Abstract

Integrins are heterodimeric transmembrane proteins that mediate cell-matrix interactions and modulate cell behavior. β3 subunit is a component of αII β 3 and αv β3 integrins. In this study, we first determined that β3 transcripts are expressed by cells within fracture calluses at 7 and 10 days after injury in a mouse model. We then analyzed fracture healing in mice deficient of β3 integrin with molecular, histomorphometric, and biomechanical techniques. We found that lack ofβ3 integrin results in an extended bleeding time and leads to more bone formation and accelerated cartilage maturation at 7 days after injury. However, β3 deficiency does not appear to affect later fracture healing. At days 14 and 21, histological appearance or biomechanical properties of fracture calluses are similar between wild type and mutant mice. We also found that altered fracture healing in β3 null mice is not associated with accelerated angiogenesis, since no significant difference of length density and surface density of blood vessels in fracture limbs was detected at 3 days after injury between wild type and β3 null mice. In conclusion, our findings demonstrate that β3 integrin plays an important role during early fracture healing. Further research is required to determine the underlying mechanisms.

Keywords: Beta 3 integrin, angiogenesis, fracture repair, cartilage, endochondral ossification

Introduction

Traditionally, fracture repair has been divided into four distinct phases that reflect the biological processes occurring at the site of injury. Initially, during the inflammatory stage, a hematoma forms in response to the trauma, and the inflammatory cells present in the hematoma are responsible for the first stages of healing. As skeletal progenitor cells are recruited and chondrocytes begin to differentiate, the hematoma is slowly replaced with a soft callus comprised of cartilage. After this initial stabilization, endothelial cells invade the cartilage, osteoblasts differentiate behind the invading vasculature, and a hard callus forms. The bone that forms within the fracture callus is continually remodeled by osteoclasts until the skeletal injury has been completely repaired. Thus, during fracture healing, the reparative cells have an intimate relationship with the extracellular matrices that are produced as skeletal repair proceeds.

Integrins are heterodimeric, transmembrane proteins comprised of an alpha and a beta subunit that mediate cell-matrix interactions and modulate cell behavior. At least 18 alpha subunits (α1-11, αD, E, L, M, V, X, and αII) and 8 beta subunits (β1-8) have been identified in humans and mice, and these molecules can form 24 different functional integrins (see review 1). The integrinβ3 subunit has been extensively studied. β3 subunit can combine with αII and αv subunits, forming αIIβ3 and αvβ3 intergrins respectively. αIIβ3 is expressed by platelets and mediates platelet aggregation 2; lack of β3 integrins leads to prolonged bleeding in mice due to failure to form αIIβ3 complexes 2. αvβ3 complexes are found on endothelial cells and osteoclasts and regulate blood vessel formation and bone resorption 3, 4. Mice that lack β3 integrins become osteosclerotic upon aging 5, 6, and have enhanced angiogenic properties in pathological situations 7. However, the effect that the absence of β3 integrin has on fracture healing has not been addressed.

Fracture healing is a complicated event requiring coordination of inflammation, angiogenesis, and differention of skeletogenic cells with multiple types of cells involved, such as inflammatory cells, endothelial cells, osteoblasts, chondrocytes, and osteoclasts. Thus, fundamental changes in facture repair may occur in mice that lack the β3 integrin subunit, because platelets, endothelial cells, and osteoclasts express this molecule. In this study, we examined the expression pattern ofβ3 integrin during bone repair, and we compared molecular and cellular processes during healing of non-stabilized fractures between wild type and β3– null mice. We chose to examine non-stabilized fractures, because in this model both intramembranous and endochondral ossification occur. A large callus is formed comprised of bone and cartilage, and we could assess the effect that the absence of β3 integrin has on bone healing.

Materials and Methods

Animal husbandry

All procedures were approved by the UCSF Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Wild type and β3-null mice 7 were generated using heterozygous mating pairs. Genotyping was performed at weaning by isolating DNA from the tail and performing PCR using genotype-specific primers. Only wild type and homozygous–null males were used in this study.

