Abstract

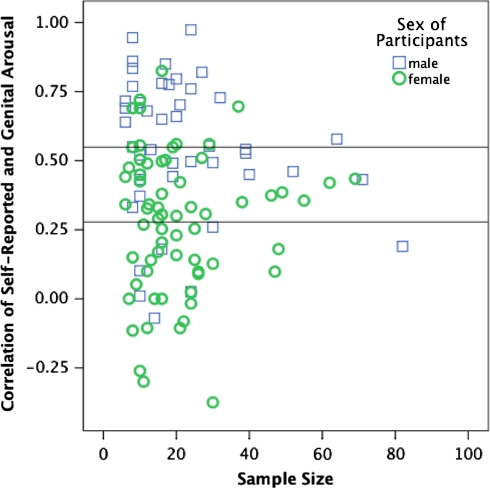

The assessment of sexual arousal in men and women informs theoretical studies of human sexuality and provides a method to assess and evaluate the treatment of sexual dysfunctions and paraphilias. Understanding measures of arousal is, therefore, paramount to further theoretical and practical advances in the study of human sexuality. In this meta-analysis, we review research to quantify the extent of agreement between self-reported and genital measures of sexual arousal, to determine if there is a gender difference in this agreement, and to identify theoretical and methodological moderators of subjective-genital agreement. We identified 132 peer- or academically-reviewed laboratory studies published between 1969 and 2007 reporting a correlation between self-reported and genital measures of sexual arousal, with total sample sizes of 2,505 women and 1,918 men. There was a statistically significant gender difference in the agreement between self-reported and genital measures, with men (r = .66) showing a greater degree of agreement than women (r = .26). Two methodological moderators of the gender difference in subjective-genital agreement were identified: stimulus variability and timing of the assessment of self-reported sexual arousal. The results have implications for assessment of sexual arousal, the nature of gender differences in sexual arousal, and models of sexual response.

Keywords: Sexual psychophysiology, Sexual arousal, Sex difference, Gender difference, Plethysmography, Photoplethysmography

Introduction

The human sexual response is a dynamic combination of cognitive, emotional, and physiological processes. The degree to which one product of these processes, the individual’s experience of sexual arousal, corresponds with physiological activity is a matter of interest to many researchers and practitioners in sexology because subjective experience (or self-report) and genital measures of sexual arousal do not always agree. In this article, we label this correspondence concordance or subjective-genital agreement.

Examples of low subjective-genital agreement abound in both clinical and academic sexology. Some men report feeling sexual arousal without concomitant genital changes (Rieger, Chivers, & Bailey, 2005) and experimental manipulations can increase penile erection without affecting subjective reports of sexual arousal (Bach, Brown, & Barlow, 1999; Janssen & Everaerd, 1993). Similarly, some women show genital responses without reporting any experience of sexual arousal (Chivers & Bailey, 2005) and self-reported sexual arousal is subject to impression management, as in the greater reluctance among women high in sex guilt to report feeling sexually aroused (Morokoff, 1985).

Thus, determining the extent of the agreement between self-reported and genital measures of sexual arousal has both practical and theoretical significance. Practically, the majority of researchers and clinicians who assess sexual arousal do not have access to measures of genital response and, therefore, often rely on self-report. Those who employ self-report measures would like to know the extent to which they are measuring the same response as clinicians or researchers who use genital measures and vice versa. Moreover, knowing the extent of the agreement between self-reported and genital measures of sexual arousal, and identifying moderators of this subjective-genital agreement, would inform our models of sexual response, our understanding of sexual dysfunctions, and psychometric methods to assess each aspect of sexual response.

One of the most frequently suggested moderators of subjective-genital agreement is gender; studies of men tend to produce higher correlations between measures of subjective and genital sexual arousal than studies of women (for a narrative review, see Laan & Janssen, 2007). Two positions can be described regarding gender as a moderator of subjective-genital agreement. One position is that female and male sexual response systems are truly similar, but the lower concordance estimates observed among women are the result of methodological issues in these studies, such as differences in the assessment devices or procedures that are used. The other position accepts the gender difference in concordance as real, whether it is a result of fundamental differences in sexual response or the effects of learning and other environmental influences. Before we can determine which of these positions has merit, however, the size and direction of the gender difference in concordance must be clearly documented.

The Present Study

The purpose of this meta-analysis was to provide a quantitative review of the sexual psychophysiology research examining self-reported and genital sexual arousal in women and men. The primary goal was to determine if a gender difference in the concordance between psychological and physiological measures of sexual response was observed across these studies. We also examined potential moderators of concordance to determine the extent to which the observed gender difference in concordance might represent a real gender difference or methodological artifact, and to test theoretically-derived hypotheses drawn from sexual selection, information processing, and learning theories regarding factors that influence human sexual response. We focused on these particular theories as compelling ultimate or proximate explanations of gender differences in sexual response, respectively, and because we could test hypotheses drawn from these theories using the variables that could be coded in this meta-analysis. Potential moderators are discussed in the next section.

The Gender Difference in Concordance is Due to Methodological Artifact

It may be that there is no real gender difference in concordance, but the current methods of assessing self-reported and genital sexual responses attenuate concordance estimates in women or increase concordance estimates in men. The gender difference in concordance, therefore, might be the result of methodological factors. These could occur at any stage of a laboratory paradigm designed to evoke sexual arousal, have participants assess their sexual response, objectively measure their sexual response, and calculate an index of subjective-genital agreement. These stages involve variation in stimulus characteristics (modality, content, length, and variation in sexual stimuli); assessment of self-reported sexual arousal (method of reporting, timing, operationalization); assessment of genital sexual arousal; statistical methods (type of correlation, number of data points); and participant characteristics (age for both men and women and hormonal fluctuations for women). Below, we consider each set of moderators and the influence they may have on concordance estimates.

Stimulus Characteristics

Stimulus Modality

Sexual arousal is typically elicited in laboratory settings by exposure to internal (fantasy) or external (visual images or audiotaped descriptions of sexual acts) sources of sexual stimuli. Modality effects have been observed, such that women show greater subjective and genital responses to audiovisual depictions of sexual activity compared with audiotaped descriptions of sexual interactions or sexual fantasy (Heiman, 1980; Stock & Geer, 1982). Men also demonstrate greater subjective and genital responses to audiovisual depictions of sexual interactions compared with audiotaped descriptions of sexual activity or still pictures of couples engaged in intercourse (Sakheim, Barlow, Beck, & Abrahamson, 1985). Audiovisual depictions of couples engaged in intercourse yield greater genital responses in both women and men than do still photographs of nude women and men (Laan & Everaerd, 1995a, 1995b; Laan, Everaerd, van Aanhold, & Rebel, 1993; Mavissakalian, Blanchard, Abel, & Barlow, 1975). It is unclear, however, which modality of sexual stimulus, if any, produces greater concordance of subjective and genital responses in either women or men.

There is evidence of a gender difference in responses to specific sexual content. Still photographs of nude or partially clothed women or men do not generate either self-reported or genital sexual arousal in heterosexual women (Laan & Everaerd, 1995a, 1995b), but are sufficient to generate substantial subjective and genital responses in heterosexual men (Tollison, Adams, & Tollison, 1979). For men, depictions of affectionate, nonexplicit interactions (e.g., cuddling, kissing) between clothed women and men significantly increase subjective and genital responses but, for women, both significant arousal responses and null effects to these same stimuli have been reported (Suschinsky, Lalumière, & Chivers, 2009; Wincze, Venditti, Barlow, & Mavissakalian, 1980). More recently, we have found that both heterosexual and homosexual men, and homosexual women but not heterosexual women, showed genital responses to film depictions of their preferred sex engaged in nude, nonsexual activities, such as walking on the beach (Chivers, Seto, & Blanchard, 2007).

The inclusion of sexual vocalizations (such as sighs, moans, and grunts) in audiovisual sexual stimuli augments both subjective and genital responses among men (Gaither & Plaud, 1997), but not among women (Lake Polan et al., 2003). Other data suggest that including vocalizations amplifies self-reported sexual arousal in both women and men (Pfaus, Toledano, Mihai, Young, & Ryder, 2006). For other kinds of content, however, both women and men respond similarly: audiovisual depictions of couples engaging in sexual intercourse elicited greater subjective and genital responses than did films of solitary women or men masturbating in both sexes (Chivers et al., 2007).

