Abstract

This report describes a series of four cases of children between the ages 5 and 14 years with bone or joint infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis diagnosed between June 2006 and March 2008 in the Blackburn area of England. All of the cases were of South Asian descent. The diagnosis was confirmed by the presence of M. tuberculosis on the culture of bone, synovium or joint fluid, or by the presence of the typical histology of tuberculosis (TB). The sites of tuberculous disease were the hip joint, the sacro-iliac joint and the talus. A recent paper by Sandher et al. (J Bone Joint Surg Br 89:1379–1381, 2007) illustrated only two cases of childhood bone and joint TB in the same geographical area in the preceding 17 years.

Keywords: Tuberculosis, TB, Bone and joint infection, Bone TB, Joint TB, Tuberculosis surveillance, TB surveillance, Blackburn, TB hip, Sacro-iliac TB, TB talus

Introduction

There has been a notable increase in the number of cases of tuberculosis (TB) in the UK over recent years [1]. The Health Protection Agency (HPA) revealed preliminary surveillance data for 2007 confirming 8,496 cases of TB infections reported in the United Kingdom, at a rate of 14 per 100,000 population [2, 3]. This is an increase from 5,000 cases in 1987 to 8,116 cases in 2006 [4]. Data from the HPA in 2006 showed the largest incidence per 100,000 population in London (44.8), followed by the West Midlands (17.5), with the lowest in Northern Ireland (3.6). The North West region is above average, with an incidence of 10.2 cases per 100,000 population [5]. Blackburn had an incidence of 40.4 per 100,000 in 2006 and 33.3 per 100,000 in 2007 [6].

There has been a steady number of infections of bone and joint TB in children (aged less than 15 years at the time of diagnosis) recorded in the North West of England since 1999 [7]. The regional average is 1.7 per 100,000 children with TB infection of the bone or joints.

Patients and methods

A retrospective study from a comprehensive local database of cases of TB in the Blackburn, Hyndburn and Ribble Valley region was conducted. The database includes all patients diagnosed with TB in our area since 1978. The notes, radiographs and pathology information for the cases between 2006 and 2008 were then retrieved and scrutinised.

Patient A

A 5-year-old British-born boy of Pakistani descent presented to the Royal Blackburn Hospital A&E department in February 2008. He presented with a history of gradual worsening pain in the left ankle. There was no history of trauma, and the child was developmentally normal. There was no known TB contact, although the child had been to visit family in Pakistan when aged 2 years. The child had been given the Bacille Calmette–Guérin (BCG) vaccination at birth.

Examination of the left ankle revealed a warm, tender joint. There was discomfort on ankle movement; however, he retained a normal range of movement and was able to weight-bear. There was a raised erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 97 mm/h, a raised C-reactive protein (CRP) of 71 mg/L and a raised white blood cell count (WCC) of 12.1 gd/L.

Plain radiographs performed demonstrated a cystic lucency in the left talar bone (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Plain radiograph of the left ankle of Patient A (anteroposterior [AP] projection) illustrating a lesion in the mid-lateral talus bone

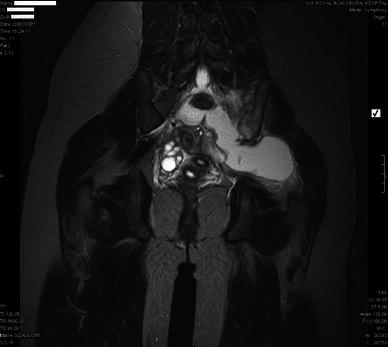

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) confirmed the cystic nature of the lesion shown on the plain X-ray (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of the left ankle of Patient A illustrating the cystic lesion in the talus bone

The fluid from the lesion in the talus was aspirated in the operating theatre and this was sent for standard microscopy, culture and sensitivity. The Gram’s stain did not yield any evidence of organisms and the subsequent standard culture of the sample was sterile. As TB was then suspected, a bone biopsy of the talar lesion was performed and sent for acid fast bacilli (AFB) analysis and histological investigation. No AFBs were seen on microscopy, but the histopathologist’s report detailed the presence of caseating granuloma formation consistent with the diagnosis of infection with Mycobacterium species. Plain chest films did not reveal any signs of pulmonary TB. A tuberculin purified protein derivative (PPD) test was performed, but the reaction at the site of infiltration was not significant.

