Abstract

Objective

To identify factors associated with high antenatal psychosocial stress and describe the course of psychosocial stress during pregnancy.

Study Design

We performed a cross-sectional analysis of data from an ongoing registry. Study participants were 1,522 women receiving prenatal care at a university obstetrical clinic from January 2004 through March 2008. Multiple logistic regression identified factors associated with high stress as measured by the Prenatal Psychosocial Profile stress scale.

Results

The majority of participant reported antenatal psychosocial stress (78% low-moderate, 6% high). Depression [OR 9.6(5.5–17.0)], panic disorder [OR 6.8(2.9–16.2)], drug use [OR 3.8(1.2–12.5)], domestic violence [OR 3.3(1.4–8.3)], and having ≥ 2 medical comorbidities [OR 3.1(1.8–5.5)] were significantly associated with high psychosocial stress. For women who screened twice during pregnancy, mean stress scores declined during pregnancy [(14.8±3.9 versus 14.2±3.8; (p<0.001)].

Conclusions

Antenatal psychosocial stress is common, and high levels are associated with maternal factors known to contribute to poor pregnancy outcomes.

Keywords: Psychosocial stress, antenatal screening, pregnancy

Introduction

Psychosocial stress in pregnancy, defined as “the imbalance that a pregnant woman feels when she cannot cope with demands…which is expressed both behaviorally and physiologically” 1, has not routinely been measured in everyday obstetric practice. It has recently come to the forefront of policy, however, with The American College of Obstetricians & Gynecologists (ACOG) releasing a 2006 committee opinion stating that psychosocial stress may predict a woman’s “attentiveness to personal health matters, her use of prenatal services, and the health status of her offspring”. 2 In this committee opinion, ACOG advocated screening all women for psychosocial stress and other psychosocial issues during each trimester of pregnancy and the postpartum period. 2

Despite these recommendations the prevalence of antenatal psychosocial stress is unclear 3 and its influence on maternal health is likely underestimated. Further, little research exists regarding which factors contribute to or coexist with psychosocial stress during pregnancy. In the few studies conducted to date, associations have been noted between antenatal psychosocial stress and domestic violence 4–8, substance use 9, 10, depressive symptoms 11–13, psychiatric diagnoses 14, poor weight gain 10, and having a chronic medical disorder. 10 Many of these studies were limited, however, in their sample size, select populations, or assessment of potential covariates (e.g. use of non-validated measures or medical records only). Some of these identified factors are known to be associated with adverse birth outcomes (e.g. preterm delivery 15–17, low birth weight 16–18), so determining their associations with psychosocial stress is paramount.

Research regarding the factors associated with high psychosocial stress during pregnancy has potential to provide targets for interventions, leading to an increase in maternal well-being and a potential decrease in adverse birth outcomes. The primary aims of this study were to identify factors associated with high antenatal psychosocial stress and describe the course of psychosocial stress during pregnancy.

Materials and Methods

Design/Sample/Setting/Timeframe

We studied pregnant women enrolled in a longitudinal study of antenatal care at a single university obstetrical clinic. The clinic serves a group of women with diversity in race, socio-economic status (SES), and medical risk, with a payer mix of 46.5% private insurance, 51.6% Medicaid, and 1.9% self-pay. 19 Clinic providers include attending physicians, fellows, residents, and midwives. As part of a psychosocial screening program, questionnaires measuring stress and mood were introduced in January 2004. Questionnaires were designed to be distributed by clinical staff as part of routine clinical care to all women at least once during pregnancy with the goal of 2 times; first during the early 2nd trimester and again in the 3rd trimester. All women receiving ongoing obstetrical care and completing at least one questionnaire from January 2004 through March 2008 were eligible for inclusion in the study. Exclusion criteria included age less than 15 years at the time of delivery and inability to complete the clinical questionnaire due to mental incapacitation or language difficulties (i.e., no interpreter available). Clinical staff were asked to contact and consent potentially eligible subjects at the time of screen completion. All procedures were approved by the University of Washington’s Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Data were collected from self-report questionnaires and from automated medical records. The questionnaire included inquiry regarding demographic characteristics, social history, medication use, general health history, past obstetrical complications, as well as validated measures assessing psychosocial stress 20, 21, depression and panic disorder 14, 22, tobacco use 23, alcohol use 24, drug use 25, and domestic violence. 26 Maternal age and parity were obtained from the automated medical record.

