It has been 30 years since landmark studies by Johnson and Brody revealed a pivotal role for the forebrain circumventricular organs (CVOs) in experimental hypertension1. We have since come to understand that these small midline structures, mounted along the cerebral ventricles and lacking well formed blood-brain-barriers, shoulder a huge responsibility for maintaining the delicate balance of cardiovascular and body fluid homeostasis. With their exotic cytology and morphology, including ‘neuron-like’ cells lying free on the ependymal surface and unusually dense and complex fenestrated capillary networks, the CVOs are involved in a remarkable array of homeostatic functions ranging from thirst and salt appetite to vasopressin release and sympathetic outflow2. With the study by Lob et al. in this issue of Hypertension3, we must also consider adding to this list the key role CVOs play in linking central and peripheral mechanisms of hypertension through activation of peripheral T lymphocytes. If proven true, these findings could have broad implications for a unifying hypothesis of how the CNS, the vasculature and possibly other peripheral organs, including the kidney, are involved in the etiology of hypertension.

The first of two major findings in the study by Lob et al. supports and extends previous reports that reactive oxygen species signaling in the subfornical organ (SFO) – a key forebrain CVO – is critical in angiotensin II (Ang-II)-mediated regulation of blood pressure and hypertension4,5. Using an established viral gene transfer approach that induces robust transgene expression nearly exclusively in the SFO6, Lob and colleagues show that SFO-targeted ablation of endogenous extracellular superoxide dismutase (SOD3), one of three isozymes in mammals that catalyzes dismutation of superoxide (O2•−), causes a significant elevation in basal blood pressure. In addition, deletion of SOD3 in the SFO increases the sensitivity to systemic Ang-II at a dose that does not normally affect blood pressure in mice. These studies using gene deletion lead to a similar general conclusion as was made earlier using gene overexpression, namely that elevated levels of O2•− in the SFO leads to hypertension. What is new and important here is the unmasking of a key role for the extracellular form of SOD. In previous studies, we showed that adenoviral-mediated overexpression of cytoplasmic Cu/Zn SOD (SOD1) or mitochondrial SOD (SOD2) but not SOD3 in the SFO interfered with the pressor effects of Ang-II4,5. However, as shown earlier and reiterated in the study by Lob et al., SOD3 is expressed at high basal levels in SFO. This may explain why further overexpression of this form of the enzyme failed to inhibit the pressor effects of Ang-II in our earlier studies. The use of Cre-loxP technology and selective deletion of endogenous SOD3 in the present study elegantly reveals that extracellular O2•− signaling in SFO is also important. Future analysis of the relative expression, distribution and functional role of these three SOD isozymes in SFO will be important in understanding the mechanisms of central redox signaling and how it regulates hemodynamics.

The second and potentially groundbreaking finding in the study by Lob et al. is that the SFO, at least in part through SOD3, may couple central and peripheral oxidant systems through activation of peripheral T cells, thereby providing a possible common underlying mechanism of hypertension that spans multiple organ systems. These investigators show that SOD3 ablation in the SFO is sufficient to increase oxidants in both the SFO and the aorta, and this is accompanied by an elevation in sympathetic output and an increase in the number of circulating CD69+ T lymphocytes. Addition of low-dose Ang-II infusion does not have further effects on these endpoints in the SOD3-ablated mice. In contrast, it does enhance the number of inflammatory CD45+, CD3+ and CD69+ cells and expression of T cell recruitment molecules in peripheral aortic tissue. Broadly interpreted, these results suggest that elevating extracellular O2•− levels in the SFO through deletion of SOD3 causes significant alterations in peripheral T cell activation and vascular O2•− regulation and inflammation, leading to hypertension.

As with all potentially important discoveries, this study raises as many questions as it answers. The first and perhaps most important is the sequence of interplay - and therefore the exact cause-effect relationships - between the multiple signaling systems invoked, including O2•− in the SFO, sympathetic outflow, T cell activation, vascular O2•− regulation, vascular infiltration and blood pressure. Given the increase in basal sympathetic outflow with SOD3 deletion in SFO, and the known effect of oxidant stress to induce sympathoexcitation, it is highly plausible that this is a key initiating mechanism linking the central and peripheral responses observed in this study. Indeed, increased sympathetic activity could lead to each of the responses observed after SOD3 ablation, including T cell activation and aortic O2•− increases, in addition to direct actions on the vasculature and other peripheral organs. It will be critical to establish these causal links definitively and determine their relative roles. It will also be important to determine whether one or all of these responses, along with the elevated basal blood pressure, are necessary and/or sufficient for the effects observed after superimposition of Ang-II, including increased circulating CD4-/CD8- T cells, vascular infiltration and further augmentation of hypertension. Related to this is the question of whether Ang-II stimulates immune activation directly or through sympathetic nerve firing, or both, and to what relative extent these mechanisms are involved. Moreover, since the aorta is a conduction vessel and contributes little to vascular resistance, one wonders what an increase in T cells in the aorta means, and more importantly, whether Ang-II stimulates this response in resistance vessels. Finally, since the vascular inflammation and homing marker data were collected only at the end of the Ang-II infusion period when blood pressure was at its maximum, it is impossible with this experimental paradigm to tease out whether the inflammatory effects of Ang-II are the cause or the result of hypertension. However, if the studies are repeated at earlier time-points before maximum Ang-II-induced hypertension is reached, and it is revealed that inflammation plays a causative role in the severe hypertension of this model, it will be important to determine the mechanism by which this occurs. Although there is no further augmentation of vascular O2•− with Ang-II treatment in this study, increased oxidative stress is a likely culprit and should be examined in other target end-organs, particularly the kidney.

