Abstract

Heat shock proteins (HSPs) provide a useful system for studying developmental patterns in the digenetic Leishmania parasites, since their expression is induced in the mammalian life form. Translation regulation plays a key role in control of protein coding genes in trypanosomatids, and is directed exclusively by elements in the 3′ untranslated region (UTR). Using sequential deletions of the Leishmania Hsp83 3′ UTR (888 nucleotides [nt]), we mapped a region of 150 nt that was required, but not sufficient for preferential translation of a reporter gene at mammalian-like temperatures, suggesting that changes in RNA structure could be involved. An advanced bioinformatics package for prediction of RNA folding (UNAfold) marked the regulatory region on a highly probable structural arm that includes a polypyrimidine tract (PPT). Mutagenesis of this PPT abrogated completely preferential translation of the fused reporter gene. Furthermore, temperature elevation caused the regulatory region to melt more extensively than the same region that lacked the PPT. We propose that at elevated temperatures the regulatory element in the 3′ UTR is more accessible to mediators that promote its interaction with the basal translation components at the 5′ end during mRNA circularization. Translation initiation of Hsp83 at all temperatures appears to proceed via scanning of the 5′ UTR, since a hairpin structure abolishes expression of a fused reporter gene.

Keywords: Leishmania, translation regulation, Hsp83, 3′ UTR, polypyrimidine tract, scanning of 5′ UTR

INTRODUCTION

Trypanosomatids are ancient eukaryotes that belong to the kinetoplastid order and are known for their unusual molecular features. Transcription of mRNAs is polycistronic, and the primary transcripts are further processed by trans-splicing and polyadenylation, to yield the monocistronic mature transcripts. To date, no conventional RNA pol II promoters for activating transcription of protein coding genes were identified (Martinez-Calvillo et al. 2003), although epigenetic effects appear to have a functional impact (Siegel et al. 2009). As a result, steady-state levels of differentially expressed genes are controlled mainly by post-transcriptional events such as mRNA processing and stability (Clayton and Shapira 2007). Recent evidence obtained from comparing the Leishmania transcriptome with its proteome indicates that translation regulation plays a key role in assigning the developmental pattern of gene expression (Rosenzweig et al. 2008).

Heat shock genes are useful as a model system for differential translation during the life cycle of Leishmania, as their de novo synthesis increases dramatically at mammalian-like temperatures (Shapira et al. 1988; Garlapati et al. 1999). This pattern of regulation can be efficiently conferred onto a reporter gene when flanked by intergenic regions (IRs) that are derived from the Hsp83 gene cluster, as these provide signals for mRNA processing and translation. Using transgenic Leishmania cell lines we previously showed that preferential translation of a reporter gene that is fused to the Hsp83 IRs is controlled almost exclusively by the 3′ untranslated region (UTR). The 3′ UTR alone confers a pattern of regulation similar to that of the endogenous gene, whereas the 5′ UTR has only a synergistic effect, and by itself cannot cause an increase in translation during heat shock (Zilka et al. 2001). This pattern of regulation in Leishmania varies from that of higher eukaryotes, since the 5′ UTRs of the Drosophila and human Hsp70 genes can efficiently induce preferential translation of a reporter gene at elevated temperatures (Lindquist 1980). Former analysis of the 3′ UTR of Leishmania Hsp83 (888 nucleotides [nt]) using sequential deletions, mapped the regulatory region to positions 201–472. However, this element was required, but not sufficient to induce preferential translation onto the reporter gene. The minimal region that could confer this pattern of expression included the proximal half of the 3′ UTR, positioned between nucleotides 1 and 472. Interestingly, preferential translation of the CAT transcript fused to this segment occurred despite its reduced stability at elevated temperatures (Zilka et al. 2001).

In prokaryotes, translation initiation is promoted by base-pairing between the Shine–Dalgarno (SD) element and a complementary sequence in the 16S rRNA. Hence, accessibility of the SD element is fundamental for translation initiation to occur (Narberhaus et al. 2006). A thermosensing mechanism caused by alterations in the RNA structure was reported for several operons that encode mainly small heat shock proteins in various rhizobial species (Chowdhury et al. 2003, 2006). Another example for a thermosensing RNA is rpoH, which encodes the heat shock factor sigma 32. Translation of its mRNA is up-regulated in response to temperature elevation, as a result of structural alterations in the 5′ UTR. At normal temperatures the SD box is part of a double-stranded region and is therefore not accessible to the 16S rRNA. During heat shock this region melts and the SD element becomes single-stranded, allowing it to pair with the 3′ end of the 16S rRNA and this promotes translation at elevated temperatures (Morita et al. 1999).

Translation initiation in eukaryotes and prokaryotes follow different pathways. The eukaryotic initiation complex usually assembles on the cap structure at the 5′ end of the transcript and scans the 5′ UTR until it reaches the first AUG codon, where the ribosome assembles and translation initiates. Alternatively, translation initiation can proceed in a cap-independent manner that involves complex structures in the 5′ UTR. In such cases, the small ribosomal subunit binds directly to a region adjacent to the first AUG, denoted as the internal ribosome entry site (IRES) (Holcik et al. 2000). It has been suggested that, since cap-dependent translation is inhibited during thermal stress, translation of heat shock transcripts may be mediated by cap-independent translation (Hernandez et al. 2004) or by ribosome shunting (Yueh and Schneider 2000).

To examine whether the temperature switches which are experienced by the parasites during their life cycle affect the structure of the regulatory element in the Hsp83 3′ UTR, we combined experimental and computational approaches. We show that the regulatory region folds into a highly probable structure, which contains a polypyrimidine tract (PPT) and partially melts at mammalian-like temperatures.

RESULTS

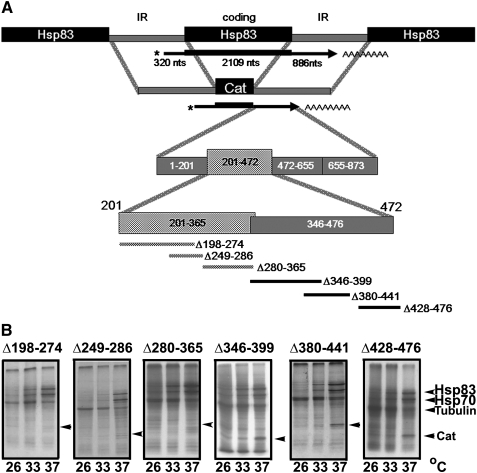

A region of 150 base pairs in the 3′ UTR is required for preferential translation of Hsp83

Temperature switches are a key parameter that drives stage-specific expression during the life cycle of Leishmania parasites. Heat shock transcripts are preferentially translated at temperatures typical of mammalian hosts, while translation of cytoplasmic proteins is reduced. Different species vary in their temperature sensitivities, thus stage transformation occurs at a defined range of temperatures (Shapira et al. 1988; Garlapati et al. 1999). The 3′ UTR plays a key role in translation regulation of stage-specific genes such as Hsp83. Previous studies using sequential deletions mapped the Hsp83 regulatory region to positions 201–472 in the 3′ UTR. To narrow down the sequences that are essential for conferring this pattern of regulation six block deletions were introduced into the 3′ UTR, removing sequences 198–274, 249–286, 280–365, 346–399, 380–441, and 428–476. The mutated IR regions were used to construct a series of pHCH expression vectors, in which the CAT gene (C) was flanked by a complete upstream IR (H) and a mutated downstream IR (H) (Fig. 1A). The downstream IR extended until the next coding region, to maintain the signals for RNA processing (LeBowitz et al. 1993). Each of the six deletion constructs was introduced into the pX expression vector and further used to generate stable cell lines. Correct polyadenylation was validated by 3′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (3′ RACE) analysis.

