Abstract

Purpose

To assess the influence of treating developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH) with the abduction brace on locomotor development in children.

Methods

One hundred children treated for DDH served as the study group. There were 80 girls and 20 boys. The children’s average age at the beginning of the treatment was 8 weeks. The control group consisted of 100 healthy children with normal hips and without any locomotor system disorders. We have evaluated factors such as the age at which the treatment started, the duration of the treatment, the birth weight of the child and the time when the children started sitting and walking independently.

Results

On average, treatment with the abduction brace lasted 13 weeks (ranging from 6 to 26 weeks). The mean age at which the patients began to sit was 7 months, which was one week later compared to children from the control group (P = 0.28). The age at which they started walking was 12 months and 2 weeks, which was 3 weeks later than in the control group (P = 0.002).

Conclusion

For children with DDH, the abduction brace is a safe and effective method of treatment and, although the infants begin to walk about 3 weeks later compared to healthy children, this practice does not seriously affect the child’s locomotor development.

Keywords: Developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH), Treatment, Walking, Age

Introduction

Developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH) is the most frequent developmental disorder of the locomotor system. Depending on a given population, it is detected among 0.1–5.2% of newborns [1]. In Poland, its occurrence is estimated to be 4–6% [2]. In the neonatal period and early infancy, the most popular means of treating DDH are orthoses, whose common task is keeping the hip joints in flexion and abduction—human position. Among the most popular devices used in Poland are the Pavlik harness, the Frejka pillow and the Koszla abduction brace. Of these three, the abduction brace (Fig. 1), developed by Koszla in the 1960s, is the stiffest and the most solid [3].

Fig. 1.

Koszla abduction brace

If DDH is diagnosed early, treated properly and consistently, the treatment results are positive [4, 5]. Any inappropriate usage of stiff orthoses can lead to complications such as the development of avascular necrosis of the femoral head or transient paralysis of femoral and obturator nerves [6, 7]. Also, the necessity to immobilise the child’s legs and, by doing so, constrain their active lower limb motion raises concern among parents and physicians, who fear that it might cause a delay in the child’s locomotor development, specifically delayed sitting, standing and walking. In the literature available, we have not found any analyses concerning the influence of applying the abduction brace on the locomotor development in children with DDH.

The aim of this study was to assess whether DDH treated with the use of abduction braces impacted the locomotor development in children, estimated by the moment at which the child starts sitting, standing and walking.

Materials and methods

The study included 100 consecutive children with diagnosed DDH, who were treated in our baby hip clinic between January 2004 and December 2005 with the use of the abduction brace. The group consisted of 80 girls and 20 boys, all born between the 38 and 42 weeks of pregnancy. The mean birth weight was 3,460 g (standard deviation [SD] 395 g; range 2,430–4,760 g). We carried out clinical examinations to assess the stability of hip joints with the help of Barlow’s test [8] and Ortolani’s test [9]. Also, the passive range of motion was checked, including the range of hip abduction with the hip flex by 90°. The limitation of hip abduction was defined as 60° or below [10] or as an asymmetry equal to or above 20°[11].

Then, we performed ultrasonography of the hip using the Siemens Sonoline LX ultrasonograph (Germany) and a linear transducer of 5 MHz frequency according to Graf’s standards [12, 13]. For each child, we applied the abduction brace (Krakowskie Zakłady Sprzętu Ortopedycznego, Kraków, Poland). We registered the children’s age at the beginning of the treatment, the duration of the treatment and the degree of severity of the dysplasia (base upon Graf’s ultrasonographic classification). ‘Unaided sitting’ was defined as the child’s ability to sit unassisted for at least 30 s, without the need for propping up the back. ‘Unaided walking,’ in turn, was termed as their capacity to walk at least 3 m on their own. To reduce the risk of incorrect determination of the sitting or walking age, children were evaluated every 3 months after treatment. Parents from both treated and control groups were carefully instructed during visits about monitoring the baby’s motor development and what should they regard as sitting and walking ability for the study purposes. They were also advised to make the appointment for an unscheduled visit when their child begun to sit or walk.

The exclusion criteria involved other locomotor or nervous system disorders that could affect children’s locomotor development by delaying sitting and walking, DDH requiring plaster or operative treatment, and diagnosis of teratologic dislocation of the hip. Patients treated with the use of other orthoses (Pavlik harness) were excluded from the study. This allowed us to study a more homogeneous group of children treated with one method only (Koszla brace).

