Abstract

Histiocytic sarcoma (HS) is a very rare neoplasm that often shows an aggressive clinical course and systemic symptoms, such as fever, weight loss, adenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly and pancytopenia. It may present as localized or disseminated disease. We describe here a 63-yr-old male who manifested systemic symptoms, including fever, weight loss and generalized weakness. Abdominal and chest computed tomography failed to show specific findings, but there was suspicion of multiple bony changes at the lumbar spine. Fusion whole body positron emission tomography, bone scan and lumbar spine magnetic resonance imaging showed multiple bone lesions, suggesting a malignancy involving the bone marrow (BM). Several BM and bone biopsies were inconclusive for diagnosis. Necropsy showed replacement of the BM by a diffuse proliferation of neoplastic cells with markedly increased cellularity (95%). The neoplastic cells were positive for lysozyme and CD68, but negative for T- and B-cell lineage markers, and megakaryocytic, epithelial, muscular and melanocytic markers. Morphologic findings also distinguished it from other dendritic cell neoplasms.

Keywords: Histiocytic Sarcoma, Bone Marrow

INTRODUCTION

Histiocytic sarcoma (HS), a rare hematopoietic neoplasm with aggressive characteristics and poor outcomes, can present as localized disease confined to the skin, lymph nodes, and intestinal tract, or as disseminated disease (1, 2). These histiocytic and dendritic cell neoplasms arise from antigen-processing phagocytes and antigen-presenting dendritic cells, cells derived from hematopoietic or mesenchymal stem cells (1). HS has often been mistaken for some types of lymphomas, due to their overlapping features and inadequate phenotypic evaluation, particularly immunohistochemical and cytogenetic data (2, 3). Current HS diagnosis is based on histological and immunohistochemical evidence of histiocytic differentiation and the exclusion of epithelial, melanocytic, and lymphoid phenotypes (4). Using both immunohistochemistry and cytogenetics, it is now generally accepted that most neoplasms diagnosed as HS were actually B- or T-cell, non-Hodgkin lymphomas (1, 4).

HS is a malignancy characterized by the proliferation of histiocytes with positive expression of the macrophage associated antigen CD68; negative expression of the T-cell associated and Langerhans cell antigen CD1a, S-100 protein, and the dendritic cell-associated antigens CD21 and CD35; and also the absence of Birbeck granules, junctions, desmosomes and cytoplasmic projections on electron microscopy (1-6). Although several cases of HS have been described (4-12), primary bone marrow (BM) involvement is rare. We describe here a patient with HS showing primary BM involvement.

CASE REPORT

A 63-yr-old male complaining of weight loss (10 kg in 6 months), fever of unknown origin and general weakness was referred to our hospital for evaluation. Previous medical history, family history and physical examination showed nothing remarkable. At presentation, white blood cell (WBC) count was 13.2×103/µL, hemoglobin was 9.4 g/dL and platelet count was 466×103/µL. Prothrombin time and activated partial thromboplastin time were near normal range. His serum protein concentration was 7.5 mg/dL, albumin was 1.4 mg/dL, aspartate aminotransferase was 53 IU/L, alanine aminotransferase was 53 IU/L, alkaline phosphatase was 496 IU/L, γ-GT was 66 IU/L, total bilirubin was 0.7 mg/dL, lactate dehydrogenase was 231 IU/L and C-reactive protein was 26.42 mg/dL. Sodium concentration in serum was 129 mM/L, potassium was 4.4 mM/L, chloride was 93 mM/L and total CO2 was 29.0 mM/L. His ferritin concentration was 2,339.3 ng/mL and fibrinogen concentration was 552 mg/dL. Review of abdominal and chest computed tomography (CT) performed at the referring hospital showed nothing unusual, except for a few 1-cm-sized small lymph nodes and mild hepatosplenomegaly. Head and neck CT revealed slight enlargement of a neck lymph node, which may have been benign or metastatic, but two target biopsies and an excisional biopsy of the lesion provided no diagnostic information. Abdominal and pelvic CT performed at our hospital showed the same results as the CT scans performed at the referring hospital, except for suspicion of bony changes at the lumbar and sacral bones.

