouble d’hyperactivité avec déficit de l’attention (THDA), un problème bien décrit et courant qui touche les enfants d’âge scolaire, présente une prévalence évaluée entre 7 % et 10 % chez les garçons et à 3 % chez les filles de quatre à 11 ans en Ontario. Aux États-Unis, on a documenté une tendance accrue à utiliser des médicaments stimulants pour traiter ce trouble.

OBJECTIF :

Évaluer la prévalence du traitement à l’aide de médicaments stimulants contre le THDA dans trois conseils scolaires du sud de l’Ontario.

MÉTHODOLOGIE :

Une étude épidémiologique transversale a été exécutée par sondage auprès de tous les parents d’enfants de la maternelle à la sixième année dans six à huit écoles choisies au hasard parmi chacun des trois conseils scolaires participants. Les questionnaires remplis ont été colligés, et les données comparatives ont été analysées au moyen de χ2.

RÉSULTATS :

Au total, 5 100 sondages ont été distribués dans les trois conseils scolaires; 1 465 (28,8 %) ont été renvoyés remplis. Dans les trois conseils scolaires, soit le Hastings County Board of Education, le Metropolitan Toronto Separate School Board et le East York Board of Education, la prévalence de THDA au sein des groupes d’âge sondés était de 4,3 %, 3,4 % et 6,8 %, respectivement (moyenne de 4,7 %), la moyenne de crête s’établissant à près de 9 % à l’âge de 12 ans. Le pourcentage d’enfants au THDA diagnostiqué qui prenaient des médicaments stimulants était de 43 %, 3 % et 13 %, respectivement. Les différences entre les conseils scolaires étaient significatives du point de vue statistique (P<0,05). La prévalence de diagnostic de THDA entre les garçons et les filles était de 7,1 % par rapport à 1,2 %, de 3,8 % par rapport à 3,3% et de 10,1 % par rapport à 3,6 %, respectivement, la moyenne combinée des conseils scolaires correspondant à 7,1 % de garçons par rapport à 2,9 % de filles. Le pourcentage moyen de garçons par rapport aux filles qui avaient reçu un diagnostic de THDA et qui prenaient des médicaments stimulants était de 27 % par rapport à 5 % de filles.

CONCLUSIONS :

La prévalence de THDA était de 4,7 % dans la population à l’étude. Le pourcentage global d’enfants qui prenaient des médicaments stimulants était de 1 % environ. Les garçons étaient non seulement plus susceptibles de recevoir un diagnostic de THDA, mais également de prendre des médicaments stimulants après un tel diagnostic. La prévalence de THDA était plus élevée chez les enfants plus âgés, et les divers conseils scolaires présentaient des différences marquées tant pour ce qui est du pourcentage d’enfants ayant reçu un diagnostic de THDA que pour celui d’enfants qui prenaient des médicaments, ce qui laisse supposer que les politiques de chaque conseil scolaire ou que d’autres facteurs influencent peut-être à la fois le taux de diagnostic et la vraisemblance d’utilisation à l’aide de médicaments stimulants.

Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) has been described as a common problem in school-aged children. A 1987 epidemiological study in Ontario found a prevalence of 7.0% to 10.1% in boys and 3% in girls aged four to 11 years (1,2). The diagnosis of ‘attention deficit disorder’ has undergone many changes over the years, from having a focus on a degree of neurological dysfunction to an emphasis on behavioural diagnostic criteria (3). ADHD is defined in the Diagnostic & Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) (4) as a chronic behavioural disorder.

There are many therapeutic approaches to the management of children with ADHD, but the mainstay of treatment appears to be stimulant medication (5–7). The most widely used drugs have been methylphenidate (Ritalin), pemoline (Cylert, Abbott Laboratories Limited, Saint Laurent, Quebec) and dextroamphetamine sulphate (Dexedrine, SmithKilne Beecham, Oakville, Ontario) (3). These drugs have been shown to offer an effective diminution of the behavioural problems and at least temporary improvement of school performance (8,9).

