Abstract

The C1b domain of protein kinase Cδ, a potent receptor for ligands such as diacylglycerol and phorbol esters, was synthesized by utilizing native chemical ligation. With this synthetic strategy, the domain was efficiently constructed and shown to have high affinity ligand binding and correct folding. The C1b domain has been utilized for the development of novel ligands for control of phosphorylation by PKC family members. This strategy will pave the way for the efficient construction of C1b domains modified with fluorescent dyes, biotin, etc.

Introduction

Protein kinase C (PKC) isoforms are serine/threonine protein kinases which play a pivotal role in physiological responses to growth factors, oxidative stress, and tumor promoters. These responses regulate numerous cellular processes [1,2], including proliferation [3], differentiation [4], migration [5], and apoptosis [6,7]. Under physiological conditions, signal transduction through PKC is triggered by the interaction between diacylglycerol (DAG), a lipid second messenger, and the C1 domains of PKC. The C1 domain is well conserved within the PKC superfamily, forming a zinc finger structure into which the DAG or phorbol ester inserts. Ten PKC isoforms have been described, among which PKCδ, a member of the novel PKC subfamily, is DAG/phorbol ester-dependent but calcium-insensitive. Development of ligands with high specificity for PKC isozymes has been a critical issue [8–10]. Considerable attention has been directed at development of inhibitors of PKC isoforms; however, for PKCδ, activators have a therapeutic rationale. For example, PKCδ is growth-inhibitory in NIH3T3 cells, whereas PKCα and PKCε are growth-stimulatory [10]. Thus, complementary therapeutic strategies are to inhibit a specific PKC isoform or to stimulate an antagonistic isoform. For this latter approach, activators selective for different isoforms are needed.

For the development of isozyme-specific ligands, the C1b domain provides a robust platform for binding analyses. Although bacterial expression of cloned C1b domain affords ample material, preparation of the C1b domain by synthetic methods would greatly enhance its ability to be manipulated, such as by labeling with fluorescent dyes or biotin. However, synthesis of the C1b domain by standard solid phase peptide synthesis (SPPS) is problematic on account of its size (~50 amino acids), although its synthesis by a stepwise condensation method has proven possible [11]. In this study, we applied native chemical ligation (NCL) methodology [12,13] to an efficient synthesis of the PKCδ C1b (δC1b) domain (Scheme 1).

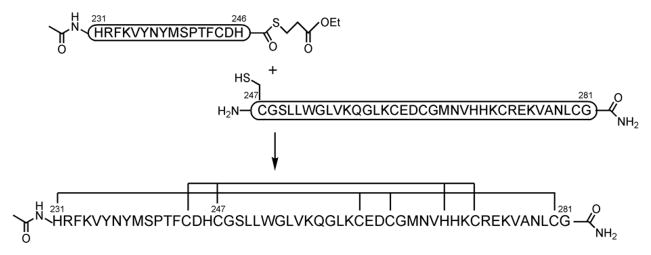

Scheme 1.

Process of native chemical ligation methodology and the sequence of synthesized δC1b domain. The amino acid residues involved in chelation of zinc ions are grouped by lines.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of amino acid-loaded 2-Chlorotrityl resin

2-Chlorotrityl chloride resin (100–200 mesh polystyrene, 1% DVB, 1.4 meq/g, 1.4 mmol) (Novabiochem) was treated with Fmoc-His(Trt)-OH (0.63 mmol) and N,N-diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA) (2.25 mmol) in dry DCM (10 mL) for 1 h. The resin was dried in vacuo after washing with dry DCM. The loading was determined by measuring UV absorption at 301 nm of the piperidine-treated Fmoc-His(Trt)-(2-Cl)Trt-resin (0.32 meq/g). Unreacted chloride was capped by treatment with MeOH (1 mL), DCM (10 mL), and DIPEA (574 μL, 3.3 mmol) for 15 min.

