Abstract

Objective

Acute Stress Disorder (ASD) and subclinical symptoms of acute stress (SAS) may be a useful framework for understanding the psychological reactions of mothers and fathers of children newly diagnosed with a pediatric malignancy.

Patients and Methods

Mothers (N = 129) and fathers (N = 72) of 138 children newly diagnosed with cancer completed questionnaires assessing acute distress, anxiety, and family functioning. Demographic data were also gathered. Inclusion criteria were: a confirmed diagnosis of a pediatric malignancy in a child under the age of 18 years without prior chronic or life threatening illness and fluency in English or Spanish.

Results

Descriptive statistics and multiple linear regressions were used to examine predictors of SAS. Fifty-one percent (N = 66) of mothers and 40% (N = 29) of fathers met DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for ASD. The majority of the sample reported experiencing at least one SAS. General anxiety, but not family functioning, was a strong predictor of SAS in both mothers and fathers even after controlling for demographic characteristics.

Conclusions

Immediately following their child’s diagnosis of cancer, most mothers and fathers experience SAS, with a subsample meeting criteria for ASD. More anxious parents are at heightened risk of more intense reactions. The findings support the need for evidence-based psychosocial support at diagnosis and throughout treatment for families who are at risk for acute distress reactions.

Keywords: pediatric oncology, acute stress disorder, parents, traumatic stress

INTRODUCTION

The reactions of parents of children with a recent injury or diagnosis of a life-threatening illness are often consistent with traumatic stress responses [1,2,3]. Medically related traumatic stress responses are “a set of psychological and physiological responses to pediatric pain, injury, serious illness, medical procedures, and invasive or frightening treatment experiences” [4] and can include intrusive thoughts about the experience, emotional numbing, physiological arousal and avoidance. Little is known about parents’ acute reactions in response to potentially traumatic medical events.

The life-threatening nature of cancer qualifies the diagnosis as a traumatic event of sufficient magnitude to potentially lead to Acute Stress Disorder (ASD) or Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), as defined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual-Fourth Edition-Text Revision (DSM-IV) [5]. Extensive evidence for long-term traumatic stress responses exists, such as increased incidence and higher rates of posttraumatic stress symptoms (PTSS) and PTSD in parents of childhood cancer survivors relative to controls [6,7]. Mothers and fathers of patients on treatment for cancer also report PTSS [8,6], suggesting that a developmental course of PTSS may be useful in understanding distress and formulating psychosocial treatment options (Supplemental Figure I) [9,10].

ASD can result from actual or threatened death or serious injury to oneself or another person. For the diagnosis of ASD, specific constellations of symptoms must occur within 2–28 days following the traumatic event (Supplemental Table I). Subclinical symptoms of acute stress (SAS) are also possible reactions during this time period. SAS have been observed in parents of children following pediatric traffic injuries, with 83% of parents reporting at least one clinical symptom and 23% reporting at least one symptom in each of the four symptom clusters [2]. Factors related to distress in parents following a hospitalization include (a) race, with fewer White parents reporting acute distress [2] and Black parents appearing to be more at risk for ASD [1]; (b) family functioning (cohesion and expression) [11], (c) anxiety [12], and (d) parents’ previous level of functioning [1,13].

The primary purpose of this study was to examine SAS and ASD in a sample of mothers and fathers of children newly diagnosed with a pediatric malignancy. We evaluated a set of predictors of SAS and explored the relationship between demographic variables and SAS. Based on previous literature [11,12], we hypothesized that poorer family functioning (more conflict and less cohesion) and more general anxiety would predict higher levels of SAS in both mothers and fathers after controlling for parent socioeconomic status, race, and relationship status.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Participants

Mothers (N = 129) and fathers (N = 72) of 138 children under the age of 18 years, newly diagnosed with cancer and without prior chronic or life threatening illness participated.

Procedure

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Newly diagnosed patients were identified at the time of their family meeting when the cancer diagnosis was first discussed in detail with the parents. Families were recruited during the child’s first hospitalization or outpatient appointment (if the child was not admitted). Parents of 158 patients were approached for participation over 15 months, with 141 parents consenting (89% enrollment rate). Three families withdrew, resulting in 138 participating families. Subsequent to providing written informed consent, parents were asked to complete self-report measures. Questionnaires were completed within 1–2 weeks of diagnosis (medianmothers = 4.0 days; M = 7.1, SD = 7.2; medianfathers = 5 days; M = 7.4, SD = 6.8). All measures were available in Spanish and English.

