Abstract

Hepatitis C virus (HCV)-specific CD8+ T cells in persistent HCV infection are low in frequency and paradoxically show a phenotype associated with controlled infections, expressing the memory marker CD127. We addressed to what extent this phenotype is dependent on the presence of cognate antigen. We analyzed virus-specific responses in acute and chronic HCV infections and sequenced autologous virus. We show that CD127 expression is associated with decreased antigenic stimulation after either viral clearance or viral variation. Our data indicate that most CD8 T-cell responses in chronic HCV infection do not target the circulating virus and that the appearance of HCV-specific CD127+ T cells is driven by viral variation.

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) persists in the majority of acutely infected individuals, potentially leading to chronic hepatitis, liver cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma. The cellular immune response has been shown to play a significant role in viral control and protection from liver disease. Phenotypic and functional studies of virus-specific T cells have attempted to define the determinants of a successful versus an unsuccessful T-cell response in viral infections (10). So far these studies have failed to identify consistent distinguishing features between a T-cell response that results in self-limiting versus chronic HCV infection; similarly, the impact of viral persistence on HCV-specific memory T-cell formation is poorly understood.

Interleukin-7 (IL-7) receptor alpha chain (CD127) is a key molecule associated with the maintenance of memory T-cell populations. Expression of CD127 on CD8 T cells is typically only observed when the respective antigen is controlled and in the presence of significant CD4+ T-cell help (9). Accordingly, cells specific for persistent viruses (e.g., HIV, cytomegalovirus [CMV], and Epstein-Barr virus [EBV]) have been shown to express low levels of CD127 (6, 12, 14) and to be dependent on antigen restimulation for their maintenance. In contrast, T cells specific for acute resolving virus infections, such as influenza virus, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), hepatitis B virus (HBV), and vaccinia virus typically acquire expression of CD127 rapidly with the control of viremia (5, 12, 14). Results for HCV have been inconclusive. The expected increase in CD127 levels in acute resolving but not acute persisting infection has been found, while a substantial proportion of cells with high CD127 expression have been observed in long-established chronic infection (2). We tried to reconcile these observations by studying both subjects with acute and chronic HCV infection and identified the presence of antigen as the determinant of CD127 expression.

Using HLA-peptide multimers we analyzed CD8+ HCV-specific T-cell responses and CD127 expression levels in acute and chronic HCV infection. We assessed a cohort of 18 chronically infected subjects as well as 9 individuals with previously resolved infection. In addition, we longitudinally studied 9 acutely infected subjects (5 individuals who resolved infection spontaneously and 4 individuals who remain chronically infected) (Tables 1 and 2). Informed consent in writing was obtained from each patient, and the study protocol conformed to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki, as reflected in a priori approval from the local institutional review boards. HLA-multimeric complexes were obtained commercially from Proimmune (Oxford, United Kingdom) and Beckman Coulter (CA). The staining and analysis procedure was as described previously (10). Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were stained with the following antibodies: CD3 from Caltag; CD8, CD27, CCR7, CD127, and CD38 from BD Pharmingen; and PD-1 (kindly provided by Gordon Freeman). Primer sets were designed for different genotypes based on alignments of all available sequences from the public HCV database (http://hcvpub.ibcp.fr). Sequence analysis was performed as previously described (8).

TABLE 1.

Patient information and autologous sequence analysis for patients with chronic and resolved HCV infection

| Code | Genotype | Status | Epitope(s) targeted | Sequencea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 02-03 | 1b | Chronic | A1 NS3 1436-1444 | P: ATDALMTGY |

