Abstract

Several variants of APOBEC3H (A3H) have been identified in different human populations. Certain variants of this protein are particularly potent inhibitors of retrotransposons and retroviruses, including HIV-1. However, it is not clear whether HIV-1 Vif can recognize and suppress the antiviral activity of A3H variants, as it does with other APOBEC3 proteins. We now report that A3H_Haplotype II (HapII), a potent inhibitor of HIV-1 in the absence of Vif, can indeed be degraded by HIV-1 Vif. Vif-induced degradation of A3H_HapII was blocked by the proteasome inhibitor MG132 and a Cullin5 (Cul5) dominant negative mutant. In addition, Vif mutants that were incapable of assembly with the host E3 ligase complex factors Cul5, ElonginB, and ElonginC were also defective for A3H_HapII suppression. Although we found that Vif hijacks the same E3 ligase to degrade A3H_HapII as it does to inactivate APOBEC3G (A3G) and APOBEC3F (A3F), more Vif motifs were involved in A3H_HapII inactivation than in either A3G or A3F suppression. In contrast to A3H_HapII, A3H_Haplotype I (HapI), which differs in only three amino acids from A3H_HapII, was resistant to HIV-1 Vif-mediated degradation. We also found that residue 121 was critical for determining A3H sensitivity and binding to HIV-1 Vif.

The apolipoprotein B mRNA-editing catalytic polypeptide 3 (APOBEC3) protein family is composed of cytidine deaminases that are capable of editing nucleic acids, converting cytidines to uracils (2, 12, 15, 18, 26, 27, 31, 45, 82, 91). Members of this family of host cell proteins (APOBEC3A, -B, -C, -DE, -F, -G, and -H) have been shown to have differential inhibitory effects on various retroviruses and retroelements that are mediated through cytidine deamination and other mechanisms (4, 7, 8, 10, 13, 14, 19, 20, 22, 23, 25, 37-41, 43, 46, 48, 55, 57-59, 63, 71, 72, 75, 77, 79, 81, 89, 93, 94, 98).

In the absence of the HIV-1 protein Vif, APOBEC3G (A3G), like other APOBEC3 proteins, can be packaged into newly formed HIV-1 virions. Upon infection of new target cells, the packaged A3G induces C-to-U modifications in the newly reverse-transcribed minus-strand viral DNA, resulting in hypermutation of the viral genome (30, 40, 48, 78, 90, 94). Virion-packaged A3G has also been reported to suppress viral activity by inhibiting reverse transcription and integration and/or by inducing viral DNA degradation (3, 5, 28, 35, 43, 50, 54, 56, 69, 70, 88).

HIV-1 Vif is able to neutralize the antiviral activity of multiple APOBEC3 proteins by hijacking the host's ubiquitin-proteasome system (16, 36, 48, 49, 51, 73, 76, 92). This viral protein assembles with the host Cullin5-ElonginB-ElonginC E3 ligase complex (92) and polyubiquitinates APOBEC3 proteins for subsequent proteasome-mediated degradation (16, 42, 49, 51, 73, 76, 92). Mutational studies have shown that Vif interacts with ElonginB-ElonginC and Cullin5 through the S144LQxLA149 and H108x5Cx17-18Cx3-5H139 motifs located in the C terminus of Vif (44, 51, 52, 83-85, 92, 93). HIV-1 Vif may also inhibit A3G function through degradation-independent mechanisms (60).

Various motifs in the amino-terminal domain of HIV-1 Vif are responsible for its specific targeting of different APOBEC3 proteins (9, 32, 49, 53, 64, 68, 74, 80). For example, several positively charged amino acids from position 22 to 44 are important for Vif-mediated suppression of A3G but not of A3F (9, 21, 53, 64, 74, 87, 96). In contrast, amino acids 11 to 17 and 74 to 79 of Vif are crucial for the Vif-mediated suppression of A3F but not A3G (32, 64, 68, 74, 80). In addition, a highly conserved hydrophobic motif, V52xIPLx4-5LxΦx2YWxL72, in Vif is important for the suppression of both A3G and A3F (32, 61). Other APOBEC3 family members, such as A3C and A3DE, are also subject to Vif-mediated degradation and are recognized by Vif through a mechanism similar to that for A3F (9, 97).

A3H lies distal to A3G on chromosome 22 (17, 31, 60), and it is the only APOBEC3 protein discovered thus far that contains a single copy of a Z3-type APOBEC3 catalytic domain (40) previously termed Z2 type (17). It encodes a conserved cytidine deaminase and is capable of inducing mutation in prokaryotes (19, 29, 58, 59). A3H mRNA has been detected in several human tissues, including peripheral blood mononuclear cells, and is moderately upregulated in macrophages by interferons (29, 58, 59, 79). When transfected into mammalian cells, it is insufficiently expressed and has weak antiretroviral activity (59). However, when a higher level of A3H expression in mammalian cells was achieved by using a cytomegalovirus (CMV) intron A-containing expression vector, A3H was found to have strong anti-HIV-1 activity (19, 29).

Several single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were identified in the A3H gene. As first reported by OhAinle and colleagues (58, 59), the Single Nucleotide Polymorphism database at NCBI (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/SNP) shows that there are six nonsynonymous SNPs (R18L, G37H, G105R, K121E/D, S140G, and E178D) and two single-codon deletions (Δ14N and Δ15N) for the human A3H gene. Four haplotypes were reported to be circulating in the human population (29, 58, 95), as follows: HapI, 18R/105G/121K/178E; HapII, 18R/105R/121D/E/178D; HapIII, d15N/18R/105R/121D/E/178D; and HapIV, d15N/18L/105R/121D/E/178D. APOBEC3H variant NM_181773 (Ensembl no. ENS 00000100298) has served as a wild-type reference and was designated HapI (58). Intriguingly, A3H_HapII, differing by only three amino acids from A3H_HapI (G105R/K121D/E/E178D), is more stable than the other three haplotypes and is reported to have the strongest inhibitory effect on both HIV-1 and Line-1 transposition (19, 29, 58, 95).

However, whether A3H can be suppressed by HIV-1 Vif remains controversial. While it has been argued that both HapI and HapII A3H have strong anti-HIV-1 activity and are insensitive to Vif degradation (19, 29), OhAinle et al. have reported that A3H_HapII is the only A3H variant with strong antiviral activity whose anti-HIV-1 activity is significantly decreased in the presence of Vif (58). It is also unknown whether HIV-1 Vif suppresses A3H_HapII by ubiquitin-proteasome mediated degradation, as is true for A3G.

In the present study, we demonstrate that HIV-1 Vif does indeed interact with A3H_HapII and induces proteasome-mediated degradation through a mechanism similar to that responsible for A3G degradation. We have also found that the interaction between A3H_HapII and Vif is mediated through specific substrate recognition domains of Vif that are distinct from those for the human A3G and A3F proteins. In contrast to the susceptibility of A3H_HapII, we found that A3H_HapI is insensitive to Vif-mediated degradation and is less stable than A3H_HapII. A single amino acid change, G105R, in HapI greatly stabilized the protein and increased its antiviral activity against HIV-1. However, HapI_G105R was still unable to bind or be degraded by HIV-1 Vif. Finally, we also found that amino acid 121 of A3H was a critical determinant of resistance or susceptibility to HIV-1 Vif inactivation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids.

Infectious molecular clones of wild-type (WT) HIV-1pNL4-3 and NL4-3ΔVif were obtained from the AIDS Research Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health. pCMV-A3H_HapI_V5 was a kind gift of Y. H. Zheng, Michigan State University. hA3H_HapI_G105R, hA3H_HapI_K121E, hA3H_HapI_E178D, hA3H_HapI_G105R/K121E, and hA3H_HapI_G105R/K121E/E178D were generated by site-directed mutagenesis using the following primer sets: hA3H-G105R-forward, GACCATCTGAACCTGCGTATCTTCGCCTCCCGC; hA3H-G105R-reverse, GCGGGAGGCGAAGATACGCAGGTTCAGATGGTC; hA3H-K121E-forward, TGCAAGCCCCAGCAGGAAGGACTGCGGCTTCTG; hA3H-K121E-reverse, CAGAAGCCGCAGTCCTTCCTGCTGGGGCTTGCA; hA3H-E178D-forward, AAGCGACGGCTAGACAGGATAAAGCAGTC; and hA3H-E178D-reverse, GACTGCTTTATCCTGTCTAGCCGTCGCTT.

