Abstract

Ethanol decreases the clearance of cocaine by inhibiting the hydrolysis of cocaine to benzoylecgonine and ecgonine methyl ester by carboxylesterases, and there is a large body of literature describing this interaction as it relates to the abuse of cocaine. In this study, we describe the effect of intravenous ethanol on the pharmacokinetics of cocaine after intravenous and oral administration in the dog. The intent is to determine the effect ethanol has on metabolic hydrolysis using cocaine metabolism as a surrogate marker of carboxylesterase activity. Five dogs were administered intravenous cocaine alone, intravenous cocaine after ethanol, oral cocaine alone, and oral cocaine after ethanol on separate study days. Cocaine, benzoylecgonine, and cocaethylene concentrations were determined by high-performance liquid chromatography. Cocaine had poor systemic bioavailability with an area under the plasma concentration-time curve that was approximately 4-fold higher after intravenous than after oral administration. The coadministration of ethanol and cocaine resulted in a 23% decrease in the clearance of intravenous cocaine and a 300% increase in the bioavailability of oral cocaine. Cocaine behaves as a high extraction drug, which undergoes first-pass metabolism in the intestines and liver that is profoundly inhibited by ethanol. We infer from these results that ethanol could inhibit the hydrolysis of other drug compounds subject to hydrolysis by carboxylesterases. Indeed, there are numerous commonly prescribed drugs with significant carboxylesterase-mediated metabolism such as enalapril, lovastatin, irinotecan, clopidogrel, prasugrel, methylphenidate, meperidine, and oseltamivir that may interact with ethanol. The clinical significance of the interaction of ethanol with specific drugs subject to carboxylesterase hydrolysis is not well recognized and has not been adequately studied.

Mammalian carboxylesterases are α,β-hydrolase-fold proteins that catalyze the hydrolysis of a vast array of endogenous and exogenous esters, amides, thioesters, and carbamates (Satoh and Hosokawa, 2006). Two carboxylesterases have been identified, carboxylesterase 1 (CES1) and carboxylesterase 2 (CES2), which are primary metabolic pathways of drugs subject to catalytic hydrolysis in humans (Schwer et al., 1997; Satoh and Hosokawa 1998). The most common type of drug subject to hydrolysis in humans is an ester prodrug specifically developed to be rapidly hydrolyzed to an active metabolite after absorption from the gastrointestinal tract (Satoh and Hosokawa, 2006), but there are also drugs in which catalytic hydrolysis by carboxylesterases plays an important role in the conversion of an active drug to inactive metabolite (Zhang et al., 1999; Tang et al., 2006; Patrick et al., 2007; Farid et al., 2008). Therefore, alterations in the catalytic activity of these enzymes could play a key role in both the disposition and pharmacological actions of substrate drugs. Unlike drug-drug interactions involving the inhibition of the metabolism of agents that are substrates for the cytochrome P450 enzymes, the consequences of interactions involving inhibition of carboxylesterases have generally not been explored. The potential clinical significance of alterations in carboxylesterase activity could be important as many drugs from numerous therapeutic classes including angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, anticancer agents, opiate analgesics, HMG-CoA inhibitors, central nervous system stimulants, neuramidase inhibitors, and antiplatelet drugs are substrates.

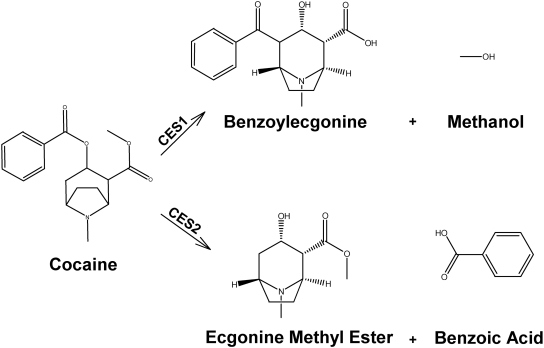

The most extensively studied drug interaction with carboxylesterases is the interaction between cocaine and ethanol. As shown in Fig. 1, cocaine is eliminated primarily by hydrolysis to benzoylecgonine (BE) and ecgonine methyl ester (EME) by CES1 and CES2 (Dean et al., 1991; Brzezinski et al., 1994; Pindel et al., 1997; Laizure et al., 2003). Ethanol has been demonstrated in vitro to inhibit both carboxylesterases (Roberts et al., 1993) and in animals and humans to inhibit the hydrolysis of cocaine to BE by CES1 (Dean et al., 1992; McCance-Katz et al., 1993; Henning et al., 1994). However, the primary focus of previous studies has been characterizing the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic interaction as it relates to the abuse of cocaine and ethanol; thus, cocaine was usually administered by nonoral routes (intravenous, intraperitoneal, smoking, and insufflation). Cocaine, which is a high-extraction drug, should demonstrate route-dependent disposition and would therefore be an excellent model substrate for the effect of ethanol on carboxylesterase-mediated hydrolysis of orally administered drugs. Because many of the therapeutic agents that are carboxylesterase substrates also undergo high first-pass, carboxylesterase-dependent metabolism, the effects of ethanol on the oral disposition of cocaine would give important insight into the magnitude and extent of drug interactions between ethanol and other drugs that undergo first-pass metabolism by these enzymes. Therefore, the objective of the present study was to use oral cocaine as a marker compound to determine the effect of ethanol-mediated inhibition of CES1 and CES2 on orally administered drugs.

