Abstract

Blood-stage malaria parasites ablate memory B cells generated by vaccination in mice, resulting in diminishing natural boosting of vaccine-induced antibody responses to infection. Here we show the development of a new vaccine comprising a baculovirus-based Plasmodium yoelii 19-kDa carboxyl terminus of merozoite surface protein 1 (PyMSP119) capable of circumventing the tactics of parasites in a murine model. The baculovirus-based vaccine displayed PyMSP119 on the surface of the virus envelope in its native three-dimensional structure. Needle-free intranasal immunization of mice with the baculovirus-based vaccine induced strong systemic humoral immune responses with high titers of PyMSP119-specific antibodies. Most importantly, this vaccine conferred complete protection by natural boosting of vaccine-induced PyMSP119-specific antibody responses shortly after challenge. The protective mechanism is a mixed Th1/Th2-type immunity, which is associated with the Toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9)-dependent pathway. The present study offers a novel strategy for the development of malaria blood-stage vaccines capable of naturally boosting vaccine-induced antibody responses to infection.

Malaria, which is transmitted by anopheline mosquitoes, is an enormous public health problem worldwide and every year kills 1 to 2 million people, mostly children residing in Africa. Clearly, an effective vaccine for the control of malaria is urgently needed.

The 42-kDa carboxyl terminus of merozoite surface protein 1 (MSP142) is a leading malaria vaccine candidate. In a murine model, vaccination with the 19-kDa carboxyl terminus of Plasmodium yoelii MSP1 (PyMSP119) confers protection against challenge, and the protective immunity correlates with the high titer of PyMSP119-specific antibodies (6, 15). Despite its promising potential, none of the MSP1-based Plasmodium falciparum vaccine candidates have shown satisfactory outcomes in human clinical trials. With current antigen-adjuvant formulations, it has been difficult to induce robust antibody responses in humans (18). Besides the poor immunogenicity, polymorphisms in the P. falciparum msp1 gene are thought to represent another big obstacle for the development of vaccines based on this molecule (24, 29).

Are poor immunogenicity and gene polymorphism really the main reasons why the MSP1-based vaccine candidates in human phase II trials are much less effective than those in animal models? In a murine model, immunization with recombinant PyMSP119 vaccines in Freund's adjuvant induced high titers of PyMSP119-specific antibodies, leading to protection against lethal challenge. Although the PyMSP119-specific antibodies at the time of infection are consumed to impair P. yoelii growth, no natural boosting of vaccine-induced PyMSP119-specific antibody responses is elicited during infection (31). Recent studies demonstrated that the parasite induces apoptotic deletion of vaccine-specific memory B cells, long-lived plasma cells, and CD4+ T cells, resulting in failure of the naturally boosting antibody response to malaria parasites during infection (13, 32, 33). This is supported by sero-epidemiological studies showing that a significant proportion of Africans do not possess IgG antibodies to P. falciparum MSP1 despite repeat exposure to malaria (9-11). Thus, it is likely that malaria parasites manipulate the host's apoptotic pathway to subvert the generation and/or maintenance of immunological memory (21). To date, however, little evidence has been documented on a host's immune response to infection, specifically regarding the natural boosting associated with vaccine-induced immune responses (26). Most malaria vaccine studies with animal models and in human clinical trials have focused mainly on the evaluation of immunization-induced immune responses present before challenge. We hypothesize that the limited success of blood-stage vaccines in human clinical trials is mainly due to apoptosis induction of vaccine-induced memory B cells by the parasite. If so, it is essential to develop a new vaccine vector capable not only of inducing strong protective immune responses but also of circumventing the parasite-induced apoptosis of vaccine-specific immune cells.

The baculovirus Autographa californica nucleopolyhedrosis virus (AcNPV) is an enveloped, double-stranded DNA virus that naturally infects insects. AcNPV has long been used as a biopesticide and as a tool for efficient production of complex animal, human, and viral proteins that require folding, subunit assembly, and extensive posttranslational modification in insect cells (22, 23). In recent years, AcNPV has been engineered for expression of complex eukaryotic proteins (e.g., vaccine candidate antigens) on the surface of the viral envelope (12, 17, 25, 34, 35) and has emerged as a new vaccine vector with several attractive attributes, including (i) low cytotoxicity, (ii) an inability to replicate in mammalian cells, and (iii) an absence of preexisting antibodies. AcNPV also possesses strong adjuvant properties which can activate dendritic cell (DC)-mediated innate immunity through MyD88/Toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9)-dependent and -independent pathways (1), and intranasal (i.n.) immunization with AcNPV protects mice from a lethal challenge of influenza virus through innate immune responses (2). Therefore, nasal mucosal tissues, which are abundant in DCs and macrophages, may be attractive sites for immunization with AcNPV-based vaccines to induce TLR9-mediated immune responses.

In the present study, we describe i.n. immunization with an AcNPV-based PyMSP119 vaccine (AcNPV-PyMSP119surf) as a model of a blood-stage vaccine and evaluate the vaccine efficacy in a murine model. Needle-free nasal drop immunization with this vaccine induced not only strong systemic humoral immune responses with high titers of PyMSP119-specific antibodies but also natural boosting of PyMSP119-specific antibody responses shortly after challenge, conferring complete protection. These results suggest that the needle-free nasal drop malaria vaccine based on the baculoviral vector could open a new avenue to developing a novel blood-stage malaria vaccine delivery platform.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice and parasites.

Female BALB/c mice, 7 to 8 weeks of age at the start of the experiment, were purchased from Nippon Clea (Saitama, Japan). TLR9-deficient mice on a BALB/c background were kindly provided by S. Akira (University of Osaka, Suita, Japan). P. yoelii 17XL, a lethal murine malaria parasite, was kindly provided by T. Tsuboi (Ehime University, Matsuyama, Japan) and used for challenge infections.

Recombinant baculovirus.

The DNA sequence corresponding to amino acids Pro1659 to Gly1757 of P. yoelii 17XL MSP119 was amplified using the primers pPyMSP119-F1 (5′-CTGCAGGACTACAAGGACGACGATGACAAGGAATTCGGTGTAGACCCTAAACATGTATGTGTTGATACAAGAGAT-3′) and pPyMSP119-R1 (5′-CCCGGGCTCCCATAAAGCTGGAAGAACTACAGAATACACCT-3′). The resulting PCR product was ligated into the PstI/SmaI sites of pBACsurf-1 (Novagen, Madison, WI) to construct a baculovirus transfer vector, pBACsurf-PyMSP119. A recombinant baculovirus, AcNPV-PyMSP119surf, was generated according to the manufacturer's (Novagen) protocol. The purified baculovirus particles were free of endotoxin (<0.01 endotoxin unit/109 PFU), as determined by use of an Endospecy endotoxin measurement kit (Seikagaku Co., Tokyo, Japan).