According to sexual selection theory, the importance of visual sexual cues to sexual responses may differ between women and men, influencing their appraisal of their sexual arousal. Symons (1979) discussed gender differences in processing of visual and nonvisual forms of erotica and suggested that visual cues are more salient for men. A study examining brain activation during sexual arousal in women and men supports Symons’ notion that visual sexual stimuli possess greater reward value for men, as evidenced by differential activation of reward-related pathways (Hamann, Herman, Nolan, & Wallen, 2003). This study did not compare activation patterns between visual and other modalities of sexual stimuli, however, so it is not clear whether differential activation pertained to sexual stimuli in general or to only particular modalities of sexual stimuli.

For men, we expected concordance to be higher for visual (photographs, videos) than for nonvisual (fantasy, text, auditory descriptions) modalities. For women, we speculated, based on observations of the greater female consumption of nonvisual forms of erotic literature (for reviews, see Malamuth, 1996; Salmon & Symons, 2003), that concordance would be greater when assessed using nonvisual modalities of sexual stimuli.

We also hypothesized that, for women, self-generated sexual stimuli (sexual fantasies) would result in significantly greater concordance than stimuli produced by others, even though fantasy is likely to produce lower levels of genital response (Heiman, 1980). The rationale for this hypothesis is that self-generated stimuli are less likely to evoke negative affect because women would be unlikely to imagine content that they find unpleasant. Negative affect appears to reduce self-reported sexual arousal and thus could reduce concordance (Laan & Janssen, 2007). Consistent with this idea, one study reported that subjective-genital agreement was greater among women with sexual arousal disorder when sexual fantasy was used as a sexual stimulus; concordance was positive with sexual fantasy, negative while listening to audiotaped stories, and not significantly different from zero during a film presentation (Morokoff & Heiman, 1980). Another study showed greater concordance estimates during sexual fantasy compared to audiotaped stories during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle (Schreiner-Engel, Schiavi, & Smith, 1981).

Stimulus Length

We predicted that stimulus length would be positively associated with concordance, to the extent that longer stimuli could produce greater variation in subjective and genital responses and thus would allow for larger correlations than shorter stimuli that produced less variation. Response variation delimits the size of the correlation that can be obtained: Thus, an absence of both subjective and genital sexual arousal during a stimulus presentation would indicate high concordance, yet would produce a correlation of zero; the same situation applies if a person produces maximal subjective and genital responses throughout a stimulus presentation. Stimulus length may also be associated with concordance because longer stimuli could produce more reliable estimates of response than shorter stimuli.

Stimulus Variation

Increasing the potential variability in self-reported and genital sexual responses can also be achieved by using a range of sexual stimuli that vary in specific content and modality; variation in both self-reported and genital sexual arousal across different modalities of sexual stimuli has been observed for both women and men (Heiman, 1980; Sakheim et al., 1985). We would also expect higher subjective-genital agreement for studies that presented both preferred and nonpreferred stimuli, because showing only preferred or only nonpreferred stimuli1 may result in a restriction of range in response, thereby restricting the potential magnitude of a subjective-genital correlation.

Measurement of Self-Reported Sexual Arousal

Method of Reporting

Self-reported sexual arousal (subjective response) is the individual’s appraisal and report of their emotional state of sexual arousal. Most researchers ask participants to rate their sexual arousal either after the presentation of a sexual stimulus, using Likert-type items, or during the presentation of a sexual stimulus, using an apparatus such as a lever that the participant can move as they subjectively respond to the stimulus. Laan (1994) reported good internal consistency (α = .82) for a measure of women’s self-reported sexual arousal that included the following items: overall sexual arousal, strongest sexual arousal, and genital sensations, all rated using unipolar visual analog scales. No research on other measures of subjective response reliability, such as test–retest reliability, has been reported in the literature.

Operationalization

It is important to note that a subjective sexual response is defined differently here from a self-reported genital response; the former refers to appraisal of an emotional state of sexual arousal whereas the latter is a subjective estimate of the extent of one’s physiological responding, such as estimating the percentage of erection attained for men or the perception of genital sensations or wetness for women. It is not clear how much of one’s appraisal of subjective sexual arousal is influenced by one’s perception of genital responding, or vice versa, but these measures are highly positively correlated in both women (Slob, Bax, Hop, Rowland, & van der Werff ten Bosch, 1996) and men (Rowland & Heiman, 1991). Examining the correlations between these two self-report measures and physiologically-measured genital sexual arousal may inform understanding of how experiencing sexual arousal and perceiving physical changes are related to genital response.

Timing of Assessment

Subjective sexual arousal can be assessed at different times during sexual psychophysiology data acquisition. Logically and statistically, the potential correlation between subjective and genital sexual arousal should be highest when they are measured contiguously. Conversely, the correlation should be lower when subjective response is recorded after a trial has ended, or after a study session has ended, because the participant’s report of their subjective sexual arousal may be influenced by recall or other kinds of cognitive biases. Even if it is not correct that contiguous assessment produces the highest correlation between subjective and genital arousal, researchers and clinicians are probably most interested in concordance for arousal responses that occur simultaneously and less interested in the agreement between genital response at a particular point in time with subjective response after some time has elapsed (e.g., genital responses during a short period of sexual stimulation and subjective responses minutes later, after the sexual stimulation has stopped).There is evidence that using a lever, or similar device, contiguous with processing of a sexual stimulus does not affect genital responding in women, but does result in lower genital responses in men (Wincze et al., 1980), perhaps as a result of distraction (Geer & Fuhr, 1976). Some researchers have reported that assessing subjective sexual arousal contiguously results in lower concordance than using post-trial ratings in women (Laan et al., 1993). Thus, we predicted that the timing of the assessment of subjective sexual arousal would moderate concordance and that gender differences in the effects of assessment timing on sexual response might help explain the gender difference in concordance that has been observed.

Measurement of Genital Sexual Arousal2

Phallometry

Various physiological parameters, such as pupil dilation, heart rate, and galvanic skin response, have been examined as potential objective measures of sexual arousal, but changes in penile erection, assessed using penile plethysmography, are the most specific measure of sexual response in men (Zuckerman, 1971). An objective method of measuring penile erection was developed by Freund (1963). Changes in penile circumference, measured using a gauge placed around the shaft of the penis, or changes in penile volume (assessed using gas displacement in a sealed cylinder placed over the penis) are the most commonly used methods in sexual arousal research. Increases in penile circumference or volume are interpreted as evidence of greater genital sexual arousal. Circumferential and volumetric measurements are highly correlated when men show at least 2.5 mm of penile circumference change in the laboratory (Kuban, Barbaree, & Blanchard, 1999).

Regarding discriminative validity, penile responses can distinguish heterosexual and homosexual men, men who are sexually attracted to prepubescent children from those who are sexually attracted to adults, fetishists from nonfetishists, rapists from nonrapists, and sadistic men from nonsadistic men (e.g., Blanchard, Klassen, Dickey, Kuban & Blak, 2001; Freund, 1963; Freund, Seto, & Kuban, 1996; Lalumière, Quinsey, Harris, Rice, & Trautrimas, 2003; Sakheim et al., 1985; Seto & Kuban, 1996). Penile responses can also distinguish sexually functional men from men with sexual dysfunctions, such as men with premature ejaculation (Rowland, van Diest, Incrocci, & Slob, 2005).

Regarding predictive validity, phallometrically-assessed sexual arousal to stimuli depicting children or sexual violence is an important predictor of sexual reoffending among sex offenders (Hanson & Morton-Bourgon, 2005). Although the predictive validity of phallometrically-assessed sexual arousal in nonforensic samples has not been systematically examined, one study found that penile responses to sexual stimuli in the laboratory were related to increases in sexual behavior on the day following the laboratory session (Both, Spiering, Everaerd, & Laan, 2004).

Vaginometry

Objective assessment of the female genital response began in the 1970s with the development of the vaginal photoplethysmograph (Sintchak & Geer, 1975; for a more thorough discussion, see Geer & Janssen, 2000). The photoplethysmograph—a small, acrylic probe the size of a menstrual tampon—records haemodynamic changes in the vaginal epithelium using light reflectance. The photoplethysmograph signal is filtered into two components: vaginal blood volume (VBV), which reflects slow changes in blood pooling, and vaginal pulse amplitude (VPA), which reflects phasic changes in vasocongestion with each heart beat. These two vaginal signals have different properties (Hatch, 1979). Changes in VPA are specific to sexual stimuli, while VBV appears to increase in response to both sexual and anxiety-inducing stimuli (Laan, Everaerd, & Evers, 1995; Suschinsky et al., 2009). VPA typically returns faster to a pretrial baseline response than VBV (Laan, Everaerd, & Evers, 1995). No consistent evidence for menstrual cycle effects on VPA has been observed (Hoon, Bruce, & Kinchloe, 1982; Meuwissen & Over, 1992; Schreiner-Engel et al., 1981). Because the VPA signal demonstrates better psychometric properties than VBV, the majority of researchers have reported VPA.

