Abstract

Triacylglycerols (TAGs), wax esters (WEs), and polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) are the major hydrophobic compounds synthesized in bacteria and deposited as cytoplasmic inclusion bodies when cells are cultivated under imbalanced growth conditions. The intracellular occurrence of these compounds causes high costs for downstream processing. Alcanivorax species are able to produce extracellular lipids when the cells are cultivated on hexadecane or pyruvate as the sole carbon source. In this study, we developed a screening procedure to isolate lipid export-negative transposon-induced mutants of bacteria of the genus Alcanivorax for identification of genes required for lipid export by employing the dyes Nile red and Solvent Blue 38. Three transposon-induced mutants of A. jadensis and seven of A. borkumensis impaired in lipid secretion were isolated. All isolated mutants were still capable of synthesizing and accumulating these lipids intracellularly and exhibited no growth defect. In the A. jadensis mutants, the transposon insertions were mapped in genes annotated as encoding a putative DNA repair system specific for alkylated DNA (Aj17), a magnesium transporter (Aj7), and a transposase (Aj5). In the A. borkumensis mutants, the insertions were mapped in genes encoding different proteins involved in various transport processes, like genes encoding (i) a heavy metal resistance (CZCA2) in mutant ABO_6/39, (ii) a multidrug efflux (MATE efflux) protein in mutant ABO_25/21, (iii) an alginate lyase (AlgL) in mutants ABO_10/30 and ABO_19/48, (iv) a sodium-dicarboxylate symporter family protein (GltP) in mutant ABO_27/29, (v) an alginate transporter (AlgE) in mutant ABO_26/1, or (vi) a two-component system protein in mutant ABO_27/56. Site-directed MATE, algE, and algL gene disruption mutants, which were constructed in addition, were also unable to export neutral lipids and confirmed the phenotype of the transposon-induced mutants. The putative localization of the different gene products and their possible roles in lipid excretion are discussed. Beside this, the composition of the intra- and extracellular lipids in the wild types and mutants were analyzed in detail.

Almost all prokaryotes synthesize lipophilic storage substances as an integral part of their metabolism under limited nitrogen or phosphorus conditions if there is an excess of a suitable carbon source at the same time. The accumulated storage lipids serve as energy and carbon sources during starvation periods, and they are mobilized again under conditions of carbon and energy deficiency. The majority of the members of many genera synthesize hydrophobic polymers, such as poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) (PHB) or other types of polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs), whereas the accumulation of triacylglycerols (TAGs; trioxoesters of glycerol and long-chain fatty acids [FAs]) or wax esters (WEs; oxoesters of primary long-chain fatty acids and primary long-chain fatty alcohols) occurs in fewer prokaryotes (66). TAG accumulation has been reported for species of the genera Streptomyces, Mycobacterium, Nocardia, Rhodococcus (4, 6, 65), and recently also Alcanivorax and other hydrocarbonoclastic marine bacteria (32). Accumulation of WEs has been frequently reported for species of the genus Acinetobacter (66) but also for marine bacteria, such as Marinobacter (50) and Alcanivorax (11, 32).

In general, the accumulation of at least one type of these compounds occurs intracellularly under imbalanced growth conditions in almost all prokaryotes. The localization of neutral lipids in marine organisms is not restricted to the cell cytoplasm, as extracellular lipid deposition has been shown in studies with Alcaligenes sp. PHY9 and Pseudomonas nautica (24). The production of extracellular wax esters by Alcanivorax jadensis T9 growing on hexadecane was described a few years ago (11). Species of the genus Alcanivorax belong to an unusual group of marine hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria, which have been recognized and described over the past few years and were shown to play an important role in the biological removal of petroleum hydrocarbons from contaminated sites (69). Species of the genus Alcanivorax are, like some species of the genera Neptunomonas (27) and Marinobacter (23), marine hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria. Moreover, Alcanivorax and related bacteria constitute the group of obligate hydrocarbonoclastic marine bacteria (OHCB), which exhibit a narrow range of utilizable carbon sources (obligate hydrocarbon utilization), with only a few species being able to metabolize substrates other than hydrocarbons (69). Alcanivorax borkumensis SK2 became a model strain of OHCB, and its importance and pivotal role in hydrocarbon biodegradation have recently been emphasized (33). The predominance of A. borkumensis in early stages of petroleum degradation has also been reported in microcosm studies as well as for a field-scale experiment (26).

From a biotechnological point of view, the production of extracellular lipids is important. Secretion of lipophilic products into the culture medium rather than its intracellular accumulation can significantly reduce the costs of product recovery. Another advantage is that the production of WEs and TAGs would not be directly limited by cell density or cell volume. Until now, the mechanism responsible for the export of lipids in bacteria of the genus Alcanivorax or other bacteria had not been known. In this study, we report on a screening procedure to select mutants defective in lipid export for identification of the gene(s) involved in the export mechanism. After transposon-induced mutagenesis we found different mutants which were not able to export TAGs (mutants of A. borkumensis) when the cells were cultivated in the presence of pyruvate as the sole carbon source. Mutants of A. jadensis defective in export of WEs and/or wax diesters (DE) were also identified. The possible influences of the gene products on the export mechanism in Alcanivorax species were analyzed and are discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, media, and cultivation conditions.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Cells of A. borkumensis were cultivated aerobically at 30°C and 150 rpm for 60 h in ONR7a medium (19) containing 1% (wt/vol) sodium pyruvate or 0.5% (wt/vol) hexadecane as the sole carbon source. Cells of A. jadensis were cultivated at 30°C and 150 rpm for 96 h in artificial seawater (MWM medium [13]). Acinetobacter baylyi strain ADP1 was cultivated in mineral salts medium (MSM [56]) with 1% (wt/vol) sodium gluconate as the carbon source. Escherichia coli strains were cultivated in lysogeny broth (LB) medium at 37°C (53). cLB mating medium used for a biparental filter-mating technique is a modified LB containing per liter 10 g tryptone, 5 g yeast extract, 0.45 g Na2HPO4·H2O, 2.5 g NaNO3, 16.5 g NaCl, 0.38 g KCl, and 0.7 g CaCl2·H2O and 2% (wt/vol) sodium pyruvate as the carbon source. Cultures were inoculated with 1% (vol/vol) of cells growing in the exponential growth phase. If appropriate, antibiotics were used in the following concentrations: ampicillin (Ap), 75 mg/liter; kanamycin (Km), 50 mg/liter; chloramphenicol (Cm), 34 mg/liter; nalidixic acid (Ndx), 10 mg/liter; streptomycin (Sm), 100 mg/liter; and tetracycline (Tc), 12.5 mg/liter.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristicsa | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Alcanivorax borkumensis strains | ||

| SK2 | Type strain, wild type; TAG and WE producer | 68; DSM 11573 |

| SK2 algLΩSm | algL disruption mutant; Smr; derivative of SK2 | This study |

| SK2 algEΩSm | algE disruption mutant; Smr; derivative of SK2 | This study |

| SK2 MATEΩSm | MATE disruption mutant; Smr; derivative of SK2 | This study |

| Alcanivorax jadensis T9 | Type strain, wild type; TAG and WE producer | 13, 21; DSM 12178 |

| Acinetobacter baylyi ADP1 | TAG and WE producer | 31 |

| Escherichia coli strains | ||

| SM10 (λpyr) | Apr, Cmr, Kmr, pUTminiTn5Cm | 16 |

| TOP10 | F−mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS mcrBC) rpcL nupG endA1 deoR φ80lacZΔM15 ΔlacX74 recA1 araD139 Δ(ara-leu)7697 galU galK | Invitrogen |

| LE 392 | λ-rpsL(Smr) nupG F−hsdR574 (rK− mK+) supE44 supF58 lacY1 or Δ(lacIZY)6 galK2 galT22 metB1 trpR55 | Promega |

| XL1-Blue | recA1 endA gyrA96 thi1 hsdR17 (rK− mK+) supE44 relA1 λ−lac [F′ proAB lacIqZΔM15 Tn10(Tcr)] | 14 |

| S17-1 | recA1 thi1 hsdR17 (rK− mK+) proA tra (RP4) | 59 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pBluescript SK (−) | Plasmid used for subcloning DNA, Apr, lacPOZ′ | Stratagene |

| pUTminiTn5Cm | Suicide vector for mutagenesis with miniTn5, Cmr | 16 |

| pHC79 | Cosmid, Apr Tcr | 29 |

| pET19b | Apr, T7 promoter-based expression vector | Novagen |

| pET19b::algE | Derivative of pET19b containing the algE gene as 1,380bp HindIII fragment, Apr | This study |

| pET19b::algEΩSm | ΩSmr cassette cloned into SalI site of pET19b::algE, Apr Smr | This study |

| pUC19 | Cloning vector, Apr | 53 |

| pUC19::algL | Derivative of pUC19 containing the algL gene as 1,041-bp BamHI/HindIII fragment, Apr | This study |

| pUC19::algLΩSm | ΩSmr cassette cloned into NcoI site of pUC19::algL, Apr Smr | This study |

| pUC19::MATE | Derivative of pUC19 containing the MATE gene as 1,287-bp BamHI/HindIII fragment Apr | This study |

| pUC19::MATE:: ΩSm | ΩSmr cassette cloned into NcoI site of pUC19::algL, Apr Smr | This study |

| pSUP202 | Apr Cmr Tcr; ColE1 origin; mob site; unable to replicate in A. borkumensis | 59 |

| pSUP202:: algEΩSm | Fusion of pSUP202 and algEΩSm fragment of pET19b::algEΩSm via HindIII site; mob site, Cmr Apr Smr | This study |

| pSUP202:: algLΩSm | Fusion of pSUP202 and algLΩSm fragment of pUC19::algLΩSm via BamHI/HindIII sites; mob site, Cmr Apr Smr | This study |

| pSUP202:: MATEΩSm | Fusion of pSUP202 and MATEΩSm fragment of pUC19::MATEΩSm via BamHI/HindIII sites; mob site. Cmr Apr Smr | This study |

For abbreviations for genotypes of E. coli, see reference 7. Apr, ampicillin resistant; Cmr, chloramphenicol resistant; Smr, streptomycin resistant; Tcr, tetracycline resistant.

