Abstract

Broken chromosomes arising from DNA double strand breaks result from endogenous events such as the production of reactive oxygen species during cellular metabolism, as well as from exogenous sources such as ionizing radiation1, 2, 3. Left unrepaired or incorrectly repaired they can lead to genomic changes that may result in cell death or cancer. DNA-dependent protein kinase (DNA-PK), a holo-enzyme that comprises DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit (DNA-PKcs)4, 5 and the heterodimer Ku70/Ku80, plays a major role in non-homologous end joining (NHEJ), the main pathway in mammals used to repair double strand breaks6, 7, 8. DNA-PKcs is a serine/threonine protein kinase comprising a single polypeptide chain of 4128 amino acids and belonging to the phosphotidyl inositol 3-kinase (PI3-K)- related protein family9. DNA-PKcs is involved in the sensing and transmission of DNA damage signals to proteins such as p53, setting off events that lead to cell cycle arrest10, 11. It phosphorylates a wide range of substrates in vitro, including Ku70/Ku80, which is translocated along DNA12. Here we present the crystal structure of human DNA-PKcs at 6.6Å resolution, in which the overall fold is for the first time clearly visible. The many α-helical HEAT repeats (helix-turn-helix motifs) facilitate bending and allow the polypeptide chain to fold into a hollow circular structure. The C-terminal kinase domain is located on top of this structure and a small HEAT repeat domain that likely binds DNA is inside. The structure provides a flexible cradle to promote DNA double-strand-break repair.

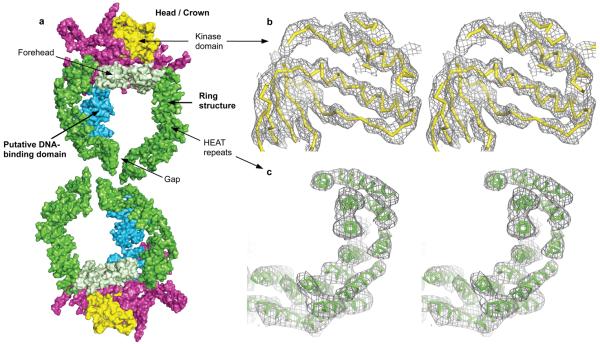

Knowledge of the 3-D structure of DNA-PKcs will enable a better understanding of its role in the events that take place in the NHEJ. However, owing to its size, crystallization of DNA-PKcs on its own or in complex with its interacting partners has proved challenging. We have now purified DNA-PKcs and complexed it with Ku80ct140 and Ku80ct194, C-terminal fragments of Ku80 of 140 and 194 amino acids respectively. The uncomplexed form and both complexes crystallized but under slightly different conditions; the complex with Ku80ct194 was used for most experiments and provides the observed structure factor amplitudes with which the electron density maps were calculated. A sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS) poly-acrylamide gel of the dissolved crystals (see Supplementary Fig. 1) confirms the presence of DNA-PKcs and the Ku80ct194 domain. The three-dimensional structure of this complex at 6.6Å was determined using phases calculated by multi-wavelength anomalous dispersion (MAD) method with the tantalum bromide heavy atom cluster (see Methods). These crystals have two molecules in the asymmetric unit (Fig. 1a). Although the electron density of most helical regions is clearly visible, the weak electron density in the loop regions connecting the helices (Fig. 1c) makes a reliable fitting of the whole polypeptide chain impossible at this resolution. Moreover, it was also not possible to locate unambiguously the Ku80ct194 fragment, which like DNA-PKcs also contains alpha-helical HEAT repeats13, 14. The structure presented here gives an overall view of the molecule.

