Abstract

The adaptor protein p66shc promotes cellular oxidative stress and apoptosis. Here, we demonstrate a novel mechanistic relationship between p66shc and the kruppel like factor-2 (KLF2) transcription factor and show that this relationship has biological relevance to p66shc-regulated cellular oxidant level, as well as KLF2-induced target gene expression. Genetic knockout of p66shc in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) stimulates activity of the core KLF2 promoter and increases KLF2 mRNA and protein expression. Similarly, shRNA-induced knockdown of p66shc increases KLF2-promoter activity in HeLa cells. The increase in KLF2-promoter activity in p66shc-knockout MEFs is dependent on a myocyte enhancing factor-2A (MEF2A)-binding sequence in the core KLF2 promoter. Short-hairpin RNA-induced knockdown of p66shc in endothelial cells also stimulates KLF2 mRNA and protein expression, as well as expression of the endothelial KLF2 target gene thrombomodulin. MEF2A protein and mRNA are more abundant in p66shc-knockout MEFs, resulting in greater occupancy of the KLF2 promoter by MEF2A. In endothelial cells, the increase in KLF2 and thrombomodulin protein by shRNA-induced decrease in p66shc expression is partly abrogated by knockdown of MEF2A. Finally, knockdown of KLF2 abolishes the decrease in the cellular reactive oxygen species hydrogen peroxide observed with knockdown of p66shc, and KLF2 overexpression suppresses cellular hydrogen peroxide levels, independent of p66shc expression. These findings illustrate a novel mechanism by which p66shc promotes cellular oxidative stress, through suppression of MEF2A expression and consequent repression of KLF2 transcription.—Kumar, A., Hoffman, T. A., DeRicco, J., Naqvi, A., Jain, M. K., Irani, K. Transcriptional repression of Kruppel like factor-2 by the adaptor protein p66shc.

Keywords: KLF2, MEF2A, reactive oxygen species, ShcA, thrombomodulin, endothelial

The mammalian ShcA proteins were first identified as adaptors that interact with the phosphorylated cytoplasmic motif of growth receptors. There are three different ShcA proteins in this class, with relative molecular masses of 46, 52, and 66. They all have a proline-rich collagen homology domain, a Src-homology domain, and a phosphotyrosine-binding domain (1). ShcA proteins are typically known to transduce mitogenic signals from receptor tyrosine kinases to extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERKs)/mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) (2). Whereas p46 and p52shc are important for extracellular ligand/integrin-induced activation of Ras, p66shc inhibits Ras signaling and most importantly modulates intracellular redox balance by increasing cellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels (3). Reduced production of ROS in p66shc−/− cells has been associated with resistance to apoptosis mediated by a variety of signals, including hydrogen peroxide, growth-factor deprivation, and UV radiation (3,4,5). Notably, proapoptotic stimuli also lead to serine 36 phosphorylation of p66shc (6). p66shc mediates many phenotypes in a variety of cell types, including the negative regulation of T-cell activation and survival (5), suppression of nitric oxide (NO) production and endothelial-dependent vasorelaxation (7), and promotion of tumor angiogenesis by stimulating VEGF expression (8). Furthermore, mice without p66shc have a prolonged life span, consistent with its role in promoting oxidative stress (6). In addition, p66shc null mice are resistant to atherogenesis induced by a high-fat diet (9) and to oxidative stress caused by diabetes (10).

Kruppel-like factors (KLFs) are a subclass of the zinc-finger family of transcription factors characterized by the DNA-binding domain containing the conserved sequence CX2CX3FX5LX2HX3H (where X is any amino acid; underscored cysteine and histidine residues coordinate zinc) (11). Previous studies demonstrate that KLF proteins typically regulate critical aspects of cellular growth and differentiation. For example, KLF1/EKLF is essential for red blood cell maturation, whereas KLF4 regulates the differentiation and maturation of dermal and gastrointestinal epithelial cells (12, 13). Lung Kruppel-like factor (LKLF)/KLF2 is highly expressed in lungs but also present in erythroid and lymphoid cells and in the vascular endothelium (14). Expression of KLF2 is developmentally regulated (15), and global deletion of KLF2 is embryonically lethal because of impaired blood vessel maturation (16, 17). Targeted deletion of KLF2 in T cells revealed that KLF2 is involved in maintaining T-cell quiescence (14). In endothelial cells, KLF2 expression is up-regulated by flow (laminar shear stress) and inhibited by proinflammatory cytokines (18, 19). Forced expression of KLF2 in endothelial cells results in an induction of endothelial specific nitric oxide (eNOS) and thrombomodulin (TM) expression, while abrogating cytokine-mediated activation of vascular cell adhesion molecule (VCAM-1) and tissue factor (TF) (20, 21). Further, KLF2 has also been proven to inhibit endothelial cell migration and angiogenesis that were partly attributed to its ability to inhibit VEGF receptor, VEGFR2/ KDR (21). KLF2 also protects endothelial cells from oxidative stress-mediated injury and subsequently apoptosis (19). In adipocytes, KLF2 inhibits adipogenesis by regulating peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPAR-γ) expression (22).

