Abstract

Protein Kinase A-mediated (PKA) phosphorylation of cardiac myosin binding protein-C (cMyBP-C) accelerates the kinetics of cross-bridge cycling and may relieve the tether-like constraint of myosin heads imposed by cMyBP-C. We favor a mechanism in which cMyBP-C modulates cross-bridge cycling kinetics by regulating the proximity and interaction of myosin and actin. To test this idea, we used synchrotron low-angle X-ray diffraction to measure inter-thick filament lattice spacing and the equatorial intensity ratio, I11/I10, in skinned trabeculae isolated from wild-type (WT) and cMyBP-C null (cMyBP-C−/−) mice. In WT myocardium, PKA treatment appeared to result in radial or azimuthal displacement of cross-bridges away from the thick filaments, as indicated by an increase (~50%) in I11/I10 (0.22 ± 0.03 versus 0.33 ± 0.03). Conversely, PKA treatment did not affect cross-bridge disposition in mice lacking cMyBP-C, as there was no difference in I11/I10 between untreated and PKA-treated cMyBP-C−/− myocardium (0.40 ± 0.06 vs 0.42 ± 0.05). While lattice spacing did not change following treatment in WT (45.68 ± 0.84 nm vs 45.64 ± 0.64 nm), treatment of cMyBP-C−/− myocardium increased lattice spacing (46.80 ± 0.92 nm vs 49.61 ± 0.59 nm). This result is consistent with the idea that the myofilament lattice expands following PKA phosphorylation of cardiac troponin I, and when present, cMyBP-C may stabilize the lattice. These data support our hypothesis that tethering of cross-bridges by cMyBP-C is relieved by phosphorylation of PKA-sites in cMyBP-C, thereby increasing the proximity of cross-bridges to actin and increasing the probability of interaction with actin on contraction.

Keywords: protein kinase A phosphorylation, cMyBP-C, contractile protein structure, X-ray, cross-bridge kinetics

Introduction

In myocardium, the phosphorylation status of myofibrillar proteins affects protein function, which leads to changes in Ca2+ activated force and the rate at which force is developed, presumably by changing myofilament structure. In response to β-adrenergic stimulation of the heart, phosphorylation by protein kinase-A (PKA) is a short-term modulator of myocardial work capacity. Cardiac myosin binding protein-C (cMyBP-C), which binds tightly to myosin, is a substrate for PKA, and its phosphorylation is likely to play an important role in the regulation of cardiac contractility,1,2 possibly by accelerating the rates of force development in systole and the rates of relaxation in diastole.3,4 Conversely, the lack of cMyBP-C3–8 or decreased levels of cMyBP-C phosphorylation9 lead to cardiac dysfunction.

While cAMP-activation of PKA targets cMyBP-C in the thick filament, PKA targets primarily troponin I (cTnI) in the thin filament. In skinned myocardium, phosphorylation of cTnI regulates the Ca2+-sensitivity of force, and phosphorylation of cMyBP-C regulates the rates of cross-bridge cycling.3,4 With regard to the role of cMyBP-C in the regulation of contraction kinetics, we favor a working model of regulation in which PKA phosphoryation of cMyBP-C accelerates the kinetics of cross-bridge cycling and stretch activation (and presumably systolic ejection) by regulating the proximity and subsequent interaction of myosin and actin. In examining low-resolution electron micrographs of isolated thick filaments, PKA phosphorylation of cMyBP-C appears to increase the diameter of thick filaments, which has been interpreted as radial displacement of cross-bridges away from the thick filament backbone10,11; however, this interpretation has yet to be tested in intact muscles.

Emerging evidence suggests that cross-bridge kinetics and the level of cooperative activation of the thin filament change by a structural mechanism in which cMyBP-C affects the location of cross-bridges relative to the thick filament backbone. We have recently shown that myocardium from mutant mice lacking cMyBP-C (cMyBP-C−/−) differ from wild-type myocardium (WT) in that myosin heads are located further from the surface of the thick filament and closer to actin.12 Similarly to the effect of ablation, PKA-mediated phosphorylation of cMyBP-C has been postulated to relieve the collar-like constraint of myosin heads.10 In this regard, both phosphorylation and ablation of cMyBP-C appear to have similar effects to accelerate cross-bridge cycling kinetics.3,4 It remains unresolved whether the structural mechanisms underlying the accelerated kinetics are the same in the two cases.

The kinetics of myocardial force development are accelerated by β-adrenergic agonists, in part due to PKA-mediated phosphorylation of myofibrillar proteins, especially cMyBP-C.13 We propose that phosphorylation of cMyBP-C causes myosin cross-bridges to move radially or azimuthally toward the thin filament by alleviating a physical constraint, similar to the model proposed by Winegrad10, thereby accelerating the rate of binding to actin during contraction. To determine whether cMyBP-C phosphorylation affects cross-bridge position, we treated WT and cMyBP-C−/− myocardium with PKA to induce phosphorylation of myofibrillar proteins (including cMyBP-C in WT and excluding cMyBP-C in cMyBP-C−/−) and then assessed the ratio of the 1,1 to the 1,0 equatorial reflections (I11/I10), as a measure of the proximity of myosin heads to actin in myocardium under resting conditions. We found that only wild-type myocardium exhibited changes in equatorial intensities due to PKA phosphorylation, from a typical relaxed pattern towards that of a contracting or rigor pattern. In contrast, cMyBP-C−/− null myocardium showed no change before and after PKA treatment, presumably since the structural constraint on myosin position was already relieved due to ablation of cMyBP-C.5,12

Materials and Methods

Experimental animals

Homozygous cMyBP-C null mice (cMyBP-C−/−) were generated as described4. Wild-type (WT) SV/129-strain mice (6–12 months old; either sex) were obtained from Taconic Farms (Germantown, NY). Animal usage was conducted in accordance with institutional guidelines using protocols approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health.

