Abstract

Bacterial sensing of environmental signals plays a key role in regulating virulence and mediating bacterium-host interactions. The sensing of the neuroendocrine stress hormones epinephrine (adrenaline) and norepinephrine (noradrenaline) plays an important role in modulating bacterial virulence. We used MudJ transposon mutagenesis to globally screen for genes regulated by neuroendocrine stress hormones in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. We identified eight hormone-regulated genes, including yhaK, iroC, nrdF, accC, yedP, STM3081, and the virulence-related genes virK and mig14. The mammalian α-adrenergic receptor antagonist phentolamine reversed the hormone-mediated effects on yhaK, virK, and mig14 but did not affect the other genes. The β-adrenergic receptor antagonist propranolol had no activity in these assays. The virK and mig14 genes are involved in antimicrobial peptide resistance, and phenotypic screens revealed that exposure to neuroendocrine hormones increased the sensitivity of S. Typhimurium to the antimicrobial peptide LL-37. A virK mutant and a virK mig14 double mutant also displayed increased sensitivity to LL-37. In contrast to enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli (EHEC), we have found no role for the two-component systems QseBC and QseEF in the adrenergic regulation of any of the identified genes. Furthermore, hormone-regulated gene expression could not be blocked by the QseC inhibitor LED209, suggesting that sensing of hormones is mediated through alternative signaling pathways in S. Typhimurium. This study has identified a role for host-derived neuroendocrine stress hormones in downregulating S. Typhimurium virulence gene expression to the benefit of the host, thus providing further insights into the field of host-pathogen communication.

Bacterial sensing of environmental signals plays a key role in regulating virulence gene expression and bacterium-host interactions. It is increasingly recognized that detection of host-derived molecules, such as the neuroendocrine stress hormones (catecholamines) epinephrine (adrenaline) and norepinephrine (noradrenaline), plays an important role in modulating bacterial virulence (29, 42).

Physical and psychological stress has been linked to increased severity and susceptibility to infection in humans and other animals (23, 42), and epinephrine/norepinephrine levels are an important factor in this. Stress triggers an increase in plasma epinephrine levels (31), and plasma levels of epinephrine and norepinephrine have been reported to increase with patients suffering from postoperative sepsis compared to patients with no complications (32). Administration of norepinephrine and epinephrine to otherwise healthy subjects increases the severity of bacterial infections, including Clostridium perfringens in humans and enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli (EHEC) in calves (42, 63, 65). Treatment with norepinephrine also increases the virulence of Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis in chicks and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium in mice, with a substantial increase in bacterial numbers recovered from the cecum and liver in both cases (47, 65).

Norepinephrine is found in large concentrations in the gut due to release by gastrointestinal neurones; indeed up to half the norepinephrine in the body may be produced in the enteric nervous system (ENS) (3). Epinephrine, while not normally found in the gut, is present in the bloodstream and is also produced by macrophages in response to bacteria-derived lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (12, 26). S. Typhimurium is an enteropathogen, can also cross the epithelial barrier to cause systemic infection, and will therefore encounter both these molecules in the normal infection cycle.

Phenotypes induced by stress hormones in bacteria include increased adherence of EHEC to bovine intestinal mucosa (63), upregulation of type III secretion and Shiga toxin production in EHEC (22, 60), upregulation of type III secretion in Vibrio parahaemolyticus (51), increase in invasion of epithelial cells and breakdown of epithelial tight junctions by Campylobacter jejuni (15), affected motility and expression of iron uptake genes in S. Typhimurium (8, 9, 36), and modulated virulence in Borrelia burgdorferi (59). Epinephrine and norepinephrine can overcome the growth inhibition of many bacteria, including Salmonella, in serum-containing media (13, 43), due to the ability to act as a siderophore to facilitate iron uptake (13, 28, 47).

Norepinephrine and epinephrine also interact with bacterial quorum-sensing (QS) systems. QS is a process of bacterial cell-cell communication in which each cell produces small signal molecules termed “autoinducers” (AIs), which regulate gene expression when a critical threshold concentration and therefore population density have been reached. QS affects diverse processes, including motility, virulence, biofilm formation, type III secretion, and luminescence (6, 64).

The EHEC AI-3 QS system is important for motility and expression of the type III secretion system encoded by the locus of enterocyte effacement (LEE) (60). AI-3 sensing and signal transduction are mediated via the QseBC and QseEF two-component systems, respectively. Epinephrine and norepinephrine can substitute for AI-3, causing cross talk between the two signaling systems and induction of type III secretion and motility (57, 60). The sensor kinase QseC is autophosphorylated upon binding either epinephrine or norepinephrine (14), demonstrating the presence of adrenergic receptors in bacteria. These adrenergic phenotypes can also be blocked by the mammalian α- and β-adrenergic antagonists phentolamine and propranolol, although it should be noted that QseC is blocked only by the former (14, 60). This suggests the occurrence of cross talk between bacterial and mammalian cell signaling systems and the existence of multiple bacterial adrenergic sensors.