Plasmids pVifDR14/15AA, pVifRH41/42AA, pVifS53A, pVifV55S, pVifI57S, pVifP58A, pVifL59S, pVifL64S, pVifI66S, pVifY69A, pVifW70A, pVifL72S, pVifT74A, pVifE76A, pVifR77A, and pVifW79A were made from pHIV-1 Vif-myc and have been described previously (32).

Cell culture and antibodies.

293T and MAGI-CCR5 (AIDS Research Reagents Program) cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Invitrogen) with 10% fetal bovine serum and 25 μg/ml gentamicin (Sigma) and transfected or infected as previously described (92). The following antibodies were used as previously described (96): anti-HA monoclonal antibody (MAb) (Covance, MMS-101R-10000), anti-myc MAb (Sigma, M5546), and antiactin MAb (Sigma, A3853). The anti-Vif antibody was obtained from the AIDS Research Reagents Program (2221), mouse anti-V5 antibody was from Invitrogen (R96025), rabbit anti-V5 was from Covance (PRB-198P), and rabbit anti-green fluorescent protein (anti-GFP) antibody was from Abcam (ab6556-25).

Transfection, viral infectivity (MAGI), assays and virus purification.

Transfection was performed with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) as instructed by the manufacturer. The viral infectivity (MAGI) assay was performed as previously described (92). In brief, virus was produced by transfecting 293T cells in a six-well plate with 1.5 μg of NL4-3 or NL4-3ΔVif and with 1.5 μg of A3H expression vector or an empty vector as a control. Virus was harvested from the supernatant, and cells were reserved for immunoblotting to monitor A3H degradation. Infectivity was assessed at 48 h postinfection and normalized to the input CAp24 detected by anti-p24 antibody (obtained from the AIDS Research Reagents Program). To purify virus, cell culture supernatants were cleared of cellular debris by centrifugation at 3,000 rpm for 15 min in a Sorvall RT 6000B centrifuge and filtration through a 0.2-μm-pore-size membrane (Millipore). Virus particles were then concentrated by centrifugation through a 20% sucrose cushion by ultracentrifugation at 100,000 × g for 1.5 h at 4°C in a Sorvall Ultra80 ultracentrifuge. Viral pellets were resuspended in lysis buffer (phosphate-buffered saline [PBS] containing 1% Triton X-100 and Complete protease inhibitor cocktail [Roche]) and analyzed by immunoblotting.

Immunoprecipitation and immunoblot analysis.

293T cells were harvested at 48 h after transfection, washed with PBS, and lysed in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris [pH 7.5] with 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, and Complete protease inhibitor cocktail tablets) at 4°C for 30 min, followed by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 30 min. Hemagglutinin (HA) tag immunoprecipitation was carried out by mixing cell lysates from a T25 flask with a 25-μl bead volume of anti-HA antibody-conjugated agarose beads (Roche) and incubating the mixture at 4°C for 3 h. myc tag immunoprecipitation was carried out by mixing precleared cell lysate with anti-myc antibody (Upstate) and incubating with protein G at 4°C for 3 h. Samples were washed six times with washing buffer (20 mM Tris [pH 7.5] with 100 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, and 0.05% Tween 20). The beads were then eluted with 2× loading buffer. The eluted materials were then analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with the appropriate antibodies. The anti-HA antibody-agarose conjugate and anti-HA antibody used have been previously described (96).

Modeling.

Homology modeling of the N-terminal domain of A3G (A3G-NTD) and A3H_HapII was carried out using both the program Modeler (66) and the automated modeling server I-TASSER (96), which has been ranked as the best server in the recent CASP7 and CASP8 modeling contests (1). Modeler and I-TASSER produced very similar models, suggesting convincing modeling results. Modeling by Modeler was carried out in the following steps. Prior to the modeling, multiple-sequence alignment was carried out for APOBEC2, the amino-terminal domain of A3G (A3G-NTD), the carboxyl-terminal domain of A3G (A3G-CTD), and A3H_HapII by using the program MUSCLE (24). The available crystal structures of two homologous APOBECs, APOBEC2 (62) and A3G-CTD (11, 33), were then used to validate and improve the alignment manually. Subsequently, the aligned sequences of A3G-NTD/A3H_HapII, APOBEC2, and A3G-CTD were input into Modeler for homology modeling using the crystal structures of both APOBEC2 (Protein Data Bank [PDB] no. 2NYT) and A3G-CTD (PDB no. 3E1U) as multiple templates, which improved the quality of the modeling. This step was carried out using the built-in functionality of Modeler by inputting both PDB files as “knowns.” Confidence in the homology modeling is imparted by (i) the high degree of sequence homology between A3H_HapII, A3G-NTD, and the template proteins and (ii) the similarity of the resulting models produced by Modeler and I-TASSER. The resulting model is reliable especially for the highly conserved regions in which the motif RLYYFW and A3H_HapII residues 105, 121, and 178 are located.

RESULTS

A3H_HapII can be inactivated by HIV-1 Vif.

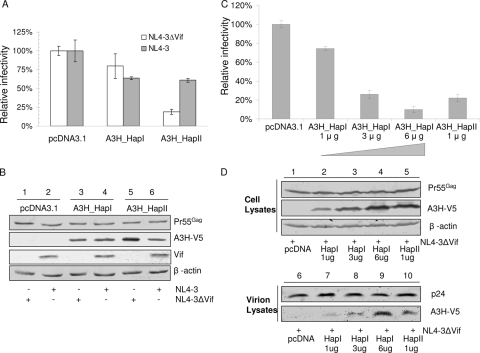

It is still controversial whether A3H can be inactivated by HIV-1 Vif (19, 29, 58). To assess the antiviral activity of A3H and its sensitivity to Vif, we cotransfected empty vector or V5-tagged A3H_HapI or A3H_HapII together with NL4-3 or NL4-3ΔVif into 293T cells and tested the infectivity of the virus produced using MAGI assays. In the absence of Vif, we found that A3H_HapI demonstrated weak anti-HIV-1 activity, whereas A3H_HapII showed a significantly higher level of anti-HIV-1 activity (Fig. 1A). In agreement with previous reports (29, 59), we observed higher expression levels of transfected A3H_HapII than of A3H_HapI in the absence of Vif (Fig. 1B, compare lanes 3 and 5).

FIG. 1.

A3H_HapII has strong anti-HIV-1 activity which is suppressed by HIV-1 Vif. (A) NL4-3 and NL4-3ΔVif viruses were produced in 293T cells cotransfected with either NL4-3 or NL4-3ΔVif plus an APOBEC3H expression vector (A3H_HapI or A3H_HapII) or empty control vector. After 48 h, virus was collected and assayed for virus infectivity using MAGI indicator cells. Relative infectivity was expressed as a percentage of the infectivity obtained in the absence of APOBEC3 (i.e., with the empty vector control, pcDNA3.1). Error bars indicate standard deviations. (B) Virus-producing 293T cells were harvested and analyzed by SDS-PAGE, followed by immunoblotting, to detect intracellular levels of A3H proteins. β-Actin was used as a loading control. (C) Comparison of the antiviral activities of increasing amounts of A3H_HapI with A3H_HapII. (D) Comparison of the intracellular expression and virion packaging of increasing amounts of A3H_HapI with A3H_HapII.