Experimental solutions

Experimental solutions for dissections and X-ray diffraction measurements were prepared as described.12 Additionally, mechanical measurements made on skinned trabeculae used solutions containing different amounts of [Ca2+]free (pCa 6.1 to 5.3), which were made by mixing pCa 9.0 and pCa 4.5 solutions (pCa 4.5 solution contained the same concentrations of chemicals as pCa 9.0 except for (mM) 7.01 CaCl2, 5.29 MgCl2, and 4.72 ATP). Pre-activating solution alternatively contained (mM) 0.07 EGTA, 5.29 MgCl2, and 4.67 ATP.14,15

Isolation of skinned trabeculae

Mice were anesthetized and euthanized as described.12 Hearts were rapidly excised and placed in a petri dish containing modified Tyrodes solution [(mM) 120 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1.2 MgSO4, 19 NaHCO3, 1.2 Na2HPO4, 10 Glucose, 1 CaCl2, and 30 2,3-butanedione monoxime (BDM), and the pH was adjusted to 7.0 by bubbling with 95% O2/5% CO2 for 30 minutes16,17]. Trabeculae were dissected, skinned, and stored as described.12

Trabeculae mounting

Trabeculae were mounted in a simple X-ray chamber18 and sarcomere length (SL) was set19,20 to ~2.15 ± 0.01 µm, as described.12 For PKA treatment experiments, mounted trabeculae were incubated for one hour (22 °C) in pCa 9.0 solution which contained 1 U/µl Protein Kinase A catalytic subunit from bovine heart (Sigma, #P2645) and 6 mM dithiotheitol (DTT). PKA was washed out of the myocardial preparations by 3 washes of pCa 9.0 in the ~ 250 µl volume of the chamber for a total of 30 minutes21,3,4 followed by a final soak in a fresh bath of pCa 9.0 used during exposure of myocardium to the X-ray beam.

X-ray diffraction and analysis

X-ray experiments were performed at 22 °C using the small-angle instrument on the BioCAT undulator-based beamline 18-D at the Advanced Photon Source, Argonne National Laboratory20,22 as described.12 Spacings of the 1,0 and 1,1 equatorial reflections were converted to d10 lattice spacings using Bragg’s Law and can be converted to inter-thick filament spacing by multiplying d10 by 2/√3.23 Intensities of the 1,0 and 1,1 equatorial reflections were determined from one-dimensional projections along the equator and analyzed as described,23 independently by three people and the results averaged. I11/I10 intensity ratios can be used to estimate shifts of mass (presumably cross-bridges) from the region of the thick filament to region of the thin filament.24,25

Phosphoprotein-staining

Following exposure to the X-ray beam, the region of trabeculae between aluminum t-clips were dissolved and stored in 12 µl-aliquots of SDS-buffer. Proteins in myocardial samples were separated by 10%-SDS (w/v) PAGE. Pro-Q Diamond Phosphoprotein gel-stain analysis (Molecular Probes) was performed to confirm phosphorylation state of individual phosphoproteins. The strength of the emitted signal correlates with the number of phosphate groups. SYPRO Ruby protein gel-stain (Molecular Probes) was used in conjunction with Pro-Q Diamond stain to determine the total protein load of individual proteins, and thereby provide a measure of the phophorylation level of specific myofibrillar proteins normalized to the total amount of protein of interest and thus correct for differential protein loading due to variations in experimental preparation size. Here, quantitation of cTnI and cMyBP-C phosphorylation in myocardial preparations under basal and PKA-treated conditions was done. [Preparations were analyzed individually and contained unknown concentrations of total protein. Typically, skinned trabeculae used for X-ray experiments contain ~ 15 µg of total myofibril protein, as determined by colorimetric detection and quantification using a bicinchoninic acid assay (Pierce)].

A Bio-Rad storage phosphor scanner (Molecular Imager F/X) with laser excitation filter at 532 nm and long-pass emission filter at 555 nm was used to capture Pro-Q Diamond fluorescence image. An EC-3 imaging system (UVP) UV source with excitation filter at 302 nm and long-pass emission filter at 560 nm was used to capture SYPRO Ruby fluorescence images. The program Laser-Pix (Bio-Rad) was used to determine the total pixel count and relative intensity of individual bands of interest following subtraction of background intensity. The intensity of each band was corrected for variability in gel-to-gel conditions using linear regression analysis of a dilution series of an ova-albumin/albumin weight standard (loading 50–1000 ng) to create a standard curve relating band intensity [arbitrary units, (A.U.)] to the amount of phosphorylated protein and total protein (ng) for both stains in each gel.

