Abstract

Eight Beagle dogs were anesthetized and were imaged using a single channel helical CT scanner. The contrast medium used in this study was iohexol (300 mg I/ml) and doses were 0.5 ml/kg for a cine scan, 3 ml/kg for an enhanced scan. The flow rate for contrast material administration was 2 ml/sec for all scans. This study was divided into three steps, with unenhanced, cine and enhanced scans. The enhanced scan was subdivided into the arterial phase and the venous phase. All of the enhanced scans were reconstructed in 1 mm intervals and the scans were interpreted by the use of reformatted images, a cross sectional histogram, maximum intensity projection and shaded surface display. For the cine scans, optimal times were a 9-sec delay time post IV injection in the arterial phase, and an 18-sec delay time post IV injection in the venous phase. A nine-sec delay time was acceptable for the imaging of the canine hepatic arteries by CT angiography. After completion of arterial phase scanning, venous structures of the liver were well visualized as seen on the venous phase.

Keywords: angiography, computed tomography, dual phase, liver vasculature, three-dimensional image

Introduction

Computed tomography angiography (CTA) is a simple and noninvasive procedure for the evaluation of the hepatic vasculature. Although conventional angiography can also provide assessment of the hepatic vasculature, the modality is invasive and more technically difficult to perform than CTA. CTA is replacing conventional angiography in the depiction of the normal vascular anatomy and the diagnosis of vascular disorders [10]. However, CTA two-dimensional (2D) images do not provide complete three-dimensional images of the hepatic vascular anatomy. As three-dimensional (3D) reconstruction provides more comprehensive and accurate anatomic information, 3D CTA is a useful method to improve the limitations of the use of 2D images.

Three-dimensional CTA represents an increasingly important clinical tool that is used to diagnose portal hypertension and hepatic vascular disorders. These disorders include the presence of a single or multiple extrahepatic portosystemic shunt, intrahepatic portosystemic shunt, portal vein thrombosis, intravascular tumor extension, and well-developed vascular tumors such as a hepatocellular carcinoma, liver or pancreatic neoplasia. Three-dimensional CTA is also used to evaluate suspected liver disease, and is used for surgical planning [1,3,9,11].

In veterinary medicine, CT portography has been performed in normal dogs and in veterinary subjects with portosystemic shunts [3] to develop the dual-phase CT angiography technique for normal dogs [11]. However, methods of 3D reconstruction and 3D CTA analysis for the canine hepatic vasculature have not been investigated. The objectives of this study are 1) to develop the CTA technique for imaging of the canine hepatic vasculature and 2) to describe the anatomy of the hepatic vasculature with the use of 3D CTA.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Eight healthy Beagle dogs, ranging from 1 to 4 years old and weighing 6 to 12 kg were used in the study. A 22 G indwelling catheter was placed in a cephalic vein and was connected to a CT power injector (LF CT9000 ADV; Liebel-Flarsheim, USA) by an extension line (Control pressure line; Hyup Sung Medical, Korea).

Contrast media

Non-ionic iodine contrast media, iohexol (Omnipaque 300 mg Iodine/ml; Amersham Health, UK) was used for cine scans and for enhanced scans. Contrast media was injected by the use of a CT power injector and all injection rates were 2.0 ml/sec.

Helical CT scaning and parameters

CT angiography was performed using a single slice helical CT scanner (GE CT/e; GE Healthcare, USA). The CT programs for image analysis were as follows. 1) The use of cine CT; 2) the use of a retrospective reconstruction program; 3) the use of a reformatted program (for axial, sagittal, transverse and oblique plane images); 4) the use of a cross section histogram for measurement of Hounsfield units (HU) in the 2D plane; 5) the use of a 3D display of shaded surface display (SSD) and maximum intensity projection (MIP).

Experimental animal preparation for CT scanning

General anesthesia was performed to avoid motion artifacts and breath holding was induced by hyperventilation. The position of the animals was dorsal recumbency and the heads of the dogs were placed toward the CT gantry.

Experimental design

Unenhanced scan: Unenhanced scans were performed to determine the location of the cine scan, the scan field range of the enhanced scan and to measure pre-contrast HU values of the aorta (AO), caudal vena cava (CVC), portal vein (PV) and liver. Conditions included a 5 mm thickness, 3 mm interval, 1.5 pitch, 120 kVp and 40~60 mA in each animal. Scans were started from the cranial aspect of the diaphragm to the caudal aspect of the fourth lumbar vertebra. After the unenhanced scan was performed, the cine scan location, scan field range of the enhanced scan and pre-contrast HU values of each vessel and the liver at the cine scan location were determined.