To elucidate the role of host-derived stress hormones in the physiology and pathogenicity of S. Typhimurium, we used MudJ transposon mutagenesis to screen globally for epinephrine- and norepinephrine-regulated genes in S. Typhimurium.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium strains, plasmids, and primers are shown in Table 1. Bacteria were grown overnight in 5 ml LB broth at 37°C and 200 rpm. A total of 25 μl of overnight broth was used to inoculate 25 ml fresh LB, or 250 μl to inoculate 25 ml M9 minimal media (48) supplemented with 0.3% Casamino Acids and 40 μg/ml histidine, and the bacteria were grown in 250-ml conical flasks at 37°C and 200 rpm. LB medium is commonly used to mimic intestinal conditions (54, 62). We also used minimal media, as much previous work investigating catecholamines has been done in SAPI-serum minimal media (13, 28, 43). As supplementation with catecholamines drastically affects growth rate in this media, we used M9 to negate the possibility of growth rate indirectly affecting the phenotypes seen.

TABLE 1.

Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium strains, plasmids, and primers used in this studya

| Strain, plasmid, or primer | Description, genotype, or sequence | Reference, source, and/or comment |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| SL1344 | Wild-type parent strain | 34 |

| LT2 TPA356 | MudJ donor strain, hisD9953::MudJ, hisA9944::MudI | 35 |

| SL1344-YK | yhaK::MudJ | This study |

| SL1344-VK | virK::MudJ | This study |

| SL1344-MIG | mig14::MudJ | This study |

| SL1344-IC | iroC::MudJ | This study |

| SL1344-YP | yedP::MudJ | This study |

| SL1344-3 | STM3081::MudJ | This study |

| SL1344-AC | accC::MudJ | This study |

| SL1344-NF | nrdF::MudJ | This study |

| SL1344-pYK | SL1344 pMK1lux-PyhaK | This study |

| SL1344-pVK | SL1344 pMK1lux-PvirK | This study |

| SL1344-pMIG | SL1344 pMK1lux-Pmig14 | This study |

| SL1344-pACC | SL1344 pMK1lux-PaccB | This study |

| SL1344-pYP | SL1344 pMK1lux-PyedP | This study |

| SL1344-p3 | SL1344 pMK1lux-PSTM3083 | This study |

| SL1344-pIRO | SL1344 pMK1lux-PiroB | This study |

| SL1344-pNRD | SL1344 pMK1lux-PnrdH | This study |

| SL1344 basS | SL1344 ΔbasS | 36 |

| SL1344 qseBC | SL1344 ΔqseBC | This study |

| SL1344 qseF | SL1344 ΔqseF | This study |

| SL1344 qseBCqseF | SL1344 ΔqseBC ΔqseF | This study |

| SL1344 virK | SL1344 ΔvirK | This study |

| SL1344 mig14 | SL1344 Δmig14 | This study |

| SL1344 virKmig14 | SL1344 ΔvirK Δmig14 | This study |

| SL1344 tonB | SL1344 ΔtonB | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pPCR-Script | Sequencing vector | Stratagene |

| pMK1lux | pBR322 with luxCDABE operon and MCS | 36 |

| pMK1lux-PyhaK | pMK1lux with PyhaK cloned as 5′EcoRI-3′BamHI fragment | This study |

| pMK1lux-PvirK | pMK1lux with PvirK cloned as 5′EcoRI-3′BamHI fragment | This study |

| pMK1lux-Pmig14 | pMK1lux with Pmig14 cloned as 5′EcoRI-3′BamHI fragment | This study |

| pMK1lux-PaccB | pMK1lux with PaccB cloned as 5′EcoRI-3′BamHI fragment | This study |

| pMK1lux-PyedP | pMK1lux with PyedP cloned as 5′EcoRI-3′BamHI fragment | This study |

| pMK1lux-PSTM3083 | pMK1lux with PSTM3083 cloned as 5′EcoRI-3′BamHI fragment | This study |

| pMK1lux-PiroB | pMK1lux with PiroB cloned as 5′EcoRI-3′BamHI fragment | This study |

| pMK1lux-PnrdH | pMK1lux with PnrdH cloned as 5′EcoRI-3′BamHI fragment | This study |