Additionally, myofibril preparations26 from WT and cMyBP-C−/− mice (n=4) were separated by 5%-SDS (w/v) PAGE and stained with Pro-Q Diamond. Basal phosphorylation of titin does not change with ablation of cMyBP-C, since the average slopes of phospho-intensities of the N2B isoform and T2 degradation products of titin using regression analysis are not different in WT and cMyBP-C−/− myocardium [(in A.U.) 29.46 ± 3.27 in WT and 30.22 ± 3.17 in cMyBP-C−/−].

Mechanical experiments

Total force generated by skinned trabeculae at each pCa and the rate of force development were measured and assessed, as described by Stelzer,5 except that a different motor model (6800HP; Cambridge Tech.) was used in the apparatus 27 and SL was set to ~2.16 µm. The changes in motor position and force signals were digitized at 1 kHz, using a 12-bit A/D converter (model AT-MIO-16F-5; National Instruments Corp.), and displayed and saved to disk for later analysis using computer software (SLControl).28 Rate constants of force redevelopment (ktr) were estimated by fitting the data with a single exponential equation.30,31

Statistics

Data are expressed as means ± SEM. A two-tailed t-test for unpaired samples or a paired t-test was used to post hoc test significance (p<0.05), as appropriate.

Results

X-ray experiment analysis

Intensity ratios determined from the 1,0 and 1,1 equatorial reflections from WT and cMyBP-C−/− skinned myocardium (Figure 1) were used to investigate the role of cMyBP-C phosphorylation on the distribution of cross-bridge mass between the thick and thin filaments. These measurements were made under relaxed conditions (pCa 9.0) to avoid possible confounding effects due to attachment of cross-bridges to thin filaments in activated muscle. I11/I10 ratios in trabeculae from WT mice were found to be significantly greater (~50%, p<0.05) in WT myocardium treated with PKA (0.33 ± 0.03, n=17) than in untreated WT myocardium (0.22 ± 0.03, n=6) (Figure 2). In contrast, I11/I10 in trabeculae from cMyBP-C−/− mice were not significantly different between cMyBP-C−/− myocardium (0.40 ± 0.06, n=4) and cMyBP-C−/− myocardium treated with PKA (0.42 ± 0.05, n=5). These results suggest that in resting myocardium, phosphorylation of PKA-sites in cMyBP-C leads to a net transfer of mass from the region of the thick filaments to the thin filaments.

Figure 1.

Intensity traces along the equator from X-ray patterns of untreated (- PKA) and treated (+ PKA) WT and cMyBP-C knockout (KO) skinned myocardium.

Figure 2.

a) Ratio of intensities of the 1,1 and 1,0 equatorial X-ray reflections (I11/I10) from WT or cMyBP-C knockout (KO) skinned myocardium with and without PKA treatment. (*) Asterisks denote significant difference in I11/I10 with PKA treatment, p<0.05. b)d10 lattice spacing from WT and KO with and without PKA treatment. (†) Crosses denote significant difference in d10, p<0.02. NS indicates no significant difference following PKA treatment.

The separations of the 1,0 and 1,1 equatorial reflections in diffraction patterns were converted to d10 lattice spacings to investigate the roles of cMyBP-C- and cTnI-phosphorylation on the inter-filament lattice spacing. As shown in Figure 2, d10 lattice spacings did not change in WT myocardium following PKA treatment (45.65 ± 0.99 nm, n=7 vs 45.64 ± 0.64 nm, n=17). Conversely, d10 lattice spacings in cMyBP-C−/− myocardium were significantly increased following PKA treatment (46.80 ± 0.92 nm, n=9 versus 49.61 ± 0.59 nm, n=10). These results suggest that when cMyBP-C is absent, the distance between neighboring thick filaments in the hexagonal lattice is increased following PKA treatment.32