Construction of A. borkumensis SK2 and A. jadensis T9 mini-Tn5 transposon libraries.

Transposon-induced mutants of Alcanivorax strains were generated using the mini-Tn5 Cm element constructed as described previously (16) by employing a biparental filter-mating technique. A. borkumensis was grown on ONR7a medium at 30°C and harvested in the stationary growth phase by centrifugation at 4,000 rpm for 50 min and 4°C. A. jadensis was grown in MWM medium at 30°C until reaching the stationary phase (about 72 h). Then the cells were harvested by centrifugation at 4,000 rpm and 4°C for 30 min. The donor strain E. coli SM10(λpyr) containing the pUTmini-Tn5Cm vector was grown overnight at 37°C in LB medium with Cm. Cells were harvested, washed once with cLB mating medium, and concentrated 10-fold in the same medium. The pellets of A. borkumensis (recipient) and E. coli (donor) were mixed 4:1 (vol/vol), or 2:1 (vol/vol) in the case of A. jadensis (recipient) and E. coli (donor). Dilutions of the A. borkumensis-E. coli or A. jadensis-E. coli cell mixtures were spotted on a nitrocellulose membrane filter (diameter, 45 mm; pore size, 0.45 μm; Millipore) which was then placed on cLB mating agar or MWM agar (MWM medium containing 18 g/liter agar and 2% [wt/vol] sodium pyruvate) plates, respectively. In both cases, plates were incubated at 30°C for 24 h. After this time, cells were washed from the filter with 10 mM MgSO4 and resuspended, and transconjugants were selected on ONR7a (for A. borkumensis) or MWM (A. jadensis) selection plates containing appropriate antibiotics for selection of transconjugants and for inhibition of E. coli (Ndx and Cm). Hexadecane applied on a filter paper in the lid was used as carbon and energy source. After 7 days of incubation at 30°C, the resulting transconjugants of both Alcanivorax strains were transferred and patched onto selective agar plates containing different antibiotics to select mutants defective in lipid biosynthesis and/or export, as described below in more detail.

Screening method to identify lipid export-negative mutants.

To select mutants defective in lipid metabolism, ONR7a selection plates containing Cm and Ndx as selective antibiotics and also containing either Nile red (NR; 0.5 μg/ml) or the lipophilic stain Solvent Blue 38 (SB38; 0.005% [wt/vol]), or plates containing a combination of both dyes were used. The use of NR for identification of strains defective in lipid production was described previously (62). In the same way, SB38 (also known as Luxol fast blue) is a lipophilic stain used in medical studies to stain myelin (37). After 5 days incubation, the plates were analyzed under UV light, and transconjugants without or with decreased fluorescence were selected for further analysis.

Analysis of lipids by TLC.

The analysis of intra- and extracellular lipids was done by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) as follows. Cells of Alcanivorax were harvested after 72 h cultivation by centrifugation for 30 min at 7,000 rpm and 4°C and were thereby separated into a pellet and a supernatant fraction. The cells were washed with 10 mM MgSO4, centrifuged again, and lyophilized. Intracellular lipids were extracted from 5 mg (dry weight) cell material. Extracellular lipids were extracted directly from the supernatant fraction (corresponding to the amount of dry cell material to analyze), which was mixed with the same volume of chloroform-methanol (2:1 [vol/vol]) and vortexed. After separation of the two phases, the organic phase was removed and analyzed for extracted lipids. TLC analysis of lipid extracts was done using the solvent system hexane-diethyl ether-acetic acid (80:20:1 [vol/vol/vol] or 90:7.5:1 [vol/vol/vol]). Lipids were visualized on the plates by staining with iodine vapor. Triolein, oleic acid, and oleyl oleate were used as reference substances for TAGs, FAs, and WEs, respectively.

Quantitative determination of intra- and extracellular lipids by preparative TLC and fatty acid analysis.

For quantification of intra- and extracellular lipids, preparative TLC and subsequent fatty acid analysis by gas chromatography (GC) was performed. For this, the lipid extracts of both cells and the corresponding amount of supernatant were resolved by TLC, and spots corresponding to TAGs and WEs were scraped from the plates and subjected to sulfuric acid-catalyzed methanolysis. For quantitative analysis, tridecanoic acid was added to the samples before performing the acidified methanolysis as an internal standard. Fatty acid methyl esters were analyzed using an Agilent 6850 GC (Agilent Technologies, Waldbronn, Germany) equipped with a BP21 capillary column (50 m by 0.22 mm; film thickness, 250 nm; SGE, Darmstadt, Germany) and a flame ionization detector (Agilent Technologies, Waldbronn, Germany). A 2-μl portion of the organic phase was analyzed after split injection (20:1); hydrogen (constant flow, 0.6 ml min−1) was used as a carrier gas. The temperatures of the injector and detector were 250°C and 275°C, respectively. The following temperature program was applied: 120°C for 5 min, increase of 3°C min−1 to 180°C, increase of 10°C min−1 to 220°C, and 220°C for 31 min. Substances were identified by comparison of their retention times with those of authentic standard fatty acid methyl esters.

Identification of lipids other than TAGs or WEs.

Lipid extracts were separated and recovered from the chromatogram using a ChromeXtract (ChromAn, Leipzig, Germany). Intra- and extracellular lipids of A. jadensis T9 were analyzed by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI/MS) and ESI/tandem MS (MS2) in the positive-ion mode on a Quattro LCZ (Waters-Micromass, Manchester, United Kingdom) with stating nanospray using capillary with internal wire contact.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM).

Ultrathin sections of Alcanivorax strain cells were analyzed as described previously (32).

Genotypical characterization of mini-Tn5-induced mutants of Alcanivorax species.

The mini-Tn5 insertion sites in transconjugants of A. borkumensis were determined as described previously (51).

Transposon insertion sites in transconjugants of A. jadensis were mapped by cosmid libraries, which were constructed as follows: genomic DNA of the mini-Tn5 mutants was digested with PstI, and the resulting fragments were ligated into cosmid pHC79. The cosmids were packaged into phage heads, and cells of E. coli LE392 were then infected according to the manufacturer's instructions (Packagene Lambda DNA Packaging System, Promega, Mannheim, Germany). Subsequently, recombinant E. coli LE392 clones were selected on LB agar plates containing Cm and Tc. Cosmid DNA was purified and digested with PstI, and the resulting fragments were analyzed by gel electrophoresis. Hybrid cosmids of the resulting clones harbored several PstI fragments, including one which contains the mini-Tn5 and adjacent genomic DNA to the mini-Tn5 insertion locus. The cosmids were restricted with PstI, and obtained fragments were cloned into the unique PstI site of pBluescript SK−. Recombinant clones were selected on LB agar plates containing Ap and Cm. These recombinant plasmids were sequenced using the oligonucleotide M13 forward and reverse primers (Table 2), which hybridize specifically to pBluescript SK−. Based on the obtained sequences, primers were designed to map the entire region of the insertion site in the mutant of A. jadensis.

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotides used in this work as primers for PCR and to sequence recombinant plasmids

| Primer | Sequencea |

|---|---|

| I_end | GGCCGCACTTGTGTA TAAGAGTCAG |

| O_end | GCGGCCAGATCTGATCAAGAGACAG |

| M13-forward | GTAAAACGACGACGGCCGT |

| M13-reverse | CAGGAAACAGCTATGAC |

| 5′_algL | AAGGATCCGTGTTGGTTACCGGGTGTTCGCAAGC |

| 3′_algL | AAAAAGCTTTTACGGAGTCGCTTGCCACAATCCCG |

| 5′_algE | AAAAAGCTTGTGTCGCGATGTCTTTCTAATTCCGCCAG |

| 3′_algE | AAAAAGCTTTCACCACCTCCCTGCGACAACAAACAG |

| 5′_MATE | TTTTGGATCCAAGGAGAATATATGAGTGTGACCCTC |

| 3′_MATE | TTTTTAAGCTTTCATGCATGATGGCGACGTC |

| 5′_SmR | AAAAAGTCGACCTCACGCCCGGAGCGTAGCGACC |

| 3′_SmR | AAAAAGTCGACAACGACCCTGCCCTGAACCGACG |

Restriction sites used for cloning purposes are underlined.

Cloning of algE, algL, and MATE from A. borkumensis SK2.

The genes algE and algL were amplified from total genomic DNA of A. borkumensis SK2 by tailored PCR using the degenerated oligonucleotide pairs 5′_algE and 3′_algE or 5′_algL and 3′_algL (Table 2), respectively. The resulting PCR products were cloned as a HindIII fragment into the vector pET-19b or as a BamHI-HindIII fragment into cloning vector pUC19, yielding the plasmids pET-19b::algE and pUC19::algL, respectively. The gene MATE was amplified using the oligonucleotides 5′_MATE and 3′_MATE (Table 2), and the resulting PCR product was cloned as a HindIII-BamHI fragment into the vector pUC19, yielding plasmid pUC19::MATE.

Gene disruption by biparental filter mating technique.