| Primers | ||

| MudOut | CCGAATAATCCAATGTCCTCCCGGT | Inverse PCR (2) |

| MudTaq | AGTGCGCAATAACTTGCTCTCGTTC | Inverse PCR (2) |

| Universal-PCR | GTAAAACGACGGCCAGTGAGCGCGC | Inverse PCR (2) |

| yhaK 5 | GCG GAATTC TCCAGCAATACCCGCCCGCG | Cloning |

| yhaK 3 | GCG GGATCC CGTTATTAACCTCTCTTTAC | Cloning |

| virK 5 | GCG GAATTC CCTCACCCCAGTCA | Cloning |

| virK 3 | GCG GGATCC CTACTACTCGATCG | Cloning |

| mig14 5 | GCG GAATTC ATACGCGGATGTGC | Cloning |

| mig14 3 | GCG GGATCC TGACTTAGCTTACT | Cloning |

| accB 5 | GCG GAATTC GTGAACTGTGCGGTCGATTG | Cloning |

| accB 3 | GCG GGATCC GAGTGGGTTCCGTACTCTTTG | Cloning |

| yedP 5 | GCG GAATTC GCGGGTGAGCGTAGACGGACG | Cloning |

| yedP 3 | GCG GGATTC GGGTCATGGATTGAGAGC | Cloning |

| STM3083 5 | GTG GAATTC CCGTAACTGATGTTCTTAGG | Cloning |

| STM3083 3 | GTG GGATCC ACTGGCGAGCTATGGTGTC | Cloning |

| iroB 5 | GCG GAATTC TCGAACGGTGACGTTAAAGC | Cloning |

| iroB 3 | GCG GGATCC AATACGCATGAGAAATCCTC | Cloning |

| nrdH 5 | GCG GAATTC AATCAGCGATCTGACCTTCG | Cloning |

| nrdH 3 | GCG GGATCC TGCTCATGATTCGTATTTCC | Cloning |

| qseBC P1 | GTTAACTGACGGCAACGCGAGTTACCGCAAGGAAGAACAGGTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTC | λ Red |

| qseBC P4 | AAATGTGCAAAGTCTTTTGCGTTTTTGGCAAAAGTCTCTGATTCCGGGGATCCGTCGACC | λ Red |

| qseBC-5 | ACATCGCCTGCGGCGACAAG | λ Red |

| qseBC-3 | GCGGTGCGGTGAAATTAGCA | λ Red |

| qseF P1 | GGCGCCGTCGCCGTCACAAGATGAGGTAACGCCATGATAAGTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTC | λ Red |

| qseF P4 | TTAAACGTAACATATTTCGCGCTACTTTACGGCATGAAAAATTCCGGGGATCCGTCGACC | λ Red |

| qseF-5 | CAAACCCGCGACGTCTGAAG | λ Red |

| qseF-3 | GTCGCCTGTGTTTTGATCGG | λ Red |

| virK P1 | CCGTCTCGGTTATAAGTCTATCGAGTAGTAGAGCCGTAGTGTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTC | λ Red |

| virK P4 | GAACGGTAGCAGGATCTGCACATCCGCGTATGAAATAGTTATTCCGGGGATCCGTCGACC | λ Red |

| virK-5 | CGTTTAACTCAATCAGGCTA | λ Red |

| virK-3 | CAGATTTCAAAAGATCCGCT | λ Red |

| mig14 P1 | TCTTATTCCCTTCACCATAACGTCATCGATTAGCATGTTAGTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTC | λ Red |

| mig14 P4 | TTCGAGTAATTGTCATTATGATTATATGGTGGTTAACTTAATTCCGGGGATCCGTCGACC | λ Red |

| mig14-5 | CATGTTATGATCAACATCTT | λ Red |

| mig14-3 | CCGAGTATAGTGTAAGTGAA | λ Red |

| tonB P1 | ATTCAGCTCTGGTTTTTCAACTGAAACGATTATGACTTCAGTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTC | λ Red |

| tonB P4 | CAGCAGGTGATGGTATATTCCTGGCTGGCGGCGCCAGAGAATTCCGGGGATCCGTCGACC | λ Red |

| tonB-5 | GATTGCTATTTGCATTTAAA | λ Red |

| tonB-3 | AGTATACCCGCTTACGCCGC | λ Red |

Restriction sites are underlined.

General physiological and molecular biological manipulations were performed according to standard laboratory protocols (58). Antibiotics were added at the following concentrations: kanamycin, 50 μg/ml, and ampicillin, 100 μg/ml.

Epinephrine/norepinephrine hydrochloride (Sigma) was added to a final concentration of 50 μM or 500 μM in distilled water (dH2O). Propranolol and phentolamine (Sigma) were added to a final concentration of 500 μM in dH2O.

Chemical synthesis of LED209.

