Abstract

Epidemiological studies suggest that consumption of isoflavones rich diets can improve several postmenopausal complications. The aim of this study was to investigate the absorption and the efficacy of isoflavonic supplementation in the treatment of menopausal symptoms.

36 postmenopausal women received 75 mg/day of isoflavones in the form of tablets, for six months. 21 subjects concluded the treatment. Plasmatic and urinary samples were collected before and after the treatment, along with a dietary interview. Isoflavones were determined in biological samples and in commercial administered supplements by a HPLC/DAD system.

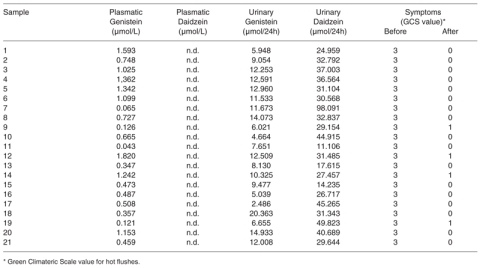

Results showed the presence of genistein (from 0.043 to 1.820 micromol/L) in plasma samples, and of genistein (from 2.486 to 20.363 micromol/24h) and daidzein (from 11.106 to 98.091 micromol/24h) in the urines of the treated women. In the 21 completers the Greene Climateric scale value for hot flushes changed from 3 to 1 or 0. No changes of the endometrial thickness and of the breast tissue were detected. The analysis of the supplement content in the tablets was in agreement with what declared by the producer.

Administration of isoflavone supplements produced a decrease of symptoms in this cohort of postmenopausal women monitored for isoflavone absorption.

Keywords: phytoestrogens, isoflavones, HPLC analysis, menopause, hot flushes.

Introduction

Phytoestrogens are a group of polyphenolic compounds derived from plants that bear a similarity to estrogens in their chemical structure and biological properties (1). The soy isoflavones, genistein and daidzein, are the most extensively studied compounds (2). The main sources of these compounds are in the order, traditional soy foods, second generation soy foods, gluten-free aliments, legumes like broad beans, red beans, fresh podded peas, red clover sprouts, some species of Solanaceae, and milk of red clover fed cows (3-7). The aglicone is the available chemical form for intestinal absorption, as such or in a more hydrophilic form bound to a molecule of glucuronic or sulphuric acid (8). The conjugated molecules can pass the enterohepatic circle (9) and return at the intestinal level where they are converted into different metabolites (10). The pharmacokinetic analysis of isoflavones in humans supported the theoretical model of their enterohepatic recirculation, suggesting that this mechanism is the way used to increase their “in vivo” half-life (11). The metabolites that do not enter in the enterohepatic recycle are eliminated through the urines, while the final metabolites are eventually eliminated in small quantities with the faeces (12). Usually the urinary excretion for daidzein is higher than for genistein and this can be explained for its facility to take the biliary route (13). In the absorption efficiency of isoflavones, the intestinal flora plays an important role at three different levels: hydrolysis of glucosides, degradation and conjugation. However, the intestinal bacterial population responsible for these functions has not been identified yet (10).

The role of the intestinal flora in determining the bioavailability of isoflavones is supported by the fact that every variable that affects the intestinal microenviroment (antibiotics, laxatives, intestinal diseases) can modify the metabolism of these compounds, making of the healthy intestinal condition a prerequisite for phytoestrogen administration.

Another factor recognized to influence the phytoestrogen bioavailability is the genetic difference in the capability to metabolize these molecules. Indeed, in humans only 30-50% of the treated subjects is able to produce equol from daidzein and 80-90% of this group can produce O-desmethylangolensin (ODMA) (9). The capacity to produce equol is increased in the equol-producers subjects fed with a diet rich in carbohydrates and fibres and poor in fats and, therefore, capable to increase the intestinal fermentation (11).

Other conditions capable to influence the bioavailability of isoflavones are the alimentary matrix even though the absorption facilitator complex for phytoestrogens is unknown (14). Another variable is the type of administration, with microencapsulation representing an ideal vehicle (15). Factors that appear not critical for influencing isoflavone absorption are age and gender (16, 17).