| A: no sequence | ||||

| 00-26 | 1b | Chronic | A1 NS3 1436-1444 | P: ATDALMTGY |

| A: no sequence | ||||

| 99-24 | 2a | Chronic | A2 NS3 1073-1083 | P: CINGVCWTV |

| No recognition | A: S-S--L--- | |||

| A2 NS3 1406-1415 | P: KLVALGINAV | |||

| No recognition | A: A-RGM-L--- | |||

| A2 NS5B 2594-2602 | P: ALYDVVTKL | |||

| A: no sequence | ||||

| 111 | 1a | Chronic | A2 NS3 1073-1083 | P: CINGVCWTV |

| A: --------- | ||||

| A2 NS5 2594-2602 | P: ALYDVVTKL | |||

| A: --------- | ||||

| 00X | 3a | Chronic | A2 NS5 2594-2602 | P: ALYDVVTKL |

| No recognition | A: -----IQ-- | |||

| O3Qb | 1a | Chronic | A1 NS3 1436-1444 | P: ATDALMTGY |

| Diminished | A: --------F | |||

| 03Sb | 1a | Chronic | A1 NS3 1436-1444 | P: ATDALMTGY |

| Diminished | A: --------F | |||

| 02A | 1a | Chronic | A1 NS3 1436-1444 | P: ATDALMTGY |

| A: no sequence | ||||

| 01N | 1a | Chronic | A1 NS3 1436-1444 | P: ATDALMTGY |

| Diminished | A: --------F | |||

| 03H | 1a | Chronic | A2 NS3 1073-1083 | P: CINGVCWTV |

| Full recognition | A: ----A---- | |||

| 01-39 | 1a | Chronic | A1 NS3 1436-1444 | P: ATDALMTGY |

| Diminished | A: --------F | |||

| 03-45b | 1a | Chronic | A1 NS3 1436-1444 | P: ATDALMTGY |

| Diminished | A: --------F | |||

| 06P | 3a | Chronic | A1 NS3 1436-1444 | P: ATDALMTGY |

| Diminished | A: --------F | |||

| GS127-1 | 1a | Chronic | A2 NS3 1073-1083 | P: CINGVCWTV |

| A: --------- | ||||

| GS127-6 | 1a | Chronic | A2 NS3 1073-1083 | P: CINGVCWTV |

| A: --------- | ||||

| GS127-8 | 1b | Chronic | A2 NS3 1073-1083 | P: CINGVCWTV |

| A: --------- | ||||

| GS127-16 | 1a | Chronic | A2 NS3 1073-1083 | P: CINGVCWTV |

| A: --------- | ||||

| GS127-20 | 1a | Chronic | A2 NS3 1073-1083 | P: CINGVCWTV |

| A: --------- | ||||

| 04D | 4 | Resolved | A2 NS5 1987-1996 | P: VLSDFKTWKL |

| 01-49b | 1 | Resolved | A2 NS5 1987-1996 | P: VLSDFKTWKL |

| A2 NS3 1406-1415 | P: KLVALGINAV | |||

| 01-31 | 1 | Resolved | A1 NS3 1436-1444 | P: ATDALMTGY |

| B57 NS5 2629-2637 | P: KSKKTPMGF | |||

| 04N | 1 | Resolved | A1 NS3 1436-1444 | P: ATDALMTGY |

| 01E | 4 | Resolved | A2 NS5 1987-1996 | P: VLSDFKTWKL |

| 98A | 1 | Resolved | A2 NS3 1073-1083 | P: CINGVCWTV |

| 00-10c | 1 | Resolved | A24 NS4 1745-1754 | P: VIAPAVQTNW |

| O2Z | 1 | Resolved | A1 NS3 1436-1444 | P: ATDALMTGY |

| 99-21 | 1 | Resolved | B7 CORE 41-49 | P: GPRLGVRAT |

| OOR | 1 | Resolved | B35 NS3 1359-1367 | P: HPNIEEVAL |

P, prototype; A, autologous. Identical residues are shown by dashes.

HIV coinfection.

HBV coinfection.

TABLE 2.