For direct inactivation of the MATE, algE, and algL genes, an ΩSm cassette was amplified by PCR from the vector pCDF-Duet1 employing the primers 5′_SmR and 3′_SmR (Table 2) and cloned into the singular SalI site of algE or into the singular NcoI sites of algL and MATE, yielding plasmids pET19-b::algEΩSm, pUC19::algLΩSm, and pUC19::MATEΩSm, respectively. The resulting plasmids were then digested with HindIII (in the case of pUC19::algEΩSm) or BamHI-HindIII (in the case of pUC19::algLΩSm and pUC19::MATEΩSm) and fused to the HindIII or BamHI-HindIII-restricted mobilizable suicide plasmid pSUP202 (59), yielding plasmids pSUP202::algEΩSm, pSUP202::algLΩSm, and pSUP202::MATEΩSm, respectively. These plasmids were then transformed into E. coli S17-1.

Subsequently, inactivation of the algE, algL, and MATE genes in A. borkumensis SK2 was achieved by conjugational transfer of the suicide plasmid pSUP202::algEΩSm, pSUP202::algLΩSm, or pSUP202::MATEΩSm from E. coli strain S17-1 (donor) to A. borkumensis SK2 (recipient), employing the same biparental filter mating technique described above to generate mini-Tn5 transposon libraries using the appropriate antibiotics. Putative homozygous gene disruptant mutants resulting from homologous recombination with a double crossover event were identified by their Sm resistance and simultaneous Cm sensitivity.

DNA manipulation and molecular genetic methods.

DNA manipulations and other standard molecular biology techniques were performed as described previously (53). Plasmid DNA was isolated using the method described by Birnboim and Doly (9). Chromosomal DNA of Tn5-induced Alcanivorax mutants and wild types was isolated as described previously (38). Restriction enzymes and ligases were used according to the manufacturer's instructions.

DNA sequencing and sequence analysis.

DNA sequencing was performed by the chain termination method according to Sanger et al. (54) and with an ABI Prism 3730 capillary sequencer at the Universitätsklinikum Münster (UKM).

RESULTS

Occurrence, distribution, and composition of lipids accumulated in A. jadensis T9 and A. borkumensis SK2.

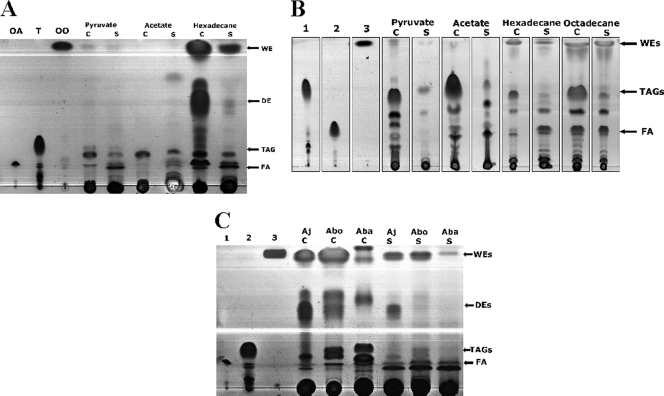

As demonstrated by TLC analysis, cells of Alcanivorax strains produce neutral lipids when cultivated in the presence of carbon sources, like pyruvate, acetate, hexadecane, and octadecane (Fig. 1 A and B). Biosynthesis of TAGs and WEs in both investigated Alcanivorax species was already detectable in the early exponential phase, but major amounts of both lipids were observed only in the stationary growth phase. In addition, accumulation of TAGs and WEs was promoted when the cells were cultivated under nitrogen-limited conditions (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

TLC analysis of storage lipid accumulation in A. jadensis T9, A. borkumensis SK2, and Acinetobacter baylyi strain ADP1. (A) Cells of A. jadensis T9 were cultivated in MWM medium containing 1% (wt/vol) sodium acetate, 1% (wt/vol) sodium pyruvate, or 0.3% (vol/vol) hexadecane. (B) Cells of A. borkumensis SK2 were cultivated in ONR7a medium containing 1% (wt/vol) sodium acetate, 1% (wt/vol) sodium pyruvate, 0.5% (vol/vol) hexadecane, or 0.5% (vol/vol) octadecane. Lanes: 1, triolein; 2, oleic acid; 3, oleyl oleate. (C) Cells of A. jadensis T9 and A. borkumensis SK2 were cultivated in MWM medium containing 0.3% (vol/vol) hexadecane, and cells of A. baylyi strain ADP1 were cultivated in MSM medium with 1% (wt/vol) sodium gluconate. Lanes: 1, oleic acid; 2, triolein; 3, oleyl oleate. After 72 h cultivation, when the cells were in the stationary growth phase, cells were harvested and lyophilized, and the lipids were extracted with chloroform-methanol (1:1 [vol/vol]). Lipids from supernatant samples were extracted directly from the culture broth with chloroform-methanol (1:1 [vol/vol]). Lipid extracts obtained from 5 mg lyophilized cells (C) or from the corresponding amount of supernatant (S) from cells grown on different carbon sources were applied per lane. The solvent system used for elution was hexane-diethyl ether-acetic acid (90:7.5:1 [vol/vol/vol] [panels A and C] and 80:20:1 [vol/vol/vol] [panel B]). Lipids were visualized by staining with iodine vapors. OA, oleic acid; T, triolein; OO, oleyl oleate; Aj, A. jadensis; Abo, A. borkumensis; Aba, A. baylyi; FA, free fatty acids.

(i) Lipids produced by A. jadensis strain T9.

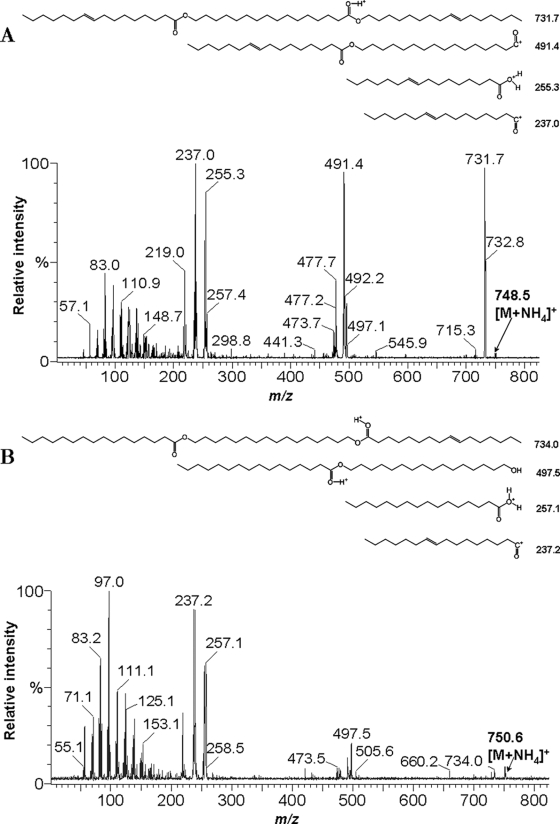

Occurrence of TAGs and WEs by A. jadensis T9 was analyzed using acetate, pyruvate, or hexadecane as the sole carbon and energy source. TLC analysis of the lipids in A. jadensis T9 after cultivation on different carbon sources is shown in Fig. 1A. In cells of A. jadensis T9 grown in MWM medium with hexadecane as the sole carbon source, the presence of WEs and small quantities of TAGs could be observed. Besides TAGs and WEs, the presence of other substances was also observed. Mass spectrometry analysis (as described below) identified these substances as DEs (Fig. 2). In addition, several other lipophilic substances of unknown chemical composition were observed. However, they were present only in trace amounts, and they were therefore not analyzed further. TAGs and WEs were present only in small amounts when pyruvate or acetate was used as the sole carbon source.

FIG. 2.

ESI/MS2 spectra of wax diesters isolated from A. jadensis T9. Wax diesters were isolated by preparative TLC prepared from extracts of cells cultivated in MWM medium containing 0.3% (vol/vol) hexadecane as the sole carbon source. Extracts obtained from 3 mg cells (A) (intracellular) and the corresponding amount of supernatants (B) (extracellular) were analyzed. The observed fragmentation is compatible with a C16 fatty acid combined with a C16 hydroxy fatty acid and a C16-ol containing two double bonds (panel A) and C16-diol esterified with hexadecanoic and hexadecenoic acid (panel B). The position of the double bond was arbitrarily chosen.

WEs and DEs produced by A. jadensis T9 exhibited different chemical compositions, depending if they were present inside or outside of the cells. Doubly unsaturated forms of WEs and DEs were predominantly intracellular, while the secreted ones were mostly monounsaturated. For identification of the intra- and extracellular DEs produced by A. jadensis T9, lipid extracts from cells and supernatants were isolated from preparative TLC plates and subjected to analysis by ESI/MS2. The evaluation of ESI-MS spectra and fragmentation patterns revealed that A. jadensis T9 produced DEs with molecular weights of 730.7 (mainly inside the cells) and 732.7 (outside). These molecules appear as pseudomolecular ions at 748.6 (Fig. 2A) and 750.6 (Fig. 2B) by the addition of NH4+ cations. The MS2 of these ions revealed the presence of C16 fatty acids combined either with a hydroxy C16 acid and a C16-ol or with a C16-diol with a second C16 acid.

While secretion of neutral lipids into cell-free culture supernatants occurred under all experimental conditions, the rate of lipid export was low in cells grown on acetate or pyruvate as the sole carbon source. In contrast to that, cells of A. jadensis T9 synthesized and exported substantial amounts of WEs in the presence of hexadecane as the sole carbon source. Figure 1A shows that even DEs were produced and excreted, although in much smaller amounts than those of WEs. Mass spectrometry analysis revealed that WEs and DEs produced by A. jadensis T9 consisted mainly of compounds comprising a C16 chain length as mentioned above.

(ii) Lipids produced by A. borkumensis strain SK2.