N-phenyl-4-{[(phenylamino)thioxomethyl]amino}-benzenesulfonamide (LED209) was synthesized in three steps essentially by the procedure described by Rasko et al. (55). Reaction of aniline with 4-acetamidobenzenesulfonyl chloride in ethanol in the presence of sodium acetate at room temperature afforded 4-acetamido-N-phenyl-benzenesulfonamide in 80% yield as a white solid (melting point, 207 to 209°C). The acid hydrolysis of this product with 6 M HCl in ethanol at reflux gave 4-amino-N-phenyl-benzenesulfonamide as a white solid in 98% yield. In the final step, the 4-amino-N-phenyl-benzenesufonamide product was condensed with phenylisothiocyanate in dry tetrahydrofuran in the presence of triethylamine at reflux for 48 h. After concentration, the crude oily product was purified by flash chromatography on silica gel in acetone-hexane (1:3) to deliver LED209 as a white crystalline solid (melting point of 161 to 163°C) in 25% yield. The structure and purity of the product was unequivocally confirmed by 1H NMR, which showed the expected resonances at δ 7.00 to 7.47 (9H, 5 × m, ArH), 7.70 (5H, s, Ph), 10.07 (2H, br s, NHCSNH), and 10.23 (1H, br s, SO2NH). The structure was further confirmed by electrospray mass spectrometry (ES-MS) (negative-ion mode), which displayed the correct molecular ion at an m/z of 382 (M-H, C19H17N3O2S2 requires an m/z of 383) and expected fragmentation ions at m/z values of 348 (M-H-H2S), 289 (M-H-PhNH2), and 247 (M-H-Ph-N=C=S). LED209 was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) at 50 mM and then diluted in dH2O as stated.

MudJ mutagenesis.

MudJ mutagenesis was done as described previously (35). Briefly, a phage lysate of strain TPA356 was prepared according to standard laboratory protocol (58) and transduced into SL1344. Transductants were plated onto no-carbon E salts (NCE) plates (19) with 100 μl 50 mM epinephrine overlaid on the agar and incubated at 37°C for 48 h. Resulting colonies were patched to MacConkey agar plates (Sigma), with or without an overlay of 100 μl 50 mM epinephrine, to give a final concentration of approximately 250 μM.

Genomic sequencing.

MudJ gene insertions were identified using inverse PCR as previously described (2). Briefly, genomic DNA was isolated using a DNeasy blood and tissue kit (Qiagen), digested with TaqαI and self ligated with T4 DNA ligase. One μl was used as a template for PCR using Phusion polymerase (New England Biolabs) and primers MudOut and MudTaq (Table 1). PCR products were purified using PCR cleanup columns (Invitrogen) and ligated into the SmaI site of pPCR-Script (Stratagene). Plasmid DNA was purified using an Invitrogen miniprep kit and sequenced with primer Universal-PCR. Sequencing was performed at Pinnacle, Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, United Kingdom. Sequence homologies were identified using BLAST (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi).

β-Galactosidase assays.

Strains were grown in 25-ml volumes in M9 minimal medium for 2.5 h or LB for 3.5 h (for yhaK::MudJ), 50 μM epinephrine/norepinephrine was added, and samples were removed after 30 min. β-Galactosidase assays were performed using the chloroform-sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) permeabilization method as previously described (48). Experiments were carried out at least three times.

Construction of luciferase reporters and luciferase assays.

Promoter regions were identified using the Berkeley Drosophila Genome Project (http://www.fruitfly.org/seq_tools/promoter.html) and cloned into the EcoRI and BamHI restriction sites of plasmid pMK1lux (36), using primers listed in Table 1.

Promoter-luciferase expression assays were carried out in 200 μl LB or M9 in 96-well plates at 37°C, with hormones, adrenergic antagonists, and LED209 added immediately after inoculation. Optical density (OD) and luminescence were measured in a Tecan Infinite200 spectrophotometer every 15 min for 16 h, and the maximum luminescence/OD at 600 nm (OD600) of this was recorded.

Construction of gene knockouts.

Genes were deleted using lambda Red mutagenesis (18). Briefly, primers P1 and P4 (Table 1) were used to amplify the kanamycin cassette from plasmid pKD13, which was transformed into the parent strain containing plasmid pKD46. The kanamycin cassette was removed using the FLP recombinase expressed from the temperature-sensitive plasmid pCP20, and mutations were confirmed by PCR.

Antimicrobial peptide resistance assays.

Strains were grown in M9 for 2.5 h, epinephrine or norepinephrine was added, and incubation was continued for 30 min. Assays were done as previously described (36). Briefly, cultures were diluted to ∼106 CFU/ml, and 50 μl was inoculated into a 96-well plate and incubated with 100 μl LL-37 (5 μg/ml) (Phoenix Pharmaceuticals) for 1 h at 37°C and 200 rpm. Survival rates were determined by serial dilutions and viable counts on LB plates. Percent survival was calculated from the numbers of surviving bacteria divided by the numbers for the initial inoculum.

RESULTS

A genetic screen to identify genes regulated by epinephrine in S. Typhimurium.