Patient information and autologous sequence analysis for patients with acute HCV infection

| Code | Genotype | Outcome | Epitope targeted and time analyzed | Sequencea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 554 | 1a | Persisting | A2 NS3 1073-1083 | P: CINGVCWTV |

| wk 8 | A: --------- | |||

| wk 30 | A: --------- | |||

| 03-32 | 1a | Persisting | B35 NS3 1359-1367 | P: HPNIEEVAL |

| wk 8 | A: --------- | |||

| No recognition (wk 36) | A: S-------- | |||

| 04-11 | 1a (1st) | Persisting (1st) Resolving (2nd) | A2 NS5 2594-2602 | P: ALYDVVTKL |

| 1b (2nd) | A: no sequence | |||

| 0023 | 1b | Persisting | A1 NS3 1436-1444 | P: ATDALMTGY |

| Diminished (wk 7) | A: --------F | |||

| Diminished (wk 38) | A: --------F | |||

| A2 NS3 1073-1083 | P: CINGVCWTV | |||

| wk 7 | A: --------- | |||

| wk 38 | A: --------- | |||

| A2 NS3 1406-1415 | P: KLVALGINAV | |||

| Full recognition (wk 7) | A: --S------- | |||

| Full recognition (wk 38) | A: --S------- | |||

| 320 | 1 | Resolving | A2 NS3 1273-1282 | P: GIDPNIRTGV |

| 599 | 1 | Resolving | A2 NS3 1073-1083 | P: CINGVCWTV |

| 1144 | 1 | Resolving | A2 NS3 1073-1083 | P: CINGVCWTV |

| B35 NS3 1359-1367 | P: HPNIEEVAL | |||

| 06L | 3a | Resolving | B7 CORE 41-49 | P: GPRLGVRAT |

| 05Y | 1 | Resolving | A2 NS3 1073-1083 | P: CINGVCWTV |

P, prototype; A, autologous. Identical residues are shown by dashes.

In established persistent infection, CD8+ T-cell responses against HCV are infrequently detected in blood using major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I tetramers and are only observed in a small fraction of those sampled (10). We were able to examine the expression of CD127 on antigen-specific T cells in such a group of 18 individuals. We observed mostly high levels of CD127 expression (median, 66%) on these populations (Fig. 1a), although expression was higher on HCV-specific T-cell populations from individuals with resolved infection (median, 97%; P = 0.0003) (Fig. 1a and c). Importantly, chronically infected individuals displayed CD127 expression levels over a much broader range than resolved individuals (9.5% to 100% versus 92 to 100%) (Fig. 1a).

FIG. 1.

Chronically infected individuals express a range of CD127 levels on HCV-specific T cells. (a) CD127 expression levels on HCV-specific T-cell populations in individuals with established chronic or resolved infection. While individuals with resolved infection (11 tetramer stains in 9 subjects) uniformly express high levels of CD127, chronically infected individuals (21 tetramer stains in 18 subjects) express a wide range of CD127 expression levels. (b) CD127 expression levels are seen to be highly dependent on sequence match with the autologous virus, based on analysis of 9 responses with diminished recognition of the autologous virus and 8 responses with intact epitopes. (c) CD127 expression levels on HCV-specific T-cell B7 CORE 41-49-specific T cells from individual 01-49 with resolved HCV infection (left-hand panel). Lower CD127 expression levels are observed on an EBV-specific T-cell population from the same individual (right-hand panel). APC-A, allophycocyanin-conjugated antibody. (d) Low CD127 levels are observed on A2 NS3 1073-1083 HCV-specific T cells from individual 111 with chronic HCV infection in whom sequencing revealed an intact autologous sequence.