Recombinant proteins.

A recombinant PyMSP119 protein of P. yoelii 17XL, created as a fusion protein with glutathione S-transferase (GST-PyMSP119), was expressed in Escherichia coli, purified using a GST affinity column (GE Healthcare) as described previously (5), and used as an immunogen for vaccination of mice and as an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) antigen. A recombinant PyMSP119 protein of P. yoelii 17XL (yMSP119), produced as a His6-tagged protein in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, was obtained from MR4 (Manassas, VA) and used as an ELISA antigen. We confirmed that GST-PyMSP119 and yMSP119 were equally recognized by P. yoelii-hyperimmune sera, which were obtained from BALB/c mice that had recovered from repeated P. yoelii 17XL infection by treatment with chloroquine as described previously (8). We also confirmed that the GST-PyMSP119 and yMSP119 proteins were antigenically equivalent in the ELISA by using sera from AcNPV-PyMSP119surf-immunized mice.

Western blotting, IFA, and immuno-electron microscopy.

Western blotting, indirect immunofluorescence assay (IFA), and immuno-electron microscopy were carried out as described previously (34). Full details of these methods are provided in the supplemental material.

Immunization and challenge infections.

Mice were immunized three times at 3-week intervals with 5 × 107 PFU of baculovirus virions by either the intramuscular (i.m.) or intranasal (i.n.) route. For i.n. immunization, a total of 50 μl, which was divided into three doses at 5-min intervals, was inoculated by nasal drop with a Pipetman pipette. As a comparative control, mice were immunized intraperitoneally (i.p.) with 50 μg of GST-PyMSP119 in 2 mg of aluminum hydroxide (Imject alum; Pierce) three times at 3-week intervals. For oral immunization, mice were deprived of food and water for 4 h and then orally immunized four times at 2-week intervals with 0.2 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing AcNPV-PyMSP119surf (5 × 107 PFU), GST-PyMSP119 (50 μg), or GST-PyMSP119 (50 μg) plus wild-type AcNPV (AcNPV-WT) (5 × 107 PFU) by intubation with an animal-feeding needle (Natsume, Tokyo, Japan). For each route of immunization, sera were collected and mice were challenged with 1 × 103 live P. yoelii 17XL-parasitized red blood cells (pRBC) by intravenous (i.v.) injection 2 weeks after the final immunization. To examine the vaccine efficacy of AcNPV-PyMSP119surf, the baculovirus-produced PyMSP119 protein may be more suitable as a reference immunogen than E. coli-produced GST-PyMSP119. However, our conventional purification methods cannot remove small traces of contamination of baculovirus virions and genomic DNA, which have strong adjuvant properties to induce innate immunity. Therefore, the present study used E. coli-produced GST-PyMSP119 as a standard recombinant PyMSP119 vaccine formulated with alum. The course of parasitemia was monitored by microscopic examination of Giemsa-stained thin blood smears obtained from tail bleeds. All care and handling of the animals were in accordance with the guidelines for animal care and use prepared by Jichi Medical University.

ELISA for antibody titers and isotypes.

Sera obtained from immunized mice were collected by tail bleeds 2 weeks after the final immunization, prior to challenge. For some mice, sera were also collected periodically after challenge. For PyMSP119-specific antibodies of mice immunized with AcNPV-based vaccines, precoated ELISA plates with 100 ng/well GST-PyMSP119 were incubated with serial dilutions of sera. For PyMSP119-specific antibodies of mice immunized with GST-PyMSP119, precoated ELISA plates with 100 ng/well yPyMSP119 were incubated with serial dilutions of sera to avoid cross-reaction with GST. We confirmed that sera obtained from mice immunized with AcNPV-PyMSP119surf reacted equally with GST-PyMSP119 and yPyMSP119. For blood-stage parasite-specific antibodies, P. yoelii 17XL antigen was prepared from blood of P. yoelii 17XL-infected mice as described previously (3). Specific IgGs were detected using horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L) (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). For isotype determination, HRP-conjugated rabbit anti-mouse IgM, IgGγ (Southern Biotechnology Associates Inc., Birmingham, AL), IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b, and IgG3 (Zymed Laboratories, San Francisco, CA) antibodies were used. The plates were developed with peroxidase substrate solution [H2O2 and 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulfonic acid)]. The optical density (OD) at 414 nm of each well was measured using a plate reader. End-point titers were expressed as the reciprocal of the highest sample dilution for which the OD was equal to or greater than the mean OD for nonimmune control sera.

Cytokine detection.

Sera were collected at various times after challenge and stored at −80°C until analysis. The presence of cytokines was analyzed using the BioPlex system (Bio-Rad) as described by de Jager et al. (7). The following cytokines were analyzed: interleukin-2 (IL-2), IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, IL-12p70, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), gamma interferon (IFN-γ), and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α).

Statistical analyses.

Statistical analysis was performed with Graphpad Prism software (Graphpad Software Inc.). Fisher's exact probability test was used to compare the numbers of surviving animals in different groups, and the Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare peak levels of parasitemia between two groups. Wilcoxon and Mann-Whitney U tests were used to compare antibody levels between groups for paired and unpaired data, respectively. Spearman's rank correlation test was used to assess associations between antibody levels and maximal parasitemia. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant for these analyses.

RESULTS

Construction of baculovirus-based PyMSP119 vaccine.

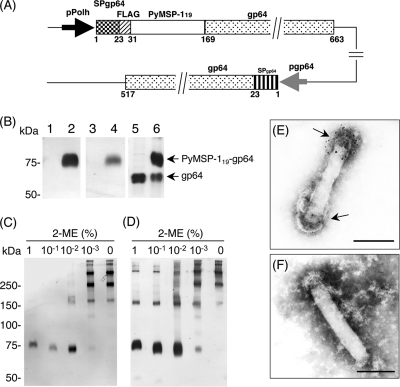

AcNPV-PyMSP119surf harbored a gene cassette that consisted of the gp64 signal sequence and the Pymsp119 gene fused to the N terminus of the coding region for the AcNPV major envelope protein gp64 under the control of the polyhedrin promoter (Fig. 1A). Western blot analysis showed that both anti-FLAG monoclonal antibody (MAb) and P. yoelii-hyperimmune serum recognized the PyMSP119-gp64 fusion protein, at a molecular mass of 75 kDa (Fig. 1B, lanes 2 and 4, respectively). AcNPV-PyMSP119surf was treated with 10-fold serial dilutions of 2-mercaptoethanol (2-ME). Reduction of the concentration of 2-ME increased the reactivity of the 75-kDa band for P. yoelii-hyperimmune serum (Fig. 1C). In contrast, anti-FLAG MAb, which recognizes a linear epitope, retained the same reactivity of the 75-kDa band irrespective of the 2-ME concentration (Fig. 1D). Immuno-electron microscopy showed that PyMSP119 was displayed on the viral envelope of AcNPV-PyMSP119surf (Fig. 1E). These results indicate that the PyMSP119-gp64 fusion protein forms oligomers on the virus envelope and retains the three-dimensional structure of the native PyMSP119 protein with correctly formed disulfide bonds.

