Abstract

Prostaglandin E2 receptors (EP) were detected by radioligand binding in nuclear fractions isolated from porcine brain and myometrium. Intracellular localization by immunocytofluorescence revealed perinuclear localization of EPs in porcine cerebral microvascular endothelial cells. Nuclear association of EP1 was also found in fibroblast Swiss 3T3 cells stably overexpressing EP1 and in human embryonic kidney 293 (Epstein–Barr virus-encoded nuclear antigen) cells expressing EP1 fused to green fluorescent protein. High-resolution immunostaining of EP1 revealed their presence in the nuclear envelope of isolated (cultured) endothelial cells and in situ in brain (cortex) endothelial cells and neurons. Stimulation of these nuclear receptors modulate nuclear calcium and gene transcription.

Prostanoids are present in all mammalian tissues and exert a wide variety of actions via G protein-coupled receptors (1). Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), a major brain prostaglandin, has been implicated in various cerebral functions during development (2). PGE2 acts on prostaglandin E receptors EP1, EP2, EP3, and EP4; EPs are found in most tissues and are abundant in the uterus (3) and brain (4). High levels of perinatal prostaglandins arising mostly from cyclooxygenase-2 (5) were shown to result in down-regulation of plasma membrane EPs and to reduce their functional responses to barely detectable levels in the newborn neural and neurovascular tissue (2, 4); however, the actions of PGE2 in the preservation of neural function (6) and in gene transcription (7) appeared to be unaffected. Based on the predominant localization of cyclooxygenase-2 in the perinuclear envelope, it was suggested that prostanoids could act at or near their site of synthesis (8). Furthermore, a transporter that facilitates the inward movement of prostanoids recently has been cloned and characterized (9). These observations suggest possible intracellular sites of action for prostanoids. The presence of other G protein-coupled receptors on nuclei has been suggested for muscarinic (10) and angiotensin (11) receptors. Also, PGD2, its metabolite PGJ2, and PGI2, but not PGE2 or PGF2α, can activate the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors, which are members of the nuclear receptor superfamily, which includes steroid hormones (12, 13).

These observations favor the possibility that some effects of PGE2 may be mediated by EPs other than those found in the plasma membrane. We searched for the presence of nuclear EPs in a variety of cells and tissues from various species by using several experimental approaches. Our results provide evidence for the ultrastructural localization of a G protein-coupled receptor such as EP1 in the nuclear envelope of cells in culture and in situ in brain cortex; data also reveal that these receptors are functional.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Culture.

Murine Swiss 3T3 cells (American Type Culture Collection) were cultured in DMEM with 10% fetal calf serum. Human embryonic kidney (HEK293) cells (Epstein–Barr virus-encoded nuclear antigen, EBNA) (Invitrogen) were grown in hybridoma serum-free medium (HSFM) with 1% bovine calf serum. Primary cultures of porcine cerebral endothelial cells from brain microvessels (4) were established as described (14).

Materials.

AH6809 and AH23848B were gifts from Glaxo Wellcome, Stevenage, U.K., M&B 28,767 was a gift from Rhone-Poulenc Rorer, Dagenham, U.K., and Butaprost was a gift from Miles. The following products were purchased: PGE2 and 17-phenyltrinor PGE2 (Cayman Chemicals, Ann Arbor, MI); DMEM, HSFM, and geneticin (GIBCO/BRL); fetal calf serum, and goat serum (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories); and radiolabeled prostaglandins and nucleotides (Amersham). Other chemicals were from Sigma.

Animals.

Newborn pigs (1–3 days old) were killed with pentobarbital (i.c.) and tissues were removed. Tissues from adult pigs were obtained from a local abattoir.

Preparation of Subcellular Fractions.

All solutions contained 1.1 mM acetylsalicylic acid, 1 mM benzamidine, 0.2 mM phenylmethylsulfonylfluoride, and 100 μg/ml soybean trypsin inhibitor. The details for cell fractionation methods were described (11, 15, 16). Nuclei and nuclear envelopes were isolated from porcine adult myometrium (11) and newborn brain cortex (15), and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) also was isolated (16). The purity of fractions was verified by enrichment of marker enzymes 5′-nucleotidase for plasma membrane (11) and glucose-6-phosphatase for ER (17). Protein content was determined by Bio-Rad assay.

Radioligand Binding to Subcellular Fractions from Brain and Myometrium.

Saturation binding of [3H]PGE2 and [3H]PGD2 to membranes, time course of association and dissociation experiments, and displacement of [3H]PGE2 by receptor isoform-specific ligands were performed as reported (4). Receptor densities (Bmax), affinity (KD), and association (ka) and dissociation (kd) constants were determined from saturation isotherms (Prism, graphpad; ligand; ref. 18).

EP1 Receptor Expression in Swiss 3T3 Cells.

