Abstract

Naïve dialecticism refers to a set of East Asian lay beliefs characterized by tolerance for contradiction, the expectation of change, and cognitive holism. In five studies, the authors examined the cognitive mechanisms that give rise to global self-concept inconsistency among dialectical cultures. Contradictory self-knowledge was more readily available (Study 1) and simultaneously accessible (Study 2) among East Asians (Japanese and Chinese) than among Euro-Americans. East Asians also exhibited greater change and holism in the spontaneous self-concept (Study 1) and inconsistency in their implicit self-beliefs (Study 3). Cultural differences in self-concept inconsistency were obtained when controlling for alternative explanatory variables, including self-criticism (Study 4) and self-concept certainty (Studies 2 and 3) and were fully mediated by a direct measure of dialecticism (Study 5). Naïve dialecticism provides a comprehensive theoretical framework for understanding these cultural differences and the contradictory, changeable, and holistic nature of the East Asian self-concept.

Keywords: self-concept, self-perception, implicit beliefs, cross-cultural differences, East Asians

The self is a cognitive structure that is influenced greatly by cultural factors. Most of the cross-cultural research on the self-concept has emerged from the value tradition, which focuses on individualism–collectivism (Triandis, 1995), and the self tradition, which emphasizes cultural differences in self-construals (Markus & Kitayama, 1991). The present research examines naïve dialecticism (Peng & Nisbett, 1999), a cultural dimension grounded in the lay theory tradition, and the contradictory, changeable, and holistic nature of the East Asian self-concept.

A lengthy description of naïve dialecticism is beyond the scope of this article (see Peng & Nisbett, 1999; Spencer-Rodgers & Peng, 2004), but we briefly describe its three main concepts. The theory of change asserts that the universe is unpredictable, dynamic, and in constant flux. The theory of contradiction holds that two ostensibly contradictory propositions may both be true simultaneously (yin–yang). The third feature of naïve dialecticism is holism, or the notion that the part cannot be understood except in relation to the whole. Members of dialectical cultures attend more to the perceptual field as a whole, whereas members of Western cultures are more object focused and field independent (Peng & Nisbett, 1999). All phenomena in the universe, including the self, are seen as interconnected and mutually dependent. Thus, from a dialectical perspective, the “individual self” is not only interconnected with other people, such as important ingroup members, but also with all material objects and spiritual forces in the universe.

A principal consequence of naïve dialecticism is that East Asians more comfortably accept psychological contradiction. This arises when two or more opposing elements (e.g., love–hate) do not easily coexist within the psyche, even though the constructs themselves are not logically contradictory. For instance, Chinese participants with “dialectical self-esteem” conceive of themselves as both good and bad simultaneously (Spencer-Rodgers, Peng, Wang, & Hou, 2004), and East Asians exhibit greater internal inconsistency in their affective and well-being judgments (e.g., Schimmack, Oishi, & Diener, 2002). Although East Asians do experience cognitive dissonance when making incongruent choices for important others (Hoshino-Browne et al., 2005) or when faced with social disapproval (Kitayama, Snibbe, Markus, & Suzuki, 2004), they are generally less troubled by contradiction in their private, self-relevant thoughts, emotions, and behaviors (Heine & Lehman, 1997). Conversely, Westerners (particularly Euro-Americans) seek to reconcile inconsistencies; they are more “synthesis oriented” in that discrepancies in their cognitions, emotions, or behaviors give rise to a state of tension (Lewin, 1951), disequilibrium (Heider, 1958), or dissonance, which activates a need for consonance (Festinger, 1957).

The present research focuses on the internal consistency of the content of one's global self-beliefs or “personality,” a topic that has received less attention in the literature than cross-cultural research on contradiction in emotion and well-being. Moreover, previous cross-cultural studies that have focused on personality consistency/coherence have emphasized the cross-situational consistency of the self. For example, English and Chen (2007) showed that Asian Americans hold internally consistent, context-specific self-beliefs (e.g., self-at-home, self-at-school). Other studies have documented that East Asians use more situational modifiers when characterizing the self (Cousins, 1989), view themselves more flexibly across situations (Suh, 2002), and describe themselves differently on the Twenty Statements Test (TST; Kuhn & McPartland, 1954) depending on the context (e.g., when alone, with a group; Kanagawa, Cross, & Markus, 2001). Self-concept consistency is also less central to psychological well-being among East Asians than North Americans (Heine & Lehman, 1999; Suh, 2002). The present research focuses on the internal consistency of global self-knowledge (i.e., the extent to which contradictory self-beliefs are held simultaneously) rather than cross-situational consistency or context-specific self-beliefs. Given the central role that the assumption of internal consistency plays in many Western personality and self theories (e.g., self-verification theory; Swann, Rentfrow, & Guinn, 2003), testing the cultural relativity of this assumption is important.

One study that examined the internal consistency of the global self-concept showed that Koreans exhibit less internal consistency regarding their personality characteristics and value judgments than do Americans (Choi & Choi, 2002). This early work on the “dialectical self” (Spencer-Rodgers & Peng, 2004) raises several intriguing and as yet unanswered questions, which we address. Specifically, we examine the cognitive mechanisms that underlie cultural differences in global self-concept inconsistency. Higgins (1996) offered the useful distinction between the availability and accessibility of self-knowledge. Whereas availability refers to whether knowledge is represented in memory, accessibility refers to how readily knowledge is activated and used in some interpretive task. Perhaps because of naïve dialecticism, East Asians have more contradictory self-knowledge stored in memory than do Euro-Americans. We tested this possibility in Study 1. Contradictory self-knowledge may also be more accessible among East Asians than among Westerners. The possibility that contradictory self-knowledge is more simultaneously accessible (i.e., brought to mind quickly, and equally quickly) among Japanese relative to Euro-Americans was tested in Study 2. Another question we sought to address is whether Chinese show greater contradiction in their implicit self-beliefs than do Euro-Americans (Study 3).

An additional purpose of the research was to show that dialecticism (tolerance for contradiction) makes a unique contribution to cultural differences in global self-concept inconsistency beyond what can be explained by cultural variation in self-criticism and self-concept certainty. Previous research on the dialectical self has relied almost exclusively on explicit, untimed paper-and-pencil measures, which are susceptible to social desirability and cultural differences in self-presentation. An important factor to consider when examining dialectical responses is valence. East Asians may describe themselves in a more contradictory manner, in part, because they tend to be critical of themselves (Heine & Hamamura, 2007). Although trait content and trait valence are theoretically distinct, in actuality, contradictory traits also tend to be oppositely valenced (e.g., organized–disorganized; Hampson, 1998). Hence, the tendencies to endorse semantic opposites (e.g., organized and disorganized) and traits of negative valence (e.g., disorganized) are naturally confounded, and cultural differences in self-concept inconsistency are likely to be due in part to the East Asian proclivity toward self-criticism (Spencer-Rodgers et al., 2004). To examine whether cultural differences in global self-concept inconsistency remain significant beyond a tendency to endorse negative self-descriptors, in all studies we computed an index of self-criticism and repeated our main analyses controlling for self-criticism. In addition, in Study 4 we examined self-criticism directly by having participants rate the valence of trait adjectives and using these ratings as a measure of self-criticism. East Asians may also exhibit less internally consistent self-conceptions because they are less certain of their standing on personality traits (Campbell et al., 1996). Studies 2 and 3 showed that our effects remain when controlling for self-certainty. Finally, Study 5 demonstrated that a direct measure of naïve dialecticism (Dialectical Self Scale [DSS]; Spencer-Rodgers et al., 2008) mediates cultural differences in self-concept inconsistency.

STUDY 1

As outlined previously, prior research has shown that East Asians tolerate greater contradiction in their emotions, personality/trait judgments, and attitudes than do Euro-Americans. In Study 1, we examined one mechanism that gives rise to global self-concept inconsistency. Specifically, we tested whether a greater amount of contradictory self-knowledge is available among Chinese than among Euro-Americans. To do so, we examined the internal consistency of the spontaneous self-concept using the TST, an open-ended instrument that is relatively culturally unbiased, as participants report spontaneously the content of their self-beliefs (Kanagawa et al., 2001). We predicted that a greater amount of inconsistent self-knowledge would be retrieved from memory among Chinese in response to the stimulus question, “Who am I?”