FIG. 1.

Construction and analysis of recombinant AcNPV expressing PyMSP119. (A) Schematic diagram of AcNPV-PyMSP119surf genome. PyMSP119 was expressed as a PyMSP119-gp64 fusion protein under the control of the polyhedron promoter. Numbers indicate the amino acid positions of the PyMSP119-gp64 fusion protein and the endogenous gp64 protein. pPolh, polyhedrin promoter; SP, gp64 signal sequence; FLAG, FLAG epitope tag; pgp64, gp64 promoter. (B) Western blot analysis of AcNPV-PyMSP119surf. AcNPV-WT (lanes 1, 3, and 5) and AcNPV-PyMSP119surf (lanes 2, 4, and 6) were treated with loading buffer containing 1% 2-ME and examined using anti-FLAG MAb (lanes 1and 2), P. yoelii-hyperimmune serum (lanes 3 and 4), and anti-gp64 MAb (lanes 5 and 6). Arrows indicate the positions of PyMSP119-gp64 fusion protein and endogenous gp64. (C and D) Structural analysis of PyMSP119-gp64 fusion protein. AcNPV-PyMSP119surf was treated with loading buffer containing various concentrations of 2-ME. The reactivity of the PyMSP119-gp64 fusion protein was examined using either P. yoelii-hyperimmune serum (C) or anti-FLAG MAb (D). The concentrations of 2-ME are shown at the top. (E and F) Electron micrographs of AcNPV-PyMSP119surf displaying PyMSP119 on the viral envelope. AcNPV-PyMSP119surf was treated with either mouse anti-GST-PyMSP119 antiserum (E) or normal mouse serum (F) followed by labeling with anti-mouse-gold conjugate. The surfaces of the virions were strongly labeled with gold particles (arrows). Bars, 100 nm.

i.n. immunization with AcNPV-PyMSP119surf induces high levels of PyMSP119-specific antibody titer.

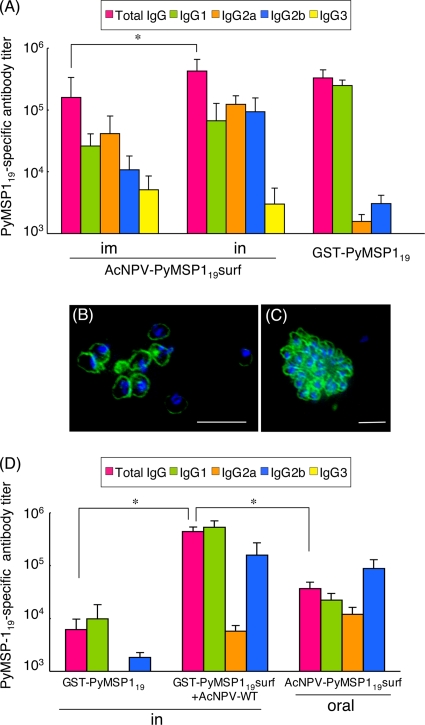

i.n. immunization with AcNPV-PyMSP119surf induced significantly higher PyMSP119-specific antibody titer levels than did i.m. immunization (2.7-fold; P < 0.01) (Fig. 2A). Immune sera obtained after immunization through the i.m. and i.n. routes contained predominantly IgG1 and IgG2a (IgG1-to-IgG2a ratio ≅ 0.63 and 0.54, respectively), indicating a mixed Th1/Th2-type immune response. The mucosal immunization-inducible IgG2b was significantly increased in the group receiving i.n. immunization. Immunization with GST-PyMSP119 in alum induced a predominantly Th2-type immune response characterized by a high IgG1/IgG2a ratio (≅159). The total PyMSP119-specific antibody levels were not different between the GST-PyMSP119 and i.n. AcNPV-PyMSP119surf groups. The IgG3 antibody was undetectable in the GST-PyMSP119 group (<1:100). Thus, each vaccination regimen induced different IgG class switching. These immune sera strongly reacted with native PyMSP119 on the parasites, with circumferential staining on the surfaces of free merozoites (Fig. 2B) after schizont rupture in addition to the detection of PyMSP119 in mature schizonts (Fig. 2C).

FIG. 2.

PyMSP119-specific antibody responses. Sera were collected from individual mice (10 mice/group) 3 weeks after the last immunization. (A) The individual sera were tested for total IgG, IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b, and IgG3 specific for PyMSP119 by ELISA. The data represent one of two experiments, which had similar results. Data are presented as means ± standard deviations (SD) for the groups. Significant differences in total IgG titers between different groups were evaluated using two-tailed Fisher's exact probability test. *, P < 0.01. (B and C) Confocal fluorescence micrographs of sera obtained from mice immunized with AcNPV-PyMSP119surf. Free merozoites (B) and mature schizonts (C) were clearly stained (green) by serum (1:500 dilution) obtained from one mouse immunized i.n. with AcNPV-PyMSP119surf. Cell nuclei were visualized by DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) staining (blue). Similar results were observed for all sera obtained from mice immunized i.m. and i.n. with AcNPV-PyMSP119surf. Bar, 10 μm. (D) PyMSP119-specific antibody responses induced by mucosal immunization regimens. Groups of mice (n = 10) were immunized either i.n. with GST-PyMSP119 plus AcNPV-WT, i.n. with GST-PyMSP119 alone, or orally with AcNPV-PyMSP119surf. Sera were collected from individual mice 3 weeks after the last immunization and tested for PyMSP119-specific antibodies and IgG isotypes by ELISA. Ig63 was undetectable in all groups. Data are presented as means ± SD for the groups. *, P < 0.01.

