Abstract

Chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans (CSPGs) present a barrier to axon regeneration. However, no specific receptor for the inhibitory effect of CSPGs has been identified. We showed that a transmembrane protein tyrosine phosphatase, PTPσ, binds with high affinity to neural CSPGs. Binding involves the chondroitin sulfate chains and a specific site on the first immunoglobulin-like domain of PTPσ. In culture, PTPσ−/− neurons show reduced inhibition by CSPG. A PTPσ fusion protein probe can detect cognate ligands that are up-regulated specifically at neural lesion sites. After spinal cord injury, PTPσ gene disruption enhanced the ability of axons to penetrate regions containing CSPG. These results indicate that PTPσ can act as a receptor for CSPGs and may provide new therapeutic approaches to neural regeneration.

Recovery after central nervous system (CNS) injury is minimal, leading to substantial current interest in potential strategies to overcome this challenge (1–5). Chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans (CSPGs) show dramatic up-regulation after neural injury, within the extracellular matrix of scar tissue and in the perineuronal net within more-distant targets of the severed axons (6, 7). The inhibitory nature of CSPGs is reflected not only in the formation of dystrophic axonal retraction bulbs that fail to regenerate through the lesion (8), but also in the limited capacity for collateral sprouting of spared fibers (8, 9). This inhibition can be relieved by chondroitinase ABC digestion of the chondroitin sulfate (CS) side chains, which can promote regeneration and sprouting and restore lost function (10–14). It has been known for nearly two decades that sulfated proteoglycans are major contributors to the repulsive nature of the glial scar (15); however, the precise inhibitory mechanism remains poorly understood. Because the identification of specific neuronal receptors for CSPGs has been lacking, relatively nonspecific mechanisms brought about by arrays of negatively charged sulfate (16) or the occlusion of substrate adhesion molecules (17) have been suggested.

Transmembrane protein tyrosine phosphatases (PTPs) form a large and diverse molecular family and have a structure typical of transmembrane cell-surface receptors (18, 19). In previous work, we and others have found that PTPσ and other PTPs in the leukocyte antigen–related (LAR) subfamily can act as receptors for heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) (20–22), and these PTPs are involved in axon guidance and synapse formation during development (18–22). In the adult, PTPσ gene disruption enhances regeneration in sciatic, facial, and optic nerves (23–25), although the mechanism for this enhancement has not been clear.

Finding that LAR subfamily PTPs are developmental receptors for HSPGs led us to investigate whether they might also be receptors for CSPGs. The CSPGs and HSPGs are analogous structurally, both consisting of a core protein bearing negatively charged sulfated carbohydrate side chains. To test for binding, we used PTPσ together with neurocan/CSPG3, a major CSPG that is produced by reactive astroglia after CNS injury (26) (Fig. 1A). Using a cell-free system with recombinant fusion proteins of the PTPσ extra-cellular domain with an immunoglobulin Fc tag (PTPσ-Fc) and neurocan with an alkaline phosphatase tag (Ncn-AP), a binding interaction was indeed identified (P < 0.001) (Fig. 1B). Genuine biological ligand-receptor interactions are expected to show saturability and high affinity. Adding increasing amounts of Ncn-AP to PTPσ-Fc showed that the interaction is saturable (Fig. 1D), and Scatchard analysis produced a linear plot, indicating a single binding affinity with a dissociation constant (KD) of approximately 11 nM (Fig. 1E). Binding was also demonstrated with aggrecan, another astroglial CSPG, producing a KD of approximately 19 nM (fig. S1). These KDs are similar to those we measured previously for the functional binding of Drosophila LAR to the HSPG ligands with which it interacts during development (22), and the values are within the typical nanomolar range for biologically significant ligand-receptor interactions.

