Abstract

Strongyloides stercoralis is a unique parasite. It can complete its life cycle entirely within the human host. As a result, an autoinfection cycle is set up. As long as there is an intact immune system, the host can control the parasitic burden, and the organism may persist for years after the initial inoculum. Most infected individuals experience mild gastrointestinal or pulmonary symptoms that may fluctuate for years. When cell-mediated immunity becomes impaired (ie, corticosteroid use, malignancy, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome), the parasite burden will grow, disseminate, and cause hyperinfection. Strongyloidiasis is endemic in the tropical and subtropical areas of the world; additionally, it is also endemic in the southeastern United States. Strongyloidiasis is associated with asthma, preexisting lung disease, and immunosuppression, including acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Eosinophilia is not a prerequisite; therefore, the diagnosis of strongyloidiasis requires a high index of suspicion.

Keywords: Strongyloides stercoralis, strongyloidiasis, autoinfection, hyperinfection, eosinophilia

CASE 1

A 37-year-old Guatemalan woman with history of advanced human immunodeficiency syndrome/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) was hospitalized with a 3-month history of progressive dyspnea, dry cough, epigastric abdominal pain, diarrhea, and weight loss. Her past medical history included 2 prior episodes of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP) and an ill-defined interstitial lung disease. Her most recent CD4 count was 17 cells/mm3 with viral load of more than 100,000 copies. She was not taking any medications, denied any smoking history and illicit drug use, and had been living in United States for the past 20 years.

On physical examination, she was tachypneic and febrile. Pertinent physical findings included dry bibasilar end-inspiratory crackles and moderate right upper quadrant and epigastric tenderness. Laboratory data included hemoglobin of 6.4 g/dL and total leukocyte count of 6000/mL without eosinophilia. Serum lipase and lactate dehydrogenase levels were elevated at 270 IU/dL and 296 IU/dL, respectively, with normal levels of hepatic transaminases, alkaline phosphatase, and total bilirubin. Arterial blood gases on room air revealed pH of 7.45, PCO2 of 30 mm Hg, PO2 of 49 mm Hg, and HCO3 of 22 mEq/L. Chest radiograph demonstrated diffuse bilateral interstitial infiltrates. Blood and urine cultures remained negative.

She was treated for presumptive PCP with trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole and prednisone. Abdominal ultrasound revealed dilated common bile duct of 10 mm. Endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography (ERCP) revealed common bile duct dilatation with smooth distal narrowing and no evidence of gallstones. On the sixth hospital day, she developed severe hypoxemia requiring endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation. A diagnostic fiberoptic bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage revealed numerous Strongyloides stercoralis larvae and was negative for P. carinii (Fig. 1). S. stercoralis was also isolated from the biliary secretions obtained during ERCP. Despite 2 courses of oral ivermectin, she developed sepsis-induced multiple organ dysfunction and expired a few weeks later.

FIGURE 1.

Photomicrograph of Strongyloides stercoralis filariform larva recovered from the bronchoalveolar lavage in case 1 (Diff-Quick stain, original magnification ×100)

This case illustrates several key points: (1) immunosuppresion induced by corticosteroids can lead to hyperinfection syndrome; (2) even a remote history of travel or prior residence in an endemic area may be significant; and (3) disseminated strongyloidiasis can present with chronic history of nonspecific respiratory and gastrointestinal symptoms in immunocompromised patients.

CASE 2

A 67-year-old hypertensive man from Puerto Rico was referred to the pulmonary clinic because of frequent exacerbations of asthma. He had been diagnosed with asthma 1 year prior to referral. In spite of using fluticasone metered-dose inhaler (MDI; 220 µg/puff, 2 puffs twice a day) and albuterol MDI, he had 6 visits to the emergency room over a 1-year period, requiring high-dose short-term treatments with systemic corticosteroids. Salmeterol MDI, ipratropium bromide MDI, and oral theophylline 200 mg twice a day were gradually added to his medication regimen without significant relief of his respiratory symptoms. Laboratory evaluation revealed a white blood cell count of 7900/mL with 24% eosinophils. Chest radiograph was normal. In view of persistent wheezing and systemic eosinophilia, stool specimens for ova and parasites were obtained and demonstrated S. stercoralis. The patient was treated with a 3-day course of oral albendazole at 400 mg twice a day. After successful treatment of intestinal strongyloidiasis, the patient’s asthma was completely under control without any medications.

This case illustrates that strongyloidiasis needs to be excluded in patients with unresponsive asthma, peripheral eosinophilia, and a history of living or traveling to endemic areas, even in the remote past.