Once absorbed isoflavones have a half-life of eight hours (18), shorter than expected for compounds capable to generate several metabolites (19). The pharmacokinetic profile does not appear influenced by chronic exposition to soy or soy-derivatives, supporting the fact that these compounds do not bioaccumulate in the organism (20).

According with their biological features, isoflavones are able to carry out four main types of actions on estrogen-sensitive targets: no effect, an estrogenic effect, an anti-estrogenic effect and effects non estrogenic, but unique for these molecules (21). Genistein and daidzein are capable to bind to estrogen receptors (ERs) with an affinity respectively 100 and 1000 folds lower than 17β estradiol (22) and with a greater affinity for estrogen receptors β (ERβ) than ERα (23). Bone, brain, bladder and vascular vessels are rich in ERβ, while breast, uterus and ovary express both ERα or ERβ. This different localization of ERs can explain the capacity of isoflavones to determine a selective action on the different target tissues. Antiestrogenic effects of phytoestrogens are correlated with their capability to repress estrogenic metabolic enzymes [i.e. aromatase (24), 17β hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase, and 3β hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (25)]. Finally, non estrogenic mechanisms of action of these molecules are: a) the inhibition of angiogenesis (26) and of cellular proliferation through the control of tyrosine kinase and topoisomerase II enzymes (27), and b) the antioxidant actions and the capability to modulate the production of nitric oxide (28).

Dietary intake of isoflavones is estimated to be around 20-100 mg/day in Asians (29), while Europeans do not exceed 1 mg/day (0.63-1 mg/day in men and 0.49-0.66 mg/day in women) (1). In particular classes of consumers, like vegetarians, hypercholesterolemics, children and infants, the intake of phytoestrogens is higher because of their diet composition (30).

Epidemiological studies suggest that consumption of an isoflavone-rich diet, common in the traditional Asian diet, is associated with an improvement both of many of the postmenopausal complications [cardiovascular diseases (31), osteoporosis (32-34), hormone-dependent cancers (35),

Alzheimer’s disease (36), and diabetes (31)] and of the neurovegetative symptoms [hot flushes, night sweats, irritability, insomnia, and mood changes (37)]. Because hormone replacement therapy (HRT), that effectively prevents a number of these problems, shows a poor long-term adherence, research focused an alternative remedies, such as phytoestrogens.

In this study, we have selected 36 postmenopausal women who received a daily administration of an analytically dosed phytoestrogenic supplement during a period of six months. In this population isoflavonic metabolites were measured in plasma and urines before starting the supplementation and after six months of treatment, with a careful monitoring of the neurovegetative symptoms and of the mammary and uterine tissues.

Materials and methods

Study subjects

36 volunteers postmenopausal women (mean age 56.4 years), selected among 242 female patients, were examined at the gynecology outpatient Clinic of the Bone Metabolic Unit of the University of Florence from March to June 2006. The postmenopausal status was determined on the basis of plasmatic FSH values (up to 30 UI/ml) and amenorrhoea status up to 6 months. Recruitment criteria included: the presence of severe menopausal symptoms, in particular hot flushes [score 3 of the modified Greene Climateric Scale; (38)], endometrial thickness ≤4 mm, lack of osteoporosis, and normal serum cholesterol levels. All the women were informed on the phytoestrogen therapy, in general well accepted because of the common belief of being “more natural” than HRT (39). Only one subject (n 7) of the group had been previously using phytoestrogenic therapy.

All the women gave their informed consent to participate in the study.

In all the women a transvaginal ultrasound and a mammography were carried out. The familial history showed osteoporosis in 7 cases and breast cancer in 5 cases, with no detected cases of colon or of endometrial cancer. The personal history revealed 10 cases of uterine myomas, 2 cases of uterine polyposis (treated with operative hysteroscopy), 11 cases of breast fibromatosis, 5 cases of premenopausal polymenorrhea, and 2 cases of premature menopause.