Because of the contrasting phenotypes induced by p66shc and KLF2, particularly in vascular endothelial cells and vasculogenesis, we hypothesized that p66shc may exert some of its effects by negatively regulating the expression of KLF2. In this study, we tested this hypothesis by examining the regulation of KLF2, as well as KLF2 target transcripts, by p66shc. In addition, we examined the role of KLF2 in mediating p66shc-regulated cellular ROS.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and reagents

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were obtained from Cambrex Co. (Baltimore, MD, USA). Human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). The p65- and p50-null mouse embryo fibroblasts (MEFs) were a kind gift from Dr. Alexander Hoffmann (California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA, USA) with permission from Dr. David Baltimore and were maintained in DMEM. The p66shc wild-type (WT) and p66shc-null MEFs were a gift from Dr. T. Finkel (National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). Antibodies recognizing MEF2A (C-21), β-actin, and thrombomodulin were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA); anti-Shc from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA, USA); and anti-KLF2 was a kind gift of Dr. Huck Hui Ng (Genome Institute of Singapore, Singapore). Ad-LacZ, p66shcRNAi, and Ad-KLF2 adenoviruses have been described previously (7, 20). Full-length and all deletion constructs of the KLF2 promoter have been described previously (18).

Transient transfection reporter assays

Cells were plated at a density of 5 × 104/well in 24-well plates 1 d before transfection. Transient transfection was performed using lipofectamine (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to instructions of the manufacturer. A total of 1–2 μg of plasmid DNA was used in transfections, and total DNA was always kept constant. Renilla DNA was used as an internal control. Cells were harvested 24 h after transfection, assayed for luciferase activity, and normalized to Renilla values in each sample. All transfections were performed in triplicate for ≥3 independent experiments.

Immunoblotting

Protein lysates were boiled in SDS-PAGE gel loading buffer, subjected to SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose filter, and probed with the specified primary antibody and the appropriate peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Chemiluminescent signal was developed using Super Signal West Femto substrate (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA), blots were imaged with a Gel Doc 2000 Chemi Doc system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA), and bands were quantified using Quantity One software (Bio-Rad).

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs)

EMSAs were performed as described previously (18). Approximately 5 μg of the nuclear extract was used for the gel shift assay. A MEF2 binding site from the KLF2 promoter was included, using the following oligonucleotides: MEF2 WT, CCAGGCTTATATACCGCGGCTAAATTTAGGCTGAGCCCGGA; and mutant, CCAGGCTTATATACCGCGGCTAtcggTAGGCTGAGCCCGGA.

Briefly, nuclear extract was incubated with labeled WT oligonucleotide for 30 min. Anti-MEF2 or competitor oligonucleotides were preincubated with nuclear extract for the super shift and the competition. Complex was separated on 6% nondenaturing native gel, dried, and exposed for autoradiography.

siRNA transfection

Human MEF2-directed, p66shc-directed, or KLF2 siRNA and a nonspecific control siRNA were purchased from Invitrogen. HUVECs were plated 1 d before transfection in antibiotic-free EBM-2. On the day of transfection, specific siRNA was incubated with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) at room temperature for 30 min before adding to the HUVECs in Opti-MEM (Invitrogen). Five hours later, the medium was replaced by EBM-2 and cultured for an additional 48 h. Cells were harvested for RNA, as well as for protein. RNA expression was confirmed by real-time RT-PCR and protein expression by immunoblotting.

Real-time RT-PCR

Total RNA from cultured cells was isolated by the TRIzol (Invitrogen) method. Real-time PCR was performed using the Prism 7000 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) with the SuperScript III Platinum SYBR Green One-Step qRT-PCR Kit (Invitrogen). The following primers were used: hKLF2 (forward) 5′-tgcggcaagacctacaccaagagt-3′, (reverse) 5′-agccgcagccgtcccagtt-3′; mKLF2 (forward) 5′-accaagagctcgcacctaaa-3′, (reverse) 5′-gtggcactgaaagggtctgt-3′; hMEF2A (forward) 5′-tctagacattgagtctcactctaccc-3′, (reverse) 5′-ttctacatctgaggtccagag-3′; mMEF2A (forward) 5′-ttgagcactacagacctcacg-3′, (reverse) 5′-tgcaccagtatttccaatcaa-3′; hGAPDH (forward) 5′-ccacatcgctcagacaccat-3′, (reverse) 5′-ccaggcgcccaatacg-3′; and mGAPDH (forward) ggcaaattcaacggcacagt, (reverse) cgctcctggaagatggtgat.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays

ChIP assays were performed using a ChIP Assay Kit (Upstate, Lake Placid, NY, USA) using the indicated antibodies (18). Briefly, native protein-DNA complexes were cross-linked by treatment with 1% formaldehyde for 15 min. Equal aliquots of isolated chromatin were subjected to immunoprecipitation with indicated antibodies. The DNA associated with specific immunoprecipitates or with negative control mouse IgG was isolated and used as a template for the PCR to amplify the promoter sequences containing the pertinent binding site. Primers (forward, 5′-gcagtccgggctcccgcagtag-3′; reverse, 5′-cttataggcgcggcaggcac-3′) were used to amplify a 160-bp fragment of mouse genomic DNA that encompasses the putative MEF2-binding element in the KLF2 promoter. Primers for mGAPDH (forward, ggcaaattcaacggcacagt; reverse, cgctcctggaagatggtgat) were used as a negative control.

