Abstract

Importance of the field

Induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells offer extraordinary promise for regenerative medicine applications, and provide new opportunities for use in disease modeling, drug screening and drug toxicology.

Areas coved in this review

iPS cell technology is still in its infancy. In this review article, we present a comprehensive survey of reprogramming approaches focusing on gene-delivery systems used for generation of iPS cells from somatic cells, categorize gene-delivery vectors, and discuss their advantages and limitations for somatic cell reprogramming. We include pertinent literature published between 2006 and the present.

What the reader will gain

Although iPS cell technology has been improved via the use of various gene-delivery vectors, it still suffers from either low reprogramming efficiency or too many genomic modification steps. Extensive work is still required to improve current vectors or explore new vectors for effectively reprogramming human somatic cells into iPS cells, with or without minimal genomic modification steps.

Take home message

A single non-integrating reprogramming vector system with high reprogramming efficiency is probably essential for generation of clinically translatable human iPS cells.

Keywords: embryonic stem cells, iPS cells, pluripotent stem cells, reprogramming, iPS cells

1. Introduction

Embryonic stem cells (ES cells) are stem cells derived from the inner cell mass of an early stage embryo known as the blastocyst. These cells distinguish themselves by their unique pluripotency from multipotent progenitor cells found in the adult, and they are able to differentiate into the derivatives of the three primary germ layers: ectoderm, endoderm, and mesoderm, which include each of the more than 220 cell types in the adult body. In contrast to adult stem cells, ES cells can be propagated long-term in vitro, and they maintain pluripotency through multiple cell divisions. Mouse ES cells were first isolated by Martin Evans, Matthew Kaufman, and their colleagues in 1981 [1,2]. Eighteen years later, Thomson’s group derived human ES Cells from human blastocyst stage embryos and developed a cell culture condition for these cells [3].

Due to their plasticity and potentially unlimited capacity for self-renewal, human ES cell therapies have been proposed enthusiastically for regenerative medicine applications and tissue replacement after injury or diseases. Uses include: (1) several blood-system-related genetic diseases [4,5], (2) diabetes [6,7], (3) Parkinson's disease [8–11], (4) blindness [12], and (5) spinal cord injuries [13–17]. However, there are two major issues regarding use of human ES cells: (1) ethical concerns: the process of isolating human ES cells requires destruction of human embryos, and (2) immune rejection: the immune system of the patient recognizes cells and tissues that are not ‘self’ and accumulates a rapid response, leading to attack on the graft.

Therapeutic cloning via somatic cell nuclear transfer provides a method to generate ES cells genetically matched to diseased individuals through nuclear reprogramming of the somatic genome, technical and ethical problems are evident [18]. Consequently, alternative oocyte- and embryo-free strategies to obtain autologous pluripotent cells for transplantation therapy are being developed. An alternative approach to reprogram the somatic genome involves fusion between somatic and pluripotent ES cells [19]. Both mouse and human somatic cells can be reprogrammed by fusion to form pluripotent hybrid cells; however, the resultant hybrid cells lack therapeutic potential because of their abnormal ploidy and the presence of non-autologous genes from the pluripotent parent. Nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts from undifferentiated cells can reprogram gene expression and promote pluripotency in otherwise more developmentally restricted cell types [19,20]. Notably, extracts of embryonic carcinoma cells or ES cells elicit a shift in the transcriptional program of target cells to (1) upregulate embryonic stem cell genes, (2) downregulate somatic-cell-specific markers, and (3) epigenetically modify histones. Reprogrammed kidney epithelial cells acquire a potential for differentiation toward ectodermal and mesodermal lineages. Cell-extract-mediated nuclear reprogramming may constitute an attractive alternative to reprogramming somatic cells by cell fusion or nuclear transfer. Thus far, this approach has not been successful in reprogramming somatic cells into pluripotent stem cells with full differentiation potential.

