Abstract

1-chloroalkynes and 1-bromohexyne undergo cycloaddition reactions with ethoxyvinylketeneiron(0) complexes to form chloro and bromocatechols. With most substituents, the halogen is incorporated ortho to the phenolic hydroxyl group regioselectively. With chloroethyne, chlorohexyne, and methyl chloropropiolate, the reverse regioselection is observed. Ab initio calculations reveal that the products are, in most cases, nearly isoenergetic, which indicates that the intermediate ketene-alkyne adduct geometry must be important in determining the product distribution.

The efficient, regiospecific synthesis of highly substituted aromatic rings represents an important challenge in organic synthesis.1 One convergent approach is the [4+2] cycloaddition of vinylketenes2 with alkynes, however vinylketenes are usually unstable and undergo [2+2] cycloaddition upon reaction with alkynes as well as themselves. The parent compound, vinylketene (buta-1,3-dienone) dimerizes in a hetero [4+2] cycloaddition.3 Masked vinylketenes have been used to carry out this transformation, but often require a deprotection step.4 Danheiser used silicon stabilized vinylketenes in Diels-Alder cycloaddition reactions with alkynes.5 Electrocyclic ring closures of dienyl ketenes, generated in situ from cyclobutenones, have been developed by Moore,6a Danheiser,6b and Liebeskind.6c Danheiser also reported a formal [4+2] reaction of 2-silylvinylketenes with ynolates to form monosilylated resorcinol derivatives.7

Transition metals, through their ability to stabilize reactive intermediates, offer powerful alternatives for the synthesis of highly substituted aromatic systems. The reaction of Fischer carbene complexes with alkynes to form hydroquinones has been extensively studied and modified.8 A wealth of evidence indicates that this important transformation proceeds through the intermediacy of vinylketene complexes. Chromium promoted variants of the electrocyclization of dienylketenes have also been exploited by Merlic9a,b and Wulff,9c who first isolated an η4-vinylketene chromium complex from the reaction of a Fischer carbene complex with an alkyne.10 Liebeskind reported the synthesis of phenols from alkynes and cobalt-complexed vinylketenes, which were prepared from cyclobutenones,11 and subsequently discovered a nickel catalyzed variation.12 Recently, Kondo and Mitsudo reported a rhodium catalyzed reaction.13 These methods use vinylketenes generated from cyclobutenones, limiting their utility. The availability of isolable η4-vinylketene iron complexes from a variety of sources14 provides a promising solution to the cycloaddition problem given the low cost of iron.15 One noteworthy advantage of iron over chromium in benzannulation reactions is the fact that the product arenes are not complexed to the metal as they often are with chromium. Gibson prepared η4-complexed vinylketene iron(0) complexes from η4-vinylketone-iron(0) complexes,16 however the major products of reactions of alkynes with these complexes were alkyne insertion products, which formed cyclopentenediones, and, rarely, phenols.17 Treatment of the insertion products with FeCl3 resulted in furan-3-(2H)-ones and reactions with CO produced cyclopentenediones and butenolides.18

Our early studies indicated that both electron poor (i.e. ester, ketone, and trifluoromethyl substituted) and electron rich alkynes (i.e. ynol ethers) readily undergo cycloadditions with vinylketene iron complexes to form catechol monoethyl ethers upon reaction with 1a (Table 1, R1 = Ph).19 Tam recently reported ruthenium catalyzed [2+2] cycloadditions20a of norbornenes with alkynyl halides, and rhodium catalyzed intramolecular [4+2] cycloadditions20b of haloalkyne tethered dienes, which inspired us to examine the reactions of terminal haloalkynes with vinylketene iron(0) complexes. Our results are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Cyclization of Vinylketeneiron(0) Complexes with 1-haloalkynesa

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Complex | R2 | X | Product (%) |