Measurement of cellular H2O2

Level of H2O2 was quantified in conditioned mediu using the Amplex red assay (Invitrogen), as described previously (23), according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

RESULTS

p66shc negatively regulates KLF2 expression at the transcriptional level

To determine whether p66shc regulates KLF2, we first compared KLF2 expression in a p66shc-null MEF cell line (p66shc−/− MEFs) and its isogenic p66shc+/+ cell line (WT MEFs). KLF2 expression, both at the mRNA (Fig. 1A) and protein (Fig. 1B) level, was significantly higher in the p66shc−/− MEFs when compared to the WT MEFs, suggesting transcriptional down-regulation of KLF2 by p66shc. To confirm transcriptional down-regulation of KLF2 by p66shc, KLF2-promoter-reporter activity was then measured and compared in p66shc−/− and WT MEFs. Activity of the basal 1659-bp mouse KLF2 promoter was significantly higher in p66shc−/− MEFs when compared to WT MEFs (Fig. 1C). To further demonstrate the role of endogenous p66shc in down-regulation of KLF2 expression, p66shc expression was knocked down in HUVECs with siRNA. Down-regulation of p66shc expression in HUVECs was accompanied by up-regulation of KLF2 expression at the mRNA and protein levels (Fig. 2A, B). Moreover, knockdown of p66shc in HUVECs also led to induction of TM, a KLF2 target gene in endothelial cells, at the RNA (Fig. 2C) and protein (Fig. 2B) levels. Consistent with the expression data, knockdown of endogenous p66shc expression increased basal KLF2-promoter activity in HeLa cells (Fig. 2D). These data show an inverse relationship between p66shc and KLF2 expression, suggesting that p66shc suppresses KLF2 expression at the transcriptional level.

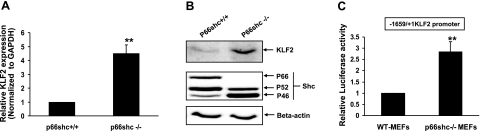

Figure 1.

p66shc deficiency increases KLF2 expression. Genetic deficiency of p66shc increases KLF2-promoter activity and KLF2 expression. KLF2 mRNA (A), protein (B), and reporter activity (C) were compared in p66shc+/+ and −/− MEFs. Normalized mRNA expression and luciferase values are shown relative to p66shc+/+ MEFs. **P < 0.01. Representative immunoblots are shown.

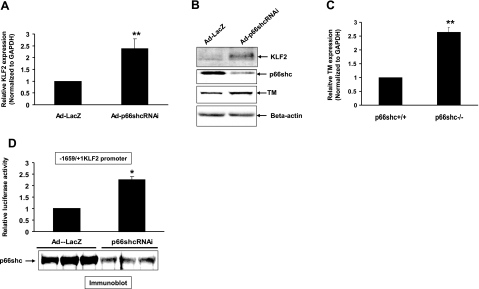

Figure 2.

p66shc regulates KLF2 in endothelial cells. Knockdown of endogenous p66shc in HUVECs increases expression of KLF2 and TM. A–C) Expression of KLF2 (A, B) and TM (B, C) at the RNA and protein levels was measured in HUVECs in which endogenous p66shc expression was adenovirally knocked down with p66shc shRNA (Adp66shcRNAi). Normalized mRNA expression values are shown relative to cells infected with the control AdLacZ virus. Representative immunoblots are shown. D) KLF2-promoter activity was measured in HeLa cells following adenoviral inhibition of endogenous p66shc. Normalized luciferase activities are shown compared to Ad-LacZ infected cells. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

Transcriptional regulation of KLF2 by p66shc is nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) independent

p66shc plays a crucial role in the regulation of intracellular reduction-oxidation (redox) state (6). Activity of the pleiotropic transcription factor NF-κB is sensitive to the redox state of the cell (24). Given the importance of NF-κB in regulating KLF2 expression by cytokines (18), we examined the role of NF-κB in p66shc-induced down-regulation of KLF2. Examination of the core KLF2-promoter sequence reveals 4 putative NF-κB sites; the importance of these NF-κB sites in p66shc-induced down-regulation of KLF2-promoter activity was investigated. Deletion mutants of KLF2 promoter that included 3, 2, 1, and 0 of these NF-κB sites were constructed. Comparison of the activities of these promoters in p66shc−/− and WT MEFs showed that, similar to the full-length core promoter (encompassing all 4 putative NF-κB sites), all truncated promoters displayed a similar difference in activity between p66shc−/− and WT MEFs (Fig. 3A) This finding suggests that none of the putative NF-κB binding sites in the core KLF2 promoter play a part in p66shc-induced suppression of promoter activity. To further confirm this finding, we examined the effect of p66shc knockdown on KLF2 expression in cells that were genetically deleted of either p65 (Rel A) or p50, components of NF-κB heterodimer. Knockdown of p66shc led to the same magnitude of KLF2-promoter induction in both p65-null and p50-null MEFs, when compared to their respective isogenic p65+/+ and p50+/+ MEF cell lines (Fig. 3B). p66shc expression was knocked down to the same extent in all cell lines (Fig. 3C). Taken together, these observations suggest that p66shc-induced down-regulation of KLF2 transcription is not mediated by NF-κB.