Production of neutral lipids by A. borkumensis SK2 was analyzed with cells cultivated in the presence of acetate, pyruvate, hexadecane, or octadecane as the sole carbon source (Fig. 1B). Lipid characterization was performed by preparative TLC and subsequent GC analysis. Large amounts of TAGs were accumulated in the cells if they were grown on pyruvate or acetate, whereas WEs were barely synthesized. When cells were cultivated with pyruvate or acetate, TAGs consisted of almost the same proportion of saturated and unsaturated fatty acids (data not shown). However, when the cells were cultivated with alkanes, such as hexadecane or octadecane, WEs in combination with TAGs were produced. In this case, WEs consisted almost exclusively of saturated fatty acids (palmitic acid, C16:0; and stearic acid, C18:0), with only a small proportion of unsaturated fatty acids (data not shown). Cells cultivated with pyruvate or acetate showed better growth than cells cultivated with hexadecane or octadecane. The production of neutral lipids was proportionally higher when cells were cultivated with pyruvate or acetate.

In cells of A. borkumensis SK2 grown with pyruvate as the sole carbon source, the export of TAGs seemed to be predominant, whereas only a trace amount of WEs was observed by TLC analysis (Fig. 1B). In contrast, when alkanes were used as the sole carbon source, the presence of WEs and TAGs was also observed, and it seemed that WEs were exported preferentially as revealed by TLC analysis. Likewise, a predominance of WEs in comparison to TAGs in supernatant samples was observed when A. borkumensis SK2 was cultivated with alkanes from C11 to C18 (data not shown).

In contrast to the two Alcanivorax strains, cells of A. baylyi strain ADP1 accumulated TAGs and WEs exclusively intracellularly as insoluble inclusions under growth-limiting conditions. Cells of this bacterium secreted only trace amounts of WEs and none of the other lipids (DEs or TAGs) (Fig. 1C). Therefore, the ability to export neutral lipids seems to be characteristic of Alcanivorax strains when they are cultivated on alkanes, like hexadecane or octadecane.

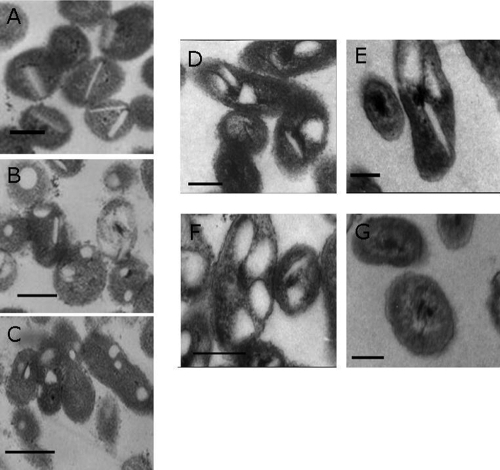

Ultrastructure of intracellular storage lipid inclusions in Alcanivorax species.

The accumulation of lipophilic substances in bacteria is normally accompanied by morphological changes of the cells. To observe whether synthesis of lipids by Alcanivorax provokes changes of the cell morphology, we have conducted experiments with both Alcanivorax species grown in the presence of hexadecane. The morphology of cells growing in the exponential or stationary phase was analyzed by TEM (Fig. 3A to G). Lipid inclusions in both Alcanivorax strains showed extreme heterogeneity in shape and size, comprising spherical, rectangular, disc-shaped, and irregularly shaped inclusions. In cells of A. borkumensis SK2 in the early exponential phase, a predominance of disc-shaped inclusions was detected, while at the end of the exponential phase only a few of these inclusions were recognized (Fig. 3A and B). Moreover, in the stationary growth phase almost all inclusions showed a spherical or irregular form, and disc-shaped inclusions were very rare (Fig. 3C). Concerning the number of inclusions, no significant differences between cells of both growth phases were detected. However, the cell form changed slightly, as was obvious from the TEM. Whereas cells in the early exponential phase exhibited mainly a circular form, the cells became more elongated in the stationary phase.

FIG. 3.

Structure of neutral lipid inclusions in A. borkumensis SK2 and A. jadensis T9. Cells of A. borkumensis SK2 were cultivated in ONR7a medium containing 0.5% (vol/vol) hexadecane. Cells of A. jadensis T9 were cultivated in MWM medium containing 0.3% (vol/vol) hexadecane. Ultrathin sections of cells were analyzed by TEM as reported previously (44). Samples were taken after 12 h (early exponential growth phase), 48 h (late exponential growth phase), and 96 h (stationary growth phase) for A. borkumensis SK2 and after 32 h (exponential growth phase) and 60 h and 72 h (stationary growth phase) for A. jadensis T9. The scale bars correspond to 200 nm. Cells of A. borkumensis SK2 after 12 h (A), 48 h (B), or 96 h (C) and A. jadensis T9 after 32 h (D), 60 h (E), and 72 h (F) of growth are shown. Cells of A. jadensis T9 after 60 h without lipid inclusions were observed (G).

In the case of A. jadensis, the forms of the lipid inclusions in the cells were also highly heterogeneous (Fig. 3D to F). Also, here disc-shaped, spherical, half-moon-like, and irregular forms of inclusions were found in the exponential (Fig. 3D) as well as in the stationary growth phase (Fig. 3E and F). Slight differences in cell form and size were detected. The number of lipid inclusions in the cells remained almost constant. However, it must be emphasized that the presence of lipid inclusions was not uniform between the cells and that cells with few or without inclusions were also detected (Fig. 3G).

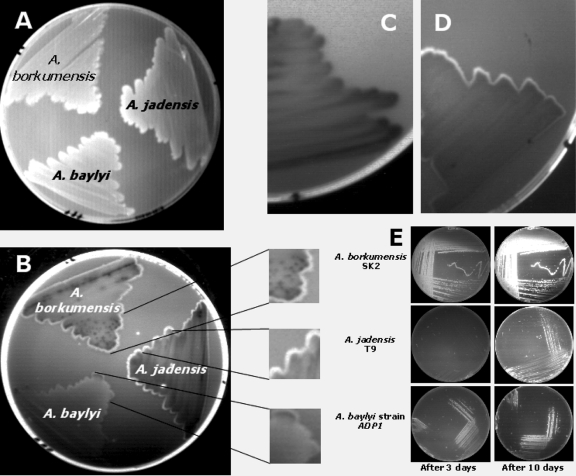

Screening of lipid-negative mutants using Nile Red and the lipophilic stain Solvent Blue 38.

Unraveling a lipid export mechanism in Alcanivorax strains requires a quick method allowing convenient identification and fast selection of mutants defective in lipid biosynthesis and/or export and also to discriminate between these two events. Therefore, the feasibility of using different stains, like NR or SB38, was investigated. These stains were used in the past to investigate processes involving lipophilic substances (15, 34, 37, 39, 62). NR produces a strong fluorescence with an excitation maximum at a wavelength of 543 nm upon binding to PHB granules in cells of Ralstonia eutropha (15). In addition to the two strains of Alcanivorax spp., A. baylyi strain ADP1 was employed as a lipid secretion-negative strain for comparison in our experiments.

With the use of NR and SB38, the appearance of a border surrounding the surface of cells of A. baylyi strain ADP1, A. borkumensis SK2, and A. jadensis T9 growing on agar plates with hexadecane as the sole carbon source (Fig. 4A) was noticed. In plates containing SB38, the cells acquired a slightly blue border, being more evident in the case of A. borkumensis SK2 than in the case of A. jadensis T9 or A. baylyi strain ADP1. After addition of NR to plates containing SB38 and incubation of these for 6 to 7 days, the appearance of a whitish border surrounding the cell colonies, which exhibited fluorescence in the presence of UV light, was detected. After incubation of the plates with additional NR solution (1 mg/liter) for 30 min, an increase of the fluorescence at the border surrounding the cells was observed (Fig. 4B).

FIG. 4.

Fluorescence analysis of A. jadensis T9, A. borkumensis SK2, and A. baylyi strain ADP1 streaks grown on plates with hexadecane as the sole carbon source. A. jadensis T9, A. borkumensis SK2, and A. baylyi strain ADP1 were plated on MWM plates with Nile red and Solvent Blue 38 and incubated at 30°C with hexadecane vapor as the carbon source. After 6 or 7 days of incubation, a whitish border surrounding the edge of the colonies became evident (A), and this border showed a stronger fluorescence after an additional treatment with a Nile red solution (B). The fluorescent border was less evident in cells of A. jadensis T9 grown on MWM plates with Nile red and Solvent Blue 38 containing pyruvate (C) than in cells grown with hexadecane as the sole carbon source (D). The fluorescence of these strains grown on ONR7a plates with hexadecane was already evident after 3 days incubation, but it was stronger after 10 days of incubation (E).

As A. jadensis T9 produced only minor amounts of neutral lipids when it was cultivated with pyruvate as the sole carbon source, the fluorescence under UV light of cells growing on MWM plates with pyruvate (Fig. 4C) or hexadecane (Fig. 4D) as the sole carbon source was also analyzed. Cells growing on plates containing hexadecane showed higher fluorescence than cells growing on pyruvate, which is in concordance with our observations regarding the production of lipids by A. jadensis as described above (compare Fig. 1A with Fig. 4C and D). In addition, the presence of a border was more evident in cells growing on hexadecane than in cells growing on pyruvate, which could be related to the export of neutral lipids by A. jadensis.

We also studied the development of fluorescence intensity in relation to the time course of incubation. Cells of A. borkumensis SK2, A. jadensis T9, and A. baylyi strain ADP1 were cultivated on ONR7a plates with NR for 10 days at 30°C, and the fluorescence was analyzed after 3 days and 10 days incubation (Fig. 4E). Whereas cells of A. borkumensis SK2 showed strong fluorescence already after 3 days of incubation, cells of A. jadensis T9 and A. baylyi strain ADP1 showed only a weak fluorescence. This tendency had not changed very much after 10 days of incubation. Therefore, differences in lipid biosynthesis were already detectable after a few days of cultivation.