The control group consisted of 100 children, also 20 boys and 80 girls, with correctly shaped hips and with no locomotor organ or neurological disorders that could potentially impact walking. Parameters like birth weight and age were comparable to the studied group: the birth weight ranged from 2,480 to 4,300 g (mean 3,337 g).

Statistical methods

The statistical analysis was conducted with the use of the StatsDirect 2.6 program [14]. For assessing the normality of distribution, we applied Shapiro–Wilk’s test [15], and to estimate the intergroup differences in the non-parametric distribution, the Mann–Whitney test [16]. The differences at the level of P ≤ 0.05 were defined as statistically significant.

Results

Twenty-nine children (29%) had a family history of DDH. In 12 children, we diagnosed breech/pelvic presentation during pregnancy. The right hip was affected in 18 infants and the left hip was involved in 37 cases. Forty-five cases had bilateral hip involvement.

During our clinical examinations, we diagnosed abduction limitation in 40 children (40%), and in five children, we found eight hip joints (4%) to be unstable (positive Barlow’s and Ortolani’s tests). Based on Graf’s ultrasonographic classification, 67 hip joints were classified as IIB type, 24 as IIC type, three as D type, five hip joints as III group and one to the IV group. The mean duration of treatment was 13 weeks (range 6–24 weeks).

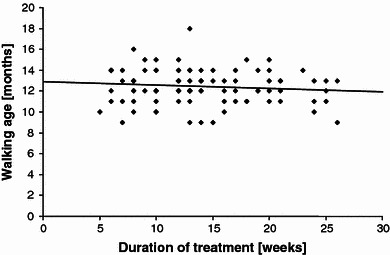

We have not found any statistically significant correlation between the duration of the treatment and walking age (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

The correlation between the duration of the treatment and walking age

Clinical examinations and ultrasonography revealed normal hip joints in all of the children. In 88 children, this was further confirmed by an X-ray. During observation, which lasted on average 18 months (range 10–26 months), we detected no symptoms of avascular necrosis of the femoral head.

The mean age at which the patients began to sit unassisted was 7 months (range 5–12 months; SD = 1.22), which was 1 week later compared to children from the control group—6 months and 3 weeks (range 5–9 months, SD = 0.82). This divergence was not statistically significant (P = 0.28). Furthermore, we have found no statistically significant difference between boys and girls in either the study and the control groups.

Children from the study group began to walk at a mean age of 12 months and 2 weeks (range 9–18 months; SD = 1.62) and there was a statistically significant difference in comparison to the control group (with no hip joint dysplasia), which was 11 months and 3 weeks (range 9–17 months, SD = 1.51; P = 0.002). This difference involved both girls and boys. In both groups, girls began to walk about 2 weeks earlier than boys; however, it was not statistically significant.

No correlation has been found between the age of the patients at the beginning of the treatment and sitting and walking ages.

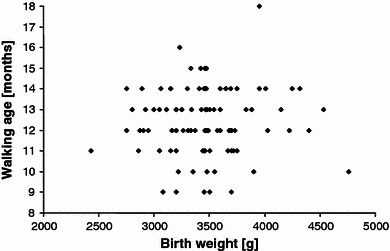

Similarly, we have not found any significant correlation between birth weight and the age at which the children started to walk (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

The correlation between birth weight and the age of walking

Discussion

It is commonly claimed that children with DDH or dislocation of the hip joint who have not been treated start walking slightly later than healthy children. This delay is about 2–3 months and usually does not exceed the average age of starting to walk [17]. In his study, Dunn [18] estimated that 20% of children with undiagnosed and untreated DDH do not start walking until 18 months. Kamath and Bennet [19] have demonstrated that the mean walking age in children not treated for this disorder was 13 months (range 9.5–18 months), which was, on average, 1 month later than in healthy children.

As our results show, conservative treatment of DDH with the abduction brace does not appear to significantly affect the child’s locomotor development. Though the three-week delay in walking is statistically significant, it does not influence their further locomotor development. Clinical observation of the same children after the treatment, at around the age of 2 years, clearly indicates that they are developing normally and are not in any way inferior to their peers who have not had DDH. This claim is a very strong argument to use in conversations with parents to dispel their possible fears connected with their children being treated for DDH.

The aim of our study was to evaluate the time of sitting and walking only. We believe that these are the abilities that may be the most strongly influenced by treatment. The information on whether orthotic management of DDH may influence further locomotor development may be very interesting. However, other factors (child lifestyle, obesity, coexisting orthopaedic disorders) may have a stronger impact on locomotor status in adolescence, so these were not included in our study.