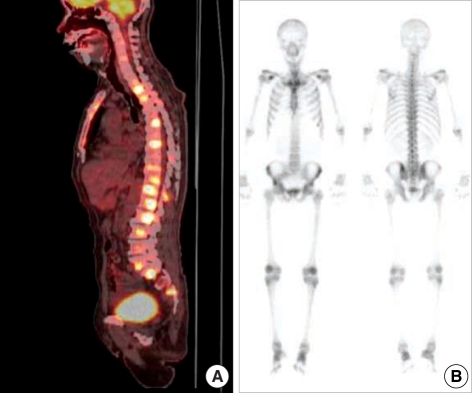

Although fusion whole body positron emission tomography (PET) showed lesions indicative of multiple bone metastases (Fig. 1A), a bone scan showed little osteoblastic reaction (Fig. 1B). Because there was no evidence of malignancy on chest, abdominal and pelvic CT and prostate ultrasonography, we performed lumbar spine magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Fig. 2). The MRI findings suggested that the PET lesions were reactive changes of the BM caused by malignant cell infiltration, such as leukemia, lymphoma or multiple myeloma (MM) rather than multiple bone metastases.

Fig. 1.

Scanning findings for bones. (A) Disseminated hypermetabolic lesion (maxSUV=9.0, L2 body) at the whole spine by PET. A hypermetabolic lesion suggesting a primary malignant lesion was not detected in the lung, intraabdominal and pelvic organs. (B) No increased bone uptake of hypermetabolic lesions on bone scan, with little osteoblastic effect.

Fig. 2.

Diffuse and heterogeneous T1 and T2 showing low SI changes in the lower thoracic and lumbar spine with subtle enhancement.

A BM biopsy showed an increase in plasma cells (15%), eosinophils and histiocytes, but no malignant cells. Due to suspected MM, we tested the monoclonality of the plasmacytosis and fluorescence in situ hybridization myeloma panel. Although β2-microglobulin was 3.6 mcg/mL, there was no evidence of monoclonality in plasmacytosis, IGH/FGFR3 rearrangement, or RB1 or TP53 deletion. The serum concentration of kappa free light chain (FLC) was 81.10 mg/L, the serum concentration of lambda FLC was 139.00 mg/L and the kappa/lambda FLC ratio was 0.58. Serum protein electrophoresis and immunoelectrophoresis showed increases in α-1, 2 and γ-globulin fractions, findings consistent with a chronic inflammatory response. CT guided bone biopsies of the lumbar spine and another BM biopsy showed no evidence of malignant cells. The patient chose supportive care, but was readmitted one month later for aggravation of his general condition. Abdominal and pelvic CT showed no changes except for apparent bony changes. The patient still wanted supportive care and died soon afterward.

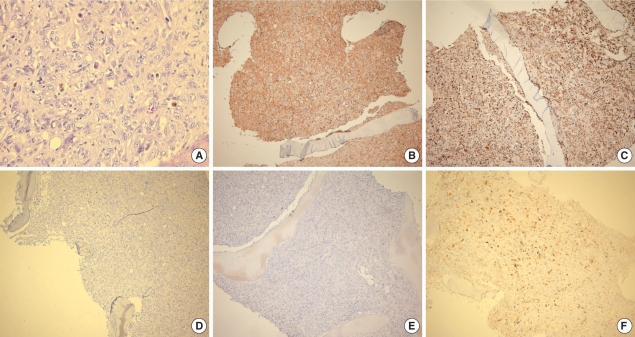

At necropsy, we performed another BM biopsy and a liver biopsy. The liver biopsy showed no evidence of malignancy, except for severe cholestasis with non-specific hepatitis. The BM biopsy, however, revealed a diffuse non-cohesive proliferation of pleomorphic neoplastic cells with large round to oval nuclei, vesicular chromatin and abundant foamy eosinophilic cytoplasm (Fig. 3). Immunohistochemistry showed positive expression of CD68 (macrophage/histiocytic marker), S100 protein, CD31, CD99 and Vimentin. Neoplastic cells were weakly positive for CD21 (mature B-cell and follicular dendritic cell marker), CD4 (T-cell marker) and lysozyme and negative for CD3 (T-cell marker), CD20/CD79a (B-cell markers), CD56 (NK cell marker), cytokeratin, smooth muscle actin (SMA, a myeloid cell marker), SMMHC and HMB45. Staining showed Masson-Trichrome positive fine collagen fibers and PAS positivity on megakaryocytes. Together, these morphologic and immunohistochemical features are consistent with the BM involvement of HS.