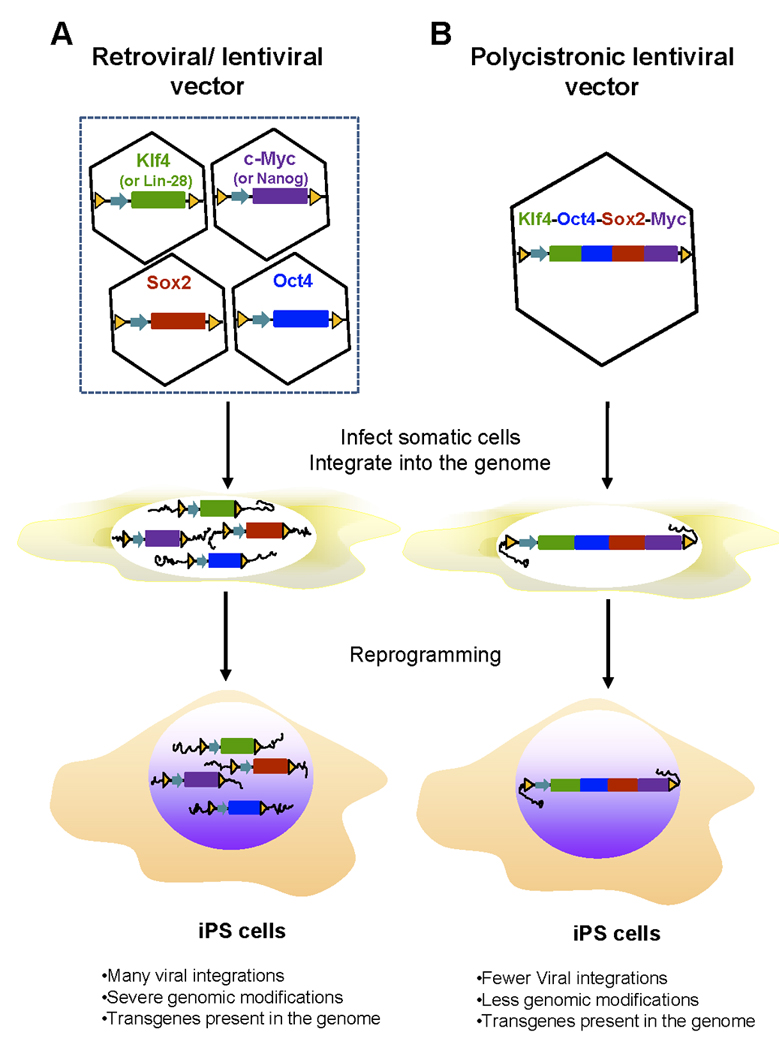

In a breakthrough study, Takahashi and Yamanaka screened a combination of 24 candidate genes and surprisingly found that viral transduction of four previously known transcription factors (Oct3/4, Sox2, Klf4 and c-Myc) can convert mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) and tail tip fibroblasts into ES cell-like cells, which are almost indistinguishable from mouse ES cells in term of pluripotency (Figure 1A). Importantly, they demonstrated the characteristics of embryonic stem cells including the ability to form chimeric mice and contribute to the germ line [21,22]. This finding was independently confirmed by the Jaenisch group [23]. This pioneering study stunned the stem cell society and attracted public attention because of the great clinical potential of these induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells. In 2007, the Yamanaka group generated human iPS cells by forced expression of the same transcription factors [24]. During that same period, the Thomson group independently succeed in reprogramming human somatic cells into iPS cells by using a slightly different combination of four factors (Oct3/4, Sox2, Nanog and Lin28) [25].

Figure 1. Retroviral and lentiviral gene delivery approach for generation of iPS cells.

A. Gene delivery of individual defined factors by retroviral and lentiviral vectors. A cocktail of retroviruses or lentiviruses expressing each of the four genes (Sox2 and Oct4 together with c-Myc and Klf4 or Lin-28 and Nanog) were infected into somatic cells. Transduced viral vectors with transgenes were randomly and stably integrated into the genomes of infected somatic cells and transmitted to iPS cells during the reprogramming. iPS cells generated by this approach are generally heavy genetically modified and harbor many copies of viral vectors and transgenes. B. Gene delivery of the four defined factors by polycistronic lentiviral vectors. Somatic cells were infected with lentiviruses carrying a fusion gene in a single open reading frame linked via the 2A viral sequences. Polycistronic lentiviral vectors were passed on to iPS cells after reprogramming. This approach created iPS cells with fewer viral integration sites and less genomic modifications.

After these pioneering demonstrations of iPS cell capacity, significant progress has been achieved and many groups have succeeded in deriving iPS cells from somatic cells by combining transcription factors and small chemical molecules [26–29]. Recently, both mouse and human iPS cells without genetic modification were generated by the protein transduction approach [30], or in combination with small chemical molecules [31]. However, these two reprogramming approaches require complicated cell culture conditions and a longer culture period [30] and suffer from low efficiency [30,31]. In addition, these approaches need either preparation of large amount of recombinant reprogramming transcription factors from bacteria, requiring high demand effort [30] or extraction of crude cell lysates from HEK 293 cells expressing defined reprogramming factors, which may be contaminated with unknown detrimental genetic materials. Thus, gene-delivery reprogramming approaches remain major strategies for generation of iPS cells for basic research.

All vector systems can be categorized by how vectors are administered to a target cell, how vectors replicate themselves, and how vectors achieve nuclear retention and stability. Vectors used widely are retroviruses, lentiviruses, adenoviruses and plasmids. A summary of current knowledge relating to delivery systems and their use follows below.

2. Integrating vectors

2.1 Delivery of reprogramming factors via retroviral vectors

Retroviral vectors are widely used gene transfer systems for both clinical gene therapy and basic research because their biology is well understood and they have high transduction efficiency. Retroviral vectors can either be replication-competent or replication-defective. Replication-competent viral vectors contain the essential genes for virion synthesis, and continue to propagate themselves once infection occurs. Because the viral genome for these vectors is large, the cloning capacity for any genes is limited. Consequently, these vectors have not been used to generate iPS cells. Conversely, replication-defective vectors are the most common choice in studies because the viruses are deleted in the coding regions for the genes necessary for additional rounds of virion replication and packaging. Viruses generated from replication-defective vectors can infect their target cells and deliver their viral payload, but avoid triggering the lytic pathway, which would result in cell lysis and death. Replication-defective viral vectors can usually hold inserts of up to 10 kb, dependent on the types of vectors.

The major drawback of the retrovirus-mediated gene delivery approach is the requirement for cells to be actively dividing for transduction to occur. As a result, slowly dividingor non-dividing cells such as neurons are very resistant to infection and transduction by retroviruses. Stable integration of retroviral DNA into the host genome leads to persistent expression of transgenes, which may lead to insertional mutagenesis and cause cancer or leukemia.

By using the retrovirus-mediated gene delivery approach (Figure 1A), Yamanaka and his colleagues for the first time delivered four reprogramming factors (Oct4, Sox2, Klf4 and c-Myc) into MEFs and mouse tail tip fibroblasts to generate iPS cells [21]. The vector used in this study is a Moloney murine leukaemia virus (MMLV)-based retrovirus vector, and the transgenes were driven by the 5′MMLV long terminal repeat (LTR) promoter, which usually is silenced in ES cells and embryonic carcinoma (EC) cells. Indeed, reprogramming factors were silenced by methylation in their generated iPS cells. However, the MMLV LTR promoter often became re-activated and drove c-Myc expression in differentiated cells derived from iPS cells subsequently causing tumor formation in iPS-cell-derived chimeric mice [32,33]. Because of this phenomena, the Yamanaka group deleted c-Myc from reprogramming factors, and unexpectedly obtained fully functional iPS cells derived from human and mouse fibroblasts by retroviral delivery [33]. Although they achieved reprogramming of human and mouse somatic cells with three transcription factors devoid of c-Myc, and the mice derived from the iPS cells were tumor free, the reprogramming efficiency was much lower than the combined four-factors process, indicating the impracticality of this approach.

To improve the efficiency, several reprogramming methods have been developed including usage of different cell types, and combination of the four defined reprogramming factors with other factors or small molecules. Additionally, the Daley group successfully isolated iPS cells from primary skin fibroblasts by retroviral transduction of the defined four factors with hTERT and SV40 large T antigen via a murine stem cell virus (MSCV) based retroviral vector, despite the low efficiency of this approach [34]. The MMLV LTR promoter is susceptible to silencing in ES cells, due to harboring several silencers such as the negative control region (NCR), direct repeat (DR) enhancer, CpG rich promoter and primer binding sites (PBS) [35]. In contrast, the MSCV LTR promoter deleted or mutated some of these silencers, and thus is more potent and able to drive expression of transgenes in ES cells [35]. However, in this study, the reprogramming factors driven by MSCV LTR were still silenced in generated human iPS cells [34], suggesting that the silencing may due to somatic cell reprogramming. Nevertheless, the MSCV-based retroviral vectors may be more effective than MMLV-based vectors in generating iPS cells, although it needs side-by-side comparison studies to compare their reprogramming efficiency.