Interestingly, we found that in the presence of the Vif protein, the virus-restricting ability of A3H_HapII was decreased (Fig. 1A). We also observed lower A3H_HapII protein levels in cells transfected with NL4-3 than in those transfected with NL4-3 ΔVif (Fig. 1B, compare lanes 5 and 6). In contrast, the A3H_HapI protein levels were the same in the absence or presence of HIV-1 Vif (Fig. 1B, compare lanes 3 and 4). These results indicate that both A3H_HapII activity and the steady-state levels of A3H_HapII are decreased by exposure to Vif.

To examine whether weaker antiviral activity of A3H_HapI is due to its reduced expression compared to that of A3H_HapII, we compared the antiviral activity, intracellular expression, and virion packaging of increasing amounts of A3H_HapI versus A3H_HapII. We found that the antiviral activity of A3H_HapI and A3H_HapII was directly correlated to the cellular expression level of the protein. When comparable intracellular levels of A3H_HapI and A3H_HapII were achieved, A3H_HapI and A3H_HapII had similar antiviral activity against HIV-1 (Fig. 1C). Furthermore, virion packaging was also correlated to the intracellular expression levels of A3H_HapI and A3H_HapII (Fig. 1D).

Vif targets A3H_HapII for proteasome-mediated degradation.

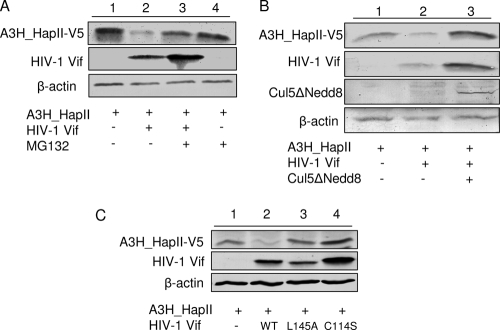

To determine whether A3H_HapII activity and protein levels are decreased as a result of Vif-mediated degradation in proteasomes, we expressed A3H_HapII and myc-tagged wild-type Vif or empty vector in 293T cells. At 36 h posttransfection, the cells were treated with proteasome inhibitor MG132 for 16 h or left untreated. In the presence of Vif, the protein level of A3H_HapII was significantly reduced when MG132 was not present (Fig. 2A, compare lanes 1 and 2); however, the protein level of A3H_HapII was restored in the cells that were treated with MG132 (Fig. 2A, compare lanes 2 and 3), suggesting that Vif-mediated degradation of A3H_HapII occurs via proteasomal cleavage. We also observed an increased expression of Vif in the cells treated with MG132, suggesting that Vif is also degraded by proteasomes (Fig. 2A).

FIG. 2.

Vif hijacks Cul5/ElongBC E3 ligase and suppresses A3H_HapII by inducing its proteasomal degradation. (A) 293T cells were cotransfected with 1 μg of A3H_HapII and 3 μg of wild-type Vif. At 36 h posttransfection, the cells were treated with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or with MG132 for 16 h. Cell lysates were harvested and analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting to detect A3H_HapII, with β-actin as the loading control. (B) A dominant negative Cul5 mutant (Cul5ΔNedd8) blocks Vif-induced A3H_HapII degradation. 293T cells were cotransfected with 1 μg of A3H_HapII plus 3 μg of empty vector, wild-type HIV-1 Vif, or wild-type HIV-1 Vif plus Cul5ΔNedd8. Cell were harvested at 48 h posttransfection and analyzed by SDS-PAGE, followed by immunoblotting to detect A3H_HapII, with β-actin as the loading control. (C) 293T cells were cotransfected with 1 μg of A3H_HapII and with 3 μg of empty vector, wild-type HIV-1 Vif, or mutant VifL145A or VifC114S. Cells were harvested at 48 h posttransfection and analyzed by SDS-PAGE, followed by immunoblotting to detect A3H_HapII, with β-actin as the loading control.

To further elucidate the mechanism of Vif-mediated degradation of A3H_HapII, we cotransfected A3H and Vif with Cul5 dominant negative mutant Cul5ΔNedd8 (92). As shown in Fig. 2B, when Vif was cotransfected with A3H_HapII, the A3H_HapII protein level was decreased (lane 2) compared to that in its absence (lane 1). However, in the presence of Cul5ΔNedd8, Vif's ability to decrease A3H_HapII expression was blocked (Fig. 2B, compares lanes 2 and 3). We also tested the BC box mutant VifL145A and zinc binding domain mutant VifC114S, which are deficient in binding to either Cullin5 or ElonginB-ElonginC. These mutants fail to form a virus-specific E3 ligase and cannot inactivate A3G (44, 93). Expression plasmids expressing wild-type Vif, VifL145A, VifC114S, or empty vector were cotransfected with A3H_HapII into 293T cells. In the presence of wild-type Vif, we saw a decrease in the level of A3H_HapII protein in the cell lysate as a result of proteasome-mediated degradation (Fig. 2C, compare lanes 2 and 1); however, the A3H_HapII protein level in the presence of mutant Vif proteins was unchanged compared to the control value (Fig. 2C, compare lanes 3 and 4 to 1). These data indicated that HIV-1 Vif can suppress A3H_HapII through the recruitment of the Cul5-EloB/C E3 ubiquitin ligase and proteasomes.

Identification of distinct regions of HIV-1 Vif that are required for A3H_HapII suppression.

Various domains of HIV-1 Vif are responsible for its specific interaction with diverse APOBEC3 proteins (Fig. 3A). The substrate binding domains for A3G or A3F are distinctly different (9, 32, 49, 53, 61, 64, 68, 74, 80, 97). Two domains of HIV-1 Vif, the F1 box (W11xxDRMR17) and the F2 box (T74GERxW79), are important only for A3F inactivation. A patch of positively charged residues from amino acid 22 to 44 of Vif (the G box) is mainly important for A3G inactivation. Furthermore, a hydrophobic motif (V52xIPLx4-5LxΦx2YWxL72) is important for the suppression of both A3G and A3F (the FG box). To characterize the functional domains of Vif for A3H_HapII inactivation, we used a series of mutant Vif constructs that have been shown to be deficient in inactivating either A3G or A3F (9, 32, 97) (Fig. 3A). VifK22E and VifRH41/42AA are defective in suppressing A3G (G box mutants), whereas VifDR14/15AA (F1 box mutant) and VifW79A (F2 box mutant) are defective in suppressing A3F. The conserved motif V52xIPLx4-5LxΦx2YWxL72 mutants (Vif-P58A, L59S, L64S, I66S, Y69A, W70A, and L72S) are defective for both A3G and A3F inactivation.

FIG. 3.

Characterization of A3H_HapII interaction domains in Vif. (A) Diagram of the functional domains of Vif. (B) 293T cells were transfected with 1 μg of A3H_HapII and with empty vector or 3 μg of one of the Vif mutants VifDR14/15AA, VifK22E, VifRH41/42AA, or VifW79A. Cells were harvested at 48 h posttransfection and analyzed by SDS-PAGE, followed by immunoblotting, to detect A3H_HapII. (C) 293T cells were transfected with 1 μg of A3H_HapII and with empty vector or 3 μg of one of the Vif mutants VifP58A, VifL59S, VifL64S, VifI66S, VifY69A, VifW70A, or VifL72S. Cells were harvested at 48 h posttransfection and analyzed by SDS-PAGE, followed by immunoblotting, to detect A3H_HapII. (D) Coimmunoprecipitation analysis of wild-type Vif, VifDR14/15AA, VifRH41/42AA, or VifY69A with A3H_HapII. Three micrograms of A3H_HapII was cotransfected with 3 μg control plasmid or myc-tagged wild-type Vif, VifDR14/15AA, VifRH41/42AA, or VifY69A. At 36 h posttransfection, the cells were treated with MG132 for 16 h, and the cell lysates were harvested and immunoprecipitated with anti-myc antibody. Cell lysates and immunoprecipitates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE, followed by immunoblotting, to detect intracellular levels of the A3H_HapII and wild-type Vif and mutants and interactions between A3H_HapII and wild-type Vif and Vif mutants.

