The prevalence of type 2 diabetes has increased in recent decades to epidemic proportions. About 150 million individuals worldwide had type 2 diabetes in 2000, and this number is expected to increase to ∼300 million by the year 2025 (1). Because of the chronic course of type 2 diabetes and the significant morbidity and mortality associated with the vascular complications of the disease, type 2 diabetes has become not only a serious public health threat, but also a heavy economic burden on the health care system. The total annual cost of diabetes care in the U.S. was estimated to be $175 billion in the year 2007, and this number is expected to increase further with the increasing incidence of the disease (2).

Recent clinical trials have reported a reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention (3,4) and pharmacotherapy (4,5) in subjects with IGT. These results suggest that primary prevention of type 2 diabetes could be an effective strategy to restrain the epidemic increase in the disease prevalence and reduce the economic burden it poses on the health care system.

Accurate identification of subjects at increased risk for future type 2 diabetes is essential for an early prevention program. It minimizes the number of subjects in the intervention program while improving the efficacy and the cost-effectiveness of the intervention. An impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) test was introduced in 1979 as an intermediate state in the transition in glucose homeostasis from normal to overt diabetes (6). Subjects with IGT have increased risk for future type 2 diabetes (7). Thus, all previous intervention trials that have tested the efficacy of prevention strategies have recruited subjects with IGT (3–5). Although, in general, subjects with IGT have an increased risk for future type 2 diabetes, only about half of IGT subjects ultimately convert to diabetes (7). On the other hand, the majority of subjects who develop type 2 diabetes do not have IGT at baseline (8). Therefore, if one relies solely on IGT to identify subjects at risk for future type 2 diabetes, a large fraction of high-risk individuals who do not have IGT and could have benefited from an intervention program would be missed.

In this review, we will examine prediction models for future risk of type 2 diabetes and demonstrate that models based on the pathophysiology of the disease have greater prediction value for the future development of type 2 diabetes.

WHO IS AT RISK FOR FUTURE TYPE 2 DIABETES?

Subjects with IGT have an increased risk for future type 2 diabetes, with a conversion rate of ∼5–10% per year (7). Although, in general, subjects with IGT have increased risk for future type 2 diabetes, only 35–50% of individuals with IGT convert to type 2 diabetes after 10–20 years of follow-up (7–9).

Prospective epidemiological studies have reported that subjects with isolated impaired fasting glucose (IFG) (fasting plasma glucose [FPG] 100–125 mg/dl and 2-h plasma glucose <140 mg/dl) also have an increased risk for future type 2 diabetes despite having a 2-h plasma glucose concentration in the normal range (10–13). The future risk for type 2 diabetes in subjects with isolated IFG is similar to that of subjects with isolated IGT (∼5% per year) (7,10–13). Most importantly, prospective epidemiological studies have demonstrated that ∼40 subjects who develop type 2 diabetes at follow-up have normal glucose tolerance (NGT) at baseline (7–13). These observations suggest that 1) the future risk for type 2 diabetes is not similar among all subjects in any glucose tolerance category and 2) a group of subjects with 2-h plasma glucose <140 mg/dl have an increased risk for future type 2 diabetes. Thus, using IGT for the prediction of future type 2 diabetes would miss this group of subjects with 2-h plasma glucose concentrations in the normal range (<140 mg/dl), yet are at increased risk for type 2 diabetes and could benefit from an intervention program.

Pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes

Subjects with type 2 diabetes have two major defects: 1) increased insulin resistance in skeletal muscle and liver and 2) impaired β-cell function (14). Both increased insulin resistance and impaired β-cell function are present long before overt hyperglycemia becomes evident. Increased insulin resistance occurs early in the natural history of type 2 diabetes but is compensated by increased β-cell secretion of insulin. When β-cell failure ensues, the hyperinsulinemia no longer can compensate for the insulin resistance and glucose homeostasis deteriorates. Initially, this is manifest as impaired glucose tolerance (IGT), which eventually progresses to overt diabetes (14). Most obese individuals are characterized by moderate-to-severe insulin resistance. However, the majority (∼70%) maintain NGT throughout life because increased insulin secretion by a healthy β-cell is able to compensate for the insulin resistance. Thus, insulin resistance alone is not sufficient for the development of type 2 diabetes, and progressive β-cell failure is required for the deterioration in glucose homeostasis and the development of hyperglycemia.