In addition to examining self-concept inconsistency, we investigated whether Chinese would spontaneously report more dynamic (i.e., change-oriented) and holistic self-descriptions on the TST than would Euro-Americans. Participants' responses were coded according to the Dialectical Coding Scheme (DCS). The DCS is a theory-driven protocol that consists of three main categories corresponding to the dimensions of contradiction, change, and holism. These categories differ substantially from those employed in previous cross-cultural research on the self (e.g., Cousins, 1989; Kanagawa et al., 2001). For instance, the TST has not been used to investigate the internal consistency of self-beliefs or holistic self-beliefs. In accordance with naïve dialecticism, we predicted that Chinese would spontaneously report a greater proportion of contradictory, dynamic, and holistic self-statements than would Euro-Americans.

An additional purpose of the study was to provide preliminary evidence that our findings are not due solely to self-criticism. We expected that cultural differences in the dialectical categories (proportions of contradictory, dynamic, and holistic self-statements) would hold, even when controlling for self-criticism.

Method

Participants

The 95 Chinese and 97 Euro-American participants (65 women; Mage = 21.3) were students at Peking University and the University of California (UC), Berkeley, respectively, who volunteered or participated for course credit.1

DCS

Participants' responses were coded for three types of contradiction (see Table 1). Psychological contradiction can be reflected within a single self-statement (e.g., “I am young, yet old at the same time”), which represents a balance between two contradictory self-conceptions. Contradiction can also be observed between statements either because they are logically contradictory (e.g., “I am hardworking” vs. “lazy”) or conceptually complementary (e.g., “I am usually hardworking” vs. “I sometimes procrastinate”). These between-statement contradictions were paired and the total number of pairs was computed for each participant. Statements conveying what a person is not were coded as a third type of contradiction. These responses are indicative of dialecticism in that the self is defined through the negation of an opposing self-view (Kitayama & Markus, 1999). The majority of these self-descriptions include the word not; however, the not-self can also be expressed in terms of a past role, identity, and so on (e.g., “I am an ex-girlfriend”).

TABLE 1.

Dialectical Coding Scheme

| Category | Example |

|---|---|

| Contradiction | |

| Within statement | I am friendly, but shy; I am enthusiastic and depressed about life; I am lazy and a hard worker at times; I am a pebble, small yet strong. |

| Between statement | I am easily stressed out & I am able to remain calm in any situation; I am practical & I am a dreamer; I am caring & I am sometimes selfish; I am hopeful & I am pessimistic. |

| Not-self-statement | I am not a good student; I am not from a wealthy family; I am an ex-smoker. |

| Change | |

| Dynamic statement | Recent change: I am a new student at Berkeley; I had a girlfriend; I am fatter than I used to be. |

| Ongoing change: I am a teacher-in-training; I am learning to ski; I am deciding what classes to take. | |

| Active state of being: I am new; I am living; I am searching. | |

| Anticipated change: I am going home after this; I am going to be 19 years old in April; I am going to be a doctor; I am a prospective graduate student. | |

| Desired change: I am in search of a girlfriend; I want a family. | |

| Contemplated change: I am thinking of volunteering at a clinic. | |

| Temporal modification | I am sometimes wasteful with money; I am grumpy in the morning; I am hungry right now; I am too driven at times. |

| Situational modification | I am stressed out at school; I am shy around people I don't know very well. |

| Qualitative modification | I am somewhat outgoing; I am a little bit selfish; I am fairly short. |

| Holism | |

| Holistic statement | I am someone insignificant in the universe; I am a mortal person; I am a Homo sapiens; I am a living form. |

We reasoned that the theory of change would be reflected in an increased tendency among Chinese to list dynamic self-statements on the TST. This broad category includes any response that indicates some type of transition (e.g., recent, ongoing, or desired change) in one's personality traits, physical characteristics, goals, and so on. For example, the response “I am someone who tries hard not to lie” represents a dynamic self-statement relative to the static self-statement “I am honest.” This category also includes self-statements pertaining to immediate changes in the situation (e.g., “I am going home after this”) and longer term changes, such as those related to personal growth (e.g., “I am growing”).

The theory of change is also reflected in self-descriptions that are modified with respect to time, place, or degree. The temporal modification category includes any response that conveys some type of temporal discontinuity, for example, in one's physical characteristics (e.g., “I am fatter now”) and goals/activities (e.g., “I am moving today”). The situational and qualitative modification categories include any response that reflects contextual variability (“I am outgoing when …”) or modification with respect to degree (e.g., “I am somewhat shy …”). If phenomena in the universe are constantly changing, including the self, strong, definite self-descriptions (e.g., “I am extremely outgoing”) are likely to be avoided.

Holistic self-statements include responses that recognize the interconnectedness among all things, including the self. These self-statements acknowledge that the individual self is a relatively insignificant part of a larger collective (e.g., “I am one but many”) and that human beings are connected to other living forms through a shared biological nature (e.g., “I am a biological entity above all”). They reflect dialectical folk theories of interconnection and a recognition that the individual self is an inseparable part of a larger whole.

The statements were coded by three bilingual research assistants (one Chinese, two U.S. natives). Statements could be given multiple codes (e.g., “I am trying to succeed, but I sometimes fail” was coded as within-statement contradiction, dynamic self-statement [signified by trying], and temporal modification [signified by sometimes]). The responses were also coded for valence (−1, 0, 1), and the proportions of positive and negative self-statements were computed for each participant. An index of self-criticism was then computed as follows: (number of negative self-statements – number of positive self-statements)/(number of negative self-statements + number of positive self-statements). The coders worked independently and were blind to the study hypotheses.

Results

Table 2 presents the mean percentages and level of coder agreement (indexed by Cronbach's alphas) by culture. As anticipated, Chinese listed a greater proportion of contradictory self-statements (total contradiction), change-oriented self-statements (total change), and holistic self-statements than did Euro-Americans. Specifically, Chinese cited significantly more dynamic self-statements, qualitative modifications, contradictory pairs, not-self-statements, and holistic self-statements than did Euro-Americans.2

TABLE 2.

Mean Percentages of Category Usage by Culture

| China | U.S. | Alpha | F | P < | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Change | |||||

| Dynamic statement | 13.0 | 4.2 | .92 | 38.85 | .001 |

| Temporal modification | 2.6 | 2.4 | .98 | < 1 | ns |

| Situational modification | 0.2 | 0.6 | .84 | 3.66 | .06 |

| Qualitative modification | 2.1 | 0.9 | .87 | 3.53 | .05 |

| Total change | 17.9 | 8.1 | .93 | 15.12 | .001 |

| Contradiction | |||||

| Within statement | 0.5 | 0.2 | .66 | < 1 | .17 |

| Between statement | 4.3 | 2.4 | .81 | 4.77 | .05 |

| Not-self-statement | 12.7 | 2.3 | .93 | 92.73 | .001 |

| Total contradiction | 17.4 | 4.9 | .90 | 85.54 | .001 |

| Holism | |||||

| Holistic statement | 0.7 | 0.1 | .79 | 7.30 | .01 |

NOTE: df = 190. Cronbach's alpha computed as level of agreement among the three coders.

When the index of self-criticism was entered as a covariate in the DCS analyses, all cultural differences remained significant except the ratio of qualitative modifications, F < 1. Only one variable was affected by this control procedure, which supports our assertion that the greater self-concept inconsistency, change, and holism of Chinese is not simply due to cultural variation in self-criticism.

Discussion

As predicted, more contradictory self-knowledge is available among Chinese than among Euro-Americans. When participants respond to the question “Who am I?” different aspects of the working self-concept are activated (McGuire & Padawer-Singer, 1976). A larger number of alternative self-images were brought to mind, as was reflected in the significantly larger proportion of contradictory pairs and not-self-statements listed by Chinese. Whereas Euro-Americans demonstrate a preference for direct and affirmative self-descriptions (e.g., “I am outgoing”), Chinese frequently define the self through the negation of an opposing self-conception (e.g., “I am not shy”). In discourse theory, this epistemological device is known as definition by negation (Lausberg, 1998). This finding suggests that a greater amount of contradictory self-knowledge is retrieved spontaneously from memory among Chinese. (An alternative self-image must have been brought to mind for that self-image to have been negated.)