The detection of host molecules, such as epinephrine and norepinephrine, has an increasingly recognized role in bacterial virulence and host infection (14, 51, 59, 65). We used a global screen to identify epinephrine-regulated pathways in S. Typhimurium, by using MudJ transposon mutagenesis to produce random chromosomal lacZ gene insertions which were screened for differential regulation with epinephrine. A transposon library of 10,000 S. Typhimurium mutants was patched onto MacConkey agar plates with or without epinephrine, and mutants that showed a color change indicative of differential regulation of the inserted lacZ gene by epinephrine were isolated.

Eight mutants were isolated; seven mutants carried genes that were downregulated by epinephrine, and one carried a gene that was upregulated by epinephrine.

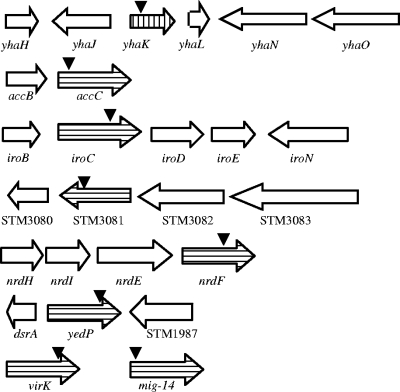

Inverse PCR was used to amplify and clone the DNA flanking each MudJ insertion, which was then sequenced. The identities of the genes are listed in Table 2, and the chromosomal organization of the genes is shown in Fig. 1. A single gene was upregulated by epinephrine and was identified as yhaK, whose product is a putative cytoplasmic protein of unknown function. Downregulated genes included virK and mig14, which are important for virulence and survival in a mouse model, survival in macrophages, and resistance to the antimicrobial peptides polymyxin B and CRAMP (cathelicidin-related antimicrobial peptide) (10, 11, 20).

TABLE 2.

The identities of MudJ gene insertions affected by epinephrine in S. Typhimurium

| Locus tag | Gene identity | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Epinephrine-upregulated gene | ||

| STM3236 | yhaK | Putative cytoplasmic protein |

| Epinephrine-downregulated genes | ||

| STM2781 | virK | Virulence protein |

| STM2782 | mig14 | Virulence protein |

| STM2774 | iroC | ABC transporter |

| STM3380 | accC | Acetyl-CoA carboxylase subunit |

| STM2808 | nrdF | Ribonucleotide diphosphate reductase subunit |

| STM1986 | yedP | Putative mannosyl-3-phosphoglycerate phosphatase |

| STM3081 | Putative l-lactate/malate dehydrogenase |

FIG. 1.

Chromosomal organization of epinephrine-regulated genes. MudJ insertions are indicated by arrows. Upregulated genes and downregulated genes are shown with vertical stripes and horizontal stripes, respectively.

A fatty acid biosynthesis gene, accC, which encodes the biotin carboxylase subunit of acetyl-coenzyme A (CoA) carboxylase and catalyzes the first committed step of fatty acid biosynthesis, was among the downregulated genes (16).

A siderophore transport gene, iroC, part of the gene locus involved in the synthesis, transport, and utilization of the siderophore salmochelin, a glucosylated form of enterobactin (17, 33), was also downregulated.

A ribonucleotide diphosphate reductase (RRase) subunit, nrdF, which catalyzes conversion of ribonucleotides to deoxyribonucleotides for DNA synthesis, was also downregulated (45, 50, 52). The gene STM3081, which encodes a putative l-lactate/malate dehydrogenase, and yedP, which encodes a putative mannosyl-3-phosphoglycerate phosphatase, both of uncharacterized function, were also downregulated by epinephrine.

Epinephrine and norepinephrine regulate gene expression in similar manners.

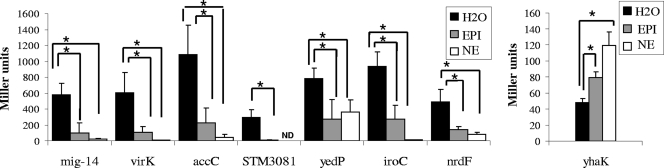

β-Galactosidase assays of isolated mutants grown to mid-exponential phase showed the same regulatory phenotype upon addition of 50 μM epinephrine as seen in the initial screen using MacConkey agar plates. The addition of norepinephrine also resulted in the same phenotype, suggesting that both hormones may act in similar manners to affect S. Typhimurium gene expression (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Expression of isolated MudJ insertions. Cells were grown to mid-exponential phase, 50 μM epinephrine (EPI) or 50 μM norepinephrine (NE) was added, and β-galactosidase activity (in Miller units) was determined after 30 min. Asterisks indicate significant difference using Student's t test (P < 0.01). Error bars are shown. Experiments were performed at least three times. ND, result not determined.

