Abstract

The goal of this study was to evaluate the clinical and urodynamic features in Korean men with lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) and to determine non-invasive parameters for predicting bladder outlet obstruction (BOO). Four hundred twenty nine Korean men with LUTS over 50 yr of age underwent clinical evaluations for LUTS including urodynamic study. The patients were divided into two groups according to the presence of BOO. These two groups were compared with regard to age, the results of the uroflowmetry, serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level, prostate volume, International Prostate Symptom Score (I-PSS), and the results of the urodynamic study. Patients with BOO had a lower maximal flow rate (Qmax), lower voided volume, higher serum PSA level and larger prostate volume (P<0.05). BOO group had a significantly higher rate of involuntary detrusor contraction and poor compliance compared to the patients without BOO (P<0.05). The multivariate analysis showed that Qmax and poor compliance were significant factors for predicting BOO. Our results show that Qmax plays a significant role in predicting BOO in Korean men with LUTS. In addition, BOO is significantly associated with detrusor dysfunction, therefore, secondary bladder dysfunction must be emphasized in the management of male patients with LUTS.

Keywords: Prostatic Hyperplasia, Urinary Bladder Neck Obstruction, Urodynamics

INTRODUCTION

Bladder outlet obstruction (BOO) is a common cause of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) in elderly men over 50 yr of age (1). BOO results from various etiologic factors that may have functional and anatomical components (2). Because of the complex etiological aspects, the issue of how to accurately evaluate BOO in men with LUTS has been debated for decades (3-5). Thus, when considering management of men with LUTS suggestive of BOO, it is important to take into account the specific aspects of BOO.

Currently, pressure-flow studies (PFS) are widely accepted as the gold standard diagnostic method for identifying BOO (5). Even though PFS is essential for the evaluation of BOO before invasive treatment is considered, many clinicians do not perform PFS as they consider it is invasive, time-consuming and expensive (6). In clinical practice, most often non-invasive methods are used to evaluate men with LUTS such as the maximal flow rate, postvoid residual volume, prostate size, and International Prostate Symptom Score (I-PSS). International guidelines suggest that mandatory and recommended tests are sufficient to conclude the diagnosis of BOO in men with LUTS (7). However, others have argued that these tests are not sufficient for the diagnosis of BOO (8, 9).

In addition, it was suggested that Asian men have a similar frequency of BOO and more severe symptoms despite having a smaller prostate volume (10, 11). However, most literature have been based on the population of Western, and there are few data for the Asian men with LUTS with regard to the clinical features of BOO and the factors that can predict BOO.

Thus, the aim of this study was to evaluate clinical and urodynamic results associated with LUTS in Korean men with BOO and to determine whether non-invasive parameters can be used to predict BOO.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Seoul National University Hospital. All clinical data was prospectively collected from the patients undergoing evaluation for LUTS, between January 2002 and October 2008. All 465 patients with LUTS were enrolled in this study. The exclusion criteria were the following: Patients younger than 50 yr of age, having either prostate cancer or bladder cancer, a previous history of prostate surgery or pelvic radiation, urethral strictures, or any neurological dysfunction that could affect bladder function. Thus, a retrospective analysis was conducted on 429 men with LUTS over 50 yr of age.

The enrolled patients underwent a specific clinical evaluation including medical history, digital rectal examination, focused neurologic examination, I-PSS, urinalysis, serum prostate specific antigen (PSA) level, uroflowmetry, and measurement of postvoid residual volume with ultrasound bladder scan, transrectal ultrasonography, and urodynamic studies including the PFS.

The urodynamic evaluation was performed using a Solar Video Urodynamic system (Medical Measurement Systems B.V., Enschede, the Netherlands), according to the recommendations of the International Incontinence Society Good Urodynamics Practices protocol (12). BOO was determined by the BOOI with the following formula: BOOI=PdetQmax-2Qmax from the PFS (13). The patients were divided into two groups according to the presence of BOO (BOOI ≥40) or the absence of BOO (BOOI <40) (13). We defined the poor compliance of the bladder if its value was less than 40 cmH2O/mL (14).

We compared these two groups with respect to age, maximal flow rate (Qmax), voided volume, postvoid residual volume, serum PSA level, prostate volume, I-PSS, and the urodynamic variables. The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, version 12.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA) was used for the statistical analysis. The patient characteristics were analyzed by the Student's t-test and chi-square test. Univariate analysis was conducted using the chi-square test and linear regression analysis. The multivariate analysis was performed with the bivariate logistic regression. P<0.05 was accepted as statistically significant.