The human EP1 receptor cDNA [HindIII–XbaI fragment (19)] was cloned into the mammalian expression vector pRC-cytomegalovirus (pRC-CMV; Invitrogen). This EP1/pRC-CMV plasmid was transfected into Swiss 3T3 cells by using the calcium phosphate method (20), and geneticin (1 mg/ml)-resistant clones were selected. A clone was selected that expressed 2- to 3-fold more EP1 protein than cells transfected with vector alone (as judged by Western blotting; data not shown) and routinely cultured with geneticin.

Indirect Immunofluorescence of EP1.

For examining the immunolocalization of EP1 receptors, immunocytochemistry was performed as described (21) on Swiss 3T3, HEK293 (EBNA), or endothelial cells with rabbit anti-EP2 antibodies (22) and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated or Texas red-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (Bio/Can Scientific, Montreal) diluted 1:50. As a negative control, primary antibody was omitted or used with its cognate peptide (22). Intracellular membranes, mostly ER, were stained by using 3,3′-dihexyloxacarbocyanine iodide [DiOC6(3)], and nuclei were stained with either 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), sytox green, or propidium iodide as per instructions of the manufacturer (Molecular Probes).

Expression of EP1–Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) Fusion Protein in HEK293(EBNA) Cells.

A BamHI–XhoI cDNA fragment encoding the full-length EP1 (19) was cut at position 1,174 with FspI, resulting in the deletion of the 10 C-terminal amino acids (EP1ΔCt). The cDNA encoding the GFP S65T (23) was obtained by PCR amplification using primers containing an in-frame EcoRV site and a XhoI site at the 5′ and 3′ ends, respectively. GFP was ligated in-frame to the C terminus of EP1ΔCt in pcDNA3 expression vector (Invitrogen) linearized with BamHI and XhoI. Transient transfections were done for 6 h in 6-well plates seeded at 105 cells per well in 1.0 ml of OptiMem and transfected with 0.2 ml of OptiMem containing 750 ng of plasmid and 7.5 μl of lipofectamine. An equal volume of HSFM containing 2% bovine calf serum was added, and cells were incubated overnight. Cells were fixed with acetone/methanol (1:1) and viewed by using confocal microscopy.

Electron Microscopic Detection of EP1.

Pre-embedding immunoperoxidase and immunogold staining methods (24, 25) were used for localization of EP1 in cells and tissues. Porcine-brain endothelial cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and 0.25% glutaraldehyde, permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 for 15 min at room temperature, and incubated with anti-EP1 antibodies (1:50) overnight at 4°C. The immunoperoxidase reaction was performed by using a VectaStain ABC kit (Vector Laboratories) as per the manufacturer’s instructions, and the diaminobenzidine reaction product was intensified (25). Ultrathin sections were examined with a transmission electron microscope (Philips 410; Eindholden, The Netherlands). For immunogold staining (24), cells were fixed and incubated with anti-EP1 antibodies (1:25), followed by incubation overnight with an IgG conjugated to 1-nm gold particles diluted 1:50 (Amersham), followed by silver intensification with a silver enhancement kit (Amersham).

For detection of nuclear EP1 in vivo (25), adult rats (Sprague–Dawley) were perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde and 0.2% glutaraldehyde, and brain cortexes were subjected to rapid freeze/thawing to improve penetration of immunoreagents before Vibratome 1000 (Technical Products International, St. Louis) sectioning. Permeabilization was further enhanced by treating sections with 50% ethanol for 30 min before incubating with anti-EP1 antibodies (diluted 1:10) for 48 hr at 4°C. Subsequent steps of the technique are described above.

Nuclear Calcium Measurements.

Nuclear calcium was measured as described (14, 26) with some modifications. Isolated myometrium nuclei were resuspended in buffer (125 mM KCl/2 mM K2HPO4/25 mM Hepes/4 mM MgCl2/0.4 mM CaCl2, pH 7.0) and preloaded with 7.5 μM fura-2-acetoxymethyl for 45 min at 4°C. The nuclei were washed and stimulated (≈2 × 106 nuclei per ml) with 17-phenyltrinor PGE2 with and without AH6809 (10 μM). The intranuclear calcium concentration was measured with a spectrofluorometer (LS 50, Perkin–Elmer). Calibration of fluorescent signal was determined (14).

Dot Hybridization of RNA.

Nuclei were isolated from Swiss 3T3 cells (27). Nuclei (100 μg of protein) were incubated with or without EP1 agonist, 17-phenyltrinor PGE2 (0.1 μM) in a total volume of 40 μl for 60 min at 37°C in a 10 mM Tris⋅HCl buffer (pH 8.0) containing 5 mM MgCl2; 300 mM KCl; 0.5 mM each ATP, CTP, GTP, UTP; 111 units of RNase guard; and 10 units of DNase per reaction tube. RNA was extracted (5). For the isolation of total cytoplasmic RNA, cells were incubated with or without test agents for 1 hr and washed with ice-cold PBS. Nuclear and total RNA were applied to a nylon membrane by using a vacuum-filtration apparatus (28). 32P-labeled cDNA probes for murine c-fos (29) and β-actin (Ambion) were prepared by using an oligolabeling kit (Pharmacia); unincorporated nucleotides were removed by G-25 column chromatography. Membranes were hybridized to the radiolabeled probes and washed (28). The bands were visualized and quantified by using PhosphorImaging (Molecular Dynamics).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

[3H]PGE2 Binding to Nuclear Membranes from Porcine Brain and Myometrium.

