Abstract

AIMS

The international childhood obesity epidemic has driven increased use of unlicensed antiobesity drugs, whose efficacy and safety are poorly studied in children and adolescents. We investigated the use of unlicensed antiobesity drugs (orlistat, sibutramine and rimonabant) in children and adolescents (0–18 years) in the UK.

METHODS

Population-based prescribing data from the UK General Practice Research Database between 1 January 1999 and 31 December 2006.

RESULTS

A total of 452 subjects received 1334 prescriptions during the study period. The annual prevalence of antiobesity drug prescriptions rose significantly from 0.006 per 1000 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.0007, 0.0113] in 1999 to 0.091 per 1000 (95% CI 0.07, 0.11) in 2006, a 15-fold increase, with similar increases seen in both genders. The majority of prescriptions were made to those ≥14 years old, although 25 prescriptions were made for children <12 years old. Orlistat accounted for 78.4% of all prescriptions; only one patient was prescribed rimonabant. However, approximately 45% of the patients ceased orlistat and 25% ceased sibutramine after only 1 month. The estimated mean treatment durations for orlistat and sibutramine were 3 and 4 months, respectively.

CONCLUSIONS

Prescribing of unlicensed antiobesity drugs in children and adolescents has dramatically increased in the past 8 years. The majority are rapidly discontinued before patients can see weight benefit, suggesting they are poorly tolerated or poorly efficacious when used in the general population. Further research into the effectiveness and safety of antiobesity drugs in clinical populations of children and adolescents is needed.

Keywords: antiobesity drug, children and adolescents, epidemiology, general practice, obesity

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ABOUT THIS SUBJECT

The antiobesity drugs sibutramine and orlistat are not licensed for use in children and adolescents in the UK or USA.

Clinical trials suggest antiobesity drugs are effective and well-tolerated in obese adolescents.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

Prescribing of unlicensed antiobesity drugs in children and adolescents has increased significantly in the past 8 years.

Most prescribed antiobesity drugs in children and adolescents are rapidly discontinued before patients can see clinical benefit, suggesting they are poorly tolerated or poorly efficacious.

Introduction

The epidemic of child and adolescent obesity in the UK and internationally is well described, with the prevalence of childhood obesity in the UK more than tripling since the 1980s [1]. Strong evidence of the tracking of both obesity and its cardiovascular comorbidities into adulthood [2, 3] has focused attention on intervention in childhood. Whereas attention has appropriately focused upon primary and secondary prevention strategies [1, 4], the management of those children and young people already obese has been relatively neglected.

Those who are already obese currently make up 7–10% of the child and adolescent population (<20 years old) using the conservative International Obesity Taskforce definition, proportions predicted by the Foresight modelling project to rise to approximately 14% by 2025 [5]. The proportion of this population that require or should receive treatment, whether reduction in overweight or treatment of obesity comorbidities, remains unclear. However, approximately 2–3% of older children and adolescents in urban areas such as inner London have a body mass index (BMI) ≥3.5 standard deviation (SD) above the mean [6], equivalent to the World Health Organization category of morbid obesity (BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2). Furthermore, approximately one-third of obese adolescents have significant obesity-related morbidity [7, 8].

The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) published guidance on managing obesity in childhood and adolescence in 2006 [9], identifying lifestyle modification as the initial management strategy, but also identifying antiobesity drug therapy and bariatric surgery as appropriate for the management of older children and adolescents in certain circumstances.

To date, there are two medications approved for obesity treatment in adults in the UK: the gastric and pancreatic lipase inhibitor orlistat (licensed for adults in 1998), and the serotonin and noradrenergic reuptake inhibitor sibutramine (licensed for adults in 2001). The selective cannabinoid CB1 receptor antagonist rimonabant was licensed in 2006 but withdrawn in 2008. Estimates suggested that in 2005, the drug supply costs of orlistat and sibutramine in England were £38.2 million [10]. In the USA, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved sibutramine for use in patients aged ≥16 years and orlistat for patients aged ≥12 years [11]. However, in the UK they are still not licensed for children. Based upon a very small number of clinical trials in children and adolescents, the recent NICE guidelines suggest that orlistat and sibutramine should be considered as useful adjuncts to lifestyle modification in adolescents ≥12 years old with physical comorbidities, and that use at <12 years old be reserved for those with life-threatening comorbidities [9].