Significant controversy remains over the long term benefit of stimulant medications (3). Reviews by Wolraich (10) and Barkley (11) found little evidence for the long term efficacy of stimulant medications. Some studies suggest that a treatment program combining stimulants with other modalities may improve outcomes (12). There have also been other concerns raised with regard to stimulant medication treatment in ADHD. First, there has been a trend to increased use of this medication (5,13). This trend was first documented by an American study performed in Baltimore from 1971 to 1987 (13). It concluded that the number of children with ADHD being treated with medication doubled every four to seven years. In the final year, 5.96% of elementary-aged public school children were on stimulant medication in the area studied (13). Second, there have been concerns brought forth about the criteria used to diagnose ADHD (6,14,15). The use of the DSM-IV criteria to define ADHD has not been universally accepted (14). There are also issues regarding side effects and the possibility that these medications may mask other problems (16,17). The exact number of children in Ontario diagnosed with attention deficit disorder and treated with stimulant medicaton is not known.

In view of these concerns, the Child Development Clinic at The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Ontario performed an epidemiological study to determine the prevalence of ADHD and its treatment with stimulants by way of a survey developed by the Child Development Clinic at the hospital (18). The survey was distributed to families by way of the schools involved in the study and subsequently mailed back to the clinic.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

This cross-sectional epidemiological study was conducted with the cooperation of three Southern Ontario boards: the Hastings County Board of Education (HCBE), a predominantly rural, publicly funded, nonsecular school board; the Metropolitan Toronto Separate School Board (MSSB), an urban Catholic but publicly funded board, and the East York Board of Education (EYBE), an urban, publicly funded, nonsecular board.

Six to eight schools were surveyed in each school board, and the schools were randomly selected by using a random numbers table. The questionnaire developed by the authors’ research group was sent to all parents of children in kindergarten through grade six at the selected schools. The questionnaire was used to establish whether the child had already been diagnosed with ADHD and which medical treatments were being used to treat the condition. The questionnaires were distributed by teachers to all students in the grades specified, and a second distribution was carried out to improve the response rate. The questionnaires were to be completed by parents and mailed directly back to The Hospital for Sick Children in self-addressed, prestamped envelopes.

An average of 1700 surveys were sent to each board of education (HCBE n=1754, MSSB n=1649 and EYBE n=1697). The questionnaires were numerically coded for each school board and school, but were otherwise anonymous. Data were collated and comparative data were analyzed by the χ2 test with descriptive data given as means and probabilities.

RESULTS

The response rate for surveys completed and returned were 27.6% for HCBE, 31.7% for the MSSB and 27.0% for the EYBE (overall response rate 28.8%). Data from the three boards regarding the total number of replies, age distribution and sex distribution of respondents are given in Tables 1, 2 and 3.

TABLE 1:

Number and distribution by school board of surveys about attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder collected

| School board | Distribution | Responses | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Positive diagnosis | ||||

| Schools | Surveys | Medication | No medication | ||

| Hastings Board of Education (public, rural) | 6 | 1754 | 484 | 9 | 12 |

| East York Board of Education (public, urban) | 6 | 1697 | 459 | 4 | 27 |

| Metropolitan Toronto Separate School Board (Catholic, urban) | 8 | 1649 | 522 | 1 | 17 |

TABLE 2:

Age distribution of replies by school boards surveyed regarding information on attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder

| School board | Age distribution (years) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | |

| Hastings Board of Education (484 replies) | 8 | 70 | 78 | 74 | 79 | 75 | 59 | 40 | 1 | – |

| East York Board of Education (459 replies) | 7 | 33 | 78 | 58 | 66 | 73 | 81 | 52 | 9 | 2 |

| Metropolitan Toronto Separate School Board (522 replies) | – | 49 | 87 | 74 | 84 | 62 | 72 | 71 | 23 | – |

| Total | 15 | 152 | 243 | 206 | 229 | 210 | 212 | 163 | 33 | 2 |

TABLE 3:

Sex distribution of replies by school boards surveyed regarding information on attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder

| School board | Sex distribution | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Not indicated | |

| Hastings Board of Education (public, rural) | 256 | 228 | – |

| East York Board of Education (public, urban) | 253 | 205 | 1 |

| Metropolitan Toronto Separate School Board (Catholic, urban) | 274 | 247 | 1 |

| Total | 783 | 680 | 2* |

None of the students were on medication or had the diagnosis of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder

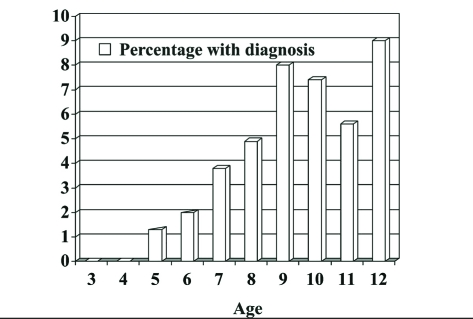

In the group of respondents, the percentages of children with diagnosed ADHD were 4.3% for the HCBE, 3.3% for the MSSB and 6.8% for the EYBE (average 4.8%) (Table 4). These differences were statistically significant among the three school boards (P=0.045). Of male respondents, ADHD had been diagnosed in 7.1%, 3.8% and 10.1% of the male children, respectively (average 7.1%), again a statistically significant difference among the boards (P=0.016). The percentages of females with the diagnosis of ADHD were 1.2%, 3.3% and 3.6% respectively, (average 2.9%), with no significant difference found among the three boards. The percentage of all children across the different boards with a diagnosis of ADHD increased with age, with a peak of 9% by 12 years of age (Figure 1).

TABLE 4:

Prevalence of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and stimulant medicaton treatment by school board

| Children | HCBE (rural) (%) | SMSSB (Catholic) (%) | EYSB (%) | Total (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| With diagnosis of ADHD | 4.3 (2.5–6.1) | 3.3 (1.7–4.8) | 6.8 (4.5–9.1) | 4.8* |

| Male with diagnosis | 7.1 | 3.8 | 10.1 | 7.1 |

| Female with diagnosis | 1.2 | 3.3 | 3.6 | 2.9 |

| On medication | 1.9 (0.7–3.1) | 0.19 (0–0.56) | 0.8 (0–1.7) | 1* |

| With diagnosis on medication | 43 | 3 | 13 | 20 |

| Male with diagnosis on medication | 53 | 0 | 19 | 27 |

| Female with diagnosis on medication | 0 | 12.5 | 0 | 5 |

Figures in brackets are 95% CIs.

Significant difference between school boards (P<0.05). HCBE Hastings Board of Education (public, rural); SMSSB Metro Separate School Board (Catholic); EYSB East York Board of Education (public, urban)

Figure 1).

Prevalence of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder versus age

The number of children on stimulant medications was also shown to be statistically different among the various school boards, with Hastings County averaging 1.9% of all respondents (43% of all children diagnosed with ADHD), the MSSB averaging 0.19% (3% of all children diagnosed with ADHD) and the EYBE averaging 0.8% (13% of all children diagnosed with ADHD) (P=0.02). The average number of children on stimulant medications across the school boards was 1% of all respondents.

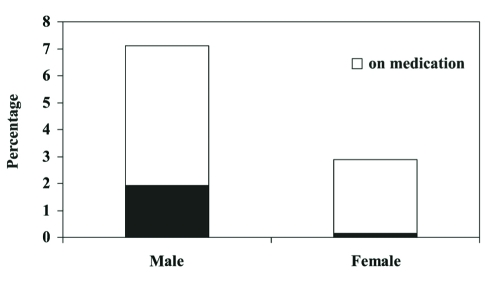

Overall, 27% of all males with diagnosed ADHD and 5% of all ADHD females were on stimulant medications (Figure 2). Fifty-three per cent of males with ADHD were on medications in the HCBE, 0% in the MSSB and 19% in the EYBE (P=0.0032). There was no statistical difference among the boards regarding females with ADHD on medication.

Figure 2).

Proportion of children on stimulant medication

The total average percentage of males versus females diagnosed with ADHD was studied, and a significantly higher percentage of males with the diagnosis was found (P=0.0003).