Vaginometry using VPA demonstrates good reliability (Prause, Janssen, Cohen, & Finn, 2002; Wilson & Lawson, 1978) and there is evidence of its predictive and discriminative validity. Vaginal responses to sexual stimuli are related to increases in post-laboratory sexual behavior (Both et al., 2004). VPA assessed during baseline response can distinguish premenopausal women from postmenopausal women (Brotto & Gorzalka, 2002; Laan, van Driel, & van Lunsen, 2008; Laan, van Lunsen, & Everaerd, 2001), and VPA assessed during sexual response can differentiate heterosexual from homosexual women when stimuli depicting solitary males and females are used (Chivers et al., 2007). It is unclear whether VPA can discriminate sexually dysfunctional from functional women. The majority of studies find no differences in genital response between sexually functional and dysfunctional groups (for additional data and a review, see Laan et al., 2008). One study, however, did find VPA differences between subgroups of women with and without female sexual arousal disorder, using the newer sexual dysfunction definitions (Basson et al., 2003) discriminating between women reporting absent or impaired genital sexual arousal (genital sexual arousal disorder), women reporting absence of or markedly diminished feelings of sexual arousal (subjective sexual arousal disorder), and women reporting absence of, or markedly diminished feelings of sexual arousal, sexual excitement, or sexual pleasure (combined genital and subjective sexual arousal disorder) (Brotto, Basson, & Gorzalka, 2004). This discrepancy in the discriminative validity of VPA reflects recent changes in DSM-IV criteria for female sexual arousal disorder (FSAD); FSAD groups from previous studies are best compared to the combined genital and subjective sexual arousal disorder group used by Brotto et al., and these women did not differ from the control group in terms of genital responsiveness. Poor discrimination in genital response on the basis of sexual functioning, however, likely reflects uncertainty regarding the role of genital response in FSAD rather than psychometric limitations of VPA.

The type of signal obtained from vaginal photoplethysmography may affect concordance. Because VPA and VBV reflect different, though related, vasocongestive processes (Geer & Janssen, 2000), it is possible they are differentially related to subjective sexual arousal. For example, VBV has been shown in one study to be more reactive to negative affect (Laan, Everaerd, & Evers, 1995). VBV may, therefore, correlate better with self-reports of sexual arousal than VPA, to the extent that self-reported sexual arousal is influenced by emotional state.

No consensus exists on how VPA data should be transformed prior to statistical analysis (Hatch, 1979). Because the unit of change (mV) does not correspond to a clearly meaningful physiological correlate3 (Levin, 1992), comparisons between women using raw mV change scores are difficult to interpret. Some authors report change in VPA as a percent increase over baseline (Both et al., 2004; Heiman, 1977), sometimes called the “maximum change technique” (Rellini & Meston, 2006). Another means of transforming VPA is to ipsatize genital response data within participants (Chivers, Rieger, Latty, & Bailey, 2004). Responses are, therefore, expressed as a function of the individual’s own distribution of responses across a set of sexual stimuli, in SD units, making relative comparisons of responses to different stimuli across participants meaningful. Another method is to log-transform genital VPA, because raw scores typically demonstrate positive skew (Meston, 2006). It is unknown which method of data reduction for VPA data is the best in terms of maximizing the discriminative or predictive validity of vaginal photoplethysmography.

Thermography

The second most commonly used physiological measure of female genital response is thermography, most commonly assessed using a labial thermistor. This device consists of a thermistor placed on a small clip that is attached to the labia minora. It measures changes in skin temperature of the labia minora during genital vasocongestion. The labial thermistor has also shown good psychometric properties. Labial temperature reliably increases with exposure to sexual, but not neutral, stimuli (Henson, Rubin, Henson, & Williams, 1977). For the majority of women, VPA, VBV, and labial temperature are positively correlated with each other during sexual stimuli, but agreement between these genital measures is variable during presentations of nonerotic stimuli (Henson, Rubin, & Henson, 1979).

Payne and Binik (2006) have argued that labial temperature is a more consistent measure of genital response than VBV or VPA and is more strongly correlated with self-reported sexual arousal than VPA. Labial temperature is unaffected by orgasm, unlike VPA (Henson, Rubin, & Henson, 1982). At the same time, menstrual cycle effects have been reported for labial temperature change recorded during the follicular and luteal phases of the menstrual cycle (Slob, Ernste, & van der Werff ten Bosch, 1991; Slob et al., 1996). Onset of change in labial temperature is typically slower than VPA and temperature takes longer to return to a pretrial level of response; some studies reported that labial temperature was more consistent between testing sessions than VPA or VBV (Payne & Binik, 2006, but see also Slob, Koster, Radder, & van der Werff ten Bosch, 1990; Slob et al., 1991, 1996). Unlike VPA, the units of change are in Celsius degrees, and thus the unit of response can be directly compared across participants. On the other hand, unlike VPA, thermistor readings may be subject to a ceiling effect wherein genital responding continues to increase but labial temperature reaches a physiological maximum.

The type of genital measure used to assess sexual response in women may affect concordance estimates. Vaginal photoplethysmography measures changes in vaginal vasocongestion, which is not directly perceptible in women, whereas thermography measures change in the temperature of the external genitalia, which may be more perceptible. There is some preliminary evidence suggesting that awareness of changes in body temperature is related to feelings of sexual arousal; using factor analysis, Laan (1994) reported that awareness of labial temperature change loaded onto both a sexual feelings and a physical feelings factor, suggesting some overlap between temperature changes during both sexual and general physiological arousal. Thus, thermography may produce higher agreement with self-reported sexual arousal than vaginal photoplethysmography, to the extent that subjective response is influenced by an awareness of genital sensations. In addition, VPA may assess initial changes in blood flow before any labial temperature change occurs, and this may also affect concordance estimates because VPA would capture a fuller range of genital response.

Comparisons Between Female and Male Sexual Response

Though they measure the same genital process of vasocongestion, vaginal photoplethysmography and penile plethysmography use different physiological endpoints to estimate sexual response; vaginal photoplethysmography uses light reflectance to assess color change in the vaginal epithelium, whereas penile plethysmography assesses changes in the size of the penis. If an identical physiological endpoint, such as temperature change using thermography, was used for both women and men, would the gender difference in concordance still be found? For both women and men, awareness of temperature changes in the genitals may be an important cue of sexual arousal. Alternatively, information processing theory as applied to sexual functioning (see below) would posit that, regardless of physiological endpoints, a woman’s experience of sexual arousal is not highly influenced by her perception of physiological changes. It is unclear whether type of genital assessment method moderates a gender difference in concordance.

Statistical Methods

Type of Correlations

There are at least two ways of thinking about the concordance of self-reported and genital sexual arousal (Geer & Janssen, 2000). The first way has to do with the extent to which self-reported and genital responses agree within an individual; in other words, do individual changes in self-reported sexual arousal correspond with a similar change in genital sexual arousal, across different stimuli and different conditions? This type of concordance can be estimated by calculating within-subjects correlations between measures of self-reported and genital sexual arousal. Each participant produces a set of data points that is used to calculate a within-subjects correlation for that participant, which can then be averaged across the participants in a group (Bland & Altman, 1995a).

The second way to think about concordance has do to with the extent to which self-reported and genital responses agree within a group; in other words, are the individuals who produce the largest self-reported responses also the same individuals who produce the largest genital responses? This type of concordance can be estimated by calculating between-subjects correlations between measures of self-reported and genital sexual arousal. Each participant produces a pair of data points and the set of data points for the participants in a group are used to calculate a between-subjects correlation (Bland & Altman, 1995b).

It is possible that the gender difference in subjective-genital agreement depends on how concordance is conceptualized and thus how the correlation is calculated. In addition, researchers may be more interested in intra-individual or intra-group concordance, depending on the questions they are examining. We therefore examined the impact of type of correlation calculation in this meta-analysis.