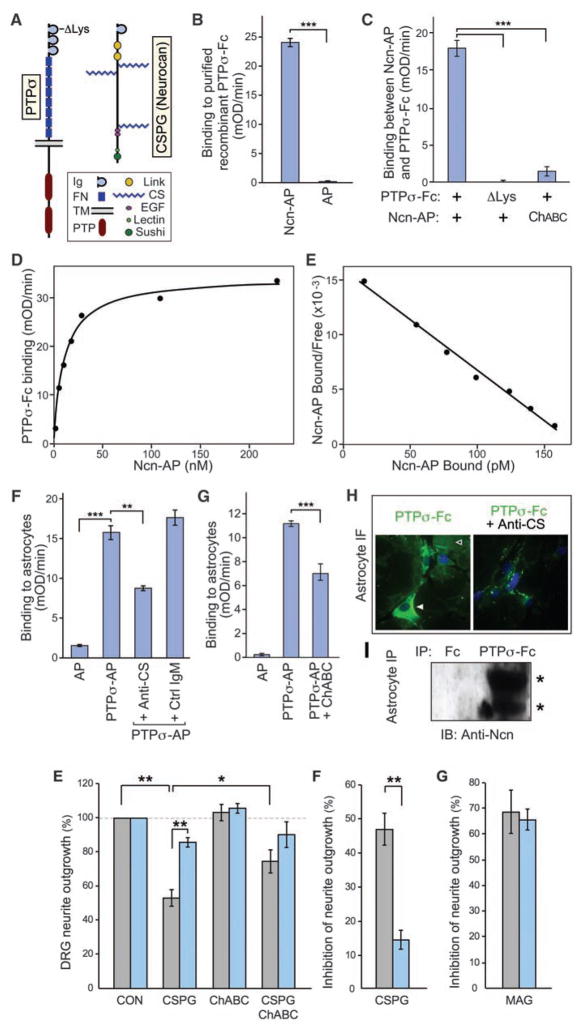

Fig. 1.

Binding of the PTPσ ectodomain to CSPG. (A) Domain structure of PTPσ and the CSPG neurocan. ΔLys indicates the site in PTPσ where a cluster of lysines was mutated. (B to E) Purified recombinant PTPσ-Fc fusion protein was immobilized and treated with Ncn-AP fusion protein or AP tag control, followed by quantitation of bound AP activity. (B) Ncn-AP bound above control levels. (C) The PTPσ ΔLys mutation reduced binding to background levels. Pretreatment of Ncn-AP with chondroitinase ABC (ChABC) reduced binding. (D) Binding between PTPσ-Fc and Ncn-AP was saturable. (E) Scatchard analysis produced a linear plot, indicating a single binding affinity with KD = 11 nM. (F) PTPσ-AP bound to C8-D1A astrocyte cultures above AP control levels. Binding was reduced by antibody to CS (anti-CS), but not by an immunoglobulin M (IgM) control. (G) Chondroitinase ABC pretreatment of astrocyte cultures reduced PTPσ-AP binding. (H) PTPσ-Fc immunofluorescence (green) showed binding over cell surfaces (solid arrowhead) and extracellular matrix (open arrowhead); Fc control gave no visible fluorescence (not shown in the figure). Pre-incubation with anti-CS reduced binding. Blue is nuclear counter-stain. (I) PTPσ-Fc, but not Fc control, coprecipitated neurocan from C8-D1A astrocyte lysates. Western blot showed bands with expected sizes for neurocan proteolytic fragments at approximately 150 and 100 kD (asterisks). ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01.

The CS moiety plays an important role in CSPG-mediated inhibition of neural regeneration (10, 12, 15, 16). We therefore tested whether the CS moiety of neurocan is involved in its interaction with PTPσ. Pretreatment of the Ncn-AP fusion protein with chondroitinase ABC abolished most binding to PTPσ, confirming involvement of the CS chains (P < 0.001; Fig. 1C). Some binding remained, which might be due to incomplete digestion by chondroitinase ABC, which leaves a stub of CS. Other experiments showed that PTPσ binds to isolated CS chains (fig. S1). While it is possible that PTPσ might also interact with the core protein of CSPGs, these experiments indicate an involvement of the CS chains.

