Abstract

Background

The optimal production of three-dimensional cartilage in vitro requires both inductive factors and specified culture conditions (e.g., hydrostatic pressure [HP], gas concentration, and nutrient supply) to promote cell viability and maintain phenotype. In this study, we optimized the conditions for human cartilage induction using human adipose–derived stem cells (ASCs), collagen scaffolds, and cyclic HP treatment.

Methods

Human ASCs underwent primary culture and three passages before being seeded into collagen scaffolds. These constructs were incubated for 1 week in an automated bioreactor using cyclic HP at 0–0.5 MPa, 0.5 Hz, and compared to constructs exposed to atmospheric pressure. In both groups, chondrogenic differentiation medium including transforming growth factor-β1 was employed. One, 2, 3, and 4 weeks after incubation, the cell constructs were harvested for histological, immunohistochemical, and gene expression evaluation.

Results

In histological and immunohistochemical analyzes, pericellular and extracellular metachromatic matrix was observed in both groups and increased over 4 weeks, but accumulated at a higher rate in the HP group. Cell number was maintained in the HP group over 4 weeks but decreased after 2 weeks in the atmospheric pressure group. Chondrogenic-specific gene expression of type II and X collagen, aggrecan, and SRY-box9 was increased in the HP group especially after 2 weeks.

Conclusion

Our results demonstrate chondrogenic differentiation of ASCs in a three-dimensional collagen scaffolds with treatment of a cyclic HP. Cyclic HP was effective in enhancing accumulation of extracellular matrix and expression of genes indicative of chondrogenic differentiation.

Introduction

Cartilage is an avascular tissue found in articular surfaces, the tracheobronchial tree, ribs, eyelids, ears, and the nasal skeleton. Tissue-engineered three-dimensional (3D) chondrocyte constructs can be potentially used to repair or replace damaged cartilage. It is widely recognized that chondrocytes, particularly those in articular cartilage, develop and are maintained physiologically by mechanical forces, including hydrostatic pressure (HP)1,2 and shear stress.3,4 These mechanical forces may regulate chondrocyte differentiation, maturation, and tissue formation.5,6 For purposes of tissue engineering, mechanical forces are necessary to develop and maintain cartilage-like constructs in vitro. We reported a high-pressure hydrostatic perfusion culture system that is useful for constructing 3D engineered cartilage using bovine chondrocytes7–9 and human dermal fibroblasts10 with collagen gel/sponge scaffolds.

In this study, we formed 3D cartilage using human adipose–derived stem cells (ASCs) with a collagen scaffold under cyclic HP treatment. To date, ASCs are the most rapidly accessible for harvesting the large quantities of adult stem cells. We have previously reported the extraordinary multipotency inherent in murine ASCs with respect to their ability to undergo chondrogenic,11 osteogenic,11 adipogenic,12 and neurogenic13 differentiation of mouse ASCs in vitro. We have also demonstrated in vivo adipose tissue regeneration14 using mouse ASCs and in vivo periodontal tissue regeneration15 using rat ASCs.

Some reports suggest that ASCs, unlike with bone marrow–derived mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), are not suitable for cartilage regeneration.16,17 These papers addressed the differential expression profile of chondrogenic-specific genes and extracellular matrix in MSCs or ASCs in chondrogenic differentiation. Mehlhorn et al.16 reported that collagen type II and X were secreted more strongly by MSCs than by ASCs in chondrogenic induction using transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1), and Afizah et al.17 reported that collagen type II and proteoglycans were synthesized only in MSCs in chondrogenic induction using TGF-β3.

To test the hypothesis that this perceived limitation of ASCs may be related to the potential necessity of external microenvironmental factors such as HP, this present study was undertaken.

Materials and Methods

Isolation and culture of human ASCs

Under an approval of an IRB protocol, discarded human adipose tissues (∼5 g) harvested from three different donors were used in this study. Adipose tissue was washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) extensively. The fat was finely minced and digested with 0.075% type I collagenase (Worthington Biochemical Corporation, Lakewood, NJ) dissolved in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM)/Hams' F-12 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) with gentle shaking for 30 min at 37°C using a 50 mL conical tube. Then, the digested cell suspension was diluted with an equal volume of growth medium: DMEM/Hams' F-12 (Invitrogen) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% antibiotics–antimicotics (Invitrogen). After centrifugation for 5 min at 390 g, the cell pellet was resuspended with the growth medium and viable cells were counted with Trypan blue. Five hundred thousand cells were seeded to a 100 mm tissue culture dish and incubated in the growth medium at 37°C and 5% CO2. This primary culture was defined as passage 0 (P0). The cells were expanded in the growth medium until 80–90% confluence (approximately 5–7 days in culture), and then underwent three passages (P3).