Synthesis of peptide thioester δC1b(231-246)

The peptide chain was manually constructed using Fmoc-based solid-phase synthesis on Fmoc-His(Trt)-(2-Cl)Trt-resin with capping (0.05 mmol scale). Fmoc-protected amino acid derivatives (5 equiv) were successively condensed using 1,3-diisopropylcarbodiimide (DIPCI) (5 equiv) in the presence of 1-hydoxybenzotriazole·H2O (HOBt·H2O) (5 equiv) in DMF (2 mL) (90 min treatment). The following side-chain protecting groups were used: Boc for Lys, Pbf for Arg, OBut for Asp, Trt for Asn, Cys, and His, But for Ser, Thr, and Tyr. The Fmoc group was deprotected with 20% piperidine in DMF (2 mL) for 15 min. After the final Fmoc deprotection, the peptide was acetylated in the mixture of Ac2O–DMF–pyridine (1:4:1, v/v, 3 mL). The yield of the resulting protected peptide resin was 335 mg. The resulting protected δC1b(231-246) was cleaved from the resin with trifluoroethanol (TFE)–AcOH–DCM (1:1:3, v/v, 15 mL) (2 h treatment), and thioesterified with ethyl mercaptopropionate (20 equiv), HOBt·H2O (10 equiv), and 1-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-3-ethylcarboiimide (EDCI)·HCl (10 equiv) in DMF (1 mL) (0°C, 2 h). Subsequently, the peptide was deprotected with trifluoroacetic acid (TFA)–thioanisole–m-cresol–triisopropylsilane (TIS) (89:7.5:2.5:1, v/v, 5 mL) (90 min treatment). After cleavage and deprotection, the crude product was precipitated and washed three times with cold diethyl ether, then purified by RP-HPLC (column: COSMOSIL 5C18 AR-II, 10 × 250 mm).

Synthesis of peptide fragment δC1b(247-281)

The peptide chain was manually constructed using Fmoc-based solid-phase synthesis on NovaSyn TGR-resin (0.26 meq/g, 0.1 mmol scale). Fmoc-protected amino acid derivatives (5 equiv) were successively condensed using DIPCI (5 equiv) in the presence of HOBt·H2O (5 equiv) in DMF (4 mL) (90 min treatment). The side-chain protecting groups were used as for the synthesis of δC1b(231-246). Additionally, Trt and OBut were used for Gln and Glu, respectively. The yield of the resulting protected peptide resin was 920 mg. Protected δC1b(247-281) was cleavaged and deprotected with TFA–thioanisole–m-cresol–TIS (89:7.5:2.5:1, v/v, 10 mL) (90 min treatment). The purificaction procedure was same as in the synthesis of δC1b(231-246).

Native chemical ligation

The thioester peptide (δC1b(231-246): 2.9 mg, 1.3 μmol), the N-terminal Cys peptide (δC1b(247-281): 4.9 mg, 1.3 μmol), and tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine hydrochloride (TCEP·HCl) (3 mg, 13 μmol) were dissolved in 1.5 mL of 6 M guanidine hydrochloride, 2 mM EDTA, and 0.1 M sodium phosphate at pH 8.5. The addition of 4% thiophenol promoted conversion of the less reactive 2-mercaptopropionate thioester to the more reactive phenyl-α-thioester and started the ligation reaction [13,14]. After incubation at 37°C under N2 atmosphere, the reaction mixture was analyzed by analytical RP-HPLC (column: COSMOSIL 5C18 AR-II, 4.6 × 250 mm, a linear gradient of 25–45% acetonitrile, 30 min). The eluent was monitored at 220 nm and characterized by ESI-MS. The product was gel filtrated with Sephadex G-10 and purified by RP-HPLC in the same condition as for peptide fragments.

ESI-MS sample preparation of the folded domain with zinc ion

The synthetic δC1b domain in ultra pure water was treated with 3 molar equivalents of ZnCl2. After incubation at 4°C for 10 min, the solution was neutralized with 10 mM of pyridinium acetate buffer (pH 6.8). The peptide concentration was adjusted to 50 μM.

Expression and purification of recombinant δC1b domain

The recombinant δC1b domain was expressed as a GST fusion domain. The protein was purified by GSTrap (GE Healthcare) following the manufacturer instruction, then the GST domain was cleaved by treatment with thrombin at 4°C for 12 h. The δC1b domain was further purified by size-exclusion chromatography. The purity of the domain was confirmed as >90% by SDS-PAGE [17].

CD spectroscopy

UV CD spectra were recorded on a Jasco J-720 spectropolarimeter at 25°C. The measurements were performed using a 0.1 cm path length cuvette at a 0.1 nm spectral resolution. Each spectrum represents the average of 10 scans, and the scan rate was 50 nm/min. The initial measurement solution contained 50 μM peptide, 50 mM Tris·HCl (pH7.5), and 1 mM DTT. ZnCl2 was added to the mixture at 100 μM. To measure the unfolded state of synthetic δC1b domain, EDTA was added to the folded peptide mixture at 100 μM.