The child’s foot and ankle function returned to normal following a 6-month course of standard anti-TB therapy as per NICE guidelines [8].

Patient B

A 4-year-old British-born girl of Pakistani descent presented to her General Practitioner complaining of a painful right hip joint. She had complained of discomfort in the right hip joint for one month. However, it became much worse on the day of presentation. There was no history of trauma, recent infection or past medical history of note. She was afebrile at initial presentation. The only associated symptom was that of mild anorexia. There was no known TB contact, although she had spent 3 weeks in India when she was 1 year of age. The child had been given the BCG vaccination at birth.

The child was unwell with a very painful right hip and she had a temperature of 37.9°C. Secondary to pain, she was unable to tolerate any movement of the joint. Haematological and biochemical investigations revealed increased WCC of 15.2 × 109/L, neutrophils of 12.3 × 109/L and raised CRP (30 mg/L). ESR was not performed. The initial diagnosis was of an acute bacterial septic arthritis of the hip joint. An emergency arthrotomy was performed, yielding frank pus from the hip joint. The joint was then thoroughly irrigated. Subsequent Gram’s stain and standard culture of the fluid did not reveal any organisms. Analysis for TB was not requested at that time. Due to slow progress over the first week, the possibility of TB infection was considered and a further arthrotomy and harvesting of samples for TB culture was undertaken. Microscopy confirmed the presence of AFBs in the second set of samples. There were no other organisms seen in the sample cultured after 48 h of incubation. A tuberculin PPD test demonstrated a large wheal at the site of infiltration. These findings were sufficient to confirm the diagnosis of TB infection of the hip joint and appropriate anti-TB treatment was commenced [8].

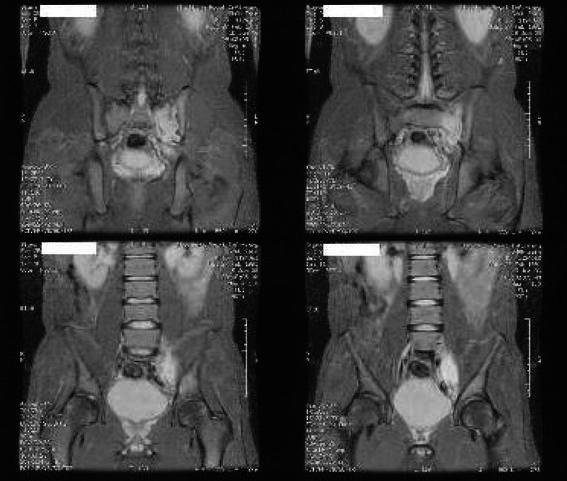

An MRI scan confirmed the presence of a small abscess within the right hip joint (Fig. 3). Plain X-rays of the chest did not reveal any evidence of pulmonary TB.

Fig. 3.

MRI scan of the pelvis of Patient B demonstrating the presence of an abscess in the region of the right hip, originating from the joint capsule, extending into the buttock

Following completion of the course of anti-TB therapy, the child’s hip movement and function returned to normal, with no complications.

Patient C

A 13-year-old British-born girl of Bangladeshi descent was referred by her General Practitioner. She presented with a history of intermittent lower back pain which had an insidious onset of 6 months. The pain did not radiate and was not relieved by paracetamol or diclofenac. There was moderate weight loss and anorexia, but no abnormal neurology or genito-urinary problems. She had no relevant medical or surgical problems prior to this episode and was of normal growth and development. The child had received the BCG vaccination in the neonatal period. There was no known TB contact, but when she was younger, she had visited Bangladesh for 3 months.