Number of Data Points

Statistically, more reliable measurements tend to be obtained with a higher number of observations, so studies using larger samples (between-subjects correlations), a greater number of stimulus trials (within-subjects correlations), or a greater number of measurement epochs (within-subject correlations) increase the number of data points used to calculate concordance, and should therefore yield more reliable estimates of concordance. As concordance can be calculated two ways—within-subjects correlations representing the number of measurements of concordance taken for each participant or between-subjects correlations representing the number of subjects in the study—we examined number of data points separately for each type of correlation.

Participant Characteristics

Monthly fluctuations in reproductively-related hormones may be related to subjective-genital agreement among women. There is some evidence that estrogens are related to sexual response (Heiman, Rowland, Hatch, & Gladue, 1991) and that androgens can influence female subjective and genital sexual arousal (Tuiten, van Honk, Bernaards, Thijssen, & Verbaten, 2000, reported positive effects; however, Apperloo et al., 2006, reported null effects) and genital responsiveness (Slob et al., 1991). Because menstrual-cycle effects have been demonstrated for other processes related to sexual interest (e.g., Gangestad & Cousins, 2001; Gangestad, Garver-Apgar, Simpson, & Cousins, 2007), and women report their greatest interest in sex at mid-cycle (van Goozen, Wiegant, Endert, & Helmond, 1997), it is plausible that concordance may vary across the menstrual cycle because of the effects of hormone fluctuations on both subjective and genital responses (Schreiner-Engel et al., 1981). Few studies, however, have controlled for cycle variability among female participants. An indirect means of assessing the impact of cycle variation on concordance is to compare estimates from women who are not naturally cycling, such as women using oral contraceptives, with women who are naturally cycling.

The Gender Difference is Due to Differences in Learning and Attention

We may find that methodological moderators do not adequately explain the gender difference in agreement between subjective and genital sexual responses. If this is the case, then we need to consider other factors to explain the gender difference in concordance.

A learning approach explains the gender difference in subjective-genital agreement as a result of differential experiences, the sources of which are at least threefold. First, men have an obvious external cue of their genital response by having a penis that they can see when unclothed and feel when it presses against the body or against clothing during erection. Women’s genital responses, however, are hidden from view and produce less prominent somatosensory cues. A related point is that women’s less obvious genital response may hamper women’s familiarity with their genital anatomy (Gartrell & Mosbacher, 1984). Second, a plethora of negative cultural messages regarding female genitalia and menstruation may pair feelings of shame or embarrassment with genital sensations for women (Steiner-Adair, 1990). Third, women masturbate less often than men (Oliver & Hyde, 1993); masturbation may be one of the best activities for learning about one’s genitals and sexual responding, and pairing positive feelings with sexual activities. For example, prior research has shown that women who masturbate more frequently tend to report higher subjective sexual arousal (Laan & Everaerd, 1995a, 1995b) and show greater concordance (Laan et al., 1993).

Following a similar logic, older participants would be expected to produce greater subjective-genital agreement, especially older female participants, because they have more experience with attending to their genital sensations across different sexual experiences. Consistent with this hypothesis, Brotto and Gorzalka (2002) found that age was positively correlated with subjective-genital agreement among older pre-menopausal women. However, the effect of age may not be linear because there may also be a cohort effect on familiarity and comfort with one’s genitals and with masturbation, such that much older women would show lower rather than higher concordance. If this particular hypothesis is correct, then we would expect a curvilinear relationship between age and concordance among women. Indeed, Brotto and Gorzalka reported that concordance estimates from older post-menopausal women (Mage, 56 years) were lower than those of older pre-menopausal women (Mage, 48 years).

If cultural and anatomical differences have reduced women’s awareness of their genitals, directing their attention back to their genitals should improve concordance; similar effects should be observed for men. For women, however, the data do not support this idea. Merrit, Graham, and Janssen (2001) found that correlations between sexual feelings and genital sexual arousal remained low even when women were asked to estimate their genital responses during erotic stimulation. Similarly, Cerny (1978) found that, even when women received feedback about their level of vaginal engorgement, correlations were low and statistically nonsignificant. Conscious efforts of women to monitor their genital responses may thus not enhance concordance. If learning or attention do not explain the gender difference in concordance, then perhaps differences in information processing may contribute.

The Gender Difference is Due to Differences in Conscious and Unconscious Processing of Sexual Stimuli and Regulation of Genital Arousal

Another way in which the gender difference in concordance could manifest is through differential processing of sexual stimuli. This extension of information processing theory to sexual response predicts that gender differences in concordance emerge because of gender differences in the relative contribution of conscious (cognitively appraised or controlled, explicit) and unconscious (automatic, implicit) processes associated with sexual response (Spiering, Everaerd, & Laan, 2004): Because of men’s more prominent genital anatomy, automatic processes play a greater role in their experience of sexual arousal, resulting in greater concordance; for women, the meanings generated by sexual stimuli may have a greater influence on their subjective appraisal. In support of this notion, Laan (1994) showed that women’s positive appraisal of sexual stimuli was positively correlated with subjective sexual arousal. Additionally, women may report greater negative affect when presented with sexual stimuli, may not appraise some sexual stimuli as “sexual,” or may edit their self-report of feeling sexually aroused because of socially desirable responding (Laan & Janssen, 2007; Morokoff, 1985).

Cognitive models of sexual response and dysfunction propose that positive affect directs attention to erotic stimuli, thereby increasing sexual response, whereas negative affect interferes in the processing of sexual cues, resulting in lower sexual response (see Barlow, 1986). Lower concordance among women may reflect their experience of negative affect while watching the conventional, commercially available erotica that is primarily produced for men and typically used in psychophysiological studies. If information processing theory is correct, then using stimuli that produce less negative affect and more positive sexual appraisals may influence women’s subjective-genital agreement. For example, women reported greater sexual arousal to films that were female-centered, instead of typical commercially available sexual films, but did not show greater genital response to female-centered films (Laan, Everaerd, van Bellen, & Hanewald, 1994). Moreover, Laan et al. (1994) demonstrated that women reported greater negative affect to typical commercial erotica and greater positive affect to female-produced erotica.

Female-centered sexual films are characterized by depictions of women as sexual initiators, a focus on a woman’s pleasure, and sexual interactions that are often presented in the context of an intimate relationship between the actors. In contrast, typical commercially-available sexual films tend to focus instead on men as the sexual initiators, the man’s pleasure, and anonymous or casual sexual interactions. Studies that use commercial erotica would therefore be expected to decrease subjective sexual arousal (but not genital response) for women, and so we predict that presenting female-centered erotica would increase subjective-genital agreement among women.

More sexually explicit stimuli elicit greater negative affect among women than among men (Laan & Everaerd, 1995a, 1995b) and women typically have less exposure to sexually explicit materials than men (Hald, 2006). According to information processing theory, sexually explicit stimuli may impede the subjective experience of sexual arousal in women because these films elicit negative affect, and negative affect competes or interferes with the positive affect that usually underlies sexual arousal. Alternatively, more sexually explicit stimuli may, in fact, increase concordance among women, compared with less explicit or erotic stimuli because sexually explicit stimuli evoke greater increases in genital vasocongestion (Heiman, 1980) and, based on signal detection theory, one would expect that detection of a physiological event is dependent upon greater change in that physiological process (Laan, Everaerd, van der Velde, & Geer, 1995).

Asking participants to sexually fantasize might be expected to decrease negative affect, because most participants would be expected to imagine sexual content that they consider to be sexual and enjoyable and, therefore, would experience less negative and more positive affect. This is expected to be true even if some participants have difficulty in fantasizing in the laboratory. Using fantasy should increase women’s subjective-genital agreement to a greater extent than for men if this supposition is correct. In contrast, exposure to conventional sexually explicit materials targeted at a male audience where relatively little attention is paid to contextual factors would be expected to decrease subjective sexual arousal and thereby decrease subjective-genital agreement among women.

If negative affect interferes with positive appraisal of sexual stimuli among women, then experimental instructions would also be expected to have an impact on subjective-genital agreement. Conditions involving instructions to focus on one’s genital sensations should reduce attention to the negative aspects of the sexual stimulus, increase attention to physiological sensations, and thereby increase subjective-genital agreement in women and reducing the observed gender difference. Alternatively, attending to one’s genital sensations may increase the participant’s self-consciousness and interfere with concordance.