Measures

Demographic Information

Parents provided information regarding their age, relationship status (married/not married), highest level of education completed, and child’s age and race/ethnicity. Patients were categorized as either Caucasian or non-Caucasian, based on self-identified race. The Hollingshead (1975) Four Factor Scale of Social Status, a continuous variable calculated based on parent report of education and occupation, was used to estimate socioeconomic status (SES) [15]. Higher scores indicate higher SES.

Acute Stress Disorder Scale (ASDS)

The primary outcome variable is derived from the ASDS [14], a self-report inventory with 19-items reflecting the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria of ASD (see Supplemental Table I). Parents rated the extent to which they experienced each item since their child’s diagnosis on a 5-point scale (1 = not at all, 5 = very much). Two scores are derived: (a) a diagnosis of acute stress disorder (ASD), indicated by three symptoms of dissociation and one symptom each of re-experiencing, avoidance, and arousal endorsed at ≥3 on the 5-point scale; and (b) a total ASDS score derived by summing the responses across items [1]. Because each ASDS item is a symptom of acute stress (SAS), the total score represents symptom severity. In the present study, total ASDS score and SAS are interchangeable terms. Based on the normative sample, scores ≥56 on the ASDS indicate increased future risk of PTSD. Strong internal consistency has been demonstrated for the total score (α = 0.96) [14].

Family Environment Scale (FES)—Conflict and Cohesion Scales

The FES [16] is a well-established self-report measure of family functioning. The 9-item Conflict and Cohesion subscales use a True–False response format. Higher scores indicate greater conflict and cohesion. Adequate internal consistency has been demonstrated for both the Conflict (α = 0.75) and Cohesion (α = 0.78) scales [16]. Two- and four-month test retest reliability was adequate for both Conflict (r’s = 0.85 and 0.66, respectively) and Cohesion (r’s = 0.86 and 0.72, respectively) scales [13].

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI-Y)—Trait Scale

The STAI-Y [17] is a self-report questionnaire that assesses symptoms of current (state) and general (trait) anxiety. Forty items are rated on 4-point Likert-type scales (1 = not at all, 2 = somewhat, 3 = moderately so, 4 = very much so). Higher scores indicate higher levels of anxiety. Only trait anxiety is used, as dispositional anxiety [17] was of interest. Validity for the trait subscale of the STAI-Y has been documented in general and clinical populations [17], as has the relationship between trait anxiety and traumatic stress outcomes [18]. Internal consistencies for the Trait subscale ranged from 0.89 to 0.96 [17].

Statistical Methods

Frequencies and percentages were used to describe ASD. Means and standard deviations for the total number of endorsed SAS are reported. Phi correlations between binary variables, biserial correlations between dichotomous and continuous variables, and Pearson correlation coefficients between continuous variables were conducted to determine associations among demographic variables, anxiety, family functioning, and SAS. Multiple linear regressions were performed to examine predictors of endorsed SAS (total ASDS score), with separate analyses for mothers and fathers. Covariates were selected based on the literature [1,2,11,12] and preliminary analyses. Race, SES, and relationship status were entered into the first step, and family cohesion, family conflict, and trait anxiety in the second step. The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, Version 13.0 (Chicago, IL) was used.

RESULTS

Demographic and Illness Information

The majority of families (80%) were two caregiver families and parents’ average age was late thirties and early forties (Mmother age = 38.0, SD = 7.3; Mfather age = 41.2, SD = 7.0). Mean Hollingshead score for mothers was 39.06 (SD = 12.22) and for fathers 40.24 (SD = 14.04). On average, the educational level attained by mothers and fathers was some college or a college degree (mothers 41%, N = 53; fathers 54%, N = 39).

The children’s ages ranged from 5 weeks to 18 years (M = 8.2 years, SD = 5.6 years). Fifty-six percent were male (N = 77). Ethnic background was: Caucasian (N = 108, 78.3%), African-American (N = 13, 9.4%), Hispanic (N = 7, 5.1%), Asian (N = 3, 2.2%) and bi-racial (N = 7, 5.0%). Diagnoses were: leukemias (ALL, AML, CML; N = 52, 37.7%), brain tumors (N = 31, 22.5%), lymphomas, (N = 16, 11.6%), neuroblastoma (N = 11, 8.0%), other sarcomas (N = 10, 7.2%), Hodgkin’s Disease (N = 7, 5.1%), Ewing’s sarcomas (N = 4, 2.9%), osteosarcomas (N = 2, 1.4%), germ cell tumors (N = 2, 1.4%), Wilm’s tumor (N = 2, 1.4%), and carcinoma (N = 1, 0.8%).