FIGURE 1.

Preferential translation of Hsp83 is directed by sequences 201–346 in the 3′ UTR. (A) The CAT reporter gene was flanked by complete IRs derived from the Hsp83 genomic cluster, so that the signals for RNA processing were maintained on both sides. The resulting constructs were cloned into the pX transfection vector of Leishmania and used to generate stable cell lines. (B) De novo synthesis of the CAT reporter gene was examined by metabolic labeling of the transgenic parasite cells grown at 26°C, and after their preincubation at 33°C, or 37°C, during 60 min. Protein extracts were separated over 12% polyacrylamide gels. Migration of CAT, Hsp70, Hsp83, and the α- and β-Tubulins are marked with arrowheads.

To follow the effect of heat shock on de novo synthesis of the CAT reporter gene, cells were preincubated and then metabolically labeled at 26°C, 33°C, and 37°C. Analysis of the labeled proteins on SDS-polyacrylamide gels (Fig. 1B) showed that deletions 198–274, 249–286, and 280–365 completely prevented preferential translation of the CAT gene, whereas all the deletions within positions 346–476 had no such effect. It was therefore concluded that nucleotides 198–346 were required for driving preferential translation.

Incorporating the Hsp83 segment 201–472 within the α-tubulin IR that was cloned downstream from the CAT reporter gene failed to confer preferential translation at elevated temperatures (data not shown), possibly due to its spatial inaccessibility and spacing considerations. Furthermore, the minimal 3′ UTR fragment that could confer preferential translation consisted of its proximal half, mapped to positions 1–472. Deletion of the distal half (nucleotides 472–873) did not change this expression pattern (Zilka et al. 2001). The relatively large size of the 3′ UTR fragment that can independently confer preferential translation raised the possibility that structural changes were involved.

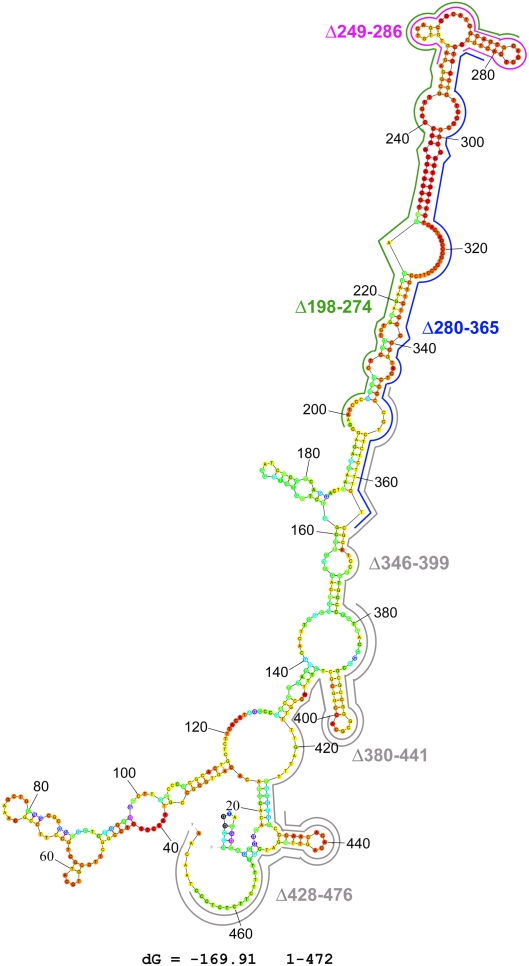

RNA secondary structure prediction for the regulatory region 1–472

RNA secondary structure can be predicted by software packages that are based on energy minimization, such as Mfold (Zuker 2003) and the Vienna RNA package (Hofacker 2003). These methods give reliable predictions for relatively short RNA segments (up to ∼150 nt), whereas for larger fragments they generate multiple outputs. In this study we used the recently developed algorithm 3.4-1 version of UNAfold with Mfold utilities version 4.0 (Markham and Zuker 2008) to generate a dot plot and further give a visual impression of how “well defined” the folding is (Zuker and Jacobson 1998). The predicted structure is shown in Figure 2. Interestingly, the different deletions that eliminate preferential translation (nucleotides 201–346) are positioned on a highly probable secondary structure, in which the nucleotides are marked as red.

FIGURE 2.

Structure prediction of the Hsp83 3′ UTR element 1–472 by UNAfold. Color annotation was used to indicate the propensity of individual nucleotides to participate in base-pairing and whether or not a predicted base pair is well determined. Forty colors that range from red (unusually well determined) through orange, yellow, green, blue, purple to black (poorly determined) are used (Zuker and Jacobson 1998). The structure with the lowest ΔG that was obtained using the Mfold program is shown, and the color of each nucleotide indicates its estimated P-value. The deletions which are described in Figure 1 are positioned on the predicted structure. Deletions that abolished preferential translation are colored in green (Δ198–274), purple (Δ249–286), and blue (Δ280–365). Deletions that did not affect preferential translation are marked in gray (Δ346–399, Δ380–441, and Δ428–476).