The reprogramming efficiency of the retrovirus-mediated gene delivery approach is partially dependent on somatic cell types. Aasen et al. used human keratinocytes as a reprogrammed target cell and got 100-fold higher reprogramming efficiency than that achieved in human fibroblasts by retroviral delivery of the four defined factors [36]. Two factors (Oct4 and Klf4 or c-Myc) can convert mouse adult neural stem cells into pluripotent stem cells because of high levels of endogenous Sox2 and c-Myc [37]. Human fibroblasts can be reprogrammed into iPS cells through two reprogramming factors and small molecules, such as Oct4 and Klf4 plus BIX-01294 and Bayk8644 [26] or Oct4 and Sox2 plus VPA [28]. Similar, Giorgetti et al. generated iPS cells from human cord blood stem cells via retroviral delivery of only two reprogramming factors (Oct4 and Sox2) [38]. Interestingly, Kim et al. showed that Oct4 generates pluripotent stem cells from adult mouse neural stem cells and that the one-factor iPS cells are similar to embryonic stem cells in vitro and in vivo [39]. These approaches will make iPS cells safer and practical to use.

Significantly, the Jaenisch group reported the generation of iPS cells from sickle cell anemia by transduction of retroviruses expressing Oct4, Sox2 and Klf4 factors, and lentiviruses expressing an excisable c-Myc gene. They corrected the sickle hemoglobin allele in these anemia-specific iPS cells by gene-specific targeting and transplanted hematopoietic cells derived from these corrected iPS cells into mice with sickle cell anemia. Their data demonstrated that all systemic parameters of sickle cell anemia were improved in these animals [40]. In addition, Xu et al. showed that injection of iPS-cells-derived endothelial/endothelial progenitor cells into liver corrected the hemophilia A phenotype in mice [41]. The therapeutic potential has been demonstrated for treatment of Parkinson’s and heart diseases. The neural precursor cells derived from iPS cells were shown to improve symptoms of rats with Parkinson's disease, upon injection into the adult brain [10]. Nelson et al. showed that intramyocardial delivery of iPS yielded progenies that properly engrafted without disrupting cytoarchitecture in immunocompetent recipients. In contrast to parental nonreparative fibroblasts, iPS treatment restored postischemic contractile performance, ventricular wall thickness, and electric stability, while achieving in situ regeneration of cardiac, smooth muscle, and endothelial tissue [42]. Together, these studies demonstrated that iPS cells were inherently powerful potential tools for therapeutic application and studying treatment and mechanism of diseases.

2.2 Delivery of reprogramming factors via lentiviral vectors

Lentiviruses are a subclass of retroviruses. They can infect both dividing and non-dividing cells, and integrate into their genome, the unique feature of lentiviruses versus retroviruses, which can infect only dividing cells. Like retroviruses, the viral genome in the form of RNA is reverse-transcribed when the virus enters the cell to produce DNA, and it is passed on to the progeny of the cell when it divides.

The integration site of lentiviruses is unpredictable, which can disturb the function of cellular genes and lead to activation of oncogenes, thereby promoting tumorigenesis. However, studies have shown that lentiviral vectors have a lower predisposition to integrate in places that potentially cause cancer than gamma-retroviral vectors [43]. More specifically, one study showed that lentiviral vectors did not cause either an increase in tumor incidence or an earlier onset of tumors in mice with a much higher incidence of tumors than retroviral vectors [44]. For safety, lentiviral vectors have been produced lacking a part of the viral genome critical for their replication. Such a virus can efficiently infect cells but, once the infection has taken place, is replication-incompetent.

Initially, lentiviruses encoding Oct4, Sox2, Nanog and Lin-28 genes were used to reprogram human fibroblasts into iPS cells (Figure 1A) [25]. The reprogramming factors in this vector were driven by the EF1α promoter that is potent in ES cells. However, like the MSCV promoter, the EF1a promoter was also silenced in most human IPS cells generated in this study. By combining Oct4, Sox2, Klf4 and c-myc with SV40 large T antigen under the control of the EF1α promoter in a lentiviral system, reprogramming efficiency was enhanced up to 70-fold in human and mouse fibroblasts [45]. Zhao et al. reported that p53 siRNA and UTF1 combined with the defined four factors driven by the CMV promoter in a lentivirus vector could increase reprogramming efficiency of human iPS cell generation 100-fold [46]. Although transduction of lentivirus or retrovirus encoding defined transcriptional factors can generate human and mouse iPS cells, there is a potential disadvantage for the lentiviral reprogramming approach, that is the reprogramming factors are often reactivated when iPS cells differentiate into various lineages, thereby resulting in tumor formation. Thus, efficient and safe approaches must be developed for iPS cell generation for both basic research and future clinical applications, which induce pluripotency without transgene reactivation or even viral integration and genetic alterations.

Doxycycline-controlled lentiviral vectors with tetOP and minimal CMV promoter were recently constructed, which provide a powerful model for analyzing molecular and biochemical events accompanied epigenetic reprogramming [47,48]. According to this report, mouse iPS cells were generated after the reprogrammed factors were expressed for 10 days. During the reprogramming process, Thy1 downregulation and SSEA1 upregulation occurred first, and expression of endogenous Oct4 and Sox2 appeared much later, which means that somatic cell reprogramming into iPS cells is a gradual process. Furthermore, human secondary iPS cells were induced using lentiviral transduction [49,50], and reprogramming efficiency in secondary iPS cells is more than 100-fold (2%) higher than that found in the primary iPS cells.

Recently, we and others (Figure 1B) improved the generation of iPS cells by forced expression of four reprogramming factors from one single open reading frame (ORF) that was linked by self-cleaving 2A peptides, which are small and can efficiently self cleave at a specific site to release each factor [51–54]. This improved system not only significantly increased reprogramming efficiency (up to 100-fold) but also improved gene-silencing of transduced factors in iPS cells. These iPS cells have characteristics similar to embryonic stem cells, including gene expression and differentiation potential. Significantly, these iPS cells have a minimal number of viral integrations (one or two sites) [51], thereby decreasing the risks of gene mutagenesis and genomic instability. Importantly, this technology enables the three or four reprogramming factors to be expressed in a single vector, under the control of the CMV, EF1α or CAG promoter, thereby facilitating generation of transgene-free iPS cells.