[3H]PGE2 binding was performed on subcellular fractions of homogenates from porcine newborn brain cortex and adult myometrium. Fraction 1 contained plasma membranes, fraction 2 contained cytosol, fraction 3 contained ER, and fraction 4 contained nuclei, nuclear membranes, and some ER. Specific [3H]PGE2 binding reached equilibrium within 20 min and remained stable for another 25–30 min and was saturable and reversible as described (5). Association (ka) and dissociation (kd) constants for plasma-membrane fractions were 0.15 ± 0.04 min−1 and 0.03 ± 0.01 min−1, respectively, and for nuclear fractions were 0.09 ± 0.03 min−1 and 0.04 ± 0.01 min−1, respectively. The affinity constants for PGE2 binding were comparable in myometrium (6.3 ± 1.4 nM and 8.7 ± 2.6 nM for plasma-membrane and nuclear fractions, respectively) and newborn pig brain (9 ± 1 nM and 8.5 ± 1.2 nM for plasma-membrane and nuclear fractions, respectively). Maximum specific PGE2 binding was highest in the plasma membrane and undetectable in cytosol of adult myometrium (Table 1). In newborn brain, PGE2 binding was comparable in fractions 1, 3, and 4. PGE2 binding in nuclear fraction is not the result of contamination by plasma membranes, as indicated by negligible 5′ nucleotidase (a plasma membrane marker) activity (220 ± 13.7 and 7.0 ± 0.2 units per mg of protein in plasma-membrane and nuclear fractions, respectively). PGE2 binding to nuclear envelope and to intact nuclei was comparable; nuclear extracts devoid of nuclear membranes did not bind PGE2 (data not shown).

Table 1.

Maximum specific binding on cell fractions

| Tissue | PG | PM | ER | NM | CYT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uterus | PGE2 | 58 ± 4 | 37 ± 4 | 23 ± 3 | ud |

| PGD2 | 36 ± 3 | 2 ± 0.4 | ud | nd | |

| Brain | PGE2 | 13 ± 3 | 13 ± 1 | 12 ± 3 | ud |

| PGD2 | 21 ± 1 | ud | 15 ± 1 | nd |

Values (Bmax in fmol/mg protein) are the mean ± SEM of three experiments performed in duplicate. PM, plasma membrane; NM, nuclear membrane; CYT, cytosol; ud, undetectable (<0.1 fmol/mg protein); nd, not determined.

Unlike the distribution of PGE2 binding in various fractions derived from both brain and myometrial tissue, PGD2 specific binding was minimal-to-undetectable in fraction 3 (ER) derived from both brain and myometrium, whereas nuclear membrane (fraction 4) from brain but not from myometrium displayed PGD2 binding (Table 1). As expected, ER contiguous with the outer nuclear membrane (30) was found in fraction 4, as indicated by glucose-6-phosphatase (ER marker) specific activity (9.5 ± 3.2, 23.1 ± 2.2, and 19.2 ± 1.4 mmol of PO4 released per mg of protein in fractions 1, 3, and 4, respectively). Hence, prostaglandin binding detected in nuclear membranes cannot be simply caused by contamination by the ER.

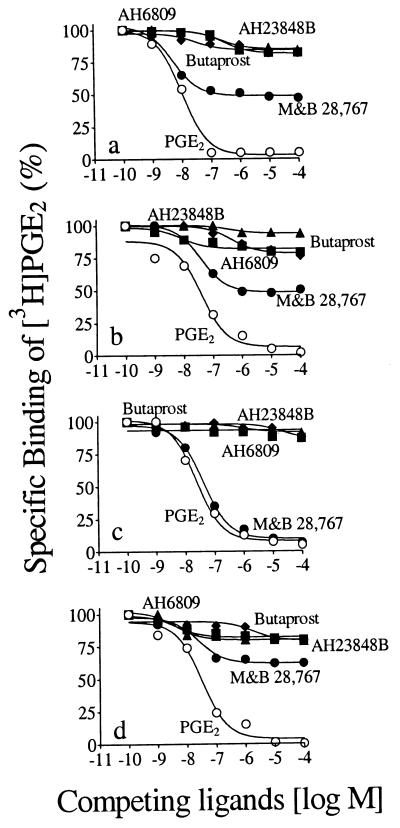

Displacement of [3H]PGE2 by receptor subtype ligands, AH6809 (EP1 antagonist), butaprost (EP2-selective agonist), M&B 28,767 (EP3-selective agonist), and AH23848B (EP4 antagonist) revealed the presence of all EP subtypes in both plasma-membrane and nuclear-membrane fractions of myometrium, albeit EP3 was the most abundant (50%; Fig. 1 a and b). In plasma-membrane fractions of newborn brain, EP3 accounted for all EP receptors (Fig. 1c), whereas in nuclear membranes, EP3 comprised 45% of total EPs, and the balance was evenly distributed among EP1, EP2, and EP4 (Fig. 1d).