The diet history administered by a certified nutritionist, was carried out with the aim to evaluate the dietetic behaviour of every subject. The recruited subjects did not consume soy foods and derivatives in the habitual diet and did not report dietetic habits that could negatively interfere with the phytoestrogen therapeutic response. Dietary data were collected to ascertain also the beverage intakes, including alcohol consumption. The openended interview approach has been shown to produce better estimates of energy intake at the group level than weighedfood records. In brief, the dietary interview allowed to quantify foods and drinks by a photographic food atlas (≈ 1000 photographs) of known portion sizes (40). Also the general style of life, with the frequency of physical activity and smoking habit, were recorded. Data were stored and processed using Winfood software version 2, developed by Medimatica, Milan, Italy. This database, that includes about 300 food items, made possible to calculate the daily caloric intake and the quantities of principal macro- and micro-elements (proteins, carbohydrates, lipids, calcium and vitamin D). In line with the Mediterranean Diet basic principles, all patient received dietary instruction for a diet poor in fats and proteins and rich in carbohydrates and vegetables. Women with a low calcium intake were advised to increase the consumption of milk, milk derivatives, and calciumrich mineral waters.

Treatments

All the patients received 75 mg of isoflavones once a day in the form of supplement tablets. After six months from the beginning of the treatment the subjects were recalled for a controlvisit, to revaluate the general conditions, the state of neurovegetative symptoms, the eventual side effects of the therapy on the mammary and uterine tissues, the bone mineral density (BMD), and the potential changes in their dietetic habits.

Samples collection and analytical methods

At the recruitment and after 6 months of phytoestrogenic therapy, six millilitres blood samples were collected into BD vacuteiner containing EDTA as an anticoagulant. The after supplementation drawing has been executed 8-10 hours after the ingestion of the phytoestrogenic supplement tablet, in correspondence with the highest pharmacokinetic peak of these molecules (16). Plasma samples were prepared and frozen at - 20°C until analysis. Sample preparation for plasma isoflavones analysis was performed with a modification of the method described by Manach et al. (41). To limit the isoflavones losses the plasma were acidified with 0.58 M acetic acid solution. The acidified samples were treated with enzymes, β-glucuronidase and arilsulfatase (Sigma-Aldrich), to hydrolyzed the conjugated phytoestrogens. The isoflavones extraction were performed with organic solvent (acetone) and 20 μL of clear samples were tested by HPLC.

Participants were provided supplies and instructed in the collection of a 24-hours urine sample. The collection was conducted at the recruitment and repeated after the 6 month-supplementation. In both cases the volume was recorded and two aliquots of each sample were frozen at -20°C. Sample preparation for urine isoflavones analysis was performed according to the methods described by Frankie et al. (42). 20 mL of clear urine were mixed with 0.2 M acetate buffer (pH 4) and filtered through a C18 RP-SPE column (Waters). The isoflavones were then eluted with 100% methanol. The SPE eluates were dried (by Speed Vac SC110 (Savant)), dissolved with 0.2 M phosphate buffer (pH 7) and mixed with the enzymes, β-glucuronidase and arilsulfatase (Sigma-Aldrich) to hydrolyzed the conjugated phytoestrogens. Finally an additional concentration was performed and the organic phase redissolved before the injection in the HPLC system.

The separation and determination of isoflavones by the HPLC system were obtained according to the method described by Frankie et al. (42), appropriately modified in the gradient timing. Isoflavones compounds were separated using a HPLC analytical reversed-phase column Novapak C18 (Waters, MA, USA). The optimal separation of the target molecules was obtained using a mobile phase with a three-step linear solvent gradient system, starting from 95% H2O (adjusted to pH 3.2 by H3PO4) up to 100% CH3CN during a 30 min period at a flow rate of 0.8 mL/min. UV/Vis spectra were recorded in the 190-600 nm range and the chromatograms acquired at 260 nm for genistein and at 248 nm for daidzein.

The analyses were carried out using a HPLC system from Waters Corporation equipped with a dual pump (model 515) and a supplied with a diode array detector (PDA 996) (Waters, MA, USA). The data were stored and analysed with a Waters Millennium 32 software.

The commercial formulation administered to the women were dosed with the aim to test the reliability of the isoflavonic concentration reported in the information sheet.