3. Non-integrating vectors

3.1 Delivery of reprogramming factors via plasmid vectors

Reprogramming via retroviral or lentiviral infection with defined transcription factors is an inefficient process (from 0.01% to 0.1%), and requires viral transduction efficiency greater than 30% and an average of 15 different proviral copies to reprogram MEFs into iPS cells [55]. In addition, although integrated transcription factors become transcriptionally silenced over time through de novo DNA methylation, these can be spontaneously reactivated during cell culture and differentiation [32,33]. Also, viral insertions cause heavy genomic modification, such as activating or inactivating host genes, thereby leading to tumorigenicity. Thus, the problems associated with retroviral and lentiviral infection reprogramming approaches raise serious safety issues for both basic research and clinical applications.

To avoid interference with the host genome during the reprogramming process, safer methods must be developed. The transient gene expression approach is worth being explored for safe reprogramming. The Yamanaka group generated mouse iPS cells by transiently transfecting circular plasmids expressing factors into MEFs on day1, 3, 5 and 7 (Figure 2A). The established iPS cell lines are morphologically similar to mouse ES cells, and they expressed markers of ES cells at similar levels. Indeed, these iPS cells are free of vectors and integrations [56]. Similarly, Gonzalez et al. generated iPS cells from MEFs by transient transfection of a single polycistronic vector encoding four factors, and showed that these iPS cells were free of transgene integrations [57]. However, the reprogramming efficiency by plasmid transfection approach was considerably lower (1– 29 colonies from 1,000,000) than that by retroviral and lentiviral methods. There are two additional drawbacks to this approach: (1) Somatic cells reprogrammed by the plasmid transfection approach are limited by efficient transfection protocols for these cells. (2) Because transfected expression plasmids remain in cells for a few days, multiple rounds of transfection were needed for reprogramming. So far, human iPS cell lines have not been generated by this approach.

Figure 2. Generation of iPS cells via non-integrating vectors.

A. Non-episomal vectors for gene delivery of defined reprogramming factors. A mix of mammalian expression plasmid vectors for four defined factors (Oct4 and Sox2, c-Myc and Klf4) were delivered into somatic cells by multiple transfections. These vectors transiently express their encoding reprogramming factors and are gradually lost during somatic cell reprogramming and were absent from derived iPS cells. This approach could generate transgene- and vector-free iPS cells without genomic integration, but requires multiple transfection steps. Extreme low reprogramming efficiency is a major drawback of this approach. B. Episomal vectors for gene delivery of defined reprogramming factors. Somatic cells were transfected with episomal vectors carrying reprogramming factors and these vectors can replicate themselves autonomously as extra-chromosomal elements in somatic cells during reprogramming under drug selection. Episomal vectors were slowly lost during iPS cell proliferation in absence of drug selection. This approach could derive transgene- and vector-free iPS cells without the requirement for multiple transfections, but suffer from low reprogramming efficiency. C. Adenovirus gene delivery system for generation of iPS cells. A cocktail of adenovirus carrying each of the four genes (Oct4 and Sox2, c-Myc and Klf4) remained in an epichromosomal form for a few days after being infected into somatic cells and transiently expressed the encoded reprogramming factors. Adenoviral vectors were lost upon cell division and were eventually absent from derived iPS cells. Generation of iPS cells by this approach needed multiple infections and derived iPS cells were transgene- and vector-free. Reprogramming efficiency of this approach is extremely low.

3.2 Episomal plasmids

Most regular plasmid vectors lack the ability to replicate themselves in mammalian cells, leading to gradual cell division; thus, they only transiently express transgenes. However, episomal plasmid vectors, such as oriP/Epstein–Barr nuclear antigen-1 (EBNA1)-based episomal vectors replicate themselves autonomously as extrachromosomal elements without integration in both dividing and non-dividing cells [58,59]. Therefore, episomal plasmid vectors are superior to conventional plasmid vectors because of an increased expression duration of reprogramming factors in target cells. The cis-acting oriP element and the trans-acting EBNA1 protein provide sufficient support for stable extrachromosomal replication of the oriP/EBNA1-based episomal vectors. With drug selection, these vectors can be established as stable episomes in about 1% of the transfected cells [60,61] and lost at about 5% per cell division when drug selection is removed [62].

Yu et al. placed seven transcription factors in different combinations downstream of the CMV and EF1 promoters in three separate oriP/EBNA-based episomal vectors (Figure 2B) [63]. By transfecting these three episomal expression vectors into human foreskin fibroblasts, they generated functional human iPS cells and showed that vector-and transgene-free human iPS cells could be isolated through simple subcloning of iPS cell lines. However, the reprogramming efficiency of this approach as reported, was extremely low (three to six colonies per 106 input cells), which is similar to that for mouse studies based on non-integrating reprogramming approaches [56,57,64]. It is worthwhile to explore whether addition of small chemical molecules increases reprogramming efficiency by these episomal vectors. Nevertheless, this study indicated that derivation of human iPS cells does not require genomic integration or the continued expression of reprogramming factors.

3.3 Delivery of reprogramming factors via adenovirus

Similar to episomal plasmid vectors, adenoviruses are non-integrating vectors and remain epichromosomal form in all known cells except eggs. Adenoviruses can very efficiently infect virtually all cell types with the exception of some lymphoid cells, including primary replicative and non-replicative cells. By using the adenoviral delivery system, transgenes can be highly expressed with extremely low frequencies to integrate into the host genome. The drawbacks for adenoviral-mediated gene delivery are: Viruses are cleared rapidly in dividing cells and gene expression is not consistently and sufficiently long enough. It is very difficult to control gene expression level, which could become too high in infected cells if a constitutive promoter is used. These two drawbacks can be mitigated to some degree by performing multiple infections and decreasing virus load for each infection.