Figure 1.

Competitive displacement of [3H]PGE2 binding to subcellular fractions from porcine adult myometrium and newborn brain by prostaglandins and analogs: fractions 1 (a) and 4 (b) from myometrium and fractions 1 (c) and 4 (d) from brain. Fraction 1 contained plasma membrane and fraction 4 contained nuclear membrane. Membranes were incubated with 10 nM [3H]PGE2 and increasing concentrations of prostaglandins and analogs. ○, PGE2; ■ AH6809; ♦, Butaprost; •, M&B 28,767; ▴, AH23848B. Each point is mean ± SE of three experiments, in duplicate.

Intracellular Localization of EP1 in HEK 293(EBNA) Cells.

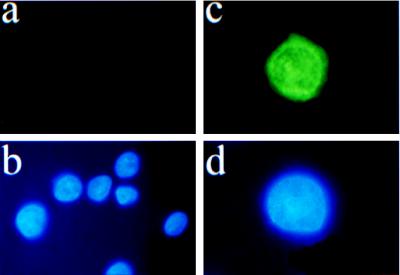

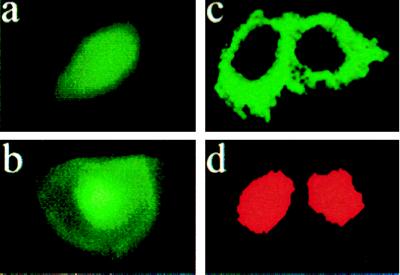

There are many isoforms of EP3 (31); because specific antibodies or selective pharmacological ligands for these isoforms are not available, we did not conduct further studies of this receptor. On the other hand, the clear displacement of bound [3H]PGE2 by EP1 antagonist AH6809 on nuclear fractions of two distinct tissues, brain and myometrium (Fig. 1 b and d), and the availability of specific anti-EP1 antibodies (22) led us to focus our investigation on the cellular localization of EP1 receptors. In HEK 293(EBNA) cells, which do not naturally express EP1 receptors (32) and subsequently are stably transfected with human EP1 cDNA (33), EP1 immunoreactivity was distributed in the cytoplasm and perinuclear areas (Fig. 2c); no immunoreactivity was detected in the wild-type cells (Fig. 2a), which confirms specificity of the EP1 antibodies.

Figure 2.

EP1 immunofluorescence of ectopically expressed human EP1 receptor in HEK293(EBNA) cells. (a) Cells transfected with vector alone; note the absence of fluorescence. (b) Nuclear stain (DAPI) of cells from a. (c) An EP1-overexpressing clone; note the perinuclear halo. (d) Nuclear stain (DAPI) of cells from c.

Intracellular Localization of EP1 by Indirect Immunofluorescence.