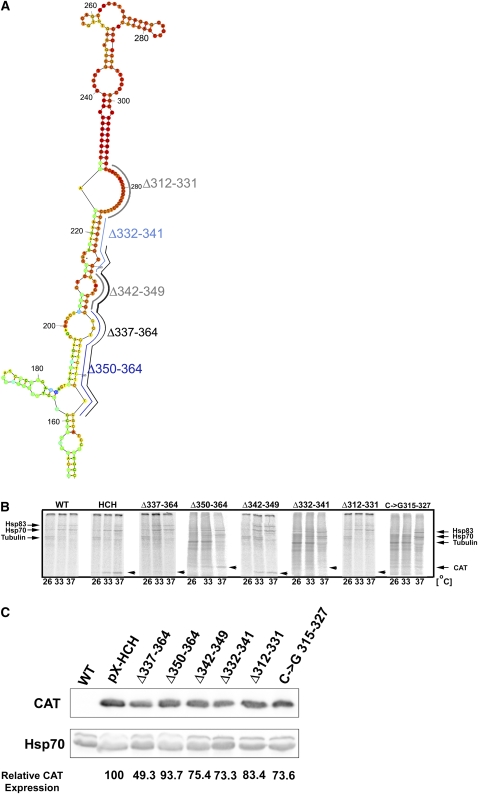

The PPT at positions 312–341 is essential for preferential translation at elevated temperatures

The Hsp83 “regulatory arm” (nucleotides 201–364) (Fig. 2) contains a long stretch of polypyrimidines, predicted to be partly single- and partly double-stranded. To test whether the PPT is essential for preferential translation of Hsp83 at elevated temperatures, small deletions and targeted replacement mutations were introduced into the 3′ UTR (Fig. 3A) and tested as described above. The effects of these mutations on de novo synthesis of the CAT–Hsp83 chimera are shown in Figure 3B. Deletion or exchange of the polypyrimidines that are predicted to be single-stranded (mutations Δ312–331 and the C-to-G exchanges at positions 315–327), as well as double-stranded (mutation Δ332–341), eliminated preferential translation of the reporter gene at elevated temperatures. Further downstream deletions eliminating nucleotides that contain non-PPT regions (Δ342–349) or PPT elements (Δ350–364) did not interfere with the induced translation at elevated temperatures (Fig. 3B). It appears that the regulatory element consists of the PPT that is located between positions 312 and 341, and comprises both single- and double-stranded regions (Δ312–331 and Δ332–341, respectively).

FIGURE 3.

Sequences 312–341 in the Hsp83 3′ UTR are essential for preferential translation during heat shock. (A) A map of mutations within the region 150–364 in the 3′ UTR of Hsp83. The modified IRs were cloned downstream from the CAT gene to generate 3′ UTRs. The upstream Hsp83 IR was not modified. The chimeric CAT–Hsp83 genes were cloned in the pX vector for transfection of Leishmania, and used to generate transgenic parasite cell lines. (B) Functional fine mapping of sequences that are required for preferential translation of the CAT–Hsp83 chimeric gene. Cells expressing the CAT gene under control of the mutated Hsp83 3′ UTR were grown at 26°C, or transferred to 33°C or 37°C for 1 h, and metabolically labeled for 30 min at the corresponding temperatures with 35[S]-labeled amino acids. Proteins were extracted, separated over 15% SDS-polyacrylamide gels, and autoradiogrammed in a PhosphorImager. Migration of Hsp83. Hsp70, the α- and β-tubulins, and CAT are marked with arrowheads. WT represents the nontransfected negative control cells which do not express CAT. pX-HCH represents transgenic cells expressing CAT under control of nonmodified Hsp83 IRs. Deletion mutations Δ312–331, Δ337–364, Δ332–341, and the C → G exchange mutation at positions 315–327 abrogated preferential translation of the CAT transcript. However, deletion mutations Δ350–364 and Δ342–349 did not interfere with the increased CAT translation at elevated temperatures. (C) Steady-state CAT expression at 26°C in cells transfected with the different 3′ UTR deletions. Cell extracts were separated over 15% SDS-polyacrylamide gels, blotted, and reacted with anti-CAT antibodies. Protein loads were evaluated by control reactions with antibodies against Hsp70. The level of CAT expression was quantified with Multigauge V3.0 and normalized against Hsp70. The values shown at the bottom of the figure represent a mean of two independent experiments.

Western analysis showed that, similar to Hsp83 (Argaman et al. 1994), a steady-state level of CAT expression was observed at 26°C. Furthermore, it appeared that most of the fine mutations caused a partial reduction in the steady-state level of CAT expression, irrespective of their effect on de novo synthesis at elevated temperatures (Fig. 3C).

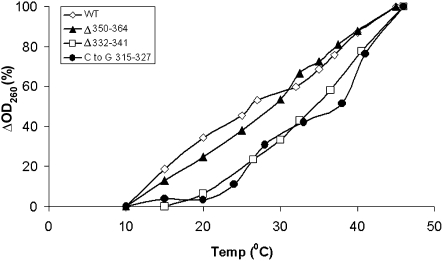

Thermal melting of the regulatory RNA region

RNA is subject to thermal melting; however, different RNAs may acquire variable melting patterns. To examine how temperature elevation affects the regulatory element, we tested its melting by monitoring changes in the UV absorbance at 260 nm as a function of temperature. It has been shown in the past that a collapse in the secondary structure of nucleic acids in response to extreme conditions leads to an increase in the optical density at 260 nm, by ∼15%–20% (Thomas 1951, 1993). Thus, the thermal stability of the wild-type and mutated 1–472 RNA fragments was evaluated by UV spectroscopy. The RNAs were incubated at temperatures that increased by increments of 5°C, between 10°C and 45°C. To compare between the melting patterns of the different RNA elements on a single plot, we expressed the ΔOD260 values for each curve as relative numbers that ranged from 0% to 100% (the ΔOD260 at the highest temperature served as 100%). The absorbance curves (Fig. 4) indicate a faster melting pattern for the RNA fragments that direct preferential translation at elevated temperatures (wild type and Δ350–364), as compared to the noninducing mutated RNA fragments (Δ332–341 and C to G exchange 315–327). The structure prediction of UTR fragments containing mutations that interfere with preferential translation at elevated temperatures gives a somewhat lower dG values, as compared to wild-type sequences (Supplemental Fig. 1).

FIGURE 4.

RNA melting curves of the wild-type and mutated 1–472 RNA fragments. Representative melting profiles were obtained by measuring the optical density of the RNA solutions (0.012 mg/mL) at temperatures that increased by increments of 5°C. The RNA was allowed to equilibrate for 10 min at each temperature, prior to monitoring the absorbance at 260 nm. The change in absorbance for each temperature (ΔOD260) was calculated relative to the starting point. The ΔOD260 values for each curve are expressed as relative numbers that range from 0% to 100% (the ΔOD260 at the highest temperature served as 100%).

The effect of temperature elevation on the secondary structure of RNA within the regulatory region was also monitored by the RNase H assay. RNase H cleaves RNA which is hybridized to a complementary DNA strand. Thus a short oligonucleotide can direct the cleavage of its complementary RNA sequence, given that the latter is single-stranded and accessible for hybridization with the oligonucleotide. Double-stranded RNA regions are therefore resistant to the enzymatic cleavage.