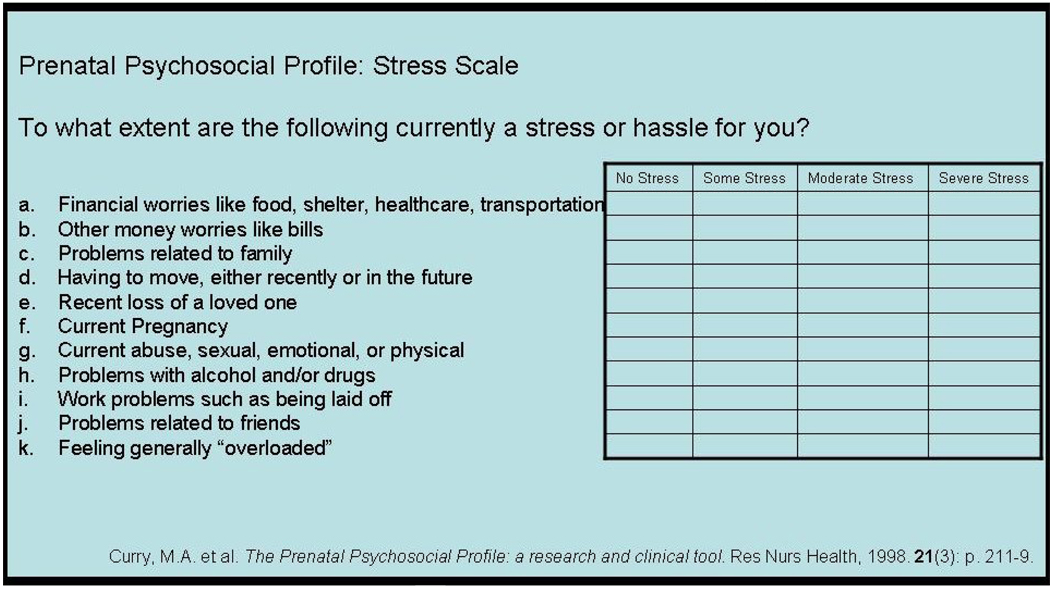

Psychosocial stress was measured using the Prenatal Psychosocial Profile stress scale, which has been validated for use in pregnant populations. 20, 21 It is an 11 question survey using a Likert response scale with possible scores ranging between 11 and 44 (see Appendix). The scale’s validity and reliability have been supported among ethnically diverse rural and urban pregnant women. 20 Several recent studies have used this instrument to measure psychosocial stress. 4, 5, 8, 9, 11, 27–29 In these studies, mean stress scores ranged from 17 to 23. 4, 5, 9, 11, 21, 29 The recommended cut-off for high stress depends upon the population studied and the patient characteristics; there are no recommendations for differentiating low to moderate stress. In the two studies that have established cut-offs for high stress, one used scores above the mean plus 2 standard deviations (score >26) 5 while another chose a set percentile of 25% (score ≥ 23) 28. Both of theses studies had predominantly low SES participants. In our heterogeneous SES population, we chose a cut-off of scores above the mean plus 2 standard deviations – corresponding to a score of ≥ 23 for our sample.

APPENDIX.

Depression and panic disorder were assessed using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) short form (15-items), which yields diagnoses for major depression, minor depression, and panic disorder. In a study of 3,000 OB/GYN patients, high sensitivity (73%) and specificity (98%) for the depression items were demonstrated for a diagnosis of major depression based on the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID). 14, 22 This was also true for diagnostic items related to panic disorder (sensitivity 81%, specificity 99%). 22 In our study, women meeting DSM-IV criteria for major or minor depression on the PHQ-9 were classified as experiencing current depression. The criteria for major depression require the subject to have, for at least two weeks, five or more depressive symptoms present for more than half the days, with at least one of these symptoms being depressed mood or anhedonia. 14 The criteria for minor depression require the subject to have, for at least two weeks, two to four depressive symptoms present for more than half the days, with at least one of these symptoms being depressed mood or anhedonia. 14 Women were classified as having current panic disorder if they answered “yes” to five diagnostic criteria for panic disorder.