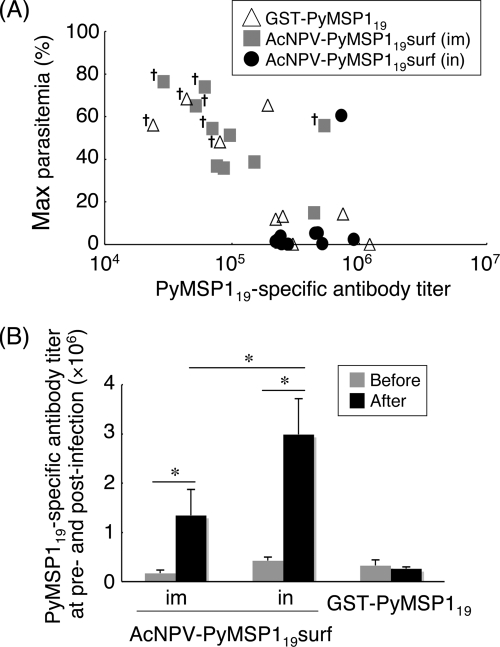

Protection of mice immunized with AcNPV-PyMSP119surf against challenge infection.

The groups of immunized mice were challenged i.v. with lethal P. yoelii 17XL, and the course of infection was monitored (Table 1). All but one of the nonimmunized control mice died with high parasitemia (76%) by day 8 postchallenge. Mice immunized either i.m. or i.n. with AcNPV-WT suffered severe courses of infection with high maximum parasitemia levels (>70% parasitemia) and 100% mortality, indicating that AcNPV alone had no protective effect. In the i.m. AcNPV-PyMSP119surf group, 7 of 15 mice survived after challenge, with high maximum parasitemia (mean ± standard error of the mean [SEM], 51.1% ± 5.1%). All mice immunized with i.n. AcNPV-PyMSP119surf survived after challenge. Compared with the i.m. AcNPV-PyMSP119surf group, the i.n. AcNPV-PyMSP119surf group experienced significantly lower maximum parasitemia levels (7.56% ± 3.95%; P < 0.01) and earlier parasite clearance (14.7 ± 1.4 days; P < 0.05). In the GST-PyMSP119 group, 7 of 15 mice survived after challenge, with moderate maximum parasitemia (37.8% ± 7.2%). PyMSP119-specific antibody titers were inversely related to maximal parasitemia, and reduction of parasitemia and protection from death depended upon a high titer of PyMSP119-specific antibodies at challenge (Fig. 3A). Antibody titers over 1:80,000 conferred 100% (22/22 mice) survival, while antibody titers under 1:80,000 resulted in high parasitemia and 12.5% (1/8 mice) survival. Thus, i.n. immunization with AcNPV-PyMSP119surf induced a solid level of protection against a lethal challenge infection. Interestingly, the protection efficacy was only 40% (2/5 mice) in the i.n GST-PyMSP119-plus-AcNPV-WT immunization group (Table 1), despite high titers of PyMSP119-specific antibodies (≅4 × 105; predominantly IgG1 and IgG2b) (Fig. 2D). The two surviving mice did not induce natural boosting after challenge (data not shown). i.n. immunization with GST-PyMSP119 alone induced very low titers of PyMSP119-specific antibodies (≅6 × 103; predominantly IgG1) (Fig. 2D) and conferred no protection. These results indicate that although AcNPV itself can act as a mucosal adjuvant and induce systemic antibody responses, display of PyMSP119 on the surface of the viral envelope is essential to induce protective immunity. Unlike i.n. immunization, oral immunization with AcNPV-PyMSP119surf induced low levels of PyMSP119-specific antibodies (≅4 × 104; predominantly IgG1 and IgG2b) (Fig. 2D) and conferred no protection (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Protection of BALB/c mice immunized with AcNPV-PyMSP119surf against P. yoelii challengea

| Vaccine (route) | % Maximum parasitemia | Time to clearance (days) | No. of survivors/total no. in group (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| No immunization | 75.56 ± 2.35 | 22 | 1/15 (10)b |

| AcNPV-WT (i.m.) | 74.48 ± 2.36 | 0/10 (0) | |

| AcNPV-WT (i.n.) | 72.04 ± 1.07 | 0/4 (0) | |

| AcNPV-PyMSP119surf (i.m.) | 51.09 ± 5.12 | 8.1 ± 2.0 | 7/15 (47)b |

| AcNPV-PyMSP119surf (i.n.) | 7.56 ± 3.95* | 14.7 ± 1.4** | 15/15 (100)**b |

| AcNPV-PyMSP119surf (oral) | 62.39 ± 2.51 | 0/8 (0) | |

| GST-PyMSP119 + alum (i.p.) | 37.76 ± 7.16 | 17.9 ± 3.3 | 7/15 (47)b |

| GST-PyMSP119 (i.n.) | 59.12 ± 7.27 | 0/5 (0) | |

| GST-PyMSP119 + AcNPV-WT (i.n.) | 58.67 ± 12.70 | 19.5 ± 5.5 | 2/5 (40) |

Data represent means ± SE for total mice in each group. Significant differences between the i.m. and i.n. AcNPV-PyMSP119surf groups were evaluated using Fisher's exact probability test or the Mann-Whitney U test (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01).

Cumulative data from two independent experiments.

FIG. 3.

Antibody induction in response to infection. (A) Correlation between PyMSP119-specific antibody titer and parasitemia. Mice were ranked based on maximal parasitemia (Spearman's rank correlation; r = −0.616; P = 0.0009). Crosses, death. (B) Comparison of antibody induction between days 0 and 29 postchallenge in surviving mice. A total of 22 surviving mice were from the i.m. (n = 5) and i.n. (n = 10) AcNPV-PyMSP119surf groups and the GST-PyMSP119-plus-alum (n = 7) group. PyMSP119-specific antibody titers of each group were compared between days 0 and 29. Data are means ± standard errors (SE) for the groups. Significant differences between each group were evaluated using the Mann-Whitney U test. *, P < 0.01.

Immunization with AcNPV-PyMSP119surf induces natural boosting of vaccine-induced antibodies to infection.

Determining if PyMSP119-specific antibody responses induced by immunization were boosted in response to infection was critical to our study. When parasites were cleared, the PyMSP119-specific antibody levels of the i.m. and i.n. AcNPV-PyMSP119surf groups were increased 8.0- and 8.5-fold, respectively (Fig. 3B). The PyMSP119-specific antibody titer of the i.n. AcNPV-PyMSP119surf group at day 29 was significantly higher (P = 0.014) than that of the i.m. AcNPV-PyMSP119surf group, indicating a stronger natural boosting effect by i.n. immunization. In contrast, there was no difference in the antibody levels of the GST-PyMSP119 group before and after infection. Interestingly, compared with the IgG1, -2a, and -2b isotypes, which increased 2.5- to 5-fold, IgG3 levels were elevated 11- and 36-fold for i.m. and i.n. immunization, respectively (data not shown).