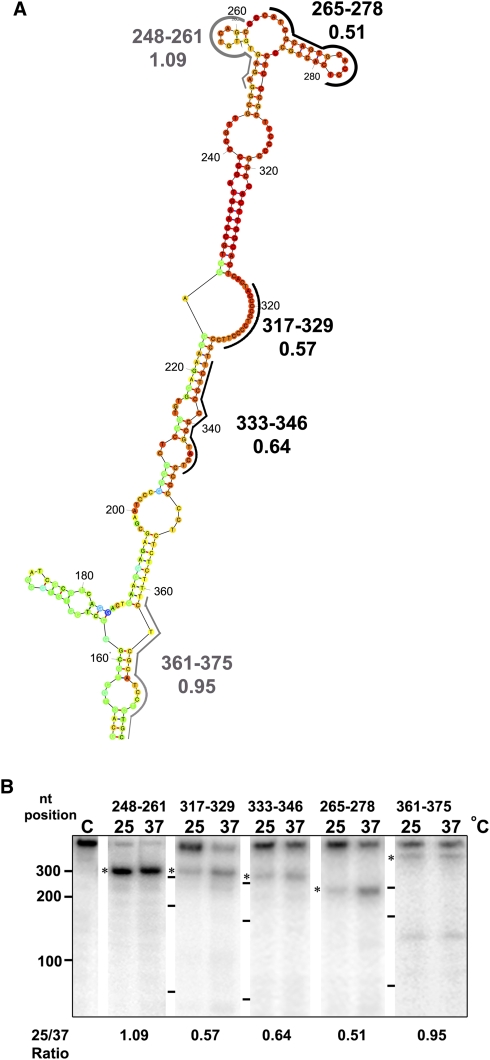

The RNA fragment that corresponds to sequences 1–472 of the Hsp83 3′ UTR was transcribed in vitro and labeled at its 5′ end. The radiolabeled RNA was incubated at 26°C and at 37°C, annealed with specific antisense oligonucleotides and subjected to cleavage by RNase H (Fig. 5A). Analysis of the resulting fragments over denaturing gels showed increased cleavage at 37°C in the presence of oligonucleotides 317–329, 333–346, and 265–278, but not with oligonucleotides 248–261 and 361–375 (Fig. 5B). Although the PPT at positions 317–329 is predicted to be single-stranded, its increased cleavage at elevated temperatures could indicate that this region stacks with short complementary purines, which are found along the regulatory region 1–472, to create a complex tertiary structure. Temperature elevation may melt these interactions, as appears from the RNase H cleavage pattern. Cleavage of the RNA fragment that corresponds to sequences 248–261 does not comply with the fact that part of this region is predicted to be double-stranded. In view of this result, we suggest that the short predicted stem that encompasses two pairs of nucleotides (255 with 260 and 254 with 261) is mostly open, generating a large loop between positions 252 and 267, which is constantly open. This stem indeed is colored with yellow, indicating that it is not “highly defined.” The results described above show that the regulatory region is thermosensitive and that specific regions are subject to melting that may increase their accessibility to regulatory components during translation.

FIGURE 5.

RNA melting measured by RNase H cleavage. (A) Location of the antisense oligonucleotides on the predicted RNA structure. The oligonucleotides used for the RNase H assay are positioned on the predicted RNA structure (black lines), and the ratio between the intensity of the two cleavage products is indicated (25/37). Black lettering represents regions that melt at elevated temperatures (25/37 < 1) and gray lettering marks regions that are not affected by temperature elevation (25/37 = 1). (B) RNase H cleavage directed by hybridization of the RNA fragment preincubated at different temperatures. The end-labeled RNA (1–472) was exposed to different temperatures (25°C or 37°C), then incubated with different oligonucleotides and cleaved by RNase H at the corresponding temperature. The RNase H cleavage products were separated over 6% denaturing polyacrylamide gels. Migration of the untreated full-length 1–472 RNA product is shown at the left. Products of the RNase H cleavage reaction following hybridization with oligonucleotides at different temperatures are marked with a star. The oligonucleotide positions in the 3′ UTR are indicated above the lanes. Size markers of 100, 200, and 300 nt are depicted at the left side of each panel (numbers at the far left and short lines between the panels). The ratio between the intensity of the two bands (25/37) is shown at the bottom of each panel.

Translation of Hsp83 initiates by scanning of the 5′ UTR

The results obtained thus far indicate rather unequivocally that preferential translation of Hsp83 in Leishmania is mediated by a regulatory element in the 3′ UTR unlike in higher eukaryotes, where preferential translation of Hsps requires the 5′ UTR. However, at this stage, it is still unclear how the 3′ UTR promotes preferential translation in these organisms. There are multiple reports on IRES-mediated translation of Hsps in higher eukaryotes, which does not involve scanning of the 5′ UTR. We therefore tested whether, despite the fact that the Hsp83 5′ UTR is exchangeable, preferential translation of the Hsp83–CAT hybrid mRNA proceeds via scanning of the 5′ UTR.

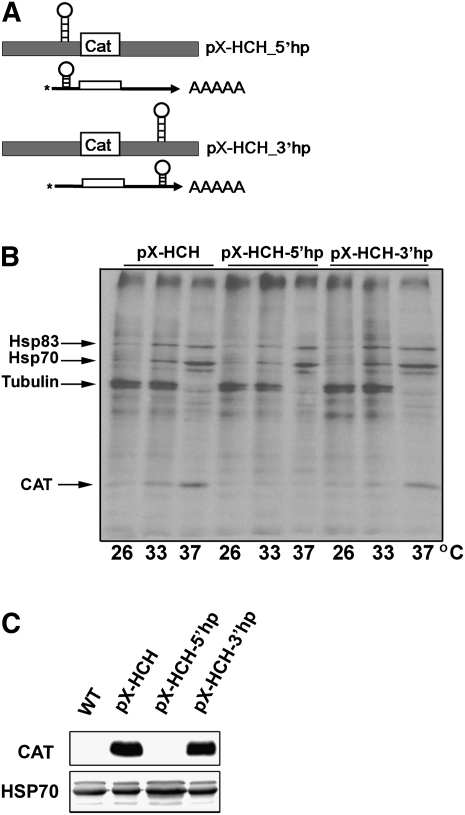

To examine whether translation of Hsp83 initiates by scanning of the 5′ UTR, or whether the ribosome can possibly target itself to the vicinity of the first AUG, a stable hairpin structure was introduced in the middle of the Hsp83 5′ UTR. This structure consisted of five BamHI linker repeats and was introduced at position 121 of the ∼320-nt long 5′ UTR (Fig. 6A). Addition of this strong secondary structure prevented CAT translation at either temperature, 26°C, 33°C, and 37°C, suggesting that the scanning of the 5′ UTR was interrupted (Fig. 6B). Furthermore, the presence of the hairpin structure at the 5′ UTR totally prevented any steady-state expression of the CAT reporter, as shown by Western analysis (Fig. 6C).

FIGURE 6.