We first cotransfected 293T cells with A3H_HapII and with control vector or a plasmid expressing myc-tagged wild-type Vif, VifDR14/15AA, VifK22E, VifRH41/42AA, or VifW79A. VifK22E and Vif RH41/42AA, which are ineffective against A3G, also showed an impaired ability to reduce A3H_HapII protein levels compared to the wild-type Vif (Fig. 3B, compare lanes 4 and 5 to lane 2). VifK22E, which is uniquely defective for A3G suppression but not A3F, A3C, or A3DE suppression (9, 21), was also defective against A3H_HapII (data not shown). Interestingly, VifDR14/15AA also had an impaired ability to reduce A3H_HapII expression compared to the wild-type Vif (Fig. 3B, compare lanes 3 and 2). On the other hand, VifW79A could still efficiently reduce the A3H_HapII protein level (Fig. 3B, compare lanes 6 and 2).

Next, we asked whether the conserved motif V52xIPLx4-5LxΦx2YWxL72 of Vif was also important for A3H_HapII degradation. 293T cells were cotransfected with the A3H_HapII expression vector and VifP58A, VifL59S, VifL64S, VifI66S, VifY69A, VifW70A, VifL72S, or empty vector. As shown in Fig. 3C, many Vif mutants showed an impaired ability to reduce the expression of A3H_HapII compared to wild-type Vif, especially VifL64S, VifI66S, VifY69A, and VifL72S. These results are similar to those previously reported for A3G and A3F (32). We have found that HIV-1 Vif mutants that were defective for A3H_HapII inactivation also had a reduced ability to interact with A3H_HapII as indicated by the coimmunoprecipitation analysis (Fig. 3D). However, the combination of Vif motifs required for A3H_HapII suppression was different from that for A3G or A3F.

G105R is important for A3H protein stability and increased antiviral activity.

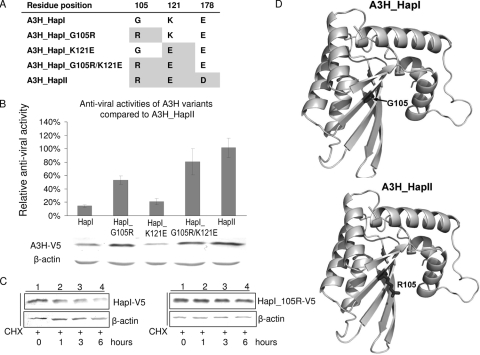

Since we had found significant differences in the antiviral activities and Vif sensitivities of A3H_HapI and A3H_HapII, we sought to identify the amino acid change(s) in A3H that is crucial for antiviral activity and Vif sensitivity. For this purpose, we used serial mutagenesis of A3H_HapI to develop the constructs A3H_HapI_G105R, A3H_HapI_K121E, and A3H_HapI_G105R/K121E (Fig. 4A).

FIG. 4.

Identification of amino acid changes that are crucial for the antiviral activity of APOBEC3H. (A) Schematic review of A3H constructs generated by site-directed mutagenesis. (B) Antiviral activity of A3H variants compared to A3H_HapII. HIV-1 viruses were produced in 293T cells cotransfected with 2 μg of NL4-3ΔVif and with 2 μg of empty vector or of A3H_HapI, A3H_HapI_G105R, A3H_HapI_K121E, A3H_HapI_G105R/121E, or A3H_HapII. Viral infectivity was assessed by MAGI assay, with viral infectivity in the presence of A3H_HapII set to 100%. Error bars represent the standard deviations from triplicate wells. Cell lysates were harvested at 48 h posttransfection and analyzed by SDS-PAGE, followed by immunoblotting, to detect A3H variants. (C) Cycloheximide (CHX) chase analysis of A3H_HapI and A3H _105R. 293T cells were transfected with 200 ng A3H_HapI or 200 ng A3H_G105R. At 48 h posttransfection, cells were treated with 100 μg/ml CHX (Sigma) and harvested at 0, 1, 3, and 6 h. The cell lysate were analyzed by SDS-PAGE, followed by immunoblotting with anti-V5 antibody, to determine intracellular levels of A3H_HapI and A3H_G105R. (D) Protein structure model for A3H_HapI and HapI_105R, based on homology modeling of the crystal structure of APOBEC2 and the nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) structure of the C-terminal domain of A3G.

To look for changes in the antiviral activity of these A3H variants, we cotransfected 293T cells with NL4-3ΔVif, together with empty vector or one of the A3H expression plasmids, and then tested the infectivity of virus produced using MAGI assays (Fig. 4B). A3H_HapII showed the highest level of antiviral activity (set to 100%) compared to HapI (14.6%). In particular, a single amino acid change from 105G to R in HapI significantly increased its antiviral activity (from 14.6% to 53.34%), with HapI_G105R/K121E exhibiting an antiviral activity (80.79%) that was almost the same as that of HapII. However, a single amino acid change from 121K to E did not significantly improve the antiviral activity of A3H_HapI (20.76%). We also examined the protein levels of these A3H constructs. As expected, HapI_G105R and HapI_G105R/K121E showed an increased level of protein expression compared to that of A3H_HapI, whereas protein expression of HapI_K121E remained comparable to that of A3H_HapI (Fig. 4B). Cycloheximide chase analysis indicated that HapI_G105R was indeed more stable than HapI (Fig. 4C).

The increase in the stability of A3H_HapI that we observed at the protein level after a single mutation of G105R is somewhat intriguing, since our homology modeling of the amino-terminal domain of A3G using the crystal structures of both APOBEC2 and the carboxyl-terminal domain of A3G had predicted that this residue would be exposed on the surface and have no effect on protein folding (Fig. 4D). The possibility still remains that this residue is involved in interactions with as-yet-unidentified cellular partners that regulate the stability of A3H. Alternatively, the fact that the G105R mutation adds a positive charge on the surface of the protein and reduces its hydrophobicity suggests that this mutation could possibly confer an increased stability on the protein when in aqueous solution.

Amino acid K121 is critical for the resistance of A3H_HapI to Vif.

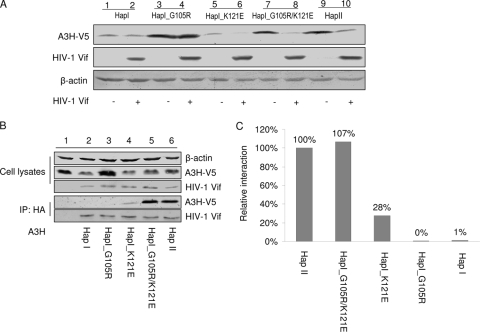

We next asked which amino acid residue(s) of A3H might be crucial for its sensitivity to Vif-mediated degradation. To answer this question, we cotransfected the expression vector for A3H_HapI, A3H_HapI_G105R, A3H_HapI_K121E, A3H_HapI_G105R/K121E, or A3H_HapII with wild-type Vif or a control empty vector into 293T cells. Cell lysates were harvested at 48 h posttransfection and subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting. As shown in Fig. 5A, a single amino acid substitution at position 105 from G to R, although greatly increasing the level of protein expression, had no effect on the sensitivity of the A3H_HapI mutant to HIV-1 Vif (Fig. 5A, lanes 3 and 4). In contrast, a single amino acid substitution at position 121, from K to E, was sufficient to render A3H_HapI_K121E Vif sensitive (Fig. 5A, lanes 5 and 6). When both amino acids at position 105 and 121 were substituted to match the sequence of Vif-sensitive A3H_HapII, the Vif-mediated degradation of the resulting A3H_HapI_G105R/K121E (Fig. 5A, lanes 7 and 8) was equivalent to that of A3H_HapII (Fig. 5A, lanes 9 and 10).

FIG. 5.