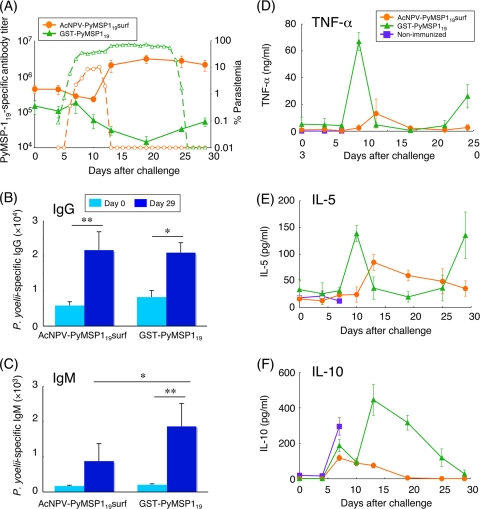

Natural boosting of PyMSP119-specific antibodies was induced during the course of infection.

To examine when natural boosting of PyMSP119-specific antibodies was induced, PyMSP119-specific antibody titers during the course of infection were determined. The kinetics of antibody titers was plotted with the course of parasitemia (Fig. 4A). PyMSP119-specific antibodies induced by i.n. immunization with AcNPV-PyMSP119surf drastically increased (eightfold) during days 10 to 13 postchallenge, coinciding with the decreasing parasitemia and parasite clearance, suggesting that the quick response of natural boosting may play critical roles in effective clearance of the parasites. In contrast, the antibody levels of the GST-PyMSP119 group gradually declined, to 10% of prechallenge levels, from days 7 to 20 postchallenge, as high levels of parasitemia were developed. This finding also supports the demonstration that PyMSP119-specific antibodies alone can control parasitemia postchallenge (31).

FIG. 4.

Antibody and cytokine responses during the course of infection. Groups of mice were immunized either i.n. with AcNPV-PyMSP119surf or i.p. with GST-PyMSP119 in alum and then challenged i.v. with 103 P. yoelii-parasitized RBC. Parasitemia was monitored daily for 4 days after challenge, and sera were collected periodically postchallenge to measure antibody titers and cytokine production. (A) Kinetics of PyMSP119-specific antibody titers and parasitemia during the course of infection. Each point for antibody titers (solid lines) represents the mean ± SD (n = 3). One representative parasitemia level for each group (dotted lines) is shown. i.n. AcNPV-PyMSP119surf data are shown in orange, and GST-PyMSP119-plus-alum data are shown in green. (B and C) IgG (B) and IgM (C) responses to blood-stage parasites at days 0 and 29. Data are means ± SE for the groups (n = 3). Significant differences between different groups were evaluated using two-tailed Fisher's exact probability test. **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05. (D to F) Kinetics of cytokine responses. Each point represents the mean ± SD (n = 3). (D) TNF-α; (E) IL-5; (F) IL-10. i.n. AcNPV-PyMSP119surf data are shown in orange, and GST-PyMSP119-plus-alum data are shown in green. Data for nonimmunized mice are shown in blue.

We further addressed the developed antiparasite antibody titers on days 0 and 29 postchallenge. The P. yoelii-specific IgG titer was significantly increased on day 29 for both groups (Fig. 4B), while P. yoelii-specific IgM was significantly elevated in the GST-PyMSP119 group but not in the i.n. AcNPV-PyMSP119surf group (Fig. 4C). These results suggest that the increasing P. yoelii-specific IgG in the i.n. AcNPV-PyMSP119surf group were mainly due to natural boosting of PyMSP119-specific antibodies against native PyMSP119 on merozoites, resulting in effective parasite clearance. The increase in P. yoelii-specific IgM in the GST-PyMSP119 group during infection was likely due to primary immune responses to parasite antigens other than PyMSP119.

For blood-stage parasites, the magnitudes, kinetics of production, and overall balance of proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines are critically important to infection outcome. We monitored cytokine expression profiles with parasitemia in immunized mice during the course of infection (Fig. 4D to F). Much lower levels of proinflammatory (TNF-α) and anti-inflammatory (IL-5 and IL-10) cytokines were induced in the sera of the i.n. AcNPV-PyMSP119surf group than in those of the GST-PyMSP119 group. Thus, i.n. immunization with AcNPV-PyMSP119surf circumvented cytokine dysregulation caused by high parasitemia.

TLR9 is involved in the mechanism of protection by i.n. immunization with AcNPV-PyMSP119surf.

To determine the role of TLR9 in the AcNPV-PyMSP119surf-induced protection, TLR9-deficient mice on a BALB/c background were immunized and challenged with P. yoelii 17XL as described above. Significantly lower levels of PyMSP119-specific antibody titers were induced in TLR9-deficient mice immunized with i.n. AcNPV-PyMSP119surf and GST-PyMSP119 in alum than in the corresponding normal BALB/c mouse groups (Fig. 5A). The IgG isotype in the i.m. and i.n. AcNPV-PyMSP119surf groups was mainly IgG1 (IgG1/IgG2a ratio ≅ 4.36 and 5.39, respectively), and IgG3 antibody was undetectable (<1:100) in any group (Fig. 5B). Thus, Th2 immune responses are induced in TLR9-deficient mice, completely contrasting with the mixed Th1/Th2-type immune responses of normal BALB/c mice shown in Fig. 2A.

FIG. 5.

PyMSP119-specific antibody response in TLR9-deficient mice. Sera were collected from individual TLR9-deficient mice (8 mice/group) 3 weeks after the last immunization and tested for PyMSP119-specific antibodies and IgG isotypes by ELISA. (A) Comparison of PyMSP119-specific antibody responses between TLR9-deficient mice and normal BALB/c mice. Data are means ± SE for the groups. Significant differences between each group were evaluated using the Mann-Whitney U test. **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05. (B) Isotype profiles of PyMSP119-specific antibodies. IgG3 was undetectable in all groups. The data represent one of two experiments, which had similar results. Data are means ± SD for the groups.

During challenge, the protection efficacy for each immunized group was almost abolished in TLR9-deficient mice (Table 2). Even though the immunized mice had high antibody titers (≥8 × 104), 82% (14/17 animals) of mice died with high parasitemia (>60%). The three surviving mice from each group did not induce natural boosting of PyMSP119-specific antibodies in response to infection.

TABLE 2.