Predictors of future type 2 diabetes

Insulin resistance is prerequisite for the development of type 2 diabetes and becomes manifest long before hyperglycemia is evident. Thus, models that quantitate the severity of insulin resistance would be useful for predicting the future risk of type 2 diabetes. The euglycemic-hyperinsulinemic clamp is the gold standard for quantitation of whole-body insulin sensitivity (15). However, this technique is complicated and difficult to perform in clinical practice. Elevated fasting insulin levels, which represent the physiological response to insulin resistance, and insulin resistance indexes derived from fasting and plasma glucose and insulin concentrations during the oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) have been used to predict the future risk for type 2 diabetes (16). Subjects with insulin resistance have a cluster of metabolic abnormalities known as the insulin resistance (metabolic) syndrome (17), and a number of epidemiological studies have reported that the metabolic syndrome is a significant predictor of future type 2 diabetes (18). Linear regression models comprised of individual metabolic abnormalities associated with the insulin resistance syndrome (obesity, IFG/IGT, hypertension, and dyslipidemia), in addition to age and sex, also have been used to predict the future risk of type 2 diabetes (19–24). The predictive power of these multivariate models is comparable to that of IGT. Furthermore, addition of glucose tolerance status to the multivariate model did not improve its predictive power (19). Because all metabolic components of the multivariate model are obtained during the fasting state, these models have been proposed to replace the diagnosis of IGT in identifying subjects at increased risk for future type 2 diabetes, thereby obviating the need to perform an OGTT.

As discussed earlier, insulin-resistant individuals develop type 2 diabetes only if β-cell failure ensues. Thus, measures of β-cell function might be expected to be a key predictor for future type 2 diabetes. The hyperglycemic clamp is the gold standard method for the measurement of both first- and second-phase insulin secretion (15). Decreased first-phase insulin secretion consistently has been reported to predict the future development of type 2 diabetes (25–28). However, the hyperglycemic clamp is complicated and cannot easily be performed in clinical practice or in large-scale epidemiological studies.

Surrogate measures of β-cell function obtained from plasma glucose and insulin concentrations during the OGTT correlate well with β-cell function measured with the gold standard hyperglycemic clamp method and have been shown to be good predictors for the future risk of type 2 diabetes (29,30). A decrease in early-phase insulin secretion (ΔI0–30/ΔG0–30) during the OGTT has been shown to be a strong predictor of the future development of type 2 diabetes (16,31–33). Because of the dynamic interaction between insulin secretion and insulin resistance (34), the insulin secretion/insulin resistance index (insulin secretion rate related to the prevailing level of insulin resistance) (ΔI/ΔG ÷ IR) is a better index of β-cell function. We previously have shown that this index performs superiorly to other models in predicting the risk of future type 2 diabetes (35). Furthermore, addition of the insulin secretion/insulin resistance index to a multivariate prediction model (the San Antonio Prediction Model), which is based on measurements taken during the fasting state (e.g., FPG, HDL, blood pressure, and waist), significantly increased the predictive power of the model (35). Models based on measurements taken during the fasting state cannot incorporate any measure of β-cell function (35,36). Thus, measures of β-cell function obtained from plasma glucose and insulin concentration obtained during post–glucose load have additive information for the future risk of type 2 diabetes compared with measurements taking during the fasting state.