Cloning and determining the expression pattern of β3 integrin during bone repair

A portion of the coding region of the β3 integrin gene was cloned by PCR into pBluescript, and sequenced to confirm that the amplicon was homologous to the coding sequence of the β3 integrin gene. The plasmid was linearized and used to make radioactive antisense riboprobes (35S-UTP). Non-stabilized fractures were generated in wild type mice and animals were sacrificed at 7 and 10 days after injury. Fractured tissues were processed to paraffin sections. In situ hybridization was performed as described 8. After hybridization and washing with increasing stringency, slides were coated with liquid emulsion and were exposed for up to 2 weeks. After developing, sections were counter-stained with Hoechst dye to visualize the nuclei. Darkfield and fluorescent images were captured and superimposed in Adobe Photoshop. The darkfield image was pseudo-colored to highlight the expression pattern.

Blood counts and assay of bleeding time

Adult wild type (n=5) and β3-null mice (n=6) were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of 2% Avertin (0.015ml/g). Blood was collected by penetrating the retro-orbital plexus/sinus with a heparinized glass capillary tube and analyzed on a Beckmann Coulter Counter. The bleeding time was determined by immersing the severed tip of the tail in 0.9% saline at 37°C and counting the time required for the bleeding to cease 9.

Creating closed tibial fractures

Ten to fourteen week old wild-type or β3-null males (25–30g) were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of 2% Avertin (0.015 ml/g). A non-stabilized tibial fracture was created by three-point bending 10, and animals were allowed to ambulate freely after recovery. Buprenex (0.01mg/kg) was administered after surgery to relieve pain. Animals were sacrificed at 7, 14, and 21 days after fracture for histologic analysis (n=5/time/genotype) or at 7 days after fracture for superarray analysis (n=2/genotype).

Histologic and histomorphometric analyses of fracture healing

After euthanasia, fractured tibias were collected, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) at 4°C overnight, decalcified in 19% EDTA, dehydrated, cleared in xylene, and embedded in paraffin. Sagittal sections (10μm) through the entire callus were mounted on slides (3/slide). Depending on callus size 50–80 slides were collected. Every tenth slide was stained with safranin-O/fast green (SO/FG) to visualize cartilage 10. Adjacent slides were stained with modified Milligan’s trichrome 10, which stains bone blue. In situ hybridization was performed to assess differentiation of chondrocytes (Collagen type 2 (Col2)) and maturation of chondrocytes (Collagen type 10 (Col10)) as described above.

Histomorphometry was used to assess the volume of the callus, and the amount of cartilage and bone in each callus 10. Every thirtieth section that was stained with SO/FG or modified Milligan’s trichrome was photographed using a digital camera and a Leica DMRB microscope. Each tissue was outlined by a single investigator using the lasso tool in Adobe Photshop to outline the callus and the Magic Wand tool to select all pixels that were present in the bone or cartilage. To ensure only the tissues of interest were analyzed, both the histological appearance and the staining pattern of each tissue was used to ensure only the appropriate pixels for each tissue type were selected. Selected pixels were then saved as a separate layer in each file in order to confirm pixel selection. The number of pixels comprising callus, cartilage, or newly formed bone was determined in Adobe Photoshop 8, 10. The volume of the callus, and the volume of the cartilage and bone (Vcallus, Vcart, or Vbone) in the callus, was calculated with the following equation: Vcallus, Vcart, or . A1 and A2 are the area of the callus, cartilage, or bone in the sections that were measured, and h is the distance between A1 and A2. Student’s t-test was performed to compare Vcallus, Vcart, or Vbone at each time point between fractures in mutant and wild type animals.

Quantitative analysis of vasculature

Wild type (n=5) and β3-null adult male mice (n=6) were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of 2% Avertin. In order to isolate equivalent tissues from each sample for analysis, two insect pins were inserted into the tibia near knee joint and ankle 11mm apart. A transverse tibia fracture was then created between the two pins by three-point bending. All animals were sacrificed at 3 days after fracture and tissues between the two pins were collected, fixed in 4% PFA, decalcified in 19% EDTA at 4°C. After decalcification, tissue blocks were frozen in OCT and vertical uniform sections (10μm) were prepared through the whole tissue. To analyze blood vessels, 10–15 random sections were selected from each sample for anti-platelet cell adhesion molecule (PECAM) immunostaining 11.