Figure 1. Crystal structure of DNA-PKcs at 6.6Å resolution.

a) Molecular surface of the two DNA-PKcs molecules present in the asymmetric unit of the crystal that are related by the two-fold non-crystallographic symmetry. The colour-coding of the molecule is as follows: green – the ring structure; light green – the forehead that is part of the ring structure; cyan – the putative DNA-binding domain; magenta – the larger C-terminal region that carries the FAT and FATC domains; yellow – the kinase domain. Stereo diagrams of b) a representative area of SigmaA weighted 2Fo-Fc electron density map from final refinement in the kinase domain region (ribbon representation in yellow colour); c) experimental Fo electron density map calculated with phases obtained by MAD method in the area of the N-terminal HEAT repeat ring, the final DNA-PKcs model shown in green. Both electron density maps shown are contoured at 1.0 sigma level.

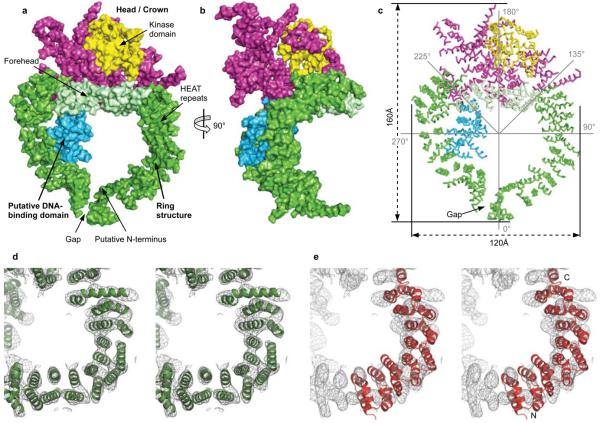

The DNA-PKcs structure, which is organized into several distinct domains (Fig. 2), measures 160Å from the top of the kinase domain to the bottom of the ring structure and the ring is about 120Å in diameter (Fig. 2c). Going anti-clockwise from the “Gap” about 66 helices are arranged as HEAT repeats in a ring structure (Fig. 2c). They are folded into a hollow circular structure, which has a concave shape rather like a cradle, when viewed from the side (Fig. 2b).

Figure 2. Overall view of the DNA-PKcs structure.

Molecular surface of the DNA-PKcs: a) front of the molecule. The colour-coding of the different parts of the molecule is as shown in figure 1a. b) Side view. c) Ribbon representation of the Cα positions of figure 2a, indicating the overall size and the sites that are potentially flexible at 135° and 225°. Stereo diagrams of d) experimental Fo electron density map in the HEAT repeat area of the ring structure with the final DNA-PKcs model shown in green; e) HEAT repeats of phosphatase 2A PR65/A subunit (residues 1 to 325; PDB accession code 1b3u) superposed onto the electron density of DNA-PKcs structure. The N- and C-termini of phosphatase 2A PR65/A subunit are shown. Both electron density maps are contoured at 1.0 sigma level.

The region that is likely to be the head/crown identified in earlier electron microscopy studies15, 16, 17, 18 is shown in yellow and magenta (Fig. 2a-c); the kinase domain can be docked into the yellow region (see below) implying that the head/crown contains the C-terminal region of DNA-PKcs. Indeed, the unequivocal positioning of the kinase domain together with the reasonably clear path of the HEAT repeats motifs, implies that the N-terminus is in the ring structure, probably at the right-hand side of “Gap” as viewed in figure 2.

HEAT repeats are also found in the phosphatase 2A PR65/A subunit19, importin–β20, cand121 and many other proteins. In DNA-PKcs the repeats are structurally irregular (Fig. 2d), making it difficult to use known structures (Fig. 2e) to guide the modeling of the HEAT repeats. Consequently, alanine helices were initially placed in the clearly visible rods of electron density using COOT22 and refined individually as rigid bodies in REFMAC23. The organization of the HEAT repeats leads to an inner and an outer layer of α-helices, giving a handedness to the overall fold of the polypeptide chain.