[3H]-phorbol 12, 13-dibutylate binding

[3H]-phorbol 12, 13-dibutyrate (PDBu) binding to PKC was measured by the polyethylene glycol precipitation assay as described in [15,16] with minor modification. To determine the dissociation constant (Kd) for the synthetic δC1b, saturation curves with increasing concentrations of the [3H]PDBu were obtained in triplicate. The 250 μL of assay mixture contained 50 mM Tris·HCl (pH7.4), 1 mM ethyleneglycol-bis(β-aminoethyl)-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic Acid (EGTA), 0.1 mg/mL phosphatidylserine, 2 mg/mL bovine immunoglobulin G, variable concentrations of [3H]PDBu and nonspecific line containing the excessive amount of non-radioactive PDBu against [3H]PDBu. After the addition of peptides stored in 0.015% Triton X-100, binding was carried out at 18°C for 10 min. Samples were incubated on ice for 10 min. To precipitate peptides, 200μL of 35% polyethylene glycol in 50 mM Tris·HCl (pH7.4) was added, then vortexed, and the samples were further incubated on ice for 10min. The tubes were centrifuged at 4°C (12,200 rpm, 15 min), then 100 μl aliquot of each supernatant was transferred to scintillation vials for determination of free [3H]PDBu. Remaining supernatant was aspirated off, and the bottom of centrifuge tube was cut off just above the pellet and transferred to a scintillation vial for the determination of total bound [3H]PDBu.

Results and Discussion

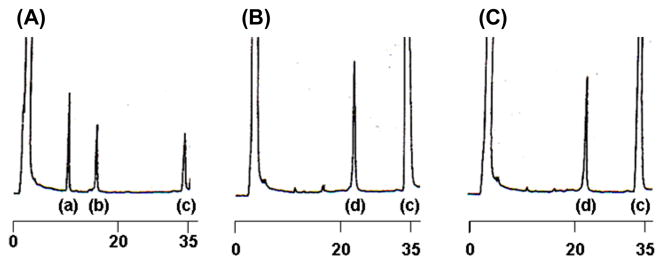

In the synthesis of the δC1b domain, the N-terminal (δC1b(231-246)) and C-terminal (δC1b(247-281)) peptide fragments were synthesized separately. In this case, an unprotected peptide δC1b(231-246) α-carboxythioester was reacted with another peptide containing an N-terminal cysteine residue, δC1b(247-281) [17]. The δC1b(231-246) and δC1b(247-281) fragment peptides were synthesized by Fmoc-based SPPS on a 2-chlorotrityl resin and on a Rink amide resin (Novasyn-TGR), respectively, as described in Materials and Methods. The fragment peptides were purified by reverse phase HPLC and characterized by electro-spray-ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (ESI-TOFMS) using a DALTONICS (BRUKER): δC1b(231-246)α-carboxythioester m/z [M+H+] calcd: 2203.5, observed: 2203.8; δC1b(247-281) m/z [M+H+] calcd: 3829.6, observed: 3829.3. The purification by HPLC (column: COSMOSIL 5C18 AR-II, 20 × 250 mm, a linear gradient of 25–30% acetonitrile in water for δC1b(231-246)α-carboxythioester and a 29% acetonitrile isocratic elution for δC1b(247-281), 30 min) gave pure fragment peptides, δC1b(231-246) α-carboxythioester and δC1b(247-281), in overall yields of 35% and 8%, respectively. The purified peptides were lyophilized and dissolved in buffer before the ligation reaction. Charts (A–C) in Figure 1 show the progress of the ligation reaction at 0, 6.5 and 18 h’s incubation, respectively. The labeled peak c shows thiophenol. The other peaks were identified by ESI-MS; a, δC1b(231-246) (2-mercaptopropionate thioester); b, δC1b(247-281); d, δC1b(231-281) m/z [M+H+] calcd: 5898.8, observed: 5899.0. Purification by reversed phase HPLC (column: COSMOSIL 5C18 AR-II, 10 × 250 mm, a linear gradient of 30–45% acetonitrile, 30 min) gave pure δC1b(231-281) in 45% overall yield. Although the δC1b domain contains six cysteine residues, the synthesis of this peptide was efficiently achieved using the ligation technique. Formerly, Futaki, et. al. [18] performed the synthesis of a Cys2His2-type zinc finger peptide by applying the native chemical ligation method. They showed that this method could apply to the synthesis of more than 90 a.a. peptide and that the synthetic peptide shows correct domain folding and zinc ion chelating as a recombinant protein. In their synthesis, the ligation junction was between methionine and cysteine at the linker residues of the zinc finger peptide. For the δC1b domain, we first attempted ligation at Phe243 and Cys244 junction because of slight possibility of epimerization in thioesterification. After confirmation of low reactivity at this junction, His246 and Cys247 junction was adopted as NCL junction. His-Cys junction has been indicated as very fast kinetics (less than 4 h to complete ligation, comparing Phe-Cys junction showed approximately 20% reaction after 48 h) residues for NCL reaction. [19]. However, the thioesterification at the C-terminal histidine residue could cause epimerization. To avoid epimerization, the reaction was performed under acidic conditions and low temperature (~0°C) [17]. After NCL reaction, the epimerization of δC1b domain was investigated by isocratic HPLC. To identify the isomer of δC1b domain, D-His incorporated fragment of δC1b(231-246) was synthesized and utilized for NCL. The retention time of D-His δC1b(231-281) was compared with those of L-His domains ligated under −20 and 0°C. The eluent peaks were identified by ESI-MS. The results indicate the synthetic δC1b(231-281) contains undetectable level of the isomer form (see Figure S1).