Quantification of the vasculature within this tissue was performed using stereology as described 12. The early callus tissues, muscles, and other soft tissues were included in the analysis, but the bone marrow was excluded. The volume of each sample was estimated using Cavalieri’s principle 13. The length density (the length of blood vessels per unit volume of the reference space) and surface density (the area of the outer surface of blood vessels per unit volume of the reference space) of blood vessels within the tissue were estimated using an Olympus CAST system (Olympus, Center Valley, PA) and Visiopharm software (Visiopharm, Horsholm, Denmark).

Superarray Hybridization

Total RNA was extracted from fracture calluses (n=2 WT and KO) at day 7 post injury using Trizol, purified, amplified, and labeled with biotin-16-UTP (Superarray Biosciences, Frederick, MD). Each sample was hybridized to a mouse osteogenic microarray (Superarray, now SAbiosciences, Frederick, MD). After washing, hybridization signal was detected by chemiluminescence. Arrays were digitized by scanning (Epson Perfection). Data were normalized and analyzed using software provided by Superarray.

Biomechanical testing

Non-stabilized tibia fractures were created in β3-null and wild type mice and fractured tibiae were collected on 28 days after injury. Tissues were kept in PBS at −20°C until the day before testing and were thawed at 4°C overnight. Two insect pins were placed into tibia proximal and distal to the callus. Both end of the fracture tibia were mounted in PMMA. Tension testing was then performed. Two parameters were derived from tension displacement curves: failure strength, which represents the maximum tension required for failure of the callus, and stiffness, which represents slope of the load displacement curve.

Results

β3 null mice have mild anemia and prolonged bleeding time

Mice lacking the β3 integrin subunit (n=5) exhibited mild anemia. These animals had fewer red blood cells, less hemoglobin, and fewer neutrophils compared to wild type mice (Table 1). In contrast, lymphocytes and platelets were not different in β3-null mice and wild type controls. Nonetheless, bleeding time in β3-null mice was significantly prolonged. All wild type mice (n=4) stopped bleeding within 3 minutes, but bleeding in all β3 null mice (n=6) persisted beyond 10 minutes. These findings are consistent with previously published data on β3 mutant mice 9.

Table 1.

Blood counts from wild type (WT) and β3-null mice.

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) | Red blood cells (×106/μl) | Platelets (×109/μl) | White blood cells (×103/μl) | Neutrophils (×103/μl) | Lymphocytes (×103/μl) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 14.3±0.3 | 10.3±0.5 | 4.7±0.3 | 6.4±0.8 | 1.6±0.5 | 4.5±0.8 |

| β-3 null | 10.7±1.1** | 6.7±0.9** | 5.5±0.9 | 6.1±1.2 | 0.8±0.3* | 4.8±1.1 |

p<0.05 and

p<0.01 compared to wild type (WT) animals. Data are mean +/− s.d.

Expression of β3 integrin

To assess the extent to which β3 integrin could participate in fracture healing, we analyzed the expression pattern of β3 integrin in fracture calluses. At 7 and 10 days after fracture, in situ hybridization analysis revealed that β3 integrin was expressed in cells within the fracture callus (Fig. 1C, G). Cells that expressed β3 integrin were present in vascularized tissues (Fig. 1D, H).

Fig. 1.

Expression of β3 integrin in fracture calluses. (A) Safranin O/Fast Green (SO/FG) staining of a fracture callus at 7 days after injury. (B) High magnification of the box in (A) shows fibrous callus tissue. (C) Transcripts of β3 integrin (red) were detected in fibrous callus. (D) Blood vessels are detected in the fibrous callus by PECAM immunostaining. (E) Safranin O/Fast Green (SO/FG) staining of a fracture callus at 10 days after injury. (F) High magnification of the box in (E) shows fibrous callus tissue. (G) Transcripts of β3 integrin (red) were detected in (H) vascularized tissues. Scale bar: A, E = 1mm; B–D, F–H = 200 μm.