Fig. 1.

The hydrolysis of cocaine by CES1 and CES2.

Materials and Methods

Animal Model.

This study was conducted in five adult, male, conditioned, mongrel dogs (weight 16–21 kg) that were part of an overall evaluation of the effects of ethanol on the pharmacokinetics and cardiovascular pharmacodynamics of cocaine. The animals underwent a 1-week training period in which they were acclimated to the laboratory and trained to stand in a nylon sling. After the training period, each animal received acepromazine (0.1 mg/kg i.m.) and atropine (0.05 mg/kg i.m.) before induction of anesthesia with thiopental (25 mg/kg i.v.). After anesthesia was induced, a cuffed endotracheal tube was placed and anesthesia was maintained with 1.5% isoflurane and oxygen. Indwelling silicone catheters (V-A-P Access Port model 6PV; Access Technologies, Skokie, IL) were implanted into the carotid artery and internal jugular vein of each animal. The catheters were tunneled subcutaneously to the back of the animal's neck and connected to a V-A-P Access Port that was sutured in place underneath the skin. The dogs received pre- and postoperative antibiotics and were allowed to recover for 7 days before studies were initiated. During the surgical recovery period, the training to stand in the nylon sling was continued. The catheters were flushed daily with heparinized saline (250 U/ml) to maintain patency. This study was approved by the University of Tennessee Animal Care and Use Committee and was performed according to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources, 1996).

Experimental Procedures.

After an overnight fast before each study day, the animals were brought to the laboratory and placed in the nylon sling. All dogs received each of the following treatments on separate study days with each treatment separated by at least 48 h: 1) 3 mg/kg i.v. cocaine; 2) 1 g/kg i.v. ethanol followed by 3 mg/kg i.v. cocaine; 3) 4 mg/kg cocaine administered orally in a gelatin capsule; and 4) 1 g/kg i.v. ethanol followed by 4 mg/kg oral cocaine. All cocaine doses are expressed in milligrams of base equivalents and given in the form of the hydrochloride salt (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) The intravenous cocaine dose was prepared in sterile 0.9% sodium chloride solution immediately before administration and infused into the jugular vein catheter over 5 min by a syringe pump (Harvard Apparatus, Natick, MA). The ethanol solution was prepared by adding absolute ethanol (McCormick Distilling Co., Weston, MO) to sterile 0.9% sodium chloride solution to give a 25% (v/v) solution that was administered over 40 min via the jugular vein catheter. We have previously demonstrated in the dog that this ethanol dose results in moderate intoxication with a mean peak concentration of 144 ± 28 mg/dl (Parker et al., 1996). Arterial blood pressure was continuously monitored using the arterial catheter connected to a Gould Statham P23Db pressure transducer via fluid-filled tubing. Blood pressure and lead II of the surface electrocardiogram were monitored and recorded using a BioPac Systems 100A recording system (BioPac Systems, Santa Barbara, CA).

Blood samples (4 ml) were collected through the arterial catheter before and at 3, 5, 7, 10, 15, 20, 25, 35, 65, 125, 185, and 365 min and 24 h after the start of the infusion. During the oral cocaine treatments, blood samples were collected before and at 10, 20, 30, 45, 60, 90, 120, 180, and 360 min and 24 h after oral cocaine administration. Blood samples were placed into chilled Vacutainer tubes (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ) containing 30 mg of sodium fluoride. Each sample was mixed gently and placed on ice immediately. Within 1 h of blood collection, plasma was separated by centrifugation for 10 min at 2000 rpm and stored at −70°C until analysis.

Plasma concentrations of cocaine, BE, and cocaethylene were determined by modification of our previously described high-performance liquid chromatography assay (Williams et al., 1996). The compounds of interest were extracted from plasma using 130-mg (3 ml) Bond Elut Certify solid-phase extraction columns (Varian Inc., Palo Alto, CA). The columns were conditioned with methanol and KH2PO4 buffer (pH 6.0). Each plasma sample containing 100 ng of the internal standard (lidocaine) was decanted onto the solid-phase extraction column, and the columns were then washed with deionized water and 100 mM HCl. The compounds were eluted with 2 ml of methanol-NH4OH (98:2), dried under nitrogen at 35°C, and reconstituted in 200 μl of mobile phase. A 170-μl aliquot was then injected onto a LC-ABZ (4.6 × 250 mm) analytical column (Supelco, Bellefont, PA) with a mobile phase of 50 mM KH2PO4 buffer (pH 5.5) and acetonitrile (84:16, v/v) at a flow rate of 1.4 ml/min with detection by UV absorbance at 230 nm.