ΔEb (kcal/m ol) |

| 1 | 1a | Bu | Br | 3a (28)c | |

| 2 | 1a | H | Cl | 4b (33)d | 3b 1.1 |

| 3 | 1a | Cl | Cl | 3c (45)d | |

| 4 | 1a | cyc-Pr | Cl | 3d (62) | 4d 0.2 |

| 5 | 1a | t-Bu | Cl | 3e (55) | |

| 6 | 1a | t-Bu | Cl |

3e (44) 4e(11)e |

|

| 7 | 1a | Bu | Cl | 4f (72) | |

| 8 | 1a | Ph | Cl | 3g (62) | 4g-0.8 |

| 9 | 1a | SiMe3 | Cl | 3h (42) | 4h-3.5 |

| 10 | 1a | COOMe | Cl |

3i (14) 4i (23)f |

3i 5.6 |

| 11 | 1b | Bu | Cl | 4j (49) | |

| 12 | 1b | Ph | Cl | 3k (43) | |

Unless otherwise stated all reactions were carried out with 0.3-1.5 mmol of vinylketene complex with 1.0 equivalent of haloalkyne in 3-15 mL THF heated at reflux for 24-48 h.

Positive (negative) value indicates 3 (4) is more stable.

DMF, reflux 48 h.

Volatile alkynes were used in excess as solutions that were heated at 70° C in pressure vessels equipped with Young valves.

Reaction was carried out at 90°C.

Dechlorinated product, 4i with X = H, was also obtained in 39 % yield.

Initially, we compared the reactions of 1-iodohexyne, 1-bromohexyne, and 1-chlorohexyne with 1a. Heating 1a with iodohexyne for 96 h in DMF at 120 °C provided mostly unreacted iodohexyne with two putative cycloadducts (m/z = 396), which were detected by GC-MS. Bromohexyne was more promising, giving 3a in 5% yield after refluxing in THF for 24 h. Heating 1a with bromohexyne in DMF at reflux for 48 h produced the bromocatechol 3a in 28% yield. A NOESY experiment was used to verify the structure. Reaction of one equivalent of chlorohexyne with 1a in THF produced 4f in 72% yield. Cyclotrimers were not a significant contributor to the mass balance of the reactions, although detectable quantities of cyclotrimerization products were found with GC-MS in the Single Ion Monitoring (SIM) mode.

We focused our subsequent efforts in this preliminary study on 1-chloroalkynes. For chloroethyne (entry 2), chlorohexyne (entry 7), and methyl chloropropiolate (entry 10), the chlorine of the major product was incorporated meta to the phenolic hydroxyl group. An intermediate was isolated from the reaction of chloroethyne with 1a, which exhibited proton and carbon NMR spectra consistent with the alkyne insertion product, (Scheme 1, compound 6, R1 = Ph, R2 = Et, R3= H). Injection (300 °C) into the GC-MS provided a peak with retention time and mass coincident with 4b. Thermolysis of a sample at 110 °C for 24 h in THF resulted in complete conversion to 4b. In the other compounds studied to date the chlorine was found ortho to the phenolic hydroxyl. Reaction with chloroethynyl cyclopropane (entry 4) didn't produce any ring opening product, suggesting that a slow radical reaction is unlikely. Although most reactions were carried out in refluxing THF, reaction with tert-butylethynyl chloride at 90 °C (entry 6) produced both isomers of the cycloadduct in a 1:4 ratio, indicating that regioselection is temperature dependent. GC-MS analysis of aliquots taken from a reaction of 1a with chlorohexyne (entry 7) revealed that formation of the product 4f was detectable after a few minutes at room temperature.

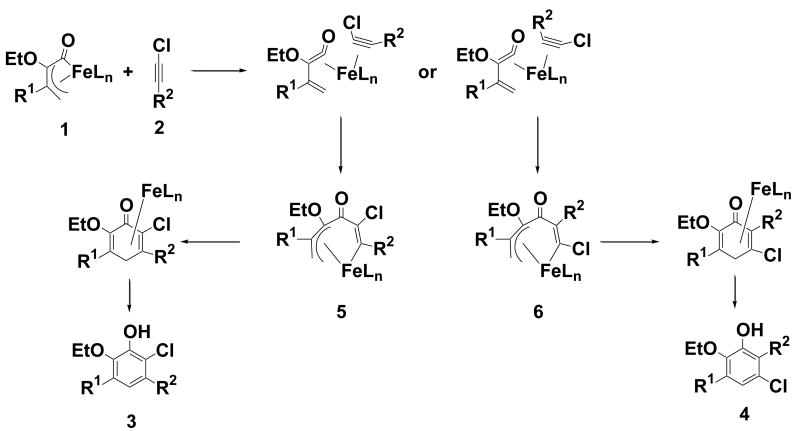

Scheme 1.