Lack of β3 integrin increases early bone formation

Next, we analyzed bone and cartilage formation at 7 days after fracture. Histomorphometric analysis showed that lack of β3 integrin significantly increased the amount of new bone within fracture calluses compared to wild type mice (Fig. 2B). This finding is further supported by our superarray analysis. Twenty three genes that were primarily related to osteogenesis were up-regulated at least 2 folds in β3 null mice compared to wild type mice (Table 2). For example, Biglycan (Bgn), collagen type 1A1 (Col1a1), collagen type 1B1 (Col1b1), and Decorin (Dcn) are important components of bone extracellular matrix and Cadherin-11 (Cdh11), Cathepsin K(Ctsk), and fibronectin 1 (Fn1) are important regulators for osteoblast function. All of these molecules were up-regulated in the mutant animals.

Fig. 2.

Histomorphometric analysis of fracture healing at 7 days after injury. (A) Total volume of callus tissue. (B) Volume of bone. (C) Volume of cartilage. β3 null mice have significantly more bone than wild type mice. Bars indicate the standard deviation.

Table 2.

Superarray analysis on gene expression in fracture calluses at 7 days after injury.

| Genes over-expressed in β3 null compared to wild type mice | Fold Change |

|---|---|

| Bgn | 5.2 |

| Bmpr2 | 3.4 |

| Cdh11 | 3.7 |

| Col11a1 | 8.8 |

| Col15a1 | 9.0 |

| Col1a1 | 6.8 |

| Col1a2 | 6.0 |

| Col2a1 | 2.6 |

| Col3a1 | 6.7 |

| Col4a1 | 2.7 |

| Col4a2 | 2.9 |

| Col5a1 | 5.1 |

| Col6a1 | 4.9 |

| Col9a3 | 6.3 |

| Csf3 | 4.0 |

| Ctsk | 4.2 |

| Dcn | 5.8 |

| Fn1 | 5.6 |

| Ibsp | 6.3 |

| Mglap | 5.0 |

| Serpinh1 | 2.8 |

| Sparc | 5.2 |

| Spp1 | 4.5 |

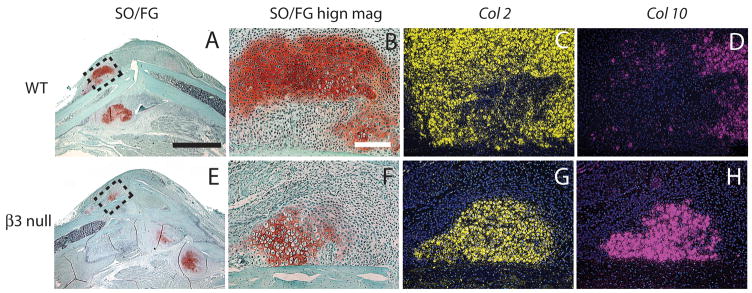

Cartilage maturation is accelerated in β3 null mice

We then assessed cartilage formation and maturation at 7 days after fracture. A similar amount of cartilage formation was observed in the wild-type and β3 null mice (Fig. 2C). Further molecular analysis of Col10 expression demonstrated that cartilage hypertrophy was more advanced in theβ3-null animals compared to the wild-type mice. In β3 integrin mutant mice, the majority of Col2 positive chondrocytes (Fig. 3G) were expressing Col10 (Fig. 3H), a marker of cartilage hypertrophy. In contrast, Col10 was detected in only a small portion of Col2 positive chondrocytes in wild-type mice (Fig. 3C, D).

Fig. 3.

Maturation of cartilage at 7 days after fracture. (A–D) wild type mice. (A) Safranin O/Fast Green staining shows cartilage formation (red) in fracture calluses. (B) High magnification of the box in (A) shows a cartilage island. (C) Transcripts of collagen type 2 (Col 2, yellow) are detected in the cartilage island. (D) Part of Col 2 domain is positive for collagen type 10 (Col 10, purple), a marker of hypertrophic chondrocytes. (E–H) β3 null mice. (E) Low and (F) high magnification of fracture callus. (G) Col 2 is expressed by chondrocytes. (H) The majority of Col 2 positive cells are expressing Col 10. Scale bar: A, E = 2mm. B–D, F–H = 100 μm.