Results

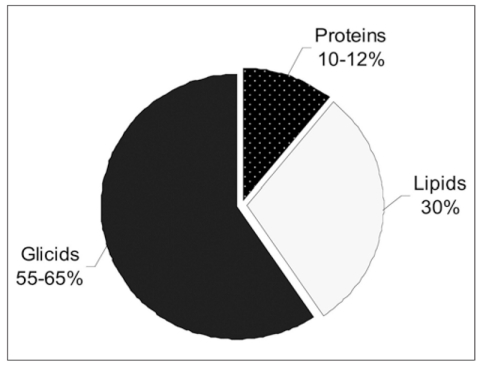

The mean Body Mass Index (BMI) of the 36 studied subjects, was 24.15 ± 3.07 kg/m2. The evaluation of the dietary composition and the dietary caloric intake of women at the recruitment and at the end of the isoflavones administration period revealed lack of differences in the diet habits. The study group showed a mean caloric intake of 1924.75 ± 197.55 Cal. The diet composition of the studied group, with a partition in carbohydrates, lipids and proteins, is shown in Figure 1. The analysis included also the percentage of animal and vegetal proteins, respectively of 63.83% ± 6.02 and 36.17 % ± 6.02. The amounts of daily mean dietary intake of calcium and of vitamin D were respectively 845.37 ± 189.38 mg and 1.76 ± 0.47 μg.

Figure 1.

Percentage of dietary components after the supplementation period.

Data about physical activity indicated that 60% of the women under study practiced a regular physical activity, intended as not less than twice a week.

Of the 36 women initially recruited, 21 completed the study, while 15 women interrupted the phytoestrogenic treatment because of either for poor compliance or for personal motivations.

The adherence to phytoestrogen therapy was excellent among completers. In women completing the six-month administration period the Greene Climateric scale value for hot flushes changed from 3 in the whole group, at the moment of the recruitment, to 1 (in 20 %) and 0 (in 80 % of cases), after 6 month-treatment (Table I). However, these results did not show any correlation with the levels of isoflavonic metabolites detected in plasma and in urines. Furthermore, no changes of the myomas, endometrial thickness, and breast tissue were detected in any of the 21 completers. Moreover, no changes in BMD were observed in the 21 completers.

Table I.

Plasmatic and urinary concentrations of isoflavones after 6 months of phytoestrogenic supplementation and entity of the symptoms before and after the supplementation.

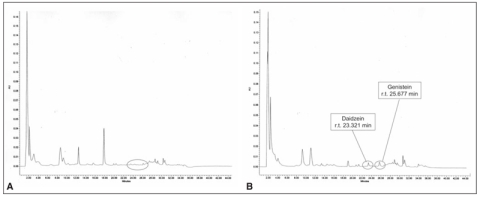

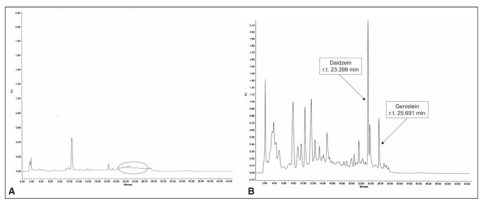

The isoflavones HPLC analyses made possible to reveal both genistein and daidzein, respectively at 260 and 248 nm in the UV-VIS spectrum. At the recruitment all patients did not present detectable concentrations of isoflavones either in plasma or urines (Figures 3a and 4a), while plasma and urines collected 8-10 hr after the ingestion of the tablet [in correspondence with the highest pharmacokinetic peak of these molecules (16)] at the end of the six-month supplementation period showed detectable amounts of genistein and daidzein (Figures 3b and 4b).

Figure 3.

Representative chromatogram of human extracted urine without (a) and with (b) phytoestrogenic supplementation.

Figure 4.

Recommended percentage of macro-elements (SINU).

In particular, after 6 months of phytoestrogenic supplementation only 19 out 21 subjects showed detectable amount of genistein in plasma, while daidzein was not detectable in any sample (Table I). Measurable levels of genistein and daidzein were observed in the urines of 17 out of the 21 cases (Table I).

The analyses conducted on the phytoestrogenic supplement tablets were carried out with the aim to validate the reliability of the isoflavonic concentration values reported by the producer.

The obtained results were compatible with the declared value for the commercial formulation (declared value 5,59 g/100g; HPLC values 5,48 g/100g).