CASE 3

A 78-year-old man, originally from Kentucky, presented to the emergency department for progressive shortness of breath. He had a history of myelodysplasia diagnosed several years prior to presentation. He never received chemotherapy or hemopoietic stem cell agents. However, he had been on continuous prednisone for 18 months and received supportive transfusions as necessary.

On examination, he was tachypneic but could speak in full sentences. He had a mild increase in jugular venous pressure, crackles bilaterally on lung examination, normal cardiac examination, and mild pedal edema. His complete blood count revealed pancytopenia without eosinophilia. Chest radiograph demonstrated diffuse bilateral infiltrates with Kerley B lines and small bilateral effusions. Empiric treatment of congestive heart failure failed to improve his condition. An echocardiogram was normal. The patient remained tachypneic, requiring 60% FIO2 via facemask to maintain an oxygen saturation of 90%. He underwent bronchoscopy, which was consistent with diffuse alveolar hemorrhage. Due to his deteriorating respiratory status, he required intubation and mechanical ventilation. Subsequently, the bronchoalveolar lavage revealed S. stercoralis. Treatment with thiabendazole began immediately. However, the patient died of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and multiple organ failure.

Cases 1 and 3 illustrate that disseminated strongyloidiasis can present without peripheral eosinophilia in immunocompromised patients. Prognosis tends to be grave in this patient population secondary to advanced disease process and delay in diagnosis due to low index of suspicion.

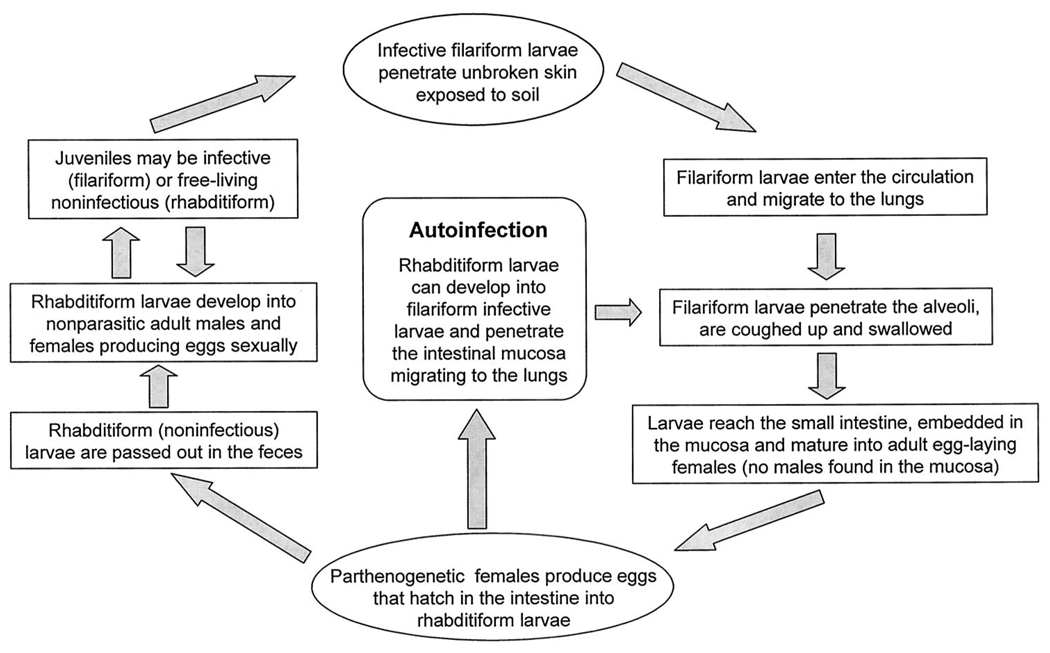

Pathogenesis and Lifecycle

The unique and unusual lifecycle of S. stercoralis displays many distinct biologic features that have important clinical implications (Fig. 2). The female worm can generate the progeny even without copulation with a male worm, a process called parthenogenesis, giving the species a survival advantage. The ability of S. stercoralis to cause serious disease is entirely due to the fact that the noninvasive and noninfectious rhabditiform larvae can mature directly into the invasive/infectious filariform larvae while still in the human intestine. This process, also known as autoinfection, eliminates the need of further exposure to exogenous infective larvae, allowing the infection to continue in the host many years after leaving an endemic area.1 In other terms, autoinfection is a cycle of endogenous reinfection within the host and is unique to S. stercoralis. Although the host’s immune mechanisms can keep the autoinfection under control, it cannot eradicate it. As a consequence, infection continues at a low worm burden to the host. As this control is lost in situations such as immunosuppression, ensuing accelerated autoinfection can lead to hyperinfection (high worm load) and dissemination.2

FIGURE 2.