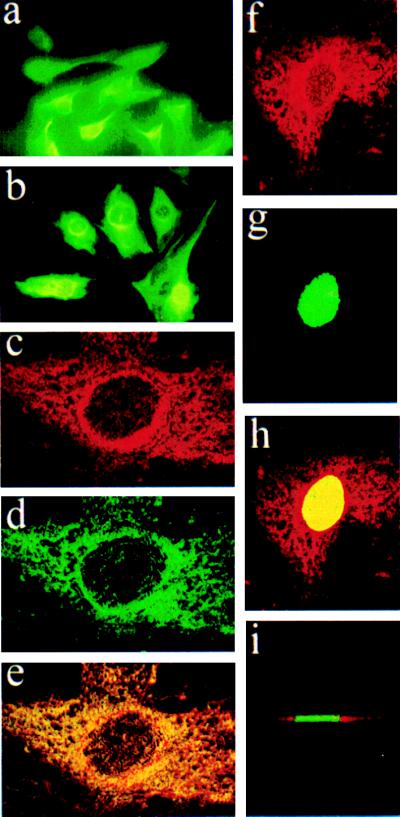

On murine fibroblast Swiss 3T3 cells overexpressing the EP1 receptor, EP1-specific immunofluorescence was distributed in the cytoplasm (Fig. 4 a and b), although an intensified halo surrounding the nucleus was seen in transfected cells (Fig. 4b). Confocal microscopy of these EP1-overexpressing 3T3 cells and also of cerebral microvascular endothelial cells (primary culture) revealed a distribution of the receptor throughout the cytoplasm concentrated in the perinuclear region (Fig. 3 a and b; Fig. 4 c and d). EP1 antibody and intracellular membrane stains were partially superimposed, as revealed by the yellow and orange speckles (Figs. 3c and 4e). Confocal microscopic images were also obtained for EP1-overexpressing cells stained with the nuclear stain, Sytox green (Fig. 4g). Superimposition of EP1 immunofluorescence (Fig. 4f) with nuclear staining (Sytox green; Fig. 4g) disclosed colocalization (bright yellow nucleus) of EP1 immunoreactivity in the nuclear/perinuclear region (Fig. 4h); a Z-section of these cells indicated that EP1-specific fluorescence was limited to perinuclear and surrounding regions, but was not found within the nucleus (Fig. 4i).

Figure 4.

EP1 immunofluorescence of ectopically expressed EP1 receptor in murine Swiss 3T3 cells: (a) Cells transfected with vector alone. (b) EP1-overexpressing clone; note the intense perinuclear halo. Confocal microscopic images of EP1 overexpressing cells. (c) Anti-EP1 antibody and Texas red-conjugated IgG. (d) DiOC6(3), intracellular membranes (mostly ER) stain. (e) Superimposed images of c and d. (f) Anti-EP1 antibody and Texas red-conjugated IgG. (g) Sytox green nucleus stain. (h) Superimposed images of f and g. (i) Z section of h.

Figure 3.

Confocal microscopic images of EP1 immunostaining in porcine cerebromicrovascular endothelial cells. (a) Anti-EP1 antibody and Texas red-conjugated IgG. (b) DiOC6(3), intracellular membranes (mostly endoplasmic reticulum) stain. (c) superimposed images of a and b. (d) Anti-EP1 in the presence of cognate peptide (10 μg/ml) and nuclear stain (propidium iodide); note the absence of immunostaining.

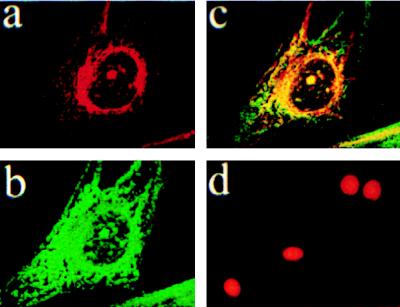

Distribution of EP1 Fused to GFP.

GFP from the jellyfish Aequorea victoria has been used as a fluorescent tag to study the intracellular localization of G protein-coupled receptors such as the β2-adrenergic receptors (34). The protein fusions to either β2-adrenergic receptors (34) or to human EP1 (Y.D., unpublished results) did not interfere with receptor functions such as ligand binding, G-protein coupling, or activation of second messengers. HEK 293(EBNA) cells were transiently transfected with an EP1–GFP construct, and the intracellular localization of the fusion protein was visualized. Nuclear (optical microscopy) and more specifically perinuclear (confocal microscopy) localization of EP1–GFP protein was observed in transfected cells (Fig. 5 b and c); in cells transfected with GFP alone, fluorescence was diffusely distributed in the cytoplasm (Fig. 5a). In contrast, β2-adrenergic receptor tagged to GFP was shown to exhibit primarily plasma-membrane labeling without perinuclear localization (34).

Figure 5.

GFP protein localization in transfected HEK293(EBNA) cells. a and b are optical fluorescent microscopic images and c and d are confocal images. (a) GFP alone; note the diffuse staining pattern. (b and c) EP1–GFP fusion protein; perinuclear halo at higher confocal magnification (c). (d) Nuclear stain (propidium iodide) of cells from b.

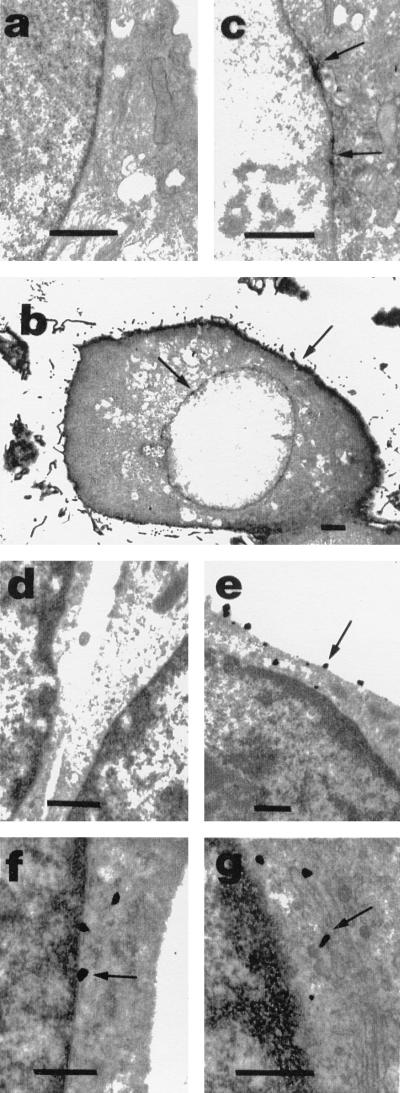

Detection of EP1 Immunoreactivity by Electron Microscopy.