Identification of amino acids that are crucial for Vif-mediated degradation and Vif binding. (A) 293T cells were cotransfected with 1 μg of A3H variant and with 3 μg of empty vector or Vif-myc expression plasmid. At 48 h posttransfection, the cells were harvested and analyzed by SDS-PAGE, followed by immunoblotting, to detect A3H variants. (B) 293T cells were cotransfected with 2 μg of A3H variant and 2 μg of Vif-HA expression plasmid or empty vector. At 36 h posttransfection, the cells were treated with MG132 for 16 h, and the cell lysates were harvested and immunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibody. Cell lysates and immunoprecipitates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE, followed by immunoblotting, to detect intracellular levels of the A3H variants and interactions between Vif and the A3H variants. (C) The bar graph shows the relative interactions of the A3H variants with Vif. The intensities of the immunoblot bands of the A3H variants after immunoprecipitation were quantified using ImageJ software and normalized to that of A3H_HapII.

We then investigated whether an interaction between A3H_HapII and HIV-1 Vif takes place and, if so, which amino acid(s) might be involved in this interaction. Plasmids expressing HA-tagged Vif and each of the A3H variants described in Fig. 4A were cotransfected into 293T cells. At 36 h posttransfection, cells were treated with MG132 for 16 h, and immunoprecipitation was performed using an anti-HA affinity matrix (Roche). Cell lysates and immunoprecipitated samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting. We were able to detect coprecipitation of A3H_HapII with HIV-1 Vif (Fig. 5B, lane 6) and determined that this interaction was specific because A3H_HapII was not detected in the absence of Vif (Fig. 5B, lane 1). The relative intensities of the bands produced by the various A3H constructs after immunoprecipitation were determined by normalization to A3H_HapII (set to 100%). In these experiments, A3H_HapI and HapI_G105R, which were resistant to Vif-mediated degradation, also demonstrated little Vif binding activity (Fig. 5B and C). In contrast, HapI_K121E and HapI_G105R/K121E coimmunoprecipitated with Vif, indicating that position 121 of A3H is critical for Vif binding (Fig. 5B). Thus, the difference in Vif sensitivity among A3H variants was directly correlated to their differential recognition by Vif.

DISCUSSION

Four haplotypes of A3H with distinct antiretroviral and antiretroelement activities have been identified in human populations (19, 29, 59, 60, 79). However, recent findings about antiviral activity and Vif sensitivity of A3H variants are conflicting (19, 29, 58, 79). While some groups argued that A3H_HapI is poorly expressed when transfected into mammalian cells and contains weak antiviral activity (59, 79), other groups reported that A3H_HapI is a strong HIV-1 inhibitor (19, 29). Notably, the latter groups used expression vector VR1012 or pTR600, which contain intron A to achieve high level of A3H_HapI expression. In this study, we showed that when A3H_HapI expression was increased to level similar to that of A3H_HapII, its anti-HIV-1 activity was also comparable to that of A3H_HapII. Therefore, it appears that antiviral activity of A3H is, at least in the case of HapI and HapII, directly correlated to the level of protein expression. In agreement with others, (29, 59), we found that position 105 of A3H was crucial in determining protein stability (Fig. 4C).

Whether A3H variants are suppressed by HIV-1 Vif has also been a controversial issue (19, 29, 58). In the present study, we have demonstrated that A3H_HapI is resistant to HIV-1 Vif, which is consistent with all the other reports (19, 29, 58). However, we found that A3H_HapII can be inactivated by HIV-1 Vif, which is consistent with a report from OhAinle and colleagues (58). HIV-1 Vif induced degradation of A3H_HapII, which could be blocked by the proteasome inhibitor MG132, indicating the involvement of the ubiquitin-proteasome system in the degradation of these proteins. Inactivation of A3H_HapII by HIV-1 Vif was also dependent on the ability of Vif to assemble with the host Cul5-ElonginB-ElonginC E3 ubiquitin ligase. It has been reported that A3H_HapII may be resistant to HIV-1 Vif (29). In that study, a higher level of A3H_HapII expression was achieved using an expression vector that contains intron A (29). In fact, the ability of HIV-1 Vif to inactivate A3G could also be compromised when A3G overexpression was achieved (48).

Interestingly, A3H_HapI, differing in only three amino acids from A3H_HapII, is resistant to Vif-mediated degradation but is less active than A3H_HapII against HIV-1. To identify the amino acids that are crucial for this variation in Vif sensitivity, we generated multiple A3H constructs and compared the antiviral activities and Vif sensitivities of these mutant constructs, i.e., A3H_HapI, A3H_HapI_G105R, A3H_HapI_K121E, A3H_HapI_G105R/K121E, and A3H_HapII. Consistent with the findings of other groups (29, 58), we determined that a single amino acid change at position 105 from G to R significantly increased the expression level of A3H_HapI in the transfected 293T cells. A3H_HapI_G105R also had significantly increased anti-HIV-1 activity but remained resistant to Vif-mediated degradation. In contrast, while a single amino acid change at position121 from K to E did not improve A3H_HapI protein expression or anti-HIV-1 activity, A3H_HapI_K121E became sensitive to Vif-mediated degradation. We also showed that this single amino change increased the interaction of A3H with HIV-1 Vif. Therefore, the difference in Vif sensitivity was correlated with the ability of A3H variants to interact with HIV-1 Vif protein. Thus, for the first time, we were able to demonstrate that position 121 of A3H is a critical determinant of Vif-mediated interaction and inactivation.

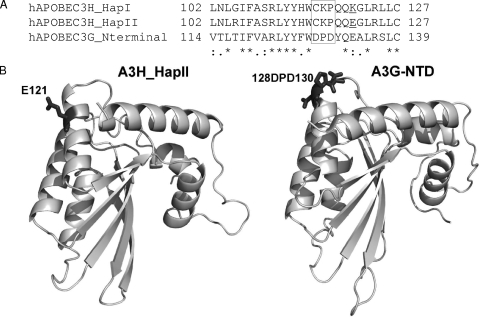

A single amino acid (position 128) in human A3G can determine HIV-1 Vif sensitivity (6, 34, 47, 48, 65, 67, 86). More recently, a DPD motif (amino acids 128 to 130) in A3G has been shown to be critical for Vif recognition and inactivation (34, 65). Alignment of the amino-terminal domains of human A3G, A3H_HapI, and A3H_HapII indicated the absence of the DPD motif in human A3H molecules (Fig. 6A). This finding suggests that Vif may interact with distinct protein motifs on A3H_HapII and A3G.

FIG. 6.

Sequence alignment and model structure comparisons between the amino-terminal domains of A3H_HapI, A3H_HapII, and A3G. (A) Amino acid sequence alignment (positions 102 to 127) of the A3H_HapI, HapII, and A3G amino-terminal domains. The DPD motif in A3G is marked by a box. (B) A3H_HapII and A3G N-terminal protein structure models based on homology modeling as described in Materials and Methods. Amino acids 128D to 130D of A3G and 121E of A3H_HapII are marked.

Our homology modeling of the amino-terminal domains of A3G and A3H_HapII showed that amino acid 121E appears to be localized on the surface of A3H_HapII, slightly downstream from the positions of the DPD residues in A3G (Fig. 6B). It is interesting to note that in both A3H_HapII and A3G, negatively charged residues are important for Vif recognition and inactivation, suggesting that electrostatic interactions play a critical role in the interaction between Vif and certain APOBEC3 proteins.

Consistent with this idea, a region rich in positively charged amino acids in HIV-1 Vif was found to be critical for A3H_HapII inactivation (Fig. 3). Since these positively charged residues in HIV-1 Vif were shown to be important for A3G inactivation (9, 21) but dispensable for A3F, A3C, and A3DE inactivation, one could argue that HIV-1 Vif recognizes A3H_HapII and A3G through similar mechanisms. Indeed, we found that a conserved hydrophobic motif, 52VxIPLx4-5LxΦx2YWxL72, in Vif that is important for both A3G and A3F inactivation was also important for A3H_HapII suppression. Surprisingly, we also observed that a motif (the F1 box) in HIV-1 Vif that is required for A3F but not A3G inactivation was also important for A3H_HapII inactivation. Thus, HIV-1 Vif has evolved to use different combinations of functional motifs to inactivate A3G, A3F, and A3H_HapII (Fig. 3D). Only the hydrophobic 52VxIPLx4-5LxΦx2YWxL72 motif is required for the inactivation of all APOBEC3 proteins.