As noted above, the circular arrangement of the HEAT repeats has a “Gap”. Most probably the polypeptide chain has its N-terminus on one side of this “Gap”, circumnavigates the ring and then reverses direction on the other (Fig. 2a). There are some particularly irregular regions; for example, at around 135° round the ring structure from the “Gap” going anti-clockwise (Fig. 2c) and again at about 225°. The portion of the structure on the opposite side to the “Gap” in the ring structure lies between the two points of irregularity (135°-225°) and appears to be equivalent to the region identified as the forehead in electron microscopy studies18. The forehead and the residues around the “Gap” flop towards one another, giving the ring structure a concave shape or cradle appearance when viewed from the side (Fig. 2b).

The two irregular helical regions are likely equivalent to the points of conformational flexibility suggested by Spagnolo et al.24 on the basis of their electron microscopy studies. A conformational change could widen the “Gap”, a movement resembling bent arms swinging apart, so providing a mechanism for DNA-PKcs release of DNA after ligation. The release is probably triggered by one of the two major phosphorylation clusters ABCDE or PQR that are thought to control DNA end processing25. The conformational changes would likely transmit to the head/crown that carries the kinase domain. Thus, the arrangement and size of the ring structure reflects the use of this part of the structure as a platform for proteins that engage in the repair of the broken DNA and which together with Ku holds in place the DNA while it is being repaired.

After the chain reversal there is a much smaller globular domain, also organized as HEAT repeats, which represents a good candidate for DNA binding18 (Fig. 2a, shown in cyan). DNA-PKcs can bind directly to DNA and become active in the absence of Ku70/80 as demonstrated in earlier studies by electrophoretic mobility shift and atomic force microscopy studies26. This binding could take place through this domain. The region following the putative DNA binding domain and N-terminal to the kinase domain is likely to contain some of the sites that interact with other proteins. The electron density is predominantly rod like, indicating that this part is also α-helical with a number of the helices organized into HEAT repeats, a feature that is observed throughout the DNA-PKcs structure.

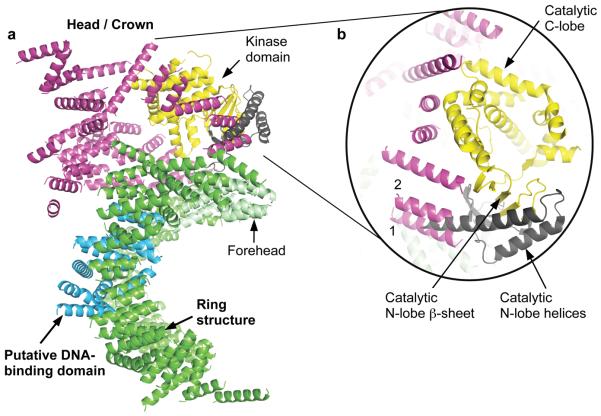

We superposed the kinase structure from PI3Kγ27 on the head/crown domain of the DNA-PKcs crystal structure, using COOT22, and obtained a convincing fit to the β-strands of the N-lobe, which fit into the flat density present, as well as the helices that dominate the C-lobe as shown in figure 3. This provides unequivocal location of the kinase in the head/crown positioned above the ring structure. The FAT domain, a region of around 500 amino acids, N-terminal to the kinase domain28, and named after the three main groups sharing this domain, FRAP, ATM and TRRAP, has been found only in PI3K- related kinases28. This family also has a much smaller, highly conserved domain at the extreme C-terminus of their sequences that is 35 residues long called FATC28, which is known to be α-helical29. These two domains are always found together and Bosotti et al.28 have proposed that the FAT and FATC domains interact with the kinase domain wedged between. This suggests that these are in the region shown in magenta with the kinase exposed at the very top accessible to substrates (Fig. 2).