These results demonstrated that a combination of NR and SB38 may be used to detect mutants defective in lipid biosynthesis and export. The observation that cells of A. jadensis showed a border surrounding the streaks and that this border could be related to the amount of lipid produced and/or exported by the cells led to the decision to use agar plates containing NR alone, NR plus SB38, or SB38 alone to identify and select mutants with defects in lipid biosynthesis and/or export. A random mini-Tn5 transposon mutagenesis strategy was employed to induce mutations in Alcanivorax yielding phenotypes indicating defects in lipid biosynthesis. About 5,000 mutants of A. borkumensis and 4,000 mutants of A. jadensis were analyzed and screened. Mutants with lower fluorescence or phenotypical changes under UV light were selected and studied further. The use of lipophilic stains, such as NR and SB38, allowed the rapid identification and selection of transconjugants showing defects in lipid metabolism.

Mutants defective in lipid export.

Based on the screening method described above, three transconjugants of A. jadensis (Aj5, Aj7, and Aj17) and seven transconjugants of A. borkumensis (ABO_6/39, ABO_10/30, ABO_19/48, ABO_25/21, ABO_26/1, ABO_27/29, and ABO_27/56) were isolated. These transconjugants showed reduced fluorescence under UV light or were phenotypically different in terms of the border surrounding the streaks compared to the wild-type strain. They were therefore analyzed for their capability to synthesize and export lipids.

The lipids of the three mutants of A. jadensis were analyzed. Mutants Aj7 and Aj17 were no longer able to export DEs and WEs (Fig. 5A) but still accumulated these lipids intracellularly. In contrast, mutant Aj5 showed a drastic reduction of intracellular lipid biosynthesis and was not further investigated. TLC analysis of the intra- and extracellular lipids by all seven mutants of A. borkumensis revealed that they were all no longer able to export TAGs growing on pyruvate as the sole carbon source. For simplicity, TLC analysis of only three mutants is presented in Fig. 5B, because all seven mutants showed the same phenotype. Moreover, transconjugants ABO_10/30 and ABO_19/48 showed insertions in the same gene (see below). However, all seven mutants accumulated lipids intracellularly. These mutants with incapacities to export TAGs were then genotypically characterized.

FIG. 5.

TLC analysis of A. jadensis T9 and A. borkumensis SK2 mini-Tn5 induced mutants with defects in lipid export. (A) Cells of A. jadensis T9 and of the mutants were cultivated in MWM medium containing 0.3% (vol/vol) hexadecane for 72 h, harvested, and lyophilized, and the lipids were extracted with chloroform-methanol (1:1 [vol/vol]). The lipids from supernatant samples were extracted directly from culture broth with chloroform-methanol (1:1 [vol/vol]). Lipid extracts obtained from 5 mg lyophilized cells (C) and the corresponding amount of supernatant (S) were applied per lane. The solvent system hexane-diethyl ether-acetic acid (90:7.5:1 [vol/vol/vol]) was used for elution, and lipids were visualized by staining with iodine vapor. Lanes: 1, oleic acid; 2, triolein; 3, oleyl oleate. Wild type (WT), A. jadensis T9; 5, 7, and 17 denote the three mutants isolated from this strain. (B) Cells of A. borkumensis SK2 and mutants were cultivated in ONR7a medium containing 1% (wt/vol) sodium pyruvate for 72 h, harvested, and lyophilized, and the lipids were extracted with chloroform-methanol (1:1 [vol/vol]). The lipids from supernatant samples were extracted directly from the culture broth with chloroform-methanol (1:1 [vol/vol]). Lipid extracts obtained from 5 mg lyophilized cells (C) and from the corresponding amount of supernatant (S) were applied per lane. The solvent system hexane-diethyl ether-acetic acid (80:20:1 [vol/vol/vol]) was used for elution, and lipids were visualized by staining with iodine vapor. Lanes: T, triolein; OA, oleic acid; OO, oleyl oleate. Wild type (WT), A. borkumensis SK2; ABO denotes different transposon-induced mutants, and algL, algE, and MATE denote the corresponding constructed knockout mutants.

Mapping of transposon insertions.

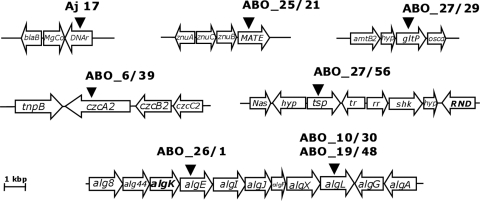

The transposon library generated with A. borkumensis represented approximately twofold genome coverage, and since in some cases we detected mutants in which identical genes were disrupted, the library can be considered widely saturated. After confirmation of transposon insertions by Southern blot hybridization, the insertions were mapped as described in Materials and Methods. The genotypic characterization of all mutants, including the identification of the genes disrupted by the mini-Tn5 insertion, is summarized in Table 3. The insertion sites and the adjacent regions are shown in Fig. 6. The sequences were blasted against the A. borkumensis genome (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) by searching the protein database using the translated nucleotide query (Blast) (3).

TABLE 3.

Genotypic characterization of mini-Tn5-induced mutants of Alcanivorax strains defective in lipid export

| Mutanta | Phenotype | Insertion locus of mini-Tn5 (gene product) | Amino acid identity (%) (strain) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aj5 | Negative in DE export | (Transposase putative) | 68 (Alcanivorax borkumensis) |

| Aj7 | Negative in DE export | mgtE (transport of magnesium) | 85 (Alcanivorax borkumensis SK2) |

| Aj17 | Negative in DE export | DNAr (possibly reparation of alkylated DNA) | 71 (Alcanivorax borkumensis SK2) |

| ABO_6/39 | Negative in TAG export | czcA2 (heavy metal RND efflux transporter) | 100 (A. borkumensis SK2) |

| ABO_10/30 ABO_19/48 | Negative in TAG export | algL (alginate lyase) | 100 (A. borkumensis SK2) |

| ABO_25/21 | Negative in TAG export | MATE (MATE efflux family protein) | 100 (A. borkumensis SK2) |

| ABO_26/1 | Negative in TAG export | algE (alginate outer membrane protein) | 100 (A. borkumensis SK2) |

| ABO_27/29 | Negative in TAG export | gltP (sodium dicarboxylate symporter family protein) | 100 (A. borkumensis SK2) |

| ABO_27/56 | Negative in TAG export | tsp (two-component sensor protein) | 100 (A. borkumensis SK2) |

Aj denotes A. jadensis T9; ABO denotes A. borkumensis SK2.

FIG. 6.

Gene organization of the loci identified by mini-Tn5 mutagenesis of Alcanivorax strains. The diagram shows the localization of mini-Tn5 insertions in the mutants of A. jadensis T9 (Aj17) and of A. borkumensis SK2 (ABO) showing a defect in lipid export. The positions of mini-Tn5 insertions in the respective mutants (see Table 3 for designations) are indicated by triangles. Lengths and directions of arrows show the genes and directions of transcription of the respective genes. For Aj17, putative identities of the gene products suggested by amino acid sequence identities to protein in the GenBank database are as follows: blaB, metallo-beta-lactamase family protein; MgCo, CorA family magnesium/cobalt transporter; DNAr, possibly reparation of alkylated DNA. For A. borkumensis, the gene products are tnpB, transposon B protein; czcA2, heavy metal RND efflux transporter, CzcA family; czcB2, heavy metal RND efflux membrane fusion protein, CzcB family; and czcC2, heavy metal RND efflux outer membrane protein, CzcC family (mutant ABO_6/39). alg8, alginate biosynthesis protein alg8; alg44, alginate biosynthesis protein Alg44; algK, alginate biosynthesis regulator; algE, outer membrane alginate export protein; algI, alginate O-acetylation protein AlgI; algJ, alginate O-acetylation protein AlgJ; algF, alginate O-acetyltransferase; algX, alginate biosynthesis protein AlgX; algL, alginate lyase; algG, poly(beta-d-mannuronate) C5 epimerase precursor; algA, mannose 6-phosphate isomerase/mannose 1 phosphatase (mutants ABO_10/30; ABO_19/48 and ABO_26/1). znuA, high affinity zinc uptake system protein znuA precursor; znuC, zinc transport protein, ATPase; znuB, zinc ABC transporter permease protein; MATE, MATE efflux family protein putative (mutant ABO_25/21). amtB2, ammonium transporter, putative; hyp, hypothetical protein; gltP, sodium dicarboxylate symporter family protein; oscd, oxidoreductase, short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase family (mutant ABO_27/29). Nas, Na+ symporter family protein; hyp, hypothetical protein; tsp, two-component sensor protein; tr, transcription regulator, putative; rr, response regulator; shk, sensor histidine kinase; RND, probable RND efflux transporter (mutant ABO_27/56).

Mapping of the mini-Tn5 insertion in the mutant Aj17 of A. jadensis revealed disruption of a gene which putatively encodes a DNA repair system specific for alkylated DNA exhibiting 61% identical amino acids to the homologous gene of A. borkumensis SK2. In addition, a magnesium transporter homologue was mapped in the genome of the mutant Aj7. The Mg transporter belongs to a group of ion transporters that mediate the transport of divalent metal ions across biological membranes. Their functions have been investigated with E. coli and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium LT2 (28).

Mutant 6/39 from A. borkumensis (ABO_6/39) was unable to export TAGs using pyruvate as the sole carbon source. The mini-Tn5 insertion was localized in the gene czcA2, which codes for a heavy metal resistance, nodulation, and division (RND) family efflux protein. The RND protein family was first described as comprising a related group of bacterial transport proteins involved in heavy metal resistance (Ralstonia metallidurans), nodulation (Mesorhizobium loti), and cell division (E. coli) (52, 63). This protein belongs to a three-component Czc (Cd2+, Zn2+, and Co2+) chemiosmotic efflux pump of soil microorganisms (40). This efflux pump consists of inner membrane (CzcA2), outer membrane (CzcC), and membrane-spanning (CzcB) proteins, which together transport cations from the cytoplasm across the periplasmic space to the outside of the cell (58). The CzcABC complex is an efflux pump that functions as a chemiosmotic divalent cation/proton antiporter (41).