Characterization of the ASCs

Expression of cell surface protein was evaluated in P3 cells using a FACS Caliber flow cytometer with CELLQuest acquisition software (Becton-Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Data analysis was performed using Flow Jo software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR). About 5 × 105 cells were incubated with saturating concentrations of a fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), phycoerythrin (PE), or allophycocyanine (APC)–conjugated antibodies: CD13, CD14, CD31, CD34, CD44, CD45, and CD90 (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA) for 60 min at 4°C. After incubation, the cells were washed three times with PBS supplemented with 1% FBS. Then, the cells were resuspended in 0.3 mL of cold PBS with 1% FBS for the evaluation.

Construction of collagen scaffolds

Porous collagen sponges were made as previously reported.10 In brief, a solution of 0.5% pepsin-digested collagen from bovine skin: Cellagen (ICN Biomedical, Costa Mesa, CA) was neutralized with HEPES and NaHCO3. Two hundred fifty milliliters of the collagen solution was poured into a mold and frozen at −20°C. Moist tissue paper was placed over the surface of the frozen collagen to avoid formation of a membranous collagen skin during lyophilization. After lyophilization, the tissue paper was removed, and each side of the porous collagen sponge was irradiated by UV light for 3 h at a distance of 30 cm. The final dimensions of the sponge were 7 mm diameter and 1.5 mm thickness. The sponges were placed in a seeding device that was sealed with O-rings.

3D cell culture using a bioprocessor

The P3 cells were harvested and 4.5 × 107 cells were resuspended with 2.5 mL of the cold neutralized type I collagen solution. A 50-μL of the cell suspension (1 × 106 cells) was placed on a sterile Teflon dish (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA), absorbed with the collagen sponge (total 45 sponges), and incubated at 37°C for gelation (Fig. 1). After a day of incubation in the growth medium at 37°C and 5% CO2 in air, five sponges were harvested for samples of day 0. About 40 sponges were divided into two groups: Group HP, incubation during the first 1 week with treatment of cyclic HP at 0–0.5 MPa (3750 mm Hg, 4.93 atm), 0.5 Hz, with a medium replenishment rate of 0.1 mL/min, at 37°C, 3% O2, and 5% CO2 in air using a bioprocessor TEP-P02 (Takagi Industrial, Shizuoka, Japan) followed by no HP for 3 weeks; Group AP, incubation without HP at 37°C, 3% O2, and 5% CO2 for 4 weeks. In both groups, the cells were incubated in a differentiation medium defined as DMEM/Ham's F-12 with 2% FBS and 1% antibiotics–antimycotics, TGF-β (10 ng/mL; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), dexamethasone (1 × 10−7 mol), ascorbic acid 2-phosphate (50 μg/mL), sodium pyruvate 1 mM, and l-proline (40 μg/mL).

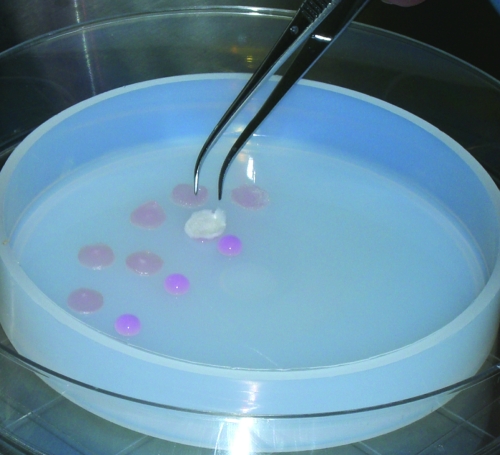

FIG. 1.

Stem sell seeding into the collagen scaffold. Cultured passage 3 adipose–derived stem cells (ASCs) were harvested and resuspended with neutralized type I collagen solution, and each 50 μL of cell suspension (1 × 106 cells) was absorbed with each collagen sponge scaffold and incubated at 37°C for gelation. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/ten.

Histological and immunohistochemical analysis

Constructs were embedded in glycomethacrylate:JB-4 (Polysciences, Warrington, PA) and paraffin, cut into 10-μm sections, and stained with 0.2% toluidine blue-O (Fisher) at pH 4.0. Immunohistological staining was performed using a Vectastatin ABC kit and a 3,38-diaminobenzidine (DAB) kit (Vector Laboratory, Burlingame, CA). About 5 μm paraffin sections were dewaxed with xylene and then rehydrated in a graded series of alcohol to PBS. After rinsing with PBS, the sections were blocked with 3% normal horse serum at room temperature for 20 min in a humidified chamber. For collagen type II staining, the sections were incubated with a rabbit anti-human collagen type II antibody diluted 1:50 (Chemicon, Temecula, CA) with 1% normal horse serum for 60 min at room temperature. After three rinses with PBS, the sections were incubated with biotinylated goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody (Vector Laboratory) and followed by manufacturer's instruction of the ABC kit. Color was developed with DAB. For keratin sulfate staining, the rehydrated sections were incubated for 60 min with biotinylated monoclonal anti-keratan sulfate (Seikagaku Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) in a 1:250 diluted with PBS at room temperature. After three rinses with PBS, color was developed with DAB (Vector Laboratory). Nuclei were counter stained with hematoxylin.