Protection of TLR9-deficient mice immunized with AcNPV-PyMSP119surf against P. yoelii challenge

| Vaccine (route) | % Maximum parasitemiaa | Time to clearance (days) | No. of survivors/total no. in group (%) with PyMSP119-specific antibody titer |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≥8 × 104 | <8 × 104 | |||

| No immunization | 89.04 ± 0.64 | 0/7 (0) | ||

| AcNPV-WT (i.n.) | 86.80 ± 3.65 | 0/8 (0) | ||

| AcNPV-PyMSP119surf (i.m.) | 68.13 ± 9.30 | 14 | 1/2 (50) | 0/6 (0) |

| AcNPV-PyMSP119surf (i.n.)b | 69.24 ± 4.80 | 22 | 1/7 (7) | 0/8 (0) |

| GST-PyMSP119 + alum (i.p.)b | 64.16 ± 5.18 | 21 | 1/8 (7) | 0/6 (0) |

Data are means ± SE for total mice in each group. There was no significant difference between the immunized groups and the nonimmunized group, as evaluated using Fisher's exact probability test and the Mann-Whitney U test.

Cumulative data from two independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we developed a new PyMSP119 vaccine based on a baculoviral vector and highlighted natural boosting of vaccine-induced humoral immune responses during the course of infection in mice. Both i.n. AcNPV-PyMSP119surf and GST-PyMSP119 (standard recombinant PyMSP119 vaccine formulated with alum) immunizations induced high titers of PyMSP119-specific antibodies, to the same level. During the course of infection, mice immunized with AcNPV-PyMSP119surf induced natural boosting of PyMSP119-specific antibody responses shortly after challenge, coinciding with decreasing parasitemia and parasite clearance. In particular, i.n. immunization with AcNPV-PyMSP119surf conferred 100% survival with low parasitemia. Although immunization with GST-PyMSP119 in alum conferred 47% survival against challenge, the surviving mice exhibited no natural boosting of the PyMSP119-specific antibody response to infection. The results presented herein offer a novel strategy for the development of baculoviral vector-based malaria blood-stage vaccines capable of naturally boosting vaccine-induced antibody responses to infection.

The types of immune responses induced by immunization were qualitatively different between the i.n. AcNPV-PyMSP119surf and GST-PyMSP119 groups, with predominantly IgG1 and IgG2a (mixed Th1/Th2 type) and predominantly IgG1 (Th2 type) responses, respectively. In the case of the Th2-type immune response, when robust PyMSP119-specific IgG1 (noncytophilic IgG) was induced by immunization with GST-PyMSP119 in Freund's adjuvant, sterile protection was achieved without detectable parasites (28, 30). However, once parasites develop to a detectable level (∼0.1% parasitemia) in the blood, suppression of parasitemia requires newly generated immune responses to parasite antigens other than PyMSP119 responses elicited early during infection (31). This is consistent with our results showing that P. yoelii-specific IgM antibody titers, but not PyMSP119-specific IgG antibody titers, were elevated during infection in the GST-PyMSP119 group. These results suggest that although PyMSP119-specific IgG1 may function by blocking parasite invasion or inhibiting MSP1 processing, which is required for erythrocyte entry, memory B cells producing PyMSP119-specific IgG1 would be deleted from the circulation by parasite-induced apoptosis (33). The analyses of the kinetics of antibody and cytokine production during infection suggested that days 10 to 13 after challenge would be a critical turning point for subsequent parasite clearance for the i.n. AcNPV-PyMSP119surf and GST-PyMSP119 groups. The i.n. AcNPV-PyMSP119surf group induced natural boosting of vaccine-induced antibodies, resulting in rapid parasite clearance. In contrast, the GST-PyMSP119 group suffered from cytokine dysregulation caused by high parasitemia. This may trigger parasite-induced apoptosis, resulting in diminished natural boosting of PyMSP119-specific antibody responses to infection and further increasing parasitemia. In addition, induction of IgG2a and IgG2b (cytophilic IgG) antibodies may also be necessary, but not a prerequisite, for parasite clearance by the natural boosting of vaccine-induced antibody responses. Kumar et al. showed that even though immunization with recombinant PyMSP119 formulated in CpG ODN1826 emulsified in Montanide ISA 51, an adjuvant that favors Th1 differentiation, induced high levels of PyMSP119-specific IgG2a and IgG2b, no natural boosting was induced after challenge (19). These results suggest that in addition to the ability to induce a mixed Th1/Th2-type immune response, memory B cells produced by AcNPV-PyMSP119surf may possess qualitative and quantitative properties capable of resistance to parasite-induced apoptosis.

Mucosal immunization induces antigen-specific Th1- and/or Th2-type immune responses, depending on the nature of the antigen, adjuvant, and antigen delivery vehicle used. Although both i.m. and i.n. immunizations with AcNPV-PyMSP119surf induced a mixed Th1/Th2-type immune response, i.n. immunization led to higher PyMSP119-specific antibody titers and stronger natural boosting after challenge than did i.m. immunization. The i.n. immunization with GST-PyMSP119 plus AcNPV-WT induced high levels of PyMSP119-specific IgG1 and IgG2b titers and protected 40% (2/5 mice) of mice against challenge, but no natural boosting was induced. When cholera toxin B was used as a mucosal adjuvant with rPyMSP119, a Th2-type immune response (predominantly IgG1 and IgG2b) was induced, and 38% (3/8 mice) of mice were protected against challenge (14). Thus, the protection efficacy (100%) of i.n. immunization with AcNPV-PyMSP119surf was superior to those of other nasal immunization regimens. This suggests that i.n. immunization with AcNPV-PyMSP119surf displaying PyMSP119 on the surface of the viral envelope would be essential for inducing Th1 cell-derived IFN-γ production, which determines switching to IgG2a as a consequence of the cognate interaction of B cells with Th1 cells (4).