Tobacco, alcohol, and drug use were assessed using the Smoke-Free Families Prenatal Screen 23, the Alcohol T-ACE 24, and the Drug CAGE 25. The Smoke-Free Families Prenatal Screen was specifically developed to maximize disclosure of smoking status during pregnancy and any current smoking is classified as tobacco use. 23 Both the T-ACE and the Drug CAGE assess substance use during the current pregnancy as well as in the 12 months prior to pregnancy to identify all women at risk for use. The T-ACE was developed to identify at risk drinkers, has been validated in a pregnant population, and has increased sensitivity compared to the Alcohol CAGE. 24 Sensitivity and specificity of identifying at risk drinkers are 69% and 89% when a score of ≥ 2 on the T-ACE is used. 24 The Drug CAGE, developed from the original CAGE to identify problem illicit drug use, has been validated in pregnant women with a cut-off score of ≥ 3 identifying problem drug use. 25 In this study, women were considered as at risk drinkers or problem drug users if they met criteria for risk drinking or problem drug use during pregnancy and/or in the 12 months prior to pregnancy.

The 3-question Abuse Assessment Screen 26 assesses physical and sexual violence during the past year and during pregnancy. This screen has been used both as a clinical screening tool with established validity and test-retest reliability, and for research purposes as a dichotomous measure of abuse. 4, 5, 8, 18, 30 Consistent with previous research studies, we classified women as positive for domestic violence if they answered “yes” to any of the three abuse questions.

Women were considered as having high medical comorbidity if they self reported ≥ 2 chronic medical problems outside of pregnancy (e.g., asthma, hypertension, diabetes, or cardiovascular problems). A history of pregnancy complications was recorded for patients who self reported one or more significant pregnancy complications (e.g., gestational diabetes, pre-eclampsia, eclampsia, preterm delivery, or placental abruption) in a prior pregnancy. Other demographics including employment, education, and marital status were dichotomized as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Maternal Demographic, Behavioral, and Clinical Characteristics by Psychosocial Stress Category

| Characteristic | Total (n=1,522) |

High Stress |

Test Statistic (t or χ2) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n=91) |

No (n=1,421) |

||||

| Age (years) | 30.4 (±6.3) | 28.0 (±6.6) | 30.6 (±6.3) | 3.676 | <0.001 |

| Gestational Age1 (wks) | 23.5 (±7.3) | 25.0 (±7.5) | 23.4 (±7.3) | 1.917 | 0.058 |

| Education | 36.433 | <0.001 | |||

| • ≤ High School | 19.3% (n=293) | 42.9% (n=39) | 17.9%(n=254) | ||

| • > High School | 73.5%(n=1,118) | 48.4% (n=44) | 75.1%(n=1,067) | ||

| Employment | 39.171 | <0.001 | |||

| • Unemployed | 11.1% (n=169) | 30.8% (n=28) | 9.9% (n=141) | ||

| • Other2 | 81.5% (n=1,241) | 60.4% (n=55) | 83.0%(n=1,179) | ||

| Marital Status | 43.522 | <0.001 | |||

| • Married/Partnered | 81.1% (n=1,234) | 58.2% (n=53) | 82.6%(n=1,174) | ||

| • Other3 | 11.8% (n=179) | 33.0% (n=30) | 10.5% (n=149) | ||

| Race | 26.075 | <0.001 | |||

| • White | 66.9% n=1,018) | 56.0% (n=51) | 67.6% (n=961) | ||

| • Black | 7.6% (n=116) | 14.3% (n=13) | 7.2% (n=102) | ||

| • American Indian or Native Alaskan | 2.2% (n=34) | 4.4% (n=4) | 2.1% (n=30) | ||

| • Asian | 10.9% (n=166) | 6.6% (n=6) | 11.2% (n=159) | ||

| • Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 1.2% (n=18) | 1.1% (n=1) | 1.1% (n=16) | ||