The spontaneous self-concept was also characterized by greater change and holism among Chinese than among Euro-Americans. Chinese participants listed a greater proportion of dynamic self-statements than did Euro-Americans. Their responses reflected more recent and ongoing changes, active states of being, and anticipated, desired, and contemplated changes. Likewise, as predicted, Chinese listed more holistic self-statements than did Euro-Americans. Dialecticism defines the self as an inseparable part of a larger whole, which includes all material and spiritual phenomena. Although the dialectical self is constantly changing, the self is continuously referenced to some type of context. That context may be very narrow (e.g., the family unit, the immediate situation), or it may be very broad, so broad as to encompass all living and nonliving things (e.g., all of humanity, the universe). Self-statements such as “I am one but many” recognize that the individual self is part of a complex web of social and physical relationships. It is well established that East Asians and members of other interdependent cultures exhibit greater interconnectedness between the self and other people (Markus & Kitayama, 1991); however, the self-construal model makes no predictions beyond the interpersonal realm (i.e., associations between the self and other human beings). In accordance with the Taoist philosophy of holism, we found that Chinese also exhibit greater interconnectedness between the self, other living organisms, inanimate objects, and the metaphysical realm.

Interestingly, in his seminal study on cultural differences in self-perception, Cousins (1989) found that Japanese used more “universal-oceanic” statements when describing themselves than did Americans (e.g., “I am a human being”). His coding category is a similar (but narrower) classification scheme that we believe is related to dialecticism, and more specifically, to the theory of holism. Cousins offered little in the way of an explanation for his finding, stating only that it helped rule out “an incomplete advance in social cognition” among Japanese (p. 128). However, these self-statements are consistent with the contention that members of dialectical cultures conceive of themselves in holistic terms.

Importantly, the results reported here are not simply due to differences in the grammatical structure of the Mandarin and English languages. Although there are variations in how aspect (the duration of an action), tense (when an action occurred), negation, modification, and so on, are expressed in these languages, Mandarin is not inherently more dynamic, contradictory, or holistic than is English, and language differences did not constrain participants' responses (C. N. Li, personal communication, March 12, 2005; Li & Thompson, 1981; Xiao & McEnery, 2004). Moreover, our central findings remained significant when controlling for self-criticism.

STUDY 2

In Study 2, we examined a second cognitive mechanism that gives rise to contradictory global self-judgments. Specifically, we tested whether members of a dialectical culture (in this case, Japanese) exhibit greater simultaneous accessibility of contradictory self-knowledge than do Euro-Americans. In the attitudinal ambivalence literature, simultaneous accessibility is assessed by measuring participants' latencies in responding to unipolar, evaluative statements (Newby-Clark, McGregor, & Zanna, 2002). These methods have been used to index the accessibility of conflicting attitudes or “how quickly and equally quickly conflicting evaluations come to mind” (p. 157), such as pro- and anti-sentiments toward abortion. We adapted this methodology to assess the simultaneous accessibility of contradictory self-knowledge. Participants made me versus not me judgments on various contradictory traits presented on the computer, and accessibility (speed) scores were computed. As contradictory self-beliefs are brought to mind more quickly, and equally quickly, the accessibility scores increase. We predicted that Japanese would exhibit significantly greater simultaneous accessibility than would Euro-Americans.

In this study, we also examined whether cultural differences in global self-concept inconsistency would be obtained with a timed, computer task. Self-presentation concerns represent an alternative explanation for our findings. In Western societies, people are motivated to provide internally consistent (Swann et al., 2003) and positive (Heine & Hamamura, 2007) responses to explicit questions about the self. Therefore, we examined whether Japanese participants would exhibit greater self-concept inconsistency on a less obtrusive measure than would Euro-Americans: By eliciting rapid self-judgments, participants are less likely to control or edit their responses and hence are less likely to present a self-image that is culturally normative or pleasing to the experimenter or to themselves. We compared participants' responses on a timed computer task versus a traditional paper-and-pencil measure, and we tested whether the effects would hold when controlling for an index of self-criticism.

As outlined in the Introduction, it is possible that East Asians demonstrate greater self-concept inconsistency because they are less certain of who they are (Campbell et al., 1996). To test this alternative explanation, we repeated our analyses controlling for self-concept certainty (indexed by participants' response latency on the trait ratings; Baumgardner, 1990; Campbell, 1990; Markus, 1977). First, inconsistency scores were used to index the internal consistency of participants' self-judgments (Thompson, Zanna, & Griffin, 1995). Specifically, contradictory self-beliefs were assessed with separate, unipolar scales (e.g., “How extraverted are you?” vs. “How introverted are you?”). A formula was then applied to the responses and a single inconsistency index was obtained. These scores measure how strongly, and equally strongly, participants rate themselves on various contradictory attributes. We predicted that Japanese participants would exhibit greater inconsistency in their self-judgments than would Euro-Americans, and that cultural differences in self-concept inconsistency would hold even when controlling for self-concept certainty (response latency).

Method

Participants and Procedure

Participants were 58 Japanese students (24 women, Mage = 23.7) at the Shibaura Institute of Technology and University of Tokyo, and 35 Euro-Americans (21 women, Mage = 19.0) at UC Berkeley. Participants were tested in groups of 1 to 4 in the United States and individually in Japan.3 Participants completed several practice trials, the computer task, and the questionnaire measure.

Measures

Computer task

Participants made self-judgments about contradictory traits related to extraversion and creativity, domains that are of general importance to both cultures (Heine et al., 2001; McCrae, Zonderman, Costa, & Bond, 1996). Participants were asked to indicate as quickly as possible the self-descriptiveness of various traits by pressing either a me or a not me key on the keyboard (using Inquisit software; Millisecond Software, 2002). The traits consisted of extraverted–introverted words (e.g., outgoing–shy), creative– conventional words (e.g., imaginative–conventional), and filler (noncontradictory) words (e.g., gentle, honest). The words were presented randomly in two blocks of 40 words each, and the keys corresponding to me and not me were counterbalanced across blocks. Both participants' self-judgments (1 = me, 0 = not me) and response latencies were recorded.

Questionnaire task

To compare our findings across response formats, participants also completed a questionnaire in which they indicated how often 34 traits were characteristic of them using a 1 (not often at all) to 7 (very often) scale.4 The traits consisted of extraverted– introverted, creative–conventional, and filler (noncontradictory) words that were similar but not identical to those in the computer task.

Results

Across studies, there were no main effects or interactions involving gender. Thus, gender is not discussed further.

Participant Selection

Because there is no research participant pool at the Japanese universities, we were unable to prescreen and recruit Japanese and Euro-American participants that were matched on the trait domains. Nevertheless, to control for the possibility that cultural differences on the dependent variables could be due to group-level differences in extraversion or creativity (e.g., Euro-Americans being more extraverted than Japanese), we matched the samples on the trait domains. We did so by oversampling and then dropping the least extraverted participants (one by one) until there were no mean differences between the cultural groups on the computer task, F < 1. The same steps were taken to match the samples on creativity, F < 1. For the sake of simplicity, all analyses are reported with these matched samples. However, the results were the same with the unmatched samples, ps < .05.

Simultaneous Accessibility

Following standard procedures (Greenwald, McGhee, & Schwartz, 1998), any response under 300 or over 3000 ms was converted to 300/3000 ms, respectively. A reciprocal transformation was used to normalize the latencies, such that response latencies became speed scores.