Data Analysis.

Cocaine and BE pharmacokinetic parameters were calculated by standard noncompartmental methods using WinNonlin 3.1 (Pharsight, Mountain View, CA). Peak plasma concentrations (Cmax) were determined by direct inspection of each animal's plasma concentration-time curves. Cocaine and BE areas under the plasma concentration-time curves from time 0 to infinity (AUC0–∞) were calculated using the log-linear trapezoidal rule. The elimination rate constant (kel) was estimated by log-linear regression of the terminal portion of the plasma concentration-time curve and elimination half-life (t1/2) calculated as 0.693/kel. Cocaine bioavailability (F) was calculated as (AUCoral × Dosei.v.)/(AUCi.v. × Doseoral). A repeated-measures analysis of variance followed by Dunnett's post hoc test was used to compare the cocaine and BE pharmacokinetic parameters obtained with the oral cocaine dose with those found with oral cocaine + ethanol and intravenous cocaine treatments. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

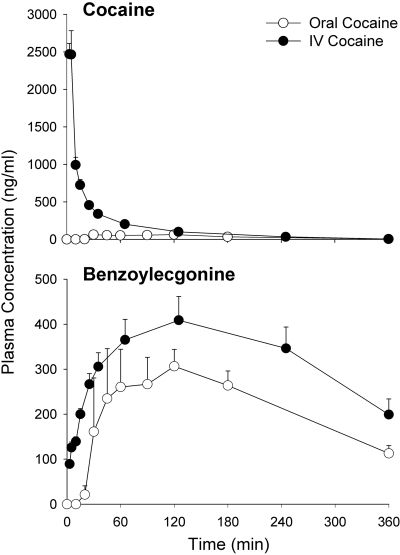

Cocaine and BE pharmacokinetic parameters are summarized in Table 1. Cocaine and corresponding BE concentration-time profiles after administration of oral and intravenous cocaine are shown in Fig. 2. The cocaine AUC0–∞ was approximately 5.5-fold higher after intravenous compared with oral administration. There was no significant difference in the cocaine terminal elimination half-life noted between the two routes of administration. The systemic bioavailability of cocaine was 0.18 ± 0.05. The BE AUC0–∞ was 2-fold higher after intravenous versus oral administration.

TABLE 1.

Cocaine and benzoylecgonine pharmacokinetic parameters

Cocaine and benzoylecgonine AUC values determined after intravenous cocaine administration are normalized to a cocaine dose of 4 mg/kg. The clearance (Cl) values for cocaine given orally represent the oral clearance equivalent to Cl/F. Data are expressed as mean ± S.D.

| Oral Cocaine | Oral Cocaine + EtOH | Intravenous Cocaine | Intravenous Cocaine + EtOH | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUC0–∞ (mg·min/l) | 15.0 ± 4.7*† | 58.6 ± 10.0 | 83.1 ± 15.4† | 110.3 ± 22.5 |

| Cl (l/min) | 5.64 ± 1.84*† | 1.38 ± 0.35 | 0.96 ± 0.19† | 0.74 ± 0.20 |

| Cmax (ng/ml) | 116 ± 98*† | 331 ± 131 | 2677 ± 299 | 2885 ± 702 |

| Tmax(min) | 83.6 ± 46.1 | 99.8 ± 32.5 | ||

| t1/2 (min) | 85.2 ± 6.6 | 84.2 ± 9.1 | 74.9 ± 16.7† | 84.4 ± 8.2 |

| F | 0.18 ± 0.05† | 0.72 ± 0.17 | ||

| CE Cmax (ng/ml) | N.D. | 30.9 ± 7.3 | N.D. | N.D. |

| BE AUC0–∞ (mg·min/l) | 172 ± 46*† | 410 ± 82 | 357 ± 22 | 407 ± 110 |

| BE/cocaine AUC0–∞ | 11.9 ± 3.0*† | 7.1 ± 1.5 | 4.2 ± 0.7 | 3.7 ± 0.6 |

EtOH, ethanol; CE, cocaethylene; N.D., none detected.

p < 0.05 compared with intravenous cocaine.

p < 0.05 compared with corresponding ethanol group given by the same route.

Fig. 2.

Cocaine and benzoylecgonine concentration-time profiles (mean ± S.E.M.) after intravenous and oral administration of cocaine.