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Evan, A. Niewiadomska, and W. Zhang for advice and technical assistance; Yonghui Zheng (Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI), M. Ooms, and V. Simon (Department of Medicine and Microbiology, Emerging Pathogens Institute, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, NY) for sharing reagents, helpful discussions, and advice; and D. McClellan for editorial assistance. MAGI-CCR5 cells and the NL4-3 and NL4-3ΔVif constructs were obtained through the AIDS Research and Reference Reagents Program, Division of AIDS, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH.

This work was supported by grants from the NIH (AI062644 and AI071769) to X.F.Y.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 25 November 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Battey, J. N., J. Kopp, L. Bordoli, R. J. Read, N. D. Clarke, and T. Schwede. 2007. Automated server predictions in CASP7. Proteins 69(Suppl. 8):68-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bieniasz, P. D. 2004. Intrinsic immunity: a front-line defense against viral attack. Nat. Immunol. 5:1109-1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bishop, K. N., R. K. Holmes, and M. H. Malim. 2006. Antiviral potency of APOBEC proteins does not correlate with cytidine deamination. J. Virol. 80:8450-8458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bishop, K. N., R. K. Holmes, A. M. Sheehy, N. O. Davidson, S. J. Cho, and M. H. Malim. 2004. Cytidine deamination of retroviral DNA by diverse APOBEC proteins. Curr. Biol. 14:1392-1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bishop, K. N., M. Verma, E. Y. Kim, S. M. Wolinsky, and M. H. Malim. 2008. APOBEC3G inhibits elongation of HIV-1 reverse transcripts. PLoS Pathog. 4:e1000231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bogerd, H. P., B. P. Doehle, H. L. Wiegand, and B. R. Cullen. 2004. A single amino acid difference in the host APOBEC3G protein controls the primate species specificity of HIV type 1 virion infectivity factor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:3770-3774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bogerd, H. P., H. L. Wiegand, B. P. Doehle, K. K. Lueders, and B. R. Cullen. 2006. APOBEC3A and APOBEC3B are potent inhibitors of LTR-retrotransposon function in human cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 34:89-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bogerd, H. P., H. L. Wiegand, A. E. Hulme, J. L. Garcia-Perez, K. S. O'Shea, J. V. Moran, and B. R. Cullen. 2006. Cellular inhibitors of long interspersed element 1 and Alu retrotransposition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:8780-8785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen, G., Z. He, T. Wang, R. Xu, and X. F. Yu. 2009. A patch of positively charged amino acids surrounding the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vif SLVx4Yx9Y motif influences its interaction with APOBEC3G. J. Virol. 83:8674-8682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen, H., C. E. Lilley, Q. Yu, D. V. Lee, J. Chou, I. Narvaiza, N. R. Landau, and M. D. Weitzman. 2006. APOBEC3A is a potent inhibitor of adeno-associated virus and retrotransposons. Curr. Biol. 16:480-485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen, K. M., E. Harjes, P. J. Gross, A. Fahmy, Y. Lu, K. Shindo, R. S. Harris, and H. Matsuo. 2008. Structure of the DNA deaminase domain of the HIV-1 restriction factor APOBEC3G. Nature 452:116-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chiu, Y. L., and W. C. Greene. 2008. The APOBEC3 cytidine deaminases: an innate defensive network opposing exogenous retroviruses and endogenous retroelements. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 26:317-353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chiu, Y. L., and W. C. Greene. 2006. APOBEC3 cytidine deaminases: distinct antiviral actions along the retroviral life cycle. J. Biol. Chem. 281:8309-8312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chiu, Y. L., H. E. Witkowska, S. C. Hall, M. Santiago, V. B. Soros, C. Esnault, T. Heidmann, and W. C. Greene. 2006. High-molecular-mass APOBEC3G complexes restrict Alu retrotransposition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:15588-15593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Conticello, S. G. 2008. The AID/APOBEC family of nucleic acid mutators. Genome Biol. 9:229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Conticello, S. G., R. S. Harris, and M. S. Neuberger. 2003. The Vif protein of HIV triggers degradation of the human antiretroviral DNA deaminase APOBEC3G. Curr. Biol. 13:2009-2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Conticello, S. G., C. J. Thomas, S. K. Petersen-Mahrt, and M. S. Neuberger. 2005. Evolution of the AID/APOBEC family of polynucleotide (deoxy)cytidine deaminases. Mol. Biol. Evol. 22:367-377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cullen, B. R. 2006. Role and mechanism of action of the APOBEC3 family of antiretroviral resistance factors. J. Virol. 80:1067-1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dang, Y., L. M. Siew, X. Wang, Y. Han, R. Lampen, and Y. H. Zheng. 2008. Human cytidine deaminase APOBEC3H restricts HIV-1 replication. J. Biol. Chem. 283:11606-11614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dang, Y., X. Wang, W. J. Esselman, and Y. H. Zheng. 2006. Identification of APOBEC3DE as another antiretroviral factor from the human APOBEC family. J. Virol. 80:10522-10533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dang, Y., X. Wang, T. Zhou, I. A. York, and Y. H. Zheng. 2009. Identification of a novel WxSLVK motif in the N terminus of human immunodeficiency virus and simian immunodeficiency virus Vif that is critical for APOBEC3G and APOBEC3F neutralization. J. Virol. 83:8544-8552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Doehle, B. P., A. Schafer, and B. R. Cullen. 2005. Human APOBEC3B is a potent inhibitor of HIV-1 infectivity and is resistant to HIV-1 Vif. Virology 339:281-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Doehle, B. P., A. Schafer, H. L. Wiegand, H. P. Bogerd, and B. R. Cullen. 2005. Differential sensitivity of murine leukemia virus to APOBEC3-mediated inhibition is governed by virion exclusion. J. Virol. 79:8201-8207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Edgar, R. C. 2004. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:1792-1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Esnault, C., O. Heidmann, F. Delebecque, M. Dewannieux, D. Ribet, A. J. Hance, T. Heidmann, and O. Schwartz. 2005. APOBEC3G cytidine deaminase inhibits retrotransposition of endogenous retroviruses. Nature 433:430-433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goff, S. P. 2004. Retrovirus restriction factors. Mol. Cell 16:849-859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goila-Gaur, R., and K. Strebel. 2008. HIV-1 Vif, APOBEC, and intrinsic immunity. Retrovirology 5:51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guo, F., S. Cen, M. Niu, J. Saadatmand, and L. Kleiman. 2006. Inhibition of formula-primed reverse transcription by human APOBEC3G during human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication. J. Virol. 80:11710-11722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harari, A., M. Ooms, L. C. Mulder, and V. Simon. 2009. Polymorphisms and splice variants influence the antiretroviral activity of human APOBEC3H. J. Virol. 83:295-303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harris, R. S., K. N. Bishop, A. M. Sheehy, H. M. Craig, S. K. Petersen-Mahrt, I. N. Watt, M. S. Neuberger, and M. H. Malim. 2003. DNA deamination mediates innate immunity to retroviral infection. Cell 113:803-809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harris, R. S., and M. T. Liddament. 2004. Retroviral restriction by APOBEC proteins. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 4:868-877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.He, Z., W. Zhang, G. Chen, R. Xu, and X. F. Yu. 2008. Characterization of conserved motifs in HIV-1 Vif required for APOBEC3G and APOBEC3F interaction. J. Mol. Biol. 381:1000-1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Holden, L. G., C. Prochnow, Y. P. Chang, R. Bransteitter, L. Chelico, U. Sen, R. C. Stevens, M. F. Goodman, and X. S. Chen. 2008. Crystal structure of the anti-viral APOBEC3G catalytic domain and functional implications. Nature 456:121-124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huthoff, H., and M. H. Malim. 