| • Mixed | 5.5% (n=83) | 14.3% (n=13) | 4.9% (n=69) | ||

| • Undeclared | 5.7% (n=87) | 3.3% (n=3) | 5.9% (n=84) | ||

| Ethnicity | 2.302 | 0.316 | |||

| • Hispanic | 9.0% (n=137) | 8.8% (n=8) | 9.1% (n=129) | ||

| • Non-Hispanic | 81.1% (n=1,234) | 76.9% (n=70) | 81.5%(n=1,158) | ||

| • Undeclared | 9.9% (n=151) | 14.3% (n=13) | 9.4% (n=134) | ||

| Parity | 0.756 | 0.385 | |||

| • Primiparous | 53.7% (n=818) | 58.2% (n=53) | 53.6% (n=761) | ||

| • Multiparous | 46.3% (n=704) | 41.8% (n=38) | 46.4% (n=660) | ||

| Current Cigarette Smoking | 75.808 | <0.001 | |||

| • No | 88.8% (n=1,352) | 67.0% (n=61) | 90.6%(n=1,288) | ||

| • Yes | 7.4% (n=112) | 30.8% (n=28) | 5.9% (n=84) | ||

| Alcohol Use | 1.147 | 0.284 | |||

| • No | 80.7% n=1,228) | 80.2% (n=73) | 85.0%(n=1,208) | ||

| • Yes | 14.9% (n=212) | 17.6% (n=16) | 13.7% (n=195) | ||

| Drug Use | 45.139 | <0.001 | |||

| • No | 95.9% (n=1,460) | 87.9% (n=80) | 96.6%(n=1,372) | ||

| • Yes | 1.6% (n=23) | 9.9% (n=9) | 1.0% (n=14) | ||

| Domestic Violence | 73.017 | <0.001 | |||

| • No | 95.4% (n=1,452) | 80.2% (n=73) | 96.6%(n=1,372) | ||

| • Yes | 3.5% (n=54) | 19.8% (n=18) | 2.5% (n=36) | ||

| Current Depression (Major or Minor) | 221.765 | <0.001 | |||

| • No | 90.7% (n=1,381) | 47.3% (n=43) | 93.5%(n=1,329) | ||

| • Yes | 9.1% (n=138) | 52.7% (n=48) | 6.3% (n=90) | ||

| Panic Disorder | 101.189 | <0.001 | |||

| • No | 96.6% (n=1,470) | 79.1% (n=72) | 97.7%(n=1,389) | ||

| • Yes | 3.1% (n=47) | 20.9% (n=19) | 2.0% (n=28) | ||

| ≥ 2 Chronic Health Problems | 51.307 | <0.001 | |||

| • No | 74.8% (n=1,139) | 45.1% (n=41) | 76.8%(n=1,091) | ||

| • Yes | 18.9% (n=287) | 46.2% (n=42) | 17.0% (n=242) | ||

| History of Pregnancy Complications | 2.727 | 0.099 | |||

| • No | 64.7% (n=984) | 56.0% (n=51) | 65.2% (n=927) | ||

| • Yes | 32.3% (n=492) | 39.6% (n=36) | 31.8% (n=452) | ||

Gestational age at 1st screening

Other includes employed, homemaker, retired, or student

Other includes single and not living with partner, separated or divorced, widowed

Analysis

Univariate analysis was performed for the sample characteristics by stress level (high stress versus other, χ2 test for categorical variables and T-test for continuous variables, significance at p < 0.05). Significant variables from the univariate analysis and variables established a priori were entered into a multiple logistic regression model to determine associations with high psychosocial stress. Variables were added to the model one by one and were excluded from the final model if they did not improve the overall model fit. For women who completed screening at two time points, their mean stress scores were compared using a paired T-test.

Questionnaire data for each subject was entered and stored using Filemaker Pro (FilemakerPro Version 9 for Windows ©1994–2008, Santa Clara, California: FileMaker, Inc). Data was analyzed using SPSS (SPSS for Windows, Rel. 15.0.1. 2001. Chicago: SPSS Inc.).

Results

During the study period 2,046 women completed at least one psychosocial screen as part of their routine antenatal care. All women completing a screen were eligible for the study. Staff were present in clinic to contact around 80% (n=1,639). Of 1,639 women whom staff were able to contact for involvement in the study, 92.9% (n=1,522) consented for participation while 7.1% (n=117) declined.

Among the 1,522 study participants, mean age was 30.4 ± 6.3 years, with a range of 15–51 years. Racial identification was 66.9% White, 10.9% Asian, 7.6% Black, 2.2% American Indian or Alaska Native, 1.2% Pacific Islander, 5.5% mixed race, and 5.7% undeclared. Ethnicity was nine percent Hispanic. The index pregnancy was the first pregnancy for 53.7% (n=818). The majority of women reported living with a spouse or partner (87.3%, n=1,234) and had achieved education beyond high school (79.2%, n=1,118). Twelve percent (n=169) reported that they were unemployed. All other maternal demographic, behavioral, and clinical characteristics are reported in Table 1.