Phosphoprotein-staining

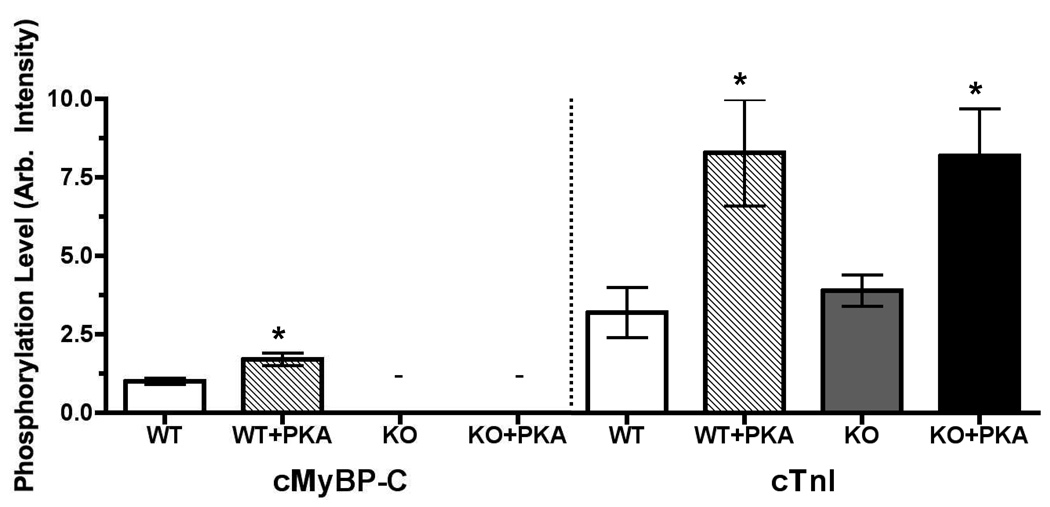

Gel analysis of protein phosphorylation using SYPRO-Ruby and Pro-Q Diamond staining (Figure 3 and Figure 4) showed that basal levels of cTnI phosphorylation were not different in WT and cMyBP-C−/− myocardium before PKA treatment, consistent with earlier results.3,4 PKA treatment phosphorylated both cTnI and cMyBP-C in WT myocardium but phosphorylated only cTnI in cMyBP-C−/− myocardium (Figure 3 and Figure 4). Titin is phosphorylated by PKA33 (2.71 ± 0.25 vs 3.75 ± 0.37, p<0.05) in our preparations (not shown), and also a distinct band migrates just slower than desmin in the 60–70kD MW range that appears after PKA treatment [0.88 ± 0.20 vs 3.94 ± 0.69]. Since PKA phosphorylation has no impact on the disposition of cross-bridges in cMyBP-C−/− in addition to that caused by ablation, PKA phosphorylation of other myofibrillar proteins appear to have no effect on the location of cross-bridges. However, we note that there are myofibrillar proteins whose effects of phosphorylation have not yet been resolved, such as intermediate filament proteins.

Figure 3.

Phosphorylation status of myofibrillar proteins from WT and cMyBP-C knockout (KO) myocardial samples with (+) and without (−) PKA treatment was assessed following exposure to X-ray beam, as shown in this representative SDS-PAGE. SR indicates SYPRO Ruby-stained gel for relative abundance of total proteins. PQ indicates Pro-Q Diamond-stained gel specific for relative abundance of phosphorylated proteins.

Figure 4.

Basal and PKA-induced phosphorylation levels of the myofibrillar proteins cMyBP-C and cTnI were determined in WT and cMyBP-C knockout (KO) myocardial samples with (+) and without (−) PKA treatment following X-ray diffraction experiments. Phosphorylation status was determined by dividing Pro-Q Diamond-stained intensity by SYPRO Ruby-stained intensity. Lanes containing KO samples (−) had no visible bands in the cMyBP-C region. (*) Asterisks denote significant difference in phosphorylation status of cMyBP-C or cTnI from WT and KO with and without PKA treatment. There was no difference between basal or PKA-induced phosphorylation levels of cTnI when comparing KO and WT samples.

Mechanical measurements

The decrease in the Ca2+ sensitivity of force with PKA treatment was similar in WT and cMyBP-C−/− myocardium (Table I), as reported previously.3,4 During sub-maximal Ca2+ activation, the rate constant of force development (ktr), a measure of cross-bridge cycling kinetics, increased following PKA treatment in WT myocardium, but did not change following PKA treatment in cMyBP-C−/− myocardium (Table I).

Table I. Effects of PKA treatment on mechanical properties of WT and cMyBP-C−/− skinned myocardium.

I. Data are means ± SEM. Resting force was measured at pCa 9.0. Maximum force and the rate constant of force redevelopment (ktr) were measured at pCa 4.5. pCa50 and nH values were derived by fitting the force-pCa relationships to a Hill equation described in Materials and Methods.

| Resting Force (mN/mm2) | Max Ca2+ Activated Force (mN/mm2) | Hill Coefficient | Ca2+ Sensitivity of Force | Max Rate of Force Redevelopment | ktr value at ~0.30 P/Po | ktr value at ~0.50 P/Po | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT (−) PKA | 0.88 ± 0.13 | 19.16 ± 1.59 | 2.24 ± 0.07 | 5.73 ± 0.02 | 22.60 ± 1.67 | 3.19 ± 0.36 | 5.19 ± 0.49 |

| n=7 (+) PKA | 0.70 ± 0.14 | 17.40 ± 1.22 | 2.26 ± 0.07 | 5.58 ± 0.02† | 22.60 ± 1.95 | 7.43 ± 0.41* | 10.17 ± 0.63* |

| KO (−) PKA | 0.99 ± 0.17 | 17.55 ± 1.45 | 2.04 ± 0.06 | 5.74 ± 0.02 | 24.54 ± 1.60 | 9.46 ± 0.75 | 14.02 ± 1.18 |

| n=7 (+) PKA | 0.66 ± 0.14 | 15.04 ± 1.09 | 1.76 ± 0.08 | 5.63 ± 0.02† | 25.29 ± 1.52 | 9.52 ± 0.83 | 14.36 ± 1.41 |

Crosses denote decreases in pCa50 following PKA treatment of WT or cMyBP-C (KO) myocardium.

Asterisks denote an increase in the rate of force development (ktr) for a given level of Ca2+ activated force (P/Po) following PKA treatment of WT or KO myocardium.