However, there are no published data on the use of antiobesity drugs in children and adolescents in the UK, with no data concerning acceptability, effectiveness or duration of treatment in clinical practice. National primary care databases provide useful sources of paediatric prescribing data in the UK [12, 13]. Although NICE guidance recommends that antiobesity drugs for children and adolescents be initiated from secondary care in the UK [9], routine practice is for general practitioners (GPs) to prescribe after recommendation from paediatricians. We therefore used the General Practice Research Database (GPRD) to undertake an investigation of the prevalence of antiobesity drug prescribing and treatment duration among children and adolescents aged 0–18 years between 1999 and 2006.

Methods

The GPRD contains anonymized patient records from general practices in the UK, covering approximately 5% of the UK population [14]. The database is broadly representative of the UK population [15] and comprises anonymized records from approximately 8 million people from 1987 onwards, totalling about 30 million person-years of observation. Data held include subject demographic and clinical details including data on drug prescriptions and comorbid conditions. The quality of the GPRD data has been validated in a number of studies, the completeness of medical recording is reported to be high [14], and the GPRD has been used to investigate paediatric prescribing issues [12, 13].

Our study population was defined as all children and adolescents aged 0–18 years inclusive at the time of data collection, registered with a general practitioner who contributed data to the GPRD. From these we identified all subjects who had received at least one prescription for an antiobesity drug (orlistat, sibutramine or rimonabant) in the study period between 1 January 1999 and 31 December 2006. We calculated age- and sex-specific annual prevalence of overall and each antiobesity drug use. Prevalence was defined as the number of subjects with at least one antiobesity drug prescription during the year of investigation divided by the total number of patient-years in the same year stratified by age, and was calculated using the Poisson distribution with a 95% confidence interval (CI). The χ2 test (Cochran–Armitage test for trend) was used to examine yearly trends. We also obtained data on obesity-related comorbid diagnoses available in the database on subjects prescribed antiobesity drugs; given the range of conditions potentially comorbid with obesity, we a priori restricted our search to common diagnoses such as hypertension, dyslipidaemia, insulin resistance syndrome (metabolic syndrome), non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and depression.

The duration of antiobesity drug treatment was analysed using Kaplan–Meier survival analysis. Treatment was considered as stopped if there were no further prescriptions issued within 90 consecutive days (3 months) after the date of the last prescription. Subjects were censored either if the end of the study period was within <90 consecutive days after their last prescription or if they left the practice without stopping treatment. Log rank test was applied to compare duration of treatment between orlistat and sibutramine. The analyses were conducted using Stata version 9.1 (Statistical Software, Release 9.1; College Station, TX, USA).

The study protocol was approved by the GPRD Independent Scientific Advisory Committee.

Results

A total of 452 children and adolescents received 1334 prescriptions for antiobesity drugs during the study period. As there was only one prescription for rimonabant (in a patient aged 18 years in 2006), further analyses refer only to orlistat and sibutramine. Orlistat made up 78.4% (n= 1045) of all prescriptions.

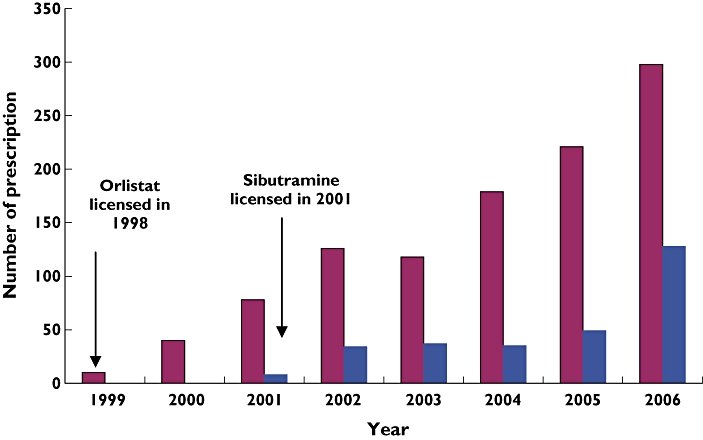

The great majority of prescriptions were issued to female patients (82.3%; n= 372). The mean age for first prescription was 17.0 years [SD 1.33; range 10–18 years; for women, mean 17.1 years (SD 1.27); for men, mean 16.7 years (SD 1.53)]. The median number of antiobesity drug prescriptions per subject was 2.0 (interquartile range 3.0); however, 40.5% (n= 183) received only one prescription. Figure 1 shows numbers of prescriptions by calendar year. The use of both orlistat and sibutramine increased rapidly after each drug was introduced into the UK. From 1999 to 2006, orlistat prescriptions rose from 10 to 282, a 28-fold increase; sibutramine prescriptions rose 16-fold from 8 to 128 between 2001 and 2006.