Six percent (n=91) of women reported high stress, 78% (n=1,190) reported low/moderate stress, and 16% (n=241) reported no stress. The mean gestational age at first screening was 23.5 ± 7.3 weeks and mean stress score was 15.0 ± 4.0. Forty-three percent (n=658) of the enrolled women completed screening at two time points during pregnancy. For this subset, mean gestational age at 1st screening was 22.1 ± 6.0 weeks with mean stress score of 14.8 ± 3.9; and mean gestational age at 2nd screening was 36.3 ± 1.8 weeks with mean stress score 14.2 ± 3.8. A statistically significant difference in mean stress scores from 1st to 2nd screening was found (P < 0.001).

Adjusted odds ratios from the logistic regression examining the relationship between maternal characteristics and high psychosocial stress are shown in Table 2. Five maternal characteristics were significantly associated with high psychosocial stress. Domestic violence, drug use, and having two or more medical problems increased the odds of high psychosocial stress during pregnancy by 3 to 4 fold, while current depression and panic disorder increased the odds by 7 to 10 fold. Conversely, marital status, employment, education, race, age, and history of pregnancy complication were not significantly associated with high psychosocial stress in the final model.

Table 2.

Adjusted Odds of High Psychosocial Stress during Pregnancy

| Maternal Characteristic | Adjusted Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|

| Current depression1 | 9.6 | (5.5, 17.0) |

| Panic disorder | 6.8 | (2.9, 16.2) |

| Drug use | 3.8 | (1.2. 12.5) |

| Chronic health problems (≥2) | 3.1 | (1.8, 5.5) |

| Domestic violence | 3.3 | (1.4, 8.3) |

| Not married/partnered | 1.6 | (0.8, 3.2) |

| Unemployed | 1.7 | (0.9, 3.3) |

| ≤ High school | 1.1 | (0.6, 2.2) |

| Race | ||

| White | 1.0 | Reference |

| Black | 1.3 | (0.5, 3.1) |

| Asian | 1.1 | (0.4, 2.9) |

| Other2 | 1.1 | (0.6, 2.3) |

| History of pregnancy complications | 1.2 | (0.7, 2.1) |

| Maternal age | 1.0 | (1.0, 1.0) |

Major or minor depression

Other category includes American Indian, Pacific Islander, Mixed, Undeclared

Comment

In a population of ethnically and economically diverse pregnant women attending a university-based prenatal clinic, antenatal psychosocial stress was common, with slightly higher mean levels earlier in pregnancy. High levels of antenatal psychosocial stress were significantly associated with depression, panic disorder, drug use, domestic violence, and having two or more medical comorbidities. Our study adds significantly to a small body of literature regarding factors associated with antenatal stress.4–14 It firmly establishes an independent association between current psychiatric mood disorders (major/minor depression, panic disorder) and high antenatal psychosocial stress. It improves upon prior studies showing a relationship between depressive symptoms or psychiatric disorders and increased stress during pregnancy 11–14, by using diagnostic criteria and assessing for multiple potential confounders. For substance use, we found psychosocial stress to be associated with risky drug use, but not alcohol use. Two previous studies have linked substance use with high psychosocial stress 9, 10, but these studies were limited in that one combined alcohol and drug use in a single variable and the other used medical records to determine substance use during pregnancy. Our results are distinctive in that we measured alcohol use and drug use individually with separate, validated measures. The strong independent association between domestic violence and antenatal stress found in our study strengthens the conclusion of prior studies. 4–8 We further found that chronic medical problems are independently associated with high antenatal psychosocial stress. Our findings did not show a significant independent association between antenatal psychosocial stress and several maternal characteristics seen in prior studies ( i.e., race 7, 31, 32, marital status 31, age 7, education 7, poverty 7, 32, and cigarette smoking 33–35).

Levels of psychosocial stress likely change throughout the course of pregnancy, although few studies have measured psychosocial stress at different antenatal time points. 3, 21, 36–38 Our study found a significant decrease in mean stress scores from first to second screening, consistent with the findings of several prior studies. 20, 21, 36, 37 Although statistically significant, the decrease in the actual score was small and whether this is clinically significant merits further investigation. In contrast to this observed decline in antenatal stress shown in ours and other studies, higher rates of low birthweight and preterm delivery have been noted in studies where levels of antenatal stress rose during pregnancy. 3, 36, 37 Thus, not only the level of stress but the time point in pregnancy during which high maternal stress is experienced may be influential in regard to risk of adverse outcomes.