The analysis of the study group did not reveal any correlations between the duration of the treatment and the age of walking. It could be the case that immobilising the child in the device is not the only cause of delayed walking. In fact, a hip joint dysplasia, which delays walking in children untreated for DDH, might also be a reason [18, 19]. Also, we did not discover any correlations between birth weight and the age of walking. The birth weight in the study group was higher than in the control group, yet, this difference was not statistically significant. However, various sources confirm that high birth weight is a risk factor for the occurrence of DDH [17].

In our analysis, the age of the patients at the beginning of the treatment was 8 weeks. It is likely that children whose DDH is diagnosed late need a longer treatment involving plaster or even surgery, which certainly does affect the child’s locomotor development. Such children, however, were not the focus of our study.

In conclusion, treating DDH by the abduction brace is a safe and effective method which does not significantly cause delays in the child’s locomotor development. The locomotor development in a child treated for DDH with the use of the abduction brace does not significantly depend on their birth weight, the duration of the treatment or the age at which the treatment was started. Further prospective studies on the treatment of DDH, its effectiveness, applying various orthoses (ranging in structure and mechanical properties) and the number of possible complications are certain to provide better and more desirable treatment results.

References

- 1.Wood MKMA, Conboy V, Benson MKD. Does early treatment by abduction splintage improve the development of dysplastic but stable neonatal hips? J Pediatr Orthop. 2000;20:302–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Czubak J, Kruczyński J (2003) Rozwojowa dysplazja i zwichnięcie stawu biodrowego. In: Marciniak W, Szulc A (eds) Wiktora Degi ortopedia i rehabilitacja. Wydawnictwo Lekarskie PZWL, Warszawa, p 165

- 3.Koszla MM. An apparatus for the treatment of congenital hip dysplasia. Chir Narządów Ruchu Ortop Pol. 1964;29:403–405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fredensborg N. The results of early treatment of typical congenital dislocation of the hip in Malmö. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1976;58:272–278. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.58B3.956242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mostert AK, Tulp NJ, Castelein RM. Results of Pavlik harness treatment for neonatal hip dislocation as related to Graf’s sonographic classification. J Pediatr Orthop. 2000;20:306–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bradley J, Wetherill M, Benson MKD. Splintage for congenital dislocation of the hip. Is it safe and reliable? J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1987;69:257–263. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.69B2.3818757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilkinson AG, Sherlock DA, Murray GD. The efficacy of the Pavlik harness, the Craig splint and the von Rosen splint in the management of neonatal dysplasia of the hip. A comparative study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2002;84:716–719. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.84B5.12571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barlow TG. Early diagnosis and treatment of congenital dislocation of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1962;44:292–301. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ortolani M. The classic: congenital hip dysplasia in the light of early and very early diagnosis. Clin Orthop. 1976;119:6–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cyvin KB. Congenital dislocation of the hip joint. Acta Paediatr Scand Suppl. 1977;263:1–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tönnis D. Congenital dysplasia and dislocation of the hip in children and adults. Berlin Heidelberg New York: Springer-Verlag; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Graf R. Fundamentals of sonographic diagnosis of infant hip dysplasia. J Pediatr Orthop. 1984;4:735–740. doi: 10.1097/01241398-198411000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Graf R. Classification of hip joint dysplasia by means of sonography. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1984;102:248–255. doi: 10.1007/BF00436138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Freemantle N. StatsDirect—Statistical software for medical research in the 21st century. Br Med J. 2000;321:1536. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7275.1536. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shapiro SS, Wilk MB. An analysis of variance test for normality. Biometrika. 1965;52:591–611. doi: 10.1093/biomet/52.3-4.591. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mann HB, Whitney DR. On a test of whether one of two random variables is stochastically larger than the other. Ann Math Stat. 1947;18:50–60. doi: 10.1214/aoms/1177730491. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herring JA. Tachdjian’s pediatric orthopaedics. 3. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2002. p. 88. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dunn PM. Is late walking a marker of congenital displacement of the hip? Arch Dis Child. 1990;65:1183–1184. doi: 10.1136/adc.65.10.1183-c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kamath SU, Bennet GC. Does developmental dysplasia of the hip cause a delay in walking? J Pediatr Orthop. 2004;24:265. doi: 10.1097/01241398-200405000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]