Figure 1.

Distribution of antiobesity prescriptions in the UK general practice, 1999–2006. Orlistat ( ); Sibutramine (

); Sibutramine ( )

)

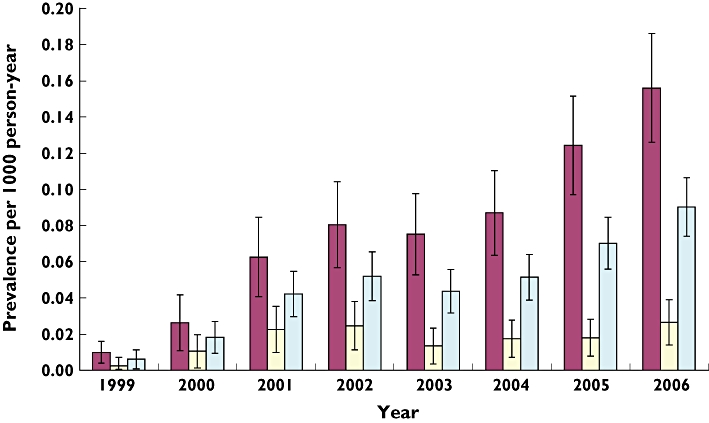

Figure 2 shows the prevalence of total antiobesity drug prescriptions by calendar year for each gender. Overall use increased 15-fold from 0.006 per 1000 person-years (95% CI 0.0007, 0.0113) in 1999 to 0.091 (0.07, 0.11) in 2006 (P < 0.0001). Similar increases were seen in both genders over the study period, increasing in girls from 0.009 (0.0001, 0.019) to 0.156 (0.126, 0.186) (P < 0.0001), and in boys from 0.002 (0.0019, 0.004) to 0.027 (0.012, 0.04) (P= 0.02).

Figure 2.

Prevalence of antiobesity drug prescribing by gender and year (with 95% CI), 1999–2006. girls ( ); boys (

); boys ( ); overall (

); overall ( )

)

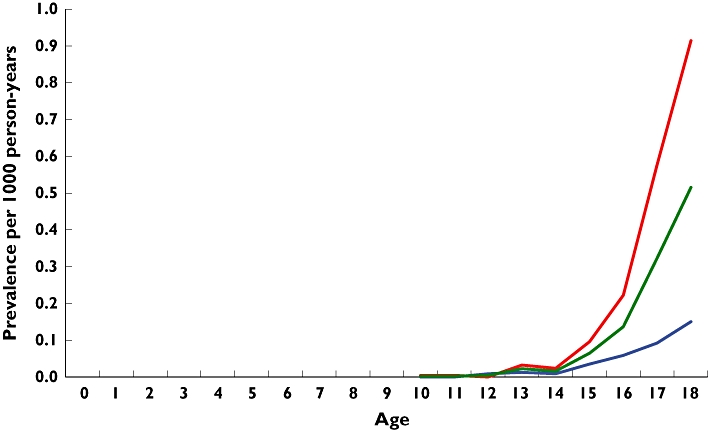

Figure 3 shows trends by age. No antiobesity drugs were prescribed to children <10 years old, although 25 prescriptions were issued to those <12 years old. Prescribing dramatically increased from age 14 years onwards.

Figure 3.