We also investigated the binding site on PTPσ. PTPσ has a conserved, positively charged region on the surface of the first immunoglobulin-like domain, and mutations of basic residues at this site impair binding of heparan sulfate (HS) (20). Because CS, like HS, is a negatively charged carbohydrate, it seemed plausible that this site might also bind CS. A cluster of four lysine residues in this domain, K67, K68, K70, and K71, were substituted with alanines (the ΔLys mutant of PTPσ; Fig. 1A). This substitution reduced binding to background levels (P < 0.001; Fig. 1C and fig. S1), identifying a CS interaction site on PTPσ.

To further address biological relevance, we examined whether PTPσ interacts with CSPG that is produced endogenously by astroglia, a cell type that produces inhibitory CSPGs at sites of neural injury. Because CS chains are added posttranslationally, using a relevant cell type could confirm binding with appropriately modified endogenous CSPGs. These experiments used mouse C8-D1A astrocytes, which express neurocan, display it on the cell surface, and deposit proteolytically processed neurocan fragments into the extracellular matrix (27). PTPσ fusion proteins were indeed found to bind astrocyte cultures, as shown by quantitative binding (P < 0.001; Fig. 1F) and immunofluorescence (Fig. 1H). Also, PTPσ-Fc coimmunoprecipitated neurocan fragments from astrocytes (Fig. 1I). The involvement of CS chains was confirmed by pretreatment of astrocytes with chondroitinase ABC or by pre-blocking with antibody to CS (P < 0.01; Fig. 1, F to H). These treatments did not eliminate all PTPσ binding, suggesting either that the treatments were only partially effective or that PTPσ may bind to molecular epitopes other than CS, such as keratan sulfate chains. In any case, the role of CS in this interaction makes it likely that PTPσ binds not only to neurocan and aggrecan but also to other CSPGs produced by astrocytes.