Acute Stress in Caregivers

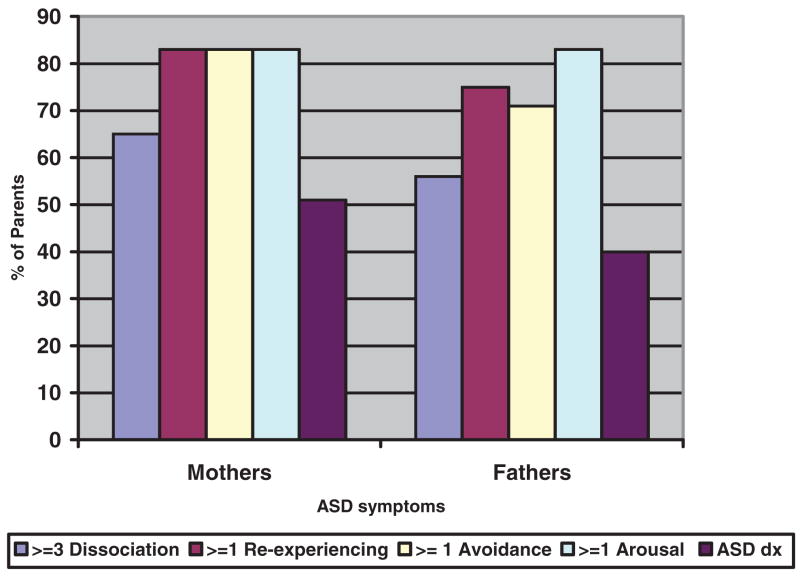

Based on DSM-IV, diagnostic criteria for ASD were met for 51% (N = 66) of mothers and 40% (N = 29) of fathers. A majority of mothers and fathers reported experiencing three or more dissociation symptoms (Nmothers = 84, 65.1%; Nfathers = 40, 55.6%), at least one re-experiencing symptom (N = 107, 82.9%; 54, 75.0%), at least one avoidance symptom (N = 107, 82.9%; 51, 70.8%), or at least one arousal symptom (N = 107, 82.9%; 60, 83.3%). See Figure 1. Out of a possible range of 19 to 95, total ASDS scores ranged from 20 to 94 for mothers (M = 50.2, SD = 16.0; median = 49) and from 21 to 83 for fathers (M = 46.1, SD = 14.8; median = 45). Approximately 36% (N = 47) of mothers and 28% (N = 20) of fathers scored above the clinical cutoff of 56.

Fig. 1.

Endorsed Symptoms (%) of ASD in Mothers and Fathers.

Predictors of SAS

Mothers’ SES (r = 0.17, P <0.05), race (r = 0.18, P <0.05), relationship status (r = 0.24, P <0.01), family conflict (r = 0.34, P <0.001), family cohesion (r = −0.29, P <0.01), and general anxiety (r = 0.63, P <0.001) were correlated with the primary outcome variable, as measured by the total ASDS score (i.e., SAS). Family cohesion (r = −0.27, P <0.01) and conflict (r = 0.40, P <0.01) were also significantly associated with general anxiety for mothers. For fathers, SES (r = −0.22, P <0.05), relationship status (r = 0.26, P <0.05), and general anxiety (r = 0.55, P <0.001) were significantly associated with reported SAS. Paternal reported family cohesion (r = −0.20, P <0.05) and conflict (r = 0.25, P <0.05) were also significantly related to general anxiety.

To examine the predictors of SAS for mothers, a linear regression analysis (Table I) was conducted and revealed that the full model was significant and accounted for 45% (R2 = 0.45, P <0.05) of the variance in SAS, with higher levels of trait anxiety being a statistically significant positive predictor of SAS. Partial r’s were calculated to determine the amount of unique variance in SAS accounted for by predictor variables. Examination of partial correlations with the full model revealed 25% of variance in maternal SAS was accounted for by trait anxiety, with higher anxiety related to higher SAS scores. In contrast, partial correlations for family conflict (partial r = 0.07, P >0.05) and cohesion (partial r = −0.08, P >0.05) were not significant. A separate regression analysis (Table I), with the father data, also revealed that the full model significantly predicted SAS, accounting for 33% (R2 = 0.33, P <0.05) of the variance. Partial correlations revealed paternal trait anxiety accounted for a statistically significant proportion of the variance in SAS (22%). Family conflict (partial r = −0.02, P >0.05) and cohesion (partial r = −0.02, P >0.05) did not account for a significant portion of unique variance in the full model for fathers.

TABLE I.