Radioligand binding, immunofluorescence identification of native EP1 protein in endothelial and fibroblast cells, cloned EP1 expressed in fibroblasts, and use of EP1–GFP fusion protein revealed a prominent localization of EP1 receptor in the perinuclear area. To discern the nuclear envelope, high-resolution studies of cultured newborn pig cerebral microvessel endothelial cells and of adult rat brain cortex were done. In cultured endothelial cells, the immunoperoxidase and immunogold methods revealed EP1-specific immunostaining in the plasma membrane (Fig. 6 b and e), the nuclear envelope (Fig. 6 c and f), the Golgi apparatus (Fig. 6g), and vesicles (not shown). No immunostaining was detected in the ER.

Figure 6.

Immunoperoxidase and immunogold localization of EP1 in porcine endothelial cells detected by electron microscopy (arrows). (a) Immunoperoxidase-IgG alone; note absence of immunostaining when primary antibody is omitted. (b) A low magnification showing immunostaining in plasma membrane and nuclear envelope. (c) A higher magnification showing immunostaining in the nuclear envelope. (d) Immunogold-IgG alone; note absence of immunostaining. Specific immunostaining can be observed in the plasma membrane in e, nuclear envelope in f, and Golgi apparatus in g. (Bar = 0.5 μm, except in b = 2 μm.)

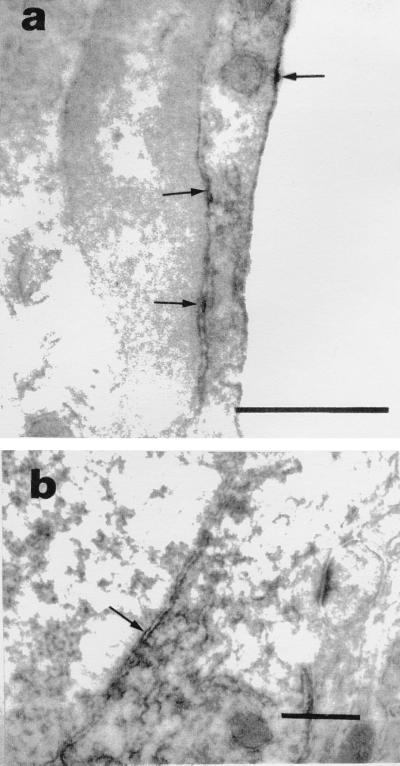

To verify that the localization of EP1 in the nuclear envelope was not only a newborn and/or an in vitro characteristic, sections from adult rat cerebral cortex were examined. EP1 immunostaining was seen in inner and outer nuclear membranes of endothelial cells (Fig. 7a) and neurons (Fig. 7b).

Figure 7.

Immunoperoxidase localization of EP1 in adult rat brain cortex by electron microscopy (arrows). Specific immunostaining observed in plasma membrane and inner and outer nuclear membranes of capillary endothelial cell (a) and nuclear membranes of neurons (b). Note the luminal space of capillary on right in a. (Bars = 0.5 μm.)

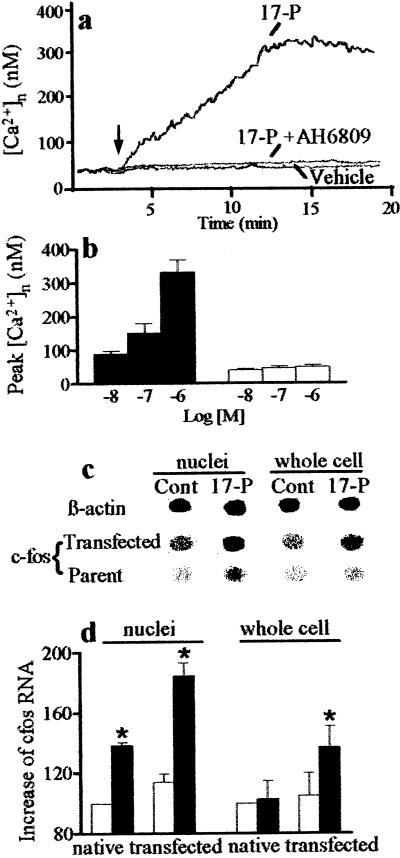

Effects of Nuclear EP1 Stimulation on Modulation of Nuclear Calcium and Gene Transcription.

Nuclear membranes contain a variety of intermediate factors involved in EP-mediated signal transduction, such as G proteins (35), calcium channels, and Ca2+-ATPase (36). The nuclear envelope serves as a pool for calcium and has been proposed to regulate nuclear calcium signals (37). We therefore tested whether nuclear EP1 are capable of eliciting a function such as affecting calcium entry directly into isolated nuclei. As shown (Fig. 8 a and b), 17-phenyltrinor PGE2 (EP1 agonist) caused a concentration-dependent increase in myometrial intranuclear calcium concentration; this effect was abrogated by EP1 antagonist AH6809.