Finally, simultaneous assessment of subjective sexual arousal should result in higher subjective-genital agreement compared to post-trial assessment, because there is much less time for conscious processing of sexual stimuli, such as cognitive interference from negative affect, to take place in the moments after the trial has ended. This hypothesis does not require conscious processing of the sexual content, as interference could involve unconscious (automatic) processes. Because cognitive interference due to negative affect is expected to be greater for women, we predicted that the impact of simultaneous assessment on concordance should be larger for women than for men.

An off-shoot of information processing theory is that sexually dysfunctional participants, whether male or female, are expected to produce lower subjective-genital agreement than sexually functional participants. Models of sexual dysfunction propose that sexually dysfunctional individuals differ by having more negative cognitions and more negative affect in response to sexual stimuli. Lower concordance among sexually dysfunctional persons may reflect an absence of sexual feelings while experiencing genital responses, as has been demonstrated among women with sexual arousal disorder (Laan et al., 2008), or feeling sexually aroused but not experiencing the expected changes in genital vasocongestion, as in men who have erectile difficulties (Barlow, 1986). The potential for concordance to vary with sexual functioning has been demonstrated in studies of sexually dysfunctional women; women with sexual arousal problems report lower subjective sexual arousal to sexual stimuli in the laboratory, but do not show significantly lower genital responses when compared to women without sexual arousal problems (e.g., Laan et al., 2008; Morokoff & Heiman, 1980).

Summary of Study Hypotheses

We propose the following hypotheses regarding potential moderators, distinguishing between those that test methodological explanations for variation in subjective-genital agreement and those that test theoretically-derived explanations for low concordance in women. We first hypothesize that a reliable, overall gender difference in concordance will be observed, followed by 10 hypotheses based on methodological considerations and 5 predictions based on theoretical considerations.

There will be an overall gender difference in subjective-genital agreement, with men producing higher concordance estimates than women;

Men will show greater concordance for visual sexual stimuli and women will show greater concordance for nonvisual sexual stimuli;

Including a variety of different stimulus categories or modalities of sexual stimuli will yield higher subjective-genital correlations in both genders;

Higher subjective-genital agreement is expected from studies with more stimulus trials in both genders;

Longer stimuli will produce greater subjective-genital correlations in both genders;

Higher subjective-genital agreement is expected in women when subjective responses are recorded contiguously with the recording of genital responses, compared to post-trial assessments;

Higher subjective-genital agreement is expected for subjective response that is defined as perception of genital changes versus feeling sexually aroused in both genders;

Thermography will yield higher estimates of concordance than vaginal photoplethysmography in women;

VBV measurement of genital vasocongestion will show greater concordance than VPA in women;

Concordance calculated using within-subjects correlations will be higher than those calculated between-subjects in both genders;

Concordance will improve with the number of data points used to calculate the correlation in both genders;

Subjective-genital agreement will be more strongly and positively correlated with age among women than among men;

Samples of women receiving sex hormones through oral contraceptives will produce lower correlations than samples of women who are naturally cycling;

Women are expected to show greater subjective-genital agreement when presented with female-centered stimuli, while men will show no difference or might even show less subjective-genital agreement, in comparison to typical commercial sexual content;

Women will show higher concordance for erotic versus sexually explicit films. Men will show the opposite pattern;

Non-clinical samples of sexually functional participants will produce higher estimates of subjective-genital agreement than clinical samples of sexually dysfunctional participants in both genders.

Method

Studies were identified by searching major computerized reference databases (PsycInfo, Medline, PubMed) and by examining the reference lists of relevant studies. The following were the search terms employed, with asterisks indicating variations (e.g., plethy* would include both plethysmograph and plethysmography): vaginal and sexual arousal; plethy* and (subjective or self-report*); plethy* and sexual arousal; photoplethy*; penile and (subjective or self-report); penile and sexual arousal; phallom* and (subjective or self-report); phallo* and sexual arousal; subjective and (physiolog* or psychophysiolog*); and (subjective and genital and arousal).

We included studies published in English and available in peer-reviewed journals, books or book chapters, theses, and dissertations. We did not include unpublished studies (e.g., unpublished manuscripts, conference presentations) because their data could not be easily obtained, verified, or examined by readers. The possibility of a publication bias was examined using a funnel graph. We note that concordance was rarely the main focus of the selected studies, and was instead reported as part of the statistical analyses that were conducted.

Some data sets were reported in more than one publication. In these cases, we coded the publication representing the largest amount of data (e.g., the publication reporting on the largest sample size). Data collection ended in December 2007.

Selection Criteria for Inclusion in the Meta-Analysis

Studies were included in this meta-analysis if they reported data from which the correlation between a self-reported and genital measure of sexual arousal in response to a specified sexual stimulus could be obtained and if they met several other criteria, as explained below.

Criterion 1: Self-Report Measure of Sexual Arousal

Studies had to employ a clearly specified measure of self-reported sexual arousal or subjective estimate of genital response. These included Likert-type ratings, ratings made with visual analog scales, estimates of percentage of full response, or moving levers or other devices to indicate sexual arousal. Subjective sexual arousal and estimated genital response were coded separately.

Criterion 2: Physiological Measure of Genital Arousal

A specific measure of genital sexual arousal had to be employed. For women, genital measures of sexual arousal included vaginal photoplethysmography or thermography. For men, genital measures of sexual arousal included circumferential assessments using mercury-in-rubber, indium-gallium, or mechanical (Barlow) strain gauges, volumetric devices, or thermography.

Criterion 3: A Well-Specified Sexual Stimulus

Self-reported and genital arousal had to be measured in response to some form of psychological sexual stimulation, including self-generated or guided sexual fantasy, exposure to visual sexual stimuli (pictures or film, with or without audio accompaniment), or descriptions of sexual interactions either read by the participant or presented as an audio recording.

Criterion 4: Correlation Coefficient Between Self-Reported and Genital Measures of Sexual Arousal

A correlation coefficient between self-reported and genital measures of sexual arousal had to either be reported in the published article, book chapter, book, thesis, or dissertation, or available from the primary authors. Correlations that were reported as statistically nonsignificant without reports of actual coefficient values were coded as zero.

For estimates of concordance between self-reported feelings of sexual arousal and genital response (hereinafter, Rsub), correlations for one male sample and sixteen female samples were described by the original authors as not statistically significant and therefore coded as zero. For estimates of concordance between self-reported genital response and actual genital response (hereinafter, Rgen), correlations for one male sample and two female samples were described as not statistically significant and therefore coded as zero. In one case, correlations were estimated from study figures (Schaefer, Tregerthan, & Colgan, 1976).

Studies Included in the Meta-Analysis

We identified 132 studies published between 1969 and 2007 reporting genital and self-reported sexual arousal responses, with total sample sizes of 2,505 women and 1,918 men. Of these studies, 70 reported on female samples, 49 reported on male samples, and 13 reported on both male and female samples.

Moderator Variables

As discussed earlier, we focused first on methodological variables that might be moderators of the agreement between self-reported and genital measures of sexual arousal on the basis of previous research. We then examined variables that might be potential moderators under the logic of hypotheses derived from sexual selection, information processing, and learning theories.

We were constrained in our variable selection by the study descriptions that were available in the published reports. For example, most of the studies that were included in this meta-analysis either did not record or report details about the participants’ sexual histories, or reported them in idiosyncratic ways that made meta-analysis impossible, so we could not code for sexual experience as a moderator of concordance, even though this would provide a clear and more direct test of our hypothesis about the impact of learning on concordance. Instead, we used participant age as a proxy for sexual experience, because older participants would have more sexual experiences, on average, than younger participants.

The study variables are described below, organized in a rational fashion, according to how the data were coded, that does not necessarily correspond to the study hypotheses. The results, however, are presented in the order in which the hypotheses are listed.

Sample Characteristics

Participant Age

Average participant age for the sample was recorded. If only an age range was provided, the mid-point of this range was selected to represent the sample’s average age.

Study Population

The population from which the study sample was recruited was coded as basic (sexually functional volunteers and pre-menopausal, if female), sexually dysfunctional persons, post-menopausal women, medical patients, sexual offenders, or clinical/sexological patients.

Hormonal Status

This moderator was coded only for female samples. Samples were coded as using oral contraceptives, no use of exogenous hormones (this was only coded when it was clearly stated that participants were not using oral contraceptives or receiving hormone replacement therapy), or unspecified.