Figure 1.

HPLC charts of the NCL reaction solution. Charts (A)–(C) show the reaction progress at 0, 6.5, and 18 h’s incubation, respectively, after the thiophenol addition. Numbers under each chart indicate the elution time (min). Peaks (a)–(d) show as follows: a, δC1b(231-246) (2-mercaptopropionate thioester); b, δC1b(247-281); c, thiophenol; d, δC1b(231-281).

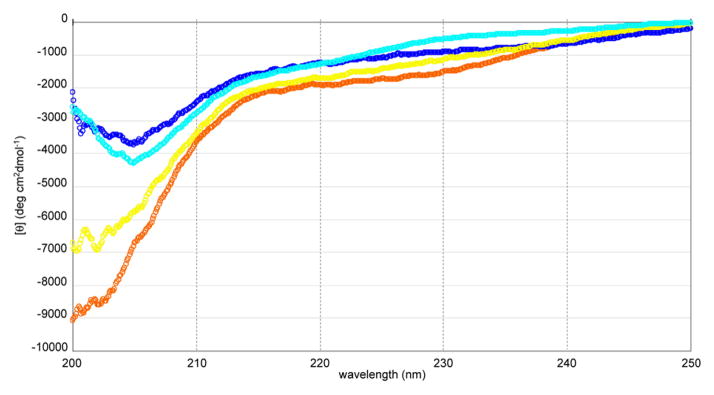

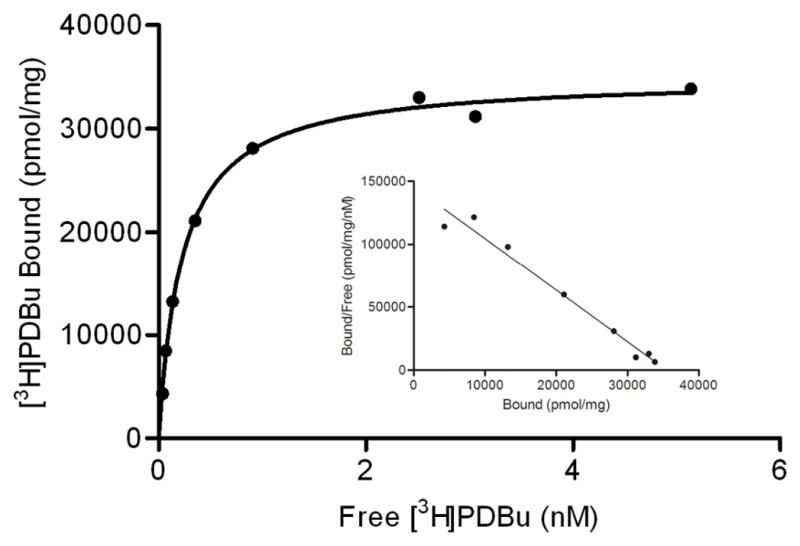

Folding properties of the peptide were assessed by circular dichroism (CD) spectra [11]. X-ray crystallography analysis of the δC1b domain has revealed that the domain is a cysteine-rich zinc finger structure with two zinc ions as cofactors [20]. Upon the addition of two molar equivalents of zinc ion to the peptide solution, a red-shift at the absorption minimum of the spectrum was observed (Figure 2). The spectrum for the folded δC1b domain was similar to that of the native δC1b domain obtained as a recombinant protein domain. The recombinant δC1b domain was expressed in E. coli and purified by GST-affinity chromatography. On the basis of the result that the recombinant domain showed equal ligand binding affinity and folding property as previously described [11], the spectrum was referred as correctly folded state of the domain. To further assess the state of folding of the synthetic δC1b domain, a molar equivalent of EDTA to zinc ion was added. The minimum absorption showed a blue-shift, indicating that the zinc ion plays an important role in the folding of the domain. Furthermore, the molecular weight of the folded domain with zinc ions was characterized by ESI-mass spectroscopy [11]. The charge states of 4+ and 5+ (m/z: 1506.6 and 1205.5, respectively) were observed and their reconstructed mass (6023.4) was consistent with the calculated mass of δC1b(231-281) + 2Zn–4H (6022.6) [21]. The ligand binding of the synthetic δC1b domain was assessed by binding assays utilizing [3H]PDBu. The Kd for PDBu was determined to be 0.34 ± 0.08 nM (mean ± SEM, n = 3 experiments) (Figure 3). This value shows that the synthetic δC1b domain is comparable to the recombinant protein domain (Kd = 0.8 ± 0.1 nM) in ligand binding analyses [22].

Figure 2.