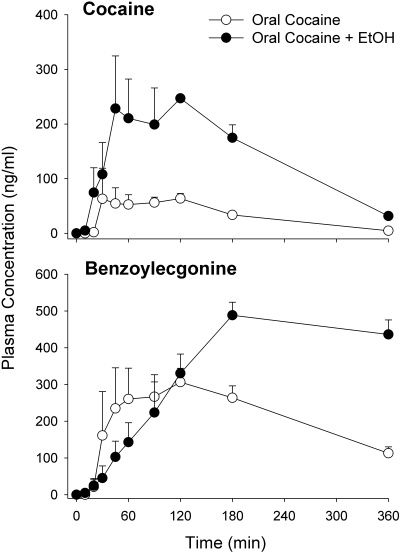

The cocaine and BE plasma concentration-time profiles after oral administration of cocaine with and without ethanol are shown in Fig. 3. Ethanol coadministration produced a 4-fold increase in cocaine AUC0–∞. Oral cocaine systemic bioavailability and Cmax were significantly increased by 4- and 3-fold, respectively, after ethanol administration. Ethanol pretreatment did not affect oral cocaine elimination half-life. The BE AUC0–∞ was approximately 2.5-fold higher with ethanol coadministration than with oral cocaine given alone. Cocaethylene was not detected after the coadministration of ethanol and intravenous cocaine (lower limit of detection was 25 ng/ml), but when ethanol was coadministered with oral cocaine, the mean peak cocaethylene concentration was 30.9 ± 7.3 ng/ml. A significant 33% increase in the intravenous cocaine AUC0–∞was seen with the coadministration of ethanol. Ethanol did not significantly affect the BE AUC0–∞ for intravenous cocaine.

Fig. 3.

Cocaine and benzoylecgonine concentration-time profiles (mean ± S.E.M.) after the oral administration of cocaine with and without ethanol (EtOH).

The metabolite/parent AUC ratios (BE/cocaine) for the four treatment phases are shown in Table 1. For oral compared with intravenous cocaine, the AUC ratio was significantly increased by 2.8-fold. Compared with oral cocaine administered alone, ethanol coadministration reduced the AUC ratio by 40%. Ethanol did not significantly affect the AUC ratios for intravenous cocaine.

Discussion

Cocaine is a carboxylesterase substrate predominantly eliminated by hydrolysis to BE and EME (Fig. 1) by CES1 and CES2 (Isenschmid et al., 1992; Dean et al., 1995; Kamendulis et al., 1996; Cone et al., 1998), and it is one of the few carboxylesterase substrates whose interaction with ethanol has been studied extensively. Studies of the effect of ethanol on cocaine pharmacokinetics have focused on the pharmacodynamic interaction in drug abuse and have reported on administration of cocaine by the intravenous, intraperitoneal, nasal, and smoking routes (Farré et al., 1993; Cami et al., 1998; Laizure et al., 2003). All of these routes of administration bypass the first-pass metabolism of cocaine either completely (intravenous and smoking) or partially (intraperitoneal and intranasal). These studies, performed in both humans and animal models, consistently demonstrate that the coadministration of ethanol inhibits the metabolism of cocaine given by nonoral (intravenous, smoking, intraperitoneal, and intranasal) routes, resulting in an approximate 20 to 50% decrease in the clearance of cocaine (Farré et al., 1993; Parker et al., 1996; Pan and Hedaya 1999). However, cocaine is a high-extraction drug whose elimination after intravenous administration is dependent on liver blood flow, but if given orally the elimination of cocaine will be dependent on the fraction unbound in the plasma and the intrinsic clearance. Thus, the magnitude of the ethanol-mediated effect on carboxylesterase substrate disposition would be expected to be much greater after oral administration. The large first-pass metabolism of cocaine is similar to that of other drugs that are substrates of carboxylesterases, making cocaine an excellent probe drug for evaluating the effect of ethanol on orally administered carboxylesterase substrates. The large increase in the oral bioavailability of cocaine (F increased from 0.18 to 0.72) demonstrates the potent inhibitory effect of ethanol on catalytic hydrolysis and implicates ethanol in a broad class of drug interactions encompassing numerous important therapeutic agents that have carboxylesterase-dependent metabolism.

The hydrolysis of cocaine predominantly to BE and EME has been reported in rats, pigs, monkeys, and humans (Kambam et al., 1992; Saady et al., 1995; Cone et al., 1998; Mets et al., 1999; Evans and Foltin 2004). When cocaine is given by the intravenous or intraperitoneal route, BE is the most abundant metabolite formed followed by EME. This general finding in multiple species of higher BE metabolite levels after intravenous administration of cocaine is evidence of the interspecies consistency of CES1 distribution in the liver and CES2 distribution in the small intestine (Redinbo et al., 2003). Taketani et al. (2007) conducted the most extensive study of interspecies distribution of CES1 and CES2. They reported that CES1 was found mainly in liver tissue with varying amounts of CES2 in different species and that intestinal tissue contained CES2 almost exclusively in all species tested except the dog. Interestingly, they found no carboxylesterase activity (either CES1 or CES2) in the intestine of the dog and no evidence of carboxylesterase proteins from the gel electrophoresis. However, the findings of Taketani et al. (2007) have not been replicated and are not consistent with those from another recent study in the dog, in which prasugrel, a CES2 substrate (Williams et al., 2008), was shown to be rapidly converted to its corresponding thiolactone metabolite in the dog intestine (Hagihara et al., 2009).