Stimulus Characteristics

Stimulus Modality

Stimuli were assigned to the following categories: video/film presented with audio; video/film presented without audio; audiotaped description of sexual interaction; sexual fantasy; sexual text read by subject; still pictures; and still pictures presented with audiotaped descriptions of sexual interaction. Combinations of stimulus modalities were also recorded when correlations were reported in this manner (e.g., across video, fantasy, and still picture stimuli; across both video and audiotape stimuli; across both audiotape and fantasy stimuli).

Stimulus Duration

The total duration of stimulus presentation was recorded in seconds. This was equal to the duration of the stimulus if the study used a single presentation. If multiple sexual stimuli were used, and the correlation between self-reported and genital measures was reported across these stimuli, the total duration of all sexual stimuli was recorded in seconds.

Stimulus Sexual Explicitness

Stimulus content was coded for the explicitness of the sexual interactions presented or described. Stimuli were considered to be explicit if they included clear depictions of genital interactions during oral, anal, or vaginal intercourse. Stimuli showing sexual interactions that did not include depictions of oral, anal, or vaginal intercourse (e.g., a stimulus depicting kissing, touching, and other foreplay or included oral, anal, or vaginal intercourse scenes without clear depictions of the genitals) were coded as erotic.

Female-Centered Stimulus

Stimulus content was coded as female-centered, not female-centered, or missing (e.g., a fantasy stimulus). A stimulus was considered female-centered if it was explicitly described as female-centered or made for female audiences.

Number of Trials

The total number of stimulus trials was coded.

Stimulus Variability

The correlations reported by each study sample were coded as demonstrating stimulus variability if the correlation coefficient was calculated from a set of sexual stimuli that had at least two kinds of stimulus content (e.g., preferred and nonpreferred gender, preferred and nonpreferred activity) or at least two kinds of stimulus modality (e.g., audiovisual and sexual fantasy, still pictures and text).

Self-Reported Sexual Arousal

Two different measures of self-reported sexual arousal were coded. The first was self-reported subjective experience of sexual arousal (e.g., feeling “sexually excited,” “sexually aroused,” or “horny”). We refer to this as Rsub throughout this article. The second was a self-reported estimate or perception of genital response (e.g., a man estimating his erection during a stimulus presentation; a woman rating the intensity of felt genital sensations during a trial). We refer to this as Rgen throughout this article.

Timing

The timing of self-reported arousal assessments was coded as immediately after a stimulus presentation, contiguous with stimulus presentation, or after all sexual stimuli had been presented (end of session).

Genital Sexual Arousal Measurement

Apparatus

The methods of measuring genital sexual arousal differed between the sexes. For women, measures of genital sexual arousal included vaginal photoplethysmography (coded as VPA or VBV, depending on how the data were represented) or thermography (both pelvic and labial temperature changes). For men, measures of genital response included circumferential assessments using mercury-in-rubber, indium-gallium, and mechanical (Barlow) strain gauges, assessment of changes in penile volume, and thermography of the pelvic region.

Statistical Methods

These potential moderators included the type of correlation calculated and the number of data points used to calculate the correlation coefficient.

Type of Correlation

The type of correlation coefficient calculated in each study was coded. Within-subjects correlations address agreement across individual variation in responding, while between-subjects correlations address the agreement across group variation in responding. Mixed correlations are calculated across both participants and stimulus conditions and therefore represent a combination of both within-subjects and between-subjects data points.

Number of Data Points

For within-subjects correlations, the number of data points refers to the number of observations of subjective and genital response for each individual. For between-subjects correlations, the number of data points refers to the number of participants included in the analysis. For mixed correlations, the number of data points refers to the number of participants multiplied by the number of observations per participant.

Inter-Rater Reliability

The study coding was completed by the first and second authors. Twelve studies were randomly selected from the final set of studies and coded by both the first and second authors. Inter-rater coding was limited to study conditions representing basic participants, responses to preferred sexual stimuli, no experimental manipulations, and correlations calculated using average self-reported and genital sexual arousal responses (if more than one method of reducing data was reported).

Inter-rater reliability values ranged from good to excellent. Kappas for categorical variables ranged from 0.81 to 1.00, and Spearman’s rho for ordinal or interval variables ranged from .78 to 1.00. Kappa could not be calculated in some cases because the cross-tabulations of the two ratings were not symmetric. Inspection of these asymmetric categorical variables indicated percentages of agreement from 77% to 100%.

The entire data set was checked for errors by the fifth author, who was, at that time, masked to the study hypotheses. A total of 205 discrepancies were found, representing an average of 1.6 discrepancies per study (ranging from 0 to 24 discrepancies), and 0.7% of all possible cells. Discrepancies were resolved in discussions with the first author, and consultation with the second author if necessary.

Effect Size and Analytical Strategy

We used Pearson r as our index of effect size, representing the correlation between subjective and genital sexual arousal (or the correlation between perception of and actual genital arousal, in the case of Rgen). We first examined the overall gender difference by comparing the r obtained for all correlations reported for men and for women. We then examined the gender difference in r for each independent sample. For this analysis, we averaged across all correlations obtained for each sample, using Fisher’s r to z transformation, and transforming back to r. We next examined the correlation between subjective and genital sexual arousal for a selected subset of independent samples (defined below). Finally, we examined subjective-genital agreement in the 13 studies that directly compared male and female samples. We conducted this nested series of analyses to determine if a gender difference in concordance could be reliably detected regardless of how studies were selected.

For analyses involving moderator variables coded in a discrete fashion, an average correlation for each independent sample, at each level of the moderator variable, was calculated. For analyses involving moderator variables coded in a continuous fashion, a correlation was calculated between the putative moderator and the concordance estimate obtained using all relevant independent samples.

Ninety-five percent confidence intervals were calculated to examine gender and moderator differences, and to test if correlations were significantly different from zero. The rule for determining whether a categorical variable difference was statistically significant was that one mean had to be outside of the 95% confidence interval of the other mean; for example, there was a significant difference between male samples and female samples if the mean subjective-genital correlation of either gender did not fall within the 95% confidence interval of the other gender. All analyses were weighted by sample size, so that studies with larger samples had more influence on the average subjective-genital correlation. The Fisher z inverse variance method was used to calculate aggregate correlations, with a random-effect model. Comprehensive Meta-Analysis v1.0.25 (Biostat Inc., Englewood, NJ) and SPSS version 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) were used for all statistical analyses.

Results

Table 1 summarizes each study included in the meta-analysis. Details included sample characteristics, measures of subjective and genital sexual arousal, and the average correlation between these measures of sexual arousal.

Table 1.

Summary of studies included in meta-analysis

| Study | Sample description | Measures | Study design | Stimuli | Correlation with self-reported sexual arousal | Correlation with perception of genital arousal | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | Genital | Subjective | Female | Male | Female | Male | |||

| Studies reporting within-subjects correlations | ||||||||||

| Abel, Blanchard, Murphy, Becker, and Djenderedjian (1981) | – | 21 volunteers (mean age = 24) | Barlow gauge | Likert | Compared two methods of quantifying penile response: percent of full erection and AUC (area under penile response curve). | 12 explicit presentations of deviant and non- deviant film and audio. | – | .74/.67 (% erection/ AUC) | – | .82/.82 (% erection/AUC) |

| 6 outpatients (mean age missing) | 24 explicit presentations of homosexual and heterosexual film, audio, and fantasy. | – | .68/.74 | – | .88/.83 | |||||

| 8 sex offenders (mean age missing) | 24 explicit presentations of deviant and nondeviant film, audio, and fantasy. | – | .57/.56 | – | .78/.75 | |||||

| Abrahamson, Barlow, Beck, and Athanasiou (1985) | 10 volunteers (mean age = 39.5) | Barlow gauge | Lever | Effects of distraction and stimulus intensity on functional and dysfunctional men. | 3 explicit film clips. | – | .61 | – | – | |

| 10 with erectile dysfunction (mean age = 43.6) | Correlations reported across distraction and film conditions. | – | .32 | – | – | |||||

| Bancroft (1971) | 25 combined heterosexual & homosexual sexology patients (mean age missing) | Strain gauge | Likert | Sexual response to preferred and nonpreferred sexual stimuli | 10 slides (5 nude male and 5 nude female). | – | .74 | – | – | |

| Barlow, Sakheim, and Beck (1983) | 12 students (mean age = 26.3) | Barlow gauge | Lever | Effect of anxiety induced by shock threat. Correlation reported for no-shock condition. | 1 explicit film. | – | .68 | – | – | |