Semiquantitative histological evaluation

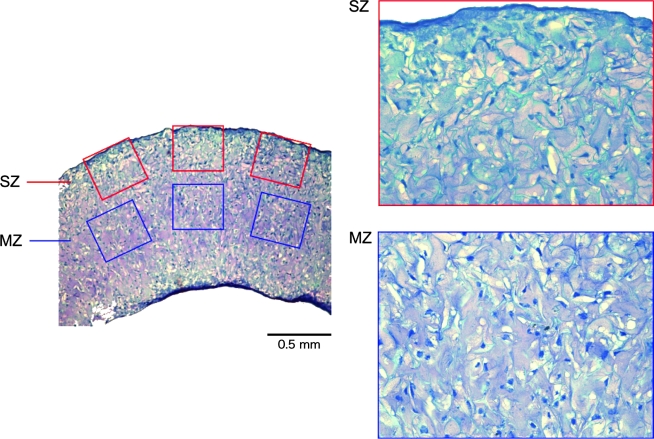

Toluidine blue–stained sections were used for evaluating cellularity in the sponge (Fig. 2). Total number of nuclei on a surface and a deep zone of the sponge were counted. Three fields in each zone of 40 × images were randomly chosen.

FIG. 2.

Semiquantitive histological analysis. Toluidine blue-hematoxylin–stained sections were analyzed for cell proliferation quantification on both surface and middle zone. High-power digital images of sections were used to measure the total number of hematoxylin-positive nuclei. The degree of proliferation was quantified over the entire sponge using three fields in each zone at 40 magnification. SZ, surface zone; MZ, middle zone. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/ten.

Real-time reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction

Freshly collected samples (three sponges in each group at each time point) were washed with PBS and total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Chatsworth, CA) following the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, samples were finely homogenized with handheld homogenizer and QIA shredder with buffer RLT including β-mercaptoethanol. After adding 70% ethanol and mixed well, samples were centrifuged using RNeasy spin column. Then, Buffer RW1 and RPE were sequentially added into the column and centrifuged. Total RNA was extracted with RNase-free water. Total RNA was quantified using the NanoDrop (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE) method.

Complementary deoxyribonucleic acid was synthesized using a SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System for reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR; Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). Total RNA (<1 μg) was mixed with random hexamers (50 ng/μL) and dNTP (10 mM), and then incubated at 65°C for 5 min. Tubes were cooled on ice, and then RT buffer (10 ×), MgCl2 (25 mM), DTT (0.1 M), RNaseOUT (40 U/μL), and SuperScript III RT (200 U/μL) were added, giving a final volume of 21 μL. Samples were then incubated at 25°C for 10 min, 50°C for 50 min, and 85°C for 5 min, and cooled on ice. Then, Escherichia coli RNase H (2 U/μL) was added and incubated at 37°C for 20 min.

Real-time RT-PCR was performed in an ABI Prism7300 system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) using The RT2 SYBR Green/ROX qPCR master mix (SA Biosciences, Frederick, MD) with primers designed for this study (Table 1). Amplifications of the complementary deoxyribonucleic acid samples were performed in triplicate in 96-well plates in a final volume of 20 μL at 40 PCR cycles consisting of a denaturation step at 95°C for 15 s and an anneal/extension step at 60°C for 1 min. Fluorescence measurements were used to generate a dissociation curve utilizing the system software program v1.4 (Applied Biosystems). Relative quantity of each gene was determined from the standard curve. Signal levels were normalized to the expression of a constitutively expressed gene, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), and shown as a relative ratio. We verified the constant GAPDH expression with another internal control gene for 28S ribosomal RNA.

Table 1.

Primers for Real-Time RT-PCR

| Gene | Gene bank code | Forward | Reverse |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type II collagen α-1 (COL2A1) | NM_001844 | 5-CAACACTGCCAACGTCCAGAT-3′ | 5-CTGCTTCGTCCAGATAGGCAAT-3′ |

| Type X collagen (COL10A1) | NM_000493 | 5-TGCTAGTATCCTTGAACTTGGTTCAT-3′ | 5-CTGTGTCTTGGTGTTGGGTAGTG-3′ |

| Aggrecan (ACAN) | NM_001135 | 5-AAGTATCATCAGTCCCAGAATCTAGCA-3′ | 5-CGTGGAATGCAGAGGTGGTT-3′ |

| SRY-box9 (Sox9) | NM_000346 | 5-ACACACAGCTCACTCGACCTTG-3′ | 5-GGAATTCTGGTTGGTCCTCTCTT-3′ |

| Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) | NM_002046 | 5-GAAGGTGAAGGTCGGAGTC-3′ | 5-GAAGATGGTGATGGGATTTC-3′ |

Statistical analysis

All quantitative data reported here were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), with p < 0.05 being considered significantly different. Replicates were done for each experimental group.