Proposed mechanism of formation of chlorocatechols.

The reaction with methyl chloropropiolate (entry 10) was complicated by dechlorination resulting in a lower yield of halocatechol. GC-MS studies are consistent with the observation that the dechlorination occurs after incorporation of the chloroalkyne. Reaction of 1a with methyl propiolate provided large amounts of the two cyclotrimers, neither of which was not observed in this reaction, suggesting that dechlorination may not be occuring prior to reaction with the vinylketene complex. GC-MS analysis of aliquots taken from this reaction showed initial formation of the desired product soon after the reaction was started. The dechlorinated catechol was not detected until after 24 hours and then increased at the expense of the desired product. Trace amounts of dechlorination product were detected (GC-MS) with chloroethynyltrimethylsilane, chlorohexyne, and chloroethyne.

Complex 1b behaved similarly, but it was noted that under reaction conditions similar to those used with the phenyl complex, unreacted 1b was isolated along with pyrocatechols even after extended reaction times. Again, the regioselectivity appears to be controlled primarily by steric effects. The regioselectivity exhibited in this study is most often precisely the opposite exhibited by the Dötz benzannulation8 of chromium carbene complexes: the more sterically demanding substituent is incorporated meta rather than ortho to the inserted carbonyl group which forms the phenol.

A mechanism is suggested in Scheme 1. Formation of a coordinatively unsaturated iron complex through decomplexation of one of the π bonds of the diene leads to formation of the η2 alkyne complex.21 It seems most likely that the regioselectivity is established when the η2-complex forms the insertion product. Analogy with the work of Gibson 17, 18, 22 suggests that insertion occurs first at the ketene carbonyl rather than at the terminal allylic carbon of the vinylketene. Reductive elimination to form a cyclohexadienone, followed by tautomerization provides the catechol.

In an attempt to understand the regioselectivity of the products, ab initio calculations are performed for various alkynes and some of the products. The Löwdin population analysis on the chloroalkyne at the various levels of the theory shows the general trend for the alkyne carbon connected to R2 is electron-rich or electron-deficient in accordance with the electronegativity difference between chlorine and the R2 group. Therefore, the product distribution in Table 1 cannot be understood by the alkyne electronic structure. The thermodynamic stability of the products alone does not explain the product distribution, either. As shown in Table 1, using the MP2/6-31G(d,p) level of theory including the zero-point energy from the RHF/6-31G(d,p) level, R2 = H, cyclo-Pr, and Ph substituted model products are nearly isoenergetic. In the case of R2 = SiMe3, 4h is more stable than 3h by 3.5 kcal/mol. The largest difference among the calculated products is R2 = COOH, and 3i is 6 kcal/mol more stable than 4i. The major products of the latter two substitutions are in fact opposite of what thermodynamic stability of the products should be. From these considerations, it is likely that steric factors in the formation of reactive intermediates play a more important role in the formation of the observed products. Hence the ketene-alkyne adduct geometry must be important in determining the product distribution, and we are currently investigating this aspect computationally. We are actively probing the electronic and steric parameters that influence the regioselectivity.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge financial support through an Intramural Research Grant to N.M. and W.F.K.S. and a grant to W.F.K.S. from the NIH (SC2GM082276). The NSF provided funds for the purchase of a GC-MS (CHE-0840432). We also thank the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry of Rutgers University, Newark for access to instrumentation. We thank Mr. William. A. Helwig, Mr. Ruhul Q. Chowdhury, Ms. Kerry McKenzie, Mr. Dean Aquino, and Ms. Jeunesse Lewis (Harlem Childrens Society intern) for assistance.

Footnotes

Supplementary data: Supplementary data (detailed experimental procedures, spectroscopic data, NMR spectra, and details of ab initio calculations associated with this article can be found), in the online version, at doi:

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.An entire issue of Tetrahedron 2008, 64, 757-968 focuses on the use of benzannulation and cycloaddition reactions to form aromatic rings.