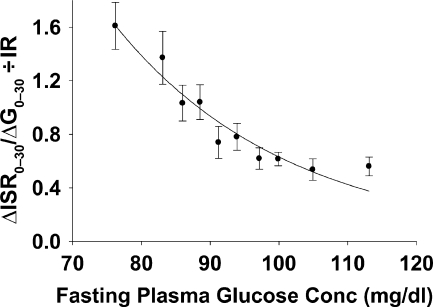

Insulin resistance, insulin secretion, and glucose intolerance

Subjects with IGT have impaired early- and late-phase insulin secretion and increased insulin resistance in skeletal muscle (37–41). These metabolic abnormalities contribute to the increased risk for future type 2 diabetes. In contrast, subjects with IFG have impaired early-phase (first-phase) insulin secretion (with normal late-phase insulin secretion) and increased hepatic insulin resistance (with normal/near-normal muscle insulin sensitivity) (37–44). It is noteworthy that the decline in β-cell function begins at 2-h plasma glucose concentrations considered to be well within the normal range (<140 mg/dl) and continuously declines as the 2-h plasma glucose rises into the impaired glucose tolerance range (45,46). Thus, subjects with a 2-h plasma glucose of 120–140 mg/dl manifest an ∼40–50% decrease in β-cell function compared with subjects with 2-h plasma glucose <100 mg/dl, yet both groups are considered to have “normal” glucose tolerance. Similarly, the decline in first-phase insulin secretion begins with FPG concentrations well within the normal range (Fig. 1) (44,47). The impairment in β-cell function associated with the deterioration in glucose tolerance represents a continuum and clearly begins at a much earlier stage than previously appreciated. By the time the plasma glucose reaches the level of IGT (2-h plasma glucose 140 mg/dl) or IFG (FPG 100 mg/dl), ∼40–50% of β-cell function has been lost (44–47). The decrease in β-cell function in subjects considered to have “normal” glucose tolerance most likely contributes to the large number of NGT subjects who convert to type 2 diabetes in prospective epidemiological studies (8). Therefore, by relying only on IFG and IGT to identify subjects at increased risk for future type 2 diabetes, those high-risk NGT subjects would not be identified. Thus, more accurate methods to predict the future risk of type 2 diabetes are required to identify this group of high-risk “normal” glucose tolerant individuals.

Figure 1.

Relationship between β-cell function and FPG concentration in subjects with NGT. Subjects were divided in deciles based on FPG concentration. Each data point is the mean of 29 subjects. The line is the least-square fit for the data points and is best described by exponential decay function [ISIR index = 32 exp(0.04FPG)] and has a correlation coefficient of r = 0.96 (P < 0.0001). Conc, concentration; G, glucose; IR, insulin resistance measured with the Matsuda index; ISR, insulin secretory rate.

Fasting versus postload plasma glucose and risk of type 2 diabetes

Both the fasting and 2-h plasma glucose concentration during the OGTT are used to establish the diagnosis of type 2 diabetes. An increase in FPG concentration in the nondiabetic range has been shown to be associated with increased risk for future type 2 diabetes (7,8,11). Subjects with isolated IFG (FPG 100–125 mg/dl and 2-h PG <140 mg/dl) have a 7.5% annual relative risk for future type 2 diabetes compared with NGT subjects (7). Moreover, the increase in future risk for type 2 diabetes associated with the increase in FPG concentration is a continuum and begins at a level below the cut point for impaired fasting glucose (100 mg/dl) (48). Similarly, an increase in 2-h plasma glucose concentration in the nondiabetic range (e.g., in subjects with IGT) also is associated with increased risk for type 2 diabetes with greater sensitivity and lower specificity compared with the increase observed with the FPG (7,8,11). However, as discussed above, both fasting and 2-h plasma glucose concentrations correlate closely with β-cell function, the principal factor responsible for the development of type 2 diabetes (35,36). First-phase insulin secretion and hepatic insulin sensitivity are important determinants of the initial rate of rise in plasma glucose concentration after glucose ingestion (49). The rate of decline in plasma glucose concentration back toward the fasting level depends on late-phase insulin secretion and insulin sensitivity in skeletal muscle (49). Thus, changes in β-cell function and insulin sensitivity will influence not only the absolute plasma glucose concentration during the fasting state and at 2 h after a glucose load, but also the shape of plasma glucose concentration curve during the OGTT: rate of plasma glucose increase, peak plasma glucose concentration, rate of plasma glucose decrease, and the time required for the plasma glucose concentration to return to the fasting level (50). Thus, the shape of the plasma glucose concentration during the OGTT provides a surrogate measure of β-cell function and whole-body insulin resistance and is a good predictor of the future risk of type 2 diabetes, above and beyond the fasting and 2-h plasma glucose concentration (50). Consistent with this concept, we have shown that the incremental area under the glucose curve during the OGTT (ΔG0–120) strongly correlates with β-cell function (35,36), and it is a strong predictor for future risk of type 2 diabetes, independent of the glucose tolerance status (35,36). Addition of ΔG(0–120) to prediction models based on measurements taken during the fasting state significantly improves their predictive power (35,36).