The source of Th1 cells and the precise mechanism of natural boosting are not yet defined. It is possible that i.n. immunization with AcNPV-PyMSP119surf activated DCs and macrophages, which are abundant in nasal passage-associated lymphoid tissue (NALT), a mucosal inductive site in the upper respiratory tract for humoral and cellular immune responses (36), through a TLR9-dependent pathway. In fact, AcNPV itself (composed of viral genomic DNA containing abundant CpG motifs) possesses strong adjuvant properties which can activate DC-mediated innate immunity through MyD88/TLR9-dependent and -independent pathways (1). The present study provides important insights into the roles of TLR9 following immunization with AcNPV-PyMSP119surf. In the TLR9-deficient mice immunized with AcNPV-PyMSP119surf, class switching to IgG2a was severely impaired, and natural boosting and protective efficacy were completely abolished. Jegerlehner et al. showed that IFN-γ-independent IgG2a class switching is regulated by direct TLR9 signaling in B cells (16). It is likely that AcNPV-PyMSP119surf-induced natural boosting after challenge is associated with a TLR9-dependent pathway, and direct stimulation of B cells by AcNPV-PyMSP119surf (after the second and third immunizations) could be the driving factor for class switch recombination to IgG2a in NALT. Nasal drop vaccines have several attractive features compared with parenteral vaccines (e.g., safety, cost-effectiveness, and ease of administration), but studies on their use have been limited almost exclusively to protection against mucosally transmitted pathogens. We have provided evidence that i.n. immunization is a feasible alternative for preventing malaria transmitted through nonmucosal routes. Further studies are necessary to fully understand the responses of antigen-presenting cells (APCs) in the NALT (mice) and Waldeyer's ring (humans), consisting of the adenoids and tonsils (20), to AcNPV.

Although 8 of 14 TLR9-deficient mice immunized with GST-PyMSP119 in alum had high (>8 × 104) anti-PyMSP119 antibody titers (Table 2), which are sufficient for normal mice immunized with GST-PyMSP119 to suppress parasite growth, all mice died with high parasitemia. The failure of protection suggests another role of TLR9. It has been reported that blood-stage parasites activate DCs through a TLR9-dependent pathway (27). In addition, we observed that unlike normal BALB/c mice, TLR9-deficient mice passively immunized with anti-PyMSP119 antibody died with high parasitemia when challenged with P. yoelii 17XL (data not shown). Thus, TLR9 may enhance antigen presentation by DCs, resulting in induction of antibody responses to parasite antigens during the course of infection. Further studies of TLR9-mediated memory B-cell responses to baculovirus-based vaccines and natural human malaria infection are needed.

Needle-free nasal drop immunization with the baculovirus-based vaccine provides important insights into (i) enhancement of immunogenicity of PfMSP142, (ii) strong adjuvant effects through TLR9, and (iii) subsequent natural boosting to improve current PfMSP142-based vaccine candidates.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank C. Seki and H. Nagumo for excellent assistance with the ELISAs and with handling of the mice. We also thank N. Takahashi and Y. Ishihara for help with the BioPlex system assay and with immuno-electron microscopy, respectively, and H. Matsuoka for hospitality to H.A. and T.Y.

This work was supported by grants from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports and Science of Japan (21390126).

Editor: J. H. Adams

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 9 November 2009.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://iai.asm.org/.