Discussion

In the last few years the use of phytoestrogenic supplements for the treatment of menopausal symptoms has largely developed among Italian women, often in a form of “self-medication”, without any medical prescription. This study evaluated the role of phytoestrogen supplementation in the control of menopausal symptoms, using an analytical method to monitor the adsorbed orally administered isoflavones in a cohort of healthy postmenopausal women followed by a medical équipe.

The reported dietetic habits of the participants to the study showed a typical range value for age, gender and clinical status (postmenopausal women around 56 years old, with normal lipoprotein profile and no clinical complications). The group did not modify the dietetic caloric intake during the isoflavonic supplementation period, with the BMI kept constant along the observation period and in the expected range for post-menopausal women. The composition of the diet continued to show some pitfalls as the diet habits were characterized by an excessive intake in protein and fats, when compared to values recommended by the Italian Society for Human Nutrition (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Representative chromatogram of humannhydrolyzed plasma without (a) and with (b) phytoestrogenic supplementation.

Moreover, the intake of calcium and vitamin D was lower than what indicated by LARN (Recommend Daily Assumption Levels of Nutrient for the Italian Population) (43). Interestingly, as the carbohydrate ratio of the participants to this study did not exceed 49% of the entire caloric intake, they could not be ascribed to the ≥70% category, that shows an optimal isoflavones absorption (44). The rate between protein derived from animal and vegetal sources was also not ideal, being higher than recommended in the post-menopausal period (45). An excessive intake of animal proteins, favouring a low pH, causes an acceleration of bone mineral loss (46). This, together with the low intake of calcium and vitamin D for all women [average of 800 mg/day for calcium (recommended: 1200-1500 mg/die) and only 1.70 μg/day for vitamin D (recommended: 10 μg/die)], contributes to the loss of bone mineral density with increased fracture risk (47).

Under this dietary profile the results showed that the analytical method applied to evaluate phytoestrogens in biological samples was simple and efficacious. The results showed the absence of isoflavones metabolites in samples collected at the recruitment, before the starting of the supplementation, as expected in a diet lacking soy and soy-based foods (48). The plasmatic and the urinary concentrations of genistein (from 0.043 to 1.820 micromol/L; from 2.486 to 20.363 micromol/24h) and the urinary concentrations of daidzein (from 11.106 to 98.091 micromol/24h), found at the end of the six-month supplementation period, are in line with previously published data (20). In agreement with the greater bioavailability of genistein than daidzein (49), differently than in plasma, a higher daidzein excretion was registered in the urines when compared with genistein.

As published data about the true chemical composition of the commercial supplements are often discordant (50), the concentrations of the isoflavones present in the supplement tablets used in the study were analytically evaluated. The values obtained by HPLC analysis were in agreement to the declared concentrations by the producer.

The menopause is an important moment for a woman, with a number of subjects experiencing neurovegetatives symptoms, like hot flushes, with an enormous impact on their quality of life (51). Another unpleasant aspect of the menopausal transition is the development of vaginal dryness, insomnia, irritation, anxiety and in the most serious cases, depression and memory disturbances (52). The lack of the ovarian estrogen secretion promotes also a number of disorders, such as cardiovascular diseases, osteoporosis, metabolic diseases, genital prolapse and, in some cases, dementia (53).

In order to prevent these diseases, the most valid and efficacious approach is represented by HRT (54). Nowadays, HRT still represents the only recognised medical method approach to counteract menopause-linked symptoms, even though several women refuse this therapy because of growing concerns of undesirable side effects (55). Alternative therapies, whose the most popular are represented by phytoestrogens, require more research, as criticisms are frequent and several answers are still lacking. Results of clinical studies on the effects of soy product or supplement based isoflavones on vasomotor symptoms are contradictory (56, 57) However recently, some published studies showed the capability of isoflavones to reduce neurovegetative symptoms, cardiovascular diseases and osteoporosis (11, 58, 59), then the use of isoflavones could be considered for women with intense disorders.