Figure 8.

Effects of EP1 agonist, 17-phenyltrinor PGE2 (17-P) and AH6809 (EP1 antagonist, 10 μM) on calcium levels in isolated myometrial nuclei loaded with fura-2 AM (a and b). (a) Typical tracings; arrow shows time of compound or vehicle administration; 17-P (1 μM). (b) Peak increases in intranuclear calcium concentrations [(Ca2+)n] after addition of 17-P (filled bars) or 17-P and AH6809 (10 μM; open bars). Effects of 17-phenyltrinor PGE2 (0.1 μM) on c-fos transcription in native and EP1 over-expressing Swiss 3T3 cells as measured by dot blot hybridization of RNA. (c) Dot blot; Cont, control without drug. β-actin dot blot is of parent cells; its intensity was unaffected by EP1 cDNA transfection. (d) Densitometry of dot blots; c-fos RNA abundance corrected for β-actin RNA is expressed as percentage of native untreated controls (open bar). Data are means ± SE of three experiments. ∗, P < 0.05 compared with the corresponding control.

Calcium has been implicated to play an important role in nuclear functions, including the regulation of gene transcription (37) such as c-fos (38), which also has been shown to be stimulated by PGE2 (39). We tested whether the stimulation of nuclear EP1 with prostaglandin analogs affects c-fos transcription. Dot hybridization of RNA revealed that exposure of nuclei from Swiss 3T3 cells to EP1 agonist 17-phenyltrinor PGE2 (0.1 μM) increased transcription of c-fos to a greater extent than that observed after stimulation of whole cells; this effect was augmented in cells overexpressing EP1 (Fig. 8 c and d) and was abolished by AH6809 (10 μM; not shown).

In conclusion, the present study provides evidence for the existence of the prostaglandin receptor EP1 in the perinuclear region from various species by numerous techniques and most notably in the nuclear envelope in cell lines and in vivo in tissues, as revealed by high-resolution studies. This report shows an ultrastructural localization of a functional G protein-coupled receptor in the nuclear envelope. The presence of nuclear AT1 receptors that contain a nuclear localization sequence has been detected by radioligand binding (11) and immunoreactivity, mostly after pharmacological stimulation with angiotensin II (40). A nuclear localization sequence was not found in EP1 receptor (19). So far, other than the EP1 variant lacking all C-terminal tail (41) and thus undetectable with our antibody (22), no other EP1 have been identified (42). The similarity in the kinetics of PGE2 binding and antibody recognition of EP1 receptors in both plasma and nuclear membranes, matching localization of ectopically expressed EP1 receptor and EP1–GFP fusion protein, as well as pharmacological characteristics and comparable molecular weights [as determined by immunoblotting, which showed a single 65-kDa EP1 immunoreactive band (data not shown)] indicates that the receptors in both cellular compartments are of similar identity. Finally, the presence of nuclear EPs provides an explanation for actions of PGE2 when plasma membrane EPs are barely detectable (4, 6, 7). In addition, consistent with the localization of cyclooxygenase-2 in the perinuclear region (8), it is conceivable that locally generated prostaglandins can activate nuclear EPs that can in turn modulate gene transcription, as recently speculated (43); details of transduction mechanisms remain to be elucidated in this action of prostaglandins via nuclear EP receptors.

Acknowledgments

We thank H. Fernandez and M. Ballak for their technical assistance and A. Mcleod and S. Grant for sharing their expertise. M.B. is a recipient of the Doctoral Research Award from the Medical Research Council of Canada (MRC). This study was supported by grants from the MRC.

ABBREVIATIONS

- PG

prostaglandin

- EP

PG receptors

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- EBNA

Epstein–Barr virus-encoded nuclear antigen

- HEK

human embryonic kidney

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the Proceedings Office.