Stadtfeld et al. generated three iPS cells from 500,000 mouse adult hepatocytes with adenoviruses expressing c-Myc, Klf4, Oct4 and Sox2 (Figure 2C) [64]. Hepatocytes were chosen because they are highly permissive for adenoviral infection. As expected, these iPS cells were free of adenoviral vector DNA, formed teratomases when injected into the flanks of SCID mice, and generated postnatal chimeras following injection into blastocysts. Similar to the plasmid-vectors-mediated reprogramming approach, reprogramming efficiency by the adenoviral approach is also very low – only 0.0006%. Because of the low reprogramming efficiency, it is challenging to use adenoviral vectors for generating clinical useful iPS cells. Not surprisingly, the Yamanaka group failed to derive any iPS cells from mouse primary hepatocytes by introducing the four reprogramming factors with separate adenoviral vectors [56]. They suggested that this might be due to the inability to introduce the four defined factors into the same cells at sufficient levels. Recently, Zhou et al. generated iPS cells from human fibroblasts with very low reprogramming efficiency using adenoviral vectors expressing c-Myc, Klf4, Oct4 and Sox2 [65]. To ensure sufficient co-expression of the four factors in the same cells, our group tried to use adenoviruses encoding the four factors linked to a single reading frame for reprogramming. However, we were unable to generate iPS cells from MEFs. Therefore, the poor reprogramming efficiency of the adenoviral approach is unlikely to be because of its inability to deliver multiple factors into the same cells at sufficient levels. In contrast, we found that much higher gene expression was achieved by adenoviral vectors than retroviruses and lentiviruses.

Based on the studies mentioned above, adenoviral vectors have two attractive features suitable for somatic cell reprogramming: high infection efficiency for both dividing and non-dividing cells, and integration into the genome occurs rarely. However, adenoviral vectors must be improved or combined with small chemical molecules before they can be used to derive human iPS cell.

4. Excisable integrating vectors

4.1 Delivery of reprogramming factors via virus vectors with floxed transgenes

Because reprogramming efficiency by non-integrating vectors (plasmid and adenovirus) is much lower than that of retroviruses and lentiviruses, excisable integrating vectors are attractive choices for generating transgene-free iPS cells. The Jaenish group recently re-engineered lentiviral vectors that contain a Dox-inducible minimal CMV promoter for driving transgene expression and a loxP site in the 3′ LTR (Figure 3A) [66]. Upon proviral replication, the loxP site is duplicated into the 5′ LTR and results in an integrated reprogramming factor flanked with loxP sites in both LTRs. Thus, floxed reprogramming factors are excised upon Cre-recombinase expression in the cells. Using this system, they generated iPS cells from patients with Parkinson’s disease and differentiated these cells in dopaminergic neurons. Furthermore, data from the Jaenish research team indicated that transgene-free iPS cells maintain a pluripotent state and their global gene expression profiles are closer to those of human ES cells than those of human iPS cells. In this study, each of the floxed reprogramming factors was independently integrated into different sites within the genome, thus expression of Cre recombinase resulted in multiple excisions of transgenes, potentially leading to genome rearrangement and genomic instability. To avoid these drawbacks, the Townes group recently cloned a single polycistron encoding the 2A sequences linked defined reprogramming factors (driven by the elongation factor 1 alpha promoter) in a self-inactivating (SIN) lentiviral vector with a loxP site in the truncated 3′ LTR (Figure 3A). Because the defined factors were fused as a single polycistron as shown in other reports [51,52,54] in this system, upon provirus replication, the polycistron was floxed by the two loxP sites in the 5′ and 3′ LTRs, [53]. Expression of Cre recombinase in these iPS cells resulted in the excision of the integrated provirus and only 291-bp SIN LTRs containing a single loxP site remained, which did not interrupt coding sequences, promoters or regulatory elements. These factor-free iPS cells represent a more suitable source of cells for cell-based therapies or modeling of human disease. The generated iPS cell lines in this study harbored as few as three lentiviral insertions. However, these iPS cells still harbored insertion sites and thus are not ‘genetically clean’ pluripotent stem cells.

Figure 3. Derivation of iPS cells via excisable Integrating vectors.

A. Generation of transgene-free iPS cells via viral vectors with floxed transgenes. Defined reprogramming factor genes were cloned into retroviral or lentiviral vectors harboring a loxP site in the 3′ long-terminal repeat (LTR). After being transduced into somatic cells, the loxP site in the 3′ LTR is duplicated into the 5′ LTR and results in a stable integrated reprogramming factor flanked with loxP sites in both the LTRs. Integrated viral vectors could be transmitted to iPS cells during reprogramming and division. The floxed reprogramming factors integrated in the genome of iPS cells were excised upon transient expression of Cre-recombinase expression. The resultant iPS cells were transgene-free, but a LTR sequence was left behind at the same insertion site. B. piggyBac transposon gene delivery system for iPS cell generation. The fusion gene encoding four defined reprogramming factors fused via the 2A viral self-cleavable peptides was flanked with two inverted terminal repeats (ITRs) in the transposon expression vector. When this expression vector and transposase-expressing vector were transfected together into somatic cells, the transposon expression vectors expressing four defined factors were stably integrated into the genome of the cells and passed on to iPS cells after reprogramming. Upon transposase expression, transposon expression vectors were excised seamlessly from the integration sites of the genome, resulting in transgene- and vector-free iPS cells.

4.2 Delivery of reprogramming factors via piggyBac transposon/ transposase system

Transposons are mobile genetic units that can move from one position to different positions within the genome of a single cell, a process called transposition that causes mutations and genomic rearrangement in the genome. Transposons were also once called ‘jumping genes,’ and were discovered by Barbara McClintock in 1950 [67]. Based on mechanisms of their transposition, transposons can be grouped into two classes: Class I mobile genetic elements (or retrotransposons) copy themselves by first being transcribed to RNA, then reverse transcribed to DNA by reverse transcriptase, and finally are inserted at another different position in the genome. Class II mobile genetic elements move directly from one position to another using a transposase to excise themselves from their original location and insert themselves into a new locus within the genome, a process called ‘cut and paste’. Transposons are very useful tools to deliver exogenous DNA into or alter DNA inside cells of living organisms, which include different species from insect to mammalian cells.

The piggyBac (PB) transposon belongs to the class II mobile genetic element and requires only the 13 bp inverted terminal repeats (ITR) and active transposase enzyme (594 amino acids) to catalyze insertion or excision, or both [68,69]. Thus, it is possible that class II transposons are cut without inserting into another position, thus resulting in seamless excision, upon local availability or enzymatic activity of transposase, or both. These unique features make piggyBac transposon/transposase system one of best choices for delivering reprogramming factors into somatic cells to generate ‘genetically clean’ iPS cells.