To further confirm the epinephrine- and norepinephrine-regulated phenotypes, promoter-luciferase reporter constructs for each gene or gene operon shown in Fig. 1 were made and introduced into the wild-type background. The activity of each promoter was measured by luminescence produced by the luciferase. The promoters of STM3083, virK, mig14, nrdH, accB, iroB, and yedP were all downregulated by epinephrine and norepinephrine, and expression of yhaK was upregulated by epinephrine and norepinephrine (Fig. 3). These results are in agreement with the β-galactosidase assays, confirming the initial observations. Each hormone was added to 500 μM for luciferase assays to induce the same phenotype seen in the β-galactosidase assays. This may be explained by differences in growth conditions between the two assays; β-galactosidase assays were done in 25-ml volumes in shaking flasks with good aeration, whereas luciferase assays were conducted in 200-μl volumes in 96-well plates with occasional agitation.

FIG. 3.

Maximum expression of promoter-luciferase fusions in the presence of 500 μM EPI, NE, or phentolamine (PE). Luminescence is expressed as relative light units (RLU) per OD of culture standardized to water control. Asterisks indicate significant difference using Student's t test (P < 0.01). Error bars are shown. Experiments were performed at least three times for each fusion.

Epinephrine/norepinephrine-mediated gene expression is blocked by the α-adrenergic antagonist phentolamine.

Some neuroendocrine stress hormone-mediated phenotypes, such as upregulation of type III secretion and motility in EHEC, are blocked by mammalian adrenergic antagonists, such as phentolamine (PE) (α-blocker) and propranolol (PO) (β-blocker) (14, 60). The neuroendocrine stress hormone-associated growth promotion of S. Typhimurium in SAPI-serum minimal media is also blocked by PE but not PO (27), and it was reported that the motility of S. Typhimurium is reduced by PE (8).

We investigated whether PE or PO could block the epinephrine- and norepinephrine-regulated phenotypes seen with S. Typhimurium by measuring the luminescence of promoter-luciferase constructs for each identified gene. The β-blocker PO did not reverse the epinephrine- and norepinephrine-regulated phenotype for any gene (data not shown). On the other hand, addition of the α-blocker PE could reverse the epinephrine- and norepinephrine-mediated regulation of yhaK, virK, and mig14, while having no significant effect on the other epinephrine/norepinephrine-regulated genes (see Fig. 3).

Epinephrine and norepinephrine decrease antimicrobial peptide resistance.

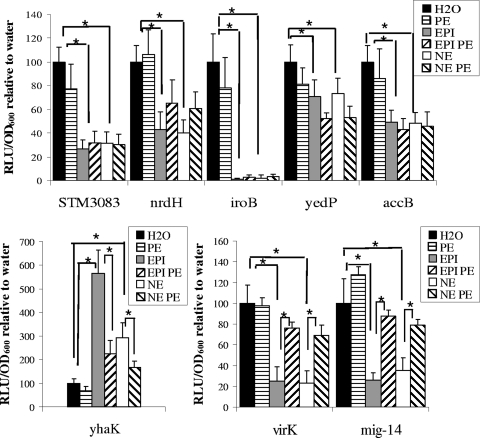

virK and mig14 are involved in resistance to the murine antimicrobial peptide CRAMP, both showing decreased survival rates in relation to the wild type (11). As expression of both genes is decreased by epinephrine and norepinephrine, we investigated whether these hormones affect resistance to cathelicidin LL-37, a human antimicrobial peptide with 67% identity to CRAMP and produced by macrophages and intestinal epithelial cells (4, 53).

Exposure to 500 μM epinephrine or norepinephrine resulted in a significant decrease in resistance to LL-37 to approximately 20% of the water control (Fig. 4A). We constructed precise deletion mutants of virK and mig14, along with a virK mig14 double mutant. The ΔvirK mutant was significantly more sensitive to LL-37 than the wild type, and the Δmig14 mutant showed a slight, nonsignificant decrease in resistance. The ΔvirK Δmig14 double mutant was also more sensitive to LL-37, suggesting that the epinephrine/norepinephrine-induced LL-37 sensitivity is mediated through these genes (Fig. 4B).

FIG. 4.

Sensitivity to the antimicrobial peptide cathelicidin LL-37 (5 μg/ml). Results are expressed as percent survival normalized to wild-type (WT)-H2O. (A) Survival of SL1344 when grown in M9 supplemented with H2O or 500 μM EPI or NE. (B) Survival of SL1344, SL1344 virK mutant, SL1344 mig14 mutant, or SL1344 virK mig14 mutant when grown in M9 without supplementation. Asterisks indicate significant difference to wild-type-H2O using Student's t test (P < 0.01). Error bars are shown. Experiments were performed at least three times.

Recently, we have shown that epinephrine increases sensitivity to polymyxin B in a manner dependent on the two-component system BasSR (36). We saw no change in expression of virK or mig14 in the ΔbasS mutant compared to the wild type, either with or without epinephrine/norepinephrine (data not shown), suggesting that virK and mig14 are regulated by epinephrine/norepinephrine through a mechanism independent of BasSR.