Age-specific prevalence of antiobesity drug prescribing, 1999–2006. girls ( ); boys (

); boys ( ); overall (

); overall ( )

)

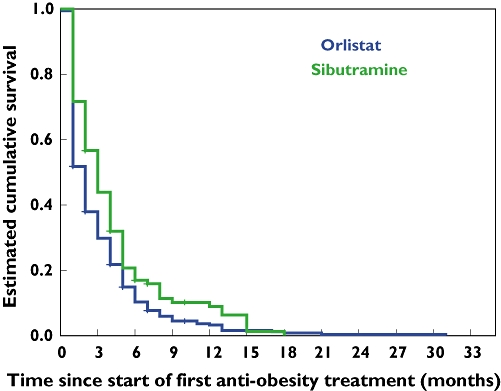

Figure 4 shows Kaplan–Meier survival curves for treatment duration for orlistat and sibutramine. The mean duration of orlistat use was significantly shorter (3.0 months; 95% CI 2.72, 3.47) compared with sibutramine (4.2 months; 95% CI 3.4, 5.0) (P= 0.003). Note that 45% of orlistat prescriptions were discontinued within the first month, with approximately 10% remaining on the drug after 6 months. For sibutramine, approximately 25% of prescriptions were discontinued within the first month, with <20% remaining on the drug at 6 months.

Figure 4.

Kaplan–Meier curves for children and adolescents who received antiobesity drug treatment.

There were 39 subjects who were prescribed both orlistat and sibutramine in our study; 34 subjects initially used orlistat and subsequently switched to sibutramine, and five subjects initially received sibutramine and then switched to orlistat. Data on reasons for changing between drugs were not available.

Table 1 shows obesity-related comorbid diagnoses in those prescribed antiobesity drugs. Note that all patients with a diagnosis of diabetes were also receiving antidiabetic drug treatment (either insulin or oral hypoglycaemic drugs).

Table 1.

Obesity-related comorbidity within population treated with antiobesity drugs

| Comorbidity diagnosis | % (n) |

|---|---|

| Diabetes mellitus | 4.9 (22) |

| Hypertension | 2.2 (10) |

| Depression | 28.5 (129) |

| Polycystic ovarian syndrome | 7.5 (28/372 women) |

Discussion

Prescribing of antiobesity drugs in children and adolescents while off-licence has increased dramatically over the last 8 years. Our 2006 data suggest that approximately 0.1 per 1000 of those aged ≤18 years are currently prescribed antiobesity drugs. Generalized across the UK population of 13 928 000 persons aged ≤18 years, this would suggest that approximately 1300 young people are prescribed off-licence antiobesity drugs annually. However, persistence with these drugs past the first month is strikingly poor, and only 25% of those prescribed orlistat and 35% of those prescribed sibutramine remained on the drug for longer than the 3 months generally regarded as an adequate time to ascertain whether significant weight loss has occurred.

These data suggest antiobesity drug prescribing is an emerging paediatric pharmacological risk issue. We document a rapid increase in prescribing for children and adolescents of unlicensed drugs, which are in most cases rapidly discontinued before patients can reasonably expect to see clinical benefit. Furthermore, this pattern of drug use is likely to be significantly wasteful of resources, as antiobesity medications are relatively expensive [10]. Although orlistat and sibutramine have shown significant but limited benefits for weight reduction and have reported good tolerability in a small number of randomized placebo-controlled trials, evidence for their effectiveness in large populations of young people is largely lacking [16]. NICE and FDA guidelines on the use of sibutramine and orlistat have been based upon very limited effectiveness data. Further research into effective and safe use of antiobesity drugs in children and adolescents outside of efficacy trials is needed. Investigation of the reasons for discontinuation of antiobesity drugs may allow the development of support strategies that minimize side-effects and maximize drug continuation when used in the general population.

Strengths and limitations

We believe that this is the first published population-based study of antiobesity drug prescribing in children and adolescents. The National Health Service (NHS) in the UK provides universal coverage. The GPRD contains robust data on prescriptions in primary care, and given the universal nature of the NHS in the UK, our estimates of population prescribing prevalences are highly likely to be sound and generalizable in UK primary care.

However, several limitations need to be highlighted. First, the GPRD records prescriptions issued in primary care only, excluding drugs dispensed from hospitals. However, the vast majority of antiobesity drugs are prescribed from primary care in the UK in both adults and children [10], although often under the advice of hospital specialists. In children and young people, NICE guidance suggests that antiobesity drugs should be initiated from specialist paediatric services but that prescribing is appropriate in primary care (see Table 2). It is thus possible that our data do not include a very small number of initial hospital prescriptions; unfortunately, there are no data to investigate the extent of hospital prescribing. Second, the GPRD does not contain data on socioeconomic status and ethnicity, thus precluding analysis of their impact on prescribing patterns. Third, we had no access to data on reasons for discontinuation of antiobesity drug treatment. However, given that the commonest causes of drug discontinuation are lack of efficacy and adverse effects, we believe that it is reasonable to speculate that discontinuation represents either of these events. A further limitation is the lack of data on BMI. Whereas weight was recorded frequently in the database, there were relatively few recordings of height for most patients. Because of this we were unable to calculate accurate BMI data in relation to prescription dates and thus could not assess either the mean BMI of those prescribed antiobesity drugs, or the change in BMI in those prescribed.