Lack of β3 integrin does not affect late fracture healing

Our last goal was to assess later time points to determine whether the enhanced bone formation and chondrocyte hypertrophy that we observed at the early stages translated into faster or more robust fracture healing in the mutant animals. At 14 days after injury, a large amount of cartilage had been replaced by bone in both wild type and β3-null mice (Fig. 4A, C). Histomorphometric analysis revealed a similar amount of bone and cartilage within fracture calluses in both groups (Fig. 4E). By 21 days post-fracture, there was no obvious difference in the wild type and mutant mice (Fig. 4B, D, F); in both groups, the majority of cartilage had been replaced by bone and the volume of bone within fracture calluses was similar (Fig. 4B, D). Further, no significant difference of failure strength or stiffness of fracture calluses was detected between wild type and β3-null mice (Table 3).

Fig. 4.

Fracture healing at 14 and 21 days after injury. Safranin O/Fast Green staining did not reveal significant differences in fracture healing between wild type (A, B) and β3-null mice (C, D) at 14 and 21 days after injury. This is further confirmed by histomorphometric analysis (E, F). Scale bar: A–D = 2mm. Bars indicated standard deviation.

Table 3.

Tension testing on day 28 fracture calluses.

| Failure strength (N) | Stiffness (N/mm) | |

|---|---|---|

| WT | 8.48±4.50 | 52.66±22.81 |

| β3 null | 7.18±2.04 | 54.24±23.28 |

Data are mean +/− s.d.

Lack of β3 integrin does not affect early vascularization of fracture calluses

To determine the effect of lack of β3 integrin on tissue vascularization during fracture healing, vascularization of the fractured limbs was quantified using stereology at 3 days after fracture. Compared to wild type mice (n=5), β3 null mice exhibited similar length density and surface density (Table 4), suggesting that β3 integrin inactivation may not affect the formation of new blood vessels within the injured limbs during early stages of fracture healing. Thus, while the absence of β3 integrin may stimulate angiogenesis in pathological environments, we did not detect evidence that angiogenesis during fracture repair was enhanced.

Table 4.

Analysis of vasculature in fractured limbs.

| Total volume of tissue (mm3) | Length density (mm/mm3) | Surface density (mm2/mm3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 61.6±14.9 | 167.8±47.2 | 8.9±6.7 |

| β3 null | 63.6±16.6 | 180.3±92.8 | 7.2±2.0 |

Data are mean +/− s.d.

Discussion

In this current work we illustrate that β3 integrin is expressed by cells within the fracture callus, and in vivo analysis using β3 null mice demonstrated that the β3 integrin subunit is involved in the early phases of fracture healing. The absence of β3 integrin leads to more bone formation and accelerated cartilage hypertrophy at 7 days after fracture, but these changes do not persist through later stages of fracture healing (days 14 and 21). β3 deficiency could affect bone repair through multiple possible mechanisms, including malfunction of platelets, altered angiogenic response, or impaired osteoclast function. Further studies will be required to determine the exact role of integrin β3 in fracture healing.

Lack of αII β3 integrins and malfunction of platelets

β3, along with the αII subunit, forms αII β3 integrin, which is predominantly expressed on platelets mediating platelet adhesion and aggregation. Lack of β3 integrin in β3-null mice leads to the absence of αII β3, resulting in defects in platelet aggregation and prolonged bleeding time (Table 1, and also 9). After injury, coagulation problems may lead to more bleeding and the formation of a bigger hematoma at fracture site. The fracture hematoma contains a number of cytokines, such as interleukin-10 14 and vascular endothelial growth factor 15, and has pro-inflammatory 16 and pro-angiogenic 15 properties. These properties are essential for repair. Removal of the hematoma from the fracture site impairs bone healing 17. Therefore, a bigger hematoma at the fracture site could promote better healing in β3-null mice. However, some investigators have proposed that elevated levels of potsassium present in the hematoma may be cytostatic to adjacent cells 15, 18. To assess this, the effect of low molecular weight heparin derivatives on fracture healing was examined. The authors demonstrated a significant reduction in the healing capacity of fractured bones 18, but this result is not unequivocal. Using a different low molecular weight heparin derivative other investigators observed no effect on fracture healing was observed 19. Whether these results are due to the formation of a larger hematoma, or are due to a number of other potential effects on cells and proteins is unknown. A number of studies have illustrated a direct catabolic effect of heparin on bone (Reviewed in: 20). Therefore, comparing our results to these studies with anti-coagulative agents is difficult. Nonetheless, platelets are a major source of cytokines that initiate the inflammatory response after injury 21 and platelet rich plasma can enhance diabetic fracture healing 22. In our study increased bleeding could deliver more cytokines to the fracture site and lead to a net stimulation of the initial stages of repair, but this remains to be directly tested.