Life cycle of Strongyloides stercoralis. See text for more detailed explanation.

The usual route of infection in humans is through skin contact with infective filariform larvae found in contaminated soil. After penetrating the skin, the filariform larvae travel through the circulatory system into the lungs and the alveoli, ascending to the upper airway and finally being swallowed to their final habitat, the small intestine. Female parasites, which are parthenogenetic, mature into adult egg-laying organisms in the upper small intestine. Egg deposition begins approximately 28 days after the initial infection. The eggs, initially deposited in the intestinal mucosa, hatch into the nonmigratory rhabditiform larvae. Most are excreted in the stool, but some metamorphose into the filariform larvae while in the gut, promoting autoinfection. The male parasites do not invade tissue and are excreted in the stool. Contrary to other helminthiases, the parasitic burden in strongyloidiasis is dependent on both the degree of autoinfection and larval inoculum. 2

Epidemiology

Strongyloidiasis is endemic in the tropical and subtropical areas of the world including southeast Asia, Latin America, and sub-Saharan Africa, affecting anywhere from 30 to 100 million people worldwide.3 In addition to being endemic in certain areas of southeastern United States,1,4–7 sporadic cases have been reported in many nonendemic urban centers with large immigrant populations. Higher infection rates may be seen in certain groups such as recent immigrants, war veterans, prison inmates, and residents of long-term care facilities.8,9

Clinical Features

As with other helminthiases, most infected individuals have low worm burden and are asymptomatic. Symptoms tend to occur sporadically with long asymptomatic periods in between.

Strongyloidiasis more commonly involves the gastrointestinal tract, skin, and respiratory tract. Most signs and symptoms are nonspecific. In a prospective study in rural Tennessee, patients most commonly complained of abdominal bloating (71%), abdominal pain (43%), and diarrhea (28%). Dyspnea, wheezing, and hemoptysis were present in 78%, 71%, and 14% of patients, respectively. Pruritus was present in 36% to 44% of patients.4 The pathognomonic rash of strongyloidiasis, larva currens or “racing larva,” occurs as the filariform larvae migrate in the skin, provoking intense pruritic urticarial wheal along its tortuous track.1

Respiratory manifestations of strongyloidiasis are protean (Table 1). During the migratory phase, the microfilariae migrate from pulmonary capillaries into the alveoli. This migration commonly leads to peripheral eosinophilia and elevated serum IgE levels.1 The clinical presentations in this phase include pulmonary infiltrates with eosinophilia syndrome10 or asthma without infiltrates.11–14 Another respiratory manifestation is the hyperinfection syndrome, during which there is accelerated autoinfection leading to wide-spread dissemination of the parasite. Hyperinfection tends to occur in patients with deficient cellular immunity. The clinical presentations in this phase include acute respiratory failure,15–17 lung abscess,18,19 cavitary lung disease,20 interstitial lung infiltrates, and fibrosis.21 The risk factors for development of hyperinfection are listed in Table 2. Hyperinfection is diagnosed when the larvae are recovered from extraintestinal sites. In a prospective study by Berk et al, 2 out of 23 patients with strongyloidiasis (8%) had hyperinfection.4

TABLE 1.

Pulmonary Manifestations of Strongyloidiaisis

| Pulmonary infiltrates with eosinophilia |

| Asthma without infiltrates |

| Hemoptysis due to alveolar hemorrhage |

| Hyperinfection syndrome |

| Acute respiratory distress syndrome |

| Lung abscess |

| Interstitial infiltrates/fibrosis |

| Cavitary lesions |

TABLE 2.

Risk Factors for Autoinfection and Hyperinfection with Strongyloides stercoralis

| Corticosteroid therapy |

| Immunosuppressive drug therapy |

| Chronic lung disease |

| HIV/AIDS |

| Chronic renal failure |

| Systemic rheumatoid disease |

| Solid tumor |

| Hematologic malignancy |

| Malnutrition |

| Achlorhydria |

| H2 blockers and antacids |

| Decreased gut motility |

Strongyloidosis and Asthma

Strongyloidiasis, with or without hyperinfection, has been associated with frequent asthma exacerbations. Improvement or resolution of asthma symptoms after adequate treatment of strongyloidiasis tends to be the norm.11–14,22 Although strongyloidiasis is a rare cause of asthma in the general population, it needs to be considered in patients who have lived in or traveled to endemic areas, even in the remote past. The importance of excluding this infection as a contributor or exacerbator of asthma is 2-fold: (1) complete resolution of asthma is likely to occur after adequate treatment of the infection; and (2) treatment with systemic corticosteroids has the potential risk of inducing hyperinfection.23 Investigators have hypothesized that parasitic infection can increase the burden of TH2 lymphocytes, leading to activation of inflammatory pathways in asthmatics.11