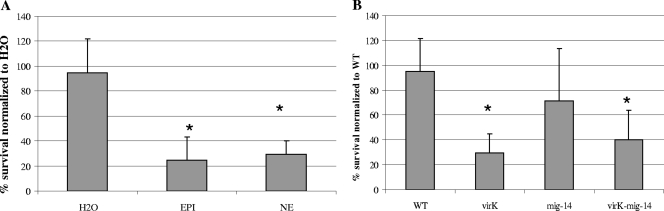

The two-component systems QseBC and QseEF do not mediate adrenergic signaling responses.

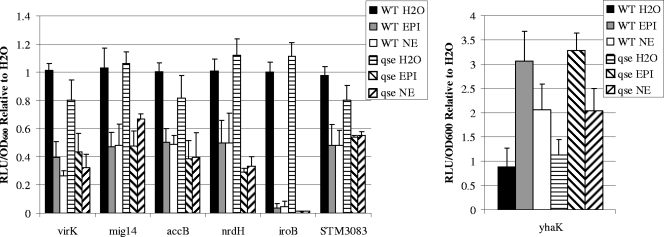

The QseBC two-component system has been identified as an adrenergic receptor in EHEC, regulating the epinephrine-, norepinephrine-, and autoinducer-3-mediated induction of type III secretion and motility (14, 60). The two-component system QseEF is also reported to be involved in adrenergic regulation of type III secretion in EHEC (56, 57). To determine whether QseBC or QseEF are involved in the adrenergic regulation of the identified genes, we constructed a precise qseBC mutant and a mutant of the response regulator qseF, which negates the signaling effect of QseEF in EHEC (56). We introduced the promoter-luciferase reporter constructs for each identified gene into the ΔqseBC and ΔqseF mutants and found no difference in the expression levels of any genes in the ΔqseBC or ΔqseF mutant compared to the wild type upon addition of water, epinephrine, or norepinephrine (data not shown). As many phenotypes attributed to QseBC have been analyzed in a qseC single mutant (8, 14, 55, 60), we constructed and analyzed a qseC single mutant, which also displayed no change in phenotype compared to the wild type (data not shown). Furthermore, we constructed a ΔqseBC ΔqseF triple mutant and introduced each promoter-luciferase construct to investigate the possibility of functional redundancy between the two signaling systems. We found no change in expression in the ΔqseBC ΔqseF mutant compared to the wild type (Fig. 5). This suggests that these genes are regulated through a mechanism independent of known bacterial adrenergic signaling pathways in S. Typhimurium.

FIG. 5.

Maximum expression of promoter-luciferase fusions of stated genes in the WT or ΔqseBC ΔqseF mutant (qse). EPI or NE were added at 500 μM. Luminescence is expressed as RLU per OD of culture standardized to water control. Error bars are shown. Experiments were performed at least three times for each fusion.

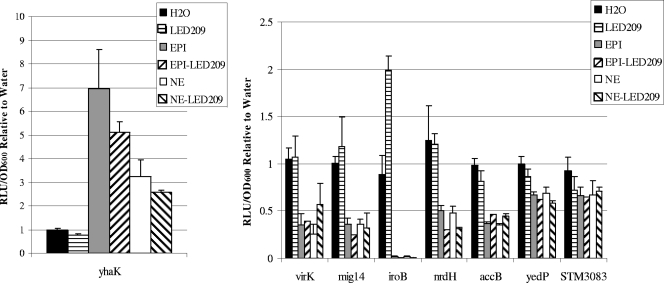

N-phenyl-4-{[(phenylamino)thioxomethyl]amino}-benzenesulfonamide (LED209) was recently identified as inhibiting adrenergic signaling in EHEC by preventing the binding of norepinephrine to QseC and thus blocking QseC-mediated cell signaling at a concentration of 5 pM (55). Addition of LED209 at 5 pM, 5 nM, or 5 μM did not affect expression of any of the identified genes when supplemented with water, epinephrine, or norepinephrine (Fig. 6). This further supports the argument that QseC is not involved in adrenergic gene regulation, at least of these genes, in S. Typhimurium.

FIG. 6.

Maximum expression of promoter-luciferase fusions of stated genes. LED209 was added at 5 μM, and EPI and NE were added at 500 μM. Luminescence is expressed as RLU per OD of culture standardized to water control. Error bars are shown. Experiments were performed at least three times for each fusion.