Given the relationship between CD127 expression and antigenic stimulation as well as the potential of HCV to escape the CD8 T-cell response through viral mutation, we sequenced the autologous circulating virus in subjects with chronic infection (Table 1). A perfect match between the optimal epitope sequence and the autologous virus was found for only 8 responses. These were the only T-cell populations with lower levels of CD127 expression (Fig. 1a, b, and d). In contrast, HCV T-cell responses with CD127 expression levels comparable to those observed in resolved infection (>85%) were typically mismatched with the viral sequence, with some variants compatible with viral escape and others suggesting infection with a non-genotype 1 strain (10) (Fig. 1). Enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) assays using T-cell lines confirmed the complete abrogation of T-cell recognition and thus antigenic stimulation in cases of cross-genotype mismatch (10). Responses targeting the epitope A1-143D expressed somewhat lower levels of CD127 (between 70% and 85%). Viral escape (Y to F at position 9) in this epitope has been shown to be associated with significantly diminished but not fully abolished recognition (11a), and was found in all chronically infected subjects whose T cells targeted this epitope. Thus, expression of CD127 in the presence of viremia is closely associated with the capacity of the T cell to recognize the circulating virus.

That a decrease in antigenic stimulation is indeed associated with the emergence of CD127-expressing CD8 T cells is further demonstrated in subject 111. This subject with chronic infection targeted fully conserved epitopes with T cells with low CD127 expression; with clearance of viremia under antiviral therapy, CD127-negative HCV-specific CD8 T cells were no longer detectable and were replaced by populations expressing CD127 (data not shown). Overall these data support the notion that CD127 expression on HCV-specific CD8+ T-cell populations is dependent on an absence of ongoing antigenic stimulation.

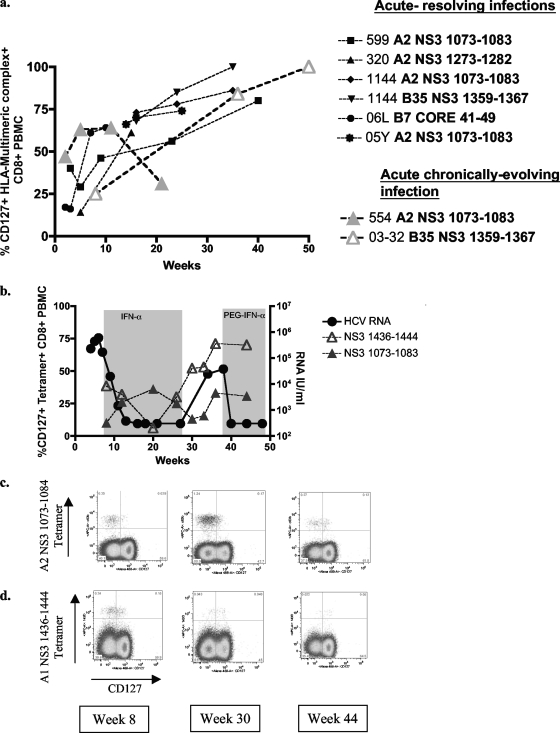

To further evaluate the dynamic relationship between antigenic stimulation and CD127 expression, we also analyzed HCV-specific T-cell responses longitudinally during acute HCV infection (Fig. 2a). CD127 expression was generally low or absent during the earliest time points. After resolution of infection, we see a contraction of the HCV-specific T-cell response together with a continuous increase in CD127 expression, until virtually all tetramer-positive cells express CD127 approximately 6 months after the onset of disease (Fig. 2a). A similar increase in CD127 expression was not seen in one subject (no. 554) with untreated persisting infection that maintained a significant tetramer-positive T-cell population for an extended period of time (Fig. 2a). Importantly, sequence analysis of the autologous virus demonstrated the conservation of this epitope throughout persistent infection (8). In contrast, subject 03-32 (with untreated persisting infection) developed a CD8 T-cell response targeting a B35-restricted epitope in NS3 from which the virus escaped (8). The T cells specific for this epitope acquired CD127 expression in a comparable manner to those controlling infection (Fig. 2a). In other subjects with persisting infection, HCV-specific T-cells usually disappeared from blood before the time frame in which CD127 upregulation was observed in the other subjects.

FIG. 2.