In this studied group, the results obtained are quite encouraging for what concerns neurovegetative symptoms, such as insomnia, anxiety and mood disturbances. The most important result is the reduction in number and intensity of hot flushes, with a change of the Greene Climateric Scale value, from 3 to 1 or 0, without clinical modifications of the breast and uterine tissues. Also the observations about bone metabolism are positive, in fact the BMD of the women was maintained stable, even if a rapid worsening was expected after menopause. Our clinical observations on neurovegetative symptoms are attributable to isoflavones, the only active components of supplement administered to the patients.

In conclusion, the expected results about circulating levels of isoflavones metabolites, the dosage of the phytoestrogenic supplements and the encouraging clinical results, together with a high level of adherence to the phytoestrogenic administration in the postmenopausal women, indicate this as an effective alternative to HRT in the treatment of postmenopausal-related symptoms. Future controlled clinical trials on these “alternative remedies” would greatly contribute to confirm their long term efficacy and safety.

Acknowlegements

This work was supported by Ente Cassa di Risparmio di Firenze and CeRA (Centro Interdipartimentale di Ricerca per la valorizzazione degli Alimenti) to MLB.

References

- 1.Sirtori CR, Arnoldi A, Johnson SK. Phytoestrogens: End of a tale? Annals of Medicine. 2005;37:1–16. doi: 10.1080/07853890510044586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Manach C, Scalbert A, Morand C, et al. Polyphenols: food sources and bioavalability. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79:727–47. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.5.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.United States Department of Agriculture (USDA)-lowa State University Database on the isoflavone contents of foods (1999) Nutrient data laboratory. Available at: http://www.ars.usda.gov Accessed September 10, 2007.