Linear Regression Analysis Predicting SAS in Mothers and Fathers

| Mothers (N = 120) |

Fathers (N = 68) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables/step | R2Δ | F | β | t | R2Δ | F | β | t |

| Step 1 | 0.08 | 3.50 | 0.10 | 2.31 | ||||

| SES | −0.12 | −1.29 | −0.18 | −1.46 | ||||

| Race | 0.19 | 1.10 | −0.08 | −0.58 | ||||

| Relationship Status | 0.19 | 1.97 | 0.24 | 1.87 | ||||

| Step 2 | 0.37 | 15.36 | 0.23 | 4.89 | ||||

| SES | −0.13 | −1.76 | −0.10 | −0.87 | ||||

| Race | −0.02 | −0.25 | −0.11 | −0.97 | ||||

| Relationship Status | 0.10 | 1.31 | 0.11 | 0.96 | ||||

| Cohesion | −0.09 | −1.15 | −0.02 | −0.18 | ||||

| Conflict | 0.08 | 1.06 | −0.02 | 0.20 | ||||

| Trait Anxiety | 0.56 | 7.16*** | 0.51 | 4.42*** | ||||

Note: SES, socioeconomic status measured by the Hollingshead; Cohesion, Family Environment Scale, Cohesion subscale; Conflict, Family Environment Scale, Conflict subscale; Note: Sample size reduced for linear regression analysis, due to number of mothers and fathers that had all the measures for all the variables that we included in the equation;

P <0.001.

DISCUSSION

Mothers and fathers who have just learned that their child has cancer experience high rates of acute stress symptoms, with over half of the mothers and 40% of fathers meeting diagnostic criteria for ASD in the first 2 weeks after diagnosis. The presence of SAS, especially avoidance, arousal and re-experiencing of events related to their child’s diagnosis, are reported by nearly all parents. Previous findings report similar parental rates of SAS in response to their child’s hospital admission following a pediatric traffic injury [2] and in parents of children and infants admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) [1]. The pervasiveness of SAS at this time indicates that they represent a normative response to the events surrounding a child’s illness and early diagnosis and treatment phases. Indeed, previous studies show the majority of families will recover from their traumatic stress responses and access their natural coping resources to adjust to their child’s illness and treatment [2,19]. These data are supportive of a model of medically related traumatic stress responses [10] and are the first empirical report of acute stress symptoms in this population. The data also support the impact of the child’s illness on fathers [20].

Parents who are more generally anxious (e.g., prior to child’s illness) are more likely to experience SAS than less anxious parents. Having a generally anxious style was associated with SAS even after accounting for parents’ SES, relationship status, and race. Mothers and fathers remain at risk for psychological difficulties across time, particularly when they are prone towards anxiety in general. Dispositional anxiety has previously been shown to predict PTSS in both mothers and fathers of survivors of childhood cancer [18]. It is possible that parents who experience more anxiety in general have fewer resources at their disposal to initially manage distressing events such as the diagnosis of cancer in their child. Initial SAS may also have long-term implications. In a group of parents with a child admitted to the PICU, parental ASD at the time of admission was related to later PTSD, with over 70% of parents with ASD having PTSD 2 months after their child’s discharge [1].

The data are supportive of the recommendations made by national and international groups for the inclusion of mental health professionals on pediatric oncology treatment teams in terms of intervention [21]. Intervention programs, such as Surviving Cancer Competently Intervention Program-Newly Diagnosed [22] and maternal problem solving skills training (PSST) [23] have been designed to assist families during the initial months of diagnosis and treatment. As noted by Sahler et al., [23] it is possible that the effect of PSSTon emotional distress is associated with reductions in future PTSS. Resources are also available to help pediatricians and nursing staff refine “trauma-informed practice.” For example, the Medical Traumatic Stress Toolkit [24] provides materials that can augment practice to include brief assessment of risk factors for ongoing distress and include materials to be provided directly to parents and patients.

Limitations of the current study should be considered when interpreting these findings. Most significantly, the data are cross-sectional in nature; we cannot speak to the directionality between general anxiety and SAS. In addition, the study sample was relatively homogeneous in nature. However, it should be noted that the sample reflected the clinic population from which the sample was drawn. Still, additional studies, with more diverse populations will be needed to assess the generalizability of these findings. Finally, anxiety symptoms and SAS were provided by the same reporter potentially increasing the covariance between these variables.

Given that many mothers and fathers are suffering acutely following their child’s diagnosis, the delivery of psychosocial support at diagnosis remains critically important. At the same time, efficient provision of such care may be informed by the results of this study as well. Identifying parents with higher levels of dispositional anxiety, who are at higher risk of meeting criteria for a diagnosis of ASD from those who have less anxious personalities, would help target parents and facilitate appropriate interventions for this group of affected individuals.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the participating families and our research assistants, J. J. Cutuli and Ivy Pete.