CD spectra of the synthetic δC1b peptide in the presence or absence of metals and comparison with that of a recombinant δC1b domain. The buffer contains 50 mM Tris·HCl (pH 7.5) and 1 mM DTT. Spectra shown are as follows; orange dots, peptide (50 μM) only; blue dots, peptide (50 μM) + 100 μM ZnCl2; yellow dots, peptide (50 μM) + 100 μM ZnCl2 + 100 μM EDTA; light blue dots, the recombinant δC1b domain.

Figure 3.

Representative saturation curves with increasing concentrations of [3H]PDBu. [3H]PDBu scatchard plots for the synthetic δC1b domain are shown in the panel. Binding was measured using the polyethylene glycol precipitation assay. Each point represents the mean of triplicate determinations, generally with a standard error of 2%. Similar results were obtained in two additional experiments.

Conclusions

In summary, a Cys-rich peptide, PKCδ C1b domain, was successfully synthesized by native chemical ligation methodology. In the synthesis of C1b domains by a stepwise condensation method, special reagents and resins such as HATU and PEG-PS resin were utilized on account of difficulty in coupling [11]. The fragment condensation by NCL would be an advantageous alternative method since normal reagents can be used for the synthesis of each fragment. Proper zinc-finger structure folding was determined by CD spectra. The binding of PDBu was assessed by polyethyleneglycol precipitation assays and the result indicated that the synthetic δC1b domain is suitable for use in ligand binding analyses. This methodology makes feasible the efficient preparation of modified C1b domains, which might be useful for establishment of new binding assay methods or for characterization of newly synthetic isozyme-specific ligands.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by a Grant-in-aid from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology, Japan, and of the Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare. It was also supported in part by the Intramural Program of the National Institutes of Health, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute. The authors thank Professor Kazunari Akiyoshi, Institute of Biomaterials and Bioengineering, Tokyo Medical and Dental University, for his assistance in the circular dichroism experiments.

Footnotes

Dedicated to Dr. Victor E. Marquez on the occasion of his 65th birthday.