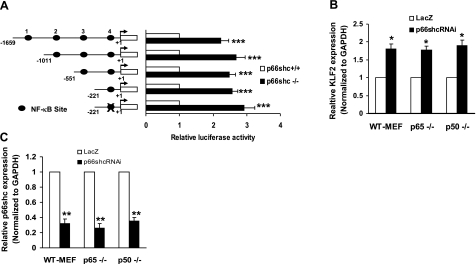

Figure 3.

p66shc-mediated regulation of KLF2 is NF-κB independent. A) Deletion analysis of KLF2 promoter. Transient transfection studies were performed using serial deletion constructs of KLF2 promoter in p66shc+/+ and p66shc−/− MEFs. Luciferase values are shown relative to p66shc+/+ MEFs. B, C) Inhibition of p66shc in p65−/− and p50−/− MEFs increases KLF2 expression. KLF2 (B) and p66shc (C) mRNA expression was measured in p50−/−, p65−/−, and WT MEFs following adenoviral knockdown of p66shc. Normalized RNA expression is shown relative to cells infected with control AdLacZ virus. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

p66shc-mediated regulation of KLF2 is dependent on MEF2A

The core 221-bp KLF2-promoter region is highly conserved in mouse and human and has a MEF-2 binding site, which plays a critical role in regulation of KLF2 expression mediated by flow (19), cytokines (18), and statins (25, 26). Because our studies suggested that this core 221 bp of the promoter is sufficient for p66shc-stimulated down-regulation of KLF2 transcription, we narrowed our focus to the MEF-2 regulatory sequence in this core promoter (19). The importance of this MEF-2 sequence in p66shc-mediated down-regulation of KLF2-promoter activity was examined. Key nucleotides in the MEF-2 sequence were mutated, and the activity of the mutated KLF2 promoter was measured in p66shc−/− and WT MEFs, and compared to the WT KLF2 promoter. In contrast to the WT KLF2 promoter, the KLF2 promoter that was mutated at the MEF-2 sequence showed a significantly lesser difference in activity between the p66shc−/− and WT MEFs (Fig. 4A), suggesting that up-regulation of KLF2-promoter activity with genetic knockout of p66shc is MEF-2-mediated. In recent years, MEF2A and MEF2C have received considerable attention in endothelial cell biology. Moreover, regulation of KLF2 by various stimuli has been known to involve MEF2A (18, 19, 25). Therefore, we focused on MEF2A for p66shc-mediated regulation of KLF2. To further investigate a specific role of a MEF2A-mediated mechanism for down-regulation of KLF2 by p66shc, binding of MEF2A to the core KLF2 promoter was compared in p66shc−/− and WT MEFs. EMSAs using lysates of p66shc−/− MEFs showed more MEF2A bound to an oligonucleotide corresponding to the MEF2A site in the KLF2 promoter, when compared to lysates of WT-MEFs (Fig. 4B). Moreover, ChIP assays demonstrated greater occupancy by MEF2A of a genomic region encompassing the MEF-2 site in the KLF2 promoter in p66shc−/− than WT MEFs (Fig. 4C), which was further validated by real-time PCR (Fig. 4D). To determine whether this increase in promoter occupancy is due to an increase in MEF2A expression, MEF2A protein and mRNA levels were compared in p66shc−/− and WT MEF. Both protein and mRNA of MEF2A were significantly higher in the p66shc−/− MEFs than in WT MEFs (Fig. 4E, F). Finally, we asked whether the increase in KLF2 and its target gene expression seen with knockdown of p66shc in endothelial cells was due to an increase in MEF2A expression. In endothelial cells, the increase in KLF2 and TM protein observed with knockdown of p66shc was at least partly reversed with concomitant knockdown of MEF2A (Fig. 4G). Collectively, these results show that endogenous p66shc down-regulates MEF2A expression, resulting in less promoter occupancy of the KLF2 promoter by MEF2A, and suggest that this down-regulation of MEF2A is responsible for the p66shc-induced decrease in KLF2 and KLF2 target gene expression.

Figure 4.

Regulation of KLF2 by p66shc requires MEF2A. A) Mutational analysis of KLF2 promoter. Normalized luciferase activity of KLF2 promoter with or without mutated MEF-2 site in p66shc+/+ and p66shc−/− MEFs. Values are presented as luciferase/Renilla ratio relative to p66shc+/+ MEFs. B) MEF2A binds KLF2 promoter. EMSA was performed by incubating oligonucleotide with sequence of MEF2 site from KLF2 promoter with equal amounts of nuclear extract from p66shc+/+ (lane 2) and p66shc−/− MEFs (lanes 3 and 4). Supershift was carried out by preincubation of nuclear extract with anti-MEF2 antibody. C) ChIP with endogenous MEF2A in p66shc−/− MEFs. ChIP assay was performed on chromatin from p66shc−/− and p66shc+/+ MEFs with MEF2A antibody (lanes 3 and 6) or nonimmune IgG (lanes 2 and 5), and a 169-bp region of KLF2 promoter encompassing MEF2 binding site was PCR amplified. Nonimmunoprecipitated chromatin was used as an input (lanes 1 and 4). PCR amplification of GAPDH promoter was used as a control. D) ChIP data were confirmed by real-time PCR. E, F) p66shc inhibition induces MEF2A expression. MEF2A RNA (E) and protein (F) were assessed in WT and p66shc−/− MEFs by real-time RT-PCR and Western blot analysis, respectively. Normalized RNA expression is shown relative to WT MEFs. **P < 0.01. G) MEF2A inhibition abrogates p66shc-mediated effect on KLF2 and TM. Expression of KLF2 (top panel) and TM (second panel) was assessed in HUVECs following siRNA-mediated inhibition of p66shc and MEF2A alone or in combination. Bottom panel: immunoblot for β-actin as a loading control. Representative blot is shown.