Grant sponsor: The National Cancer Institute; Grant number: CA 98039.

Abbreviations

- ASD

acute stress disorder

- SAS

symptoms of acute stress

- PTSD

posttraumatic stress disorder

- PTSS

posttraumatic stress symptoms

- PTE

potentially traumatic events

- DSM-IV-TR

diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders-fourth edition-text revision

- ASDS

acute stress disorder scale

- STAI

state trait anxiety inventory

- FES

family environment scale

- SES

socioeconomic status

- PSST

problem solving skills training

Footnotes

This article contains Supplementary Material available at http://www.interscience.wiley.com/jpages/1545-5009/suppmat.

References

- 1.Balluffi A, Kassam-Adams N, Kazak A, et al. Traumatic stress in parents of children admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2004;5:547–553. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000137354.19807.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Winston FK, Kassam-Adams N. Acute stress disorder symptoms in children and their parents after pediatric traffic injury. Pediatrics. 2002;109:1–7. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.6.e90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Phipps S, Long A, Hudson M, et al. Symptoms of posttraumatic stress in children with cancer and their parents: Effects of informant and time from diagnosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2005;45:952–959. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Child Traumatic Stress Network. Definition of medical traumatic stress. Medical Traumatic Stress Working Group meeting; Philadelphia, PA. September, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders—Fourth Edition, Text Revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kazak AE, Alderfer M, Rourke MT, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and posttraumatic stress symptoms (PTSS) in families of adolescent childhood cancer survivors. J Ped Psychol. 2004;29:211–219. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsh022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barakat LP, Kazak AE, Meadows AT, et al. Families surviving childhood cancer. A comparison of posttraumatic stress symptoms with families of healthy children. J Ped Psychol. 1997;22:843–859. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/22.6.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kazak AE, Boeving CA, Alderfer M, et al. Posttraumatic stress symptoms during treatment in parents of children with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:7405–7410. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.09.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barrera M, D’Agnostino NM, Gibson J, et al. Predictors and mediators of psychological adjustment in mothers of children newly diagnosed with cancer. Psycho-Oncol. 2004;13:630–641. doi: 10.1002/pon.765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kazak AE, Kassam-Adams N, Schneider S, et al. An integrative model of pediatric medical traumatic stress. J Ped Psychol. 2006;31:343–355. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsj054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sloper P. Predictors of distress of children with cancer: A prospective study. J Pediatr Psychol. 2000:79–91. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/25.2.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Board R, Ryan-Wenger N. Stressors and stress symptoms of mothers with children in the PICU. J Ped Nursing. 2003;18:195–202. doi: 10.1053/jpdn.2003.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Auerbach SM, Kiesler DJ, Wartella J, et al. Optimism, satisfaction with needs met, interpersonal perceptions of the healthcare team, and emotional distress in patients’ family members during critical care hospitalizations. Am J Critical Care. 2005;14:202–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bryant RA, Moulds ML, Guthrie RM. Acute Stress Disorder Scale: A self-report measure of acute stress disorder. Psychol Assessment. 2000;12:61–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hollingshead A. The Four-Factor Index of Social Position. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moos RH, Moos BS. Family environment scale. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spielberger C. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Anxiety Inventory (Form Y) (“Self-Evaluation Questionnaire”) Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kazak AE, Stuber ML, Barakat LP, et al. Predicting posttraumatic stress symptoms in mothers and fathers of childhood cancers. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37:823–831. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199808000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kazak AE, Cant C, Jensen MM, et al. Identifying psychosocial risk indicative of subsequent resource use in families of newly diagnosed pediatric oncology patients. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3220–3225. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.12.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garfield CF, Isacco A. Fathers and the well-child visit. Pediatrics. 2006;117:e637–e645. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.American Academy of Pediatrics: Policy Statement. Guidelines for Pediatric Cancer Centers. Pediatrics. 2004;113:1833–1835. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.6.1833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kazak A, Simms S, Alderfer M, et al. Feasibility and preliminary outcomes from a pilot study of a brief psychological intervention for families of children newly diagnosed with cancer. J Pediatr Psychol. 2005;30:644–655. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsi051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sahler OJZ, Fairclough DL, Phipps S, et al. Using problem-solving skills training to reduce negative affectivity in mothers of children with newly diagnosed cancer: Report of a multisite randomized trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73:272–283. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.2.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stuber M, Schneider S, Kassam-Adams N, et al. The medical traumatic stress toolkit. CNS Spectrums. 2006;11:1–6. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900010671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]