Discussion

The primary result of this study is that when the PKA-sites in the cardiac isoform of MyBP-C are phosphorylated, myosin cross-bridges assume positions further from the surface of the thick filament and closer to the thin filament. This conclusion follows from the observation that the I11/I10 ratio was significantly greater in WT myocardium treated with PKA than untreated WT myocardium, and that PKA treatment did not change the I11/I10 ratio in cMyBP-C−/− null myocardium. This finding suggests that cMyBP-C acts to regulate the proximity and interaction of myosin with actin upon contraction, and this mechanism is modulated by β-adrenergic stimulation through phosphorylation of PKA-sites in cMyBP-C. cMyBP-C is assumed to normally act as a structural restraint on every third crown of heads in the C-zone.34 The structural conformation of myosin heads in the relaxed state was recently revealed by Zoghbi et al. (2008)35. It appears that only crown 1 of 3 is constrained and dependent upon the presence of cMyBP-C, and that at least 3 of the 11 cMyBP-C domains lay on the thick filament surface in this crown. We favor a model in which phosphorylation of cMyBP-C relieves this restraint such that those cross-bridges move closer to the thin filament, and thereby increase the probability of their interaction with actin upon active contraction. The displacement of cross-bridges accelerates the cooperative recruitment of additional cross-bridges to force-generating states to increase the rate of force development. Such a mechanism is consistent with earlier suggestions that cMyBP-C serves as a mechanical tether on myosin that may be altered by phosphorylation, possibly due to disruption of cMyBP-C binding to the S2-domain of myosin.36–38 Similarly, the closer proximity of myosin heads to the thin filaments, which would presumably decrease the time taken to cooperatively activate the thin filament, could account for the faster kinetics of force development in PKA-treated WT myocardium compared to control myocardium, as reported here and previously.3,4

PKA phosphorylation of myofibrillar proteins, such as cMyBP-C, involves the addition of a negatively charged phosphate (PO4) group on a serine or threonine residue, which is thought to induce a conformational change in the structure of the protein. While we have found PKA phosphorylation of cMyBP-C to modulate the disposition and availability of cross-bridges to actin, it remains to be elucidated whether this mechanism of cMyBP-C function can be attributed to the negative charge associated with phosphorylation. At least 3 domains near the C-terminal region of cMyBP-C run along the thick filament surface,35,39 and likely interact with titn and light meromyosin (LMM) in crown 1, and thereby anchor cMyBP-C to the thick filament. Domains near the N-terminal region of cMyBP-C are thought to extend from the filament surface39–41 and bind to the S2-domain of myosin in crown 1, thereby limiting the availability of S1 to actin. It is possible that the negative charge associated with phosphorylation of cMyBP-C is sufficient to relieve a physical constraint on cross-bridges, possibly by disrupting cMyBP-C binding to the S2-region of myosin.42,43 This, in turn, would allow cross-bridges to move away from the surface of thick filaments at rest, and accelerate cross-bridge binding to actin upon contraction by increasing the cooperative spread of thin filament activation. It is possible, however, that cMyBP-C influences the binding of heads to actin in a mechanism independent of a tether,42 in such a way that S2 could play a regulatory role in contraction,39 or that cMyBP-C binds actin,41 but it remains unresolved whether these interactions normally occur in vivo.

Force development in myocardium is a highly cooperative process44 in which initial cross-bridge binding to the thin filaments recruits additional cross-bridge binding to actin and also increases Ca2+ binding to troponin C (TnC). In this manner, increasing the availability of cross-bridges to actin would contribute to increasing the number of cross-bridges that are strongly bound to the thin filaments, and consequently, we would expect even a small change in the disposition of myosin heads to considerably change the rates of force development, whereby cross-bridge cycling kinetics would be accelerated by eliminating, or significantly accelerating, cooperative cross-bridge recruitment.3 When we consider our structural measurements in the context of the findings by Stelzer et al. (2006, 2007),3,4 who used the same mouse lines and PKA treatment, it appears that the cross-bridge kinetics are faster when cross-bridges are closer to actin at resting force. This conclusion follows from the results that both genetic ablation12 and PKA phosphorylation of cMyBP-C (data presented here) result in radial or azimuthal displacement of cross-bridges, and both genetic ablation5 and PKA phosphorylation3 (see also Table I) of cMyBP-C result in faster rates of force development and shorter times to peak of delayed force development following a rapid stretch to a new length (stretch activation). It seems likely, then, that changes in the disposition of cross-bridges during diastole may affect the rate of cross-bridges binding to actin during systole (i.e., how fast cross-bridges attach to the thin filament). Indeed, Pearson and colleagues recently demonstrated (2007)45 that the number of attached cross-bridges and the rate of force generation proportionally increase as the result of a greater proximity of myosin filaments to actin.

Our finding that inter-filament lattice spacing does not change in WT myocardium when subject to PKA phosphorylation is consistent with results by Toh et al. (2006),46 whereby β-adrenergic stimulation leading to cascading events, including PKA phosphorylation of cMyBP-C and cTnI, does not change lattice spacing. In contrast to WT myocardium, PKA phosphorylation of cMyBP-C−/− myocardium increased lattice spacing, which is consistent with previous inferences32 that PKA-dependent phosphorylation of cTnI caused expansion of the myofilament lattice, and that this effect is greater in the absence of cMyBP-C. Interestingly, Konhilas et al. (2003)32 found lattice spacing to expand slightly in PKA-treated WT myocardium. We believe our results differ from the previous study because we took care to reduce the level of basal phosphorylation of regulatory myosin light chains (RLCs) by BDM-treatment47 during our trabeculae dissection (see Materials and Methods); phosphorylation of RLC has been shown to have similar effects as cMyBP-C phosphorylation on force generation16,47 by inducing movement of the myosin head away from the thick filament backbone48,49 and may have confounding effects on observations concerning myofilament structure. When we compared results of WT myocardium from our previous study12, in which RLC was basally phosphorylated, to results in the present study, in which RLC was dephosphorylated, we found that dephosphorylation of RLC slightly, but significantly, expanded lattice spacing (42.95 ± 0.43 nm vs 45.65 ± 0.99 nm) and decreased the I11/I10 (0.28 ± 0.01 vs 0.22 ± 0.03). Therefore, it seems likely that the effect of cTnI phosphorylation on lattice spacing observed by Konhilas et al. (2003)32 was masked in our study by dephosphorylation of RLC. These results also suggest that cMyBP-C and RLC may have similar effects on myofilament structure. With regard to phosphorylation of the contractile proteins related to the inherent mechanical properties of myocardium, such a finding would be expected, since the phosphorylation status of both cMyBP-C and RLC affect in the kinetics of force development in cardiac muscle. In either case, it appears that phosphorylation of cTnI in the absence of cMyBP-C increases the spacing between thick filaments.