References

- 1.Campbell W, Halushka P. In: Goodman & Gilman′s: The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. Hardman J, Limbird L, editors. New York: McGraw–Hill; 1996. pp. 601–616. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chemtob S, Li D Y, Abran D, Hardy P, Peri K, Varma D. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1996;85:517–524. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1996.tb14077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robertson R P. Prostaglandins. 1986;31:395–411. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(86)90105-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li D Y, Varma D, Chemtob S. Br J Pharmacol. 1994;112:59–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1994.tb13029.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peri K, Hardy P, Li D Y, Varma D, Chemtob S. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:24615–24620. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.41.24615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doke A, Hardy P, Peri K, Molotchnikoff S, Varma D, Lachapelle P, Roy M-S, Chemtob S. Pediatr Res. 1996;39:205A. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dumont I, Peri K, Abran D, Hardy P, Molotchnikoff S, Varma D, Chemtob S. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:R1812–R1821. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1998.275.6.R1812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morita I, Schindler M, Regier M, Otto J C, Hori T, DeWitt D, Smith W. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:10902–10908. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.18.10902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kanai N, Run L, Satriano J, Yi B, Wolkoff A, Schuster V. Science. 1995;268:866–869. doi: 10.1126/science.7754369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lind G, Cavanagh H. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1993;34:2943–2952. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Booz G, Conra K, Hess A, Singer H, Baker K. Endocrinology. 1992;130:3641–3649. doi: 10.1210/endo.130.6.1597161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kliewer S, Lenhard J, Willson T, Patel I, Morris D, Lehmann J. Cell. 1995;83:813–819. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90194-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hertz R, Berman I, Keppler D, Bar-Tana J. Eur J Biochem. 1996;235:242–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.00242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lahaie I, Hardy P, Hou X, Hassessian H, Asselin P, Lachapelle P, Almazan G, Varma D, Morrow J, Jackson Roberts L, Chemtob S. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:1406–1416. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1998.274.5.R1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rubin B, Fox T, Bridges R. Brain Res. 1986;383:60–67. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)90008-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Croze E, Morre D J. J Cell Physiol. 1984;119:46–57. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041190109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Noordlie R, Arion W. Methods Enzymol. 1966;9:619–625. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Munson P, Rodbard D. Anal Biochem. 1980;107:220–239. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(80)90515-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Funk C, Furci L, FitzGerald G, Grygorczk R, Rochette C, Bayne M, Abramovitz M, Adam M, Metters K. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:26767–26772. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sambrook J, Fritsch E, Maniatis T. In: Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Nolan C, editor. Plainview, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press; 1989. pp. 16.32–16.36. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Figueiredo B, Almazan G, Ma Y, Tetzlaff W, Miller F, Cuello A. Mol Brain Res. 1993;17:258–268. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(93)90010-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhao C, Fujimoto N, Shichi H. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 1995;11:421–435. doi: 10.1089/jop.1995.11.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heim R, Prasher D, Tsien R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:12501–12504. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.26.12501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pickel V, Chan J, Aoki C. In: Immunohistochemistry. Cuello A, editor. New York: Wiley; 1993. pp. 265–280. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ribeiro-da-Silva A, Priestly J, Cuello A. In: Immunohistochemistry. Cuello A, editor. New York: Wiley; 1993. pp. 181–227. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nicotera P, McConkey D, Jones D, Orrenius S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:453–457. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.2.453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Greenberg M, Ziff E. Nature (London) 1984;311:433–437. doi: 10.1038/311433a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sambrook J, Fritsch E, Maniatis T. In: Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manua. Nolan C, editor. Plainview, New York: Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press; 1989. pp. 9.52–9.55. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van Beveren C, Van Straaten T, Curran T, Muller R, Verma I. Cell. 1983;32:1241–1255. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90306-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dale B, DeFelice L, Kyozuka K, Santella L, Tosti E. Proc R Soc London Ser B. 1994;255:119–124. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Namba T, Sugimoto Y, Negishi M, Irie A, Ushikubi F, Kakizuka A. Nature (London) 1993;365:166–170. doi: 10.1038/365166a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boie Y, Stocco R, Sawyer N, Slipetz D, Ungrin M, Neuschafer-Rube F, Puschel G, Metters K, Abramovitz M. Eur J Pharmacol. 1997;340:227–241. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01383-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abramovitz, M., Adam, A., Boie, Y., Godbout, C., Lamontagne, S., Rochette, C., Sawyer, N., Tremblay, N., Belley, M., Gallant, M., et al. (1999) Biochim. Biophys. Acta, in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Barak L S, Ferguson S, Zhang J, Martenson C, Meyer T, Caron M. Mol Pharmacol. 1997;51:177–184. doi: 10.1124/mol.51.2.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saffitz J, Nash J, Green K, Luke R, Ransnas L, Insel P. FASEB J. 1994;8:252–258. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.8.2.8119495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Humbert J, Matter N, Artault J, Pascal K, Malviya A. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:478–485. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.1.478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Malviya A, Rogue P. Cell. 1998;92:17–23. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80895-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hardingham G, Chawla S, Johnson C, Bading H. Nature (London) 1997;385:260–265. doi: 10.1038/385260a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Danesch U, Weber P, Sellmayer A. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:27258–27263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lu D, Yang H, Shaw G, Raizada M. Endocrinology. 1998;139:365–375. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.1.5679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Okuda-Ashitaka E, Sakamoto K, Ezashi T, Miwa K, Ito S, Hayaishi O. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:31255–31261. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.49.31255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pierce K, Regan J. Life Sci. 1997;62:1479–1483. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(98)00093-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Goetzl E, An S, Smith W. FASEB J. 1995;9:1051–1058. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.9.11.7649404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]