Results

Characterization of stem cells

By flow cytometric analysis of cultured cells, the percentage of positive cells (a) for stromal associated markers CD13, 44, and 90 were 98.8 ± 0.6, 95.9 ± 1.4, and 96.4 ± 2.3, respectively; (b) for the macrophage and neutrophilic granulocyte marker CD14 was 0.5 ± 0.2; (c) for the endothelial-associated marker CD31 was 2.6 ± 0.8; (d) for the stem cell–associated marker CD34 was 4.4 ± 0.6; and (e) for the pan-hematopoietic marker CD45 was 0.2 ± 0.1. These results were consistent with a previous report of human ASCs cultured with identical growth media.18 Although primary ASCs are a heterogeneous cell population,18 this heterogeneity decreased after 3P in culture.

Histological and immunohistochemical evaluation

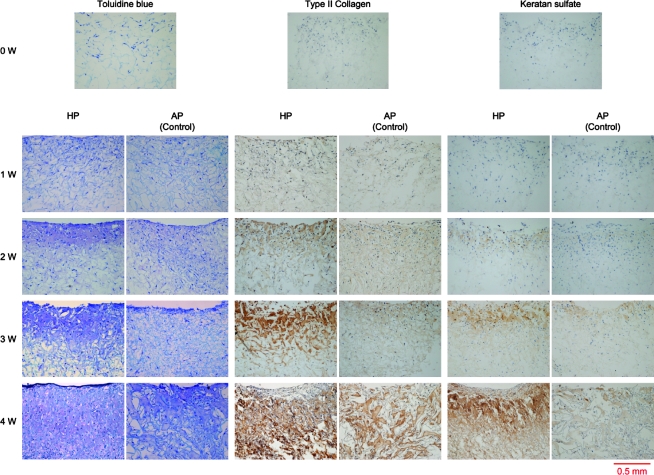

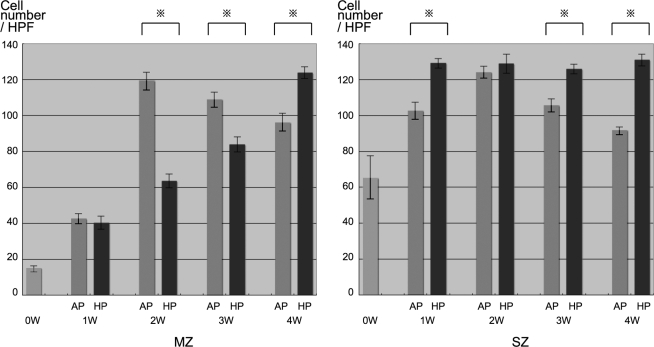

Cells were distributed throughout the sponges. An accumulation of pericellular and extracellular metachromatic matrix stained with toluidine blue was seen in both groups and increased over 4 weeks (Fig. 3). Accumulation of the matrix in the HP group was much denser than AP groups, particularly after 2 weeks. Immunohistochemical evaluation revealed that the production of type II collagen and keratan sulfate in both groups increased with time, with HP groups showing greater production than AP groups at each time point. Cell number in AP groups achieved a peak at 2 weeks of incubation and decreased thereafter on both the middle and surface zone of sponges (Fig. 4). In contrast, cell number in the HP groups increased gradually in the middle zone, and peaked at 1 week after incubation, maintaining their number for the entire course on surface zone.

FIG. 3.

Histological analysis. Accumulation of pericellular and extracellular metachromatic matrix that stained with toluidine blue within collagen scaffolds was observed in both groups and increased over 4 weeks. Accumulation of the matrix in the HP group was much greater than AP groups especially after 2 weeks. Immunohistochemical evaluation revealed that expression of type II and keratan sulfate of both groups increased with time, and HP groups showed greater expression than AP groups at each time point. HP, hydrostatic pressure treated groups; AP, atmospheric pressure control groups. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/ten.

FIG. 4.

Semiquantitative analysis of histology. Cell number in AP groups achieved a peak at 2 weeks of incubation and decreased after peaking on both middle and surface zone of sponges. On the other hand, that of HP groups increased gradually on middle zone, and peaked at a week after incubation and kept their number in the entire course on surface zone. MZ, middle zone; SZ, surface zone; HPF, high-power field (40 × images); AP, atmospheric pressure group; HP, hydrostatic pressure group.