Mapping of the mini-Tn5 insertion of two A. borkumensis mutants (ABO_10/30 and ABO_19/48) revealed disruption of the algL gene. algL codes for a gene product showing similarity to an alginate lyase (AlgL) and belongs to a cluster of genes in the chromosome of A. borkumensis that are presumably involved in alginate production. Alginate biosynthesis is a well-characterized process in species of Pseudomonas and Azotobacter. Both genera produce alginate as exopolymeric polysaccharide during their vegetative growth (48). Alginate plays a key role as a virulence factor of plant-pathogenic pseudomonads in the formation of biofilms and with the encystment process of Azotobacter spp. (22). AlgL is a periplasmic protein that catalyzes the degradation of alginate via β-elimination (2). Alginate lyases have been isolated from a variety of marine bacteria, soil bacteria, and fungi, and in some cases, such as for certain Pseudomonas spp., the presence of more than one alginate lyase has been reported (67). The function of AlgL is not clear. It is possible that AlgL is part of a polymerization complex within the periplasm, assembling the alginate exopolysaccharide for transport to the cell surface (67). It may also function as an editing protein to control the length of the polymer (10), or it may serve the polymerase with alginate oligomers to prime synthesis (45). For the latter, AlgL could be involved in the modification of oligomers and therefore in the process to export the polymer to the cell surface. Although it has been reported that mutants defective in AlgL appeared nonmucoid and produce only small amounts of alginate (48, 67), AlgL is essentially required for alginate biosynthesis (2). It has also been reported that Ca2+ and Mn2+ can selectively activate or inhibit alginate lyase and epimerization activity in algae (35).

In the genome of the A. borkumensis mutant ABO_26/1, the insertion was mapped in a gene coding for an outer membrane alginate export protein (algE), which belongs to the same gene cluster as algL. In Pseudomonas aeruginosa, the expression of AlgE is strictly correlated with the mucoid phenotype of the strain (25, 46). Biochemical and electrophysiological studies of AlgE revealed that it forms an anion-selective pore in the outer membrane (47). In lipid bilayer experiments, it has been observed that GDP-mannuronic acid could partially block this pore. Moreover, according to the model of Rehm and coworkers (47), AlgE is a β-barrel protein consisting of 18 β-strands. These data are consistent with the hypothesis that AlgE forms an alginate-specific pore that enables export of the nascent alginate chain through the outer membrane (48). Thus, AlgL and AlgE may be involved in the export of the nascent polymer.

A disruption of a gene putatively coding for a multidrug and toxic compound extrusion (MATE) efflux protein was identified with the A. borkumensis mutant ABO_25/21. The adjacent region contains a zinc ABC-transport uptake system. These proteins were described as a new group of proteins, representing a family of transport proteins responsible for protecting cells from drugs and other toxic compounds (12). Proteins belonging to the MATE family occur ubiquitously in all three domains of life (30). Some proteins of this family have been shown to function by a drug/Na+ antiport mechanism, but for most of the other members of this family the function is unknown (30).

Mapping of the mini-Tn5 insertion in the genome of the A. borkumensis mutant ABO_27/29 revealed the disruption of a gene coding for a two-component sensor protein (tsp), which are typically composed of an amino-terminal sensor and a carboxy-terminal transmitter domain containing a kinase activity, catalyzing the autophosphorylation of a histidine residue (8).

Mapping of the mini-Tn5 insertion in the genome of the A. borkumensis mutant ABO_27/56 revealed a Na+ symporter family protein and an RND efflux transporter adjacent to the site of mini-Tn5 insertion (Fig. 6). It is not certain in which way the disruption of tsp might have influenced the function of the adjacent genes.

A disruption in the genome of the A. borkumensis mutant ABO_27/29 was localized in a gene encoding a sodium dicarboxylate symporter family. This gene is localized in a region coding for an ammonium transport system, which is only one of three high-affinity ammonium transporter systems present in the genome of A. borkumensis SK2 (57).

To confirm the phenotype of the transconjugants defective in lipid export, the genes algL (mutants ABO_10/30 and ABO_19/48), algE (transconjugant ABO_26/1), and MATE (transconjugant ABO_25/21) were also disrupted by insertion of an Sm resistance gene cassette. The absence of neutral lipids in supernatant samples was corroborated through GC analysis, showing that transconjugants and their corresponding site-directed knockout mutants were able to synthesize and accumulate lipids intracellularly but were no longer able to export them (Table 4). A. borkumensis SK2 grew to a cell density of about 0.8 g/liter, intracellularly accumulating TAGs that were about 5% of its cell dry weight (CDW) when cultivated with pyruvate as the sole carbon source. The transconjugants ABO_26/1 and ABO_19/48 grew to cell densities of 0.5 and 0.6 g/liter, with intracellular lipid contents between 2.75 and 4.56%, respectively, while transconjugant ABO_25/21 grew to a cell density of 0.7 g/liter and accumulated 4.89% of lipids. The corresponding knockout mutants showed growth to cell densities of 0.7 (ΔalgE mutant) and 0.6 (ΔalgL and ΔMATE mutants) g/liter, with intracellular lipid contents of 3.56, 4.87, and 3.78%, respectively. No significant presence of extracellular TAGs was observed in culture supernatants of either transconjugants or knockout mutants. Only in the case of the ΔalgE mutant, about 0.025 mg of the extracellular fatty acids were observed, representing about 13% of the value determined for A. borkumensis SK2.

TABLE 4.

Growth and fatty acid content of A. borkumensis SK2 mini-Tn5-induced mutants and knockout mutants defective in lipid export growing on pyruvate as sole carbon source

| Strain | Cell density (CDW [mg/ml])a | Total fatty acids (% of CDW)b | Fatty acid content (total mg)c |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intracellular | Extracellular | |||

| SK2 | 0.8 ± 0.038 | 5.57 | 0.56 | 0.19 |

| ABO_19/48 | 0.6 ± 0.012 | 4.56 | 0.45 | ND |

| ΔalgL strain | 0.6 ± 0.012 | 4.87 | 0.48 | ND |

| ABO_25/21 | 0.7 ± 0.056 | 4.89 | 0.48 | ND |

| ΔMATE strain | 0.6 ± 0.016 | 3.78 | 0.37 | ND |

| ABO_26/21 | 0.5 ± 0.163 | 2.75 | 0.27 | ND |

| ΔalgE strain | 0.7 ± 0.001 | 3.56 | 0.35 | 0.025 |

CDW, cell dry weight.

Lipid extracts were obtained from 10 mg cells (see text for details). The values correspond to the average of two independent determinations.

Fatty acid content represents the amounts deter mined in samples of intra- and extracellular extracts. Total amounts were determined from 10 mg dry cells or the corresponding amounts in the supernatants. Values are average values resulting from two independent determinations. ND, not detected.

DISCUSSION

Biosynthesis of neutral lipids, such as TAGs and WEs, is promoted if an essential nutrient is limiting growth and if a carbon source is present in excess at the same time (66). For marine oil-degrading bacteria, such as those belonging to the genus Alcanivorax, oil spills constitute a temporary condition of carbon excess coupled with limited nitrogen availability (high carbon-nitrogen ratio [C/N]), which triggers the production of storage compounds in bacteria (51). When A. jadensis T9 was cultivated in MWM medium, which contains tryptone and yeast extract, intracellular and extracellular synthesis of TAGs and WEs was already observed in the early exponential growth phase. However, the accumulation of TAGs and WEs together with DEs was increased in the stationary growth phase. Only a small amount of TAG but no WE or DE synthesis was observed under the conditions studied when cells were cultivated with pyruvate or acetate as the sole carbon source. To the contrary, both WEs and DEs were observed during cultivation on hexadecane, suggesting that A. jadensis T9 synthesizes fatty acids from the oxidation of alkanes. A. borkumensis SK2 produces mainly TAGs during cultivation in the presence of pyruvate or acetate, while WEs were synthesized during cultivation on alkanes, such as hexadecane and octadecane. In addition, in A. borkumensis the production of neutral lipids was increased in the stationary growth phase. Although ONR7a medium contains only relatively little nitrogen (C/N of about 50 if 1% pyruvate is used as the sole carbon source), an increase in neutral lipid accumulation could be related to the depletion of nitrogen at the end of the cultivation period. As it was pointed out above, the production of extracellular neutral lipids seems to be a characteristic of Alcanivorax strains and does not occur in A. baylyi strain ADP1. Based on the export of lipids by Alcanivorax strains, a screening method was developed to select transconjugants defective in biosynthesis or export of neutral lipids. Although with the use of NR and SB38 it was not possible to discriminate between different types of exported lipids, this method constituted a first screening step to support the identification of the genes responsible for the export of neutral lipids.

Although the production of extracellular lipids has previously been reported for other bacteria, such as Acinetobacter sp. (60), Alcaligenes sp. PHY9, and Pseudomonas nautica strain 617 (24), and for the fungus Cladosporium resinae (61), the function of lipid export is unclear. As a part of surface-active compounds (also known as biosurfactants or bioemulsifiers), specialized lipids with a chemical structure different than those investigated in this study could play a role in the modification of medium properties and could therefore enhance the contact between bacteria and water-insoluble hydrocarbons. Hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria produce biosurfactants of diverse chemical natures and molecular sizes (49). These surfactants disperse hydrophobic compounds, thereby increasing their surface to enhance growth of cells. Lipid moieties are present not only in low-molecular- but also in high-molecular-weight biosurfactants in the form of glycolipids, lipoproteins, or lipopolysaccharides (36, 49). The export mechanism of lipids by Alcanivorax strains remains unclear to date. It has been proposed that the glycolipids of A. borkumensis SK2 might be precursors of a biosurfactant or could play a role in the function of the outer cell membrane (1). Species such as P. aeruginosa or Acinetobacter RAG-1 can use their biosurfactants to regulate their cell surface properties (49). Therefore, the production and export of lipids by Alcanivorax may constitute a step in the synthesis of biosurfactants to increase the availability of hydrophobic substances, hence improving the probability of survival in habitats with the presence of hydrophobic compounds.