Following procedures outlined in Newby-Clark et al. (2002), accessibility scores were computed. First, we computed the mean speed scores for extraverted me and introverted me judgments. These two variables were then used to create an accessibility score for extraversion/introversion (E/I) according to the negative acceleration model (NAM; Scott, 1966). Specifically, we applied the formula: (2 × S + 1)/(S + L + 2), where S is the smaller value (speed score) and L is the larger value (speed score).5 The same steps were taken to compute a creativity/conventionality (C/C) accessibility score. Higher scores correspond to greater accessibility. As predicted, Japanese exhibited greater simultaneous accessibility of contradictory self-knowledge than did Euro-Americans in both domains (see Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Mean Simultaneous Accessibility and Self-Concept Inconsistency Scores by Culture and Domain

| Japan | U.S. | df | F | p < | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extraversion/introversion | |||||

| Simultaneous accessibility | 0.70 | 0.67 | 53 | 4.96 | .05 |

| Self-concept inconsistency (computer) | 0.76 | 0.56 | 55 | 6.93 | .05 |

| Self-concept inconsistency (questionnaire) | 0.76 | 0.68 | 57 | 4.06 | .05 |

| Creativity/conventionality | |||||

| Simultaneous accessibility | 0.68 | 0.61 | 33 | 8.99 | .01 |

| Self-concept inconsistency (computer) | 0.50 | 0.28 | 54 | 5.50 | .05 |

| Self-concept inconsistency (questionnaire) | 0.76 | 0.63 | 56 | 11.65 | .01 |

NOTE: The degrees of freedom are lower for the accessibility scores because of the response format. An accessibility score can only be computed for participants who responded “me” to at least one trait in each of the domains.

Self-Concept Inconsistency

The participants' self-judgments were used to compute inconsistency scores. From the computer task, four mean self-ratings (i.e., the proportions of me responses for extraversion, introversion, creativity, and conventionality) were computed. For Japanese Cronbach's alphas ranged from .77 to .81 (M = .80); for Euro-Americans they ranged from .55 to .81 (M = .73). A similar procedure was followed for the questionnaire task: For Japanese alphas ranged from .65 to .83 (M = .79); for Euro-Americans they ranged from .45 to .87 (M = .76).

We then calculated inconsistency scores for the E/I and C/C trait ratings and for the computer and questionnaire tasks, separately, according to the NAM method. For both tasks, the mean extraverted and introverted self-judgments were used as the S and L values. The same steps were taken to compute C/C inconsistency scores. These scores indicate how strongly, and equally strongly, participants rated themselves on the contradictory attributes. Higher scores correspond to greater self-concept inconsistency. As expected, Japanese exhibited greater self-concept inconsistency than did Euro-Americans for both tasks (see Table 3).

We controlled for self-criticism as follows: Because participants did not rate trait valence in this study, we consulted Anderson's (1968) likableness ratings, categorizing traits over 300 as positive and under 300 as negative. We occasionally used close synonyms (e.g., restrained is not listed in Anderson, 1968; therefore, we substituted inhibited; decisions were made using www.thesaurus.reference.com). For spontaneous accessibility, we controlled for the index: (mean reaction time for positive traits – mean reaction time for negative traits). The effect of culture remained significant for E/I, F(1, 55) = 4.50, p < .05, and C/C, F(1, 33) = 8.30, p < .01. For computer task self-concept inconsistency, we used: (number of negative traits endorsed – number of positive endorsed)/(number of negative traits endorsed + number of positive endorsed). The effect of culture remained significant for E/I, F(1, 55) = 5.22, p < .05, and C/C, F(1, 54) = 4.98, p < .05. For questionnaire task self-concept inconsistency, we used: (mean rating on negative traits – mean rating on positive traits). The effect of culture dropped to nonsignificance for E/I, F(1, 57) = 2.36, p = .13, and C/C, F < 1.

Self-Concept Certainty

Following previous researchers (Baumgardner, 1990; Campbell, 1990; Markus, 1977), self-concept certainty was indexed according to participants' response latencies, such that faster responses indicate greater certainty regarding one's self-beliefs. First, we examined whether Japanese and Euro-American participants differed in self-concept certainty. They took approximately the same amount of time to make the E/I judgments (MJapan = 1,086 ms, MUS = 1,159 ms), F(1, 55) = 1.20, ns, and C/C judgments (MJapan = 1,083 ms, MUS = 1,121 ms), F < 1, indicating that, on average, the Japanese participants were not less certain about their self-beliefs than were Euro-Americans.

Next, we investigated the relationship between self-concept certainty and self-concept inconsistency by examining the correlations between the certainty scores (speed of responding) and inconsistency scores for both trait domains. For E/I, this correlation was marginal and negative for Euro-Americans (r = −.32, p = .06), but nonsignificant for Japanese (r = .00, ns). For C/C, this relationship was negative for Euro-Americans (r = −.47, p < .01), but nonsignificant for Japanese (r = .04, ns). Hence, Euro-Americans who were more certain of their self-beliefs exhibited more self-concept consistency. Importantly, however, there was no association between self-concept certainty and self-concept inconsistency among Japanese. Finally, cultural differences in self-concept inconsistency remained when self-concept certainty was used as a covariate, for both E/I, F(1, 53) = 7.98, p < .01, and C/C, F(1, 52) = 7.01, p < .05.

Discussion

As predicted, Japanese participants exhibited significantly greater simultaneous accessibility of contradictory self-knowledge than did Euro-Americans in both personality domains. These findings suggest that contradictory self-knowledge is more accessible or retrieved more efficiently from memory among members of dialectical than synthesis-oriented cultures. Our hypothesis that Japanese would demonstrate greater self-concept inconsistency on the computer task was also supported, and the results were not due to a lack of self-concept certainty among Japanese. Japanese and Euro-Americans did not differ with respect to the average speed with which they processed the traits, suggesting Japanese were not less certain about their self-beliefs in general. Moreover, self-concept certainty was not significantly related to self-concept inconsistency among Japanese, and our cultural differences remained significant when controlling for this index.

In this study, cultural differences in global self-concept inconsistency were found using a less obtrusive measure, suggesting our effects are not simply due to cultural differences in self-presentation, in which Euro-Americans strive to provide internally consistent responses to overt questions about the self. Japanese exhibited greater self-concept inconsistency even when they responded very quickly (on average, in about 1 s) and thus presumably could not have easily monitored their responses or engaged in other types of effortful self-presentation. Notably, when we controlled for self-criticism, or the tendency to endorse negative self-descriptions, the cultural differences remained significant on the computer task but not on the paper-and-pencil task. This is not surprising given that the paper-and-pencil task is an untimed, explicit (conscious) measure that is more susceptible to social desirability and self-presentation concerns. Of course, these results do not rule out self-presentation concerns as an alternative explanation for our findings. Therefore, we conducted a study that examined contradiction in people's implicit self-beliefs.

STUDY 3

In Study 3, we investigated whether members of a dialectical culture (Chinese) would exhibit greater contradiction in their implicit self-beliefs. One might argue that our previous findings are due to cultural differences in how East Asians and Euro-Americans talk about or express the self rather than to deeper, underlying differences in global self-knowledge. Likewise, the findings could be due to cultural differences in scale usage. In Study 2 and previous research (Choi & Choi, 2002), participants were prompted to judge their standing on various attributes. Perhaps East Asians simply agree with stimulus items without regard to content and this acquiescence is manifested as greater self-concept inconsistency. Alternatively, East Asians may obtain higher self-concept inconsistency scores because they prefer moderate responses.

One way to demonstrate that the self-concept inconsistency of East Asians is not due to self-report biases is to show that it exists at an implicit level. Implicit measures reflect the growing appreciation that people process social information in a relatively automatic manner (Greenwald et al., 1998). Research examining the relationship between culture and implicit belief systems has been largely restricted to the domain of implicit self-evaluation (e.g., Kitayama & Karasawa, 1997). For example, Kitayama and Karasawa (1997) found that Japanese prefer their own name syllables to others in the Japanese syllabary, suggesting they evaluate themselves positively at an implicit level.

In this study, we used a different implicit measure: an open-ended, surprise recall task. Chinese and Euro-American participants were presented with a list of contradictory and filler (noncontradictory) words, and they generated an autobiographical memory (ABM) for each word. Following a distracter task, they were asked to recall as many of the words and associated ABMs as possible. This recall task is an implicit measure of self-beliefs for several reasons. First, previous research has shown that people remember self-relevant information more easily than other types of information (Rogers, Kuiper, & Kirker, 1977); hence, the stimulus words and ABMs recalled were likely to be highly self-relevant. Second, participants were not consciously aware of the self-relevance of the task, and even if they were, they could not control what words they actually remembered (Bargh, 1994). We predicted that Chinese participants would remember a greater proportion of contradictory versus filler words, compared to Euro-Americans.