Preferential translation of Hsp83 occurs via scanning of the 5′ UTR. (A) Introduction of a hairpin structure at the Hsp83 5′ and 3′ UTRs. A scheme of plasmids carrying the CAT gene flanked with Hsp83 IRs, with a foreign hairpin structure introduced either to the 5′ or to the 3′ UTRs, is shown. The CAT constructs were cloned into the pX transfection vector and used to generate transgenic Leishmania lines. (B) A hairpin structure introduced in the 5′ UTR has an inhibitory effect on CAT translation at both temperatures. Cells expressing the CAT gene under control of the Hsp83 IRs carrying a hairpin structure either at the 5′ or at the 3′ UTR were incubated for 1 h at different temperatures, 26°C, 33°C, or 37°C, and metabolically labeled with 35[S]-labeled methionine and cystein during 30 min at the corresponding temperatures. Proteins were extracted and separated over 15% SDS-polyacrylamide gels. The migration distances of Hsp83, Hsp70, tubulin, and the CAT reporter gene are marked by arrows. Introduction of a hairpin structure into the 5′ UTR inhibited the de novo translation of the CAT–Hsp83 chimera at all temperatures. (C) Steady-state CAT expression in cells transfected with a CAT–Hsp83 chimera carrying a hairpin structure at the 5′ (pX-HCH-5′hp) and 3′ (pX-HCH-3′hp) UTRs. Cell extracts were separated over 15% SDS-polyacrylamide gels, blotted, and reacted with anti-CAT antibodies. Protein loads were evaluated by control reactions with antibodies against Hsp70.

Since preferential translation of the Hsp83 gene is mediated by the 3′ UTR, we also examined the effect of a hairpin structure that was introduced downstream from the regulatory region (at position 655). As expected, this modification had no effect on de novo synthesis of the CAT reporter mRNA (Fig. 6B).

DISCUSSION

In trypanosomatids, stability and translation of stage-specific transcripts are regulated almost exclusively by 3′ UTRs, yet little is known on their mode of function. Since the developmental program of gene expression in these digenetic parasites is directed by changes in temperature and pH, heat shock genes provide an ideal system for understanding how environmental switches are perceived by the molecular machinery of these organisms.

In this study we performed a fine mapping of the 3′ UTR to characterize the element that is required for preferential translation of the Leishmania Hsp83. The experiments are based on former studies that identified the 3′ UTR as the region that confers this pattern of expression, originally highlighting a rather large regulatory region between nucleotides 201 and 472 (Zilka et al. 2001). However, the minimal fragment that could independently induce de novo synthesis at elevated temperatures consisted of the proximal half of the 3′ UTR (nucleotides 1–472). Implanting a smaller fragment (nucleotides 201–472) in a nonheat shock 3′ UTR could not confer this effect, suggesting that it possibly failed to assign a proper folding, or that it was not accessible to the translational machinery.

The computer-based secondary structure prediction reveals that the regulatory region in the Hsp83 3′ UTR is found on a well-defined arm that contains a long stretch of pyrimidines. The direct involvement of this PPT in preferential translation during heat shock was established by mutational analysis. A targeted deletion of the single- and double-stranded pyrimidine-rich regions (Δ312–331 and Δ332–341, respectively) prevented preferential translation of the CAT reporter transcript at elevated temperatures. Removal of sequences located further downstream (342–349 and 350–364) had no such effect. Altogether, the regulatory element lies between nucleotides 312 and 341.

The sequence of the Hsp83 3′ UTR element is highly conserved among different Leishmania species (Supplemental Fig. 2), but not with Trypanosoma brucei. However, a partially conserved pyrimidine-rich region, (71%; 460-CCACCUCACGUUCCUUUCCC-480), was found in the 3′ UTR of T. brucei Hsp83. UNAfold analysis predicted that this element is located within a well-defined structural arm (Supplemental Fig. 3), which is reminiscent of the parallel structure in the Leishmania transcripts. The actual involvement of this element in preferential translation is yet to be examined experimentally.

A similar picture is revealed for the Leishmania Hsp70 genes, where the downstream untranslated region directs their developmental expression pattern (Quijada et al. 2000). The Hsp70 gene cluster in Leishmania contains six copies. The transcript of the first five copies increases at elevated temperature and is translated with higher efficiency (Folgueira et al. 2005), similar to Hsp83. The transcript of the sixth copy contains a different 3′ UTR (Quijada et al. 1997) and follows a different regulatory pathway. The UNAfold package predicts that only the 3′ UTR of the heat-inducible Hsp70 I transcript contains a well-defined structural arm with a short PPT (data not shown). This finding is reminiscent of Hsp83 but should be further tested for its involvement in directing preferential translation of Hsp70.

Pyrimidine-rich regions serve as common regulatory elements during RNA processing, and their function is mediated by binding of specific splicing factors, such as the PPT binding protein (PTB). In addition to its role in alternative splicing (Singh et al. 1995; Perez et al. 1997), PTB was also implicated as an IRES trans-acting auxiliary factor (ITAF) that enhances cap-independent translation via the 5′ UTR (Mitchell et al. 2005; Song et al. 2005; Spriggs et al. 2005; Bushell et al. 2006). More recent reports indicate that PTB can promote translation through the 3′ UTR, as shown for the hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF-1α) (Galban et al. 2008) and of the ATP-Synthase β subunit (Reyes and Izquierdo 2007). However, it can also act as a translation repressor, based on studies with the 3′ UTR of Drosophila osk (Besse et al. 2009). It has been shown that the human PTB1 can bind to PPTs of different lengths, structured or single-stranded (Clerte and Hall 2009), thus PTB can readily facilitate the formation of RNA–protein regulatory complexes. The function of the PPT in the Hsp83 3′ UTR is not clear yet, and we do not have evidence that PTB is involved. However, preliminary results show that PTB1 from Leishmania (LmjF04.1170), a homolog of the T. brucei protein (Stern et al. 2009), can interact with the recently identified eIF4G of Leishmania (LeishIF4G-3; Yoffe et al. 2009) in a yeast-two hybrid assay (data not shown). We hypothesize that the regulatory PPT that we identified in the 3′ UTR of Hsp83 (nucleotides 312–334) may function as a binding target for a regulatory protein that in turn interacts with the basal translation initiation factors.

The regulatory region in the 3′ UTR of the Leishmania Hsp83 transcript is thermosensitive and undergoes a limited melting process, as observed by the RNase H assay, and by monitoring changes in the optical density of the RNA. RNA fragments that direct preferential translation during heat shock (wild type and Δ350–364) seem to melt faster than the noninducing fragments (Δ332–341 and C → G exchange between positions 315 and 327). Melting of the regulatory region may not be the only parameter that leads to preferential translation. However, in view of the circular model for translation initiation (Gingras et al. 1999), one can speculate that changes in the melting status of the 3′ UTR and spatial exposure of its regulatory elements can affect their accessibility to molecules that also interact with the translation initiation complex. The partial compatibility between the RNA structure prediction and the RNase H data may stem from the inability of current computer algorithms to deal with tertiary RNA structures. Thus, although the use of the older Mfold algorithm to predict RNA folds at different temperatures did not reveal changes in the “highly defined” region, tertiary and spatial alterations as well as base stacking effects cannot be excluded.