The accumulation of neutral lipids was accompanied by changes in cell morphology. Alcanivorax strains form different types of lipid inclusions at different stages of growth, which is also related to slightly morphological changes of the cells. Changes in buoyant density were previously described for cells accumulating PHAs (44).

The occurrence of lipids as storage compounds seems to be frequent in marine bacteria (5) and may provide a selective advantage for their survival in environments with fluctuating conditions (65). However, little information exists about a clear function of these compounds in marine bacteria of the genus Alcanivorax. No differences in the survivals of cells could be observed between A. borkumensis SK2 and a knockout mutant with reduced storage lipid accumulation (32). Apparently, the lipids produced by A. borkumensis SK2 do not provide an advantage in survival, even after a prolonged starvation period.

Why and how cells of Alcanivorax species export neutral lipids is unknown. Therefore, it is possible that the export mechanism constitutes a new system of compound expulsion in bacteria. During screening of mutants defective in lipid accumulation and/or export, different mutants with disruption in genes encoding proteins involved in various transport processes were isolated. However, it must also be considered that genome annotations can contain mistakes, and although sequence similarities were high, sometimes the proposed function does not match the true enzymatic activity of the gene product. Gram-negative bacteria have evolved transport mechanisms that export macromolecules of toxic compounds across the two membranes of cell envelope in a simple energy-coupled step (43). The process requires (i) a cytoplasmic membrane export system, (ii) a membrane fusion protein (MFP), and (iii) an outer membrane cofactor (OMF) (43). Five families of proteins are recognized as membrane export systems: (i) ATP binding cassette (ABC) transporters, (ii) the major facilitator super family (MFS) transporters, (iii) RND transporters, (iv) small multidrug resistance (SMR) systems, and (v) MATE systems (55). Members of at least three types of transports systems, the ABC-type, RND-type, and MFS-type transporters, have been proposed to function together with MFP to facilitate transport across both membranes of the cell envelope of gram-negative bacteria (18, 20, 42, 52). In addition, it was proposed that some of these systems function in combination with OMF (17, 18, 20). A structural model depicting a possible arrangement of MFP and OMF in association with the cytoplasmic membrane permease in the bacteria cell envelope has been proposed (43). The A. borkumensis SK2 genome codes for a broad range of transport proteins (57). These comprise about 50 permeases; roughly half of them belong to high-affinity ABC transporter systems, five are major facilitator superfamily transport systems, and two are tripartite ATP-independent periplasmic (TRAP) C4-dicarboxylate transporters. Interestingly, no ABC-like transporters for carbohydrates were found (57). In this study, it was observed that the export of lipids was diminished or totally impeded if one of the algE, algL, and MATE genes, which encode transport proteins, was disrupted by a mini-Tn5 transposon. The same phenotype was observed with the constructed knockout mutants, in which the presence of extracellular lipids was partially or totally impeded (Table 4). According to the results presented here, it can be hypothesized that the export of neutral lipids in Alcanivorax is probably an unspecific mechanism. The disruption of a gene involved in the general transport of macromolecules across the cell membrane seems to provoke the interruption of lipid export as well, causing the intracellular accumulation of these lipids.

Biosynthesis of TAGs and WEs in bacteria is a process localized at the cytoplasm (64). Insertions in mutants of Alcanivorax were identified with genes encoding proteins involved in different transport processes localized in the membrane. Although the mechanism responsible for lipid export in Alcanivorax remains unclear, it may be possible that the disruption of these genes causes an inhibition of lipid export, and therefore, the accumulation of neutral lipids occurs only intracellularly. Further investigations are necessary to elucidate the export mechanism for neutral lipids in Alcanivorax strains. At present, the influence of some transport proteins on the export of neutral lipids is being investigated in our laboratory.

While the mutations identified in this study do not allow the establishment of a conclusive mechanism for lipid export at this time, this is the first report of the identification of the genetic determinants involved herein, which represents an important step forward toward understanding this process.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant provided by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft to A.S. (Ste386/7-3). E. Manilla-Pérez gratefully received a fellowship from the National Council on Science and Technology (CONACyT, Mexico) and the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD).

E.M.P. thanks K. Kampmann, S. Uthoff, J. H. Wübbeler, and D. Bröker for helpful discussions. We thank H. Luftmann (Institut für Organische Chemie, Universität Münster) for ESI/MS2 analysis.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 20 November 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abraham, W.-R., H. Meyer, and M. Yakimov. 1998. Novel glycine containing glucolipids from the alkane using bacterium Alcanivorax borkumensis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1393:57-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Albrecht, M. T., and N. L. Schiller. 2005. Alginate lyase (AlgL) activity is required for alginate biosynthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 187:3869-3872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Altschul, S. F., T. L. Madden, A. A. Schäffer, J. Zhang, Z. Zhang, W. Miller, and D. J. Lipman. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alvarez, H. M., F. Mayer, D. Fabritius, and A. Steinbüchel. 1996. Formation of intracytoplasmic lipid inclusions by Rhodococcus opacus strain PD630. Arch. Microbiol. 165:377-386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alvarez, H. M., O. H. Pucci, and A. Steinbüchel. 1997. Lipid storage compounds in marine bacteria. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 47:132-139. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arabolaza, A., E. Rodriguez, S. Altabe, H. Alvarez, and H. Gramajo. 2008. Multiple pathways for triaclyglycerol biosynthesis in Streptomyces coelicolor. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:2573-2582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bachmann, B. J. 1987. Linkage map of Escherichia coli K12, p. 807-876. In F. C. Neidhardt, J. L. Ingraham, K. B. Low, B. Magasanik, M. Schaechter, and H. E. Umbarger (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium: cellular and molecular biology, vol. 2. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beier, D., B. Schwarz, T. M. Fuchs, and R. Gross. 1995. In vivo characterization of the unorthodox BvgS two-component sensor protein of Bordetella pertussis. J. Mol. Biol. 248:596-610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Birnboim, H. C., and J. Doly. 1979. A rapid alkaline extraction procedure for screening recombinant plasmid DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 7:1513-1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boyd, A., M. Gosh, T. B. May, D. Shinabarger, R. Keogh, and A. M. Chakrabarty. 1993. Sequence of the algL gene of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and purification of its alginate lyase product. Gene 131:1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bredemeier, R., R. Hulsch, J. O. Metzger, and L. Berthe-Corti. 2003. Submersed culture production of extracellular wax esters by the marine bacteria Fundibacter jadensis. Mar. Biotechnol. 5:579-583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown, M. H., I. T. Paulsen, and R. A. Skurray. 1998. The multidrug efflux protein NorM is a prototype of a new family of transporters. Mol. Microbiol. 31:394-395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bruns, A., and L. Berthe-Corti. 1999. Fundibacter jadensis gen. nov., sp. nov., a new slightly halophilic bacterium, isolated from intertidal sediment. Int. J. Sys. Bacteriol. 49:441-448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bullock, W. O., J. M. Fernandez, and J. M. Short. 1987. XL1-Blue: a high efficiency plasmid transforming recA Escherichia coli strain with beta-galactosidase selection. Biotechniques 5:376-378. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Degelau, A., T. Scheper, J. E. Bailey, and C. Guske. 1995. Fluorometric measurement of poly-β-hydroxybutyrate in Alcaligenes eutrophus by flow cytometry and spectrofluorometry. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 42:653-657. [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Lorenzo, V., M. Herrero, U. Jakubzik, and K. N. Timmis. 1990. Mini-Tn5 transposon derivatives for insertion mutagenesis, promoter probing, and chromosomal insertion of cloned DNA in gram-negative eubacteria. J. Bacteriol. 172:6568-6572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dinh, T., I. T. Paulsen, and M. H. Saier, Jr. 1994. A family of extracytoplasmic proteins that allow transport of large molecules across the outer membranes of gram-negative bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 176:3825-3831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dong, Q., and M. Mergeay. 1994. Czc/Cnr efflux: a three-component chemiosmotic antiport pathway with a 12-trans-membrane-helix protein. Mol. Microbiol. 14:185-187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dyksterhouse, S. E., J. P. Gray, R. P. Herwig, J. C. Lara, and J. T. Staley. 1995. Cycloclasticus pugetii gen. nov., sp. nov., an aromatic hydrocarbon-degrading bacterium from marine sediments. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 45:116-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fath, M. J., and R. Kolter. 1993. ABC transporters: bacterial exporters. Microbiol. Rev. 57:995-1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fernandez-Martínez, J., M. J. Pujalte, J. García-Martínez, M. Mata, E. Garay, and F. Rodríguez-Varela. 2003. Description of Alcanivorax venustensis sp. nov. and reclassification of Fundibacter jadensis DSM 12178T (Bruns and Berthe-Corti 1999) as Alcanivorax jadensis comb. nov., members of the emended genus Alcanivorax. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 53:331-338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gacesa, P. 1998. Bacterial alginate biosynthesis: recent progress and future prospects. Microbiology 144:1133-1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gauthier, M. J., B. Lafay, R. Christen, L. Fernandez, M. Acquaviva, P. Bonin, and J. C. Bertrand. 1992. Marinobacter hydrocarbonoclasticus gen. nov., sp. nov., a new, extremely halotolerant, hydrocarbon-degrading marine bacterium. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 42:568-576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goutx, M., M. Acquaviva, and J. C. Bertrand. 1990. Cellular and extracellular carbohydrates and lipids from marine bacteria during growth on soluble substrates and hydrocarbons. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 61:291-296. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grabert, E., J. Wingender, and U. K. Winkler. 1990. An outer membrane protein characteristic of mucoid strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 56:83-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Head, I. M., D. M. Jones, and F. M. Röling. 2006. Marine microorganisms make a meal of oil. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 4:173-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hedlund, B. P., A. D. Geiselbrecht, T. J. Bair, and J. T. Staley. 1999. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon degradation by a new marine bacterium, Neptunomonas naphthovorans gen. nov., sp. nov. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:251-259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hmiel, S. P., M. D. Snavely, C. G. Miller, and M. E. Maguire. 1986. Magnesium transport in Salmonella typhimurium: characterization of magnesium influx and cloning of a transport gene. J. Bacteriol. 168:1444-1450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hohn, B., and J. Collins. 1980. A small cosmid for efficient cloning of large DNA fragments. Gene 11:291-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hvorup, R. N., B. Winnen, A. B. Chang, Y. Jiang, X.-F. Zhou, and M. H. Saier, Jr. 2003. The multidrug/oligosaccharidyl-lipid/polysaccharide (MOP) exporter superfamily. Eur. J. Biochem. 270:799-813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Juni, E., and A. Janik. 1969. Transformation of Acinetobacter calco-aceticus (Bacterium anitratum). J. Bacteriol. 98:281-288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kalscheuer, R., T. Stöveken, U. Malkus, R. Reichelt, P. N. Golyshin, J. S. Sabirova, M. Ferrer, K. N. Timmis, and A. Steinbüchel. 2007. Analysis of storage lipid accumulation in Alcanivorax borkumensis: evidence for alternative triacylglycerol biosynthesis routes in bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 189:918-928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kasai, Y., H. Kishira, T. Sasaki, K. Syutsubo, K. Watanabe, and S. Harayama. 2002. Predominant growth of Alcanivorax strains in oil-contaminated and nutrient-supplemented sea water. Environ. Microbiol. 4:141-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kimura, K., M. Yamaoka, and Y. Kamisaka. 2004. Rapid estimation of lipids in oleaginous fungi and yeasts using Nile red fluorescence. J. Microbiol. Methods 56:331-338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Madgwick, J., A. Haug, and B. Larsen. 1978. Ionic requirements of alginate-modifying enzymes in the marine alga Pelvetia canaliculata (L.) Dcne. et Thur. Bot. Mar. 21:1-3. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maneerat, S. 2005. Biosurfactants from marine microorganisms. Songklanakarin J. Sci. Technol. 27:1263-1272. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Margolis, G., and J. P. Pickett. 1956. New applications of the luxol fast blue myelin stain. Lab. Invest. 5:459-474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marmur, J. 1961. A procedure for the isolation of desoxyribonucleic acid from microorganisms. J. Mol. Biol. 1:208-218. [Google Scholar]