Method

Participants

Forty-seven Chinese students at Peking University (22 women, Mage = 20.2) participated for 15 yuan (∼$2), and 42 Euro-American students (22 women, Mage = 19.8) at UC Berkeley participated for course credit. Participants completed the study in small groups. Using Inquisit (Millisecond Software, 2002), they completed a self-rating task and an ABM task. They then completed a paper-and-pencil free recall task, several measures unrelated to this study, and a probe for suspicion.

Procedure

Trait selection

Approximately 80 words were randomly sampled from each of the Big Five factors (McCrae et al., 1996). Opposites were generated for half of the words. All trait terms were then translated into Mandarin and back-translated into English. The bilingual research team subsequently selected 14 pairs of contradictory words (28 traits) that were clearly contradictory and 32 filler words that were noncontradictory in both languages. Sample contradictory words include: intelligent–foolish, hardworking–lazy, reliable–undependable, enthusiastic–restrained, active–passive, and talkative–quiet. Sample filler words include: romantic, wasteful.6

ABMs

Participants generated an ABM for each of the 60 words. Specifically, they were instructed to “remember a specific experience in your life in which you were [word].” After completing three practice trials, the contradictory and filler words were presented in random order. Participants were asked to generate an ABM as quickly as possible and then to press the 5 key. If a participant did not respond within 60 s, the trial timed out and the next word appeared.

Following a 5-min distracter task, participants were unexpectedly asked to recall as many of the 60 words as they could and to describe the associated memories in three to five lines. They were given 15 min to complete this task. In most cases (86%), participants listed both a stimulus word and an associated memory, but in some cases, participants only described the memory. Therefore, to label the memories, participants coded their responses using a numbered list with all 60 words. Two research assistants later verified the coding accuracy.

Results

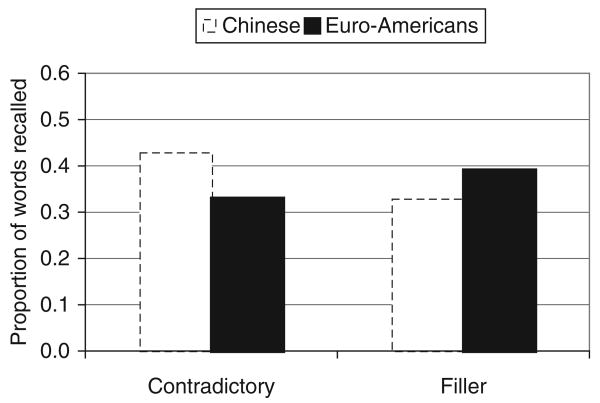

Do Chinese exhibit greater self-concept inconsistency than do Euro-Americans on an implicit measure? We first computed the proportions of contradictory and filler words (see Figure 1). Both words from a contradictory pair had to be remembered to be counted. We then conducted a Culture (between: Chinese vs. Euro-American) × Type of Word (within: contradictory vs. filler) ANOVA, which revealed only the expected Culture × Type interaction, F(1, 84) = 6.91, p < .05.

Figure 1.

Study 3: Mean proportion of words recalled, by type of word and culture.

To decompose this interaction, separate ANOVAs for the contradictory and filler word proportions were conducted. As expected, Chinese participants remembered a greater proportion of contradictory words than did Euro-Americans, F(1, 85) = 6.15, p < .05. Euro-Americans remembered more filler words than did Chinese, F(1, 85) = 4.58, p < .05. We also examined the tendency to remember contradictory versus filler words for each culture separately. Euro-Americans were as likely to remember contradictory as filler words. In contrast, Chinese were more likely to remember contradictory than filler words, F(1, 43) = 5.93, p < .05.7

Discussion

Using a surprise recall task, we found that members of a dialectical culture (Chinese) recalled significantly more contradictory versus filler (noncontradictory) words and ABMs relative to Euro-Americans. Chinese participants recalled more contradictory self-relevant information, suggesting again that a greater amount of inconsistent self-knowledge is accessible among East Asians relative to Euro-Americans. Moreover, this task was unobtrusive and less susceptible to self-presentation concerns. Participants were not required to rate or describe various aspects of the self. Rather, they were only asked to recall a list of words and their associated memories. None of the participants indicated suspicion regarding the true purpose of the study or the contradictory nature of the stimuli. Because the free recall task represents an implicit measure of self-concept inconsistency, these results point to cultural differences in the underlying content and structure of the self-concept rather than simply to cultural variation in self-presentation style or socially normative means of expression.

STUDY 4

The purpose of Study 4 was to show directly that cultural differences in global self-concept inconsistency are not simply due to the greater tendency for East Asians to endorse negative statements as being true of the self (Heine & Hamamura, 2007). As noted in the Introduction, the tendencies to endorse semantic opposites and traits of opposite valence are potentially confounded. To address this, Chinese, Chinese American, and Euro-American participants indicated whether words related to extraversion and introversion were true of themselves and, after a series of intervening tasks, rated the valence of the attributes. This ideographic design is thus an improvement over Study 1, in which judges rated the valence of participants' self-statements. We expected that cultural differences in self-concept inconsistency would hold even when controlling for self-criticism.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Seventy-one Chinese students at Peking University (42 women, Mage = 20.9) participated for 8 yuan (∼$1), and 79 Chinese American (54 women, Mage = 19.7) and 76 Euro-American (47 women, Mage = 20.2) students at UC Berkeley participated for course credit.

Participants were tested in small groups. Upon arriving at the lab, they were greeted by an experimenter and seated at a table with a computer. Using Inquisit (Millisecond Software, 2002), participants completed the attribute ratings, several measures unrelated to this study, and the valence ratings. Participants were permitted to take as much time as they needed to make the ratings. Finally, they completed a paper-and-pencil demographics questionnaire, a suspicion probe, and were debriefed.

Measures

Attribute ratings

Participants rated the extent to which 28 attributes were characteristic of them on a 1 (not at all) to 9 (very much) scale. Of the attributes, 4 were related to extraversion (i.e., extraverted, outgoing, talkative, active) and 4 to introversion (i.e., introverted, quiet, withdrawn, shy). The stimulus words were separated by several filler words (e.g., athletic, funny, hardworking).

Valence ratings

Participants rated the valence of the attributes on a 1 (very negative) to 9 (very positive) scale.

Results and Discussion

Participant Selection

As in Study 2, to control for the possibility that cultural differences on the dependent variable could be due to group-level differences in extraversion (e.g., Euro-Americans being more extraverted than Chinese), we matched the samples by oversampling and then dropping the least extraverted participants (one by one) until there were no mean differences among the cultural groups, F < 1. All analyses are reported with these matched samples, although the results were the same with the unmatched samples, ps < .05.

Self-Concept Inconsistency

The responses for the extraverted and introverted attributes were averaged. Cronbach's alphas were as follows: Euro-Americans, extraverted = .87, introverted = .86; Chinese Americans, extraverted = .87, introverted = .83; Chinese, extraverted = .78, introverted = .69. The mean extraversion and introversion ratings were then used to create an index of self-concept inconsistency using the NAM formula (see Study 2).

An ANOVA revealed a main effect of culture, F(2, 199) = 5.97, p < .01. As expected, both Chinese (M = .77) and Chinese Americans (M = .75) demonstrated greater self-concept inconsistency than did Euro-Americans (M = .69), ps < .05. The former groups did not differ from each other.

Self-Criticism

To create an index of self-criticism, we subtracted participants' mean scores on the negative traits from their mean scores on the positive traits, such that higher values indicate greater self-criticism. There were no cultural differences on this measure (Ms = 2.97, 2.90, and 2.81 for Euro-American, Chinese American, and Chinese participants, respectively), F < 1. Importantly, when the self-concept inconsistency analysis was repeated with the self-criticism index as a covariate, the cultural differences remained significant, F(2, 201) = 5.12, p < .01. These findings bolster our assertion that cultural differences in self-concept inconsistency are not simply to due to the negativity of one's self-concept judgments.