On examination, the child was found to be comfortable at rest. She was afebrile and systemic examination was unremarkable. Regional examination of the back, hips and lower limbs were normal with no abnormal neurological findings.

There was a raised ESR of 98 mm/h and an elevated CRP of 13 mg/L. The WCC was normal.

Plain X-rays of the pelvis and lumbar spine were normal. A tuberculin PPD test demonstrated a skin reaction with a wheal measuring 38 mm at the site of administration at 48 h. This supported a diagnosis of TB infection of the sacro-iliac joint. An MRI scan demonstrated a cystic lesion (described by the radiologist as a ‘cold abscess’) arising from the left sacro-iliac joint and extending into the left buttock (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

MRI scan of the pelvis of Patient C demonstrating an abscess in the region of the left sacro-iliac joint extending into the surrounding tissues

The abscess was drained by an interventional radiologist and samples were sent for TB culture. Standard anti-TB medication was commenced [8].

Microscopy showed no visible acid fast bacilli. However, TB culture did yield Mycobacterium tuberculosis sensitive to all conventional antimicrobial agents. There were no signs of TB on plain chest X-ray.

The child was discharged home on anti-TB medication. This course of therapy was completed and her symptoms resolved completely.

Patient D

A 14-year-old Pakistani born boy was referred to the paediatric department with a 3-month history of pain in the left hip. The pain was worse at night and when exercising. The child denied any previous back problems and there was no other relevant history.

The child had been born in Pakistan of Pakistani parents and moved to England at the age of 12 years. There was no known history of TB contact.

On examination, he appeared healthy and was able to weight-bear. There was localised tenderness over the left sacro-iliac joint. Examination of the spine and lower limb joints were normal. There was an elevated ESR of 30 mm/h and a mildly elevated CRP of 8 mg/L. The WCC was normal. Rheumatological tests did not reveal the presence of HLA B27, anti-nuclear factor or tissue autoantibodies. Immunoglobulins (IgA and IgG) were elevated beyond the normal range.

Plain X-ray of the pelvis demonstrated subtle erosive changes at the left sacro-iliac joint and left-sided hilar lymphadenopathy could be seen on the chest radiograph.

An MRI scan of the pelvis demonstrated a cystic lesion in the left sacro-iliac joint (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

MRI scan of the pelvis of Patient D demonstrating an abscess in the left sacro-iliac joint

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the thorax confirmed left-sided peri-hilar lymphadenopathy. The left sacro-iliac abscess was decompressed surgically and the pus was sent for TB analysis. Synovium was also obtained at that time and was sent for both TB culture and histological analysis. These samples both contained the organism M. tuberculosis sensitive to all standard anti-TB treatment and standard anti-TB therapy was commenced as per the guidelines [8]. Histological confirmation of granulomatous inflammation was seen, suggestive of infection with Mycobacteria species. A diagnosis was made of sacro-iliac TB secondary to pulmonary TB.

The child responded well to the anti-TB therapy and had no further problems.

Discussion

All of the children presented in this case series share common features; their ethnicity, the apparent absence of direct TB contact on history, elevated inflammatory markers and a generally insidious presentation.

All of the children were from the British Asian community. Sandher et al. [1] noted that 90% of all cases of bone and joint TB were in persons from the South Asian community in Blackburn, the majority of these being born abroad.

The findings of our report would suggest that the incidence of TB infection of bones and joints is increasing in children. Although this case series only details TB infection rates in bones and joints in children over a 2-year period, in the preceding 17 years, there were only two cases of bone and joint TB infection in children in the Blackburn area [1]. In 1991, the national census revealed a local South Asian population of 10.6% [9]. By 2001, the percentage had risen to 20.6% in the Blackburn and Darwen district, with 40% of this group being under the age of 15 years [10]. Blackburn and Darwen is the ninth most deprived district in England (out of 350) and has the second highest birth rate [10]. The pool of young Asian children has greatly increased over the past 10 years, and this is one possible explanation for the apparent increasing incidence of bone and joint TB infection in our area.