Table 2.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence criteria for use of orlistat and sibutramine in children and adolescents [9]

| • Drug treatment is not generally recommended for children younger than 12 years |

| • In children younger than 12 years, drug treatment may be used only in exceptional circumstances, if severe life-threatening comorbidities (such as sleep apnoea or raised intracranial pressure) are present. Prescribing should be started and monitored only in specialist paediatric settings |

| • In children aged ≥12 years, treatment with orlistat or sibutramine is recommended only if physical comorbidities (such as orthopaedic problems or sleep apnoea) or severe psychological comorbidities are present. Treatment should be started in a specialist paediatric setting, by multidisciplinary teams with experience of prescribing in this age group |

| • Orlistat or sibutramine should be prescribed for obesity in children only by a multidisciplinary team with expertise in: |

| • drug monitoring |

| • psychological support |

| • behavioural interventions |

| • interventions to increase physical activity |

| • interventions to improve diet |

| • Orlistat and sibutramine should be prescribed for young people only if the prescriber is willing to submit data to the proposed national registry on the use of these drugs in young people |

| • After drug treatment has been started in specialist care, it may be continued in primary care if local circumstances and/or licensing allow |

| • If orlistat or sibutramine is prescribed for children, a 6- to 12-month trial is recommended, with regular review to assess effectiveness, adverse effects and adherence |

Comparison with the literature

We are aware of no published population-based data on prescriptions and/or use of orlistat and sibutramine in children and adolescents. The only comparable data on prescription prevalence come from a report of total national prescription counts in England from 1998 to 2005, which were not broken down by age but are almost certain to be almost entirely for adults in whom antiobesity drug use is licensed. This study reported a 25-fold increase in orlistat prescriptions (from 1998) and a fourfold increase in sibutramine prescriptions (from 2001) [10]. We identified a similar increase in orlistat prescriptions in children and adolescents (28-fold increase from 1999) but a much larger increase (16-fold increase from 2001) in sibutramine prescriptions. We found that orlistat prescriptions outweighed those for sibutramine by approximately four to one over our study period; however, this was likely to be an artefact of the later introduction of sibutramine. In 2006, there were only approximately twice as many prescriptions for orlistat as sibutramine, similar to the ratio described for adults [10].

The only comparable data on tolerability and persistence with orlistat and sibutramine in children and young people come from a small number of efficacy studies. For orlistat, published reports conclude repeatedly that it is ‘well tolerated’[17–19]. However, published trial data show that although persistence with orlistat for ≥3 months in clinical trials was markedly greater than in our data, gastrointestinal side-effects were reported in >50%. The largest study of orlistat in adolescents, a randomized placebo-controlled study of 539 subjects over 12 months, reported that 65% of those randomized to orlistat completed 12 months' treatment, and that only 2% (2/357) in the orlistat arm dropped out due to adverse reactions. However, gastrointestinal adverse events were reported by 50% of those taking orlistat [18]. A detailed study of the tolerability of taking orlistat together with a comprehensive behavioural and dietetic programme in 20 adolescents over 3 months found that 85% completed 3 months on orlistat, but that 50–60% reported a combination of unpleasant gastrointestinal side-effects [17]. In an early small open-label randomized controlled trial, gastrointestinal side-effects were reported in all 22 adolescents receiving orlistat, of whom seven (32%) dropped out of the trial during the first month of the trial due to side-effects attributable to orlistat [20].