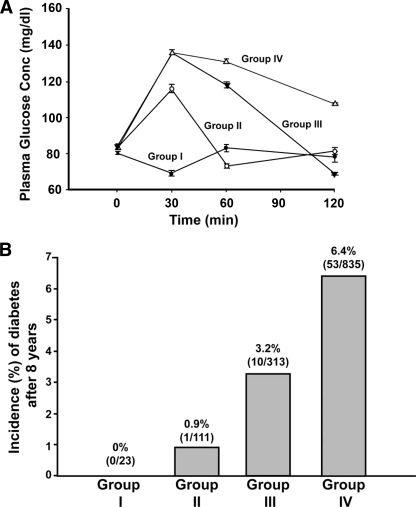

The time it takes for plasma glucose concentration to return to or below the FPG concentration during the OGTT also is an important predictor for the future development of type 2 diabetes. Normal glucose tolerant subjects who return their plasma glucose concentration back to the fasting level in <60 min during the OGTT have a significantly lower risk for future type 2 diabetes compared with subjects who require >60 min to return their plasma glucose concentration back to the fasting level (51) (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Plasma glucose concentration during the OGTT in NGT subjects. Subjects were divided into four groups (A) based on the time it takes to return their plasma glucose concentration below the fasting level. B: The 8-year conversion rate to type 2 diabetes in the four groups of subjects. See text for more details.