Our data and several additional lines of evidence support the potential role of CES2-mediated gut metabolism of carboxylesterase substrate drugs. First, if first-pass metabolism of oral cocaine by CES1 to BE occurs primarily in the liver, then the fraction of the dose converted to BE should be independent of the route of administration. In other words, as shown with other high-extraction drugs such as morphine and propranolol, the dose-normalized AUCs for metabolites formed should be the same for both oral and intravenous routes of administration (Walle et al., 1979; Osborne et al., 1990). In contrast, we found that the dose-adjusted BE AUC was 2-fold higher for intravenous compared with oral cocaine, consistent with intestinal metabolism by an additional pathway. These data, in conjunction with the high levels of CES2 expression in the intestine, suggest that CES2-mediated metabolism in the gut plays an important role in the presystemic metabolism of cocaine (Schwer et al., 1997; Satoh et al., 2002). Second, there are substantial differences in cocaine bioavailability when it is given by the oral than by the intraperitoneal route. In rats, cocaine bioavailability ranges from 0.03 to 0.05 and from 0.55 to 0.65 for oral and intraperitoneal administration, respectively (Ma et al., 1999; Pan and Hedaya, 1999; Sun and Lau, 2001). Because both intraperitoneal and oral doses undergo hepatic first-pass metabolism, the bioavailabilities should be similar if the liver is the only site of metabolism. Therefore, the marked difference in bioavailability between these two routes of administration further suggests that cocaine undergoes intestinal metabolism.

These data indicate that generalizing the effect of ethanol on cocaine metabolism in the dog to humans is a reasonable supposition. In addition, human studies of the interaction between intravenously administered cocaine and ethanol are plentiful and indicate that the clearance of cocaine is inhibited to a similar degree in both dogs and humans after coadministration with ethanol (Farré et al., 1993; Roberts et al., 1993; Harris et al., 2003; Laizure et al., 2003). Additional evidence that ethanol inhibits carboxylesterase hydrolysis in humans is reported for methylphenidate. Methylphenidate undergoes high first-pass metabolism by CES1 to the inactive metabolite, ritalinic acid. The coadministration of ethanol caused a 27% increase in the AUC and a 41% increase in the Cmax of orally administered methylphenidate in human volunteers (Patrick et al., 2007). These results are further evidence that the inhibition of carboxylesterases by ethanol demonstrated in our study is applicable to humans and to other drugs that are carboxylesterase substrates. It is interesting to note that the change in bioavailability of methylphenidate is much less than the change in the bioavailability of cocaine that we observed in the dog. Despite the well conserved nature of carboxylesterase activity in mammals, there are significant interspecies differences in both the distribution and activity of specific carboxylesterase enzymes (Satoh and Hosokawa 1995; Song et al., 1999; Takahashi et al., 2009). Another factor could be that although methylphenidate is a CES1 substrate, cocaine is both a CES1 and CES2 substrate, and our data suggest that ethanol is an inhibitor of both carboxylesterases. If ethanol is a potent CES2 inhibitor, this could explain the greater effect of ethanol coadministration on cocaine versus methylphenidate bioavailability.

As noted by Patrick et al. (2007) in their human study of the interaction between ethanol and methylphenidate, the inhibition of carboxylesterase hydrolysis by ethanol could be due to the direct inhibition of carboxylesterase activity by ethanol or competitive inhibition with the ethylated metabolite formed by transesterification. This is an important consideration because it has been previously demonstrated that cocaethylene inhibits the elimination of cocaine (Parker et al., 1996). However, the concentrations required to achieve a 25% reduction in cocaine clearance were more than 100-fold higher (3796 ± 857 versus 30.9 ± 7.3 ng/ml) than the cocaethylene Cmax that occurred in this study (Parker et al., 1996, 1998). This finding strongly suggests that the cocaethylene concentrations achieved in the present study are nonpharmacological and that inhibition of the hydrolysis of cocaine is due to the direct inhibition of carboxylesterase activity by ethanol.