Asymptomatic Chronic Infection: Role of Screening

Most severe cases of pulmonary strongyloidiasis can be potentially prevented by early treatment during the asymptomatic chronic infection phase. Investigators have proposed screening patients with history of residence in endemic areas, especially if they have chronic respiratory diseases such as asthma or COPD and before initiating immunosuppression with chemotherapy or systemic corticosteroids.11,22 Currently, there are no scientific data to support screening for strongyloidiasis.

Is Strongyloidiasis More Common in Patients With Preexisting Lung Disease?

Several studies have shown a significant association between strongyloidiasis and coexisting lung disease.5,22,24 In a prospective screening study by Berk et al,4 86% of patients with stool positive for S. stercoralis had coexisting chronic lung disease, while only 52% had underlying lung disease in the stool-negative control population. There are 2 possible explanations for this association. A delay in the transit of the filariform larvae through the lungs may occur because of structural abnormalities such as fibrosis or mucus plugging, allowing the larvae to mature into egg-laying adult worms in the lungs. Another contributing factor could be the more frequent use of corticosteroids and immunosuppressive agents in patients with underlying lung disease, thereby accelerating the autoinfection and setting the stage for hyperinfection.

Strongyloidosis and HIV

Many case reports and several case series of strongyloidiasis in HIV patients have demonstrated higher rates of disseminated infection, lower frequency of eosinophilia, poor response to thiabendazole, and higher mortality rate compared with non-HIV patients.24–28 Whether HIV infection is a risk factor for autoinfection or hyperinfection remains to be elucidated. In a study of 696 patients from an endemic area for S. stercoralis there was no difference in the prevalence of larvae in fecal samples from patients with AIDS (9.75%) versus control patients without HIV/AIDS (10.5%).29 A retrospective Brazilian study of 650 HIV-positive patients during a 77 month period identified 25 cases (4%) of strongyloidiasis. However, hyperinfection occurred in 28% of patients with strongyloidiasis.28

Diagnosis of Pulmonary Infection

The diagnosis of strongyloidiasis is often delayed largely due to nonspecific clinical signs and symptoms and radiographic findings.30 Most patients with strongyloidiasis are asymptomatic or have mild gastrointestinal symptoms.5 The lung is the most common extraintestinal organ involved in disseminated strongyloidiasis. In patients with chronic underlying pulmonary disease, the symptoms of strongyloidiasis are usually interpreted as an exacerbation of the preexisting condition rather than a parasitic infection. In many instances patients are treated with increasing doses of systemic corticosteroids. Immunosuppression induced by corticosteroids can potentially lead to worsening of nondisseminated infection4,5 and hyperinfection syndrome.31 The diagnosis of disseminated strongyloidiasis requires a high index of suspicion. Important clinical clues include history of travel or prior residence in an endemic area, even in the remote past. A combination of chronic lung disease such as unresponsive asthma or unexplained lung infiltrates together with gastrointestinal symptoms may be suggestive of strongyloidiasis. 1,6 Gram negative septicemia or Gram negative bacterial meningitis may develop due to breakdown of the normal gut mucosal barrier.2,24,32 Peripheral blood eosinophilia in association with pneumonia, bronchospasm, bronchitis, abdominal pain, or diarrhea is highly suggestive of strongyloidiasis in patients who have lived or traveled to endemic areas. Eosinophilia of more than 5% has been reported in 65% to 90% of patients with mean eosinophil percentage between 13% and 18%.5,22,30,33 However, peripheral blood eosinophilia may be absent in patients with hyperinfection syndrome, possibly due to suppression of eosinophils by either corticosteroids or associated bacterial infection.27 Absence of eosinophilia is considered to be a poor prognostic sign.23,34,35

Although normal chest radiograph has been reported in patients with pulmonary strongyloidiasis, most patients have abnormal findings (Table 3). In patients with autoinfection, the migration of larvae from capillary beds into the alveoli produces a foreign body reaction, inflammatory pneumonitis, and pulmonary hemorrhage. During the initial phases of the infection the chest radiograph and CT-scan show fine miliary nodules or diffuse reticular infiltrates. As the infection progresses, patchy and diffuse lobar infiltrates can develop. In patients with preexisting lung disease and in those with the hyperinfection syndrome, massive larval migration through the lungs can lead to extensive lung infiltration and development of ARDS.6,30

TABLE 3.