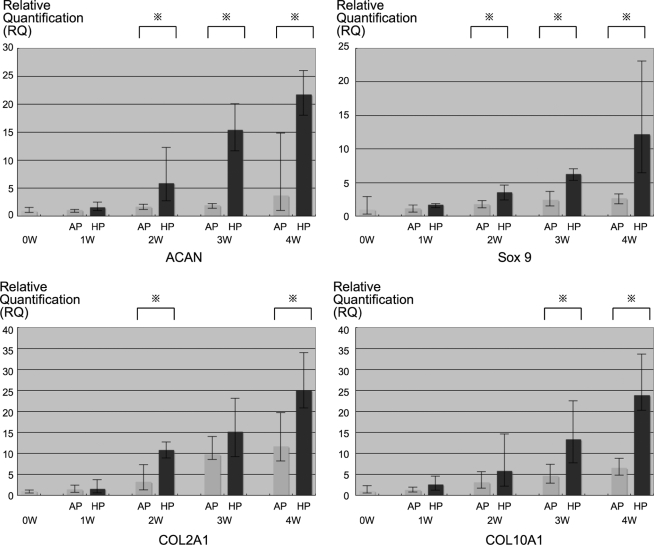

Gene expression evaluation

Gene expression of chondrogenic-specific genes type II collagen α-1 (COL2A1), type X collagen α-1 (COL10A1), aggrecan (ACAN), and SRY-box9 (Sox9) were identified by real-time RT-PCR (Fig. 5) in both groups. However, there existed significant differences between HP and AP groups after 2 weeks of culture for ACAN and Sox9 expression, after 3 weeks of culture for type X collagen, and at the 2 and 4 weeks time points point for type II collagen.

FIG. 5.

Real-time RT-PCR. Three sponges in each group at each time points were analyzed by real-time RT-PCR. Chondrogenic-specific gene expression of type II and X collagen, ACAN, and Sox9 were observed on both groups. However, there was significant differences between HP and AP groups after 2 weeks of culture on ACAN and Sox9, after 3 weeks of culture on type X collagen, and at 2 and 4 weeks of time point on type II collagen. ACAN, aggrecan; Sox9, SRY-box9; COL2A1, type II collagen α-1; COL10A1, type X collagen α-1; AP, atmospheric pressure group; HP, hydrostatic pressure group.

Discussion

ASCs

Adipose tissue represents an alternative source of adult stem cells that also may be harvested from bone marrow,19 skin,20 and skeletal muscles.21 Subcutaneous adipose depots are accessible, abundant, and replenishable.18 Moreover, adipose tissue is routinely discarded after cosmetic surgical procedures such as liposuction, providing a fertile opportunity for adipose tissue banking.22 ASCs previously have been well characterized by many groups.18,23,24 In these studies it has been suggested that over 90% of cultured ASCs express CD13, 44, 73, and 90, but do not express hematopoietic markers CD14 and 45, and our data are consistent with these results. Differences exist, however, among previous studies with regard to CD34 expression by ASCs,18,23,24 and it has been suggested that CD34 detection may be influenced by culture methods and antibodies used for detection. In the present study, CD34 expression was less than 5% at the time point of passage 3 of culture, a finding compatible with the previous results of Mitchell et al.,18 where an identical culture medium was utilized.

The chondrogenic potential of ASCs have been previously demonstrated25,26 although some have indicated that ASCs are less suitable for cartilage regeneration when compared with bone marrow–derived MSCs.16,17,27,28

Hennig et al.28 reported characteristics of chondrogenesis of ASCs. Spheroid-cultured ASCs were supplemented with various human recombinant growth factors, and increased concentrations of TGF-β did not improve chondrogenesis of ASCs, and BMP-6 treatment induced TGF-β-receptor-I expression. Hennig et al.28 speculated that a distinct BMP and TGF-β-receptor repertoire may explain the reduced chondrogenic capacity of ASCs in vitro, which could be compensated by exogenous application of lacking factors.

Effect of HP on chondroinduced stem cells

For tissue engineering applications, modified cell culture systems (e.g., a follow-fiber,29 a spinner flask,30,31 a rotating vessel,32,33 a direct displacement,34,35 and a perfusion culture36–40) have been developed for optimization of culture conditions. Such devices are effective for mass transfer between culture medium and the cell constructs.10 We recently developed a perfusion culture system that promoted osteogenesis,41 hematopoiesis,42 and epithelial formation.43 However, perfusion at a defined flow rate was not consistently beneficial for chondrogenesis by articular chondrocytes in 3D collagen sponge constructs.7 Thus, we developed an HP/perfusion culture system that applied HP directly to the medium fluid phase.44 We confirmed that this bioprocesssor is useful for constructing 3D engineered cartilage using bovine chondrocytes7–9 and human dermal fibroblasts10 with collagen gel/sponge scaffolds.

Comparing chondrogenic gene expression profile by chondroinduced ASCs affected by either AP or HP, type II and X collagen, ACAN, and Sox9 were expressed in both groups. This is considered to relate to the chondrogenic medium, including TGF-β1, that was employed for both groups (HP alone did not have chondrogenic differentiation effects on ASCs; data not shown). However, this expression profile was significantly enhanced by HP loading compared with the AP control group. Sox9 gene expression is crucial for the induction of the cartilage phenotype during skeletal development, and most of the major cartilage matrix proteins, including type II collagen and ACAN, contain binding sites for this transcription factor in their promoters.45 We concluded that HP accelerates chondrogenic differentiation of ASCs and/or maturation of differentiated chondrocytes. Type X collagen is regarded as a hypertrophic chondrocyte marker that is upregulated by mechanical force,45 and our results are compatible with this established function. It has been suggested that type X collagen expression is undesirable for articular cartilage regeneration, because hypertrophic chondrocytes reminiscent of endochondral bone formation.46 Steck et al.46 suggested that type X collagen expression is a common feature induced by protocols for in vitro chondrogenesis, and speculated that it can be prevented by avoiding predifferentiation of stem cells before transplantation in vivo. Further in vivo experiments will be required to confirm this.