STUDY 5

The results of Studies 1 to 4 indicate that a greater amount of contradictory self-knowledge is available and accessible among members of dialectical cultures than among nondialectical cultures. The purpose of Study 5 was to replicate and extend these findings by testing the direct relationship between dialecticism and global self-concept inconsistency. The DSS (Spencer-Rodgers et al., 2008), an individual difference measure of naïve dialecticism, was completed by members of three cultures known to be highly dialectical (Chinese), moderately dialectical (Asian Americans), and nondialectical (Euro-Americans). We anticipated that dialecticism would mediate cultural differences in self-concept inconsistency.

Method

Participants and Procedure

One hundred and fifty-seven Chinese students (97 women, Mage = 22.3) at Peking University participated for 10 yuan (∼$1), and 78 Asian American (54 women, Mage = 19.6) and 53 Euro-American students (31 women, Mage = 19.5) at UC Berkeley participated for course credit.

Participants were brought into the lab in small groups. They were told that the researchers were developing several new personality tests. Participants completed the first “personality test,” which consisted of the DSS and several unrelated measures. They then completed a second “personality test,” which consisted of 49 attribute ratings; a demographics questionnaire; and were debriefed.

Measures

Dialecticism

Dialecticism was assessed with the DSS, with the 32 items rated on a 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) scale. Sample items include: “When I hear two sides of an argument, I often agree with both”; “I sometimes believe two things that contradict each other”; and “I often find that my beliefs and attitudes will change under different contexts.” Cronbach's alphas were .84 for Euro-Americans, .81 for Asian Americans, and .74 for Chinese.

Prior research indicates that the DSS has adequate psychometric properties. Cronbach's alphas have been examined among various cultural groups and fall in the .69 to .87 range. With respect to test–retest reliability, over a 4-week interval, alphas have ranged from .70 to .91. The scale also shows adequate convergent/discriminant validity (e.g., the DSS is negatively correlated with need for cognitive closure; Kruglanski, Webster, & Klem, 1993) and predictive validity (e.g., scores on the DSS predict dialectical self-esteem; Spencer-Rodgers et al., 2004). The DSS has a three-factor structure and the subscales include contradiction, cognitive change, and behavioral change. The scale was designed to be a “global” measure of dialecticism, and all three subscales are related to self-concept inconsistency. Therefore, we used an overall DSS score in our analyses.

Attribute ratings

Participants rated the extent to which 49 contradictory and filler (noncontradictory) traits were typical of them on a 1 (not at all characteristic) to 9 (very characteristic) scale. The contradictory traits were embedded within the filler traits and consisted of 13 pairs, including: talkative–quiet, inventive–unimaginative, modern–traditional, logical–emotional, sociable–shy, realistic–idealistic, foolish–intelligent, determined–carefree, and organized–disorganized.

Results and Discussion

Dialecticism

An ANOVA revealed a main effect of culture, F(2, 285) = 9.54, p < .001. Both Chinese (M = 4.00) and Asian Americans (M = 3.90) scored higher on dialecticism than did Euro-Americans (M = 3.61), ps < .05. The former two groups did not differ from each other.

Self-Concept Inconsistency

Following the NAM model (see Study 2), inconsistency scores were computed using the 13 pairs of contradictory attributes. Of the demographic variables, there was a marginal association between age and the NAM scores (r = .11, p = .07) such that older participants exhibited greater self-concept inconsistency. All subsequent analyses were conducted controlling for age.

An ANOVA revealed a main effect of culture, F(2, 288) = 5.56, p < .01. Replicating the results of Study 2, both dialectical cultures, Chinese (M = .80) and Asian Americans (M = .80), exhibited greater self-concept inconsistency than did Euro-Americans (M = .76), ps < .05. The former two groups did not differ from each other.8

Does dialecticism mediate cultural differences in self-concept inconsistency? At Step 1, the NAM scores were regressed on culture (0 = Euro-American, 1 = Asian American, 2 = Chinese), and the association was significant (B = .19, p < .01). At Step 2, dialecticism was regressed on culture and again the relationship was significant (B = .35, p < .001). Finally, when we controlled for dialecticism, the relationship between culture and self-concept inconsistency dropped to nonsignificance (B = .09, ns; Sobel test: change in b = .10, p < .05). As predicted, the association between culture and self-concept inconsistency was fully mediated by dialecticism.

General Discussion

Culturally shared lay beliefs exert an important influence on Eastern and Western conceptual selves. Naïve dialecticism represents one constellation of folk theories about the nature of the world that shapes the self-concept. Focusing mainly on the theories of contradiction and change, we examined multiple aspects of the dialectical self using various methodologies. Across five studies, members of dialectical cultures (Chinese, Japanese, and Asian Americans) demonstrated greater global self-concept inconsistency than did Euro-Americans. Self-concept change and cognitive holism were also evident in the spontaneous self-concept.

A greater amount of contradictory self-knowledge appears to be available and accessible among East Asians relative to Euro-Americans. In Study 1, Chinese participants listed, without prompting, more contradictory paired self-statements and not-self-statements on the TST. The stimulus question “Who am I?” activated a larger body of contradictory self-knowledge among Chinese than among Euro-Americans. In Study 2, Japanese participants exhibited significantly greater simultaneous accessibility of contradictory self-beliefs. In Study 3, Chinese participants recalled a greater amount of contradictory self-knowledge than did Euro-Americans. Moreover, cultural differences in self-concept inconsistency were not due to self-criticism (Study 4) or self-concept certainty (Studies 2 and 3). Finally, in Study 5, dialecticism was shown to mediate cultural differences in self-concept inconsistency.

This research contributes to the existing literature on culture and the self, theoretically and empirically, in several ways. First, naïve dialecticism represents a relatively novel theoretical approach to understanding cultural differences in the self. Naïve dialecticism is a construct that is distinct from other cultural models (e.g., collectivism and interdependence) and is grounded in the lay theory rather than the value or self-construal traditions (Peng, Ames, & Knowles, 2001). The dialectical framework has great utility, both in terms of making novel cross-cultural predictions and in interpreting known findings. For example, whereas other cultural models (e.g., the interdependent-self perspective; Markus & Kitayama, 1991) view the self as interconnected with other people, naïve dialecticism conceptualizes the self as related to all other phenomena in the universe. Naïve dialecticism predicts that there will be greater interconnections between the self and all other material and spiritual objects. Cousins (1989) reported that East Asians use more transcendental statements such as “I am a human being” on the TST. These self-references fit appropriately within a dialectical framework (theory of holism) but are not well accounted for by other cultural models.

Second, the present studies extend earlier work on tolerance for contradiction (Choi & Choi, 2002; Peng & Nisbett, 1999) by going beyond explicit, closed-end, paper-and-pencil assessments. This research also provides direct evidence for the mediating effect of dialectical lay beliefs on self-concept inconsistency. Following the dynamic constructivist perspective (Hong & Mallorie, 2004), we contend that lay theories account for national or group-level differences in various psychological phenomena. These “naïve” beliefs are located in the minds of individuals but are cultivated by the broader society. In Study 5, we documented that Chinese are more likely than Euro-Americans to endorse such statements as “When I hear two sides of an argument, I often agree with both” (theory of contradiction) and “I sometimes find that I am a different person by the evening than I was in the morning” (theory of change). These beliefs, in turn, predicted self-concept inconsistency. Hence, this research explicates the mechanism through which dialectical folk theories give rise to national differences in self-conceptions. This research is also the first to show that East Asians (Japanese and Chinese) exhibit greater availability and simultaneous accessibility of contradictory self-knowledge, as well as greater internal inconsistency in their implicit self-beliefs than do Euro-Americans. Finally, we were able to discount numerous alternative explanations for our key findings, including cultural differences in self-criticism, self-concept certainty, self-presentation, scale usage, and response bias.