Radiographic Findings Associated With Pulmonary Strongyloidiaisis

| Radiographic Findings (References)* | Pooled Data of 29 Cases From Several Case Reports (n) |

Case Series of 20 Patients (Ref 6) |

|---|---|---|

| Initial normal CXR (11,15,20–24,35) | 27% (8) | 5% (1) |

| Diffuse alveolar opacities (23, 24, 36–38) | 17% (5) | 45% (9) |

| Segmental/lobar infiltrate (25,37) | 7% (2) | 30% (6) |

| Interstitial infiltrates (16,18,24,27,39) | 17% (5) | 35% (7) |

| Migratory opacities | 0 | 0 |

| Pleural effusion (37) | 3% (1) | 40% (8) |

| Abscess/cavitation (18–20) | 10% (3) | 15% (3) |

| ARDS (16,18) | 7% (2) | 45% (9) |

| Mediastinal lymphadenopathy (37) | 3% (1) | 5% (1) |

| Fibrotic changes (21) | 3% (1) | 0 |

| Microlithiasis (40) | 3% (1) | 0 |

Total percentages can be higher than 100% as patients may have had different radiologic manifestations.

Definitive diagnosis is dependent upon demonstration of S. stercoralis larvae (Table 4). The larvae are most commonly detected in stool. However, in many uncomplicated cases the intestinal parasite load is low, with minimal larvae output.1 A single stool examination for ova and parasites detects larvae in only 30% of cases. The diagnostic sensitivity of stool ova and parasite examination can increase to 50% with 3 samples and near 100% with 7 samples obtained serially.41,42 Duodenal aspirates or jejunal biopsy specimens are highly sensitive and show evidence of S. stercoralis in up to 90% of cases.43,44 In disseminated infections, the detection of S. stercoralis larvae becomes easier due to overwhelming number of organisms present. The organism can be recognized on Papanicolaou-stained smears of sputum submitted for routine cytopathology.36 The use of sputum Gram stain has been described as a useful test to screen for pulmonary strongyloidiasis in steroid-treated patients with lung disease from an endemic area.38 Strongyloides stercoralis has also been detected on specimens obtained by transtracheal aspirate, 45 bronchial washing or bronchoalveolar lavage,17,23,38,39 and transbronchial or open lung biopsy.15 The sensitivity of these tests in diagnosis of pulmonary strongyloidiasis has not been studied.

TABLE 4.

Sensitivity of Diagnostic Tests for Strongyloidiasis*

| Intestinal Strongyloidiasis | Hyperinfection Syndrome | |

|---|---|---|

| Eosinophilia | 60%–90% | < 20% |

| Stool ova and parasite | ||

| Single stool exam | 20%–30% | > 30% |

| ≥ 3 stool exam | 60%–70% | > 80% |

| 7 stool exam | > 95% | 95%–100% |

| Duodenal samples | 40%–90% | ?, Moderate to high |

| Sputum/BAL | ?, very low | ?, Moderate to high |

| Serologic tests | ||

| ELISA (IgG to S. stercoralis antigen) | 80%–90% | ? |

Specificity is unknown for most of these tests. ? Refers to unknown.

An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) that can detect serum IgG against S. stercoralis has been developed and is available in specialized centers. It appears to have a sensitivity of 88%, specificity of 99%, and negative predictive value above 95%. Its positive predictive value can be low in endemic areas. Although filariasis, acute schistosomiasis, and ascariasis are rare in North America, they can cross-react IgG against S. stercoralis detected by ELISA.46 The limitations of this test include lack of availability in most laboratories, inability to distinguish between past or current infections as antibody levels remain detectable for years after treatment, and inability to provide a quantitative assessment of the worm burden. Serologic testing becomes more useful if used in patients at risk for strongyloidiasis and if positive it can stimulate a more thorough search for the parasite.47

Treatment

Treatment of strongyloidiasis can be challenging. Complete cure involves total eradication of all viable parasites. Achieving this goal is difficult since any surviving organism can potentially create a cycle of endogenous reinfection (autoinfection). Furthermore, the invasive/infectious filariform larvae are relatively resistant to antiparasitic agents.1,2 Demonstrating a complete cure is difficult by currently available diagnostic testing. Single stool examination has a low sensitivity, and antibody levels measured by ELISA remain detectable for years after treatment.