| Beck and Barlow (1986) | 12 with secondary erectile dysfunction (mean age = 43.8) | Barlow gauge | Lever | Effect of attentional focus and anxiety (induced by shock threat). | 4 explicit heterosexual films of foreplay. | – | .70 (no shock threat) | – | – | |

| 12 volunteers (mean age = 40.9) | Correlations reported across focus conditions (sensate and spectator focus) and group. | – | .52 (shock threat) | – | – | |||||

| Beck, Barlow, and Sakheim (1983) | 8 volunteers (mean age = 35) | Barlow gauge | Lever | Effects of attentional focus (self versus partner). | 6 explicit black-and-white heterosexual films of foreplay. | – | .23 | – | – | |

| 8 with sexual dysfunction (mean age = 42) | Correlations reported across focus conditions. | – | .13 | – | – | |||||

| Beck, Barlow, Sakheim, and Abrahamson (1987) | 16 volunteers (mean age = 24) | Barlow gauge | Lever | Effects of shock threat, selective attention, thought content and affect. | 4 explicit heterosexual audiotaped clips. | – | .75 | – | – | |

| Correlations reported across shock conditions. | – | – | – | – | ||||||

| Chivers et al. (2007) | 27 heterosexual students & volunteers (mean age = 22.3) | 27 heterosexual students & volunteers (mean age = 24) | VPA/Strain gauge | Lever | Gender and orientation differences in response to sexual activities vs. gender of actors in sexual films. | 16 film clips (mating bonobos, nude exercise, masturbation & copulation clips). | .51 | .82 | – | – |

| 20 homosexual students & volunteers (mean age = 28) | 17 homosexual students & volunteers (mean age = 25.1) | Correlations reported across several stimuli. | .56 | .85 | – | – | ||||

| Cranston-Cuebas et al. (1993) | 10 volunteers (mean age = 43.9) | Barlow gauge | Lever | Effects of misattribution manipulation using placebo. | 3 explicit heterosexual films depicting 2 females, 1 male. | – | .23 | – | – | |

| 10 with secondary erectile dysfunction (mean age = 48.8) | Correlations reported across manipulation conditions (detraction, enhancement, neutral). | – | .45 | – | – | |||||

| Dekker and Everaerd (1988) | 48 students (mean age = 22) | 48 students (mean age = 23) | Barlow gauge | Likert | Attentional effects on sexual arousal. | 15 explicit heterosexual slides, one audiotaped narrative, and sexual fantasy. | – | .43 | – | – |

| VPA | Correlations averaged across stimuli and focus conditions (focus on situation/action and focus on sexual response). | .37 | – | – | – | |||||

| VBV | .16 | – | – | – | ||||||

| Farkas, Sine, and Evans (1979) | 30 students (mean age = 26.4) | Strain gauge | Lever | Effects of distraction, performance demand and stimulus explicitness on sexual arousal. | 1 explicit or nonexplicit (clothed, heterosexual sensual interaction) black-and-white film without audio. | – | .49 (attention) | – | – | |

| – | .35 (distraction) | – | – | |||||||

| Korff and Geer (1983) | 10 students (mean age missing) | VPA | Visual-auditory scale | Relationship between focus condition and concordance. | 10 erotic heterosexual slides. | .48/.47/.69 (scale/light/tone) | – | – | – | |

| 12 students (mean age missing) | Correlations for 3 subjective scales: 5-point rating, light, and sound (tone). | 10 erotic heterosexual slides. | .87/.82/.90 | – | – | – | ||||

| Genital focus group. | ||||||||||

| 14 students (mean age missing) | Non-genital focus group. | 10 erotic heterosexual slides. | .86/.82/.79 | – | – | – | ||||

| Laan and Everaerd (1995b) | 16 students (mean age = 21) | VPA | Lever | Habituation of sexual arousal. | 11 slides, depicting heterosexual sex and nude or semi-nude male or female models. | .38 | – | – | – | |

| 19 students (mean age = 20.5) | 21 explicit heterosexual films (female-centered). | – | – | .28 | – | |||||

| 20 students (mean age = 20.5) | 21 uniform presentations of a cunnilingus scene. | – | – | .24 | – | |||||

| Laan, Everaerd, van der Velde et al. (1995) | 17 students (mean age = 20) | VPA | Lever | Association between subjective and genital arousal. | 21 presentations of explicit, heterosexual film clip (female-centered). | – | – | .26 | – | |

| 14 students (mean age = 20) | 21 explicit heterosexual film clips (female-centered). Clips were different but showed the same content. | – | – | .30 | – | |||||

| 19 students (mean age = 20) | 21 explicit heterosexual film clips (female-centered), increasing in sexual intensity. | – | – | .61 | – | |||||

| Mavissakalian et al. (1975) | 6 heterosexual students (mean age = 22.6) | Barlow gauge | Lever | Responses to erotic stimuli in homosexual and heterosexual males. | 16 explicit black-and-white film clips, depicting heterosexual activity, single female activity, homosexual male or lesbian activity. | – | .69/.74 (within/between) | – | – | |

| 6 homosexual sexology patients (mean age = 21.5) | Correlations reported across two sessions as within-subjects and between-subjects. | – | .70/.57 | – | – | |||||

| Meuwissen and Over (1992) | 10 students (mean age = 26.9) | VPA/VBV | Likert | Correlation between subjective and genital arousal across phases of menstrual cycle. | 9 explicit film clips and 15 fantasies. Film varied in content and target stimuli. Fantasy varied in content and included atypical sex. | .62 /.69 (menstrual) | – | – | – | |

| .72/.69 (post-menstrual) | – | – | – | |||||||

| Correlations calculated across all 24 stimulus trials for each phase. | .60/.68 (luteal) | – | – | – | ||||||

| .69/.73 (pre-menstrual) | – | – | – | |||||||

| Rellini et al. (2005) | 22 volunteers (mean age = 27) | VPA | Likert | Relationship between physiological and subjective arousal in women. | 1 explicit heterosexual film. | −.08 | – | −.13 | – | |

| Rowland and Heiman (1991) | 9 volunteers (mean age = 36.1) | Strain gauge | Likert | Arousal before (Time 1) and after (Time 2) sex therapy program. | 2 explicit heterosexual audiotapes, narrated by female. | – | .74/.81 (time 1/time 2) | – | .80/.72 (time 1/time 2) | |

| 9 with sexual dysfunction (mean age = 41.8) | – | – | Correlations reported across sensate focus and instructional demand. | Unstructured fantasy. | – | .61/.73 | – | .67/.52 | ||

| Rubinsky et al. (1985) | 6 volunteers (mean age = 28) | 10 volunteers (mean age = 28) | VPA or strain gauge | Likert | Testing validity of groin skin temperature. | 1 explicit black-and-white heterosexual film. | .09 | .43 | – | – |

| VBV | .53 | – | – | – | ||||||

| Thermography | .63 | .31 | – | – | ||||||

| Sakheim, Barlow, Abrahamson, and Beck (1987) | 10 healthy volunteers (mean age = 38.1) | Barlow gauge | Lever | Distinguishing between psychogenic and organogenic erectile dysfunction. | 1 explicit heterosexual film clip. | – | – | – | .72 | |

| 10 with psychogenic sexual dysfunction (mean age = 44.6) | – | – | – | .50 | ||||||

| 10 with organogenic sexual dysfunction (mean age = 55.8) | – | – | – | .26 | ||||||

| Strassberg, Kelly, Caroll, and Kircher (1987) | 13 volunteers (mean age = 30) | Barlow gauge | Likert | Sexual arousal and premature ejaculation. | 3 explicit film clips. | – | .54 | – | – | |

| 13 with premature ejaculation (mean age = 33) | – | .49 | – | – | ||||||

| Webster and Hammer (1983) | 8 heterosexual volunteers (mean age = 27) | Barlow gauge | Likert | Thermographic measurement of arousal. | 3 explicit heterosexual film clips (black and white). | – | .95 | – | – | |

| Thermography | – | .94 | – | – | ||||||

| Wincze, Hoon, and Hoon (1977) | 6 volunteers (mean age = 24.3) | – | VPA | Likert | Comparing cognitive and physiological responses. | 17 explicit film clips, depicting heterosexual intercourse, group sex and single homosexual scene. | .41 | – | – | – |