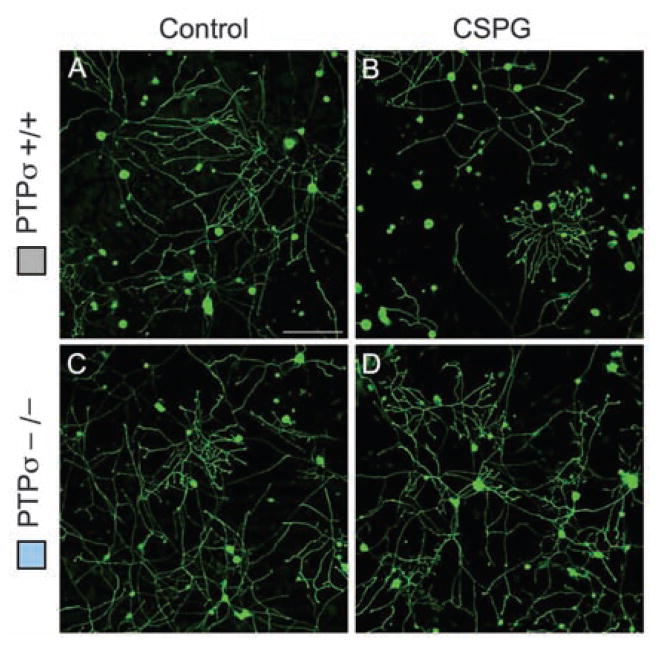

Having identified a binding interaction between PTPσ and CSPGs, we next tested whether PTPσ is functionally involved in the inhibitory effects of CSPG on neurons. Dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons express high levels of PTPσ throughout life (28). Postnatal day 8 (P8) DRG neurons from mice with a targeted gene disruption of PTPσ (29) or from wild-type controls were cultured in the presence of a neural CSPG mixture (Fig. 2) or purified neurocan (fig. S2). The CSPG mixture reduced control DRG neurite outgrowth by approximately 50% (Fig. 2, A, B, E, and F) but had far less effect on neurons from PTPσ−/− mice (P < 0.01; Fig. 2, C to F), showing a functional involvement of PTPσ in the response of young DRG neurons to inhibitory CSPGs. Comparable results were seen when neurons were challenged with purified neurocan (P < 0.001; fig. S2). The observation of some remaining inhibitory effect of CSPGs on PTPσ−/− neurons (Fig. 2F and fig. S2E) suggests the possible presence of additional receptors, which could be other PTPs in the LAR family or receptors in other families, or there could be additional receptor-independent mechanisms. To address the role of CS chains, the CSPG mixture was pretreated with chondroitinase ABC. This reduced its inhibitory effect on wild-type DRG neurons (P < 0.05) but did not cause a significant effect on PTPσ−/− neurons; thus, the outgrowth difference between wild-type and PTPσ−/− neurons was no longer statistically significant (Fig. 2E). This is consistent with our results showing that CS chains are involved in binding to PTPσ (Fig. 1 and fig. S1). Finally, we assessed whether the effect of PTPσ deficiency shows specificity for CSPG. We tested myelin-associated glycoprotein (MAG), a different inhibitory molecule (2), as well as nerve growth factor (NGF), which can oppose the effect of myelin-associated inhibitors (30). PTPσ deficiency did not affect neurite outgrowth in response to either MAG (Fig. 2G; P = 0.75) or NGF (fig. S3; P = 0.67 without NGF; P = 0.99 with NGF). Thus, PTPσ shows a specific functional role in the inhibitory response of DRG neurons to CSPG.

Fig. 2.

Effect of PTPσ deficiency on the response of sensory neurons to CSPG. (A to D) DRG neurons from P8 mice were grown for 18 hours, then treated for 24 hours with or without CSPG and visualized by GAP-43 immunolabeling. (E) Quantitation of neurite outgrowth. PTPσ−/− neurons showed significantly less inhibition by CSPG than wild-type neurons did. A significant difference was no longer seen when chondroitinase ABC was added along with the CSPG. (F and G) Effect of CSPG or MAG, expressed as percentage of inhibition of outgrowth. PTPσ deficiency reduced the inhibitory action of CSPG but had no significant effect on the inhibitory action of MAG. n = 5 mice for each genotype. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. Scale bars, 100 μm.