Nature and Structure of the Self-Concept

Do the present findings reflect surface-level or basic differences in the nature and structure of the self-concept? One might argue that East Asians and Euro-Americans vary only in self-presentation or in the manner in which they express or describe the self. As outlined in the Introduction, contradictory traits are almost always of opposite valence. Hence, the tendency to endorse contradictory attributes is naturally confounded with the tendency to endorse negative attributes. Consequently, it would be reasonable to expect that the East Asian proclivity to be more self-effacing (Heine & Hamamura, 2007) would give rise, at least in part, to cultural differences in self-concept inconsistency. Previous research on the dialectical self has failed to control for the East Asian proclivity toward self-effacement (e.g., Choi & Choi, 2002; Spencer-Rodgers et al., 2004). In all of the present studies, we repeated our self-concept inconsistency analyses controlling for an index of self-criticism. In almost all cases across all studies, our effects remained significant. Although the effects were eliminated on the questionnaire task in Study 2, they remained significant on the questionnaire tasks in Studies 1 and 4 and when the measure was timed or implicit (spontaneous accessibility and computer task in Study 2, autobiographical task in Study 3). Thus, cross-cultural differences in self-concept inconsistency exist beyond what can be attributed to self-criticism.

Our research points to significant cultural differences in the encoding, representation, retrieval, and processing of contradictory self-relevant information. The representation of contradictory self-knowledge appears to differ for members of dialectical and synthesis-oriented cultures. Because members of dialectical cultures embrace dual aspects of the self (yin–yang) and conceptualize the self as constantly changing, the content of their global self-concept, including their working self-concept, will be more contradictory and variable. The findings from Study 1 suggest that their behavioral stores include more remembered instances of contradictory behaviors, such as extraversion and introversion, creativity and conventionality, and so on. In addition to greater availability, the results of Study 2 indicate that inconsistent self-knowledge is more readily accessible among Japanese than among Euro-Americans.

The structure of the self-concept may also differ for members of dialectical and synthesis-oriented cultures. If self-knowledge is stored in memory as associative networks of self-relevant beliefs (Kihlstrom, Beer, & Klein, 2003), the associative networks of members of dialectical cultures may differ substantially from those of synthesis-oriented cultures. Self-knowledge, like other kinds of knowledge, is thought to be organized in memory as conceptual networks of nodes, with the self node associated with other nodes representing semantic and episodic knowledge (Kihlstrom et al., 2003). Previous research indicates that counterschematic, episodic memories are primed by the retrieval of schematic self-knowledge. When individuals are asked to make trait summary judgments, they are significantly faster at recalling incidents in which they behaved in a contradictory, counterschematic manner (Klein, Cosmides, Tooby, & Chance, 2001). For example, when asked, “Does the word outgoing describe you?” they are faster at recalling a time when they were shy. It is possible that inconsistent information is stored more closely together in the conceptual networks of members of dialectical cultures. If so, thinking of a particular self-belief may more readily activate a contradictory self-belief. Further research is needed to determine the extent to which self-knowledge is encoded, organized, stored, and processed differently among members of dialectical and synthesis-oriented cultures.

Unresolved Questions

Several interesting questions remain, and in this section we consider two related issues: The first concerns the relationship between global and role-based self-views, and the second involves implications for psychological functioning.

First, the present research examined the internal consistency of one's global self-beliefs rather than context-specific self-beliefs. Although not tested in this research, it is perfectly plausible that East Asians show greater contradiction in their global self-judgments but equal (or even less) contradiction in their situation- or role-specific self-judgments than Euro-Americans (see English & Chen, 2007). An interesting direction for future research would be to examine the association between abstract or global self-beliefs and more specific, role-based self-conceptions. The current article focused on abstract self-beliefs, but people can define themselves differently in different roles or contexts (e.g., self-at-school, self-with-boss). Moreover, there are individual differences in cross-role variation in self-knowledge, or the extent to which people define themselves differently depending on the role or context (e.g., Sheldon, Ryan, Rawsthorne, & Ilardi, 1997). We believe a cultural lens may shed light on this issue. For members of synthesis-oriented cultures, self-consistency and self-coherence are culturally mandated. Consequently, there may be a relatively “adversarial” relationship between global and role-based self-views. When specific, role-based self-aspects are at odds with one's global self-views, the former may be conceptualized as inauthentic parts of the self, or as self-aspects that only emerge when the situation constrains one's “true self” (Sheldon et al., 1997). Hence Euro-Americans might recognize multiple self-aspects (e.g., “I am loud with friends and quiet with professors”) but believe that the situational press (e.g., being with their professors) constrains their true nature. On the other hand, for members of dialectical cultures, the self is perceived as interconnected (theory of holism), and the ability to change and tolerate contradiction is culturally mandated. Thus, role-based self-aspects may be more easily incorporated into one's global self-views, even when conceptually contradictory. We are currently investigating these questions in our laboratory.9

A related question concerns the implications self-concept inconsistency has for psychological health and functioning. Previous research has found that cross-role consistency is a stronger predictor of subjective well-being in the United States than in Korea (Suh, 2002). We are currently exploring the link between inconsistency and interpersonal flexibility, that is, the perception of having a wide variety of situation-specific behavioral responses (Paulhus & Martin, 1988). Because members of dialectical cultures are greatly attuned to the situation and the kinds of behavior that are appropriate in different situations, they are much more comfortable with flexibly changing their behavior to fit the situation. This ability is highly agentic and adaptive in this cultural context. Moreover, because East Asians tolerate contradiction, they more comfortably acknowledge that flexible responding is part of their authentic personality. Among members of dialectical cultures, one should find a high degree of cross-role variation and greater incorporation of different roles into one's global self-concept. Instead of leading to adverse psychological consequences (Campbell, 1990), self-concept inconsistency could be adaptive in dialectical cultural contexts, reflected in higher self-esteem, subjective well-being, and so on. For members of synthesis-oriented cultures, cross-role variation may instead be associated with situationality, or the idea that one's personality is dependent on the situation. Indeed, in the United States, self-conceptions reflecting interpersonal flexibility are associated with higher self-esteem, whereas those reflecting situationality are associated with poorer functioning (Paulhus & Martin, 1988). We are currently exploring the links among culture, cross-role variation, self-concept inconsistency, interpersonal flexibility, and psychological well-being.

Concluding Remarks

As with self-enhancement, self-coherence is regarded as a fundamental human motive in Western psychology (e.g., Festinger, 1957). According to self-verification theory (Swann et al., 2003), people strive for internal consistency and temporal stability in their thoughts, feelings, and actions. These qualities of the self are viewed as normative and desirable in synthesis-oriented cultures and are generally associated with psychological well-being in the West (Campbell, 1990; Suh, 2002). Coherent self-views provide people with an important means of organizing experience, defining one's existence, guiding social behavior, and predicting future outcomes.

Is self-coherence an equally potent human motive in all cultures? Our research raises an interesting possibility: The search for self-coherence may indeed be a fundamental human motive, but “coherence” may be achieved in a strikingly different manner among East Asians. In the West, individuals strive for internal consistency, such that if a person possesses a large amount of quality A (e.g., extraversion), then he necessarily possesses very little of the opposing quality not-A (e.g., introversion). In dialectical cultures, individuals may strive for equilibrium, such that if a person possesses a large amount of quality A, to balance the scale, she necessarily possesses a substantial amount of the opposing characteristic (see Kitayama & Markus, 1999). Equilibrium may serve the same function for East Asians as internal consistency does for Westerners by providing individuals with a means of organizing experience, understanding themselves, guiding social behavior, predicting future outcomes, and so on. East Asians may also exhibit an equal or even greater degree of internal consistency, relative to Americans, in their beliefs and attitudes in other psychological domains, such as those related to the interdependent self or attitudes toward social outgroups (Hoshino-Browne et al., 2005; Kitayama et al., 2004; Spencer-Rodgers, Williams, Hamilton, Peng, & Wang, 2007). Naïve dialecticism provides a comprehensive, theoretical framework for understanding these cultural differences, and the contradictory, changeable, and holistic nature of the East Asian self-concept.

Acknowledgments

We thank Serena Chen, Melissa Williams, Sara Gorchoff, and Lindsay Shaw Taylor for their invaluable comments. This research was supported by National Institute of Mental Health Grant MH72680 (to Kaiping Peng and Julie Spencer-Rodgers) and a University of California, Berkeley Institute of East Asian Studies fellowship (to Helen Boucher). We thank Antonio Cortijo, Jiangqun Liao, Lu Gan, Nicky Newton, Emily Li, Alice Lin, Min Yu, Xiao He, Yueyi Huang, Sarah Ford, and Sandy Tsang for their assistance.