Thiabendazole, available in tablets or oral suspension, had been considered the drug of choice for treatment of strongyloidiasis. For a simple infection, the recommended dose is 25 mg/kg in 3 divided doses for 2 to 3 consecutive days. In hyperinfection syndrome or in patients with chronic lung disease, treatment is extended for 7 to 10 days. Thiabendazole’s efficacy is limited by high relapse rates, even in low-grade infections.48 Up to 30% of patients report an adverse effect such as nausea, dizziness, pruritus, headache, visual disturbances, and neuropsychiatric reactions.48

Newer and more effective antihelminthic agents include albendazole and ivermectin. In a comprehensive Peruvian trial, 2 consecutive daily doses of ivermectin at 200 µg/kg was superior to a single dose.49 Gann et al50 randomized 53 subjects with chronic strongyloidiasis to 3 groups: 1 dose of 200 µg/kg of ivermectin, 2 consecutive doses of ivermectin, or 3 consecutive days of thiabendazole. Cure was confirmed by 3 stool samples, and all patients had a minimum of 3 months of follow-up. Although cure rates were similar between all 3 groups, nearly 95% of patients receiving thiabendazole experienced side effects compared with only 18% of those treated with ivermectin. A recent Japanese trial of 211 patients with uncomplicated strongyloidiasis demonstrated a cure rate of 97% with single dose ivermectin versus a cure rate of 77% with 3 consecutive days of albendazole.51 Other human trials have reported cure rates of 38% to 81% with albendazole with few side effects.52–54 Datry et al54 reported parasitological cure in 83% of patients with uncomplicated strongyloidiasis treated with single dose of ivermectin compared with 38% treated with a 3-day course of albendazole. Ivermectin appears to be superior to albendazole and thiabendazole. Single-dose treatment and fewer side effects contribute to improved compliance when compared with other antiparasitic agents. Furthermore, it appears to be safe in pregnancy,55 and it has also been effective in patients with chronic strongyloidiasis who have failed several courses of thiabendazole.56,57 Currently, there are no systematic studies evaluating the efficacy of ivermectin in hyperinfection or disseminated strongyloidiasis. Its use, either as single dose or multiple doses, has been limited to case reports and small case series.58,59

Prognosis

Almost all deaths due to helminthic infection in the United States are secondary to disseminated strongyloidiasis or hyperinfection syndrome.60,61 Mortality rates as high as 86% have been reported in disseminated infection.32 A mortality rate of 90% was reported in a retrospective study of 10 patients with HIV and disseminated strongyloidiasis. However, none of these patients received ivermectin.27 In a prospective study of 27 patients with hyperinfection syndrome, of which 71% were HIV-positive, mortality rate was 26%. High mortality rates have also been reported in patients who develop ARDS,30 have baseline chronic lung disease,22 or develop bacteremia.62