Similarly for sibutramine, published studies report that this drug is generally well tolerated in adolescents [21–23]. The largest trial, a randomized placebo-controlled trial in 498 obese adolescents over 12 months, reported that 76% of those in the sibutramine arm continued the drug for the full 12-month trial period, with only 6% of subjects withdrawing because of adverse events [22]. In a smaller randomized controlled trial of 60 obese adolescents over 6 months, 93% completed the 6-month trial and no subjects withdrew due to sibutramine side-effects [23]. In a further small randomized trial of 46 obese adolescents, 81% in the sibutramine arm completed the 6-month trial, but none withdrew because of adverse events [24].

Our findings do not support the above reports on tolerability of and persistence with orlistat and sibutramine. In contrast, we found that in general use, one-third or less of prescriptions was continued past 3 months. Although we do not have data on reasons for discontinuation, we believe that this is likely to reflect either poor therapeutic efficacy of the drug in the general population, or poor patient education and preparation before prescription. This poor preparation is likely to be both in terms of high levels of side-effects due to excessive intake of dietary fat [16] or, alternatively, unrealistic expectations of rapid major weight loss, leading to discontinuation when this is not achieved. Although we have no data on reasons for discontinuation in our study, our data suggest that both orlistat and sibutramine are more poorly tolerated and more rapidly discontinued in use in the general population than in highly selected, motivated and supported clinical trial populations. These differences may reflect the routine weight management support programmes that were integral parts of many of the clinical trials of orlistat and sibutramine [17, 18, 22, 23].

A further reason for early discontinuation in this sample may have been the relatively high proportion (approximately 29%) with a comorbid diagnosis of depression, as feelings of hopelessness and negativity may contribute to early discontinuation of the drug. Although we have no further information about the validity of recorded diagnoses of depression, this figure is higher than the 13% reported from population-based estimates of psychological distress in obese UK adolescents [25]. This suggests that in clinical practice, obese adolescents with significant psychological distress may be over-represented in those prescribed antiobesity drugs.

Guidance on appropriate prescribing of orlistat and sibutramine in children and adolescents in the UK were published by NICE in 2006 (see Table 2) [9]. We were unable to assess prescribing in our study against each element of NICE guidance. However, we note that there were a number of children <12 years old prescribed antiobesity drugs, in contravention of the guidance, and that very few of our subjects continued their antiobesity drug for the 6- to 12-month trial suggested by NICE.

We found that use of antiobesity drugs was higher in girls than in boys. This sex ratio is similar to that seen in a population-based study of antiobesity drug use in Taiwanese adults [26], and reflects well-described higher proportions of body-weight concerns in adolescent girls [6].

Conclusion

Prescribing of unlicensed antiobesity drugs in children and adolescents has dramatically increased in the past 8 years. The majority are rapidly discontinued before patients can see clinical benefit, suggesting they are poorly tolerated or poorly efficacious when used in the general population, in contrast to findings from clinical trials. The role of depressive symptoms in early discontinuation is unclear. Further research into the effectiveness and safety of antiobesity drugs in children and adolescents in clinical populations is needed.

Competing interests

None to declare.

R.M.V. is funded by the Higher Education Funding Council and the NHS. A.N. and Y.H. are employed through the School of Pharmacy on noncommercial funding. This study was funded by the European Community 6th framework programme project number LSHB-CT-2005-005216: TEDDY (Task force in Europe for Drug Development for the Young).

REFERENCES

- 1.Lobstein T, Leach RJ. Tackling Obesities: Future Choices—International Comparisons of Obesity Trends, Determinants and Responses—Evidence Review -2 Children. 2nd edn. London: Government Office for Science; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bao W, Srinivasan SR, Wattigney WA, Berenson GS. Persistence of multiple cardiovascular risk clustering related to syndrome X from childhood to young adulthood. The Bogalusa Heart Study. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154:1842–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Freedman DS, Khan LK, Dietz WH, Srinivasan SR, Berenson GS. Relationship of childhood obesity to coronary heart disease risk factors in adulthood: the Bogalusa Heart Study. Pediatrics. 2001;108:712–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.3.712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cross-Government Obesity Unit DoHDoCSaF. Healthy Weight, Healthy Lives: a Cross-Government Strategy for England. London: HM Govermment; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 5.McPherson K, Marsh T, Brown M. Tackling Obesities: Future Choices – Modelling Future Trends in Obesity & Their Impact on Health. 2nd edn. London: Government Office for Science; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taylor SJ, Viner R, Booy R, Head J, Tate H, Brentnall SL, Haines M, Bhui K, Hillier S, Stansfeld S. Ethnicity, socio-economic status, overweight and underweight in East London adolescents. Ethn Health. 2005;10:113–28. doi: 10.1080/13557850500071095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Viner RM, Segal TY, Lichtarowicz-Krynska E, Hindmarsh P. Prevalence of the insulin resistance syndrome in obesity. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90:10–4. doi: 10.1136/adc.2003.036467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Freedman DS, Mei Z, Srinivasan SR, Berenson GS, Dietz WH. Cardiovascular risk factors and excess adiposity among overweight children and adolescents: the Bogalusa Heart Study. J Pediatr. 2007;150:12–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.08.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Obesity: guidance on the prevention, identification, assessment and management of overweight and obesity in adults and children. NICE Clinical Guideline 43; December 2006. [PubMed]