| Thermography | .27 | – | – | – | ||||||

| Wincze et al. (1980) | 8 volunteers (mean age = 22.2) | 6 volunteers (mean age = 20.6) | VPA or Barlow gauge | Likert | Effects of subjective monitoring. | 2 heterosexual film clips, depicting low arousal (kissing) and high arousal (intercourse). | .15 | .69 | – | – |

| Correlations reported across arousal conditions. | ||||||||||

| Wincze and Qualls (1984) | 8 homosexual volunteers (mean age = 26) | 8 homosexual volunteers (mean age = 26) | VPA or Barlow gauge | Likert | Sexual orientation and sexual arousal to preferred and nonpreferred sexual stimuli. | 5 explicit films depicting female–male sex, male–male sex, female–female sex, group sex and neutral. | .69 | .86 | – | – |

| Wormith (1986) | – | 36 combined sex offenders and non-sex offenders (mean age = 30.2) | Strain gauge | Likert | Physiological and cognitive aspects of deviant sexual arousal. Correlations reported across content conditions. | 12 explicit slides, depicting adult male, adult female, child male, child female, heterosexual couple and neutral scene. | – | .53 | – | – |

| Studies reporting between-subjects correlations | ||||||||||

| Abramson et al. (1981) | 37 students (mean age = 28) | 32 students (mean age = 28) | Thermography | Likert | Discriminant validity of thermography. | 1 explicit story. | .70 | .73 | – | – |

| Adams et al. (1985) | 24 students (mean age = 20.1) | VPA | Likert | Effect of cognitive distraction. | 1 explicit heterosexual audiotape. | – | – | .37 (no distraction) | – | |

| – | – | .74 (distraction) | – | |||||||

| Adams, Wright, and Lohr (1996) | 64 students (mean age = 20.3) | Strain gauge | Likert | Homophobia and sexual arousal. | 1 explicit heterosexual film. | – | .57 | – | .64 | |

| 1 explicit female–female film. | – | .63 | – | .66 | ||||||

| 1 explicit male–male film. | – | .53 | – | .64 | ||||||

| Bach et al. (1999) | 26 volunteers (mean age = 32.2) | Barlow gauge | Likert | False negative feedback and sexual arousal. | 2 explicit heterosexual films with no audio. | – | .29 (film 1) | – | .28 (film 1) | |

| – | −.16 (film 2) | – | .37 (film 2) | |||||||

| Basson and Brotto (2003) | 34 post-menopausal with sexual dysfunction (mean age = 56.6) | VPA | Likert | Drug trial for sildenafil citrate. | 1 explicit heterosexual film. | .19 | – | .30 | – | |

| Bellerose and Binik (1993) | 58 combined volunteers, hysterectomy & oophorectomy patients (mean age = 46) | VPA | Likert | Body image and sexuality in oophorectomized women. | 1 explicit heterosexual film. | .23 | – | .28 | – | |

| Lever | Correlations reported across two sessions. | .24 | – | .28 | – | |||||

| Bernat, Calhoun, and Adams (1999) | 34 students (mean age = 19.9) | Strain gauge | Likert | Arousal to consensual and nonconsensual sex. | 2 explicit audiotaped clips paired with nude female slide. | – | – | – | .64 | |

| Both et al. (2004) | 10 students (mean age = 22.6): Study 1 | 10 students (mean age = 22) | VPA or Barlow gauge | Likert | Sexual behavior (study 1) and responsiveness to stimuli (study 2) following laboratory-induced sexual stimulation. | 1 explicit heterosexual film. | −.26 | .45 | .13 | .60 |

| 24 students & volunteers (mean age = 24.5): Study 2 | 24 students & volunteers (mean age = 27) | −.02 | .03 | −.06 | −.06 | |||||

| Both, Everaerd, Laan, and Gooren (2005) | 28 students (mean age = 22) | 19 students (mean age = 22) | VPA or Barlow gauge | Likert | Effects of dopamine on arousal in men vs. women. | 2-min fantasy period (unstructured). | .13 | .67 | .16 | .65 |

| 1 explicit heterosexual film. | .31 | .49 | .16 | .68 | ||||||

| Both, Van Boxtel, Stekelenburg, Everaerd, and Laan (2005) | 26 students (mean age = 22.9) | VPA | Likert | Spinal reflexes and arousal to films of increasing intensity. | 1 low-intensity heterosexual film (kissing). | −.23 | – | .12 | – | |

| 1 medium-intensity heterosexual film (kissing & caressing). | .30 | – | .37 | – | ||||||

| 1 high-intensity heterosexual film (intercourse). | .20 | – | .04 | – | ||||||

| Bradford and Meston (2006) | 38 volunteers (mean age = 25.4) | VPA | Likert | Effect of anxiety. | 1 explicit heterosexual film. | .35 | – | .32 | – | |

| Brauer et al. (2006) | 24 volunteers (mean age = 26.6) | VPA | Likert | Arousal to coital vs. non-coital sex in women with dyspareunia. | 1 explicit heterosexual film depicting oral sex. | .43/.25/.31 (oral/coitus/average) | – | .43/.37/.43 (oral/coitus/average) | – | |

| 48 with dyspareunia (mean age = 28.2) | Correlations reported for oral film, coitus film, or average across both films. | 1 explicit heterosexual film depicting coitus. | −.14/.21/.03 | – | .00/.27/.15 | – | ||||

| Brauer et al. (2007) | 48 volunteers (mean age = 23.9) | VPA | Likert | Pain-related fear and dyspareunia. | 1 explicit heterosexual film. | .18 | .24 | – | – | |

| 48 with dyspareunia (mean age = 25.9) | −.05 | .12 | – | – | ||||||

| Briddell et al. (1978) | 48 heterosexual students (mean age = 22) | Strain gauge | Likert | Effects of alcohol and cognitive set. | 1 explicit heterosexual audiotape (consensual). | – | .57 | – | .73 | |

| 1 explicit audiotape of forcible rape scenario. | – | .42 | – | .56 | ||||||

| Fantasy. | – | .55 | – | .60 | ||||||

| Briddell and Wilson (1976) | 48 students (mean age = 20) | Strain gauge | Likert | Effects of alcohol and alcohol expectancy. | 2 explicit heterosexual films. | – | – | – | .66 | |

| Correlations reported across four alcohol and two expectancy conditions. | – | – | – | – | ||||||

| Brotto and Gorzalka (2002) | 25 pre-menopausal (mean age = 24.5) | VPA | Likert | Effects of hyperventilation on sexual arousal in pre- and postmenopausal women. | 1 explicit heterosexual film. | .14 | – | .19 | – | |

| 21 pre-menopausal (mean age = 47.8) | Correlations reported across two sessions. | .42 | – | .48 | – | |||||

| 25 post-menopausal (mean age = 56) | .26 | – | .30 | – | ||||||

| Brotto et al. (2004) | 30 volunteers (mean age = 23.4) | VPA | Likert | Patterns of sexual response in sexually dysfunctional women. | 1 explicit heterosexual film. | −.38 | – | −.22 | – | |

| 31 with sexual dysfunction (mean age = 30.6) | .17 | – | .08 | – | ||||||

| Cerny (1978) | 10 students given no feedback (mean age = 19.9) | VBV/VPA | Likert | Biofeedback and voluntary control. | 1 explicit heterosexual film. | .72/.00 (nonsig) | – | – | – | |

| 10 students given accurate feedback (mean age = 19.9) | Correlations reported across 10 trials. | .00/.00 (nonsig) | – | – | – | |||||

| 10 volunteers given false feedback (mean age = 19.9) | .00/.00 (nonsig) | – | – | – | ||||||

| Chivers (2003) | 69 heterosexual volunteers (mean age = 24.6) | 39 heterosexual volunteers (mean age = 29.6) | VPA or strain gauge | Likert | Relationship between sexual arousal to preferred and nonpreferred sexual stimuli and sexual orientation. | 3 explicit film clips depicting gay, lesbian, or heterosexual sex. | .36/.52/.41 (gay/lesbian/heterosexual) | .58/.48/.51 | – | – |

| 19 homosexual volunteers (mean age = 28.4) | 29 homosexual volunteers (mean age = 32.7) | .57/.59/.49 | .55/.67/.41 | – | – | |||||

| 17 bisexual volunteers (mean age = 25.1) | 30 bisexual volunteers (mean age = 29.6) | .39/.55/.56 | .08/.48/.19 | – | – | |||||