REFERENCES

- 1.Liu LX, Weller PF. Strongyloidiasis and other intestinal nematode infections. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1993;7:655–682. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grove DI. Human strongyloidiasis. Adv Parasitol. 1996;38:251–309. doi: 10.1016/s0065-308x(08)60036-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Genta RM. Global prevalence of strongyloidiasis: critical review with epidemiologic insights into the prevention of disseminated disease. Rev Infect Dis. 1989;11:755–767. doi: 10.1093/clinids/11.5.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berk SL, Verghese A, Alvarez S, et al. Clinical and epidemiologic features of strongyloidiasis: a prospective study in rural Tennessee. Arch Intern Med. 1987;147:1257–1261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davidson RA, Fletcher RH, Chapman LE. Risk factors for strongyloidiasis: a case-control study. Arch Intern Med. 1984;144:321–324. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1984.00350140135019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Woodring JH, Halfhill H, Reed JC. Pulmonary strongyloidiasis: clinical and imaging features. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1994;162:537–542. doi: 10.2214/ajr.162.3.8109492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walzer PD, Milder JE, Banwell JG, et al. Epidemiologic features of Strongyloides stercoralis infection in an endemic area of the United States. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1982;31:313–319. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1982.31.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Braun TI, Fekete T, Lynch A. Strongyloidiasis in an institution for mentally retarded adults. Arch Intern Med. 1988;148:634–636. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Genta RM, Weesner R, Douce RW, et al. Strongyloidiasis in US veterans of the Vietnam and other wars. JAMA. 1987;258:49–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sharma OP. Diagnosing pulmonary infiltration with eosinophilia syndrome, part 1. J Respir Dis. 2002;23:411–420. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Robinson J, Ahmed Z, Siddiqui A, et al. A patient with persistent wheezing, sinusitis, elevated IgE, and eosinophilia. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 1999;82:144–149. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)62588-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dunlap NE, Shin MS, Polt SS, et al. Strongyloidiasis manifested as asthma. South Med J. 1984;77:77–78. doi: 10.1097/00007611-198401000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Higenbottam TW, Heard BE. Opportunistic pulmonary strongyloidiasis complicating asthma treated with steroids. Thorax. 1976;31:226–233. doi: 10.1136/thx.31.2.226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nwokolo C, Imohiosen EA. Strongyloidiasis of respiratory tract presenting as “asthma”. BMJ. 1973;2:153–154. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5859.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Venizelos PC, Lopata M, Bardawil WA, et al. Respiratory failure due to Strongyloides stercoralis in a patient with a renal transplant. Chest. 1980;78:104–106. doi: 10.1378/chest.78.1.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thompson JR, Berger R. Fatal adult respiratory distress syndrome following successful treatment of pulmonary strongyloidiasis. Chest. 1991;99:772–774. doi: 10.1378/chest.99.3.772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cook GA, Rodriguez H, Silva H, et al. Adult respiratory distress secondary to strongyloidiasis. Chest. 1987;92:1115–1116. doi: 10.1378/chest.92.6.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ford J, Reiss-Levy E, Clark E, et al. Pulmonary strongyloidiasis and lung abscess. Chest. 1981;79:239–240. doi: 10.1378/chest.79.2.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seabury JH, Abadie S, Savoy F., Jr Pulmonary strongyloidiasis with lung abscess: ineffectiveness of thiabendazole therapy. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1971;20:209–211. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1971.20.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pettersson T, Stenstrom R, Kyronseppa H. Disseminated lung opacities and cavitation associated with Strongyloides stercoralis and Schistosoma mansoni infection. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1974;23:158–162. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1974.23.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin AL, Kessimian N, Benditt JO. Restrictive pulmonary disease due to interlobular septal fibrosis associated with disseminated infection by Strongyloides stercoralis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;151:205–209. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.151.1.7812554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davidson RA. Infection due to Strongyloides stercoralis in patients with pulmonary disease. South Med J. 1992;85:28–31. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199201000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Upadhyay D, Corbridge T, Jain M, et al. Pulmonary hyperinfection syndrome with Strongyloides stercoralis. Am J Med. 2001;111:167–169. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(01)00708-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kramer MR, Gregg PA, Goldstein M, et al. Disseminated strongyloidiasis in AIDS and non-AIDS immunocompromised hosts: diagnosis by sputum and bronchoalveolar lavage. South Med J. 1990;83:1226–1229. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199010000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maayan S, Wormser GP, Widerhorn J, et al. Strongyloides stercoralis hyperinfection in a patient with the acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Am J Med. 1987;83:945–948. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(87)90656-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sarangarajan R, Ranganathan A, Belmonte AH, et al. Strongyloides stercoralis infection in AIDS. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 1997;11:407–414. doi: 10.1089/apc.1997.11.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lessnau KD, Can S, Talavera W. Disseminated Strongyloides stercoralis in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients: treatment failure and a review of the literature. Chest. 1993;104:119–122. doi: 10.1378/chest.104.1.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ferreira MS, Nishioka S, Borges AS, et al. Strongyloidiasis and infection due to human immunodeficiency virus: 25 cases at a Brazilian teaching hospital, including seven cases of hyperinfection syndrome. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;28:154–155. doi: 10.1086/517188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dias RM, Mangini AC, Torres DM, et al. Occurrence of Strongyloides stercoralis in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 1992;34:15–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Woodring JH, Halfhill H, 2nd, Berger R, et al. Clinical and imaging features of pulmonary strongyloidiasis. South Med J. 1996;89:10–19. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199601000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scowden EB, Schaffner W, Stone WJ. Overwhelming strongyloidiasis: an unappreciated opportunistic infection. Medicine (Baltimore) 1978;57:527–544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Igra-Siegman Y, Kapila R, Sen P, et al. Syndrome of hyperinfection with Strongyloides stercoralis. Rev Infect Dis. 1981;3:397–407. doi: 10.1093/clinids/3.3.