Temperature elevation seems to assign a multitude of regulatory traits on protein synthesis in Leishmania. Deciphering the mechanistic basis for this regulation is important for our understanding of stage differentiation processes. The 3′ UTRs of several amastigote-specific genes contain a conserved “amastin element” that is known to increase their translation in the mammalian life form of the parasite (Boucher et al. 2002). The amastin element has no sequence conservation with the 3′ UTR of Hsp83, and no structural conservation as well. In fact, the UNAfold predictions of this element do not reveal any well-defined structures as in the Hsp83 transcript, suggesting that the two pathways vary.

In Drosophila, the 5′ UTR of Hsp70 mRNA is required for efficient translation (Klemenz et al. 1985; McGarry and Lindquist 1985). It was previously shown that cap-dependent translation is inhibited during thermal stress (Hellen and Sarnow 2001), and that translation initiation of Hsp70 may be cap-independent and mediated by IRES elements (Hernandez et al. 2004). Previous reports on human Hsp70 showed that insertion of a stable hairpin in the 5′ UTR near the AUG initiation codon still allows direct translation of a reporter gene, excluding a scanning mechanism (Yueh and Schneider 2000). Other reports suggested that, similar to Drosophila, translation of the human Hsp70 is mediated by an IRES (Rubtsova et al. 2003).

For Hsp90, however, a dual regulation was established (Hsp90 is parallel to Hsp83 in Leishmania). The 5′ UTR of Drosophila Hsp90 possesses significant secondary structure elements that are typical to nonheat shock genes (Ahmed and Duncan 2004). It was suggested that temperature elevation reprograms translation of Hsp90 mRNA from cap-dependent to a cap-independent mechanism. This was shown by experiments in which translation of Hsp90 at a normal growth temperature was strongly inhibited by treatment with rapamycin, a drug that blocks cap-dependent protein synthesis. Such sensitivity was not observed during heat shock (Duncan 2008).

Insertion of a strong secondary structure in the Hsp83 5′ UTR prevents translation at normal temperatures as well as during heat shock, indicating that initiation proceeds through scanning of the 5′ UTR at all temperatures. It appears that the regulatory mechanism that drives preferential translation of Hsp83 in Leishmania varies dramatically from the parallel mechanism in higher eukaryotes. This is reflected not only by the key role assigned to the 3′ UTR, but also by the strict requirement for scanning of the 5′ UTR at elevated temperatures. These findings most probably rule out the involvement of an IRES element in translation regulation of Hsp83 in Leishmania.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Organisms

Leishmania amazonensis isolate MHOM/BR/77/LTB0016 was cultured in Schneider's medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), 4 mM L-glutamine, and 25 μg/mL gentamycin. Parasites were also grown in RPMI supplemented with 10% FCS, 4 mM L-glutamine, 25 μg/mL gentamycin, biotin 0.0001%, hemin 0.0005%, biopterin 0.002 μg/mL, HEPES 40 mM, and adenine 0.1 mM.

Plasmid construction

Site-directed mutagenesis was performed by overlap extension PCR, or by one-step mutagenesis using primers that contained the target mutation, on a pBluescript-based plasmid in which the Hsp83 IR (M92925) was cloned between the PstI and SalI restriction sites (pKS83PS). A list of primers that was used for the mutagenesis is provided in Supplemental Table 1. The mutated IR was excised from the pKS83PS plasmid by cleavage with BclI and BamHI and the fragment was ligated into the BamHI site downstream from the CAT coding gene, in a pX plasmid that already contained the CAT coding gene (C) fused with an upstream IR from the Hsp83 (H) cluster (pXHC). Thus, the mutated IR was introduced downstream from the CAT coding gene. Modification of the 5′ UTR was done in a similar approach, and the alteration was performed on a plasmid that contained the IR of Hsp83 (pKS83). The modified IR was excised by BclI and cloned into the BamHI site of pXCH.

Isolation of RNA and 3′ RACE analysis

Total RNA was extracted from cells incubated at 26°C, and at different time points following their transfer to 33°C with the TRI Reagent (Scientific Research Laboratories). The proper polyadnylation sites were verified by 3′ RACE, as previously described (Zilka et al. 2001).

Transfections

Plasmid DNA was electroporated into L. amazonensis parasites as described (Laban and Wirth 1989), except that a double electrical pulse of 5.5 kV/cm at 25 μF in a Bio-Rad Gene Pulser apparatus was applied. Stably transfected lines were selected in the presence of 60 μg/mL Geneticin (G418, Sigma). Neomycin-resistant parasites appeared 10–14 d following transfection and were grown in the presence of 200 μg/mL Geneticin.

Metabolic labeling

Parasites were grown to a cell density of 3 × 107/mL. Cells (1 mL) were preincubated at 26°C, 33°C, and 37°C for 1 h and then labeled with 20 μCi of [35S] cystein-methionine protein labeling mix (1175 Ci/mmol) for 30 min at the corresponding temperatures. Following labeling, the cells were harvested at 4°C, washed twice with cold phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and lysed in SDS-PAGE sample buffer. Incorporation of the [35S] amino acids was measured by precipitation with trichloroacetic acid (TCA). Protein samples containing the same amount of incorporated radiolabel corresponded to a similar number of cells and were separated over 15% SDS-polyacrylamide gels. The gels were dried and further processed for fluorography. Migration of the CAT reporter gene was validated by the use of specific anti-CAT antibodies.

In vitro transcription and end labeling of RNA

RNA that corresponds to positions 1–472 in the 3′ UTR of Hsp83 was transcribed in vitro from the T7 promoter, using a PCR-based DNA template. Template DNA derived from the Hsp83 3′ UTR was amplified by PCR from pKS83 with the forward primer 4–21s (5′-GGTACGGCAGCGGCACAC-3′) and the reverse primer 450–472as (5′-TTGTTAGGGAGAGAAGAAAAACG-3′). A T7 RNA polymerase promoter was added in a reamplification reaction with the forward primer 4–19T7s (5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGTACGGCAGCGGCAC-3′; the promoter sequences are underlined) and the reverse primer 450–472as (see above). Amplification was performed in a total volume of 50 μL with 50 pmol of each primer, 100 μM of each dNTP, and 4 U of BIO-X-ACT short DNA polymerase (Bioline) in a buffer provided by the manufacturer. Cycling conditions were as follows: 5 min denaturation at 95°C, followed by 29 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 30 sec, annealing at 57°C for 40 sec, and elongation at 68°C for 40 sec. Reamplification was performed under the same conditions, except for the annealing temperature, which was 59°C.