RESULTS

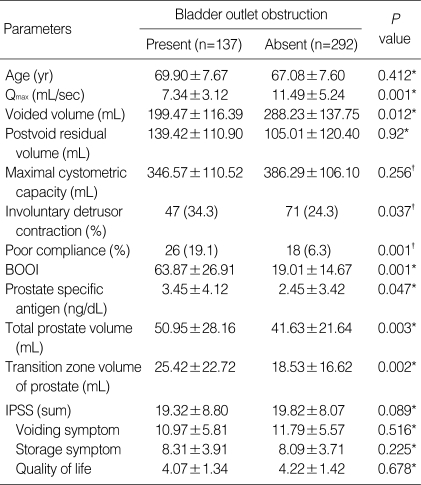

The characteristics of each patient group are shown in Table 1. Patients with BOO had a lower Qmax (7.34±3.12 vs. 11.49±5.24) (P<0.05) and lower voided volume. Also patients with BOO had a higher serum PSA level (3.45±4.12 vs. 2.45±3.42) (P<0.05) and a larger prostate volume (50.95± 28.16 vs. 41.63±21.64) (P<0.05). For the urodynamic parameters, patients with BOO had a significantly higher rate of involuntary detrusor contraction (34.3%, 47/137 vs. 24.3%,71/292) and poor compliance (19.1%, 26/137 vs. 6.3%, 18/292) compared to the patients without BOO. However, no significant differences were found for age, postvoid residual volume, maximal cystometric capacity, and symptom scores between the two groups (P>0.05, Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of clinical parameters between patients with bladder outlet obstruction (BOO) and without BOO

*Student's t-test; †Chi-square test were used for data analysis.

Qmax, maximal flow rate; BOOI, bladder outlet obstruction index; IPSS, International Prostatic Symptom Score.

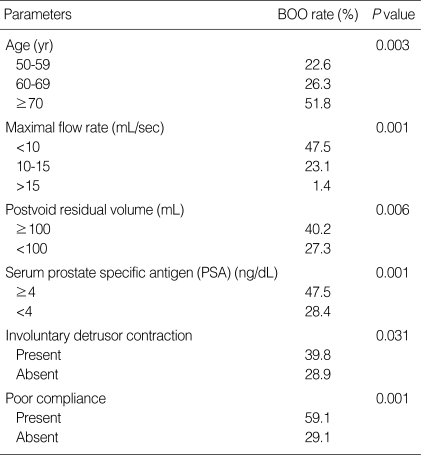

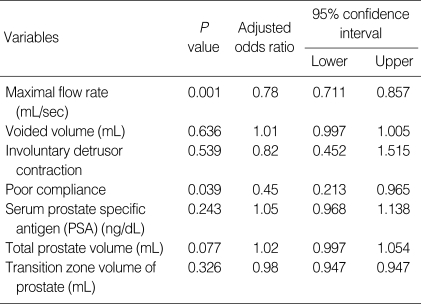

The univariate analysis showed that several parameters had significant predictive value for BOO (Table 2); an older age, increase in the rate of obstruction and a decrease of the Qmax. Patients with BOO had a higher rate of significant postvoid residual volume (more than 100 mL) and serum PSA level (more than 4 ng/dL). The multivariate analysis showed that only Qmax and poor compliance were significant predictive factors for BOO (Table 3).

Table 2.

Univariate analysis of predicting factors for bladder outlet obstruction (BOO) with using chi-square test

Table 3.

Multivariate logistic regression of predicting factors for bladder outlet obstruction

DISCUSSION

The results of this study showed that male LUTS patients with BOO had a higher serum PSA level and a larger prostate volume than those without BOO. Although other investigations reported that prostate volume and serum PSA level were poorly correlated with BOO (15, 16), our results suggest that BOO was associated with prostate size and serum PSA level; these factors may indicate progression of benign prostatic hyperplasia. However, no significant differences were found for age, postvoid residual volume, maximal cystometric capacity, and symptom scores between the men with BOO and those without BOO. In addition, only two parameters, the Qmax and poor compliance, were significant independent predictive factors for BOO by the multivariate analysis. Sonke et al. (17) demonstrated that frequently used diagnostic parameters such as prostate volume, postvoid residual volume and I-PSS were not useful for the prediction of BOO, and the correlation between these parameters and the PFS findings was poor. Vesely et al. (2) reported similar findings; no correlation was noted for the degree of obstruction and the differences in these parameters, in addition to the Qmax. They reported that the simple, non-invasive diagnostic methods were not accurate for the diagnosis of BOO.

On the other hand, Steele et al. (18) showed that combining the symptom scores, maximal flow rate, and prostate volume were useful non-invasive parameters for predicting BOO, although these parameters had poor predictive power when used alone. Tanaka et al. (19) also demonstrated that men with LUTS and BOO can be identified by the prostate volume, Qmax, postvoid residual volume, and I-PSS with a 90% positive predictive value. Thus, the ability of these variables to predict BOO remains controversial.