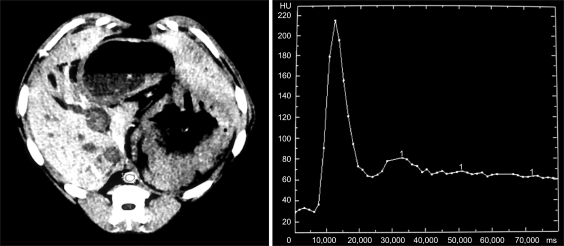

Cine scan: In the cine scan, operating conditions of a 3 mm thickness, 120 kVp, 30~55 mA, 1.5 sec per rotation scan speed and 50 serial axial images for 78 sec were performed. The cine scan was performed at the site of the well visualized AO, CVC, PV and liver at the thirteenth thoracic vertebra level. This scan was performed in order to obtain time-attenuation curves of the injected iohexol (0.5 ml/kg). With the use of time-attenuation curves, the delay time for helical CT acquisition was obtained. Time-attenuation curves of the AO, CVC and PV were achieved by using a hardwired basic CT program on the CT unit (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

A time-attenuation graph. On cine scan images, the region of interest (ROI) was set up in the center of the aorta, and then a time-attenuation graph was constructed from the ROI.

Enhanced scan: The enhanced scan was divided into the arterial phase and the venous phase. Arterial phase images were obtained by caudocranial data acquisition and venous phase images were obtained by craniocaudal acquisition to minimize time during the dual phase scan. The enhanced scan was performed by using the following parameters of a 5 mm thickness, 5 mm interval, 120 kVp, 40~60 mA and 1.3~1.5 pitch. Time-attenuation data were used to optimize the delay of CTA image acquisition following IV injection of contrast medium to maximize hepatic vessel opacification. A delay time was applied to arterial phase scanning. The venous phase was started directly after the arterial phase scan termination. The contrast medium dose used was 3 ml/kg. All enhanced phase data were reconstructed to 1 mm interval images retrospectively.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by the use of SPSS software (SPSS 12.0.0; SPSS, Chicago, IL USA). A one-way ANOVA least significant difference test was applied for quantitative data analysis. The Kruskal-Wallis test and Mann-Whitney U test were applied for qualitative data analysis [1,2].

Results

Pre-contrast HU

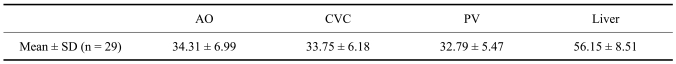

With the use of unenhanced scan images, the HU values of the AO, CVC, PV, and liver were measured in the determined cine scan location (Table 1). Regions of interest (ROI) were set at above 80% of the vascular diameter in the center of the vessels but not outside of the vessel outline. In the liver, the ROI was placed in the liver parenchyma while avoiding vessels.

Table 1.

Pre-contrast Hounsfield unit values of the aorta (AO), caudal vena cava (CVC), portal vein (PV) and liver

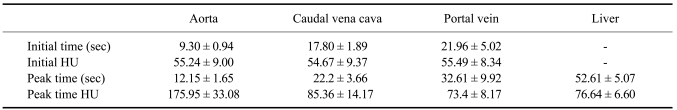

Time-attenuation curves

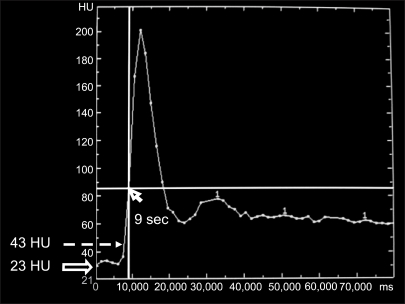

Time-attenuation data were used to optimize the delay time of the CTA image acquisition following IV injection of contrast medium to maximize hepatic vessel opacification. The time delay required for subsequent scans was defined as the time post-onset of contrast administration to the rise in the vessel HU as compared to the baseline HU plus 20 (Fig. 2). This delay time was applied to the enhanced scans. The delay time of the arterial phase was set at 9 sec (Table 2). As the initial times were so close between the CVC and PV that were approximately 18 sec and 22 sec, the delay time of the venous phase was set at 18 sec of the initial time of the CVC.

Fig. 2.

The delay time was confirmed in the aorta through a time-attenuation graph. The threshold (dash arrow) was baseline Hounsfield unit value (open arrow) added on 20 Hounsfield unit (HU). The delay time (arrow) was the first time that exceeded over this threshold.