References

- 1.Nishizuka Y. Intracellular signaling by hydrolysis of phospholipids and activation of protein kinase C. Science. 1992;11:607–614. doi: 10.1126/science.1411571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Newton AC. Protein kinase C: structure, function, and regulation. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:28495–28498. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.48.28495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Watanabe T, Ono Y, Taniyama Y, Hazama K, Igarashi K, Ogita K, Kikkawa U, Nishizuka Y. Cell division arrest induced by phorbol ester in CHO cells overexpressing protein kinase C-delta subspecies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:10159–10163. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.21.10159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mischak H, Pierce JH, Goodnight J, Kazanietz G, Blumberg PM, Mushinski JF. Phorbol ester-induced myeloid differentiation is mediated by protein kinase C-alpha and -delta and not by protein kinase C-beta II, -epsilon, -zeta, and -eta. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:20110–20115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li C, Wernig E, Leitges M, Hu Y, Xu Q. Mechanical stress-activated PKCδ regulates smooth muscle cell migration. FASEB J. 2003;17:2106–2108. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0150fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ghayur T, Hugunin M, Talanian V, Ratnofsky S, Quinlan C, Emoto Y, Pandey P, Datta R, Huang Y, Kharbanda S, Allen H, Kamen R, Wong W, Kufe D. Proteolytic activation of protein kinase C delta by an ICE/CED 3-like protease induces characteristics of apoptosis. J Exp Med. 1996;184:2399–2404. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.6.2399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Humphries MJ, Limesand KH, Schneider JC, Nakayama KI, Anderson SM, Reyland ME. Suppression of apoptosis in the protein kinase Cδ null mouse in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:9728–9737. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507851200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tamamura H, Sigano DM, Lewin NE, Blumberg PM, Marquez VE. Conformationally constrained analogues of diacylglycerol. 20. The search for an elusive binding site on protein kinase C through relocation of the carbonyl pharmacophore along the sn-1 side chain of 1,2-diacylglycerol lactones. J Med Chem. 2004;47:644–655. doi: 10.1021/jm030454h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tamamura H, Sigano DM, Lewin NE, Peach ML, Nicklaus MC, Blumberg PM, Marquez VE. Conformationally constrained analogues of diacylglycerol (DAG). 23. Hydrophobic ligand-protein interactions versus ligand-lipid interactions of DAG-lactones with protein kinase C (PK-C) J Med Chem. 2004;47:4858–4864. doi: 10.1021/jm049723+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marquez VE, Blumberg PM. Synthetic diacylglycerols (DAG) and DAG-lactones as activators of protein kinase C (PK-C) Acc Chem Res. 2003;36:434–443. doi: 10.1021/ar020124b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Irie K, Oie K, Nakahara A, Yanai Y, Ohigashi H, Wender PA, Fukuda H, Konishi H, Kikkawa U. Molecular basis for protein kinase C isozyme-selective binding: The synthesis, folding, and phorbol ester binding of the cysteine-rich domains of all protein kinase C isozymes. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:9159–9167. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dawson PE, Muir TW, Clark-Lewis I, Kent SBH. Synthesis of proteins by native chemical ligation. Science. 1994;266:776–779. doi: 10.1126/science.7973629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dawson PE, Churchill MJ, Ghadiri MR, Kent SBH. Modulation of reactivity in native chemical ligation through the use of thiol additives. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:4325–4329. [Google Scholar]

- 14.von Eggelkraut-Gottanka R, Klose A, Beck-Sickinger AG, Beyermann M. Peptide αthioester formation using standard Fmoc-chemistry. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003;44:3551–3554. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sharkey NA, Blumberg PM. Highly lipophilic phorbol esters as inhibitors of specific [3H]phorbol 12,13-dibutyrate binding. Cancer Res. 1985;45:19–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kazanietz MG, Krausz KW, Blumberg PM. Differential irreversible insertion of protein kinase C into phospholipid vesicles by phorbol esters and related activators. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:20878–20886. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kajihara Y, Yoshihara A, Hirano K, Yamamoto N. Convenient synthesis of a sialylglycopeptide-thioester having an intact and homogeneous complex-type disialyl-oligosaccharide. Carbohydr Res. 2006;341:1333–1340. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2006.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Futaki S, Tatsuto K, Shiraishi Y, Sugiura Y. Total synthesis of artificial zinc-finger protein. Problems and perspectives. Biopolymers. 2004;76:98–109. doi: 10.1002/bip.10562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hackeng TM, Griffin JH, Dawson PE. Protein synthesis by native chemical ligation: Expanded scope by using straightforward methodology. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:10068–10073. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.18.10068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang G, Kazanietz MG, Blumberg PM, Hurley JH. Crystal structure of the cys2 activator-binding domain of protein kinase C delta in complex with phorbol ester. Cell. 1995;81:917–924. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90011-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tamamura H, Otaka T, Murakami T, Ibuka T, Sakano K, Waki M, Matsumoto A, Yamamoto N, Fujii N. An anti-HIV peptide, T22, forms a highly active complex with Zn(II) Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;229:648–652. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kazanietz MG, Wang S, Milne GW, Lewin NE, Liu LH, Blumberg PM. Residues in the second cysteine-rich region of protein kinase C δ relevant to phorbol ester binding as revealed by site-directed mutagenesis. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:21852–21859. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.37.21852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]