Transcription was performed with 1 μg of PCR product as template for 2 h at 37°C in a total volume of 100 μL. The reaction contained 40 U of T3 RNA polymerase (Promega), 2.5 mM of each rNTP, buffer (provided by the manufacturer: 40 mM Tris at pH 7.9, 6 mM MgCl2, 2 mM spermidine, and 10 mM NaCl), and 100 U of RNasin (Promega). The reaction was stopped by freezing in liquid nitrogen. Five units of DNase RNase free (Promega) were added and the reaction was incubated for additional 30 min at 37°C. The DNase was inactivated by addition of 0.2 M EDTA at pH 8 (2 μL) and by incubation at 65°C for 20 min. Loading buffer was added (95% formamide, 20 mM EDTA at pH 8, 0.05% bromophenol blue, 0.05% xylene blue) and samples were separated on a 4% polyacrylamide/7 M urea gel. Following electrophoresis the product was excised and eluted in 600 μL of RNA extraction buffer (0.3 M NaAc, 0.1% SDS, 1 mM EDTA at pH 8) overnight at room temperature. The transcript was purified over a column of the RNeasy MinElute cleanup kit (Qiagen) and eluted in 30 μL of DEPC-treated ddH20.

For 5′ end labeling the RNA (∼0.1 μg) was dissolved in water, incubated at 85°C for 10 min in the presence of DTT (4 mM), and cooled on ice for 2 min. Labeling was performed with [γ32P] ATP (20 μCi, Amersham) in a buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl at pH 7.6, 10 mM MgCl2, 5 mM DTT, 0.1 mM spermidine, and 0.1 mM EDTA, by 10 U of T4 Polynucleotide kinase (Fermentas). Unincorporated nucleotides were removed by applying the mixture on a G-50 spin column, and the labeled fragment was gel-purified.

RNase H protection analysis

RNA (∼1 ng per reaction) labeled at the 5′ end was incubated for 2 h at 26°C or 37°C in the reaction buffer (0.2 M Tris-HCl at pH 7.5, MgCl2 0.05 M, 0.02 M DTT), at a total volume of 8 μL per reaction. The RNA was then annealed with 1 μL of a 1 μM oligonucleotide solution for 5 min at the corresponding temperature. One unit of RNase H (Ambion) was added to the reaction mixture followed by a further incubation of 5 min at the corresponding temperature. The reaction was stopped by the addition of loading buffer and samples were separated over 6% polyacrylamide/7 M urea gels. Dried gels were visualized by PhosphorImager analysis.

Analysis by UV melting curves

RNA transcribed in vitro was adjusted to ∼0.3 OD at 260 nm. The RNA was heated at increments of 5°C in ddH2O, or PBS at pH 7 and maintained at each temperature for 10 min prior to measuring absorbance in a JASCO V530 spectrophotometer equipped with a cell holder that was used to maintain the requested temperature by a circulating bath. Measurements were taken at temperature increments that ranged between 10°C and 50°C. The OD260 values for the melting process were normalized and plotted against the temperature.

Computer prediction of the RNA secondary structure

The 3.4-1 version of UNAfold (Markham and Zuker 2005, 2008) with Mfold utilities version 4.0 was used to determine the probability for each nucleotide to be found in a single- or double-stranded form. This software package, among many other capabilities, generates a dot plot which gives a visual impression of how well defined the folding is. The program evaluates each nucleotide for its ability to pair with other nucleotides, and assigns a P-value for each nucleotide. A low P-value indicates that there are only a few base-pairing possibilities and nucleotides with P = 0 are single-stranded. A color annotation is used to indicate the propensity of individual nucleotides to participate in base pairs and whether or not a predicted base pair is well determined. Colors range from red (unusually well determined) to black (poorly determined) (Zuker and Jacobson 1998).

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Supplemental material can be found at http://www.rnajournal.org.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the German–Israel Foundation, Grant No. 728-23/2002, and the Israel Science Foundation, Grant No. 395/09, to M.S. We thank Michael Zuker from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute for providing us with the UNAfold algorithm.

Footnotes

Article published online ahead of print. Article and publication date are at http://www.rnajournal.org/cgi/doi/10.1261/rna.1874710.