Our findings identify a new class of drug-drug interactions, ethanol-mediated inhibition of carboxylesterase hydrolysis, which may significantly affect the disposition of a number of widely prescribed drugs that are esters. Most of the ester drugs on the market are inactive prodrugs that are designed to be rapidly metabolized by carboxylesterases and, like cocaine, are high-extraction drugs with a large first-pass metabolism. Therefore, ethanol, by inhibiting carboxylesterases, would reduce the formation rate of the active moiety. In this case, ethanol would be expected to markedly reduce the systemic exposure of the active compound and attenuate the therapeutic effects. An important example would be oseltamivir phosphate, which is an inactive ester prodrug that was specifically developed to overcome the poor oral bioavailability of oseltamivir carboxylate (the active neuramidase inhibitor). Oseltamivir phosphate is rapidly absorbed and converted to oseltamivir carboxylate by CES1 (He et al., 1999). The exception to this rapid conversion is in rare individuals who are poor converters (Zhu and Markowitz 2009). Rare genetic variants have been documented that result in low carboxylesterase activity, and this has led to concerns that individuals with variant alleles will not achieve therapeutic effects because of their inability to hydrolyze the prodrug to its active form. It is quite possible given the potent inhibitory effect of ethanol on hydrolysis that it could result in poor conversion rates similar to what is seen with variant alleles. Such a drug interaction would be expected to decrease the efficacy of oseltamivir against influenza viruses including the H1N1 strain, and it would be a far more frequent occurrence than the incidence of variant alleles. With more than 100 million people in the United States using ethanol (SAMHSA, 2004) and the common use of ethanol as a vehicle in cold medications, the potential health implications of the interaction between ethanol and oseltamivir are significant on both an individual and societal basis.

Clopidogrel and prasugrel, which are members of the widely prescribed thienopyridine antiplatelet drug class, may also interact with ethanol. Clopidogrel is metabolized by the cytochrome P450 system to the intermediate inactive thiolactone metabolite and then to the active metabolite. Both clopidogrel and the intermediate thiolactone are subject to hydrolysis by CES1, a competing pathway, resulting in inactive metabolites. Ethanol, by inhibiting hydrolysis by CES1, would be expected to increase the formation of the active metabolite by the cytochrome P450 system, increasing the antiplatelet effect of clopidogrel. In contrast, prasugrel is converted to its thiolactone metabolite by CES2 in the intestines, and the thiolactone metabolite is converted to the active metabolite by the cytochrome P450 system. Ethanol would decrease the formation of the thiolactone metabolite, increasing the bioavailability of prasugrel. The absorbed prasugrel would no longer have access to CES2, which is primarily localized in the small intestine, so lower levels of the thiolactone metabolite would be available for conversion to the active metabolite. Ethanol would be expected to decrease the antiplatelet effect when coadministered with prasugrel.

The clinical effect of the interaction of ethanol with specific drugs can be postulated based on a knowledge of the drug's metabolic pathway and pharmacodynamics, but ultimately human studies are required before this information can be used to guide therapy in patients. The list of drugs in Table 2 identifies a number of widely prescribed therapeutic agents that are known substrates of carboxylesterases (Pindel et al., 1997; Slatter et al., 1997; Zhang et al., 1999; Quinney et al., 2005; Satoh and Hosokawa 2006; Tang et al., 2006; Farid et al., 2007; Patrick et al., 2007; Williams et al., 2008; Yang et al., 2009) and gives a perspective on the potential broad clinical implications of this interaction. The potential of ethanol to interact with commonly prescribed drugs by inhibition of hydrolysis has not been considered; however, the potent ethanol-mediated inhibition of carboxylesterase hydrolysis demonstrated in the present study identifies a need for clinical studies with specific drugs to establish a better understanding of the carboxylesterase-ethanol interaction and the therapeutic implications.

TABLE 2.

Common drugs that undergo hydrolysis by carboxylesterases

| CES1 | CES2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrolysis to active metabolite | Oseltamivir | Prasugrela |

| Benazepril | Irinotecan | |

| Quinapril | Lovastatin | |

| Imidapril | Simvastatin | |

| Hydrolysis to inactive metabolite | Clopidogrel | Cocaine |

| Methylphenidate | Aspirin | |

| Meperidine |

Prasugrel is hydrolyzed to an inactive metabolite that is the precursor of the active moiety.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [Grant R15HL54311].

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at http://dmd.aspetjournals.org.

doi:10.1124/dmd.109.030056

- CES1

- carboxylesterase 1

- CES2

- carboxylesterase 2

- BE

- benzoylecgonine

- EME

- ecgonine methyl ester

- AUC

- area under the plasma concentration-time curve.