- 10.Shrishanmuganathan J, Patel H, Car J, Majeed A. National trends in the use and costs of anti-obesity medications in England, 1998–2005. J Public Health. 2007;29:199–202. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdm013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barlow SE, Expert Committee Expert committee recommendations regarding the prevention, assessment, and treatment of child and adolescent overweight and obesity: summary report. Pediatrics. 2007;120(Suppl. 4):S164–92. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2329C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rani F, Murray M, Byrne P, Wong ICK. Epidemiology of antipsychotic prescribing to children and adolescents in UK primary care. Pediatrics. 2008;121:1002–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murray ML, de Vries CS, Wong ICK. A drug utilisation study of antidepressants in children and adolescents using the General Practice Research Database. Arch Dis Child. 2004;89:1098–102. doi: 10.1136/adc.2004.064956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walley T, Mantgani A. The UK general practice research database. Lancet. 1997;350:1097–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)04248-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wong IC, Murray ML. The potential of UK clinical databases in enhancing paediatric medication research. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;59:750–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2005.02450.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Molnar D. New drug policy in childhood obesity. Int J Obes (Lond) 2005;29:S62–5. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McDuffie JR, Calis KA, Uwaifo GI, Sebring NG, Fallon EM, Hubbard VS, Yanovski JA. Three-month tolerability of orlistat in adolescents with obesity-related comorbid conditions. Obes Res. 2002;10:642–50. doi: 10.1038/oby.2002.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chanoine JP, Hampl S, Jensen C, Boldrin M, Hauptman J. Effect of orlistat on weight and body composition in obese adolescents: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;293:2873–83. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.23.2873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Henness S, Perry CM. Orlistat: a review of its use in the management of obesity. Drugs. 2006;66:1625–56. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200666120-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ozkan B, Bereket A, Turan S, Keskin S. Addition of orlistat to conventional treatment in adolescents with severe obesity. Eur J Pediatr. 2004;163:738–41. doi: 10.1007/s00431-004-1534-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berkowitz RI, Wadden TA, Tershakovec AM, Cronquist JL. Behavior therapy and sibutramine for the treatment of adolescent obesity: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;289:1805–12. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.14.1805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berkowitz RI, Fujioka K, Daniels SR, Hoppin AG, Owen S, Perry AC, Sothern MS, Renz CL, Pirner MA, Walch JK, Jasinsky O, Hewkin AC, Blakesley VA. Effects of sibutramine treatment in obese adolescents: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:81–90. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-2-200607180-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Godoy-Matos A, Carraro L, Vieira A, Oliveira J, Guedes EP, Mattos L, Rangel C, Moreira RO, Coutinho W, Appolinario JC. Treatment of obese adolescents with sibutramine: a randomized, double-blind, controlled study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:1460–5. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garcia-Morales L, Berber A, Macias-Lara C, Lucio-Ortiz C, Del-Rio-Navarro B, Dorantes-Alvarez LM. Use of sibutramine in obese Mexican adolescents: a 6-month, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group trial. Clin Ther. 2006;28:770–82. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2006.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Viner RM, Haines MM, Taylor SJ, Head J, Booy R, Stansfeld S. Body mass, weight control behaviours, weight perception and emotional well being in a multiethnic sample of early adolescents. Int J Obes (Lond) 2006;30:1514–21. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liou TH, Wu CH, Chien HC, Lin WY, Lee WJ, Chou P. Anti-obesity drug use before professional treatment in Taiwan. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2007;16:580–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]