Our study has a number of strengths, including utilization of a routine screening protocol with high level of subject participation, large sample size, use of accurate measurement of multiple covariates, and adjustment for biomedical, demographic, psychosocial, and behavioral factors in our models. Among prior studies, our study is unique in accurately assessing a large number of potential confounders to establish a more complete model for antenatal psychosocial stress. We are limited, however, by the use of cross-sectional data, allowing assessment of associations but not causality or temporal sequence between specific factors and high psychosocial stress. In addition, only a subset of the sample completed two screens during pregnancy, limiting the amount of information obtained regarding the change in stress during pregnancy. Lastly, the majority of the data were self-reported, which may lead to underreporting of sensitive behaviors.

Depression 17, panic disorder 17, domestic violence 15, 18, drug use 16, and having medical comorbidities 39, 40 are all known to be individually associated with poor obstetrical outcomes. Antenatal psychosocial stress contributes to maternal distress and may also be associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes (e.g. LBW 3, 10, 41–44, PTD 3, 28, 37, 41, 45, 46). The relationship of the above maternal factors with psychosocial stress and the way in which they lead to adverse outcomes is unknown, but may occur via indirect behavioral and direct physiologic pathways. 47, 48 Behavioral responses to stress may include alterations in nutrition, sleep, exercise, substance use, tobacco use, and/or use of prenatal services. 10, 47 While physiological responses to psychosocial stress may include both neuroendocrine and immune responses. 47, 49

Identification of pregnant women experiencing significant psychosocial stress presents health care providers an opportunity to further assess the nature of the stress and alerts them to assess for associated risk factors. Decreasing high antenatal psychosocial stress in itself will improve maternal well-being. Although many of the factors associated with stress are difficult to overcome (e.g., poverty, racism, lifetime exposure to violence) 27, success may be found in specific health behavior interventions designed to reduce stress (e.g., nutritional counseling, physical and mental relaxation, education, and social support). 50 Poor health behaviors and stress often coexist and predate pregnancy, so it can be argued that interventions should be introduced across a woman’s reproductive lifespan (preconception, perinatal, and internatal). 47, 50, 51 Decreasing high stress and/or addressing associated risk factors may also decrease the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes. The screening protocol applied in this study is a model for screening in a prenatal clinic 19, identifying not only women experiencing stress, but also those with depression, panic disorder, substance use, and domestic violence. With identification of these other factors, health care providers are provided additional specific foci for intervention.

In conclusion, antenatal psychosocial stress during pregnancy is common, and high stress is associated with multiple maternal factors that are known to contribute to poor pregnancy outcomes. Our findings lend support to recent ACOG recommendations to screen for psychosocial stress during pregnancy. 2 Future investigations are planned to further investigate relationships between antenatal psychosocial stress and pregnancy outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Funding from:

1. 1 TL1 RR025016-01, UW Multidisciplinary Predoctoral Research Training Program (National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research)

2. 1 KL2 RR025015-01, NCRR, NIH Roadmap for Medical Research

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Antenatal psychosocial stress is common and high levels are significantly associated with maternal factors which are key contributors to adverse pregnancy outcomes.