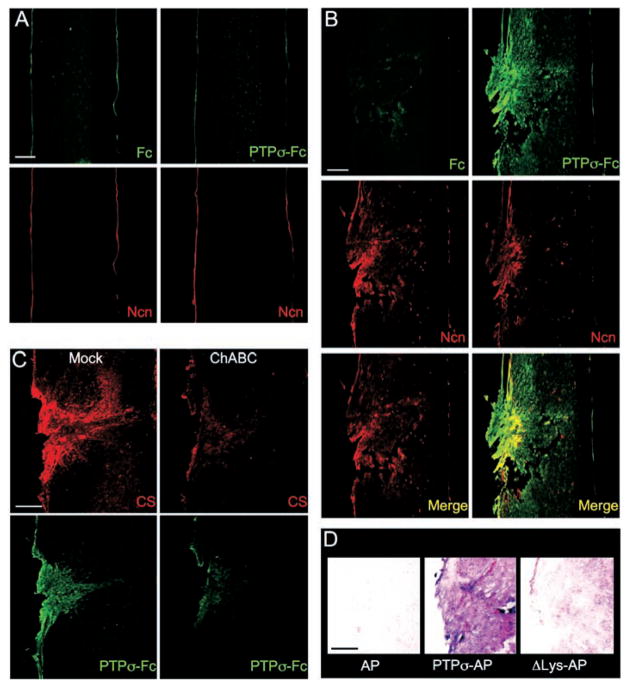

We next tested whether PTPσ has appropriate binding specificity to detect endogenous CSPG at sites of neural injury. In particular, we wanted to know whether PTPσ could preferentially recognize injured versus uninjured adult CNS tissue; this cannot be deduced simply from PTPσ’s ability to bind CSPGs (Fig. 1), because PTPσ also binds HSPGs and, potentially, other ligands. Receptor ectodomain fusion proteins can be used to detect the distribution of their cognate ligands in tissues (31). PTPσ-Fc did not show obvious binding above background on uninjured spinal cord (Fig. 3A), whereas it showed strong binding around the lesion site 1 week after spinal cord injury (Fig. 3B). PTPσ-Fc labeling overlapped with neurocan immunolabeling, which was also induced by injury as expected (Fig. 3B), although the patterns were not identical. PTPσ-Fc appeared to label additional areas, which is consistent with binding to additional CSPGs. Binding was reduced by chondroitinase ABC treatment or by use of the PTPσ ΔLys mutant (Fig. 3, C and D), once again demonstrating involvement of the CS moiety. These binding results on spinal cord provide further evidence for the role of PTPσ as a CSPG receptor and also show that it has appropriate binding specificity to serve biologically as a selective detector for injury sites in the adult CNS.

Fig. 3.

PTPσ fusion protein detection of ligand distribution at a spinal cord lesion site. (A and B) Sections were double–fluorescence-labeled with antibody to neurocan (Ncn, red), together with either PTPσ-Fc probe (green) or Fc control (adjacent section, green). (A) Unlesioned spinal cord. Anti-neurocan labeled a thin line at the pia. PTPσ-Fc showed no labeling noticeably above Fc control levels. (B) Spinal cord 7 days after dorsal hemisection. The lesion site showed simultaneous elevation of neurocan immunolabeling and PTPσ-Fc binding. The distributions overlapped, with PTPσ-Fc labeling additional areas. (C) ChABC treatment reduced binding of PTPσ-Fc to the lesion site. Adjacent sections were preincubated with or without ChABC, then double-labeled with anti-CS (red) and PTPσ-Fc (green). (D) Introduction of ΔLys mutation into a PTPσ-AP probe reduced lesion site binding (purple) close to AP tag control levels. Scale bars, 200 μm.