The mechanism(s) responsible for the direct effects of HP on cell viability, proliferation, and differentiation of ASCs remains unclear. ASCs may be able to convert a mechanical stimulus into an electrical signals through mechanoreceptors (mechanosensors) such as mechanosensitive ion channels.47 Previously, we attempted to characterize the change in intracellular calcium concentration ([Ca2 + ]i) in response to the application of HP to cultured bovine articular chondrocytes using a fluorescent indicator, a custom-made pressure-proof optical chamber, and laser confocal microscopy.9 The peak [Ca2 + ]i in cells showed a significant increase after the application of HP at constant 0.5 MPa for 5 min, and it was considered that HP stimulates calcium mobilization through stretch-activated ion channels.9 We hope to do future studies to examine the potential influence of mechanosensitive ion channels on chondrodifferentiation of ASCs.

Future prospects of cartilage regeneration using ASCs

In this study, we elucidated that HP followed by static culture promoted production of cartilage-specific extracellular matrix (ECM) by chondroinduced ASCs. For reconstructing cartilage, the desired quality of chondroinduced ASCs should be optimized with mechanophysiological factors, including HP, oxygen concentration, scaffold materials, and medium components, including cytokine and morphogen, for example, BMP-6,28 serum.48 Our study addresses possible options to augment shorted fibrous cartilage. Lineage and histological integration of the chondroinduced ASCs with adjacent cartilage should be studied in vivo.

With respect to the waveform of cyclic HP, we chose a sinusoidal profile between 0 and 0.5 MPa, 0.5 Hz used in the experiments of cultivating bovine chondrocytes7–9 and human dermal fibroblasts.10 We should explore other profiles and algorithms of the HP in vitro to optimize quality of the cell construct, including integration of postimplantation.

The cell location within the scaffold influences diffusion of nutrients and waste products from the perfusion medium associated with more cells proliferating near the periphery than deeper in the scaffold.49–51 The newly proliferated cells and matrix impact the material/structure of the scaffold, nutrient availability, and waste dissipation in the partitioned cell construct. HP/medium perfusion may also be useful for improved mass transfer of necessary medium supply and waste exclusion.

In summary, our results indicate that HP loading using an HP/medium perfusion culture system clearly enhances accumulation of extracellular matrix and expression of chondrogenic-specific genes by ASCs in vitro, potentially obviating previously perceived disadvantages16,17 in cartilage regeneration using ASCs. Combining the latest technologies provides hope that ASCs might be useful for cartilage engineering.

Authors Contribution

Rei Ogawa: Conception and design, collection and/or assembly of data, data analysis and interpretation, and manuscript writing.

Shuichi Mizuno: Provision of study material, and collection and/or assembly of data.

George F. Murphy: Data analysis and interpretation, and manuscript writing.