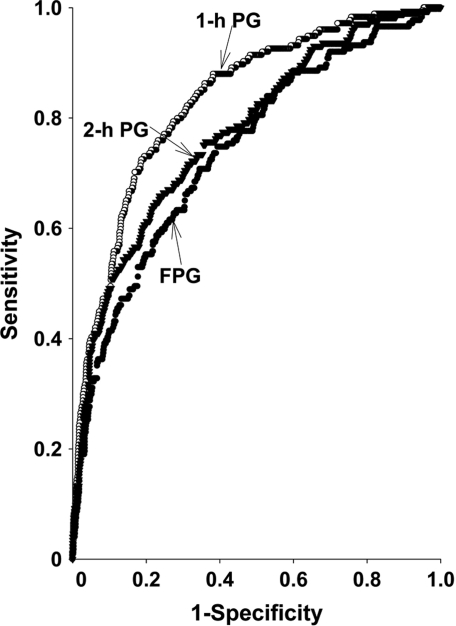

ONE-HOUR PLASMA GLUCOSE AND FUTURE RISK OF TYPE 2 DIABETES

As discussed earlier, models that include a measure of β-cell function would be expected to have a better predictor value for the future risk of type 2 diabetes. Consistent with this, we have shown that the 1-h plasma glucose concentration during the OGTT correlates better than the 2-h plasma glucose and FPG concentrations with indices of insulin secretion and insulin resistance (35,36) and with ΔG0–120, which is a strong predictor of future risk for type 2 diabetes. Thus, the 1-h plasma glucose should be a good predictor for future risk of type 2 diabetes. To our surprise, no previous epidemiological studies have assessed the predictive power of the 1-h plasma glucose concentration for future risk of type 2 diabetes. Moreover, to the best of our knowledge, the only large epidemiological studies to measure the 1-h plasma glucose concentration at baseline are the San Antonio Heart Study (35) and the Botnia Study (36). In the San Antonio Heart Study and the Botnia Study, we measured the predictive power of 1-h plasma glucose concentration using the area under the receiver-operating curve (ROC) and compared the result to area under the ROC of fasting and 2-h plasma glucose concentrations. The area under ROC for 1-h plasma glucose concentration is significantly greater compared with both the fasting and 2-h plasma glucose concentrations (Fig. 3) and to a variety of predictive models based only on measurements taken during the fasting state (Table 1) (35,36). Furthermore, addition of the 1-h plasma glucose concentration to prediction models based on measurements taken during the fasting state significantly strengthened their predictive power (35,36). A cutoff point of 155 mg/dl for 1-h plasma glucose concentration stratifies subjects into high- and low-risk groups, independent of their glucose tolerance status (36,52). Subjects with a 1-h plasma glucose ≥155 mg/dl have high risk for future diabetes, whereas subjects with a 1-h plasma glucose <155 mg/dl have low risk for future type 2 diabetes.

Figure 3.

Area under the ROC for FPG, 1-h plasma glucose (1-h PG), during OGTT, and 2-h plasma glucose concentration during the OGTT for the prediction of future type 2 diabetes in the San Antonio Heart Study (reproduced from Abdul-Ghani et al. [35]).

Table 1.

Area under the ROC for plasma glucose concentration during the OGTT and the San Antonio Diabetes Prediction Model in the San Antonio Heart Study and the Botnia Study

| Prediction model | aROC Botnia Study | aROC SAHS |

|---|---|---|

| FPG | 0.66 | 0.75 |

| SADPM | 0.75 | 0.8 |

| Plasma glucose 60 min | 0.80 | 0.84 |

| Plasma glucose 120 min | 0.69 | 0.79 |

| ΔG0–120 | 0.78 | 0.83 |

| SADPM + plasma glucose 60 min | 0.82 | 0.88 |

SADPM, San Antonio Diabetes Prediction Model. Reproduced from Abdul-Ghani et al. (37).

SUMMARY

Models that identify subjects at increased risk for future type 2 diabetes are essential for the development effective prevention programs. Progressive β-cell failure is the principal factor responsible for the development of type 2 diabetes. Although subjects with IGT are at increased risk for future type 2 diabetes, the limitations of IGT have provoked the search for more effective predictive models. A variety of multivariate models, based on measurements taken during the fasting state, have been developed. Although, in general, these models are useful tools for identifying subjects at increased risk for future type 2 diabetes, they correlate poorly with β-cell failure, the principal factor responsible for the progressive deterioration of glucose tolerance, and subsequent development of type 2 diabetes. The 1-h plasma glucose concentration during the OGTT strongly correlates with β-cell function and, as expected, performs superiorly to other models/indexes in predicting the future risk for type 2 diabetes. A 1-h cutoff point of 155 mg/dl during the OGTT stratifies individuals into high and low risk for future development of type 2 diabetes.

Acknowledgments

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Footnotes

The publication of this supplement was made possible in part by unrestricted educational grants from Eli Lilly, Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Generex Biotechnology, Hoffmann-La Roche, Johnson & Johnson, LifeScan, Medtronic, MSD, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, sanofi-aventis, and WorldWIDE.