Recently, other factors used to predict BOO have been reported and include intravesical prostatic protrusion, prostatic urethral angle, and the detrusor wall thickness. Nose et al. (20) suggested that the sensitivity of intravesical prostatic protrusion grade increased in direct proportion to the grade of obstruction; they confirmed that the IPP grading system was useful for the diagnosis of BOO. Oelke et al. (6) conducted a prospective study to find non-invasive tests for the evaluation of BOO; they suggested ultrasound measurements of detrusor wall thickness was better than the Qmax, postvoid residual volume or prostate volume for the diagnosis of BOO. Cho et al. (21) also showed that prostatic urethral angle was an important factor associated with BOO in patients with LUTS; they reported that patients without anatomical obstruction could be successfully treated with a transurethral incision of the bladder neck, which resulted in the resolution of bladder neck elevation. However, these novel methods require further confirmation.

Although not a few urologists treat patients with LUTS suggestive of BOO based on the suspicion of anatomic obstruction due to prostate enlargement, BOO is considered to be often combined with functional factors such as secondary bladder dysfunction (22, 23). If men with LUTS have BOO combined with an overactive bladder, resolution of the obstruction by reduction of the prostate size may not cure the patient's symptom. Consistent with this concept, the present study showed that secondary bladder function changes, such as detrusor overactivity or poor compliance, were more common in patients with BOO. Several investigations have shown that secondary bladder dysfunction was independently associated with BOO (24, 25). The hypothetical explanations for BOO induced bladder dysfunction have been illustrated in animal and human models (26-28). According to prior experimental results, BOO induces marked remodeling of the bladder wall, which includes cellular hypertrophy, hyperplasia and reorganization of the relative structural relationship between connective tissue and smooth muscle elements (26, 27). As the duration of BOO increases, bladder function may decompensate, characterized by functional instability such as an overactive bladder, poor compliance, increasing postvoid residual volume, and decreased contractility (28). Thus, a combination of pathophysiologic factors must be considered when treating men with BOO. Based on the results of present study, we suggest BOO must be treated in males with LUTS as BOO subsequently induces deleterious bladder change. And we are planning to perform further study to investigate the impact of BOO on bladder function.

In conclusion, even though several non-invasive methods used for the evaluation of BOO, only maximal flow rate plays a significant role in predicting of BOO in Korean men with LUTS. Thus, abnormal finding of uroflowmetry indicates the need for performing PFS. In addition, BOO is significantly associated with detrusor dysfunction, therefore, secondary bladder dysfunction must be emphasized in the management of male patients with LUTS suggestive of BOO.