DISCUSSION

With our study, we set out to examine the prevalence of both ADHD and the use of stimulant medications in its treatment in three representative school boards from southern Ontario. The overall prevalence of ADHD was 4.7% for primary school-aged children, with 7.1% of males and 2.9% of females being diagnosed with ADHD. Although we do acknowledge the possibility of return bias inherent in this type of study, our findings are consistent with a previously estimated Ontario prevalence of 7% to 10% of boys and 3% of girls (1,2). From the time between the 1987 Ontario epidemiological study and the present study, there does not appear to have been an increase in the prevalence, thus differing from the trends documented in the United States (5,13). An increasing incidence of ADHD with age was seen in this study and would be expected because more children with ADHD are recognized the further that they progress through school.

The overall prevalence of stimulant medication use for the age group studied was approximately 1%. While this is consistent with the 1971 Baltimore County stimulant medication prevalence quoted in the study by Safer and Krager (13), the follow-up study completed by the same group in 1987 revealed the prevalence of 5.6%, which is a very significant growth in medication use in an elementary school population. Our data also supported previously documented male and female differences (5). Males were not only more than twice as likely to be diagnosed with ADHD, but were also much more likely to be treated with stimulant medications after the diagnosis was made than females.

There were also significant differences noted between school boards with regard to the percentage of diagnosed children with ADHD and the number of children on stimulant therapy. In general, the public boards had both higher rates of diagnosed children (HCBE 4.3% and EYBE 6.8% versus MSSB 3.3%) and higher percentages of children with ADHD on medication (HCBE 43% and EYBE 13% versus MSSB 3%). However, there was no statistically significant difference between the urban and rural school boards.

The differences in the percentage of children diagnosed with ADHD and stimulant medication use in ADHD may be related to variations in the school board populations, differences in board policies for the identification and management of children with school problems, or diagnostic and therapeutic biases of the physicians serving the specific communities. These issues, and the long term academic and behavioural benefits of stimulant medications require further investigation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Offord DR, Boyle MH, Szatmari P, et al. Ontario Child Health Study. II. Six-month prevalence of disorder and rates of service utilization. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1987;44:832–6. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800210084013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boyle MH, Offord DR, Hofmann HG, et al. Ontario Child Health Study. I. Methodology. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1987;44:826–31. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800210078012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stevenson RP, Wolraich ML. Stimulant medication therapy in the treatment of children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1989;36:1183–97. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(16)36764-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Psychiatric Association Staff . Diagnostic & Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV. Washington: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. pp. 78–85. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Safer DJ, Krager JM. Trends in medication treatment of hyperactive school children. Results of six biannual surveys. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 1983;22:500–4. doi: 10.1177/000992288302200707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Copeland L, Wolraich M, Lindgren S, Milich R, Woolson R. Pediatricians’ reported practices in the assessment and treatment of attention deficit disorders. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1987;8:191–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wolraich ML, Lindgren S, Stromquist A, Milich R, Davis C, Watson D. Stimulant medication use by primary care physicians in the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics. 1990;86:95–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pelham WE, Bender ME, Caddell J, Booth S, Moorer SH. Methylphenidate and children with attention deficit disorder. Dose effects on classroom academic and social behavior. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1985;42:948–52. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1985.01790330028003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Safer D, Krager JM. Hyperactivity and inattentiveness. School assessment of stimulant treatment. Clin Pediatr. 1989;28:216–21. doi: 10.1177/000992288902800504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wolraich M. Stimulant drug therapy in hyperactive children: research and clinical implications. Pediatrics. 1977;60:512–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barkley RA. A review of stimulant drug research with hyperactive children. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1977;18:137–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1977.tb00425.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hechtman L. Adolescent outcome of hyperactive children treated with stimulants in childhood: a review. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1985;2:178–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Safer DJ, Krager JM. A survey of medication treatment for hyperactive/inattentive students. JAMA. 1988;260:2256–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davy T, Rodgers CL. Stimulant medication and short attention span: a clinical approach. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1989;10:313–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Phillips S. The use of stimulant medication with children. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1989;10:319–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Golden GS. Gilles de la Tourette’s Syndrome following methylphenidate administration. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1974;16:76–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1974.tb02715.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barkley RA, McMurray MB, Edelbrock CS, Robbins K. Side effects of methylphenidate in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a systemic, placebo-controlled evaluation. Pediatrics. 1990;86:184–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Community surveys of the problems of childhood psychiatric disorders: a review. Child Dev. 1983;54:531–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]