References

- 1. King H, Aubert RE, Herman WH: Global burden of diabetes, 1995–2025: prevalence, numerical estimates, and projections. Diabetes Care 1998; 21: 1414– 1431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. American Diabetes Association Economic costs of diabetes in the US in 2007. Diabetes Care 2008; 31: 1– 20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tuomilehto J, Lindstrom J, Eriksson JG, Valle TT, Hamalainen H, Ilanne-Parikka P, Keinanen-Kiukaanniemi S, Laakso M, Louheranta A, Rastas M, Salminen V, Uusitupa M: Prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus by changes in lifestyle among subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. N Engl J Med 2001; 344: 1343– 1350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, Hamman RF, Lachin JM, Walker EA, Nathan DM: Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med 2002; 346: 393– 403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gerstein HC, Yusuf S, Bosch J, Pogue J, Sheridan P, Dinccag N, Hanefeld M, Hoogwerf B, Laakso M, Mohan V, Shaw J, Zinman B, Holman RR: Effect of rosiglitazone on the frequency of diabetes in patients with impaired glucose tolerance or impaired fasting glucose: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2006; 368: 1096– 1105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. World Health Organization. Diabetes Mellitus. Geneva, World Health Org., 1985. ( Tech. Rep. Ser., no. 727) [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gerstein HC, Santaguida P, Raina P, Morrison KM, Balion C, Hunt D, Yazdi H, Booker L: Annual incidence and relative risk of diabetes in people with various categories of dysglycemia: a systematic overview and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2007; 78: 305– 312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Unwin N, Shaw J, Zimmet P, Alberti KGMM: Impaired glucose tolerance and impaired fasting glycemia: the current status on definition and intervention. Diabet Med 2002; 19: 708– 723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dankner R, Abdul-Ghani MA, Gerber Y, Chetrit A, Wainstein J, Raz I: Predicting the 20-year diabetes incidence rate. Diabete Metab Res Rev 2007; 23: 551– 558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shaw J, Zimmet P, de Courten M, Dowse G, Chitson P, Gareeboo H, Hemraj F, Fareed D, Tuomilehto J, Alberti K: Impaired fasting glucose or impaired glucose tolerance. What best predicts future diabetes in Mauritius? Diabetes Care 1999; 22: 399– 402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gabir MM, Hanson R, Dabelea D, Imperatore G, Roumain J, Bennett P, Knowler W: Plasma glucose and prediction of microvascular disease and mortality: evaluation of 1997 American Diabetes Association and 1999 World Health Organization criteria for diagnosis of diabetes. Diabetes Care 2000; 23: 1108– 1113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. de Vegt F, Dekker JM, Stehouwer CD, Nijpels G, Bouter LM, Heine RJ: The 1997 American Diabetes Association criteria versus the 1985 World Health Organization criteria for the diagnosis of abnormal glucose tolerance: poor agreement in the Hoorn Study. Diabetes Care 1998; 21: 1686– 1690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Eschwege E, Charles MA, Simon D, Thibult N, Balkau B: Paris Prospective Study. Reproducibility of the diagnosis of diabetes over a 30-month follow-up: the Paris Prospective Study. Diabetes Care 2001; 24: 1941– 1944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. DeFronzo RA: Pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Med Clin North Am 2004; 88: 787– 835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. DeFronzo RA, Tobin JD, Andres R: Glucose clamp technique: a method for quantifying insulin secretion and resistance. Am J Physiol 1979; 237: E214– E223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hanley AJ, Williams K, Gonzalez C, D'Agostino RB, Jr, Wagenknecht LE, Stern MP, Haffner SM: San Antonio Heart Study; Mexico City Diabetes Study; Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Study. Prediction of type 2 diabetes using simple measures of insulin resistance: combined results from the San Antonio Heart Study, the Mexico City Diabetes Study, and the Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Study. Diabetes 2003; 52: 463– 469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. DeFronzo RA: Insulin resistance: a multifaceted syndrome responsible for NIDDM, obesity, hypertension, dyslipidaemia and atherosclerosis. Neth J Med 1997; 50: 191– 