References

- 1.Dmochowski RR. Bladder outlet obstruction: etiology and evaluation. Rev Urol. 2005;7(Suppl 6):S3–S13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vesely S, Knutson T, Fall M, Damber JE, Dahlstrand C. Clinical diagnosis of bladder outlet obstruction in men with lower urinary tract symptoms: reliability of commonly measured parameters and the role of idiopathic detrusor overactivity. Neurourol Urodyn. 2003;22:301–305. doi: 10.1002/nau.10128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boormans JL, van Venrooij GE, Boon TA. Invasively estimated International Continence Society obstruction classification versus noninvasively assessed bladder outlet obstruction probability in treatment recommendation for LUTS suggestive of BPH. Urology. 2007;69:485–490. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ozawa H, Chancellor MB, Ding YY, Nasu Y, Yokoyama T, Kumon H. Noninvasive urodynamic evaluation of bladder outlet obstruction using Doppler ultrasonography. Urology. 2000;56:408–412. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(00)00684-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nitti VW. Pressure flow urodynamic studies: the gold standard for diagnosing bladder outlet obstruction. Rev Urol. 2005;7(Suppl 6):S14–S21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oelke M, Höfner K, Jonas U, de la Rosette JJ, Ubbink DT, Wijkstra H. Diagnostic accuracy of noninvasive tests to evaluate bladder outlet obstruction in men: detrusor wall thickness, uroflowmetry, postvoid residual urine, and prostate volume. Eur Urol. 2007;52:827–834. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.AUA Practice Guidelines Committee. AUA guideline on management of benign prostatic hyperplasia (2003). Chapter 1: diagnosis and treatment recommendations. J Urol. 2003;170:530–547. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000078083.38675.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Homma Y, Gotoh M, Takei M, Kawabe K, Yamaguchi T. Predictability of conventional tests for the assessment of bladder outlet obstruction in benign prostatic hyperplasia. Int J Urol. 1998;5:61–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.1998.tb00238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sirls LT, Kirkemo AK, Jay J. Lack of correlation of the American Urological Association Symptom 7 Index with urodynamic bladder outlet obstruction. Neurourol Urodyn. 1996;15:447–456. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6777(1996)15:5<447::AID-NAU2>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choi J, Ikeguchi EF, Lee SW, Choi HY, Te AE, Kaplan SA. Is the higher prevalence of benign prostatic hyperplasia related to lower urinary tract symptoms in Korean men due to a high transition zone index? Eur Urol. 2002;42:7–11. doi: 10.1016/s0302-2838(02)00222-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsukamoto T, Kumamoto Y, Masumori N, Miyake H, Rhodes T, Girman CJ, Guess HA, Jacobsen SJ, Lieber MM. Prevalence of prostatism in Japanese men in a community-based study with comparison to a similar American study. J Urol. 1995;154:391–395. doi: 10.1097/00005392-199508000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schäfer W, Abrams P, Liao L, Mattiasson A, Pesce F, Spangberg A, Sterling AM, Zinner NR, van Kerrebroeck P. Good urodynamic practices: uroflowmetry, filling cystometry, and pressure-flow studies. Neurourol Urodyn. 2002;21:261–274. doi: 10.1002/nau.10066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abrams P. Bladder outlet obstruction index, bladder contractility index and bladder voiding efficiency: three simple indices to define bladder voiding function. BJU Int. 1999;84:14–15. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1999.00121.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abrams P. Urodynamic techniques. In: Abrams P, editor. Urodynamics. 3rd ed. Bristol: Springer; 2006. pp. 67–72. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Madersbacher S, Klingler HC, Djavan B, Stulnig T, Schatzl G, Schmidbauer CP, Marberger M. Is obstruction predictable by clinical evaluation in patients with lower urinary tract symptoms? Br J Urol. 1997;80:72–77. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1997.00220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Belal M, Abrams P. Noninvasive methods of diagnosing bladder outlet obstruction in men. part 1: nonurodynamic approach. J Urol. 2006;176:22–28. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(06)00569-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sonke GS, Heskes T, Verbeek AL, de la Rosette JJ, Kiemeney LA. Prediction of bladder outlet obstruction in men with lower urinary tract symptoms using artificial neural networks. J Urol. 2000;163:300–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steele GS, Sullivan MP, Sleep DJ, Yalla SV. Combination of symptom score, flow rate and prostate volume for predicting bladder outflow obstruction in men with lower urinary tract symptoms. J Urol. 2000;164:344–348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tanaka Y, Masumori N, Itoh N, Tsukamoto T, Furuya S, Ogura H. The prediction of bladder outlet obstruction with prostate volume, maximum flow rate, residual urine and the international prostate symptom score in patients with lower urinary tract symptoms. Hinyokika Kiyo. 2001;47:843–847. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nose H, Foo KT, Lim KB, Yokoyama T, Ozawa H, Kumon H. Accuracy of two noninvasive methods of diagnosing bladder outlet obstruction using ultrasonography: intravesical prostatic protrusion and velocity-flow video urodynamics. Urology. 2005;65:493–497. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2004.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cho KS, Kim JH, Kim DJ, Choi YD, Kim JH. Relationship between prostatic urethral angle and urinary flow rate: its implication in benign prostatic hyperplasia pathogenesis. Urology. 2008;71:858–862. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2008.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Knutson T, Edlund C, Fall M, Dahlstrand C. BPH with coexisting overactive bladder dysfunction- an everyday urological dilemma. Neurourol Urodyn. 2001;20:237–247. doi: 10.1002/nau.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wadie BS, Ebrahim el-HE, Gomha MA. The relationship of detrusor instability and symptoms with objective parameters used for diagnosing bladder outlet obstruction: a prospective study. J Urol. 2002;168:132–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oelke M, Baard J, Wijkstra H, de la Rosette JJ, Jonas U, Höfner K. Age and bladder outlet obstruction are independently associated with detrusor overactivity in patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Eur Urol. 2008;54:419–426. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sullivan MP, Yalla SV. Detrusor contractility and compliance characteristics in adult male patients with obstructive and nonobstructive voiding dysfunction. J Urol. 1996;155:1995–2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levin RM, Haugaard N, O'Connor L, Buttyan R, Das A, Dixon JS, Gosling JA. Obstructive response of human bladder to BPH vs. rabbit bladder response to partial outlet obstruction: a direct comparison. Neurourol Urodyn. 2000;19:609–629. doi: 10.1002/1520-6777(2000)19:5<609::aid-nau7>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mirone V, Imbimbo C, Longo N, Fusco F. The detrusor muscle: an innocent victim of bladder outlet obstruction. Eur Urol. 2007;51:57–66. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.07.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Agartan CA, Whitbeck C, Chichester P, Kogan BA, Levin RM. Effect of age on rabbit bladder function and structure following partial outlet obstruction. J Urol. 2005;173:1400–1405. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000149033.92717.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]