Figure 3. Location of the DNA-PKcs kinase domain.

a) The overall structure of DNA-PKcs showing the location of the kinase catalytic domain (yellow). The two helices of the N-lobe are shown in brown and were not built into the final structure of DNA-PKcs due to unclear electron density in this area. The catalytic domain of DNA-PKcs was built based on the crystal structure of PI3Kγ kinase (PDB accession code: 1e8x). b) A close up view of the DNA-PKcs kinase catalytic domain. Two helices of PI3Kγ kinase N-lobe could occupy the positions of helices 1 and 2 of DNA-PKcs shown in magenta.

As noted above, the crystal structure of DNA-PKcs was defined independently of the published electron microscopy structures15, 16, 17, 18, 30, which differ quite radically between themselves. Nevertheless, our crystal structure has some features in common with the electron microscopy models, such as the head/crown as can be seen from the comparison in Supplementary Figure 2. A further example is the putative DNA binding domain, which was identified in the structure reported by Williams and co-workers18. This can be seen in the crystal structure although the base and additional openings seen in some electron microscopy structures are not observed. The absence in the crystal structure of the additional openings that were thought to play a role in binding single stranded DNA implies that both double-stranded and single-stranded DNA may bind to DNA-PKcs through the putative DNA binding domain.

Our crystal structure of DNA-PKcs brings into focus the distinct domains and their architectures and reveals irregular regions of repetitive structures where conformational changes likely take place.

Methods Summary

DNA-PKcs was isolated from HeLa S3 cells and purified using ion exchange and size exclusion chromatography. The Ku80ct194 / Ku80ct140 domains were over-expressed in E. coli strain BL21 (DE3) and purified to homogeneity from the soluble lysates in four chromatographic steps. The vapour diffusion method using PEG 8000 as a precipitant was used to crystallize DNA-PKcs in complex with Ku80ct194 and Ku80ct140. Diffraction data were collected at the European Synchrotron Radiation Source. The structure was solved using phases calculated by multi-wavelength anomalous dispersion method with the tantalum bromide heavy atom cluster.

Methods

DNA-PKcs purification

DNA-PKcs isolated from HeLa S3 cells was purified to near homogeneity using a modified protocol of Gell and Jackson31. All steps were carried out at 4°C. HeLa cells were purchased from Cancer Research UK in frozen pellet form. HeLa cell nuclear extract was prepared as described in Current Protocols in Molecular Biology32, with the protease inhibitor tablets added at the nuclear extraction stage. The prepared nuclear extract was dialysed in 20mM HEPES pH 7.6, 100mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 0.5mM EDTA, 2mM MgCl2, 5mM DTT, 0.2mM PMSF and fractionated using standard chromatographic procedures beginning with Q-sepharose followed by heparin agarose column. Fractions containing DNA-PKcs were further purified using Mono S and Mono Q ion exchange columns. DNA-PKcs was eluted from these columns using a linear gradient of 0.1 - 1M NaCl. DNA-PKcs containing fractions were dialysed in the above buffer before each step. Superose-6 gel filtration column was used as the final purification step. Protein purity was judged by SDS-PAGE. Pure DNA-PKcs used as a marker was a gift from Dr G. Smith. The purified protein was further confirmed as DNA-PKcs using mass spectrometry (proteins identified in poly-acrylamide gels) by The Protein and Nucleic Acid Chemistry Facility (PNAC) in Cambridge. Pure protein was immediately used for crystallization experiments or stored in aliquots at −80°C. All columns were purchased from Amesham Biosciences.

Ku80 C-terminal domain expression and purification

Two small Ku80 C-terminal domains spanning residues 539-732 (Ku80ct194) and 593-732 (Ku80ct140) were cloned into pGAT3 with a 6xHis-tag at the N-terminus and fused to glutathione S-transferase (GST). These were over-expressed in E. coli strain BL21(DE3) and the soluble lysates were purified to homogeneity in four chromatographic steps. In the first step, the cloned domain together with GST was isolated using Ni-NTA affinity chromatography. In the second step, the 6xHis-tag and the GST were removed using tobacco ect virus (TEV) protease. The subsequent two steps were ion exchange chromatography using a Mono-Q column with a NaCl gradient of 0 - 1 M in 20mM Tris buffer at pH 8.0 and size exclusion chromatography using Superdex-200 in 20mM Tris buffer at pH 8.0.