Our studies using X-ray diffraction of whole muscle are consistent with electron microscopy (EM) studies of isolated thick filaments,10,11 in which the filament diameter in the cross-bridge containing regions were greater in PKA treated than in control filaments. Phosphorylation of the thick filament in the absence of the thin filament appeared to result in a looser packing of myosin, such that the thickness of PKA treated filaments was ~ 2–5 nm greater than untreated filaments. The increased thickness was interpreted as a population of cross-bridges that extended away from the backbone of the thick filament due to phosphorylation of cMyBP-C. In some cases, however, untreated filaments contained cross-bridges that extended the same distance as the PKA treated filaments. Weisberg and Winegrad (1996)10 suggest that these cases are most likely associated with phosphorylated cMyBP-C in the untreated filament. It is thus important to consider phosphorylation status in cardiac preparations when interpreting the results of structural studies, since phosphorylation appears to change myofilament structure. In our study, phosphoprotein staining analysis was used to determine the phosphorylation status of myocardium used in our X-ray studies; in two of nine cases of untreated WT trabeculae, cMyBP-C phosphorylation was suprabasal by more than two-fold as compared to all other untreated WT trabeculae, and the ratio of cMyBP-C phosphorylation to cTnI phosphorylation was nearly three-fold greater than all other WT preparations. These observations are consistent with the variability in the level of basal phosphorylation of contractile proteins reported previously.50,51 Consequently, these cases of suprabasal cMyBP-C phosphorylation were excluded when assessing the effect of cMyBP-C phosphorylation on cross-bridge disposition.

As our understanding of the mechanism by which cMyBP-C modulates cardiac contractility improves, it is becoming clear that its phosphorylation by PKA is an important regulatory mechanism that contributes to increased cardiac output in response to β-adrenergic stimulation. We propose that cMyBP-C normally acts to slow the rates of cross-bridge attachment and the transition to force-generating states. However, during adrenergic stimulation, phosphorylation of cMyBP-C accelerates the rates of cross-bridge cycling early in systole as a consequence of the closer juxtaposition of myosin heads nearer to actin in diastole, and thereby matches the increased heart rate. Conversely, PKA phosphorylation of cTnI acts to decrease the Ca2+-binding affinity of troponin, which causes an earlier onset of relaxation, and thus provides adequate time for diastolic filling. In this scheme, the balance of PKA-mediated phosphorylations of cMyBP-C and cTnI act to finely tune durations of systolic ejection and diastolic filling in order to optimize contraction during accelerated systolic ejection.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Sandy Dunning (for assistance in data collection) and J.R. Patel (for advice in experimental design). We especially thank Heather King, Anton Kovalsky, and Krystyna Shioura (for assistance in analysis of diffraction patterns).

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by an AHA predoctoral fellowship (BAC) and by NIH HL-R01-82900 (RLM). Use of the Advanced Photon Source was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Basic Energy Sciences, Office of Science, under contract No. W-31-109-ENG-38. BioCAT is a National Institutes of Health-supported Research Center RR-08630. The content is the sole responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the official views of the National Center for Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Disclosures: None