References

- Brzezinski MR, Abraham TL, Stone CL, Dean RA, Bosron WF. (1994) Purification and characterization of a human liver cocaine carboxylesterase that catalyzes the production of benzoylecgonine and the formation of cocaethylene from alcohol and cocaine. Biochem Pharmacol 48: 1747–1755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cami J, Farré M, González ML, Segura J, de la Torre R. (1998) Cocaine metabolism in humans after use of alcohol. Clinical and research implications. Recent Dev Alcohol 14: 437–455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cone EJ, Tsadik A, Oyler J, Darwin WD. (1998) Cocaine metabolism and urinary excretion after different routes of administration. Ther Drug Monit 20: 556–560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean RA, Christian CD, Sample RH, Bosron WF. (1991) Human liver cocaine esterases: ethanol-mediated formation of ethylcocaine. FASEB J 5: 2735–2739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean RA, Harper ET, Dumaual N, Stoeckel DA, Bosron WF. (1992) Effects of ethanol on cocaine metabolism: formation of cocaethylene and norcocaethylene. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 117: 1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean RA, Zhang J, Brzezinski MR, Bosron WF. (1995) Tissue distribution of cocaine methyl esterase and ethyl transferase activities: correlation with carboxylesterase protein. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 275: 965–971 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans SM, Foltin RW. (2004) Pharmacokinetics of intravenous cocaine across the menstrual cycle in rhesus monkeys. Neuropsychopharmacology 29: 1889–1900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farid NA, Small DS, Payne CD, Jakubowski JA, Brandt JT, Li YG, Ernest CS, Salazar DE, Konkoy CS, Winters KJ. (2008) Effect of atorvastatin on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of prasugrel and clopidogrel in healthy subjects. Pharmacotherapy 28: 1483–1494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farid NA, Smith RL, Gillespie TA, Rash TJ, Blair PE, Kurihara A, Goldberg MJ. (2007) The disposition of prasugrel, a novel thienopyridine, in humans. Drug Metab Dispos 35: 1096–1104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farré M, de la Torre R, Llorente M, Lamas X, Ugena B, Segura J, Camí J. (1993) Alcohol and cocaine interactions in humans. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 266: 1364–1373 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagihara K, Kazui M, Ikenaga H, Nanba T, Fusegawa K, Takahashi M, Kurihara A, Okazaki O, Farid NA, Ikeda T. (2009) Comparison of formation of thiolactones and active metabolites of prasugrel and clopidogrel in rats and dogs. Xenobiotica 39: 218–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris DS, Everhart ET, Mendelson J, Jones RT. (2003) The pharmacology of cocaethylene in humans following cocaine and ethanol administration. Drug Alcohol Depend 72: 169–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He G, Massarella J, Ward P. (1999) Clinical pharmacokinetics of the prodrug oseltamivir and its active metabolite Ro 64-0802. Clin Pharmacokinet 37: 471–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henning RJ, Wilson LD, Glauser JM. (1994) Cocaine plus ethanol is more cardiotoxic than cocaine or ethanol alone. Crit Care Med 22: 1896–1906 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources (1996)Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals,7th ed.Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources, Commission on Life Sciences, National Research Council,Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Isenschmid DS, Fischman MW, Foltin RW, Caplan YH. (1992) Concentration of cocaine and metabolites in plasma of humans following intravenous administration and smoking of cocaine. J Anal Toxicol 16: 311–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kambam J, Mets B, Hickman RM, Janicki P, James MF, Fuller B, Kirsch RE. (1992) The effects of inhibition of plasma cholinesterase and hepatic microsomal enzyme activity on cocaine, benzoylecgonine, ecgonine methyl ester, and norcocaine blood levels in pigs. J Lab Clin Med 120: 323–328 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamendulis LM, Brzezinski MR, Pindel EV, Bosron WF, Dean RA. (1996) Metabolism of cocaine and heroin is catalyzed by the same human liver carboxylesterases. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 279: 713–717 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laizure SC, Mandrell T, Gades NM, Parker RB. (2003) Cocaethylene metabolism and interaction with cocaine and ethanol: role of carboxylesterases. Drug Metab Dispos 31: 16–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma F, Falk JL, Lau CE. (1999) Cocaine pharmacodynamics after intravenous and oral administration in rats: relation to pharmacokinetics. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 144: 323–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCance-Katz EF, Price LH, McDougle CJ, Kosten TR, Black JE, Jatlow PI. (1993) Concurrent cocaine-ethanol ingestion in humans: pharmacology, physiology, behavior, and the role of cocaethylene. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 111: 39–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mets B, Diaz J, Soo E, Jamdar S. (1999) Cocaine, norcocaine, ecgonine methylester and benzoylecgonine pharmacokinetics in the rat. Life Sci 65: 1317–1328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne R, Joel S, Trew D, Slevin M. (1990) Morphine and metabolite behavior after different routes of morphine administration: demonstration of the importance of the active metabolite morphine-6-glucuronide. Clin Pharmacol Ther 47: 12–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan WJ, Hedaya MA. (1999) Cocaine and alcohol interactions in the rat: effect of cocaine and alcohol pretreatments on cocaine pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. J Pharm Sci 88: 1266–1274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker RB, Laizure SC, Williams CL, Mandrell TD, Lima JJ. (1998) Evaluation of dose-dependent pharmacokinetics of cocaethylene and cocaine in conscious dogs. Life Sci 62: 333–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker RB, Williams CL, Laizure SC, Mandrell TD, LaBranche GS, Lima JJ. (1996) Effects of ethanol and cocaethylene on cocaine pharmacokinetics in conscious dogs. Drug Metab Dispos 24: 850–853 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick KS, Straughn AB, Minhinnett RR, Yeatts SD, Herrin AE, DeVane CL, Malcolm R, Janis GC, Markowitz JS. (2007) Influence of ethanol and gender on methylphenidate pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Clin Pharmacol Ther 81: 346–353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pindel EV, Kedishvili NY, Abraham TL, Brzezinski MR, Zhang J, Dean RA, Bosron WF. (1997) Purification and cloning of a broad substrate specificity human liver carboxylesterase that catalyzes the hydrolysis of cocaine and heroin. J Biol Chem 272: 14769–14775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinney SK, Sanghani SP, Davis WI, Hurley TD, Sun Z, Murry DJ, Bosron WF. (2005) Hydrolysis of capecitabine to 5′-deoxy-5-fluorocytidine by human carboxylesterases and inhibition by loperamide. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 313: 1011–1016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redinbo MR, Bencharit S, Potter PM. (2003) Human carboxylesterase 1: from drug metabolism to drug discovery. Biochem Soc Trans 31: 620–624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts SM, Harbison RD, James RC. (1993) Inhibition by ethanol of the metabolism of cocaine to benzoylecgonine and ecgonine methyl ester in mouse and human liver. Drug Metab Dispos 21: 537–541 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saady JJ, Bowman ER, Aceto MD. (1995) Cocaine, ecgonine methyl ester, and benzoylecgonine plasma profiles in rhesus monkeys. J Anal Toxicol 19: 571–575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAMHSA (2004)Results from the 2004 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings. Substance Abuse and Health Services Administration, Department of Health and Human Services, Rockville, MD [Google Scholar]