Crystallization

DNA-PKcs was crystallized using the vapour diffusion method in hanging drops. Extensive optimization was required to produce crystals suitable for X-ray diffraction analysis. The two buffer conditions that produced best crystals were: a) 0.1M Bis-Tris, 200mM NaCl, 5mM DTT in the presence of 8% PEG 8000 (w/v) and b) 0.1M Bis-Tris, 200mM NaCl, 30% glycerol, 10mM DTT, 5mM EDTA in the presence of 18% PEG 8000 (w/v). The pH of these buffers varied from 6.2 to 6.7. Hanging drops were prepared by mixing a 6.4 mg/ml protein sample in a 1:1 ratio with the buffer solution containing PEG 8000 used in the reservoir. Improvement in crystal quality resulted upon forming complexes of DNA-PKcs with either of two Ku80 C-terminal fragments. These were mixed in the ratio of DNA-PKcs : Ku80ct, 1:3, and crystallized using conditions described in a) and b) respectively. The crystals using conditions a) required 26% ethylene glycol for cryo-protection whilst those from b) were directly flash-frozen with 30% glycerol present in the crystallization buffer providing cryo-protection. The complex with Ku80ct194, which diffracted to 6.6Å resolution (Supplementary Table, provided) the data with which the density maps were calculated. A SDS poly-acrylamide gel of the dissolved crystals (Supplementary Fig. 1) confirms the presence of DNA-PKcs and the Ku80ct194 domain.

Heavy-metal crystal soaks

For obtaining the phasing information, the crystals were soaked in a variety of conventional heavy metal atom solutions. Of these, dodeca-μ-bromo-hexatantalum dibromide (Ta6Br122+)33 gave a deep green colour, a good indication of cluster incorporation into the crystal lattice. The soaking was carried out overnight at 1.1mM concentration of Ta6Br122+ in the crystallization buffer. The crystals were then back-soaked for an hour before flash-freezing in liquid nitrogen. These crystals were used to obtain the phase information using multi-wavelength anomalous dispersion method that led to identification of the structure of DNA-PKcs/Ku80ct194 complex.

Data collection, phasing and refinement

The diffraction data collection on Ta6 Br122+ derivative crystals was carried out at 100K using a Quantum 315R CCD area detector (Area Detector Systems Corporation) on the ID29 beamline at ESRF (Grenoble, France). X-Ray Fluorescence34 (XRF) spectroscopy confirmed the presence of tantalum atoms in the crystals. The MAD X-ray diffraction datasets were collected at the absorption peak (wavelength 1.2549Å) and at the inflection point of the Ta L3 edge (wavelength 1.2552Å). The datasets were collected from one crystal using one degree oscillation, each of the datasets had 180 degrees of data, the appropriate data collection segments were calculated using MOSFLM's STRATEGY routine35. The datasets were processed and scaled using DENZO and SCALEPACK36. The crystal belongs to monoclinic P21 spacegroup and has two molecules of DNA-PKcs/Ku80ct194 complex in the asymmetric unit resulting in crystal's solvent content of about 63%. The presence of the two molecules in the asymmetric unit was also confirmed by the presence of non-crystallographic (NCS) two-fold axis clearly visible on self-rotation function plots calculated using POLARRFN from the CCP4 program suite37.