197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lorenzo C, Okoloise M, Williams K, Stern MP, Haffner SM: San Antonio Heart Study. The metabolic syndrome as predictor of type 2 diabetes: the San Antonio Heart Study. Diabetes Care 2003; 26: 3153– 3159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Stern MP, Williams K, Haffner SM: Identification of persons at high risk for type 2 diabetes mellitus: do we need the oral glucose tolerance test? Ann Intern Med 2002; 136: 575– 581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Aekplakorn W, Bunnag P, Woodward M, Sritara P, Cheepudomwit S, Yamwong S, Yipintsoi T, Rajatanavin R: A risk score for predicting incident diabetes in the Thai population. Diabetes Care 2006; 29: 1872– 1877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wannamethee SG, Shaper AG, Lennon L, Morris RW: Metabolic syndrome vs Framingham Risk Score for prediction of coronary heart disease, stroke, and T2DM mellitus. Arch Intern Med 2005; 165: 2644– 2650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kanaya AM, Wassel Fyr CL, de Rekeneire N, Shorr RI, Schwartz AV, Goodpaster BH, Newman AB, Harris T, Barrett-Connor E: Predicting the development of diabetes in older adults: the derivation and validation of a prediction rule. Diabetes Care 2005; 28: 404– 408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. McNeely MJ, Boyko EJ, Leonetti DL, Kahn SE, Fujimoto WY: Comparison of a clinical model, the oral glucose tolerance test, and fasting glucose for prediction of T2DM risk in Japanese Americans. Diabetes Care 2003; 26: 758– 763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lindstrom J, Tuomilehto J: The diabetes risk score: a practical tool to predict T2DM risk. Diabetes Care 2003; 26: 725– 731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. O'Rahilly SP, Nugent Z, Rudenski AS, Hosker JP, Burnett MA, Darling P, Turner RC: Beta-cell dysfunction, rather than insulin insensitivity, is the primary defect in familial type 2 diabetes. Lancet 1986; 2: 360– 364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Van Haeften TW, Dubbeldam S, Zonderland ML, Erkelens DW: Insulin secretion in normal glucose-tolerant relatives of type 2 diabetic subjects. Diabetes Care 1998; 21: 278– 282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pimenta W, Korytkowski M, Mitrakou A, Jenssen T, Yki-Jarvinen H, Evron W, Dailey G, Gerich J: Pancreatic beta-cell dysfunction as the primary genetic lesion in NIDDM. JAMA 1995; 273: 1855– 1861 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fernández-Castaner M, Biarnés J, Camps I, Ripollés J, Gómez N, Soler J: Beta-cell dysfunction in first-degree relatives of patients with non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Diabet Med 1996; 13: 953– 959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tripathy D, Almgren P, Tuomi T, Groop L: Contribution of insulin-stimulated glucose uptake and basal hepatic insulin sensitivity to surrogate measures of insulin sensitivity. Diabetes Care 2004; 27: 2204– 2210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Phillips DI, Clark PM, Hales CN, Osmond C: Understanding oral glucose tolerance: comparison of glucose or insulin measurements during the oral glucose tolerance test with specific measurements of insulin resistance and insulin secretion. Diabet Med 1994; 11: 286– 292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Haffner SM, Miettinen H, Gaskill SP, Stern MP: Decreased insulin secretion and increased insulin resistance are independently related to the 7-year risk of NIDDM in Mexican-Americans. Diabetes 1995; 44: 1386– 1391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Osei K, Rhinesmith S, Gaillard T, Schuster D: Impaired insulin sensitivity, insulin secretion, and glucose effectiveness predict future development of impaired glucose tolerance and type 2 diabetes in pre-diabetic African Americans: implications for primary diabetes prevention. Diabetes Care 2004; 27: 1439– 1446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bonora E, Kiechl S, Willeit J, Oberhollenzer F, Egger G, Meigs JB, Bonadonna RC, Muggeo M: Population-based incidence rates and risk factors for type 2 diabetes in white individuals: the Bruneck study. Diabetes 2004; 53: 1782– 1789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Diamond MP, Thornton K, Connolly-Diamond M, Sherwin RS, DeFronzo RA: Reciprocal variations in insulin-stimulated glucose uptake and pancreatic insulin secretion in women with normal glucose tolerance. J Soc Gynecol Investig 1995; 2: 708– 715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Abdul-Ghani