Table 2.

Initial and peak intensifying time and Hounsfield unit (HU) values

n = 29, Contrast media dose = 0.5 ml/kg, psi = 47.44 ± 14.34. All data represent mean ± SD.

Delay time and enhanced scan periods: In the enhanced scan, the arterial phase scan was started after applying the delay time, and the venous phase scan was started immediately after termination of the arterial phase. The total enhanced scanning time was approximately 67 sec. The consumed scan-time was recorded at each phase (Table 3).

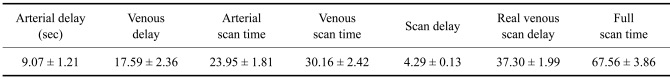

Table 3.

Delay time and consumed scan time of the enhanced scan

n = 29. All data represent mean ± SD.

3D reconstruction: Vascular 3D mapping was performed by use of a hardwired basic CT program on the CT unit. 3D SSD reconstruction was applied to a threshold-based reconstruction technique. The procedure of the threshold-based reconstruction technique is that the 3D threshold is increased in order to select opacified vessels. After applying the 3D threshold, the 3D vascular structure was seen and the background with low HU value was eliminated. With the use of 3D reconstruction, reformatted and MIP images, the anatomical location of each vessel was confirmed (Figs. 3 and 4).

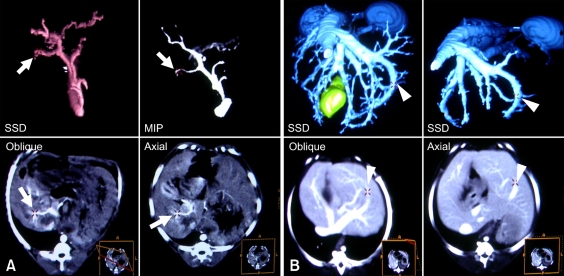

Fig. 3.

Each vessel was confirmed anatomical location through shaded surface display (SSD), maximum intensity projection (MIP), axial and oblique images (A and B). Rt. hepatic a. branch (arrows), Lt. Lateral hepatic vein (arrowheads).

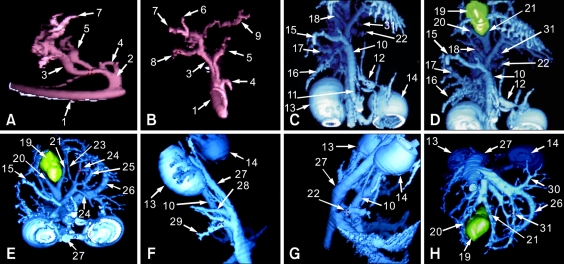

Fig. 4.

Hepatic vascular structures in three-dimensional (3D) shaded surface display images (A-H). Figs. A and B are arterial 3D structures. Figs. C-H are portal and hepatic venous 3D structures (1 = aorta; 2 = celiac a.; 3 = hepatic a.; 4 = cranial mesenteric a.; 5 = left gastric a.; 6 = right gastric a.; 7 = gastroduodenal a.; 8 = right hepatic a. branch; 9 = left hepatic a. branch; 10 = main portal v.; 11 = cranial mesenteric v.; 12 = caudal mesenteric v.; 13 = right kidney; 14 = left kidney; 15 = gastroduodenal v.; 16 = caudate portal v.; 17 = right lateral portal v.; 18 = right medial portal v.; 19 = gall bladder; 20 = right medial hepatic v.; 21 = quadrate hepatic v.; 22 = papillary hepatic v.; 23 = quadrate portal v.; 24 = left medial portal v.; 25 = left lateral portal v.; 26 = left lateral hepatic v.; 27 = caudal vena cava; 28 = caudate hepatic v.; 29 = right lateral hepatic v.; 30 = left medial hepatic v.; 31 = papillary portal v.).

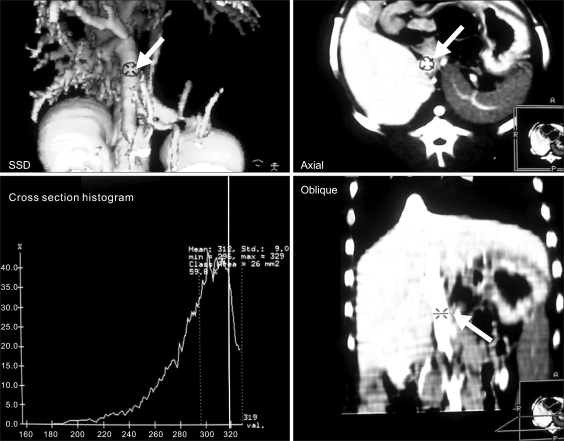

Quantitative measurement: With the use of a cross section histogram (Fig. 5), the AO, CVC and PV were measured by phases of the enhanced scans (Tables 4-6).