CD127 expression levels during acute HCV infection. (a) CD127 expression levels on HCV-specific T cells during the acute phase of HCV infection (data shown for 5 individuals who resolve and two individuals who remain chronically infected). (b) HCV RNA viral load and CD127 expression levels on HCV-specific T cells (A2 NS3 1073-1083 and A1 NS3 1436-1444) for chronically infected individual 00-23. PEG-IFN-α, pegylated alpha interferon. (c) Fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) plots showing longitudinal CD127 expression levels on HCV-specific T cells (A2 NS3 1073-1083 and A1 NS3 1436-1444) from individual 00-23.

We also characterized the levels of CD127 expression on HCV-specific CD4+ T-cell populations with similar results: low levels were observed during the acute phase of infection and increased levels in individuals after infection was cleared (data not shown). CD127 expression on CD4 T cells could not be assessed in viral persistence since we failed to detect significant numbers of HCV-specific CD4+ T cells, in agreement with other reports.

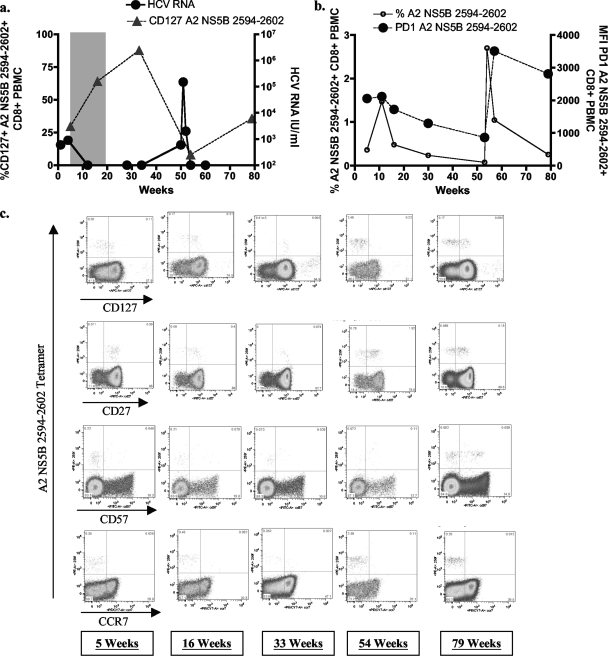

In our cohort of subjects with acute HCV infection, we had the opportunity to study the effect of reencounter with antigen on T cells with high CD127 expression in 3 subjects in whom HCV viremia returned after a period of viral control. Subject 00-23 experienced viral relapse after interferon treatment (11), while subjects 05-13 and 04-11 were reinfected with distinct viral isolates. In all subjects, reappearance of HCV antigen that corresponded to the HCV-specific T-cell population was associated with massive expansion of HCV-specific T-cell populations and a decrease in CD127 expression on these T cells (Fig. 2 and 3) (data not shown). In contrast, T-cell responses that did not recognize the current viral isolate did not respond with an expansion of the population or the downregulation of CD127. This was observed in 00-23, where the sequence of the A1-restricted epitope 143D was identical to the frequent escape mutation described above in chronically infected subjects associated with diminished T-cell recognition (Fig. 2b and 3a). In 05-13, the viral isolate during the second episode of viremia contained a variant in one of the anchor residues of the epitope A2-61 (Fig. 2d). These results show that CD127 expression on HCV-specific T cells follows the established principles observed in other viral infections.

FIG. 3.

Longitudinal phenotypic changes on HCV-specific T cells. (a) HCV RNA viral load and CD127 expression (%) levels on A2 NS5B 2594-2602 HCV-specific T cells for individual 04-11. This individual was administered antiviral therapy, which resulted in a sustained virological response. Following reinfection, the individual spontaneously cleared the virus. (b) Longitudinal frequency of A2 NS5B 2594-2602 HCV-specific T cells and PD-1 expression levels (mean fluorescent intensity [MFI]) for individual 04-11. (c) Longitudinal analysis of 04-11 reveals the progressive differentiation of HCV-specific A2 259F CD8+ T cells following repetitive antigenic stimulation. FACS plots show longitudinal CD127, CD27, CD57, and CCR7 expression levels on A2 NS5B 2594-2602 tetramer-positive cells from individual 04-11. PE-A, phycoerthrin-conjugated antibody.