The initial set of phases was determined by MAD method using tantalum atoms as anomalous scatterers. A total of 10 Ta6Br122+ cluster sites were identified using PHENIX's AutoSol routine38. A resolution limit of 7.1Å was used in the calculation – the highest resolution limit of the “inflection” dataset. This PHENIX's score of the solution was 75.6 and the figure merit of phases calculated by SOLVE was 0.54. Assuming the Ta6Br122+ cluster to be a single atom the positional parameters and B factors were refined using SHARP39. The phases were refined and extended from 7.1 to 6.6Å resolution by PHENIX, solvent flattening and histogram matching were carried out using DM from the CCP4 program suite37. Two-fold NCS electron density averaging was applied but did not improve the quality of the maps, probably because the electron density for one of the two molecules of DNA-PKcs/Ku-80ct194 complex in the asymmetric unit is less well defined possibly due to thermal disorder.

A structural model of DNA-PKcs was built into the electron density maps calculated at 6.6Å resolution. Highly idealized alanine α-helices of various lengths and curvatures could be fitted into the electron density maps using COOT22. The direction of α-helices was often ambiguous, although in the HEAT repeat areas, a consensus of helical directionality was sustained with helices built in one direction on the outer side of the HEAT repeat and in the opposite direction on the inner side. After the first round of rebuilding a total of 188 helices of various lengths were built (121 in one DNA-PKcs molecules and 67 the other). Close visual inspection of the electron density maps in the area of kinase domain revealed a set of 3 helices the orientation of which was similar to that of catalytic domain of PI3Kγ kinase27 (PDB accession code: 1e8x). A real space fitting of the catalytic domain of PI3Kγ kinase into the DNA-PKcs electron density positioned it exactly in the visually identified area. Using built helices of the two DNA-PKcs molecules in the asymmetric unit the two-fold NCS operator was identified using LSQMAN of the RAVE program suite40. This was then used to reconstruct the incomplete model of the second DNA-PKcs molecule in the asymmetric unit using program XPAND of the RAVE program suite40. The final model produced an R/Rfree of 52.0/53.8 % respectively, calculated against the absorption peak data set of 6.6Å resolution.

The crystallographic refinement calculations were carried out using REFMAC5 of CCP4 program suite37. Prior to the first run of the refinement all atomic B-factors of the model were set to 80Å2. A typical refinement protocol consisted of rigid body refinement procedure including the phases obtained from the MAD calculations. The rigid body groups included individual helices and no NCS restrains or constrains were used. The model was then analysed visually in COOT and the helices were trimmed down and/or rigid-body translated/rotated to fit the resulting SigmaA weighted 2Fo-Fc, Fo-Fc maps. A total of five such refinement/rebuilding stages were carried out giving the final R/Rfree values of 44.2/44.1% respectively (Supplementary Table).