Recently, two research teams highly efficiently generated iPS cells using the piggyBac transposon/transposase system to deliver a single polycistron encoding four reprogramming factors linked by the viral 2A self-cleavable peptides [51–54] into somatic cells (Figure 3B) [70,71]. By ectopic expression of transposase in established iPS cell lines, authors demonstrated the traceless elimination of reprogramming factors and seamless excision of individual PB transposon insertions. Transposon-based reprogramming of somatic cells into iPS cells has the following major advantages: PB transposition is technically simpler than other gene-delivery approaches, requiring simple plasmid DNA preparation and eliminating the need for virus production. A broad range of somatic cells are susceptible to PB transposition. More significantly transgenes and PB transposon insertions can be removed seamlessly from the genome, thus decreasing genomic modifications in established iPS cell lines. However, transposon-based reprogramming is dependent on commercial transfection reagents or methods for DNA delivery into somatic cells, which could become an impediment for some primary cells due to their resistance to DNA transfection. In addition, although integrated PB transposon vectors (and transgenes) can be tracelessly removed from the genome, transposition is not always precise. For example, Wang et al. found alterations in 5% of the transpositions [72]. Thus, consecutive transposition events into unknown sites before final elimination could cause footprints in generated human iPS cell genome. In addition, repeated transposition may cause gene duplication in cells [73]. So far, this system has been only moderately efficient in generation of iPS cells only from murine and human embryonic fibroblasts [70,71] and the feasibility use of PS transposons for reprogramming hard-to-reprogram cells such as adult dermal fibroblasts is still to be demonstrated.

5. Expert opinion and conclusions

Somatic cell reprogramming was originally achieved by gene-delivery systems via integrating viruses. Now, it is possible to derive both mouse and human iPS cells from somatic cells by the protein transduction approach, but reprogramming efficiency is excessively low to be practical for clinical and research applications [74]. Therefore, gene-delivery reprogramming approaches will remain major choices for reprogramming studies. Transgene- and vector-free iPS cells have been generated by the PB transposon/transposase system and episomal plasmid vectors. The reprogramming efficiency of the PB transposition approach is fairly efficient. But, there are two drawbacks that need to be addressed: (1) delivery of PB plasmid vectors into cells is dependent on transfection reagents, (2) PB insertion sites in each cell are uncontrolled. Episomal vector reprogramming approaches are in principle superior to other genetic reprogramming approaches. However, reprogramming efficiency needs to be further improved, for example, by combining with various small chemical molecules that can enhance reprogramming efficiency. Similar to PB transposition approaches, delivery of episomal vectors into cells could be a problem for primary somatic cells. This problem might be solved by using adenovirus–episomal vector hybrid systems [75] that utilize Cre-mediated, site-specific recombination to excise an episomal vector from a target recombinant adenovirus genome. In addition, other gene-delivery approaches, such as the adeno-associated virus (AAV) delivery system, should be exploited to generate iPS cells in the future. The AAV has several unique features: (1) apparent lack of pathogenicity, (2) the capability to infect dividing and non-dividing cells, and (3) the ability to stably integrate into the host cell genome at a specific site (designated AAVS1) in human chromosome 19. If combined with the LoxP/Cre system and the expression cassette expressing defined reprogramming factors in a single ORF [51–54], AAV could generate transgene-free human iPS cells through site-specific integration and excision of transgenes. In addition, recent studies demonstrated that the Ink4/Arf and p53-p21 pathway serve a barrier in iPS cell generation [76–81]. Thus, in the future years, it will be worthwhile to test whether the combination of transient p53 inhibition and delivery of reprogramming factors via non-integrating vectors could generate genetic-modification-free human iPS cells with a higher reprogramming efficiency.

Article highlights

Introduction. Gene-delivery reprogramming approaches remain major strategies for generation of iPS cells for basic research. We classified reprogramming vectors into three major categories: (1) integrating vectors, (2) non-integrating vectors, and (3) excisable integrating vectors.

Integrating vectors. Retrovirus and lentivirus are integrating vectors, and they are most commonly used in somatic cell reprogramming. iPS cells created by these vectors are genetically modified by viral insertions.

Non-integrating vectors. This category includes conventional plasmid expression vectors, episomal plasmid expression vectors and adenovirus. These vectors can generate iPS cells without vector integration, but reprogramming efficiency is very low.

Excisable integrating vectors. Retroviral or lentiviral vectors with floxed transgenes and piggyBac transposon vector belong to this category, and they can generate transgene-free and genomic-modification-free iPS cells, respectively.

Acknowledgments

We thank our colleagues at Maine Medical Center Research Institute (MMCRI) for their critical review.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

This work was supported by NIH grant (1R21HD061777) from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development. W.S.W was supported by a K01 award from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease (K01DK078180).