The authors have paid a fee to allow immediate free access to this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abe, T., H. Hemmi, H. Miyamoto, K. Moriishi, S. Tamura, H. Takaku, S. Akira, and Y. Matsuura. 2005. Involvement of the Toll-like receptor 9 signaling pathway in the induction of innate immunity by baculovirus. J. Virol. 79:2847-2858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abe, T., H. Takahashi, H. Hamazaki, N. Miyano-Kurosaki, Y. Matsuura, and H. Takaku. 2003. Baculovirus induces an innate immune response and confers protection from lethal influenza virus infection in mice. J. Immunol. 171:1133-1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burns, J. M., Jr., P. D. Dunn, and D. M. Russo. 1997. Protective immunity against Plasmodium yoelii malaria induced by immunization with particulate blood-stage antigens. Infect. Immun. 65:3138-3145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coffman, R. L., B. W. Seymour, D. A. Lebman, D. D. Hiraki, J. A. Christiansen, B. Shrader, H. M. Cherwinski, H. F. Savelkoul, F. D. Finkelman, M. W. Bond, et al. 1988. The role of helper T cell products in mouse B cell differentiation and isotype regulation. Immunol. Rev. 102:5-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daly, T. M., and C. A. Long. 1993. A recombinant 15-kilodalton carboxyl-terminal fragment of Plasmodium yoelii yoelii 17XL merozoite surface protein 1 induces a protective immune response in mice. Infect. Immun. 61:2462-2467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daly, T. M., and C. A. Long. 1995. Humoral response to a carboxyl-terminal region of the merozoite surface protein-1 plays a predominant role in controlling blood-stage infection in rodent malaria. J. Immunol. 155:236-243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Jager, W., H. te Velthuis, B. J. Prakken, W. Kuis, and G. T. Rijkers. 2003. Simultaneous detection of 15 human cytokines in a single sample of stimulated peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 10:133-139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Koning-Ward, T. F., R. A. O'Donnell, D. R. Drew, R. Thomson, T. P. Speed, and B. S. Crabb. 2003. A new rodent model to assess blood stage immunity to the Plasmodium falciparum antigen merozoite surface protein 119 reveals a protective role for invasion inhibitory antibodies. J. Exp. Med. 198:869-875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dorfman, J. R., P. Bejon, F. M. Ndungu, J. Langhorne, M. M. Kortok, B. S. Lowe, T. W. Mwangi, T. N. Williams, and K. Marsh. 2005. B cell memory to 3 Plasmodium falciparum blood-stage antigens in a malaria-endemic area. J. Infect. Dis. 191:1623-1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Egan, A. F., J. A. Chappel, P. A. Burghaus, J. S. Morris, J. S. McBride, A. A. Holder, D. C. Kaslow, and E. M. Riley. 1995. Serum antibodies from malaria-exposed people recognize conserved epitopes formed by the two epidermal growth factor motifs of MSP1(19), the carboxy-terminal fragment of the major merozoite surface protein of Plasmodium falciparum. Infect. Immun. 63:456-466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Egan, A. F., J. Morris, G. Barnish, S. Allen, B. M. Greenwood, D. C. Kaslow, A. A. Holder, and E. M. Riley. 1996. Clinical immunity to Plasmodium falciparum malaria is associated with serum antibodies to the 19-kDa C-terminal fragment of the merozoite surface antigen, PfMSP-1. J. Infect. Dis. 173:765-769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grabherr, R., W. Ernst, O. Doblhoff-Dier, M. Sara, and H. Katinger. 1997. Expression of foreign proteins on the surface of Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus. Biotechniques 22:730-735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hirunpetcharat, C., and M. F. Good. 1998. Deletion of Plasmodium berghei-specific CD4+ T cells adoptively transferred into recipient mice after challenge with homologous parasite. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:1715-1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hirunpetcharat, C., D. Stanisic, X. Q. Liu, J. Vadolas, R. A. Strugnell, R. Lee, L. H. Miller, D. C. Kaslow, and M. F. Good. 1998. Intranasal immunization with yeast-expressed 19 kDa carboxyl-terminal fragment of Plasmodium yoelii merozoite surface protein-1 (yMSP119) induces protective immunity to blood stage malaria infection in mice. Parasite Immunol. 20:413-420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hirunpetcharat, C., J. H. Tian, D. C. Kaslow, N. van Rooijen, S. Kumar, J. A. Berzofsky, L. H. Miller, and M. F. Good. 1997. Complete protective immunity induced in mice by immunization with the 19-kilodalton carboxyl-terminal fragment of the merozoite surface protein-1 (MSP119) of Plasmodium yoelii expressed in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: correlation of protection with antigen-specific antibody titer, but not with effector CD4+ T cells. J. Immunol. 159:3400-3411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jegerlehner, A., P. Maurer, J. Bessa, H. J. Hinton, M. Kopf, and M. F. Bachmann. 2007. TLR9 signaling in B cells determines class switch recombination to IgG2a. J. Immunol. 178:2415-2420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jin, R., Z. Lv, Q. Chen, Y. Quan, H. Zhang, S. Li, G. Chen, Q. Zheng, L. Jin, X. Wu, J. Chen, and Y. Zhang. 2008. Safety and immunogenicity of H5N1 influenza vaccine based on baculovirus surface display system of Bombyx mori. PLoS One 3:e3933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keitel, W. A., K. E. Kester, R. L. Atmar, A. C. White, N. H. Bond, C. A. Holland, U. Krzych, D. R. Palmer, A. Egan, C. Diggs, W. R. Ballou, B. F. Hall, and D. Kaslow. 1999. Phase I trial of two recombinant vaccines containing the 19kd carboxy terminal fragment of Plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface protein 1 (msp-119) and T helper epitopes of tetanus toxoid. Vaccine 18:531-539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kumar, S., T. R. Jones, M. S. Oakley, H. Zheng, S. P. Kuppusamy, A. Taye, A. M. Krieg, A. W. Stowers, D. C. Kaslow, and S. L. Hoffman. 2004. CpG oligodeoxynucleotide and Montanide ISA 51 adjuvant combination enhanced the protective efficacy of a subunit malaria vaccine. Infect. Immun. 72:949-957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuper, C. F., P. J. Koornstra, D. M. Hameleers, J. Biewenga, B. J. Spit, A. M. Duijvestijn, P. J. van Breda Vriesman, and T. Sminia. 1992. The role of nasopharyngeal lymphoid tissue. Immunol. Today 13:219-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Langhorne, J., F. M. Ndungu, A. M. Sponaas, and K. Marsh. 2008. Immunity to malaria: more questions than answers. Nat. Immunol. 9:725-732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luckow, V. A., and M. D. Summers. 1988. Signals important for high-level expression of foreign genes in Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus expression vectors. Virology 167:56-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matsuura, Y., R. D. Possee, H. A. Overton, and D. H. Bishop. 1987. Baculovirus expression vectors: the requirements for high level expression of proteins, including glycoproteins. J. Gen. Virol. 68:1233-1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller, L. H., T. Roberts, M. Shahabuddin, and T. F. McCutchan. 1993. Analysis of sequence diversity in the Plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface protein-1 (MSP-1). Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 59:1-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mottershead, D., I. van der Linden, C. H. von Bonsdorff, K. Keinanen, and C. Oker-Blom. 1997. Baculoviral display of the green fluorescent protein and rubella virus envelope proteins. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 238:717-722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Petritus, P. M., and J. M. Burns, Jr. 2008. Suppression of lethal Plasmodium yoelii malaria following protective immunization requires antibody-, IL-4-, and IFN-γ-dependent responses induced by vaccination and/or challenge infection. J. Immunol. 180:444-453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pichyangkul, S., K. Yongvanitchit, U. Kum-arb, H. Hemmi, S. Akira, A. M. Krieg, D. G. Heppner, V. A. Stewart, H. Hasegawa, S. Looareesuwan, G. D. Shanks, and R. S. Miller. 2004. Malaria blood stage parasites activate human plasmacytoid dendritic cells and murine dendritic cells through a Toll-like receptor 9-dependent pathway. J. Immunol. 172:4926-4933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rotman, H. L., T. M. Daly, R. Clynes, and C. A. Long. 1998. Fc receptors are not required for antibody-mediated protection against lethal malaria challenge in a mouse model. J. Immunol. 161:1908-1912. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tanabe, K., N. Sakihama, Y. Nakamura, O. Kaneko, M. Kimura, M. U. Ferreira, and K. Hirayama. 2000. Selection and genetic drift of polymorphisms within the merozoite surface protein-1 gene of Plasmodium falciparum. Gene 241:325-331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vukovic, P., K. Chen, X. Qin Liu, M. Foley, A. Boyd, D. Kaslow, and M. F. Good. 2002. Single-chain antibodies produced by phage display against the C-terminal 19 kDa region of merozoite surface protein-1 of Plasmodium yoelii reduce parasite growth following challenge. Vaccine 20:2826-2835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wipasa, J., H. Xu, M. Makobongo, M. Gatton, A. Stowers, and M. F. Good. 2002. Nature and specificity of the required protective immune response that develops postchallenge in mice vaccinated with the 19-kilodalton fragment of Plasmodium yoelii merozoite surface protein 1. Infect. Immun. 70:6013-6020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wipasa, J., H. Xu, A. Stowers, and M. F. Good. 2001. Apoptotic deletion of Th cells specific for the 19-kDa carboxyl-terminal fragment of merozoite surface protein 1 during malaria infection. J. Immunol. 167:3903-3909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wykes, M. N., Y. H. Zhou, X. Q. Liu, and M. F. Good. 2005. Plasmodium yoelii can ablate vaccine-induced long-term protection in mice. J. Immunol. 175:2510-2516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yoshida, S., M. Kawasaki, N. Hariguchi, K. Hirota, and M. Matsumoto. 2009. A baculovirus dual expression system-based malaria vaccine induces strong protection against Plasmodium berghei sporozoite challenge in mice. Infect. Immun. 77:1782-1789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yoshida, S., D. Kondoh, E. Arai, H. Matsuoka, C. Seki, T. Tanaka, M. Okada, and A. Ishii. 2003. Baculovirus virions displaying Plasmodium berghei circumsporozoite protein protect mice against malaria sporozoite infection. Virology 316:161-170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zuercher, A. W., S. E. Coffin, M. C. Thurnheer, P. Fundova, and J. J. Cebra. 2002. Nasal-associated lymphoid tissue is a mucosal inductive site for virus-specific humoral and cellular immune responses. J. Immunol. 168:1796-1803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.