Fig. 3.

Histopathological findings of bone marrow biopsy. (A) Non-cohesive proliferation of large pleomorphic neoplastic cells with large round-to-oval nuclei with vesicular chromatin and abundant foamy cytoplasm (H&E stain, ×400). Immunostaining with antibodies to (B) CD99, (C) CD68, (D) CD56, (E) HMB45 (each, ×100) and (F) S100 (×200).

DISCUSSION

HS is a rare and aggressive malignant disorder commonly presenting at extranodal sites and showing a poor response to therapy, with most patients dying from the disease (1). Some patients show systemic presentation, with features of malignant histiocytosis. HS may also be associated with other hematological disorders, such as acute leukemia, lymphoma and myelodysplasia (1, 7). Genetic or epigenetic inactivation of PTEN, p16INK4A, and p14ARF has been observed in HS, indicating that these proteins are involved in the development of HS and providing insights into the pathogenesis of these tumors (13).

Differential diagnosis of HS includes Langerhans cell sarcoma (LCS), diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, peripheral T-cell lymphoma, anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL), metastatic carcinoma, and melanoma. The diagnosis of HS is based on histological and immunohistochemical evidence of histiocytic differentiation and exclusion of other malignancies with epithelial, melanocytic and lymphoid phenotypes (4). Malignant HS cells strongly express the hemoglobin scavenger marker CD163, which is regarded as a specific marker for HS (4).

Tumor cells in our patient showed expression of histiocytic markers (CD68) and lysozyme with weak expression of CD21. The cells, however, did not express B-cell, T-cell, and myeloid markers, including CD3, CD20, CD56, and CD79a, or SMA and SMMHC. The expression of histiocytic markers was unusual for ALCL, and no rearrangement of the T-cell receptor γ-chain gene was identified. Although these cells showed expression of S100 protein, the latter may have been derived from activated normal macrophages (1, 9). Metastatic carcinoma and melanoma were ruled out by the absence of expression of cytokeratins and HMB45 (9).

Morphologically, tumor cells in LCS have nuclei that are grooved, indented, folded, or lobulated, with fine chromatin and a thin nuclear membrane, features that are absent in HS (2, 9). The tumor cells in our patient had abundant clear cytoplasm, without spindle or fusiform cells, showing a whorled, fascicular or storiform pattern. These morphologic differences could distinguish the disease in our patient from LCS, and from follicular and interdigitating dendritic cell tumors (1).

HS shows a very aggressive clinical course in most patients. In one study, 6 of 11 patients died of disease within 0.5 to 36 months (10). In a study of 18 patients who underwent chemotherapy, 3 achieved complete remission, 6 had no response, and 7 died of disease (1). In another study of four adult patients with widespread disease, all failed chemotherapy and died from disease within 0.5 to 14 months after diagnosis (14). In other studies, 6 of 8 adult patients died of disease 5 to 48 months after diagnosis despite aggressive chemotherapy (15). The patient described here died of disease 2 months after his first visit to our hospital.

Due to the rarity of this malignancy, chemotherapy regimens have not been standardized, with most studies being retrospective reviews (8). Nonetheless, chemotherapy used to treat large cell lymphomas is a reasonable approach for patients with HS (12), although thalidomide may also benefit these patients (3, 11).

In summary, HS is a rare neoplasm difficult to pathologically diagnose. Immunohistochemical features suggesting HS include the strong expression of histiocytic markers such as CD68, lysozyme and CD163. Proper recognition of HS is important, because the clinical presentation and morphologic appearance of this neoplasm may lead to a misdiagnosis as other hematologic malignancies.