2007. Identification of amino acid residues in APOBEC3G required for regulation by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vif and virion encapsidation. J. Virol. 81:3807-3815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaiser, S. M., and M. Emerman. 2006. Uracil DNA glycosylase is dispensable for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication and does not contribute to the antiviral effects of the cytidine deaminase Apobec3G. J. Virol. 80:875-882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kao, S., M. A. Khan, E. Miyagi, R. Plishka, A. Buckler-White, and K. Strebel. 2003. The human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vif protein reduces intracellular expression and inhibits packaging of APOBEC3G (CEM15), a cellular inhibitor of virus infectivity. J. Virol. 77:11398-11407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kobayashi, M., A. Takaori-Kondo, K. Shindo, A. Abudu, K. Fukunaga, and T. Uchiyama. 2004. APOBEC3G targets specific virus species. J. Virol. 78:8238-8244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kremer, M., A. Bittner, and B. S. Schnierle. 2005. Human APOBEC3G incorporation into murine leukemia virus particles. Virology 337:175-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Langlois, M. A., R. C. Beale, S. G. Conticello, and M. S. Neuberger. 2005. Mutational comparison of the single-domained APOBEC3C and double-domained APOBEC3F/G anti-retroviral cytidine deaminases provides insight into their DNA target site specificities. Nucleic Acids Res. 33:1913-1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lecossier, D., F. Bouchonnet, F. Clavel, and A. J. Hance. 2003. Hypermutation of HIV-1 DNA in the absence of the Vif protein. Science 300:1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liddament, M. T., W. L. Brown, A. J. Schumacher, and R. S. Harris. 2004. APOBEC3F properties and hypermutation preferences indicate activity against HIV-1 in vivo. Curr. Biol. 14:1385-1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu, B., X. Yu, K. Luo, Y. Yu, and X. F. Yu. 2004. Influence of primate lentiviral Vif and proteasome inhibitors on human immunodeficiency virus type 1 virion packaging of APOBEC3G. J. Virol. 78:2072-2081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Luo, K., T. Wang, B. Liu, C. Tian, Z. Xiao, J. Kappes, and X. F. Yu. 2007. Cytidine deaminases APOBEC3G and APOBEC3F interact with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase and inhibit proviral DNA formation. J. Virol. 81:7238-7248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Luo, K., Z. Xiao, E. Ehrlich, Y. Yu, B. Liu, S. Zheng, and X. F. Yu. 2005. Primate lentiviral virion infectivity factors are substrate receptors that assemble with cullin 5-E3 ligase through a HCCH motif to suppress APOBEC3G. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:11444-11449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Malim, M. H., and M. Emerman. 2008. HIV-1 accessory proteins—ensuring viral survival in a hostile environment. Cell Host Microbe 3:388-398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mangeat, B., P. Turelli, G. Caron, M. Friedli, L. Perrin, and D. Trono. 2003. Broad antiretroviral defence by human APOBEC3G through lethal editing of nascent reverse transcripts. Nature 424:99-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mangeat, B., P. Turelli, S. Liao, and D. Trono. 2004. A single amino acid determinant governs the species-specific sensitivity of APOBEC3G to Vif action. J. Biol. Chem. 279:14481-14483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mariani, R., D. Chen, B. Schrofelbauer, F. Navarro, R. Konig, B. Bollman, C. Munk, H. Nymark-McMahon, and N. R. Landau. 2003. Species-specific exclusion of APOBEC3G from HIV-1 virions by Vif. Cell 114:21-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Marin, M., K. M. Rose, S. L. Kozak, and D. Kabat. 2003. HIV-1 Vif protein binds the editing enzyme APOBEC3G and induces its degradation. Nat. Med. 9:1398-1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mbisa, J. L., R. Barr, J. A. Thomas, N. Vandegraaff, I. J. Dorweiler, E. S. Svarovskaia, W. L. Brown, L. M. Mansky, R. J. Gorelick, R. S. Harris, A. Engelman, and V. K. Pathak. 2007. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 cDNAs produced in the presence of APOBEC3G exhibit defects in plus-strand DNA transfer and integration. J. Virol. 81:7099-7110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mehle, A., J. Goncalves, M. Santa-Marta, M. McPike, and D. Gabuzda. 2004. Phosphorylation of a novel SOCS-box regulates assembly of the HIV-1 Vif-Cul5 complex that promotes APOBEC3G degradation. Genes Dev. 18:2861-2866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mehle, A., E. R. Thomas, K. S. Rajendran, and D. Gabuzda. 2006. A zinc-binding region in Vif binds Cul5 and determines cullin selection. J. Biol. Chem. 281:17259-17265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mehle, A., H. Wilson, C. Zhang, A. J. Brazier, M. McPike, E. Pery, and D. Gabuzda. 2007. Identification of an APOBEC3G binding site in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vif and inhibitors of Vif-APOBEC3G binding. J. Virol. 81:13235-13241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Miyagi, E., S. Opi, H. Takeuchi, M. Khan, R. Goila-Gaur, S. Kao, and K. Strebel. 2007. Enzymatically active APOBEC3G is required for efficient inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 81:13346-13353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Muckenfuss, H., M. Hamdorf, U. Held, M. Perkovic, J. Lower, K. Cichutek, E. Flory, G. G. Schumann, and C. Munk. 2006. APOBEC3 proteins inhibit human LINE-1 retrotransposition. J. Biol. Chem. 281:22161-22172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Newman, E. N., R. K. Holmes, H. M. Craig, K. C. Klein, J. R. Lingappa, M. H. Malim, and A. M. Sheehy. 2005. Antiviral function of APOBEC3G can be dissociated from cytidine deaminase activity. Curr. Biol. 15:166-170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Noguchi, C., H. Ishino, M. Tsuge, Y. Fujimoto, M. Imamura, S. Takahashi, and K. Chayama. 2005. G to A hypermutation of hepatitis B virus. Hepatology 41:626-633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.OhAinle, M., J. A. Kerns, M. M. Li, H. S. Malik, and M. Emerman. 2008. Antiretroelement activity of APOBEC3H was lost twice in recent human evolution. Cell Host Microbe 4:249-259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.OhAinle, M., J. A. Kerns, H. S. Malik, and M. Emerman. 2006. Adaptive evolution and antiviral activity of the conserved mammalian cytidine deaminase APOBEC3H. J. Virol. 80:3853-3862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Opi, S., S. Kao, R. Goila-Gaur, M. A. Khan, E. Miyagi, H. Takeuchi, and K. Strebel. 2007. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vif inhibits packaging and antiviral activity of a degradation-resistant APOBEC3G variant. J. Virol. 81:8236-8246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pery, E., K. S. Rajendran, A. J. Brazier, and D. Gabuzda. 2009. Regulation of APOBEC3 proteins by a novel YXXL motif in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vif and simian immunodeficiency virus SIVagm Vif. J. Virol. 83:2374-2381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Prochnow, C., R. Bransteitter, M. G. Klein, M. F. Goodman, and X. S. Chen. 2007. The APOBEC-2 crystal structure and functional implications for the deaminase AID. Nature 445:447-451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rosler, C., J. Kock, M. H. Malim, H. E. Blum, and F. von Weizsacker. 2004. Comment on “Inhibition of hepatitis B virus replication by APOBEC3G.” Science 305:1403. (Author reply, 305:1403.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Russell, R. A., and V. K. Pathak. 2007. Identification of two distinct human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vif determinants critical for interactions with human APOBEC3G and APOBEC3F. J. Virol. 81:8201-8210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Russell, R. A., J. Smith, R. Barr, D. Bhattacharyya, and V. K. Pathak. 2009. Distinct domains within APOBEC3G and APOBEC3F interact with separate regions of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vif. J. Virol. 