In addition to the changes in CD127 expression for T cells during reencounter with antigen, we detected comparable changes in other phenotypic markers shortly after exposure to viremia. First, we detected an increase in PD-1 and CD38 expression—both associated with recent T-cell activation. Additionally, we observed a loss of CD27 expression, a feature of repetitive antigenic stimulation (Fig. 3). The correlation of CD127 and CD27 expression further supports the notion that CD127 downregulation is a marker of continuous antigenic stimulation (1, 7).

In conclusion we confirm that high CD127 expression levels are common for detectable HCV-specific CD8+ T-cell populations in chronic infection and find that this phenotype is based on the existence of viral sequence variants rather than on unique properties of HCV-specific T cells. This is further demonstrated by our data from acute HCV infection showing that viral escape as well as viral resolution is driving the upregulation of CD127. We also show that some, but not all, markers typically used to phenotypically describe virus-specific T cells show a similar dependence on cognate HCV antigen. Our data further highlight that sequencing of autologous virus is vital when interpreting data obtained in chronic HCV infection and raise the possibility that previous studies, focused on individuals with established chronic infection, may have been confounded by antigenic variation within epitopes or superinfection with different non-cross-reactive genotypes. Interestingly, it should be pointed out that this finding is supported by previous data from both the chimpanzee model of HCV and from human HBV infection (3, 13).

Overall our data clearly demonstrate that the phenotype of HCV-specific CD8+ T cells is determined by the level of antigen-specific stimulation. The high number of CD127 positive virus-specific CD8+ T cells that is associated with the presence of viral escape mutations is a hallmark of chronic HCV infection that clearly separates HCV from other chronic viral infections (4, 14).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

Sequence data are available from GenBank under accession no. EF032883, EF032885, EF032887, EF032889, EU781777, EU781780, EU781799, GU117907, GU117908, GU117911, GU117912, GU117915-GU117919, and GU117921-GU117925.

Acknowledgments

We thank Allyson Bloom for critical help with finalizing the manuscript.