References

- 1.de Tombe PP. Myosin binding protein C in the heart. Circ Res. 2006;98:1234–1236. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000225873.63162.c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Winegrad S. Myosin binding protein-C – a potential regulator of cardiac contractility. Circ Res. 2002;86:6–7. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.1.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stelzer JE, Patel JR, Moss RL. Protein kinase-A mediated acceleration of the stretch activation response in murine skinned myocardium is eliminated by ablation of cMyBP-C. Circ Res. 2006;99:884–890. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000245191.34690.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stelzer JE, Patel JR, Walker JW, Moss RL. Differential roles of cardiac myosin-binding protein C and cardiac troponin I in the myofibrillar force responses to protein kinase A phosphorylation. Circ Res. 2007;101:503–511. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.153650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stelzer JE, Fitzsimons DP, Moss RL. Ablation of myosin binding protein-C accelerates force development in mouse myocardium. Biophys J. 2006;90:4119–4127. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.078147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harris SP, Bartley CR, Hacker TA, McDonald KS, Douglas PS, Greaser ML, Powers PA, Moss RL. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in cardiac myosin binding protein-C knockout mice. Circ Res. 2002;90:594–601. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000012222.70819.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Palmer BM, McConnell BK, Li GH, Seidman CE, Seidman JG, Irving TC, Alpert NR, Maughan DW. Reduced cross-bridge dependent stiffness of skinned myocardium from mice lacking cardiac myosin binding protein-C. Mol Cell Biochem. 2004;263:73–80. doi: 10.1023/B:MCBI.0000041849.60591.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Palmer BM, Georgakopoulos D, Janssen PM, Wang Y, Alpert NR, Belardi DF, Harris SP, Moss RL, Burgon PG, Seidman CE, Seidman JG, Maughan DW, Kass DA. Role of cardiac myosin binding protein C in sustaining left ventricular systolic stiffening. Circ Res. 2004;94:1249–1255. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000126898.95550.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sadayappan S, Gulick J, Osinska H, Martin LA, Hahn HS, Dorn GW 2nd, Klevitsky R, Seidman CE, Seidman JG, Robbins J. Cardiac myosin-binding protein-C phosphorylation and cardiac function. Circ Res. 2005;97:1156–1163. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000190605.79013.4d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weisberg A, Winegrad S. Alteration of myosin cross-bridges by phosphorylation of myosin-binding protein C in cardiac muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:8999–9003. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.17.8999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weisberg A, Winegrad S. Relation between cross-bridge structure and actomyosin ATPase activity in rat heart. Circ Res. 1998;83:60–72. doi: 10.1161/01.res.83.1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Colson BA, Bekyarova T, Fitzsimons DP, Irving TC, Moss RL. Radial displacement of myosin cross-bridges in mouse myocardium due to ablation of myosin binding protein-C. J Mol Biol. 2007;367:36–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.12.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Okagaki T, Weber FE, Fischman DA, Vaughan KT, Mikawa T, Reinach FC. The major myosin-binding domain of skeletal muscle MyBP-C (C protein) resides in the COOH-terminal, immunoglobulin C2 motif. J Cell Biol. 1993;123:619–626. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.3.619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fabiato A. Computer programs for calculating total from specified free and free from specified total ionic concentrations in aqueous solutions containing multiple metals or ligands. Meth Enzymol. 1998;157:378–417. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(88)57093-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Godt RE, Lindley BD. Influence of temperature upon contractile activation and isometric force production in mechanically skinned muscle fibers of the frog. J. Gen. Physiol. 1982;80:279–297. doi: 10.1085/jgp.80.2.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Olsson MC, Patel JR, Fitzsimons DP, Walker JW, Moss RL. Basal myosin light chain phosphorylation is a determinant of Ca2+ sensitivity of force and activation dependence of the kinetics of myocardial force development. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;287:H2712–H2718. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01067.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davis JS, Satorius CL, Epstein ND. Kinetic effects of myosin regulatory light chain phosphorylation on skeletal muscle contraction. Biophys J. 2002;83:359–370. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75175-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Farman GP, Walker JS, de Tombe PP, Irving TC. Impact of osmotic compression on sarcomere structure and myofilament calcium sensitivity of isolated rat myocardium. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;291:H1847–H1855. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01237.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fan DS, Wannenburg T, de Tombe PP. Decreased myocyte tension development and calcium responsiveness in rat right ventricular pressure overload. Circulation. 1997;95:2312–2317. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.9.2312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Irving TC, Fischetti R, Rosenbaum G, Bunker GB. Fiber diffraction using the BioCAT undulator beamline at the Advanced Photon Source. Nuclear Instr Methods. 2000;448:250–254. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patel JR, Fitzsimons DP, Buck SH, Muthuchamy M, Wieczorek DF, Moss RL. PKA accelerates rate of force development in murine skinned myocardium expressing alpha- or beta-tropomyosin. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;280:H2732–H2739. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.6.H2732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Irving TC, Konhilas J, Perry D, Fischetti R, de Tombe PP. Lattice spacings in skinned rat trabeculae as a function of sarcomere length in rat myocardium. Am J Physiol. 2000;279:H2568–H2573. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.5.H2568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Irving TC, Millman B. Changes in thick filament structure during compression of the filament lattice in relaxed frog sartorius muscle. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 1989;10:385–396. doi: 10.1007/BF01758435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haselgrove JC, Huxley HE. X-ray evidence for radial cross-bridge movement and for the sliding filament model in actively contracting muscle. J Mol Biol. 1973;77:549–568. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(73)90222-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Podolsky RJ, St. Onge R, Yu L, Lymn RW. X-ray diffraction of actively shortening muscle. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 1976;73:813–817. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.3.813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tardiff JC, Hewett TE, Factor SM, Vikstrom KL, Robbins J, Leinwand LA. Expression of the beta (slow)-isoform of MHC in the adult mouse heart causes dominant-negative functional effects. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;278:H412–H419. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.278.2.H412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moss RL. Sarcomere length-tension relations of frog skinned muscle fibers during calcium activation at short lengths. J Physiol. 1979;285:H2857–H2864. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1979.sp012845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Campbell KS, Moss RL. SLControl: PC-based data acquisition and analysis for muscle mechanics. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;285:H2857–H2864. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00295.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brenner B, Eisenberg E. Rate of force generation in muscle: correlation with actomyosin ATPase activity in solution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83:3542–3546. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.10.3542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fitzsimons DP, Patel JR, Campbell KS, Moss RL. Cooperative mechanisms in the activation dependence of the rate of force development in skinned skeletal muscle fibers. J Gen Physiol. 2001;117:133–148. doi: 10.1085/jgp.117.2.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Regnier M, Martyn DA, Chase PB. Calcium regulation of tension redevelopment kinetics with 2-deoxy-ATP or low [ATP] in rabbit skeletal muscle. Biophys J. 1998;74:2005–2015. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77907-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Konhilas JP, Irving TC, Wolska BM, Jweied EE, Martin AF, Solaro RJ, de Tombe PP. Troponin I in the murine myocardium: influence on length-dependent activation and interfilament spacing. J Physiol. 2003;547:951–961. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.038117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fukuda N, Granzier HL, Ishiwata S, Kurihara S. Physiological functions of the giant elastic protein titin in mammalian striated muscle. J Physiol Sci. 2008 doi: 10.2170/physiolsci.RV005408. [In press] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Al-Khayat HA, Morris EP, Kensler RW, Squire JM. 3D structure of relaxed fish muscle myosin filaments by single particle analysis. J Struct Biol. 2006;155:202–217. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2006.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zoghbi ME, Woodhead JL, Moss RL, Craig R. Three-dimensional structure of vertebrate cardiac muscle myosin filaments. PNAS. 2008;105:2386–2390. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708912105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hofmann PA, Hartzell HC, Moss RL. Alterations in Ca2+ sensitive tenson due to partial extraction of C-protein from rat skinned cardiac myocytes and rabbit skeletal muscle fibers. J Gen Physiol. 1991;97:1141–1163. doi: 10.1085/jgp.97.6.1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gautel M, Zuffardi O, Freiburg A, Labeit S. Phosphorylation switches specific for the cardiac isoform of myosin binding protein-C: a modulator of cardiac contraction? EMBO J. 1995;14:1952–1960. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07187.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kunst G, Kress KR, Gruen M, Uttenweiler D, Gautel M, Fink RH. Myosin binding protein C, a phosphorylation-dependent force regulator in muscle that controls the attachment of myosin heads by its interaction with myosin S2. Circ Res. 2000;86:51–58. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Flashman E, Redwood C, Moolman-Smook J, Watkins H. Cardiac myosin binding protein C: Its role in physiology and disease. Circ Res. 2004;94:1279–1289. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000127175.21818.C2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moolman-Smook J, Flashman E, de Lange W, Li Z, Corfield V, Redwood C, Watkins H. Identification of novel interactions between domains of myosin-binding protein C that are modulated by hypertrophic cardiomyopathy missense mutations. Circ Res. 2002;91:704–711. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000036750.81083.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Squire JM, Luther PK, Knupp C. Structural evidence for the interaction of C-protein (MyBP-C) with actin and sequence identification of a possible actin-binding domain. J Mol Biol. 2003;331:713–724. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00781-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Harris SP, Rostkova E, Gautel M, Moss RL. Binding of myosin binding protein-C to myosin subfragment S2 affects contractility independent of a tether mechanism. Circ Res. 2004;95:930–936. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000147312.02673.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Starr R, Offer G. The interaction of C-protein with heavy meromyosin and subfragment-2. Biochem J. 1978;171:813–816. doi: 10.1042/bj1710813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moss RL, Razumova M, Fitzsimons DP. Myosin crossbridge activation of cardiac thin filaments: implications for myocardial function in health and disease. Circ Res. 2004;94:1290–1300. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000127125.61647.4F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pearson JT, Shirai M, Tsuchimochi H, Schwenke DO, Ishida T, Kangawa K, Suga H, Yahi N. Effects of sustained length-dependent activation on in situ cross-bridge dynamics in rat hearts. Biophys J. 2007;93:4319–4329. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.111740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Toh R, Shinohara M, Takay T, Yamashita T, Masuda S, Kawashima S, Yokoyama M, Yagi N. An X-ray diffraction study on mouse cardiac cross-bridge function in vivo: effects of adrenergic β-stimulation. Biophys J. 2006;90:1723–1728. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.074062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stelzer JE, Patel JR, Moss RL. Acceleration of stretch activation in murine myocardium due to phosphorylation of myosin regulatory light chain. J Gen Physiol. 2006;128:261–272. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200609547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Levine RJC, Kensler RW, Yang Z, Stull JT, Sweeney HL. Myosin light chain phosphorylation affects the structure of rabbit skeletal muscle thick filaments. Biophys J. 1996;71:898–907. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79293-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yang Z, Stull JT, Levin RJC, Sweeney HL. Changes in interfilament spacing mimic the effects of myosin regulatory light chain phosphorylation in rabbit psoas fibers. J Struct Biol. 1998;122:139–148. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1998.3979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Verduyn SC, Zaremba R, van der Velden J, Stienen GJM. Effects of contractile protein phosphorylation on force development in permeabilized rat cardiac myocytes. Basic Res Cardiol. 2007;102:476–487. doi: 10.1007/s00395-007-0663-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.van der Velden J, Papp Z, Boontje NM, Zaremba R, de Jong JW, Janssen PM, Hasenfuss G, Stienen GJM. The effect of myosin light chain 2 dephosphorylation on Ca2+-sensitivity of force is enhanced in failing human hearts. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;57:505–514. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00662-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.