- 4.Fletcher RJ. Food sources of phyto-oestrogens and their precursor in Europe. Br J Nutr. 2003;89(1):S39–S43. doi: 10.1079/BJN2002795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morandi S, D’Agostina A, Ferrario F, et al. Isoflavone content of italian soy food products and daily intakes of some specific classes of consumers. Eur Food Res Technol. 2005;221:84–91. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kloboska R, Klejdus B, Kokoska L, et al. Isoflavonoids in the solanaceae family. Polyphenols communications 2006,Winnipeg-Manitoba-Canada [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mustonen EA, Tuori M, Saastamoinen I, et al. Equol content in plasma and milk of red clover fed cows. Winnipeg-Manitoba-Canada. Polyphenols communications 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yamaguchi M. Regulatory mechanism of food factors in bone metabolism and prevention of osteoporosis. The pharmaceutical society of Japan. Yakugaku Zasshi. 2006;126(11):1117–1137. doi: 10.1248/yakushi.126.1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beck V, Rohr U, Jungbauer A. Phytoestrogens derived from red clover: An alternative to estrogen replacement therapy? J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2005;94:499–518. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2004.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Atkinson C, Frankenfeld CL, Lampe JW. Gut bacterial metabolism of the soy isoflavone Daidzein: Exploring the relevance to human health. Exp Biol Med. 2005;230:155–170. doi: 10.1177/153537020523000302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cassidy A, Albertazzi P, Nielsen IL, et al. Critical review of health effects of soyabean phyto-oestrogens in post-menopausal women. Proc Nutr Soc. 2006;65:76–92. doi: 10.1079/pns2005476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heinonen SM, Hoikkala A, Wahala K, et al. Metabolism of the soy isoflavones daidzein, genistein and glycitein in human subjects. Identification of new metabolites having an intact isoflavonoid skeleton. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2003;87(4-5):285–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2003.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.King RA, Bursill DB. Plasma urinary and kinetics of the isoflavones daidzein and genistein after a single soy meal in humans. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998;67:867–72. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/67.5.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Pasqual-Teresa S, Hallund J, Talbot D, et al. Absorption of isoflavones in humans: effects of food matrix and processing. J Nutr Biochem. J Nutr Biochem. 2006;17(4):257–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2005.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anupongsanugool E, Teekachunhatean S, Rojanasthien N, et al. Pharmacokinetics of isoflavones, daidzein and genistein, after ingestion of soy beverage compared with soy extract capsules in postmenopausal Thai women. BMC Clin Pharmacol. 2005;5(1):2. doi: 10.1186/1472-6904-5-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Setchell KD, Brown NM, Desai PB, et al. Bioavalability of pure isoflavones in healthy humans and analysis of commercial soy isoflavone supplements. J Nutr. 2001;131(4):1362S–75S. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.4.1362S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cassidy A, Brown JE, Hawdon A, et al. Factors affecting the bioavailability of soy isoflavones in humans after ingestion of physiologically relevant levels from different soy foods. J Nutr. 2006;136(1):45–51. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Setchell KDR, Brzezinski A, Brown NM, et al. Pharmacokinetics of a slow-release formulation of soybean isoflavones in healthy postmenopausal women. J Agric Food Chem. 2005;53:1938–1944. doi: 10.1021/jf0488099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bloedon Le Anne T, Robert JA, Lopaczynski W, et al. Safety and pharmacokinetics of purified soy isoflavones: single-dose administration to postmenopausal women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;76:1126–37. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/76.5.1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Setchell KDR, Faughnan MS, Avades T, et al. Comparing the pharmacokinetics of daidzein and genistein with the use of 13C-labeled tracers in premenopausal women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;77:411–9. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/77.2.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brandi ML. Natural and syntetic isoflavones in the prevention and treatment of chronic diseases. Calcif Tissue Int. 1997;61(1):S5–8. doi: 10.1007/s002239900376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anderson JJ, Garner SC. Phytoestrogens and bone. Baillieres. Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;12(4):543–57. doi: 10.1016/s0950-351x(98)80003-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kostelac D, Rechkemmer G, Briviba K. Phytoestrogens modulate binding response of estrogen receptors α and β to the estrogen response element. J Agric Food Chem. 2003;51(26):7632–7635. doi: 10.1021/jf034427b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kirk CJ, Harris RM, Wood DM, et al. Do dietary phytoestrogens influence susceptibility to hormone-dependent cancer by distrupting the metabolism of endogenous oestrogens? Biochem Soc Trans. 2001;29(Pt 2):209–16. doi: 10.1042/0300-5127:0290209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Le Bail JC, Champavier Y, Chulia AJ, et al. Effects of phytoestrogens on aromatase, 3beta and 17 beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase activities and human breast cancer cells. Life Sci. 2000;66(14):1281–91. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(00)00435-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fotsis T, Pepper MS, Montesano R, et al. Phytoestrogens and inhibition of angiogenesis. Baillieres Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;12(4):649–66. doi: 10.1016/s0950-351x(98)80009-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Traganos F, Ardelt B, Halko N, et al. Effects of genistein on the growth and cell cycle progression of normal human lymphocytes and human leukemic MOLT-4 and HL-60 cells. Cancer Res. 1992;52(22):6200–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weaver CM, Cheong JMK. Soy isoflavones and bone health: The relationship is still unclear. J Nutr. 2005;135:1243–1247. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.5.1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van Erp-Baart MA, Brants HA, Kiely M, et al. Isoflavone intake in four different European countries: the VENUS approach. Br J Nutr. 2003;89(1):S25–30. doi: 10.1079/BJN2002793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ritchie MR, Cummings JH, Morton MS, et al. A newly constructed and validated isoflavones database for the assessment of total genistein and daidzein intake. Br J Nutr. 2006;95(1):204–13. doi: 10.1079/bjn20051603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ricketts ML, Moore DD, Banz WJ, et al. Molecular mechanisms of action of the soy isoflavones includes activation of promiscuous nuclear receptors. A review. J Nutr Biochem. 2005;16(6):321–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2004.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miggiano GAD, Gagliardi L. Diet, nutrition and bone health. Clin Ter. 2005;156(1-2):47–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Potter SM, Baum JA, Teng HY, et al. Soy protein and isoflavones: their effects on blood lipids and bone density in postmenopausal women. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998;68:1375S–137S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/68.6.1375S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Setchell KDR, Lydeking-Olsen E. Dietary phytoestrogens and their effect on bone: evidence from in vitro and in vivo, human observational and dietary intervention studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;78 (suppl):593S–609S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/78.3.593S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bhakta D, Higgins CD, Sevak L, et al. Phyto-oestrogen intake and plasma concentrations in South Asian and native British women resident in England. Br J Nutr. 2006;95(6):1150–8. doi: 10.1079/bjn20061777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Berrino F. Western diet and Alzheimer’s disease. Epidemiol Prev. 2002;26(3):107–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krebs EE, Ensrud KE, MacDonald R, et al. Phytoestrogens for treatment of menopausal symptoms: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104(4):824–36. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000140688.71638.d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Greene JG. Constructing a standard climacteric scale. Maturitas. 1998;29((1)):25–31. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(98)00025-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pinkerton JV, Santen R. Use of alternatives to estrogen for treatment of menopause. Minerva. Endocrinol. 2002;27(1):21–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McGartland CP, Robson P, Murray LJ, et al. Fruit and vegetable consumption and bone mineral density: the Northern Ireland Young Hearts Project. Am J Nutr. 2004;80:1019–23. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.4.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Manach C, Morand C, Crespy V, et al. Quercetin is recovered in human plasma as conjugated derivatives which retain antioxidant properties. FEBS Lett. 1998;426(3):331–6. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00367-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Frankie AA, Custer LJ, Wang W, et al. HPLC analysis of isoflavonoids and other phenolic agents from foods and from human fluids. P.S.E.B.M. 1998;217:263–273. doi: 10.3181/00379727-217-44231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Società Italiana di Nutrizione Umana (1996) Livelli di Assunzione Raccomandati di Energia e Nutrienti per la Popolazione Italiana (LARN), S.I.N.U., Milan, Italy.