Footnotes

Approximately one third of the raw Twenty Statements Test data from Spencer-Rodgers, Peng, Wang, & Hou (Study 2; 2004) was coded and analyzed for an entirely different purpose (according to the Dialectical Coding Scheme) and included in this study. Gender information was not collected in China.

Contrary to prediction, the proportions of temporally/situationally modified self-statements were not greater for Chinese. This is surprising given that East Asians tend to describe themselves in terms of activities and concrete behaviors (“I am someone who likes to play volleyball on Fridays”; Cousins, 1989; Kanagawa, Cross, & Markus, 2001), and Mandarin relies on adverbs (e.g., yesterday) to express tense (Xiao & McEnery, 2004). On the other hand, we examined the extent to which Chinese modified all of their self-statements. Perhaps only certain attribute types (e.g., activities/behaviors) are temporally/situationally modified more among East Asians.

To examine whether this influenced the results, we compared Japanese responses with those of Euro-Americans tested alone versus in groups. Because results were the same, we retained all Euro-Americans.

Participants drew ranges (circles) on the 7-point scale. The original purpose was to examine whether Japanese rate their characteristics as more variable. Because of a procedural error, this could not be examined. Instead, the mean response was recorded as the midpoint of the circled range.

Numerous formulas exist to index internally inconsistent beliefs. Although they differ mathematically, all measure a psychological state of tension or conflict. For example, rating oneself as 7 on outgoing and 7 on shy is highly contradictory, relative to rating oneself as 7 and 1 (or 1 and 7). Likewise, rating oneself with 7 on both intelligent and foolish is more contradictory than rating oneself with 3. Thus, the formulas take into account both the strength and similarity of responses. These scores are more sensitive indicators of inconsistency over a broad range of responses than other statistics, such as difference scores (Thompson et al., 1995). To provide convergent evidence, we used several indices (similarity-intensity model, positive acceleration model, and absolute value of the reaction time difference between the paired contradictory traits). For all indices, we obtained highly similar results; therefore, for the sake of simplicity we only report the negative acceleration model results.

Before the autobiographical memory task, participants indicated how certain they were of their standing on the 28 contrasting attributes on a 1 (not at all certain) to 9 (very certain) scale. We computed the mean self-concept certainty ratings for the specific attributes recalled by each participant. Euro-Americans (M = 7.01) and Chinese (M = 6.83) did not differ in certainty, F < 1. An ANCOVA was performed on self-concept inconsistency, controlling for certainty. The cultural differences remained significant, F(1, 77) = 11.84, p < .01.

Traits were categorized as positive or negative (see Study 2). An ANCOVA was performed using the following index of self-criticism: (number of negative traits recalled – number of positive traits recalled)/(number of negative traits recalled + number of positive traits recalled). The cultural differences remained significant, F(1, 85) = 9.55, p < .01.

An ANCOVA was performed using the following index of self-criticism: (mean on negative traits – mean on positive traits). The cultural differences remained significant, F(2, 287) = 4.18, p < .05.

Given this discussion of role- versus situation-based self-views, one could ask about the relationship between dialectical self-views and self-monitoring (Snyder, 1974), which includes both attentiveness to cues regarding appropriate behavior in a given situation and the ability to adjust one's behavior accordingly. Conceptually, dialectical self-views and self-monitoring are similar, and future research should examine their relationship.

Contributor Information

Julie Spencer-Rodgers, University of California, Santa Barbara.

Helen C. Boucher, Bates College

Sumi C. Mori, University of Tokyo

Lei Wang, Peking University.

Kaiping Peng, University of California, Berkeley.

References

- Anderson NH. Likableness ratings of 555 personality-trait words. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1968;9:272–279. doi: 10.1037/h0025907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bargh JA. The four horsemen of automaticity: Awareness, intention, efficiency, and control in social cognition. In: Wyer RS, Srull TK, editors. Handbook of social cognition. 2nd. Vol. 1. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1994. pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Baumgardner AH. To know oneself is to like oneself: Self-certainty and self-affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1990;58:1062–1072. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.58.6.1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JD. Self-esteem and clarity of the self-concept. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1990;59:538–549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JD, Trapnell PD, Heine SJ, Katz IM, Lavallee LF, Lehman DR. Self-concept clarity: Measurement, personality correlates, and cultural boundaries. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;70:141–156. [Google Scholar]

- Choi I, Choi Y. Culture and self-concept flexibility. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2002;28:1508–1517. [Google Scholar]

- Cousins SD. Culture and self-perception in Japan and the United States. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1989;56:124–131. [Google Scholar]

- English T, Chen S. Culture and self-concept stability: Consistency across and within contexts among Asian Americans and European Americans. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2007;93:478–490. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.93.3.478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Festinger L. A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald AG, McGhee D, Schwartz J. Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition: The Implicit Association Test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;74:1464–1480. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.6.1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampson SE. When is an inconsistency not an inconsistency? Trait reconciliation in personality description and impression formation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;74:102–117. [Google Scholar]

- Heider F. The psychology of interpersonal relations. New York: John Wiley; 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Heine SJ, Hamamura T. In search of East Asian self-enhancement. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2007;11:4–27. doi: 10.1177/1088868306294587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heine SJ, Kitayama S, Lehman DR, Takata T, Ide E, Leung C, et al. Divergent consequences of success and failure in Japan and North America: An investigation of self-improving motivations and malleable selves. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2001;81:599–615. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heine SJ, Lehman DR. Culture, dissonance, and self-affirmation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1997;23:389–400. [Google Scholar]

- Heine SJ, Lehman DR. Culture, self-discrepancies, and self-satisfaction. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1999;25:915–925. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ET. Knowledge activation: Accessibility, applicability and salience. In: Higgins ET, Kruglanski AE, editors. Social psychology: Handbook of basic principles. New York: Guilford; 1996. pp. 133–168. [Google Scholar]

- Hong YY, Mallorie L. A dynamic constructivist approach to culture: Lessons learned from personality psychology. Journal of Research in Personality. 2004;38:59–67. [Google Scholar]

- Hoshino-Browne E, Zanna AS, Spencer SJ, Zanna MP, Kitayama S, Lackenbauer S. On the cultural guises of cognitive dissonance: The case of Easterners and Westerners. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005;89:294–310. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.89.3.294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanagawa C, Cross SE, Markus HR. “Who am I?” The cultural psychology of the conceptual self. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2001;27:90–103. [Google Scholar]

- Kihlstrom JK, Beer J, Klein SB. Self and identity as memory. In: Leary M, Tangney J, editors. Handbook of self and identity. New York: Guilford; 2003. pp. 68–90. [Google Scholar]

- Kitayama S, Karasawa M. Implicit self-esteem in Japan: Name letters and birthday numbers. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1997;23:736–742. [Google Scholar]

- Kitayama S, Markus HR. The yin and yang of the Japanese self: The cultural psychology of personality coherence. In: Cervone D, Shoda Y, editors. The coherence of personality: Social cognitive bases of personality consistency, variability, and organization. New York: Guilford; 1999. pp. 242–302. [Google Scholar]

- Kitayama S, Snibbe AC, Markus H, Suzuki T. Is there any “free” choice? Self and dissonance in two cultures. Psychological Science. 2004;15:527–533. doi: 10.1111/j.0956-7976.2004.00714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein SB, Cosmides L, Tooby J, Chance S. Priming exceptions: A test of the scope hypothesis in naturalistic trait judgments. Social Cognition. 2001;19:443–468. [Google Scholar]

- Kruglanski AW, Webster DM, Klem A. Motivated resistance and openness to persuasion in the presence or absence of prior information. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1993;65:861–876. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.65.5.861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn M, McPartland T. An empirical investigation of self-attitudes. American Sociological Review. 1954;19:68–76. [Google Scholar]

- Lausberg H. Handbook of literary rhetoric: A foundation for literary study. Boston: Brill; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Lewin K. Field theory in social science. New York: Harper; 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Li CN, Thompson S. Mandarin Chinese: A functional reference grammar. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1981. [Google Scholar]