- 39.McMillian, M. K., E. R. Grant, Z. Zhong, J. B. Parker, L. Li, R. A. Zivin, M. E. Burczynski, and M. D. Johnson. 2001. Nile red binding to HepG2 cells: an improved assay for in vitro studies of hepatosteatosis. In Vit. Mol. Toxicol. 14:177-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nies, D. H. 2003. Efflux-mediated heavy metal resistance in prokaryotes. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 27:313-339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nies, D. H., and S. Silver. 1995. Ion efflux systems involved in bacterial metal resistances. J. Ind. Microbiol. 14:186-199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nikaido, H. 1994. Prevention of drug access to bacterial targets: permeability barriers and active efflux. Science 264:382-388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Paulsen, I. T., J. H. Park, S. P. Choi, and M. H. Saier, Jr. 1997. A family of Gram-negative bacterial outer membrane factors that function in the export of proteins, carbohydrates, drugs and heavy metals from Gram-negative bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 156:1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pedrós-Alió, C., J. Mas, and R. Guerrero. 1985. The influence of poly-β-hydroxybutyrate accumulation on cell volume and buoyant density in Alcaligenes eutrophus. Arch. Microbiol. 143:178-184. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rehm, B. H. A., and S. Valla. 1997. Bacterial alginates: biosynthesis and applications. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 48:281-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rehm, B. H. A., G. Boheim, J. Tommassen, and U. K. Winkler. 1994. Overexpression of algE in Escherichia coli: subcellular localization, purifcation, and ion channel properties. J. Bacteriol. 176:5639-5647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rehm, B. H. A., G. Grabert, J. Hein, and U. K. Winkler. 1994. Antibody response of rabbits and cystic fibrosis patients to alginate-specific outer membrane protein of a mucoid strain of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microb. Pathog. 16:43-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Remminghorst, U., and B. H. A. Rehm. 2006. Bacterial alginates: from biosynthesis to applications. Biotechnol. Lett. 28:1701-1712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ron, E. Z., and E. Rosenberg. 2002. Biosurfactants and oil bioremediation. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 13:249-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rontani, J. F., P. C. Bonin, and J. K. Volkman. 1999. Production of wax esters during aerobic growth of marine bacteria on isoprenoid compounds. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:221-230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sabirova, J. S., M. Ferrer, H. Lünsdorf, V. Wray, R. Kalscheuer, A. Steinbüchel, K. N. Timmis, and P. N. Golyshin. 2006. Mutation in a “tesB-like” hydroxyacil-coenzyme A-specific thioesterase gene causes hyperproduction of extracellular polyhydoxyalkanoates by Alcanivorax borkumensis SK2. J. Bacteriol. 188:8452-8459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Saier, Jr., H. M., R. Tam, A. Reizer, and J. Reizer. 1994. Two novel families of bacterial membrane proteins concerned with nodulation, cell division and transport. Mol. Microbiol. 11:841-847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 54.Sanger, F., S. Nicklen, and A. R. Coulson. 1977. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 74:5463-5467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Scatamburlo-Moreira, M. A., E. Chartone de Souza, and C. Alencar de Moraes. 2004. Multidrug efflux systems in Gram-negative bacteria. Braz. J. Microbiol. 35:19-28. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schlegel, H. G., H. Kaltwasser, and G. Gottschalk. 1961. Ein submersverfahren zur kultur wasserstoffoxidierender bakterien: wachstums-physiologische untersuchungen. Arch. Mikrobiol. 38:209-222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schneiker, S., V. A. P. Martins dos Santos, D. Bartels, T. Bekel, M. Brecht, J. Buhrmester, T. N. Chernikova, R. Denaro, M. Ferrer, C. Gertler, A. Goesmann, O. V. Golyshina, F. Kaminski, A. N. Khachane, S. Lang, B. Linke, A. C. McHardy, F. Meyer, T. Nechitaylo, A. Pühler, D. Regenhardt, O. Rupp, J. S. Sabirova, W. Selbitschka, M. M. Yakimov, K. N. Timmis, F. J. Vorhölter, S. Weidner, O. Kaiser, and P. N. Golyshin. 2006. Genome sequence of the ubiquitous hydrocarbon-degrading marine bacterium Alcanivorax borkumensis. Nat. Biotechnol. 24:997-1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Silver, S., and L. T. Phung. 1996. Bacterial heavy metal resistance: new surprises. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 50:753-789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Simon, R., U. Priefer, and A. Pühler. 1983. A broad host-range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering transposon mutagenesis in Gram negative bacteria. Biotechnology (NY) 1:784-791. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Singer, M. E., S. M. Tyler, and W. R. Finnerty. 1985. Growth of Acinetobacter sp. strain HO1-N on n-hexadecanol: physiological and ultrastructural characteristics. J. Bacteriol. 162:162-169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Siporin, C., and J. J. Cooney. 1975. Extracellular lipids of Cladosporium (Amorphotheca) resinae grown on glucose or on n-alkanes. Appl. Microbiol. 29:604-609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Spiekermann, P., B. H. A. Rehm, R. Kalscheuer, D. Baumeister, and A. Steinbüchel. 1999. A sensitive, viable-colony staining method using Nile red for direct screening of bacteria that accumulate polyhydroxyalkanoic acids and other lipid storage compounds. Arch. Microbiol. 171:73-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tseng, T.-T., K. S. Gratwick, J. Kollman, D. Park, D. H. Nies, A. Goffeau, and M. H. J. Saier. 1999. The RND superfamily: an ancient, ubiquitous and diverse family that includes human disease and development proteins. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1:107-125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wältermann, M., A. Hinz, H. Robenek, D. Troyer, R. Reichelt, U. Malkus, H. J. Galla, R. Kalscheuer, T. Stöveken, P. von Landenberg, and A. Steinbüchel. 2005. Mechanism of lipid body formation in bacteria: how bacteria fatten up. Mol. Microbiol. 55:750-763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wältermann, M., and A. Steinbüchel. 2005. Neutral lipid bodies in prokaryotes: recent insights into structure, formation, and relationship to eukaryotic lipid depots. J. Bacteriol. 187:3607-3619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wältermann, M., and A. Steinbüchel. 2006. Wax ester and triacylglycerol inclusions, p. 137-166. In J. M. Shively (ed.), Inclusions in prokaryotes, vol. 1. Springer-Verlag, Heidelberg, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wong, T. Y., L. A. Preston, and N. L. Schiller. 2000. Alginate lyase: review of major sources and enzyme characteristics, structure-function analysis, biological roles, and applications. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 54:289- 340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yakimov, M. M., P. N. Golyshin, S. Lang, E. R. B. More, W. R. Abraham, H. Lünsdorf, and K. N. Timmis. 1998. Alcanivorax borkumensis gen. nov., sp. nov., a new, hydrocarbon-degrading and surfactant-producing marine bacterium. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 48:339-348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yakimov, M. M., K. N. Timmis, and P. N. Golyshin. 2007. Obligate oil-degrading marine bacteria. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 18:257-266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]