- Satoh T, Hosokawa M. (1995) Molecular aspects of carboxylesterase isoforms in comparison with other esterases. Toxicol Lett 82–83: 439–445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satoh T, Hosokawa M. (1998) The mammalian carboxylesterases: from molecules to functions. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 38: 257–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satoh T, Hosokawa M. (2006) Structure, function and regulation of carboxylesterases. Chem Biol Interact 162: 195–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satoh T, Taylor P, Bosron WF, Sanghani SP, Hosokawa M, La Du BN. (2002) Current progress on esterases: from molecular structure to function. Drug Metab Dispos 30: 488–493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwer H, Langmann T, Daig R, Becker A, Aslanidis C, Schmitz G. (1997) Molecular cloning and characterization of a novel putative carboxylesterase, present in human intestine and liver. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 233: 117–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slatter JG, Su P, Sams JP, Schaaf LJ, Wienkers LC. (1997) Bioactivation of the anticancer agent CPT-11 to SN-38 by human hepatic microsomal carboxylesterases and the in vitro assessment of potential drug interactions. Drug Metab Dispos 25: 1157–1164 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song N, Parker RB, Laizure SC. (1999) Cocaethylene formation in rat, dog, and human hepatic microsomes. Life Sci 64: 2101–2108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L, Lau CE. (2001) Simultaneous pharmacokinetic modeling of cocaine and its metabolites, norcocaine and benzoylecgonine, after intravenous and oral administration in rats. Drug Metab Dispos 29: 1183–1189 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi S, Katoh M, Saitoh T, Nakajima M, Yokoi T. (2009) Different inhibitory effects in rat and human carboxylesterases. Drug Metab Dispos 37: 956–961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taketani M, Shii M, Ohura K, Ninomiya S, Imai T. (2007) Carboxylesterase in the liver and small intestine of experimental animals and human. Life Sci 81: 924–932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang M, Mukundan M, Yang J, Charpentier N, LeCluyse EL, Black C, Yang D, Shi D, Yan B. (2006) Antiplatelet agents aspirin and clopidogrel are hydrolyzed by distinct carboxylesterases, and clopidogrel is transesterificated in the presence of ethyl alcohol. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 319: 1467–1476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walle T, Conradi EC, Walle UK, Fagan TC, Gaffney TE. (1979) Naphthoxylactic acid after single and long-term doses of propranolol. Clin Pharmacol Ther 26: 548–554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams CL, Laizure SC, Parker RB, Lima JJ. (1996) Quantitation of cocaine and cocaethylene in canine serum by high-performance liquid chromatography. J Chromatogr B Biomed Appl 681: 271–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams ET, Jones KO, Ponsler GD, Lowery SM, Perkins EJ, Wrighton SA, Ruterbories KJ, Kazui M, Farid NA. (2008) The biotransformation of prasugrel, a new thienopyridine prodrug, by the human carboxylesterases 1 and 2. Drug Metab Dispos 36: 1227–1232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang D, Pearce RE, Wang X, Gaedigk R, Wan YJ, Yan B. (2009) Human carboxylesterases HCE1 and HCE2: ontogenic expression, inter-individual variability and differential hydrolysis of oseltamivir, aspirin, deltamethrin and permethrin. Biochem Pharmacol 77: 238–247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Burnell JC, Dumaual N, Bosron WF. (1999) Binding and hydrolysis of meperidine by human liver carboxylesterase hCE-1. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 290: 314–318 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu HJ, Markowitz JS. (2009) Activation of the antiviral prodrug oseltamivir is impaired by two newly identified carboxylesterase 1 variants. Drug Metab Dispos 37: 264–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]