Fig. 5.

Average pixel intensity values were measured by defined area (arrows).

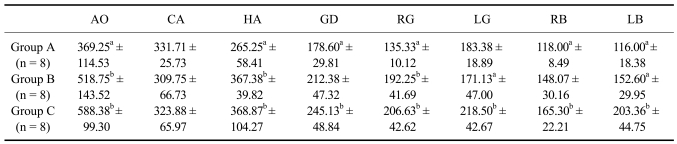

Table 4.

Hounsfield unit values of the arteries as measured in the arterial phase

a,bThere is statistical significance between a and b within columns (p < 0.05). All data represent mean ± SD. Group A = 2 ml/kg; Group B = 3 ml/kg; Group C = 4 ml/kg. AO = aorta; CA = celiac artery; HA = hepatic artery; GD = gastroduodenal artery; RG = right gastric artery; LG = left gastric artery; RB = right hepatic artery branch; LB = left hepatic artery branch.

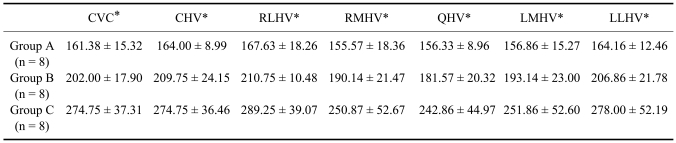

Table 6.

Hounsfield unit values of the hepatic veins in the venous phase

*There is statistical significance among groups (p < 0.05). All data represent mean ± SD. CVC = caudal vena cava; CHV = caudal hepatic vein; RLHV = right lateral hepatic vein; RMHV = right medial hepatic vein; QHV = quadrate hepatic vein; LMHV = left medial hepatic vein; LLHV = left lateral hepatic vein.

Discussion

Imaging methods for the hepatic vasculature include conventional angiography, ultrasonography, and CTA. Conventional angiography for the hepatic vasculature can provide good vascular images. However, the use of the modality is invasive to patients, has a relatively high cost as compared to other methods [6], requires a difficult technique of superselective catheterization for the hepatic arteries [8] and is time consuming. Ultrasound is an expedient method for imaging of the hepatic vasculature, but disadvantages include the disparity of accuracy between sonographers [3] and many factors such as bone, gas and fat that can interfere with the transmission of the ultrasound beam [2].

CTA provides a fast, noninvasive modality for the evaluation of the hepatic vasculature. The use of a helical CT scan with the advanced 3D display technique provides detailed anatomic images of the hepatic vasculature and requires little time. It is also less than one-third the cost of conventional angiography, and is not dependent on the skill of the operator performing the study or on the body habitus of the patient [6].

The most important parameter of the hepatic CTA was the 'time delay' between the injection of contrast medium and image acquisition. When the delay time is applied to a scan, it permits scanning during maximal enhancement. In this study, the optimal delay time was set at 9 sec in the arterial phase and at 18 sec in the venous phase. This protocol offered good vascular enhancement.

Although the venous delay time was set at 18 sec by the use of a cine scan, the actual real venous phase scan started at 20 sec later for the ideal venous delay time. This was due to the contrast medium injection delay time, the time required for arterial phase scanning and the scan delay in the CT scanner itself between arterial phase scanning and venous phase scanning. In spite of this retardation, it did not affect the image quality.

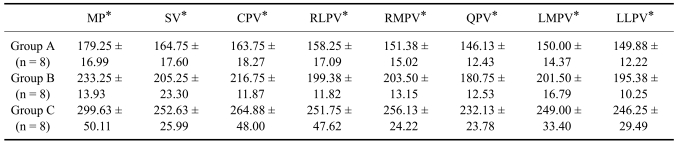

In all phases of the CT scan, vascular HU values increased as much as the contrast media dose increased. During the arterial phase, there were patterns of increasing vascular HU values, but there was no statistical difference in the HU values despite the dose increase. It was deduced that the opacified difference related to contrast dose did not appear prominent as arteries have characteristics of fast opacifying, deopacifying after contrast media injection and have a relatively smaller size than veins. In the venous phase, there were remarkable opacified differences that were seen related to contrast dosage.