Lack of αvβ3 integrins and angiogenesis

αVβ3 integrins are expressed by endothelial cells and play an important role in angiogenesis. Although antagonists to αVβ3 can block angiogenesis 23, 24, mice lacking integrin β3 exhibit increased pathological angiogenesis 7 and enhanced tumor growth 25. This paradox may be partially due to the elevated expression of VEGF receptor-2 in β3 null mice 26. Based on these findings, we hypothesized that lack of β3 integrin would increase vascularization of fracture calluses. We assessed this at day 3 post-injury, a time point with abundant angiogenic response and prior to the formation of bone and cartilage. This time point allows us to eliminate sampling artifacts introduced by the presence of highly vascular bone and avascular cartilage tissues. However, we could not confirm that absence of β3 integrin favors new blood vessel formation at this early time point, suggesting either angiogenesis in fracture healing employs distinct mechanisms from tumor angiogenesis or that enhanced angiogenesis due to β3 deficiency is not robust enough to be detected.

Lack of αvβ3 integrins and osteoclast activity

Osteoclasts are responsible for bone resorption and remodeling during fracture healing. Osteoclastic activity can be detected within fracture callus through the whole repair process. In a sheep fracture model, osteoclasts are observed at 2 weeks after injury and the density of osteoclasts is increased at 6 and 9 weeks during the remodeling phase 27. Previous reports indicate that β3 integrin is essential for normal osteoclast activity. αVβ3 is expressed by osteoclasts and lack of β3 integrin in mice leads to osteosclerosis and protects animals from ovariectomy-induced bone loss 3. Due to the low resolution of in situ hybridization, in current study we were not able to provide direct evidence showing osteoclasts at fracture sites are expressing β3 integrin. However, our histomorphometric data that β3 knockout accelerates early fracture healing but exhibits no significant effects at late stages provided indirect evidence that osteoclastic remodeling could be impaired in β3 mutant mice.

In summary, we found that β3 integrin plays an important role in fracture healing. This is a promising research direction which could lead to a better understanding of bone biology and novel therapies for fracture mal-union.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by research grants from NIH-NIAMS (R01-AR053645 to T.M. and R.M.) and Synthes, Inc. (to R.M). We are grateful for the support of Gina Baldoza and Dr. Zhiqing Xing. We thank Tamara Alliston for all of her expertise. Mice lacking the β3 integrin gene were provided by Drs Richard O. Hynes and Dean Sheppard.