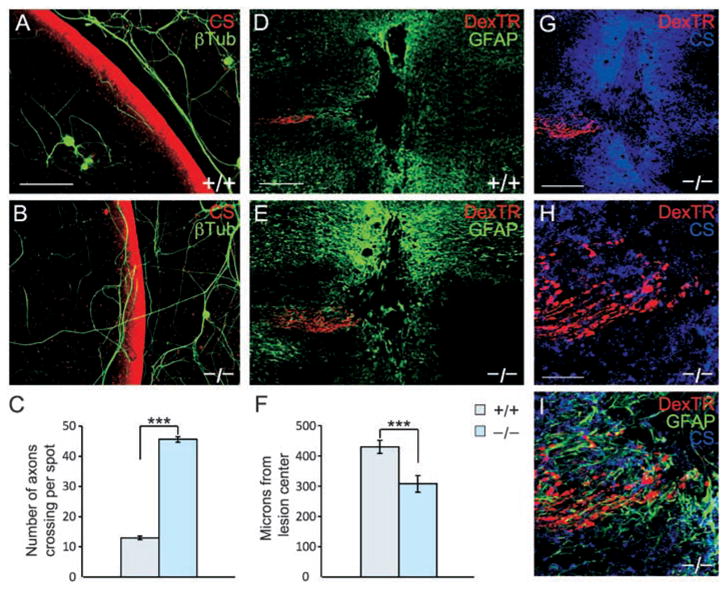

To test further for relevance to spinal cord injury, we used two functional models. After spinal cord injury, reactive glia produce an increasing gradient of CSPG beginning in the lesion penumbra and increasing toward the epicenter. In vivo, regenerating axons within this gradient stall and display dystrophic growth cone morphology (32). The dystrophic growth cone can be produced in vitro when neurons are exposed to a gradient of CSPG (8). We found a fourfold increase in PTPσ−/− neurites crossing the inhibitory outer rim of the gradient versus wild-type controls (P < 0.001; Fig. 4, A to C). We also used an in vivo spinal cord injury model, performing a dorsal column crush injury on adult mice and examining the position of labeled sensory axons in the fasciculus gracilis 14 days later. In the PTPσ−/− mice, axon extension into the lesion penumbra was significantly improved (P < 0.002; Fig. 4, D to F, and fig. S4). PTPσ−/− axons extended well into the region of inhibitory proteoglycan surrounding the lesion (Fig. 4, G to I). However, similar to the effect of chondroitinase (10), robust regeneration beyond the core of the lesion did not occur. This might, in principle, reflect partial redundancy with other PTPs in the LAR subfamily, and it would also be consistent with the known presence of other growth impediments such as the myelin inhibitors (1–5) and factors intrinsic to unconditioned neurons (33, 34). The results in this regeneration model system demonstrate a role for PTPσ in mediating the axonal response to the inhibitory CSPG-rich scar in a spinal cord lesion in vivo.

Fig. 4.

Adult PTPσ−/− sensory neurons show reduced sensitivity to inhibition by a proteoglycan gradient and can extend further in a spinal cord lesion. (A and B) Adult wild-type DRG neurons visualized by antibody to β-tubulin (green) avoided the most inhibitory rim of the gradient visualized by anti-CS (red). PTPσ−/− neurons showed greater ability to cross the rim. (C) Quantitation of the average number of axons per spot growing up the gradient and crossing the outer rim. Wild-type, n = 48 spots; PTPσ−/−, n = 40 spots; ***P < 0.001. (D and E) Confocal images of longitudinal sections from adult mouse spinal cord 14 days after dorsal column crush, caudal to the left. Sensory axons are labeled with DexTR (red), and the lesion is delineated by glial fibrillary acidic protein+ (GFAP+) astrocytes (green). Wild-type axons are seen several hundred micrometers from the lesion center; PTPσ−/−axons abut the edge of the lesion core. (F) Quantitation of distance from lesion center. Wild-type, n = 35 mice; PTPσ−/−, n = 30 mice. ***P < 0.002. (G to I) Confocal z-stack images of PTPσ−/− mouse dorsal column crush lesion, showing relationship between injured fibers (red), anti-CS labeling (blue), and in (I), reactive astrocytes (green). Scale bars in (A) and (B), 100 μm; in (D) and (E), 200 μm; in (G) to (I), 50 μm.

It has long been recognized that CSPG is one of the major inhibitors of neural regeneration; however, the mechanism has been poorly understood, and it has been unclear whether the mechanism even involves specific cellular receptors, limiting the options to tackle this important area by molecular approaches. Finding that PTPσ is a functional receptor that binds and mediates actions of CSPGs opens the door to new molecular approaches to understand CSPG action not only in regeneration, but also in development and plasticity. Our work on PTPσ also sheds new light on functions of the PTP family, and it will be interesting to know whether the other PTPs of the LAR subfamily may collaborate in nerve regeneration. The finding that a PTPσ fusion protein can detect lesion sites in the adult CNS not only sheds light on the biological role of PTPσ but also provides an injury biomarker, and thus a potential tool for research or diagnosis. Furthermore, the identification of a specific site on PTPσ that binds CSPG provides a lead for potential drug design to treat spinal cord injury. Alternative blocking approaches, such as soluble receptor ectodomains, could be used, and such approaches could potentially be combined with the blockade of other regeneration inhibitors. In addition to the possible treatment of spinal cord injury, the results here may be relevant to many other forms of neural injury as well as neurodegeneration that involves reactive astrogliosis. Identifying a functional receptor for a major class of regeneration inhibitors provides new pathways for research into mechanisms and therapeutic interventions to enhance regeneration or plasticity after nervous system injury.