Figures. All figures were generated using Pymol (pymol.sourceforge.net).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Dr Graeme Smith for providing pure DNA-PKcs that was used in the initial experiments as a marker and also for providing the DNA-PKcs and Ku70 antibodies, Dr Luca Pellegrini for help and advice at the beginning of the project and Dr Stephen Jackson for helpful discussions. We are also grateful to Dr Ruth Peat at the London Research Institute for preparing HeLa cells, Dr Len Packman for his help in identifying DNA-PKcs in poly-acrylomide gels, Prof. Nenad Ban for providing Ta6Br122+ and Dr Christoph Mueller Dieckmann at the ESRF for support during the diffraction data collection experiments. This work was funded by the Wellcome Trust and CR-UK.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information is linked to the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature. An image of SDS poly-acrylamide gel showing the presence of DNA-PKcs and Ku80ct194 in the crystals; figures comparing the Cryo-EM structures to the X-ray electron density maps of DNA-PKcs; a movie file showing the overall structure of DNA-PKcs are available in Supplementary Information.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors for the reported crystal structure have been deposited with the Protein Data Bank (PDB) under accession code 3kgv. Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Kemp LM, Sedgwick SG, Jeggo PA. X-ray sensitive mutants of Chinese hamster ovary cells defective in double-strand break rejoining. Mutat. Res. 1984;132:189–196. doi: 10.1016/0167-8817(84)90037-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zdzienicka MZ, Tran Q, van der Schans GP, Simons JWI. Characterization of an X-ray-hypersensitive mutant of V79 Chinese hamster cells. Mutat. Res. 1988;194:239–249. doi: 10.1016/0167-8817(88)90025-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Biedermann KA, Sun J, Giaccia AJ, Tosto LM, Brown JM. Scid mutation in mice confers hypersensitivity to ionizing radiation and a deficiency in DNA double-strand break repair. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1991;88:1394–1397. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.4.1394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dvir A, Stein LY, Calore BL, Dynan WS. Purification and characterization of a template associated protein kinase that phosphorylates RNA polymerase II. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:10440–10447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carter T, Vancurova I, Sun I, Lou W, DeLeon SA. DNA-activated protein kinase from HeLa cell nuclei. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1990;10:6460–6471. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.12.6460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Critchlow S, Jackson SP. DNA end-joining: from yeast to man. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1998;23:394–398. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(98)01284-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gottlieb TM, Jackson SP. The DNA-dependent protein kinase requirement for DNA ends and association with Ku antigen. Cell. 1993;72:131–142. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90057-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ma Y, Pannicke U, Schwarz K, Lieber MR. Hairpin opening and overhang processing by an Artemis/DNA-dependent protein kinase complex in nonhomologous end joining and V(D)J recombination. Cell. 2002;108:781–794. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00671-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hartley KO, et al. DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit: a relative of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and the ataxia telangiectasia gene product. Cell. 1995;82:849–856. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90482-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoekstra MF. Responses to DNA damage and regulation of cell cycle checkpoints by the ATM protein kinase family. Current Opinion in Genetics & Development. 1997;7:170–175. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(97)80125-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anderson CW. DNA damage and the DNA-activated protein kinase. Trends. Biochem. Sci. 1993;18:433–437. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(93)90144-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yoo S, Dynan WS. Geometry of a complex formed by double strand break repair proteins at a single DNA end: recruitment of DNA-PKcs induces inward translocation of Ku protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:4679–4686. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.24.4679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harris R, et al. The 3D solution structure of the C-terminal region of Ku86 (Ku86CTR) J. Mol. Biol. 2004;335:573–582. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.10.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang Z, et al. Solution structure of the C-terminal domain of Ku80 suggests important sites for protei–protein interactions. Structure. 2004;12:495–502. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chiu CY, Cary RB, Chen DJ, Peterson SR, Stewart PL. Cryo-EM imaging of the catalytic subunit of the DNA-dependent protein kinase. J. Mol. Biol. 1998;284:1075–1081. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boskovic J, et al. Visualization of DNA-induced conformational changes in the DNA repair kinase DNA-PKcs. The EMBO Journal. 2003;22:5875–5882. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rivera-Calzada A, Maman JP, Spagnolo L, Pearl LH, Llorca O. Three-dimensional structure and regulation of the DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit (DNA-PKcs) Structure. 2005;13:243–255. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williams DR, Lee K-J, Shi J, Chen DJ, Stewart PL. Cryo-EM Structure of the DNA-Dependent Protein Kinase Catalytic Subunit at Subnanometer Resolution Reveals α-Helices and Insight into DNA Binding. Structure. 2008;16:468–477. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2007.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Groves MR, Hanlon N, Turowski P, Hemmings BA, Barford D. The Structure of the Protein Phosphatase 2A PR65/A Subunit Reveals the Conformation of Its 15 Tandemly Repeated HEAT Motifs. Cell. 1999;96:99–110. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80963-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cingolani G, Petosa C, Weis K, Müller CW. Structure of importin-β bound to the IBB domain of importin-α. Nature. 1999;399:221–229. doi: 10.1038/20367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goldenberg SJ, et al. Structure of the Cand1-Cul1-Roc1 Complex Reveals Regulatory Mechanisms for the Assembly of the Multisubunit Cullin-Dependent Ubiquitin Ligases. Cell. 2004;119:517–528. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Cryst. 2004;D60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Dodson EJ. Refinement of Macromolecular Structures by the Maximum-Likelihood Method. Acta Cryst. 1997;D53:240–255. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996012255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spagnolo L, Rivera-Calzada A, Pearl LH, Llorca O. Three-dimensional structure of the human DNA-PKcs/Ku70/Ku80 complex assembled on DNA and its implications for DNA DSB repair. Mol Cell. 2006;22:511–519. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meek K, Douglas P, Cui X, Ding Q, Lees-Miller SP. trans Autophosphorylation at DNA-Dependent Protein Kinase's Two Major Autophosphorylation Site Clusters Facilitates End Processing but Not End Joining. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:3881–3890. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02366-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yaneva M, Kowalewski T, Lieber MR. Interaction of DNA-dependent protein kinase with DNA and with Ku: Biochemical and atomic force microscopy studies. EMBO J. 1997;16:5098–5112. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.16.5098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walker EH, Perisic O, Ried C, Stephens L, Williams RL. Structural insights into phosphoinositide 3-kinase catalysis and signaling. Nature. 1999;402:313–320. doi: 10.1038/46319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bosotti R, Isacchi A, Sonnhammer ELL. FAT: a novel domain in PIK-related kinases. Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 2000;25:225–227. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)01563-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dames SA, Mulet JM, Rathgeb-Szabo K, Hall MN, Grzesiek S. The Solution Structure of the FATC Domain of the Protein Kinase TOR Suggests a Role for Redox-Dependent Structural and Cellular Stability. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:20558–20564. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501116200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leuther KK, Hammarsten O, Kornberg RD, Chu G. Structure of DNA-dependent protein kinase: implications for its regulation by DNA. The EMBO Journal. 1999;18:1114–1123. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.5.1114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gell D, Jackson SP. Mapping of protein-protein interactions within the DNA-dependent protein kinase complex. Nucleic Acids Research. 1999;27:3494–3502. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.17.3494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ausubel FM, Brent R, Kingston RE, Moore DD, Seidman JG, Smith JA, Struhl K, Chanda VB, editors. Current Protocols in Molecular Biology Chapter 12, unit 12.1. John Wiley and Sons; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schneider G, Lindqvist Y. Ta6Brl4 is a Useful Cluster Compound for Isomorphous Replacement in Protein Crystallography. Acta Cryst. 1994;D50:186–190. doi: 10.1107/S0907444993009679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leonard GA, Solé VA, Beteva A, Gabadinho J, Guijarro M, McCarthy J, Marrocchelli D, Nurizzo D, McSweeney D, Mueller-Dieckmann C. Online collection and analysis of X-ray fluorescence spectra on the macromolecular crystallography beamlines of the ESRF. J. Appl. Cryst. 2009;42:333–335. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leslie AGW. Recent changes to the MOSFLM package for processing film and image plate data. Joint CCP4 + ESF-EAMCB Newsletter on Protein Crystallography. 1992;26 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 1997:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Collaborative Computational Project, Number 4 The CCP4 Suite: Programs for Protein Crystallography. Acta Cryst. 1994;D50:760–763. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Adams PD, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Hung L-W, Ioerger TR, McCoy AJ, Moriarty NW, Read RJ, Sacchettini JC, Sauter NK, Terwilliger TC. PHENIX: building new software for automated crystallographic structure determination. Acta Cryst. 2002;D58:1948–1954. doi: 10.1107/s0907444902016657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bricogne G, Vonrhein C, Flensburg C, Schiltz M, Paciorek W. Generation, representation and flow of phase information in structure determination: recent developments in and around SHARP 2.0. Acta Cryst. 2003;D59:2023–2030. doi: 10.1107/s0907444903017694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kleywegt GJ. Use of non-crystallographic symmetry in protein structure refinement. Acta Cryst. 1996;D52:842–857. doi: 10.1107/S0907444995016477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.