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barrett-Connor E. Parasitic pulmonary disease. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1982;126:558–563. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1982.126.3.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilson S, Thompson AE. A fatal case of strongyloidiasis. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1964;87:169–176. doi: 10.1002/path.1700870123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Giannoulis E, Arvanitakis C, Zaphiropoulos A, et al. Disseminated strongyloidiasis with uncommon manifestations in Greece. J Trop Med Hyg. 1986;89:171–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Humpherys K, Hieger LR. Strongyloides stercoralis in routine Papanicolaou-stained sputum smears. Acta Cytol. 1979;23:471–476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bruno P, McAllister K, Matthews JI. Pulmonary strongyloidiasis. South Med J. 1982;75:363–365. doi: 10.1097/00007611-198203000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smith B, Verghese A, Guiterrez C, et al. Pulmonary strongyloidiasis: diagnosis by sputum gram stain. Am J Med. 1985;79:663–666. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(85)90068-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Williams J, Nunley D, Dralle W, et al. Diagnosis of pulmonary strongyloidiasis by bronchoalveolar lavage. Chest. 1988;94:643–644. doi: 10.1378/chest.94.3.643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Makris AN, Sher S, Bertoli C, et al. Pulmonary strongyloidiasis: an unusual opportunistic pneumonia in a patient with AIDS. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1993;161:545–547. doi: 10.2214/ajr.161.3.8352101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nielsen PB, Mojon M. Improved diagnosis of Strongyloides stercoralis by seven consecutive stool specimens. Zentralbl Bakteriol Mikrobiol Hyg [A] 1987;263:616–618. doi: 10.1016/s0176-6724(87)80207-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pelletier LL., Jr Chronic strongyloidiasis in World War II: Far East ex-prisoners of war. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1984;33:55–61. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1984.33.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Goka AK, Rolston DD, Mathan VI, et al. Diagnosis of Strongyloides and hookworm infections: comparison of faecal and duodenal fluid microscopy. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1990;84:829–831. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(90)90098-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Beal CB, Viens P, Grant RG, et al. A new technique for sampling duodenal contents: demonstration of upper small-bowel pathogens. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1970;19:349–352. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1970.19.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Scoggin CH, Call NB. Acute respiratory failure due to disseminated strongyloidiasis in a renal transplant recipient. Ann Intern Med. 1977;87:456–458. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-87-4-456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Genta RM. Predictive value of an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for the serodiagnosis of strongyloidiasis. Am J Clin Pathol. 1988;89:391–394. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/89.3.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Siddiqui AA, Berk SL. Diagnosis of Strongyloides stercoralis infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33:1040–1047. doi: 10.1086/322707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Grove DI. Treatment of strongyloidiasis with thiabendazole: an analysis of toxicity and effectiveness. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1982;76:114–118. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(82)90034-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Naquira C, Jimenez G, Guerra JG, et al. Ivermectin for human strongyloidiasis and other intestinal helminths. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1989;40:304–309. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1989.40.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gann PH, Neva FA, Gam AA. A randomized trial of single- and two-dose ivermectin versus thiabendazole for treatment of strongyloidiasis. J Infect Dis. 1994;169:1076–1079. doi: 10.1093/infdis/169.5.1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Toma H, Sato Y, Shiroma Y, et al. Comparative studies on the efficacy of three anthelminthics on treatment of human strongyloidiasis in Okinawa, Japan. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2000;31:147–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rossignol JF, Maisonneuve H. Albendazole: placebo-controlled study in 870 patients with intestinal helminthiasis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1983;77:707–711. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(83)90211-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Archibald LK, Beeching NJ, Gill GV, et al. Albendazole is effective treatment for chronic strongyloidiasis. Q J Med. 1993;86:191–195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Datry A, Hilmarsdottir I, Mayorga-Sagastume R, et al. Treatment of Strongyloides stercoralis infection with ivermectin compared with albendazole: results of an open study of 60 cases. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1994;88:344–345. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(94)90110-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pacque M, Munoz B, Poetschke G, et al. Pregnancy outcome after inadvertent ivermectin treatment during community-based distribution. Lancet. 1990;336:1486–1489. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)93187-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lyagoubi M, Datry A, Mayorga R, et al. Chronic persistent strongyloidiasis cured by ivermectin. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1992;86:541. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(92)90100-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wijesundera MD, Sanmuganathan PS. Ivermectin therapy in chronic strongyloidiasis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1992;86:291. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(92)90315-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Torres JR, Isturiz R, Murillo J, et al. Efficacy of ivermectin in the treatment of strongyloidiasis complicating AIDS. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;17:900–902. doi: 10.1093/clinids/17.5.900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chiodini PL, Reid AJ, Wiselka MJ, et al. Parenteral ivermectin in Strongyloides hyperinfection. Lancet. 2000;355:43–44. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)02744-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Muennig P, Pallin D, Sell RL, et al. The cost effectiveness of strategies for the treatment of intestinal parasites in immigrants. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:773–779. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199903113401006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mitre E. Treatment of intestinal parasites in immigrants. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:377–378. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199907293410518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Link K, Orenstein R. Bacterial complications of strongyloidiasis: Streptococcus bovis meningitis. South Med J. 1999;92:728–731. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199907000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]