References

- 1.Takada Y, Ye X, Simon S. The integrins. Genome Biol. 2007;8:215. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-5-215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Quinn MJ, Byzova TV, Qin J, et al. Integrin alphaIIbbeta3 and its antagonism. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:945–52. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000066686.46338.F1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhao H, Kitaura H, Sands MS, et al. Critical role of beta3 integrin in experimental postmenopausal osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20:2116–23. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.050724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brooks PC, Clark RA, Cheresh DA. Requirement of vascular integrin alpha v beta 3 for angiogenesis. Science. 1994;264:569–71. doi: 10.1126/science.7512751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McHugh KP, Hodivala-Dilke K, Zheng M-H, et al. Mice lacking {beta}3 integrins are osteosclerotic because of dysfunctional osteoclasts. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:433–440. doi: 10.1172/JCI8905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Faccio R, Takeshita S, Zallone A, et al. c-Fms and the alphavbeta3 integrin collaborate during osteoclast differentiation. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:749–58. doi: 10.1172/JCI16924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reynolds LE, Wyder L, Lively JC, et al. Enhanced pathological angiogenesis in mice lacking beta3 integrin or beta3 and beta5 integrins. Nat Med. 2002;8:27–34. doi: 10.1038/nm0102-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chuanyong Lu, Diane TM, Ralph Hu, Marcucio S. Ischemia leads to delayed union during fracture healing: A mouse model. J Orthop Res. 2007;25:51–61. doi: 10.1002/jor.20264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hodivala-Dilke KM, McHugh KP, Tsakiris DA, et al. Beta3-integrin-deficient mice are a model for Glanzmann thrombasthenia showing placental defects and reduced survival. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:229–38. doi: 10.1172/JCI5487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lu C, Miclau T, Hu D, et al. Cellular basis for age-related changes in fracture repair. J Orthop Res. 2005;23:1300–7. doi: 10.1016/j.orthres.2005.04.003.1100230610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lu C, Marcucio R, Miclau T. Assessing angiogenesis during fracture healing. Iowa Orthop J. 2006;26:17–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lu C, Hansen E, Sapozhnikova A, et al. Effect of age on vascularization during fracture repair. J Orthop Res. 2008;26:1384–9. doi: 10.1002/jor.20667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gundersen HJ, Jensen EB. The efficiency of systematic sampling in stereology and its prediction. J Microsc. 1987;147:229–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.1987.tb02837.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hauser CJ, Joshi P, Zhou X, et al. Production of interleukin-10 in human fracture soft-tissue hematomas. Shock. 1996;6:3–6. doi: 10.1097/00024382-199607000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Street J, Winter D, Wang JH, et al. Is human fracture hematoma inherently angiogenic? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000:224–37. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200009000-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Timlin M, Toomey D, Condron C, et al. Fracture hematoma is a potent proinflammatory mediator of neutrophil function. J Trauma. 2005;58:1223–9. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000169866.88781.f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grundnes O, Reikeras O. The importance of the hematoma for fracture healing in rats. Acta Orthop Scand. 1993;64:340–2. doi: 10.3109/17453679308993640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Street JT, McGrath M, O’Regan K, et al. Thromboprophylaxis using a low molecular weight heparin delays fracture repair. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000:278–89. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200012000-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hak DJ, Stewart RL, Hazelwood SJ. Effect of low molecular weight heparin on fracture healing in a stabilized rat femur fracture model. J Orthop Res. 2006;24:645–52. doi: 10.1002/jor.20090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hirsh J, Warkentin TE, Shaughnessy SG, et al. Heparin and low-molecular-weight heparin: mechanisms of action, pharmacokinetics, dosing, monitoring, efficacy, and safety. Chest. 2001;119:64S–94S. doi: 10.1378/chest.119.1_suppl.64s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wagner DD, Burger PC. Platelets in inflammation and thrombosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:2131–7. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000095974.95122.EC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gandhi A, Doumas C, O’Connor JP, et al. The effects of local platelet rich plasma delivery on diabetic fracture healing. Bone. 2006;38:540–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brooks PC, Stromblad S, Klemke R, et al. Antiintegrin alpha v beta 3 blocks human breast cancer growth and angiogenesis in human skin. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:1815–22. doi: 10.1172/JCI118227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brooks PC, Montgomery AM, Rosenfeld M, et al. Integrin alpha v beta 3 antagonists promote tumor regression by inducing apoptosis of angiogenic blood vessels. Cell. 1994;79:1157–64. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taverna D, Moher H, Crowley D, et al. Increased primary tumor growth in mice null for beta3- or beta3/beta5-integrins or selectins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:763–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307289101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reynolds AR, Reynolds LE, Nagel TE, et al. Elevated Flk1 (vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2) signaling mediates enhanced angiogenesis in beta3-integrin-deficient mice. Cancer Res. 2004;64:8643–50. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schell H, Lienau J, Epari DR, et al. Osteoclastic activity begins early and increases over the course of bone healing. Bone. 2006;38:547–54. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]