Another important series of questions raised by the Lob et al. study concerns the local cellular mechanisms at play with SOD3 ablation and extracellular O2•− formation in the SFO, particularly as it relates to Ang-II-mediated intracellular signaling mechanisms. Certainly more work will be required to fully address this, but previous studies may provide a few clues. For example, increased scavenging of intracellular O2•− via overexpression of SOD1 significantly, but not completely, inhibits AngII-induced influx of extracellular Ca2+ 7. In contrast, inhibition of NADPH oxidase virtually abolishes this Ang-II response7–9, as well as the AngII-induced inhibition of K+ current10. We surmised that the differential effects of SOD1 overexpression and NADPH oxidase inhibition had to do with differences in efficiencies of increased O2•− scavenging versus suppression of O2•− production. However, given the study by Lob et al., it is tempting to speculate that a complete AngII-evoked response is dependent on both intracellular and extracellular O2•−. One could imagine that NADPH oxidase may be the source of O2•− both intra- and extracellularly. However, even if this is true, we will still need to come to terms with how extracellular O2•− evokes intracellular signaling in SFO neurons. There are a number of possibilities as outlined by the authors, including extracellular O2•−- mediated decreases in nitric oxide (NO•), increases in peroxynitrite, alterations of cell surface proteins via an extracellular redox-sensitive domain, or modification of ionic currents. In support of these latter possibilities, Raizada et al. reported that treatment of primary neurons with exogenous xanthine-xanthine oxidase, an oxidant-generating system, decreases K+ current and increases neuronal firing10. Considering the membrane permeability of the large (~300 kD) xanthine oxidase and its generated O2•− remains unclear, it is possible that these results are in keeping with the idea that extracellular O2•− mediates its effects on K+ current and neuronal firing by acting upon an extracellular redox-sensitive domain of a transmembrane protein such as a receptor or ion channel.