References

- 1.Pileri SA, Grogan TM, Harris NL, Banks P, Campo E, Chan JK, Favera RD, Delsol G, De Wolf-Peeters C, Falini B, Gascoyne RD, Gaulard P, Gatter KC, Isaacson PG, Jaffe ES, Kluin P, Knowles DM, Mason DY, Mori S, Muller-Hermelink HK, Piris MA, Ralfkiaer E, Stein H, Su IJ, Warnke RA, Weiss LM. Tumours of histiocytes and accessory dendritic cells: an immunohistochemical approach to classification from the International Lymphoma Study Group based on 61 cases. Histopathology. 2002;41:1–29. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2002.01418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weiss LM, Grogan TM, Muller-Hermelink HK, Stein H, Dura WT, Favara B, Pauli M, Feller AC. Histiocytic sarcoma. In: Jaffe ES, Harris NL, Stein H, Vardiman JW, editors. WHO Classification of Tumors: Pathology and Genetics of Tumors of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. 2nd ed. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2001. pp. 278–279. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abidi MH, Tove I, Ibrahim RB, Maria D, Peres E. Thalidomide for the treatment of histiocytic sarcoma after hematopoietic stem cell transplant. Am J Hematol. 2007;82:932–933. doi: 10.1002/ajh.20913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vos JA, Abbondanzo SL, Barekman CL, Andriko JW, Miettinen M, Aguilera NS. Histiocytic sarcoma: a study of five cases including the histiocyte marker CD163. Mod Pathol. 2005;18:693–704. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buonocore S, Valente AL, Nightingale D, Bogart J, Souid AK. Histiocytic sarcoma in a 3-year-old male: a case report. Pediatrics. 2005;116:e322–e325. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang SC, Chang CL, Huang CH, Chang CC. Histiocytic sarcoma-a case with evenly distributed multinucleated giant cells. Pathol Res Pract. 2007;203:683–689. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2007.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feldman AL, Minniti C, Santi M, Downing JR, Raffeld M, Jaffe ES. Histiocytic sarcoma after acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: a common clonal origin. Lancet Oncol. 2004;5:248–250. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(04)01428-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alexiev BA, Sailey CJ, McClure SA, Ord RA, Zhao XF, Papadimitriou JC. Primary histiocytic sarcoma arising in the head and neck with predominant spindle cell component. Diagn Pathol. 2007;2:7. doi: 10.1186/1746-1596-2-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fukunaga M, Kato H. Histiocytic sarcoma associated with idiopathic myelofibrosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004;128:1167–1170. doi: 10.5858/2004-128-1167-HSAWIM. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kamel OW, Gocke CD, Kell DL, Cleary ML, Warnke RA. True histiocytic lymphoma: a study of 12 cases based on current definition. Leuk Lymphoma. 1995;18:81–86. doi: 10.3109/10428199509064926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dalle JH, Leblond P, Decouvelaere A, Yakoub-Agha I, Preudhomme C, Nelken B, Mazingue F. Efficacy of thalidomide in a child with histiocytic sarcoma following allogeneic bone marrow transplantation for T-ALL. Leukemia. 2003;17:2056–2057. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hornick JL, Jaffe ES, Fletcher CD. Extranodal histiocytic sarcoma: clinicopathologic analysis of 14 cases of a rare epithelioid malignancy. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:1133–1144. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000131541.95394.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carrasco DR, Fenton T, Sukhdeo K, Protopopova M, Enos M, You MJ, Di Vizio D, Nogueira C, Stommel J, Pinkus GS, Fletcher C, Hornick JL, Cavenee WK, Furnari FB, Depinho RA. The PTEN and INK4A/ARF tumor suppressors maintain myelolymphoid homeostasis and cooperate to constrain histiocytic sarcoma development in humans. Cancer Cell. 2006;9:379–390. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ralfkiaer E, Delsol G, O'Connor NT, Brandtzaeg P, Brousset P, Vejlsgaard GL, Mason DY. Malignant lymphomas of true histiocytic origin. A clinical, histological, immunophenotypic and genotypic study. J Pathol. 1990;160:9–17. doi: 10.1002/path.1711600105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lauritzen AF, Delsol G, Hansen NE, Horn T, Ersboll J, Hou-Jensen K, Ralfkiaer E. Histiocytic sarcomas and monoblastic leukemias. A clinical, histologic, and immunophenotypical study. Am J Clin Pathol. 1994;102:45–54. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/102.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]