- 44.Setchell KD, Cassidy A. Dietary isoflavones: biological effects and relevance to human health. J Nutr. 1999;129(3):758S–767S. doi: 10.1093/jn/129.3.758S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sellmeyer DE, Stone KL, Sebastian A, et al. A high ratio of dietary animal to vegetable protein increases in the rate of bone loss and the risk of fracture in postmenopausal women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001;73(1):118–122. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/73.1.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Barzel US, Massey LK. Excess dietary protein can adversely affect bone. J Nutr. 1998;128:1051–1053. doi: 10.1093/jn/128.6.1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cashman KD. Diet, nutrition, and bone health. J Nutr. 2007;137(11 Suppl):2507S–2512S. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.11.2507S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.French MR, Thompson LU, Hawker GA. Validation of a phytoestrogen food frequency questionnaire with urinary concentrations of isoflavones and lignan metabolites in premenopausal women. J Am Coll Nutr. 2007;26(1):76–82. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2007.10719588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Setchell KD, Faughnan MS, Avades T, et al. Comparing the pharmacokinetics of daidzein and genistein with the use of 13C-labeled tracers in premenopausal women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;77(2):411–9. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/77.2.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Howes JB, Howes LG. Content of isoflavone-containing preparations. MJA. 2002;176(3):135–136. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2002.tb04326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wutteke W, Jarry H, Seidlova-Wuttke D. Isoflavones--safe food additives or dangerous drugs? Ageing Res Rev. 2007;6(2):150–88. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cohen LS, Soares CN, Joffe H. Diagnosis and management of mood disorders during the menopausal transition. Am J Med. 2005;118(12B):93–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.09.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Eden J. Phytoestrogens and the menopause. Baillieres. Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;12(4):581–7. doi: 10.1016/s0950-351x(98)80005-0. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sammartino A, Cirillo D, Mandato VD, et al. Osteoporosis and cardiovascular disease: benefit-risk of hormone replacement therapy. J Endocrinol Invest. 2005;28((10 Suppl)):80–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Usui T. Pharmeceutical prospects of phytoestrogens. Endocr J. 2006;53(1):7–20. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.53.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tikkanen MJ, Wahala K, Ojala S, et al. Effect of soybean phytoestrogen intake on low density lipoprotein oxidation resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95(6):3106–10. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.3106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Simons LA, Von Konigsmark M, Simons J, et al. Phytoestrogens do not influence lipoprotein levels or endothelial function in healthy, postmenopausal women. Am J Cardiol. 2000;85(11):1297–301. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(00)00759-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dixon RA. Phytoestrogens. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2004;55:225–61. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.55.031903.141729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kronenberg F, Fugh-Berman A. Complementary and alternative medicine for menopausal symptoms: a review of randomised, controlled trials. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:805–813. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-10-200211190-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]