Note added in proof: While this paper was in press, an additional characterization of the PTPσ gene knockout was published. Fry et al. (35) studied the corticospinal tract and reported regeneration after both surgical and contusive lesions, further contributing to the evidence in the present paper and previous studies that PTPσ acts in multiple areas of the nervous system and can play a key role in regeneration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

36. We thank M. Tremblay for the PTPσ mouse strain; D. Van Vactor, M. Osterfield, Y. Chen, P. Hess, P. Brittis, J. Tcherkezian, N. Preitner, and D. Nowakowski for discussions; and the Harvard Medical School Nikon Imaging Center staff for expert assistance with imaging.

References and Notes

- 1.Case LC, Tessier-Lavigne M. Curr Biol. 2005;15:R749. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Domeniconi M, Filbin MT. J Neurol Sci. 2005;233:43. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2005.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu BP, Cafferty WB, Budel SO, Strittmatter SM. Philos Trans R Soc London Ser B. 2006;361:1593. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2006.1891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lu P, Tuszynski MH. Exp Neurol. 2008;209:313. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yiu G, He Z. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:617. doi: 10.1038/nrn1956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Silver J, Miller JH. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:146. doi: 10.1038/nrn1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rhodes KE, Fawcett JW. J Anat. 2004;204:33. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2004.00261.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tom VJ, Steinmetz MP, Miller JH, Doller CM, Silver J. J Neurosci. 2004;24:6531. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0994-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Massey JM, et al. J Neurosci. 2006;26:4406. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5467-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bradbury EJ, et al. Nature. 2002;416:636. doi: 10.1038/416636a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cafferty WB, et al. J Neurosci. 2008;28:11998. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3877-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Houle JD, et al. J Neurosci. 2006;26:7405. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1166-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pizzorusso T, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:8517. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602657103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tester NJ, Howland DR. Exp Neurol. 2008;209:483. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Snow DM, Lemmon V, Carrino DA, Caplan AI, Silver J. Exp Neurol. 1990;109:111. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4886(05)80013-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gilbert RJ, et al. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2005;29:545. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2005.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McKeon RJ, Hoke A, Silver J. Exp Neurol. 1995;136:32. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1995.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chagnon MJ, Uetani N, Tremblay ML. Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;82:664. doi: 10.1139/o04-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson KG, Van Vactor D. Physiol Rev. 2003;83:1. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00016.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aricescu AR, McKinnell IW, Halfter W, Stoker AW. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:1881. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.6.1881-1892.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fox AN, Zinn K. Curr Biol. 2005;15:1701. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson KG, et al. Neuron. 2006;49:517. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McLean J, Batt J, Doering LC, Rotin D, Bain JR. J Neurosci. 2002;22:5481. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-13-05481.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sapieha PS, et al. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2005;28:625. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2004.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thompson KM, et al. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2003;23:681. doi: 10.1016/s1044-7431(03)00120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Asher RA, et al. J Neurosci. 2000;20:2427. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-07-02427.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chan CC, Wong AK, Liu J, Steeves JD, Tetzlaff W. Glia. 2007;55:369. doi: 10.1002/glia.20466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haworth K, Shu KK, Stokes A, Morris R, Stoker A. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1998;12:93. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1998.0707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Elchebly M, et al. Nat Genet. 1999;21:330. doi: 10.1038/6859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gao Y, et al. Neuron. 2004;44:609. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Flanagan JG, et al. Methods Enzymol. 2000;327:19. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(00)27264-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Davies SJA, et al. Nature. 1997;390:680. doi: 10.1038/37776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goldberg JL, Klassen MP, Hua Y, Barres BA. Science. 2002;296:1860. doi: 10.1126/science.1068428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Neumann S, Woolf CJ. Neuron. 1999;23:83. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80755-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fry EJ, et al. Glia. 2009 doi: 10.1002/glia.20934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.