83:1992-2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sali, A., and T. L. Blundell. 1993. Comparative protein modelling by satisfaction of spatial restraints. J. Mol. Biol. 234:779-815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schrofelbauer, B., D. Chen, and N. R. Landau. 2004. A single amino acid of APOBEC3G controls its species-specific interaction with virion infectivity factor (Vif). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:3927-3932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Schrofelbauer, B., T. Senger, G. Manning, and N. R. Landau. 2006. Mutational alteration of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vif allows for functional interaction with nonhuman primate APOBEC3G. J. Virol. 80:5984-5991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Schrofelbauer, B., Q. Yu, S. G. Zeitlin, and N. R. Landau. 2005. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpr induces the degradation of the UNG and SMUG uracil-DNA glycosylases. J. Virol. 79:10978-10987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Schumacher, A. J., G. Hache, D. A. Macduff, W. L. Brown, and R. S. Harris. 2008. The DNA deaminase activity of human APOBEC3G is required for Ty1, MusD, and human immunodeficiency virus type 1 restriction. J. Virol. 82:2652-2660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schumacher, A. J., D. V. Nissley, and R. S. Harris. 2005. APOBEC3G hypermutates genomic DNA and inhibits Ty1 retrotransposition in yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:9854-9859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sheehy, A. M., N. C. Gaddis, J. D. Choi, and M. H. Malim. 2002. Isolation of a human gene that inhibits HIV-1 infection and is suppressed by the viral Vif protein. Nature 418:646-650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sheehy, A. M., N. C. Gaddis, and M. H. Malim. 2003. The antiretroviral enzyme APOBEC3G is degraded by the proteasome in response to HIV-1 Vif. Nat. Med. 9:1404-1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Simon, V., V. Zennou, D. Murray, Y. Huang, D. D. Ho, and P. D. Bieniasz. 2005. Natural variation in Vif: differential impact on APOBEC3G/3F and a potential role in HIV-1 diversification. PLoS Pathog. 1:e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Stenglein, M. D., and R. S. Harris. 2006. APOBEC3B and APOBEC3F inhibit L1 retrotransposition by a DNA deamination-independent mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 281:16837-16841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Stopak, K., C. de Noronha, W. Yonemoto, and W. C. Greene. 2003. HIV-1 Vif blocks the antiviral activity of APOBEC3G by impairing both its translation and intracellular stability. Mol. Cell 12:591-601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Suspene, R., D. Guetard, M. Henry, P. Sommer, S. Wain-Hobson, and J. P. Vartanian. 2005. Extensive editing of both hepatitis B virus DNA strands by APOBEC3 cytidine deaminases in vitro and in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:8321-8326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Suspene, R., P. Sommer, M. Henry, S. Ferris, D. Guetard, S. Pochet, A. Chester, N. Navaratnam, S. Wain-Hobson, and J. P. Vartanian. 2004. APOBEC3G is a single-stranded DNA cytidine deaminase and functions independently of HIV reverse transcriptase. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:2421-2429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tan, L., P. T. Sarkis, T. Wang, C. Tian, and X. F. Yu. 2008. Sole copy of Z2-type human cytidine deaminase APOBEC3H has inhibitory activity against retrotransposons and HIV-1. FASEB J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 80.Tian, C., X. Yu, W. Zhang, T. Wang, R. Xu, and X. F. Yu. 2006. Differential requirement for conserved tryptophans in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vif for the selective suppression of APOBEC3G and APOBEC3F. J. Virol. 80:3112-3115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Turelli, P., B. Mangeat, S. Jost, S. Vianin, and D. Trono. 2004. Inhibition of hepatitis B virus replication by APOBEC3G. Science 303:1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Turelli, P., and D. Trono. 2005. Editing at the crossroad of innate and adaptive immunity. Science 307:1061-1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Xiao, Z., E. Ehrlich, K. Luo, Y. Xiong, and X. F. Yu. 2007. Zinc chelation inhibits HIV Vif activity and liberates antiviral function of the cytidine deaminase APOBEC3G. FASEB J. 21:217-222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Xiao, Z., E. Ehrlich, Y. Yu, K. Luo, T. Wang, C. Tian, and X. F. Yu. 2006. Assembly of HIV-1 Vif-Cul5 E3 ubiquitin ligase through a novel zinc-binding domain-stabilized hydrophobic interface in Vif. Virology 349:290-299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Xiao, Z., Y. Xiong, W. Zhang, L. Tan, E. Ehrlich, D. Guo, and X. F. Yu. 2007. Characterization of a novel cullin5 binding domain in HIV-1 Vif. J. Mol. Biol. 373:541-550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Xu, H., E. S. Svarovskaia, R. Barr, Y. Zhang, M. A. Khan, K. Strebel, and V. K. Pathak. 2004. A single amino acid substitution in human APOBEC3G antiretroviral enzyme confers resistance to HIV-1 virion infectivity factor-induced depletion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:5652-5657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Yamashita, T., K. Kamada, K. Hatcho, A. Adachi, and M. Nomaguchi. 2008. Identification of amino acid residues in HIV-1 Vif critical for binding and exclusion of APOBEC3G/F. Microbes Infect. 10:1142-1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Yang, Y., F. Guo, S. Cen, and L. Kleiman. 2007. Inhibition of initiation of reverse transcription in HIV-1 by human APOBEC3F. Virology 365:92-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Yu, Q., D. Chen, R. Konig, R. Mariani, D. Unutmaz, and N. R. Landau. 2004. APOBEC3B and APOBEC3C are potent inhibitors of simian immunodeficiency virus replication. J. Biol. Chem. 279:53379-53386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Yu, Q., R. Konig, S. Pillai, K. Chiles, M. Kearney, S. Palmer, D. Richman, J. M. Coffin, and N. R. Landau. 2004. Single-strand specificity of APOBEC3G accounts for minus-strand deamination of the HIV genome. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 11:435-442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Yu, X. 2006. Innate cellular defenses of APOBEC3 cytidine deaminases and viral counter-defenses. Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS 1:187-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Yu, X., Y. Yu, B. Liu, K. Luo, W. Kong, P. Mao, and X. F. Yu. 2003. Induction of APOBEC3G ubiquitination and degradation by an HIV-1 Vif-Cul5-SCF complex. Science 302:1056-1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Yu, Y., Z. Xiao, E. S. Ehrlich, X. Yu, and X. F. Yu. 2004. Selective assembly of HIV-1 Vif-Cul5-ElonginB-ElonginC E3 ubiquitin ligase complex through a novel SOCS box and upstream cysteines. Genes Dev. 18:2867-2872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Zhang, H., B. Yang, R. J. Pomerantz, C. Zhang, S. C. Arunachalam, and L. Gao. 2003. The cytidine deaminase CEM15 induces hypermutation in newly synthesized HIV-1 DNA. Nature 424:94-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Zhang, H. Y., L. Jin, G. A. Stilling, K. H. Ruebel, K. Coonse, Y. Tanizaki, A. Raz, and R. V. Lloyd. 2009. RUNX1 and RUNX2 upregulate Galectin-3 expression in human pituitary tumors. Endocrine 35:101-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Zhang, W., G. Chen, A. M. Niewiadomska, R. Xu, and X. F. Yu. 2008. Distinct determinants in HIV-1 Vif and human APOBEC3 proteins are required for the suppression of diverse host anti-viral proteins. PLoS One 3:e3963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Zhang, W., M. Huang, T. Wang, L. Tan, C. Tian, X. Yu, W. Kong, and X. F. Yu. 2008. Conserved and non-conserved features of HIV-1 and SIVagm Vif mediated suppression of APOBEC3 cytidine deaminases. Cell. Microbiol. 10:1662-1675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Zheng, Y. H., D. Irwin, T. Kurosu, K. Tokunaga, T. Sata, and B. M. Peterlin. 2004. Human APOBEC3F is another host factor that blocks human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication. J. Virol. 78:6073-6076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]