p66shc-mediated regulation of cellular ROS requires KLF2

Deletion of p66shc decreases cellular levels of ROS and susceptibility to oxidative stresses (27). On the basis of our observations that p66shc transcriptionally down-regulates KLF2 expression, we asked whether KLF2 plays a role in regulating cellular ROS levels. To address this, we first assessed the effect KLF2 knockdown on p66shc-mediated modulation of cellular hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) levels in endothelial cells. Adenoviral knockdown of p66shc in HUVECs led to decreased cellular H2O2 level (Fig. 5A), which was accompanied by an increase in KLF2 expression. This decrease in H2O2 induced by knockdown of p66shc was abrogated by siRNA-mediated suppression of KLF2 increase observed with p66shc knockdown (Fig. 5A). In addition, overexpression of KLF2 decreased H2O2 both in HEK 293 cells (Fig. 5B) and in HUVECs (Fig. 5C), independent of p66shc expression. These findings reinforce the reciprocal roles of p66shc and KLF2 in regulating cellular H2O2 levels and indicate that cellular oxidants stimulated by p66shc are, in part, due to p66shc-induced down-regulation of KLF2 expression.

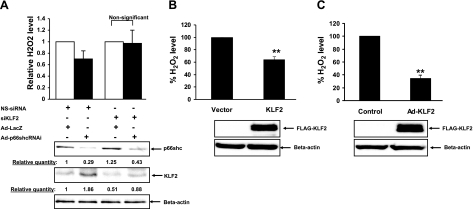

Figure 5.

Regulation of H2O2 levels in cells by p66shc involves KLF2. A) HUVECs were transiently transfected with si-KLF2 RNAi or nonspecific (NS) control RNAi. Following 24 h of transfection, cells were infected with Ad-LacZ or Ad-p66shcRNAi for an additional 48 h. H2O2 levels were assessed in conditioned media by Amplex assay. Data are presented as relative H2O2 level. Bottom panel: immunoblotting for p66shc and KLF2 expression. B) HEK 293 cells were transfected with FLAG-tagged KLF2 or empty factors. After 24 h of transfection, H2O2 levels were measured as described earlier in conditioned medium. Normalized H2O2 levels are expressed relative to KLF2 transfected or infected cells. Bottom panel: immunoblotting with FLAG antibody to detect exogenous expression of KLF2. C) HUVECs were adenovirally infected with control or Ad-FLAG-KLF2 virus. After 48 h of infection, H2O2 levels were assessed in conditioned medium as described in A. Bottom panel: immunoblotting with FLAG antibody to detect exogenous expression of KLF2. **P < 0.01.

DISCUSSION

The current paradigm suggests that p66shc plays a crucial role in oxidative-insult-related injury in a variety of cells and has significance to various pathophysiological conditions, such as diabetes, inflammation, malignancy, and aging (6, 28) (10, 29). p66shc−/− mice are resistant to oxidative stress and have an extended life span (6). p66shc impairs vascular function by inhibiting NO production (7), induces apoptosis (30), and promotes tumor angiogenesis (8). p66shc regulates cellular oxidant levels and promotes oxidative stress by several mechanisms. p66shc-mediated activation of the small GTPase rac1 plays a role in regulating cellular oxidants (23). p66shc also increases cellular H2O2 and promotes oxidative stress by suppressing expression of catalase, an antioxidant enzyme that catalyzes H2O2, and this is mediated by down-regulation of a member the Forkhead family of transcription factors (27). Moreover, a fraction of p66shc localizes to the mitochondria and regulates the mitochondrial electron transport chain and mitochondrial oxidant generation (31). Our findings suggest that down-regulation of KLF2 is another mechanism responsible for p66shc-induced increase in cellular oxidants and lead us to speculate that KLF2 down-regulation is an important phenomenon in the pathogenesis of the disease states in which p66shc plays a part. Supporting this speculation, KLF2 improves endothelial function by providing antithrombotic (26) antiadhesive, and anti- inflammatory properties to endothelium (20); inhibits angiogenesis through regulation of VEGFR2/KDR receptor (21); and protects oxidative-stress-mediated apoptosis (19).

We considered several plausible mechanisms by which p66shc may regulate KLF2 expression and promoter activity. KLF2 is transcriptionally down-regulated by a NF-κB-dependent mechanism (18). Because p66shc regulates ROS levels (32) and ROS triggers redox-sensitive signaling through regulation of several transcriptional factors, such as activator protein-1 (AP-1) and NF-κB (33), we examined the role of NF-κB in down-regulation of KLF2. Our deletion analysis of the KLF2 promoter, coupled with observations in p50- and p65-null cells, provide evidence that the NF-κB pathway is not involved in p66shc-mediated regulation of KLF2. However, NF-κB is composed of homo- and heterodimeric complexes of members of the Rel family of proteins, consisting of p65 (RelA), c-Rel, RelB, p50, and p52 (34). Therefore, we cannot completely exclude the role of other NF-κB components (c-Rel, Rel B, and p52) in down-regulation of KLF2 by p66shc.