- 2.For a comprehensive review of ketene chemistry see: Tidwell TT. Ketenes. Wiley; New York: 1995.

- 3.Trahanovsky WS, Surber BW, Wilkes MC, Preckel MM. J Am Chem Soc. 1982;104:6779–6781. and references therein.

- 4.Corey EJ, Kozikowski AP. Tetrahedron Lett. 1975;16:2389–2392. [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Loebach JL, Bennett DM, Danheiser RL. J Org Chem. 1998;63:8380–8389. [Google Scholar]; (b) Danheiser RL, Sard H. J Org Chem. 1980;45:4810–4812. [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Moore HW, Decker OHW. Chem Rev. 1986;86:821–830. [Google Scholar]; (b) Sun L, Danheiser RL, Brisbois RG, Kowalczyk JJ, Miller RF. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:3093–3100. [Google Scholar]; (c) Liebeskind LS. J Org Chem. 1995;60:8194–8203. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Austin WF, Zhang Y, Danheiser RL. Org Lett. 2005;7:3905–3908. doi: 10.1021/ol051307b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.For a comprehesive review of the Dötz benzannulation see: Waters ML, Wulff WD. Org React. 2008;70:121–623., and for a general updated review see Dötz KH, Stendal J., Jr Chem Rev. 2009;109:3227–3274. doi: 10.1021/cr900034e.

- 9.(a) Merlic CA, Aldrich CC, Albaneze-Walker J, Saghatelian A, Mammen J. J Org Chem. 2001;66:1297–1309. doi: 10.1021/jo0014663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Merlic C, Xu D, Gladstone BG. J Org Chem. 1993;58:538–545. [Google Scholar]; (c) Rawat M, Wulff WD. Org Lett. 2004;6:329–332. doi: 10.1021/ol0360445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anderson BA, Wulff WD, Rheingold AL. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:8615–8617. [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Huffman MA, Liebeskind LS, Pennington WT. Organometallics. 1992;11:255–266. [Google Scholar]; (b) Huffman MA, Liebeskind LS. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:8617–8618. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huffman MA, Liebeskind LS. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:2771–2772. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kondo T, Niimi M, Nomura M, Wada K, Mitsudo T. Tetrahedron Lett. 2007;48:2837–2839. [Google Scholar]

- 14.For a comprehensive review of vinylketene complexes see: Gibson SE, Peplow MA. Adv Organomet Chem. 1999;44:275–353..

- 15.For recent reviews of iron chemistry in organic synthesis see: Sherry BD, Fürstner A. Acc Chem Res. 2008;41:1500–1511. doi: 10.1021/ar800039x. and Bolm C, Legros J, Le Paih J, Zani L. Chem Rev. 2004;104:6217–6254. doi: 10.1021/cr040664h..

- 16.Alcock NW, Richards CJ, Thomas SE. Organometallics. 1991;10:231–238. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morris KG, Saberi SP, Thomas SE. J Chem Soc; Chem Commun. 1993:209–211. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saberi SP, Salter MM, Slawin AMZ, Thomas SE, Williams DJ. J Chem Soc; Perkin Trans. 1994;1:167–171. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Akhani RK, Rehman A, Schnatter WFK. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009;50:930–932. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2008.12.037. and Darbasie ND, Schnatter WFK, Warner KF, Manolache N. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006;47:963–966..

- 20.Villeneuve K, Ridell N, Jordan RW, Tsui GC, Tam W. Org Lett. 2004;6:4543–4546. doi: 10.1021/ol048111g. and Allan A, Villenueve K, Cockburn N, Fatila E, Riddell N, Tam W. Eur J Org Chem. 2008:4178–4192.. Yoo WJ, Allen A, Villeneuve K, Tam W. Org Lett. 2005;7:5853–5856. doi: 10.1021/ol052412o.

- 21.Diphenylketene-alkyne Ir(I) complexes have been shown to undergo cyclization to form iridabenzopyrans: Lo HC, Grotjahn DB. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:2958–2959.

- 22.Benyunes SA, Gibson (née Thomas) SE, Peplow MA. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 1997;8 and references therein.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.