International travel has become commonplace over the last decade, with air travel becoming more accessible and less expensive. Each of the children reported had been born or visited the Indian subcontinent for an extended period. TB is endemic in the Indian subcontinent, and since no adult family cases were identified on contact tracing, one must assume this to be the route of infection.

There have been 2,643 cases of bone and joint TB in England, Wales and Northern Ireland between 1999 and 2006, and 77 of those have been in children aged less than 15 years [7]. The most common site for bone and joint TB in adults is the spine (accounting for almost 50% of cases [1]). Of the 11 cases of bone and joint TB in children in the 1998 survey, five had infection localised to the spine [11]. Bone and joint TB accounts for 2.4% of all TB in children and 5% of the 53,665 cases of TB in England, Wales and Northern Ireland in the 7-year period from 1999 to 2006 [7].

This series highlights the importance of being aware of the diagnosis of bone and joint TB in British Asian children and the importance of sending samples of pus, synovial fluid or joint tissue for analysis. The absence of the sequelae of pulmonary TB on chest X-ray should not rule out TB from the differential diagnosis. Teamwork and the early involvement of microbiologists, paediatricians, pathologists, TB specialists and orthopaedic surgeons is imperative for the prompt diagnosis and early treatment of this potentially serious condition.

References

- 1.Sandher DS, Al-Jibury M, Paton RW, Ormerod LP. Bone and joint tuberculosis: cases in Blackburn between 1988 and 2005. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89:1379–1381. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.89B10.18943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Health Protection Agency, March 2008. Tuberculosis update. Available online at: http://www.hpa.org.uk/web/HPAwebFile/HPAweb_C/1207035533566

- 3.Health Protection Agency. Enhanced tuberculosis surveillance in England, Wales and Northern Ireland (ETS); available online at: http://www.hpa.org.uk/HPA/Topics/InfectiousDiseases/InfectionsAZ/1204100447380/#ETS. Enhanced surveillance of mycobacterial infections in Scotland (ESMI); available online at: http://www.hps.scot.nhs.uk/resp/ssdetail.aspx?id=15

- 4.Health Protection Agency. Focus on tuberculosis: annual surveillance report—England, Wales and Northern Ireland: 2006. Available online at: http://www.hpa.org.uk/webw/HPAweb&HPAwebStandard/HPAweb_C/1204100457150?p=1249920576104

- 5.Health Protection Agency, November 2007. Tuberculosis in the UK. Annual report on tuberculosis surveillance and control in the UK 2007. Available online at: http://www.hpa.org.uk/webw/HPAweb&HPAwebStandard/HPAweb_C/1204100459636?p=1249920576104

- 6.Health Protection Agency, 2007. Annual surveillance report for tuberculosis, 2007. North West Region. Available online at: http://www.hpa.org.uk/web/HPAwebFile/HPAweb_C/1237797271526

- 7.Health Protection Agency. Enhanced tuberculosis surveillance data (personal communication)

- 8.National Collaborating Centre for Chronic Conditions for the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) (2006) Tuberculosis. Clinical diagnosis and management of tuberculosis, and measures for its prevention and control. Royal College of Physicians of London. ISBN 1860162270. Available online at: http://www.nice.org.uk/CG33

- 9.Office for National Statistics. Census data 1991. Home page at: http://www.ons.gov.uk/census/index.html

- 10.Office for National Statistics. Census data 2001. Home page at: http://www.ons.gov.uk/census/index.html

- 11.Balasegaram S, Watson JM, Rose AMC, Charlett A, Nunn AJ, Rushdy A, Leese J, Ormerod LP. A decade of change: tuberculosis in England and Wales 1988–98. Report on the behalf of the Public Health Library Service/British Thoracic Society/Department of Health Collaborative Group. Arch Dis Child. 2003;88:772–777. doi: 10.1136/adc.88.9.772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]