Bibliography

- 1.Evans MJ, Kaufman MH. Establishment in culture of pluripotential cells from mouse embryos. Nature. 1981;292(5819):154–156. doi: 10.1038/292154a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martin GR. Isolation of a pluripotent cell line from early mouse embryos cultured in medium conditioned by teratocarcinoma stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1981;78(12):7634–7638. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.12.7634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thomson JA, Itskovitz-Eldor J, Shapiro SS, et al. Embryonic stem cell lines derived from human blastocysts. Science. 1998;282(5391):1145–1147. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5391.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blau CA. Current status of stem cell therapy and prospects for gene therapy for the disorders of globin synthesis. Baillieres Clin Haematol. 1998;11(1):257–275. doi: 10.1016/s0950-3536(98)80078-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moayeri M, Hawley TS, Hawley RG. Correction of murine hemophilia a by hematopoietic stem cell gene therapy. Mol Ther. 2005;12(6):1034–1042. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burns CJ, Persaud SJ, Jones PM. Diabetes mellitus: A potential target for stem cell therapy. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther. 2006;1(2):255–266. doi: 10.2174/157488806776956832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamaoka T. Regeneration therapy for diabetes mellitus. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2003;3(3):425–433. doi: 10.1517/14712598.3.3.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim JH, Auerbach JM, Rodriguez-Gomez JA, et al. Dopamine neurons derived from embryonic stem cells function in an animal model of Parkinson's disease. Nature. 2002;418(6893):50–56. doi: 10.1038/nature00900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ho HY, Li M. Potential application of embryonic stem cells in Parkinson's disease: Drug screening and cell therapy. Regen Med. 2006;1(2):175–182. doi: 10.2217/17460751.1.2.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wernig M, Zhao JP, Pruszak J, et al. Neurons derived from reprogrammed fibroblasts functionally integrate into the fetal brain and improve symptoms of rats with parkinson's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(15):5856–5861. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801677105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muramatsu S, Okuno T, Suzuki Y, et al. Multitracer assessment of dopamine function after transplantation of embryonic stem cell-derived neural stem cells in a primate model of parkinson's disease. Synapse. 2009;63(7):541–548. doi: 10.1002/syn.20634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cicero SA, Johnson D, Reyntjens S, et al. Cells previously identified as retinal stem cells are pigmented ciliary epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(16):6685–6690. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901596106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matsuda R, Yoshikawa M, Kimura H, et al. Cotransplantation of mouse embryonic stem cells and bone marrow stromal cells following spinal cord injury suppresses tumor development. Cell Transplant. 2009;18(1):39–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Enzmann GU, Benton RL, Talbott JF, et al. Functional considerations of stem cell transplantation therapy for spinal cord repair. J Neurotrauma. 2006;23(3–4):479–495. doi: 10.1089/neu.2006.23.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hendricks WA, Pak ES, Owensby JP, et al. Predifferentiated embryonic stem cells prevent chronic pain behaviors and restore sensory function following spinal cord injury in mice. Mol Med. 2006;12(1–3):34–46. doi: 10.2119/2006-00014.Hendricks. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McDonald JW, Becker D, Holekamp TF, et al. Repair of the injured spinal cord and the potential of embryonic stem cell transplantation. J Neurotrauma. 2004;21(4):383–393. doi: 10.1089/089771504323004539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kimura H, Yoshikawa M, Matsuda R, et al. Transplantation of embryonic stem cell-derived neural stem cells for spinal cord injury in adult mice. Neurol Res. 2005;27(8):812–819. doi: 10.1179/016164105X63629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Markoulaki S, Meissner A, Jaenisch R. Somatic cell nuclear transfer and derivation of embryonic stem cells in the mouse. Methods. 2008;45(2):101–114. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Byrne JA. Generation of isogenic pluripotent stem cells. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17(R1):R37–R41. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Collas P, Taranger CK. Epigenetic reprogramming of nuclei using cell extracts. Stem Cell Rev. 2006;2(4):309–317. doi: 10.1007/BF02698058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126(4):663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okita K, Ichisaka T, Yamanaka S. Generation of germline-competent induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2007;448(7151):313–317. doi: 10.1038/nature05934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wernig M, Meissner A, Foreman R, et al. In vitro reprogramming of fibroblasts into a pluripotent ES-cell-like state. Nature. 2007;448(7151):318–324. doi: 10.1038/nature05944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, et al. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 2007;131(5):861–872. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu J, Vodyanik MA, Smuga-Otto K, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells. Science. 2007;318(5858):1917–1920. doi: 10.1126/science.1151526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shi Y, Desponts C, Do JT, et al. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic fibroblasts by Oct4 and Klf4 with small-molecule compounds. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3(5):568–574. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shi Y, Do JT, Desponts C, et al. A combined chemical and genetic approach for the generation of induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2(6):525–528. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huangfu D, Maehr R, Guo W, et al. Induction of pluripotent stem cells by defined factors is greatly improved by small-molecule compounds. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26(7):795–797. doi: 10.1038/nbt1418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Silva J, Barrandon O, Nichols J, et al. Promotion of reprogramming to ground state pluripotency by signal inhibition. PLoS Biol. 2008;6(10):e253. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060253. published online 21 October 2008, doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0060253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou H, Wu S, Joo JY, et al. Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells using recombinant proteins. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4(5):381–384. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim D, Kim CH, Moon JI, et al. Generation of human induced pluripotent stem cells by direct delivery of reprogramming proteins. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4(6):472–476. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aoi T, Yae K, Nakagawa M, et al. Generation of pluripotent stem cells from adult mouse liver and stomach cells. Science. 2008;321(5889):699–702. doi: 10.1126/science.1154884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nakagawa M, Koyanagi M, Tanabe K, et al. Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells without Myc from mouse and human fibroblasts. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26(1):101–106. doi: 10.1038/nbt1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Park IH, Zhao R, West JA, et al. Reprogramming of human somatic cells to pluripotency with defined factors. Nature. 2008;451(7175):141–146. doi: 10.1038/nature06534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hotta A, Ellis J. Retroviral vector silencing during iPS cell induction: An epigenetic beacon that signals distinct pluripotent states. J Cell Biochem. 2008;105(4):940–948. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aasen T, Raya A, Barrero MJ, et al. Efficient and rapid generation of induced pluripotent stem cells from human keratinocytes. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26(11):1276–1284. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim JB, Zaehres H, Wu G, et al. Pluripotent stem cells induced from adult neural stem cells by reprogramming with two factors. Nature. 2008;454(7204):646–650. doi: 10.1038/nature07061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Giorgetti A, Montserrat N, Aasen T, et al. Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells from human cord blood using OCT4 and SOX2. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5(4):353–357. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim JB, Sebastiano V, Wu G, et al. Oct4-induced pluripotency in adult neural stem cells. Cell. 2009;136(3):411–419. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hanna J, Wernig M, Markoulaki S, et al. Treatment of sickle cell anemia mouse model with iPS cells generated from autologous skin. Science. 2007;318(5858):1920–1923. doi: 10.1126/science.1152092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xu D, Alipio Z, Fink LM, et al. Phenotypic correction of murine hemophilia A using an iPS cell-based therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(3):808–813. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812090106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nelson TJ, Martinez-Fernandez A, Yamada S, et al. Repair of acute myocardial infarction with induced pluripotent stem cells induced by human stemness factors. Circulation. 2009;120(5):408–416. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.865154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cattoglio C, Facchini G, Sartori D, et al. Hot spots of retroviral integration in human CD34+ hematopoietic cells. Blood. 2007;110(6):1770–1778. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-01-068759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Montini E, Cesana D, Schmidt M, et al. Hematopoietic stem cell gene transfer in a tumor-prone mouse model uncovers low genotoxicity of lentiviral vector integration. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24(6):687–696. doi: 10.1038/nbt1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mali P, Ye Z, Hommond HH, et al. Improved efficiency and pace of generating induced pluripotent stem cells from human adult and fetal fibroblasts. Stem Cells. 2008;26(8):1998–2005. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhao Y, Yin X, Qin H, et al. Two supporting factors greatly improve the efficiency of human iPSC generation. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3(5):475–479. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brambrink T, Foreman R, Welstead GG, et al. Sequential expression of pluripotency markers during direct reprogramming of mouse somatic cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2(2):151–159. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stadtfeld M, Maherali N, Breault DT, et al. Defining molecular cornerstones during fibroblast to iPS cell reprogramming in mouse. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2(3):230–240. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Maherali N, Ahfeldt T, Rigamonti A, et al. A high-efficiency system for the generation and study of human induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3(3):340–345. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hockemeyer D, Soldner F, Cook EG, et al. A drug-inducible system for direct reprogramming of human somatic cells to pluripotency. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3(3):346–353. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shao L, Feng W, Sun Y, et al. Generation of iPS cells using defined factors linked via the self-cleaving 2a sequences in a single open reading frame. Cell Res. 2009;19(3):296–306. doi: 10.1038/cr.2009.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sommer CA, Stadtfeld M, Murphy GJ, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cell generation using a single lentiviral stem cell cassette. Stem Cells. 2009;27(3):543–549. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2008-1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chang CW, Lai YS, Pawlik KM, et al. Polycistronic lentiviral vector for "Hit and run" Reprogramming of adult skin fibroblasts to induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells. 2009;27(5):1042–1049. doi: 10.1002/stem.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Carey BW, Markoulaki S, Hanna J, et al. Reprogramming of murine and human somatic cells using a single polycistronic vector. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(1):157–162. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811426106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wernig M, Lengner CJ, Hanna J, et al. A drug-inducible transgenic system for direct reprogramming of multiple somatic cell types. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26(8):916–924. doi: 10.1038/nbt1483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Okita K, Nakagawa M, Hyenjong H, et al. Generation of mouse induced pluripotent stem cells without viral vectors. Science. 2008;322(5903):949–953. doi: 10.1126/science.1164270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gonzalez F, Barragan Monasterio M, Tiscornia G, et al. Generation of mouse-induced pluripotent stem cells by transient expression of a single nonviral polycistronic vector. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(22):8918–8922. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901471106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yates J, Warren N, Reisman D, et al. A cis-acting element from the Epstein-Barr viral genome that permits stable replication of recombinant plasmids in latently infected cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984;81(12):3806–3810. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.12.3806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yates JL, Warren N, Sugden B. Stable replication of plasmids derived from Epstein–Barr virus in various mammalian cells. Nature. 1985;313(6005):812–815. doi: 10.1038/313812a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Leight ER, Sugden B. Establishment of an oriP replicon is dependent upon an infrequent, epigenetic event. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21(13):4149–4161. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.13.4149-4161.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yates JL, Guan N. Epstein-Barr virus-derived plasmids replicate only once per cell cycle and are not amplified after entry into cells. J Virol. 1991;65(1):483–488. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.1.483-488.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nanbo A, Sugden A, Sugden B. The coupling of synthesis and partitioning of EBV's plasmid replicon is revealed in live cells. EMBO J. 2007;26(19):4252–4262. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yu J, Hu K, Smuga-Otto K, et al. Human induced pluripotent stem cells free of vector and transgene sequences. Science. 2009;324(5928):797–801. doi: 10.1126/science.1172482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stadtfeld M, Nagaya M, Utikal J, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cells generated without viral integration. Science. 2008;322(5903):945–949. doi: 10.1126/science.1162494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhou W, Freed CR. Adenoviral gene delivery can reprogram human fibroblasts to induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells. 2009;27(11):2667–2674. doi: 10.1002/stem.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Soldner F, Hockemeyer D, Beard C, et al. Parkinson's disease patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells free of viral reprogramming factors. Cell. 2009;136(5):964–977. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mc Clintock B. The origin and behavior of mutable loci in maize. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1950;36(6):344–355. doi: 10.1073/pnas.36.6.344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cary LC, Goebel M, Corsaro BG, et al. Transposon mutagenesis of baculoviruses: Analysis of Trichoplusia ni transposon IFP2 insertions within the FP-locus of nuclear polyhedrosis viruses. Virology. 1989;172(1):156–169. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(89)90117-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fraser MJ, Ciszczon T, Elick T, et al. Precise excision of TTAA-specific lepidopteran transposons piggyBac (IFP2) and tagalong (TFP3) from the baculovirus genome in cell lines from two species of Lepidoptera. Insect Mol Biol. 1996;5(2):141–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.1996.tb00048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Woltjen K, Michael IP, Mohseni P, et al. piggyBac transposition reprograms fibroblasts to induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2009;458(7239):766–770. doi: 10.1038/nature07863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kaji K, Norrby K, Paca A, et al. Virus-free induction of pluripotency and subsequent excision of reprogramming factors. Nature. 2009;458(7239):771–775. doi: 10.1038/nature07864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wang W, Lin C, Lu D, et al. Chromosomal transposition of PiggyBac in mouse embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(27):9290–9295. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801017105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mermer B, Colb M, Krontiris TG. A family of short, interspersed repeats is associated with tandemly repetitive DNA in the human genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84(10):3320–3324. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.10.3320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nelson TJ, Terzic A. Induced pluripotent stem cells: Reprogrammed without a trace. Regen Med. 2009;4(3):333–335. doi: 10.2217/rme.09.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Leblois H, Roche C, Di Falco N, et al. Stable transduction of actively dividing cells via a novel adenoviral/episomal vector. Mol Ther. 2000;1(4):314–322. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2000.0042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Utikal J, Polo JM, Stadtfeld M, et al. Immortalization eliminates a roadblock during cellular reprogramming into iPS cells. Nature. 2009;460(7259):1145–1148. doi: 10.1038/nature08285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Li H, Collado M, Villasante A, et al. The Ink4/Arf locus is a barrier for iPS cell reprogramming. Nature. 2009;460(7259):1136–1139. doi: 10.1038/nature08290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kawamura T, Suzuki J, Wang YV, et al. Linking the p53 tumour suppressor pathway to somatic cell reprogramming. Nature. 2009;460(7259):1140–1144. doi: 10.1038/nature08311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Marion RM, Strati K, Li H, et al. A p53-mediated DNA damage response limits reprogramming to ensure iPS cell genomic integrity. Nature. 2009;460(7259):1149–1153. doi: 10.1038/nature08287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Banito A, Rashid ST, Acosta JC, et al. Senescence impairs successful reprogramming to pluripotent stem cells. Genes Dev. 2009;23(18):2134–2139. doi: 10.1101/gad.1811609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hong H, Takahashi K, Ichisaka T, et al. Suppression of induced pluripotent stem cell generation by the p53-p21 pathway. Nature. 2009;460(7259):1132–1135. doi: 10.1038/nature08235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]