REFERENCES

- Ahmed R, Duncan RF. Translational regulation of Hsp90 mRNA. AUG-proximal 5′-untranslated region elements essential for preferential heat shock translation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:49919–49930. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404681200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argaman M, Aly R, Shapira M. Expression of the heat shock protein 83 in Leishmania is regulated post transcriptionally. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1994;64:95–110. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(94)90138-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besse F, Lopez de Quinto S, Marchand V, Trucco A, Ephrussi A. Drosophila PTB promotes formation of high-order RNP particles and represses oskar translation. Genes & Dev. 2009;23:195–207. doi: 10.1101/gad.505709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boucher N, Wu Y, Dumas C, Dube M, Sereno D, Breton M, Papadopoulou B. A common mechanism of stage-regulated gene expression in Leishmania mediated by a conserved 3′-untranslated region element. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:19511–19520. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200500200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushell M, Stoneley M, Kong YW, Hamilton TL, Spriggs KA, Dobbyn HC, Qin X, Sarnow P, Willis AE. Polypyrimidine tract binding protein regulates IRES-mediated gene expression during apoptosis. Mol Cell. 2006;23:401–412. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury S, Ragaz C, Kreuger E, Narberhaus F. Temperature-controlled structural alterations of an RNA thermometer. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:47915–47921. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306874200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury S, Maris C, Allain FH, Narberhaus F. Molecular basis for temperature sensing by an RNA thermometer. EMBO J. 2006;25:2487–2497. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton C, Shapira M. Post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression in trypanosomes and leishmanias. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2007;156:93–101. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2007.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clerte C, Hall KB. The domains of polypyrimidine tract binding protein have distinct RNA structural preferences. Biochemistry. 2009;48:2063–2074. doi: 10.1021/bi8016872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan RF. Rapamycin conditionally inhibits Hsp90 but not Hsp70 mRNA translation in Drosophila: Implications for the mechanisms of Hsp mRNA translation. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2008;13:143–155. doi: 10.1007/s12192-008-0024-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folgueira C, Quijada L, Soto M, Abanades DR, Alonso C, Requena JM. The translational efficiencies of the two Leishmania infantum HSP70 mRNAs, differing in their 3′-untranslated regions, are affected by shifts in the temperature of growth through different mechanisms. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:35172–35183. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505559200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galban S, Kuwano Y, Pullmann R, Jr, Martindale JL, Kim HH, Lal A, Abdelmohsen K, Yang X, Dang Y, Liu JO, et al. RNA-binding proteins HuR and PTB promote the translation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1α. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:93–107. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00973-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garlapati S, Dahan E, Shapira M. Effect of acidic pH on heat shock gene expression in Leishmania. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1999;100:95–101. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(99)00037-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gingras AC, Raught B, Sonenberg N. eIF4 initiation factors: Effectors of mRNA recruitment to ribosomes and regulators of translation. Annu Rev Biochem. 1999;68:913–963. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellen CU, Sarnow P. Internal ribosome entry sites in eukaryotic mRNA molecules. Genes & Dev. 2001;15:1593–1612. doi: 10.1101/gad.891101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez G, Vazquez-Pianzola P, Sierra JM, Rivera-Pomar R. Internal ribosome entry site drives cap-independent translation of reaper and heat shock protein 70 mRNAs in Drosophila embryos. RNA. 2004;10:1783–1797. doi: 10.1261/rna.7154104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofacker IL. Vienna RNA secondary structure server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3429–3431. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holcik M, Sonenberg N, Korneluk RG. Internal ribosome initiation of translation and the control of cell death. Trends Genet. 2000;16:469–473. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(00)02106-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klemenz R, Hultmark D, Gehring WJ. Selective translation of heat shock mRNA in Drosophila melanogaster depends on sequence information in the leader. EMBO J. 1985;4:2053–2060. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb03891.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laban A, Wirth DF. Transfection of Leishmania enriettii and expression of chloramphenicol acetyltransferase gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1989;86:9119–9123. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.23.9119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeBowitz JH, Smith H, Beverley SM. Coupling of polyadenylation site selection and trans-splicing in Leishmania. Genes & Dev. 1993;7:996–1007. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.6.996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindquist S. Translational efficiency of heat induced messages in Drosophila melanogaster cells. J Mol Biol. 1980;137:151–158. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(80)90322-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markham NR, Zuker M. DINAMelt web server for nucleic acid melting prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:W577–W581. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markham NR, Zuker M. UNAFold: Software for nucleic acid folding and hybridization. Methods Mol Biol. 2008;453:3–31. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-429-6_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Calvillo S, Yan S, Nguyen D, Fox M, Stuart KD, Myler PJ. Transcription of Leishmania major Friedlin chromosome 1 initiates in both directions within a single region. Mol Cell. 2003;11:1291–1299. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00143-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGarry TJ, Lindquist S. The preferential translation of Drosophila hsp70 mRNA requires sequences in the untranslated leader. Cell. 1985;42:903–911. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90286-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell SA, Spriggs KA, Bushell M, Evans JR, Stoneley M, Le Quesne JP, Spriggs RV, Willis AE. Identification of a motif that mediates polypyrimidine tract-binding protein-dependent internal ribosome entry. Genes & Dev. 2005;19:1556–1571. doi: 10.1101/gad.339105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morita MT, Tanaka Y, Kodama TS, Kyogoku Y, Yanagi H, Yura T. Translational induction of heat shock transcription factor σ32: Evidence for a built-in RNA thermosensor. Genes & Dev. 1999;13:655–665. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.6.655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narberhaus F, Waldminghaus T, Chowdhury S. RNA thermometers. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2006;30:3–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2005.004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez I, Lin CH, McAfee JG, Patton JG. Mutation of PTB binding sites causes misregulation of alternative 3′ splice site selection in vivo. RNA. 1997;3:764–778. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quijada L, Soto M, Alonso C, Requena JM. Analysis of post-transcriptional regulation operating on transcription products of the tandemly linked Leishmania infantum hsp70 genes. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:4493–4499. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.7.4493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quijada L, Soto M, Alonso C, Requena JM. Identification of a putative regulatory element in the 3′-untranslated region that controls expression of HSP70 in Leishmania infantum. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2000;110:79–91. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(00)00258-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes R, Izquierdo JM. The RNA-binding protein PTB exerts translational control on 3′-untranslated region of the mRNA for the ATP synthase β-subunit. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;357:1107–1112. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.04.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenzweig D, Smith D, Opperdoes F, Stern S, Olafson RW, Zilberstein D. Retooling Leishmania metabolism: From sand fly gut to human macrophage. FASEB J. 2008;22:590–602. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-9254com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubtsova MP, Sizova DV, Dmitriev SE, Ivanov DS, Prassolov VS, Shatsky IN. Distinctive properties of the 5′-untranslated region of human hsp70 mRNA. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:22350–22356. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303213200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapira M, McEwen JG, Jaffe CL. Temperature effects on molecular processes which lead to stage differentiation in Leishmania. EMBO J. 1988;7:2895–2901. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03147.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel TN, Hekstra DR, Kemp LE, Figueiredo LM, Lowell JE, Fenyo D, Wang X, Dewell S, Cross GA. Four histone variants mark the boundaries of polycistronic transcription units in Trypanosoma brucei. Genes & Dev. 2009;23:1063–1076. doi: 10.1101/gad.1790409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh R, Valcarcel J, Green MR. Distinct binding specificities and functions of higher eukaryotic polypyrimidine tract-binding proteins. Science. 1995;268:1173–1176. doi: 10.1126/science.7761834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y, Tzima E, Ochs K, Bassili G, Trusheim H, Linder M, Preissner KT, Niepmann M. Evidence for an RNA chaperone function of polypyrimidine tract-binding protein in picornavirus translation. RNA. 2005;11:1809–1824. doi: 10.1261/rna.7430405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spriggs KA, Bushell M, Mitchell SA, Willis AE. Internal ribosome entry segment-mediated translation during apoptosis: The role of IRES-trans-acting factors. Cell Death Differ. 2005;12:585–591. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern MZ, Gupta SK, Salmon-Divon M, Haham T, Barda O, Levi S, Wachtel C, Nilsen TW, Michaeli S. Multiple roles for polypyrimidine tract binding (PTB) proteins in trypanosome RNA metabolism. RNA. 2009;15:648–665. doi: 10.1261/rna.1230209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas R. On the existence of labile bonds in secondary structures of the nucleic acids' molecule. Experientia. 1951;7:261–262. doi: 10.1007/BF02154543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas R. The denaturation of DNA. Gene. 1993;135:77–79. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90051-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoffe Y, Leger M, Zinoviev A, Zuberek J, Darzynkiewicz E, Wagner G, Shapira M. Evolutionary changes in the Leishmania eIF4F complex involve variations in the eIF4E–eIF4G interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:3243–3253. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yueh A, Schneider RJ. Translation by ribosome shunting on adenovirus and hsp70 mRNAs facilitated by complementarity to 18S rRNA. Genes & Dev. 2000;14:414–421. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zilka A, Garlapati S, Dahan E, Yaolsky V, Shapira M. Developmental regulation of heat shock protein 83 in Leishmania. 3′ processing and mRNA stability control transcript abundance, and translation is directed by a determinant in the 3′-untranslated region. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:47922–47929. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108271200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuker M. Mfold web server for nucleic acid folding and hybridization prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3406–3415. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuker M, Jacobson AB. Using reliability information to annotate RNA secondary structures. RNA. 1998;4:669–679. doi: 10.1017/s1355838298980116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]