Dennis P. Orgill: Review of data and manuscript writing.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Parkkinen J.J. Ikonen J. Lammi M.J. Laakkonen J. Tammi M. Helminen H.J. Effects of cyclic hydrostatic pressure on proteoglycan synthesis in cultured chondrocytes and articular cartilage explants. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1993;300:458. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1993.1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lammi M.J. Inkinen R. Parkkinen J.J. Häkkinen T. Jortikka M. Nelimarkka L.O. Järveläinen H.T. Tammi M.I. Expression of reduced amounts of structurally altered aggrecan in articular cartilage chondrocytes exposed to high hydrostatic pressure. Biochem J. 1994;304:723. doi: 10.1042/bj3040723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simon W.H. Mak A. Spirt A. The effect of shear fatigue on bovine articular cartilage. J Orthop Res. 1990;8:86. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100080111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tomatsu T. Imai N. Takeuchi N. Takahashi K. Kimura N. Experimentally produced fractures of articular cartilage and bone. The effects of shear forces on the pig knee. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1992;74:457. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.74B3.1587902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Angele P. Yoo J.U. Smith C. Mansour J. Jepsen K.J. Nerlich M. Johnstone B. Cyclic hydrostatic pressure enhances the chondrogenic phenotype of human mesenchymal progenitor cells differentiated in vitro. J Orthop Res. 2003;21:451. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(02)00230-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Angele P. Schumann D. Angele M. Kinner B. Englert C. Hente R. Füchtmeier B. Nerlich M. Neumann C. Kujat R. Cyclic, mechanical compression enhances chondrogenesis of mesenchymal progenitor cells in tissue engineering scaffolds. Biorheology. 2004;41:335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mizuno S. Allemann F. Glowacki J. Effects of medium perfusion on matrix production by bovine chondrocytes in three-dimensional collagen sponges. J Biomed Mater Res. 2001;56:368. doi: 10.1002/1097-4636(20010905)56:3<368::aid-jbm1105>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mizuno S. Tateishi T. Ushida T. Glowacki J. Hydrostatic fluid pressure enhances matrix synthesis and accumulation by bovine chondrocytes in three-dimensional culture. J Cell Physiol. 2002;193:319. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mizuno S. A novel method for assessing effects of hydrostatic fluid pressure on intracellular calcium: a study with bovine articular chondrocytes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2005;288:C329. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00131.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mizuno S. Watanabe S. Takagi T. Hydrostatic fluid pressure promotes cellularity and proliferation of human dermal fibroblasts in a three-dimensional collagen gel/sponge. Biochem Eng J. 2004;20:203. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ogawa R. Mizuno H. Watanabe A. Migita M. Shimada T. Hyakusoku H. Osteogenic and chondrogenic differentiation by adipose-derived stem cells harvested from GFP transgenic mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;313:871. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ogawa R. Mizuno H. Watanabe A. Migita M. Hyakusoku H. Shimada T. Adipogenic differentiation by adipose-derived stem cells harvested from GFP transgenic mice-including relationship of sex differences. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;319:511. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fujimura J. Ogawa R. Mizuno H. Fukunaga Y. Suzuki H. Neural differentiation of adipose-derived stem cells isolated from GFP transgenic mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;333:116. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.05.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mizuno H. Itoi Y. Kawahara S. Ogawa R. Akaishi S. Hyakusoku H. In vivo adipose tissue regeneration by adipose-derived stromal cells isolated from GFP transgenic mice. Cells Tissues Organs. 2008;187:177. doi: 10.1159/000110805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tobita M. Uysal A.C. Ogawa R. Hyakusoku H. Mizuno H. Periodontal tissue regeneration with adipose-derived stem cells. Tissue Eng Part A. 2008;14:945. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2007.0048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mehlhorn A.T. Niemeyer P. Kaiser S. Finkenzeller G. Stark G.B. Südkamp N.P. Schmal H. Differential expression pattern of extracellular matrix molecules during chondrogenesis of mesenchymal stem cells from bone marrow and adipose tissue. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:2853. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.2853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Afizah H. Yang Z. Hui J.H. Ouyang H.W. Lee E.H. A comparison between the chondrogenic potential of human bone marrow stem cells (BMSCs) and adipose-derived stem cells (ADSCs) taken from the same donors. Tissue Eng. 2007;13:659. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.0118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mitchell J.B. McIntosh K. Zvonic S. Garrett S. Floyd Z.E. Kloster A. Di Halvorsen Y. Storms R.W. Goh B. Kilroy G. Wu X. Gimble J.M. Immunophenotype of human adipose-derived cells: temporal changes in stromal-associated and stem cell-associated markers. Stem Cells. 2006;24:376. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Caplan A.I. Mesenchymal stem cells. J Orthop Res. 1991;9:641. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100090504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones P.H. Harper S. Watt F.M. Stem cell patterning and fate in human epidermis. Cell. 1995;80:83. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90453-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jankowski R.J. Deasy B.M. Huard J. Muscle-derived stem cells. Gene Ther. 2002;9:642. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.D'Andrea F. De Francesco F. Ferraro G.A. Desiderio V. Tirino V. De Rosa A. Papaccio G. Large-scale production of human adipose tissue from stem cells: a new tool for regenerative medicine and tissue banking. Tissue Eng Part C Methods. 2008;14:233. doi: 10.1089/ten.tec.2008.0108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Katz A.J. Tholpady A. Tholpady S.S. Shang H. Ogle R.C. Cell surface and transcriptional characterization of human adipose-derived adherent stromal (hADAS) cells. Stem Cells. 2005;23:412. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yoshimura K. Shigeura T. Matsumoto D. Sato T. Takaki Y. Aiba-Kojima E. Sato K. Inoue K. Nagase T. Koshima I. Gonda K. Characterization of freshly isolated and cultured cells derived from the fatty and fluid portions of liposuction aspirates. J Cell Physiol. 2006;208:64. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guilak F. Awad H.A. Fermor B. Leddy H.A. Gimble J.M. Adipose-derived adult stem cells for cartilage tissue engineering. Biorheology. 2004;41:389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xu Y. Malladi P. Wagner D.R. Longaker M.T. Adipose-derived mesenchymal cells as a potential cell source for skeletal regeneration. Curr Opin Mol Ther. 2005;7:300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sakaguchi Y. Sekiya I. Yagishita K. Muneta T. Comparison of human stem cells derived from various mesenchymal tissues: superiority of synovium as a cell source. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:2521. doi: 10.1002/art.21212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hennig T. Lorenz H. Thiel A. Goetzke K. Dickhut A. Geiger F. Richter W. Reduced chondrogenic potential of adipose tissue derived stromal cells correlates with an altered TGFbeta receptor and BMP profile and is overcome by BMP-6. J Cell Physiol. 2007;211:682. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jauregui H.O. Gann K.L. Mammalian hepatocytes as a foundation for treatment in human liver failure. J Cell Biochem. 1991;45:359. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240450409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vunjak-Novakovic G. Obradovic B. Martin I. Bursac P.M. Langer R. Freed L.E. Dynamic cell seeding of polymer scaffolds for cartilage tissue engineering. Biotechnol Prog. 1998;14:193. doi: 10.1021/bp970120j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sikavitsas V.I. Bancroft G.N. Mikos A.G. Formation of three-dimensional cell/polymer constructs for bone tissue engineering in a spinner flask and a rotating wall vessel bioreactor. J Biomed Mater Res. 2002;62:136. doi: 10.1002/jbm.10150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Freed L.E. Langer R. Martin I. Pellis N.R. Vunjak-Novakovic G. Tissue engineering of cartilage in space. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:1385. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.13885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pei M. Solchaga L.A. Seidel J. Zeng L. Vunjak-Novakovic G. Caplan A.I. Freed L.E. Bioreactors mediate the effectiveness of tissue engineering scaffolds. FASEB J. 2002;16:1691. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0083fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mauck R.L. Soltz M.A. Wang C.C. Wong D.D. Chao P.H. Valhmu W.B. Hung C.T. Ateshian G.A. Functional tissue engineering of articular cartilage through dynamic loading of chondrocyte-seeded agarose gels. J Biomech Eng. 2000;122:252. doi: 10.1115/1.429656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Démarteau O. Jakob M. Schäfer D. Heberer M. Martin I. Development and validation of a bioreactor for physical stimulation of engineered cartilage. Biorheology. 2003;40:331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koller M.R. Emerson S.G. Palsson B.O. Large-scale expansion of human stem and progenitor cells from bone marrow mononuclear cells in continuous perfusion cultures. Blood. 1993;82:378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pazzano D. Mercier K.A. Moran J.M. Fong S.S. DiBiasio D.D. Rulfs J.X. Kohles S.S. Bonassar L.J. Comparison of chondrogenesis in static and perfused bioreactor culture. Biotechnol Prog. 2000;16:893. doi: 10.1021/bp000082v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Redmond E.M. Cahill P.A. Sitzmann J.V. Perfused transcapillary smooth muscle and endothelial cell co-culture—a novel in vitro model. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 1995;31:601. doi: 10.1007/BF02634313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sittinger M. Bujia J. Minuth W.W. Hammer C. Burmester G.R. Engineering of cartilage tissue using bioresorbable polymer carriers in perfusion culture. Biomaterials. 1994;15:451. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(94)90224-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bujía J. Sittinger M. Hammer C. Burmester G. Culture of human cartilage tissue using a perfusion chamber. Laryngorhinootologie. 1994;73:577. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-997199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mueller S.M. Mizuno S. Gerstenfeld L.C. Glowacki J. Medium perfusion enhances osteogenesis by murine osteosarcoma cells in three-dimensional collagen sponges. J Bone Miner Res. 1999;14:2118. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1999.14.12.2118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Glowacki J. Mizuno S. Greenberger J.S. Perfusion enhances functions of bone marrow stromal cells in three-dimensional culture. Cell Transplant. 1998;7:319. doi: 10.1177/096368979800700310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Navarro F.A. Mizuno S. Huertas J.C. Glowacki J. Orgill D.P. Perfusion of medium improves growth of human oral neomucosal tissue constructs. Wound Repair Regen. 2001;9:507. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-475x.2001.00507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mizuno S. Ushida T. Tateishi J. Glowacki J. Effects of physical stimulation on chondrogenesis in vitro. Mater Sci Eng. 1998;C6:301. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wong M. Siegrist M. Goodwin K. Cyclic tensile strain and cyclic hydrostatic pressure differentially regulate expression of hypertrophic markers in primary chondrocytes. Bone. 2003;33:685. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(03)00242-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Steck E. Fischer J. Lorenz H. Gotterbarm T. Jung M. Richter W. Mesenchymal stem cell differentiation in an experimental cartilage defect: restriction of hypertrophy to bone-close neocartilage. Stem Cells Dev. 2008 doi: 10.1089/scd.2008.0213. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gillespie P.G. Walker R.G. Molecular basis of mechanosensory transduction. Nature. 2001;413:194. doi: 10.1038/35093011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kelly T.A. Fisher M.B. Oswald E.S. Tai T. Mauck R.L. Ateshian G.A. Hung C.T. Low-serum media and dynamic deformational loading in tissue engineering of articular cartilage. Ann Biomed Eng. 2008;36:769. doi: 10.1007/s10439-008-9476-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bush P.G. Hall A.C. Regulatory volume decrease (RVD) by isolated and in situ bovine articular chondrocytes. J Cell Physiol. 2001;187:304. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bush P.G. Hall A.C. The osmotic sensitivity of isolated and in situ bovine articular chondrocytes. J Orthop Res. 2001;19:768. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(01)00013-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Simpkin V.L. Murray D.H. Hall A.P. Hall A.C. Bicarbonate-dependent pH(i) regulation by chondrocytes within the superficial zone of bovine articular cartilage. J Cell Physiol. 2007;212:600. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]