In contrast to the lack of a role of NF-κB in mediating p66shc-induced down-regulation of KLF2 transcription, our findings indicate an important role for MEF2 in mediating this effect. In addition, our data demonstrate that MEF2 plays a part in p66shc-mediated down-regulation of the KLF2 target gene TM. MEF2 factors are members of the MADS box (MCM1, agamous, deficiens, serum response factor) family of transcription factors that comprise 4 isoforms: MEF2A, MEF2B, MEF2C, and MEF2D (35). Although best known for their role in myogenesis and in muscle development (36), an emerging literature implicates their role in various other cell types during development and differentiation. MEF2 proteins play a crucial role in cardiac development (37), vascular development (38), and neuron survival and differentiation (39, 40). Some MEF2 forms are expressed in immune cells and control selection and activation of T cells (41). MEF2 factors play an important role in the regulation of KLF2 by various stimuli. Laminar flow increases KLF2 expression through a MEF2 site in the KLF2 promoter via an ERK5-MEF2 pathway (19). Similarly, statins and cytokines require MEF2 to regulate KLF2 expression and function (18, 25). Members of the MEF2 family of transcriptional factors are themselves regulated at the level of transactivation by phosphorylation via the MAPK pathway (e.g., ERK5, p38 MAPK) (42, 43). However, recent literature also shows transcriptional regulation of the MEF2 class of genes. For example, nuclear respiratory factor-1 (NRF1) induces MEF2A transcription through the NRF1 element in the MEF2A promoter (44). In addition, MEF2A regulates its own transcription through the MEF2 element present in its promoter (44, 45). Our results showing that p66shc down-regulates MEF2A expression implicate one of the aforementioned transcriptional mechanisms in the suppression of MEF2 by p66shc.

The potential mechanisms by which KLF2 regulates cellular ROS, independent of p66shc, deserves attention. To maintain physiological homeostasis, ROS levels in cells are regulated by ROS production and removal by an antioxidant mechanism involving catalase, superoxide dismutase (SOD), and glutathione peroxidase (GPX). Interestingly, KLF2 is known to regulate some of the detoxifying enzyme to regulate ROS levels in cells. Using a gene-profiling approach, Dekker et al. (46) demonstrated that KLF2 transcriptionally up-regulates expression of catalase. Supporting this observation, overexpression of KLF2 in endothelial cell protects from hydrogen peroxide-mediated apoptosis (19).

CONCLUSIONS

The present study demonstrates a novel relationship between the adaptor protein p66shc and KLF-2, suggesting that down-regulation of KLF2 by p66shc is an important means by which the latter promotes cellular oxidants. It also adds to our current knowledge about mechanisms that regulate KLF2 target gene expression: mechanisms that may be operative in the orchestration of various cellular phenotypes, including apoptosis, and in the development of p66shc-mediated pathophysiological states, such as atherosclerosis and endothelial dysfunction.

Acknowledgments

We thank T. Finkel (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA) for the gift of the p66−/− and WT MEFs, A. Hoffmann and D. Baltimore (California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA, USA) for the p65 and p50-null MEFs, and Huck Hui Ng (Genome Institute of Singapore, Singapore) for the KLF2 antibody. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01 HL094959, R01 HL070929, and P01 HL065608 (KI), and an American Heart association BGIA 0865419D (AK).