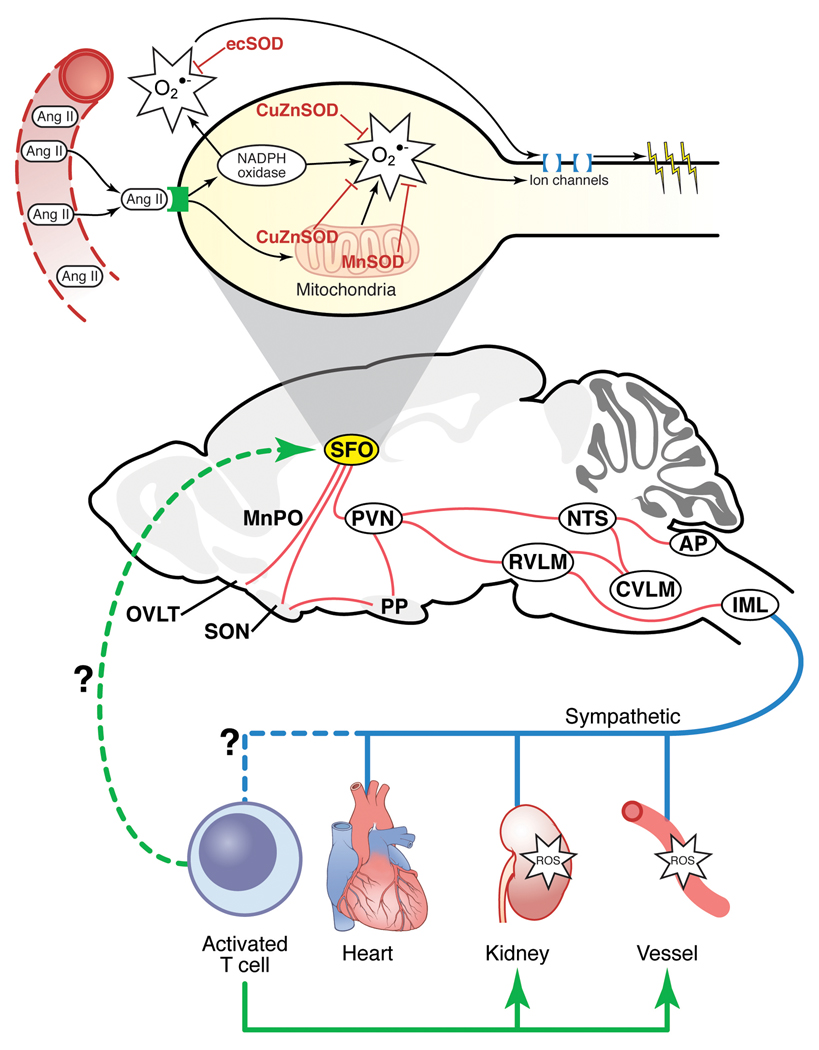

One of the greatest challenges facing the hypertension research community is how to reconcile very convincing findings that the CNS, vasculature and kidney each appears to play a major role in the etiology of this disease. There is no better example of this than that of the Ang-II/oxidant signaling system, which can explain much of the pathophysiology of high blood pressure when studied in the context of these individual organs. The study by Lob et al. requires us to consider that T cell activation via the CVOs may just provide the unifying answer we have been looking for as to how these organ systems are linked and each contribute to the origin of this disease (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Schematic of how the SFO may link central and peripheral mechanisms of Ang-II-dependent hypertension through activation of peripheral T cells.

Perturbations in SOD (CuZnSOD, MnSOD or ecSOD) and/or AngII-mediated activation of NADPH oxidase in the SFO leads to increased oxidant formation and stimulation of downstream sympathoexcitatory circuits. Increased sympathetic nerve firing and/or circulating Ang-II may activate peripheral T cells and expression of homing signals in the vasculature and the kidney. This could promote infiltration of T lymphocytes and oxidant stress-mediated effects on vascular and renal tissues, leading to hypertension. Activated circulating T cells may also act back at the SFO to further promote this cycle.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding

R.L.D. is supported by grants from NIH (HL63887, HL84624 and HL096571) and an Established Investigatorship from the American Heart Association (0540114N). M.C.Z. is supported by NIH (P20RR017675) and an American Heart Association Scientist Development Grant (0930204N).

Footnotes

Disclosures

None.

References

- 1.Buggy J, Fink GD, Johnson AK, Brody MJ. Prevention of the development of renal hypertension by anteroventral third ventricular tissue lesions. Circ Res. 1977;40:I110–I117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnson AK, Gross PM. Sensory circumventricular organs and brain homeostatic pathways. FASEB J. 1993;7:678–686. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.7.8.8500693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lob HE, Marvar PJ, Guzik TJ, Sharma S, McCann LA, Weyand C, Gordon FJ, Harrison DG. Induction of hypertension and peripheral inflammation by reduction of extracellular superoxide dismutase in the central nervous system. Hypertension. 2009 doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.142646. XXX:XXX. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zimmerman MC, Lazartigues E, Lang JA, Sinnayah P, Ahmad IM, Spitz DR, Davisson RL. Superoxide mediates the actions of angiotensin II in the central nervous system. Circ Res. 2002;91:1038–1045. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000043501.47934.fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zimmerman MC, Lazartigues E, Sharma RV, Davisson RL. Hypertension caused by angiotensin II infusion involves increased superoxide production in the central nervous system. Circ Res. 2004;95:210–216. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000135483.12297.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peterson JR, Burmeister MA, Tian X, Zhou Y, Guruju MR, Stupinski JA, Sharma RV, Davisson RL. Genetic silencing of Nox2 and Nox4 reveals differential roles of these NADPH oxidase homologues in the vasopressor and dipsogenic effects of brain angiotensin II. Hypertension. 2009;54:1106–1114. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.140087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zimmerman MC, Sharma RV, Davisson RL. Superoxide mediates angiotensin II-induced influx of extra cellular calcium in neural cells. Hypertension. 2005;45:717–723. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000153463.22621.5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang G, Anrather J, Huang J, Speth RC, Pickel VM, Iadecola C. NADPH oxidase contributes to angiotensin II signaling in the nucleus tractus solitaries. J Neurosci. 2004;24:5516–5524. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1176-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zimmerman MC, Dunlay RP, Lazartigues E, Zhang Y, Sharma RV, Engelhardt JF, Davisson RL. A requirement for Rac1-dependent NADPH oxidase in the cardiovascular and dipsogenic actions of angiotensin II in the brain. Circ Res. 2004;95:532–539. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000139957.22530.b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sun C, Sellers KW, Sumners C, Raizada MH. NAD(P)H oxidase inhibition attenuates neuronal chronotropic actions of angiotensin II. Circ Res. 2005;96:659–666. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000161257.02571.4b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]