In most CT angiography procedures in humans, an injection rate of various iodine concentrations is used in a range of 1.5~5 ml/sec [3]. For arterial 3D construction, 5 ml/sec is necessary to achieve a greater intravascular concentration and therefore a higher CT attenuation. Since aberrant hepatic arteries can be relatively small, they need to show sufficient enhancement so that they are not obscured during 3D threshold-based reconstruction [5]. However, in the portal and venous phase, the effect of bolus injection is gradually diminished and a higher injection rate causes a narrow "temporal window" (duration of optimal enhancement) [3]. As these factors and with a single channel helical CT limitation, although the arterial bolus effect was decreased, a rate of 2 ml/sec was chosen in this study as the injection rate.

With the use of the MIP technique, vascular anatomy is best depicted when there is a large difference between the attenuation values of vessels opacified by use of contrast agent and the surrounding tissues. However, MIP lacks depth orientation, and the technique is not as capable to display complex anatomy, especially when overlapping vessels are present [10].

Traditional helical single-slice CT scanners are still limited in the ability to image large volumes during a single breathhold and to provide adequate spatial resolution crucial for CT angiography [6]. In this study, due to the limitation of the use of a single channel helical CT scanner, a wide slice thickness and narrow scan range including the liver and the full vascular structures was used. This limitation has prompted the development of faster multidetector helical CT scanners (MDCT) that can cover an extensive volume quickly with excellent spatial resolution [6]. The use of MDCT can overcome the limitations of hepatic CTA that occur with the use of a single channel CT scanner.

In conclusion, 3D CTA has been shown as a useful method for the evaluation of the canine hepatic vasculature.

Table 5.

Hounsfield unit values of the portal veins in the venous phase

*There is statistical significance among groups (p < 0.01). All data represent mean ± SD. MP = main portal vein; SV = splenic vein; CPV = caudal portal vein; RLPV = right lateral portal vein; RMPV = right medial portal vein; QPV = quadrate portal vein; LMPV = left medial portal vein; LLPV = left lateral portal vein.

References

- 1.Awai K, Takada K, Onishi H, Hori S. Aortic and hepatic enhancement and tumor-to-liver contrast: analysis of the effect of different concentrations of contrast material at multi-detector row helical CT. Radiology. 2002;224:757–763. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2243011188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carlisle CH, Wu JX, Heath TJ. Anatomy of the portal and hepatic veins of the dog: a basis for systematic evaluation of the liver by ultrasonography. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 1995;36:227–233. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frank P, Mahaffey M, Egger C, Cornell KK. Helical computed tomographic portography in ten normal dogs and ten dogs with a portosystemic shunt. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2003;44:392–400. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8261.2003.tb00475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Han JK, Choi BI, Kim AY, Kim SJ. Contrast media in abdominal computed tomography: optimization of delivery methods. Korean J Radiol. 2001;2:28–36. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2001.2.1.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Henseler KP, Pozniak MA, Lee FT, Jr, Winter TC., 3rd Three-dimensional CT angiography of spontaneous portosystemic shunts. Radiographics. 2001;21:691–704. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.21.3.g01ma14691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Katyal S, Oliver JH, 3rd, Buck DG, Federle MP. Detection of vascular complications after liver transplantation: early experience in multislice CT angiography with volume rendering. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;175:1735–1739. doi: 10.2214/ajr.175.6.1751735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maher MM, Kalra MK, Sahani DV, Perumpillichira JJ, Rizzo S, Saini S, Mueller PR. Techniques, clinical applications and limitations of 3D reconstruction in CT of the abdomen. Korean J Radiol. 2004;5:55–67. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2004.5.1.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schmidt S, Lohse CL, Suter PF. Branching patterns of the hepatic artery in the dog: arteriographic and anatomic study. Am J Vet Res. 1980;41:1090–1097. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith PA, Klein AS, Heath DG, Chavin K, Fishman EK. Dual-phase spiral CT angiography with volumetric 3D rendering for preoperative liver transplant evaluation: preliminary observations. J comput Assist Tomogr. 1998;22:868–874. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199811000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Urban BA, Ratner LE, Fishman EK. Three-dimensional volume-rendered CT angiography of the renal arteries and veins: normal anatomy, variants, and clinical applications. Radiographics. 2001;21:373–386. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.21.2.g01mr19373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zwingenberger AL, Schwarz T. Dual-phase CT angiography of the normal canine portal and hepatic vasculature. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2004;45:117–124. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8261.2004.04019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]