References

- 1.Ruiz RJ, Fullerton JT. The measurement of stress in pregnancy. Nurs Health Sci. 1999;1:19–25. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2018.1999.00004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.ACOG Committee Opinion No. 343: psychosocial risk factors: perinatal screening and intervention. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:469–477. doi: 10.1097/00006250-200608000-00046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rondo PH, Ferreira RF, Nogueira F, Ribeiro MC, Lobert H, Artes R. Maternal psychological stress and distress as predictors of low birth weight, prematurity and intrauterine growth retardation. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2003;57:266–272. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Curry MA. The interrelationships between abuse, substance use, and psychosocial stress during pregnancy. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 1998;27:692–699. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.1998.tb02640.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heaman MI. Relationships between physical abuse during pregnancy and risk factors for preterm birth among women in Manitoba. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2005;34:721–731. doi: 10.1177/0884217505281906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dunn LL, Oths KS. Prenatal predictors of intimate partner abuse. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2004;33:54–63. doi: 10.1177/0884217503261080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martin SL, Griffin JM, Kupper LL, Petersen R, Beck-Warden M, Buescher PA. Stressful life events and physical abuse among pregnant women in North Carolina. Matern Child Health J. 2001;5:145–152. doi: 10.1023/a:1011339716244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bullock L, Bloom T, Davis J, Kilburn E, Curry MA. Abuse disclosure in privately and medicaid-funded pregnant women. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2006;51:361–369. doi: 10.1016/j.jmwh.2006.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jesse DE, Reed PG. Effects of spirituality and psychosocial well-being on health risk behaviors in Appalachian pregnant women. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2004;33:739–747. doi: 10.1177/0884217504270669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Orr ST, James SA, Miller CA, et al. Psychosocial stressors and low birthweight in an urban population. Am J Prev Med. 1996;12:459–466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jesse DE, Walcott-Mcquigg J, Mariella A, Swanson MS. Risks and protective factors associated with symptoms of depression in low-income African American and Caucasian women during pregnancy. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2005;50:405–410. doi: 10.1016/j.jmwh.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jesse DE, Swanson MS. Risks and resources associated with antepartum risk for depression among rural southern women. Nurs Res. 2007;56:378–386. doi: 10.1097/01.NNR.0000299856.98170.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zuckerman B, Amaro H, Bauchner H, Cabral H. Depressive symptoms during pregnancy: relationship to poor health behaviors. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989;160:1107–1111. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(89)90170-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Kroenke K, Hornyak R, Mcmurray J. Validity and utility of the PRIME-MD patient health questionnaire in assessment of 3000 obstetric-gynecologic patients: the PRIME-MD Patient Health Questionnaire Obstetrics-Gynecology Study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183:759–769. doi: 10.1067/mob.2000.106580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rodrigues T, Rocha L, Barros H. Physical abuse during pregnancy and preterm delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198(171):e1–e6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kelly RH, Russo J, Holt VL, et al. Psychiatric and substance use disorders as risk factors for low birth weight and preterm delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100:297–304. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alder J, Fink N, Bitzer J, Hosli I, Holzgreve W. Depression and anxiety during pregnancy: a risk factor for obstetric, fetal and neonatal outcome? A critical review of the literature. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2007;20:189–209. doi: 10.1080/14767050701209560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mcfarlane J, Parker B, Soeken K. Abuse during pregnancy: associations with maternal health and infant birth weight. Nurs Res. 1996;45:37–42. doi: 10.1097/00006199-199601000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bentley SM, Melville JL, Berry BD, Katon WJ. Implementing a clinical and research registry in obstetrics: overcoming the barriers. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2007;29:192–198. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2007.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Curry MA, Burton D, Fields J. The Prenatal Psychosocial Profile: a research and clinical tool. Res Nurs Health. 1998;21:211–219. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-240x(199806)21:3<211::aid-nur4>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Curry MA, Campbell RA, Christian M. Validity and reliability testing of the Prenatal Psychosocial Profile. Res Nurs Health. 1994;17:127–135. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770170208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders. Patient Health Questionnaire. JAMA. 1999;282:1737–1744. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Melvin CL, Tucker P. Measurement and definition for smoking cessation intervention research: the smoke-free families experience. Smoke-Free Families Common Evaluation Measures for Pregnancy and Smoking Cessation Projects Working Group. Tob Control. 2000;9 Suppl 3:III87–III90. doi: 10.1136/tc.9.suppl_3.iii87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sokol RJ, Martier SS, Ager JW. The T-ACE questions: practical prenatal detection of risk-drinking. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989;160:863–868. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(89)90302-5. discussion 868-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Midanik LT, Zahnd EG, Klein D. Alcohol and drug CAGE screeners for pregnant, low-income women: the California Perinatal Needs Assessment. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1998;22:121–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mcfarlane J, Parker B, Soeken K, Bullock L. Assessing for abuse during pregnancy. Severity and frequency of injuries and associated entry into prenatal care. JAMA. 1992;267:3176–3178. doi: 10.1001/jama.267.23.3176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Curry MA, Durham L, Bullock L, Bloom T, Davis J. Nurse case management for pregnant women experiencing or at risk for abuse. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2006;35:181–192. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2006.00027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Misra DP, O'campo P, Strobino D. Testing a sociomedical model for preterm delivery. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2001;15:110–122. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3016.2001.00333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Altarac M, Strobino D. Abuse during pregnancy and stress because of abuse during pregnancy and birthweight. J Am Med Womens Assoc. 2002;57:208–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martin SL, English KT, Clark KA, Cilenti D, Kupper LL. Violence and substance use among North Carolina pregnant women. Am J Public Health. 1996;86:991–998. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.7.991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lu MC, Chen B. Racial and ethnic disparities in preterm birth: the role of stressful life events. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:691–699. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Paul K, Boutain D, Agnew K, Thomas J, Hitti J. The relationship between racial identity, income, stress and C-reactive protein among parous women: implications for preterm birth disparity research. J Natl Med Assoc. 2008;100:540–546. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)31300-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Elizabeth Jesse D, Graham M, Swanson M. Psychosocial and spiritual factors associated with smoking and substance use during pregnancy in African American and White low-income women. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2006;35:68–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2006.00010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ludman EJ, Mcbride CM, Nelson JC, et al. Stress, depressive symptoms, and smoking cessation among pregnant women. Health Psychol. 2000;19:21–27. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.19.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weaver K, Campbell R, Mermelstein R, Wakschlag L. Pregnancy smoking in context: the influence of multiple levels of stress. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10:1065–1073. doi: 10.1080/14622200802087564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Williamson HA, Jr, Lefevre M, Hector M., Jr Association between life stress and serious perinatal complications. J Fam Pract. 1989;29:489–494. discussion 494-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hedegaard M, Henriksen TB, Sabroe S, Secher NJ. Psychological distress in pregnancy and preterm delivery. BMJ. 1993;307:234–239. doi: 10.1136/bmj.307.6898.234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Da Costa D, Larouche J, Dritsa M, Brender W. Variations in stress levels over the course of pregnancy: factors associated with elevated hassles, state anxiety and pregnancy-specific stress. J Psychosom Res. 1999;47:609–621. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(99)00064-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shand AW, Bell JC, Mcelduff A, Morris J, Roberts CL. Outcomes of pregnancies in women with pre-gestational diabetes mellitus and gestational diabetes mellitus; a population-based study in New South Wales, Australia, 1998–2002. Diabet Med. 2008;25:708–715. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2008.02431.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stella CL, O'brien JM, Forrester KJ, et al. The coexistence of gestational hypertension and diabetes: influence on pregnancy outcome. Am J Perinatol. 2008;25:325–329. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1078758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Copper RL, Goldenberg RL, Das A, et al. The preterm prediction study: maternal stress is associated with spontaneous preterm birth at less than thirty-five weeks' gestation. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:1286–1292. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(96)70042-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Neggers Y, Goldenberg R, Cliver S, Hauth J. The relationship between psychosocial profile, health practices, and pregnancy outcomes. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2006;85:277–285. doi: 10.1080/00016340600566121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pagel MD, Smilkstein G, Regen H, Montano D. Psychosocial influences on new born outcomes: a controlled prospective study. Soc Sci Med. 1990;30:597–604. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(90)90158-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wadhwa PD, Sandman CA, Porto M, Dunkel-Schetter C, Garite TJ. The association between prenatal stress and infant birth weight and gestational age at birth: a prospective investigation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;169:858–865. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(93)90016-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dole N, Savitz DA, Siega-Riz AM, Hertz-Picciotto I, Mcmahon MJ, Buekens P. Psychosocial factors and preterm birth among African American and White women in central North Carolina. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:1358–1365. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.8.1358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rini CK, Dunkel-Schetter C, Wadhwa PD, Sandman CA. Psychological adaptation and birth outcomes: the role of personal resources, stress, and sociocultural context in pregnancy. Health Psychol. 1999;18:333–345. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.18.4.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hobel C, Culhane J. Role of psychosocial and nutritional stress on poor pregnancy outcome. J Nutr. 2003;133:1709S–1717S. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.5.1709S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gennaro S, Hennessy MD. Psychological and physiological stress: impact on preterm birth. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2003;32:668–675. doi: 10.1177/0884217503257484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Paarlberg KM, Vingerhoets AJ, Passchier J, Dekker GA, Van Geijn HP. Psychosocial factors and pregnancy outcome: a review with emphasis on methodological issues. J Psychosom Res. 1995;39:563–595. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(95)00018-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hobel CJ, Goldstein A, Barrett ES. Psychosocial stress and pregnancy outcome. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2008;51:333–348. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0b013e31816f2709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lu MC, Kotelchuck M, Culhane JF, Hobel CJ, Klerman LV, Thorp JM., Jr Preconception care between pregnancies: the content of internatal care. Matern Child Health J. 2006;10:S107–S122. doi: 10.1007/s10995-006-0118-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]