The work presented here was supported by the National Institutes of Health (U19-AI066345 to G.M.L., L.L.-X., T.M.A., and A.Y.K. and RO1-AI067926-01 to T.M.A.) and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG SCHU 2482/1-1 to J.S.Z.W.).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 11 November 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Appay, V., P. R. Dunbar, M. Callan, P. Klenerman, G. M. Gillespie, L. Papagno, G. S. Ogg, A. King, F. Lechner, C. A. Spina, S. Little, D. V. Havlir, D. D. Richman, N. Gruener, G. Pape, A. Waters, P. Easterbrook, M. Salio, V. Cerundolo, A. J. McMichael, and S. L. Rowland-Jones. 2002. Memory CD8+ T cells vary in differentiation phenotype in different persistent virus infections. Nat. Med. 8:379-385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bengsch, B., H. C. Spangenberg, N. Kersting, C. Neumann-Haefelin, E. Panther, F. von Weizsacker, H. E. Blum, H. Pircher, and R. Thimme. 2007. Analysis of CD127 and KLRG1 expression on hepatitis C virus-specific CD8+ T cells reveals the existence of different memory T cell subsets in the peripheral blood and liver. J. Virol. 81:945-953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bertoletti, A., A. Costanzo, F. V. Chisari, M. Levrero, M. Artini, A. Sette, A. Penna, T. Giuberti, F. Fiaccadori, and C. Ferrari. 1994. Cytotoxic T lymphocyte response to a wild type hepatitis B virus epitope in patients chronically infected by variant viruses carrying substitutions within the epitope. J. Exp. Med. 180:933-943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blattman, J. N., E. J. Wherry, S. J. Ha, R. G. van der Most, and R. Ahmed. 2009. Impact of epitope escape on PD-1 expression and CD8 T cell exhaustion during chronic infection. J. Virol. 83:4386-4394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boettler, T., E. Panther, B. Bengsch, N. Nazarova, H. C. Spangenberg, H. E. Blum, and R. Thimme. 2006. Expression of the interleukin-7 receptor alpha chain (CD127) on virus-specific CD8+ T cells identifies functionally and phenotypically defined memory T cells during acute resolving hepatitis B virus infection. J. Virol. 80:3532-3540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Foxwell, B. M., D. A. Taylor-Fishwick, J. L. Simon, T. H. Page, and M. Londei. 1992. Activation induced changes in expression and structure of the IL-7 receptor on human T cells. Int. Immunol. 4:277-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hamann, D., P. A. Baars, M. H. Rep, B. Hooibrink, S. R. Kerkhof-Garde, M. R. Klein, and R. A. van Lier. 1997. Phenotypic and functional separation of memory and effector human CD8+ T cells. J. Exp. Med. 186:1407-1418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuntzen, T., J. Timm, A. Berical, L. L. Lewis-Ximenez, A. Jones, B. Nolan, J. Schulze zur Wiesch, B. Li, A. Schneidewind, A. Y. Kim, R. T. Chung, G. M. Lauer, and T. M. Allen. 2007. Viral sequence evolution in acute hepatitis C virus infection. J. Virol. 81:11658-11668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lang, K. S., M. Recher, A. A. Navarini, N. L. Harris, M. Lohning, T. Junt, H. C. Probst, H. Hengartner, and R. M. Zinkernagel. 2005. Inverse correlation between IL-7 receptor expression and CD8 T cell exhaustion during persistent antigen stimulation. Eur. J. Immunol. 35:738-745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lauer, G. M., E. Barnes, M. Lucas, J. Timm, K. Ouchi, A. Y. Kim, C. L. Day, G. K. Robbins, D. R. Casson, M. Reiser, G. Dusheiko, T. M. Allen, R. T. Chung, B. D. Walker, and P. Klenerman. 2004. High resolution analysis of cellular immune responses in resolved and persistent hepatitis C virus infection. Gastroenterology 127:924-936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lauer, G. M., M. Lucas, J. Timm, K. Ouchi, A. Y. Kim, C. L. Day, J. Schulze zur Wiesch, G. Paranhos-Baccala, I. Sheridan, D. R. Casson, M. Reiser, R. T. Gandhi, B. Li, T. M. Allen, R. T. Chung, P. Klenerman, and B. D. Walker. 2005. Full-breadth analysis of CD8+ T-cell responses in acute hepatitis C virus infection and early therapy. J. Virol. 79:12979-12988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11a.Neumann-Haefelin, C., D. N. Frick, J. J. Wang, O. G. Pybus, S. Salloum, G. S. Narula, A. Eckart, A. Biezynski, T. Eiermann, P. Klenerman, S. Viazov, M. Roggendorf, R. Thimme, M. Reiser, and J. Timm. 2008. Analysis of the evolutionary forces in an immunodominant CD8 epitope in hepatitis C virus at a population level. 82:3438-3451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Leeuwen, E. M., G. J. de Bree, E. B. Remmerswaal, S. L. Yong, K. Tesselaar, I. J. ten Berge, and R. A. van Lier. 2005. IL-7 receptor alpha chain expression distinguishes functional subsets of virus-specific human CD8+ T cells. Blood 106:2091-2098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weiner, A., A. L. Erickson, J. Kansopon, K. Crawford, E. Muchmore, A. L. Hughes, M. Houghton, and C. M. Walker. 1995. Persistent hepatitis C virus infection in a chimpanzee is associated with emergence of a cytotoxic T lymphocyte escape variant. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 92:2755-2759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wherry, E. J., C. L. Day, R. Draenert, J. D. Miller, P. Kiepiela, T. Woodberry, C. Brander, M. Addo, P. Klenerman, R. Ahmed, and B. D. Walker. 2006. HIV-specific CD8 T cells express low levels of IL-7Ralpha: implications for HIV-specific T cell memory. Virology 353:366-373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]