References

- Luzi L, Confalonieri S, Di Fiore P P, Pelicci P G. Evolution of Shc functions from nematode to human. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2000;10:668–674. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(00)00146-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonfini L, Migliaccio E, Pelicci G, Lanfrancone L, Pelicci P G. Not all Shc’s roads lead to Ras. Trends Biochem Sci. 1996;21:257–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Migliaccio E, Mele S, Salcini A E, Pelicci G, Lai K M, Superti-Furga G, Pawson T, Di Fiore P P, Lanfrancone L, Pelicci P G. Opposite effects of the p52shc/p46shc and p66shc splicing isoforms on the EGF receptor-MAP kinase-fos signalling pathway. EMBO J. 1997;16:706–716. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.4.706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orsini F, Migliaccio E, Moroni M, Contursi C, Raker V A, Piccini D, Martin-Padura I, Pelliccia G, Trinei M, Bono M, Puri C, Tacchetti C, Ferrini M, Mannucci R, Nicoletti I, Lanfrancone L, Giorgio M, Pelicci P G. The life span determinant p66Shc localizes to mitochondria where it associates with mitochondrial heat shock protein 70 and regulates trans-membrane potential. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:25689–25695. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401844200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacini S, Pellegrini M, Migliaccio E, Patrussi L, Ulivieri C, Ventura A, Carraro F, Naldini A, Lanfrancone L, Pelicci P, Baldari C T. p66SHC promotes apoptosis and antagonizes mitogenic signaling in T cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:1747–1757. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.4.1747-1757.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Migliaccio E, Giorgio M, Mele S, Pelicci G, Reboldi P, Pandolfi P P, Lanfrancone L, Pelicci P G. The p66shc adaptor protein controls oxidative stress response and life span in mammals. Nature. 1999;402:309–313. doi: 10.1038/46311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamori T, White A R, Mattagajasingh I, Khanday F A, Haile A, Qi B, Jeon B H, Bugayenko A, Kasuno K, Berkowitz D E, Irani K. P66shc regulates endothelial NO production and endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation: implications for age-associated vascular dysfunction. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2005;39:992–995. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2005.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De S, Razorenova O, McCabe N P, O'Toole T, Qin J, Byzova T V. VEGF-integrin interplay controls tumor growth and vascularization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:7589–7594. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502935102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Napoli C, Martin-Padura I, de Nigris F, Giorgio M, Mansueto G, Somma P, Condorelli M, Sica G, De Rosa G, Pelicci P. Deletion of the p66Shc longevity gene reduces systemic and tissue oxidative stress, vascular cell apoptosis, and early atherogenesis in mice fed a high-fat diet. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:2112–2116. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0336359100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menini S, Amadio L, Oddi G, Ricci C, Pesce C, Pugliese F, Giorgio M, Migliaccio E, Pelicci P, Iacobini C, Pugliese G. Deletion of p66Shc longevity gene protects against experimental diabetic glomerulopathy by preventing diabetes-induced oxidative stress. Diabetes. 2006;55:1642–1650. doi: 10.2337/db05-1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bieker J J. Isolation, genomic structure, and expression of human erythroid Kruppel-like factor (EKLF) DNA Cell Biol. 1996;15:347–352. doi: 10.1089/dna.1996.15.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins A C, Sharpe A H, Orkin S H. Lethal β-thalassaemia in mice lacking the erythroid CACCC-transcription factor EKLF. Nature. 1995;375:318–322. doi: 10.1038/375318a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuez B, Michalovich D, Bygrave A, Ploemacher R, Grosveld F. Defective haematopoiesis in fetal liver resulting from inactivation of the EKLF gene. Nature. 1995;375:316–318. doi: 10.1038/375316a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo C T, Veselits M L, Leiden J M. LKLF: A transcriptional regulator of single-positive T cell quiescence and survival [see comments] Science. 1997;277:1986–1990. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5334.1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson K P, Kern C B, Crable S C, Lingrel J B. Isolation of a gene encoding a functional zinc finger protein homologous to erythroid Kruppel-like factor: identification of a new multigene family. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:5957–5965. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.11.5957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wani M A, Wert S E, Lingrel J B. Lung Kruppel-like factor, a zinc finger transcription factor, is essential for normal lung development. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:21180–21185. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.30.21180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo C T, Veselits M L, Barton K P, Lu M M, Clendenin C, Leiden J M. The LKLF transcription factor is required for normal tunica media formation and blood vessel stabilization during murine embryogenesis. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2996–3006. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.22.2996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A, Lin Z, SenBanerjee S, Jain M K. Tumor necrosis factor α-mediated reduction of KLF2 is due to inhibition of MEF2 by NF-κB and histone deacetylases. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:5893–5903. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.14.5893-5903.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parmar K M, Larman H B, Dai G, Zhang Y, Wang E T, Moorthy S N, Kratz J R, Lin Z, Jain M K, Gimbrone M A, Jr, Garcia-Cardena G. Integration of flow-dependent endothelial phenotypes by Kruppel-like factor 2. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:49–58. doi: 10.1172/JCI24787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SenBanerjee S, Lin Z, Atkins G B, Greif D M, Rao R M, Kumar A, Feinberg M W, Chen Z, Simon D I, Luscinskas F W, Michel T M, Gimbrone M A, Jr, Garcia-Cardena G, Jain M K. KLF2 is a novel transcriptional regulator of endothelial proinflammatory activation. J Exp Med. 2004;199:1305–1315. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya R, Senbanerjee S, Lin Z, Mir S, Hamik A, Wang P, Mukherjee P, Mukhopadhyay D, Jain M K. Inhibition of vascular permeability factor/vascular endothelial growth factor-mediated angiogenesis by the Kruppel-like factor KLF2. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:28848–28851. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C500200200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee S S, Feinberg M W, Watanabe M, Gray S, Haspel R L, Denkinger D J, Kawahara R, Hauner H, Jain M K. The Kruppel-like factor KLF2 inhibits peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ expression and adipogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:2581–2584. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210859200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanday F A, Santhanam L, Kasuno K, Yamamori T, Naqvi A, Dericco J, Bugayenko A, Mattagajasingh I, Disanza A, Scita G, Irani K. Sos-mediated activation of rac1 by p66shc. J Cell Biol. 2006;172:817–822. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200506001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen-Heininger Y M, Poynter M E, Baeuerle P A. Recent advances towards understanding redox mechanisms in the activation of nuclear factor κB. Free Radic Biol Med. 2000;28:1317–1327. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00218-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen-Banerjee S, Mir S, Lin Z, Hamik A, Atkins G B, Das H, Banerjee P, Kumar A, Jain M K. Kruppel-like factor 2 as a novel mediator of statin effects in endothelial cells. Circulation. 2005;112:720–726. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.525774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Z, Kumar A, SenBanerjee S, Staniszewski K, Parmar K, Vaughan D E, Gimbrone M A, Jr, Balasubramanian V, Garcia-Cardena G, Jain M K. Kruppel-like factor 2 (KLF2) regulates endothelial thrombotic function. Circ Res. 2005;96:e48–e57. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000159707.05637.a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemoto S, Finkel T. Redox regulation of forkhead proteins through a p66shc-dependent signaling pathway. Science. 2002;295:2450–2452. doi: 10.1126/science.1069004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson J G, Yoneda T, Clark G M, Yee D. Elevated levels of p66 Shc are found in breast cancer cell lines and primary tumors with high metastatic potential. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:1135–1139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veeramani S, Igawa T, Yuan T C, Lin F F, Lee M S, Lin J S, Johansson S L, Lin M F. Expression of p66(Shc) protein correlates with proliferation of human prostate cancer cells. Oncogene. 2005;24:7203–7212. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrini M, Finetti F, Petronilli V, Ulivieri C, Giusti F, Lupetti P, Giorgio M, Pelicci P G, Bernardi P, Baldari C T. p66SHC promotes T cell apoptosis by inducing mitochondrial dysfunction and impaired Ca2+ homeostasis. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:338–347. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giorgio M, Migliaccio E, Orsini F, Paolucci D, Moroni M, Contursi C, Pelliccia G, Luzi L, Minucci S, Marcaccio M, Pinton P, Rizzuto R, Bernardi P, Paolucci F, Pelicci P G. Electron transfer between cytochrome c and p66Shc generates reactive oxygen species that trigger mitochondrial apoptosis. Cell. 2005;122:221–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trinei M, Giorgio M, Cicalese A, Barozzi S, Ventura A, Migliaccio E, Milia E, Padura I M, Raker V A, Maccarana M, Petronilli V, Minucci S, Bernardi P, Lanfrancone L, Pelicci P G. A p53–p66Shc signalling pathway controls intracellular redox status, levels of oxidation-damaged DNA and oxidative stress-induced apoptosis. Oncogene. 2002;21:3872–3878. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstone S D, Fragonas J C, Jeitner T M, Hunt N H. Transcription factors as targets for oxidative signalling during lymphocyte activation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1263:114–122. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(95)00088-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayden M S, Ghosh S. Signaling to NF-κB. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2195–2224. doi: 10.1101/gad.1228704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinsey T A, Zhang C L, Olson E N. MEF2: a calcium-dependent regulator of cell division, differentiation and death. Trends Biochem Sci. 2002;27:40–47. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(01)02031-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black B L, Olson E N. Transcriptional control of muscle development by myocyte enhancer factor-2 (MEF2) proteins. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1998;14:167–196. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.14.1.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Q, Schwarz J, Bucana C, Olson E N. Control of mouse cardiac morphogenesis and myogenesis by transcription factor MEF2C. Science. 1997;276:1404–1407. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5317.1404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Q, Lu J, Yanagisawa H, Webb R, Lyons G E, Richardson J A, Olson E N. Requirement of the MADS-box transcription factor MEF2C for vascular development. Development. 1998;125:4565–4574. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.22.4565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong X, Tang X, Wiedmann M, Wang X, Peng J, Zheng D, Blair L A, Marshall J, Mao Z. Cdk5-mediated inhibition of the protective effects of transcription factor MEF2 in neurotoxicity-induced apoptosis. Neuron. 2003;38:33–46. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00191-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flavell S W, Cowan C W, Kim T K, Greer P L, Lin Y, Paradis S, Griffith E C, Hu L S, Chen C, Greenberg M E. Activity-dependent regulation of MEF2 transcription factors suppresses excitatory synapse number. Science. 2006;311:1008–1012. doi: 10.1126/science.1122511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youn H D, Sun L, Prywes R, Liu J O. Apoptosis of T cells mediated by Ca2+-induced release of the transcription factor MEF2. Science. 1999;286:790–793. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5440.790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato Y, Kravchenko V V, Tapping R I, Han J, Ulevitch R J, Lee J D. BMK1/ERK5 regulates serum-induced early gene expression through transcription factor MEF2C. EMBO J. 1997;16:7054–7066. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.23.7054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato Y, Zhao M, Morikawa A, Sugiyama T, Chakravortty D, Koide N, Yoshida T, Tapping R I, Yang Y, Yokochi T, Lee J D. Big mitogen-activated kinase regulates multiple members of the MEF2 protein family. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:18534–18540. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001573200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran B, Yu G, Gulick T. Nuclear respiratory factor 1 controls myocyte enhancer factor 2A transcription to provide a mechanism for coordinate expression of respiratory chain subunits. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:11935–11946. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707389200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran B, Yu G, Li S, Zhu B, Gulick T. Myocyte enhancer factor 2A is transcriptionally autoregulated. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:10318–10329. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707623200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekker R J, Boon R A, Rondaij M G, Kragt A, Volger O L, Elderkamp Y W, Meijers J C, Voorberg J, Pannekoek H, Horrevoets A J. KLF2 provokes a gene expression pattern that establishes functional quiescent differentiation of the endothelium. Blood. 2006;107:4354–4363. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]