MA, Williams K, DeFronzo RA, Stern M: What is the best predictor of future type 2 diabetes? Diabetes Care 2007; 30: 1544– 1548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Abdul-Ghani MA, Lyssenko V, Tuomi T, DeFronzo RA, Groop L: Fasting versus postload plasma glucose concentration and the risk for future type 2 diabetes: results from the Botnia Study. Diabetes Care 2009; 32: 281– 286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Abdul-Ghani MA, Tripathy D, DeFronzo RA: Contributions of beta-cell dysfunction and insulin resistance to the pathogenesis of impaired glucose tolerance and impaired fasting glucose. Diabetes Care 2006; 29: 1130– 1139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Abdul-Ghani MA, Jenkinson C, Richardson D, DeFronzo RA: Insulin secretion and insulin action in subjects with impaired fasting glucose and impaired glucose tolerance: results from the Veterans Administration Genetic Epidemiology Study (VEGAS). Diabetes 2006; 55: 1430– 1435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Meyer C, Pimenta W, Woerle HJ, Van Haeften T, Szoke E, Mitrakou A, Gerich J: Different mechanisms for impaired fasting glucose and impaired postprandial glucose tolerance in humans. Diabetes Care 2006; 29: 1909– 1914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pimenta WP, Santos ML, Cruz NS, Aragon FF, Padovani CR, Gerich JE: Brazilian individuals with impaired glucose tolerance are characterized by impaired insulin secretion. Diabete Metab 2002; 28: 468– 476 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Weyer C, Bogardus C, Pratley RE: Metabolic characteristics of individuals with impaired fasting glucose and/or impaired glucose tolerance. Diabetes 1999; 48: 2197– 2203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wasada T, Kuroki H, Katsumori K, Arii H, Sato A, Aoki K, Jimba S, Hanai G: Who are more insulin resistant, people with IFG or people with IGT? Diabetologia 2004; 47: 758– 759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Abdul-Ghani MA, Jenkinson C, Richardson D, DeFronzo RD: Impaired early but not late phase insulin secretion in subjects with impaired fasting glucose. Eur J Clin Inv. In press [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Godsland IF, Jeffs JA, Johnston DG: Loss of beta cell function as fasting glucose increases in the non-diabetic range. Diabetologia 2004; 47: 1157– 1166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Gastaldelli A, Ferrannini E, Miyazaki Y, Matsuda M, DeFronzo RA: Beta-cell dysfunction and glucose intolerance: results from the San Antonio Metabolism (SAM) study. Diabetologia 2004; 47: 31– 39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Piché M-É, Arcand-Bossé J-F, Després J-P, Pérusse L, Lemieux S, Weisnagel SJ: What is a normal glucose value? Differences in indexes of plasma glucose homeostasis in subjects with normal fasting glucose. Diabetes Care 2004; 27: 2470– 2477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Abdul-Ghani M, Matsuda M, Jani R, Jenkinson CP, Richardson DK, Kaku K, DeFronzo RA: The relationship between fasting hyperglycemia and insulin secretion in subjects with normal or impaired glucose tolerance. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2008; 295: E401– E406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Tirosh A, Shai I, Tekes-Manova D, Israeli E, Pereg D, Shochat T, Kochba I, Rudich A: Israeli Diabetes Research Group Normal fasting plasma glucose levels and type 2 diabetes in young men. N Engl J Med 2005; 353: 1454– 1462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Abdul-Ghani MA, Matsuda M, Balas B, DeFronzo RA: Muscle and liver insulin resistance indices derived from the oral glucose tolerance test. Diabetes Care 2007; 30: 89– 94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Tschritter O, Fritsche A, Shirkavand F, Machicao F, Häring H, Stumvoll M: Assessing the shape of the glucose curve during an oral glucose tolerance test. Diabetes Care 2003; 26: 1026– 1033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Abdul-Ghani MA, Williams K, DeFronzo R, Stern M: Risk of progression to T2DM based on relationship between postload plasma glucose and fasting plasma glucose. Diabetes Care 2006; 29: 1613– 1618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Abdul-Ghani MA, Abdul-Ghani TA, Ali N, DeFronzo RA: One-hour plasma glucose concentration and the metabolic syndrome identify subjects at high risk for type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2008; 31: 1650– 1655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]