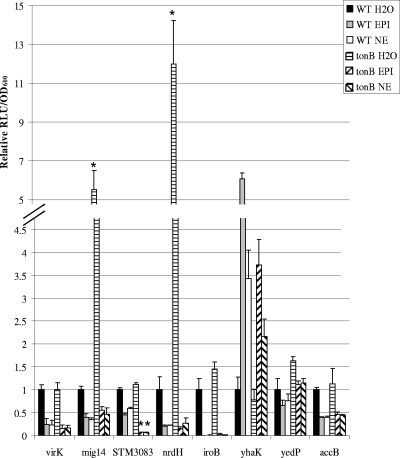

Role of TonB-dependent siderophore uptake in mediating adrenergic sensing.

Some adrenergic phenotypes in bacteria are associated with altered iron uptake via the siderophore enterobactin (13, 28, 47). To determine whether the same mechanism is responsible for the adrenergic regulation of the identified genes, we constructed a tonB mutant defective in siderophore uptake and introduced the promoter-luciferase reporter constructs for each gene. We found that each fusion showed differential regulation upon addition of each hormone, suggesting that the adrenergic regulation is mediated through a mechanism independent of TonB (Fig. 7). We found that expression of mig14 and nrdH were significantly upregulated in the ΔtonB mutant compared to the wild type, suggesting that these genes may be affected by the altered iron status of the cell in the ΔtonB mutant. Upon addition of either hormone, we saw that expression was reduced to approximately the same level in both the wild type and the ΔtonB mutant. These results suggest that in contrast to other adrenergic phenotypes, such as growth promotion in SAPI-serum (13, 28, 47), the adrenergic regulation of these genes is mediated through a mechanism independent of TonB-dependent siderophore transport and iron uptake.

FIG. 7.

Maximum expression of promoter-luciferase fusions of stated genes in the WT or ΔtonB mutant. EPI or NE were added at 500 μM. Luminescence is expressed as RLU per OD of culture standardized to water control. Error bars are shown. Asterisks indicate significant difference between ΔtonB mutant and the respective wild-type values (P < 0.001). Experiments were performed at least three times for each fusion.

DISCUSSION

This work has identified several genes in S. Typhimurium which are regulated by epinephrine and norepinephrine. We have shown adrenergic downregulation of virK and mig14, which are important virulence genes affecting survival and long-term persistence in the host. A mutation in either gene reduces the virulence of S. Typhimurium in a mouse infection model and reduces survival in macrophages. S. Typhimurium mig14 mutants colonize mouse liver/spleen as wild type but fail to replicate after 5 days postinfection, suggesting a role in persistence and the late stages of infection (11, 20). The production of epinephrine recently observed with macrophages (12, 26) may therefore act as a host defense system to reduce the pathogenic potential of Salmonella by downregulating expression of these virulence genes. The downregulation of mig14 may reduce levels of persistent infection and promote clearance of bacteria.

Both virK and mig14 are reported to affect antimicrobial peptide resistance, mutants showing decreased resistance to polymyxin B, and the mouse-derived peptide CRAMP (10, 11). Brodsky et al. (11) showed increased levels of fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled CRAMP associated with virK and mig14 mutant cells compared to the wild type, suggesting that these genes may act to prevent association of antimicrobial peptides with the bacterial cell, although the mechanism is currently unknown.

We have shown a stress hormone-mediated decrease in resistance to the peptide cathelicidin LL-37, a human antimicrobial peptide displaying 67% identity to CRAMP, which is produced by diverse tissues, including the gastrointestinal tract, bone marrow, and macrophages, and has antimicrobial activity against many Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. LL-37 plays an important role in innate immunity, serving to protect epithelia from bacterial pathogens (4, 53). Levels of host stress hormones increase in response to infection (23, 32), and an epinephrine/norepinephrine-mediated increase in sensitivity to LL-37 may act as a host defense system to combat infection, suggesting that bacterial sensing of stress hormones may be a double-edged sword; although bacteria can sense and exploit these molecules, the host can use the same signals to manipulate the bacteria. The effects of epinephrine and norepinephrine are likely to be complex, involving multiple effects on both bacteria and host to influence the outcome of infection. It is possible that the adrenergic downregulation of these genes may confer an advantage to the bacteria under certain in vivo conditions but an unavoidable disadvantage in others; for example, it was recently shown that the downregulation of the lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-modifying enzymes PmrF and PagL causes an increase in sensitivity to polymyxin B but also concomitantly reduces activation of the TLR-4 Toll-like receptors, reducing the host inflammatory response to infection (37, 38, 49).

Pretreatment of mice with norepinephrine enhances recovery of S. Typhimurium from the liver and cecum of infected BALB/c mice by up to 2 logs (47, 65). These mice are genetically highly susceptible to Salmonella infection and usually die a few days postinfection. Mig14 is involved in the later stages of infection; when infecting the less susceptible mouse strain 129Xi/SvJ, mutants initially show no virulence defect but are cleared from the host more effectively after 28 days of infection (11). Speculatively, epinephrine and norepinephrine may initially act to increase bacterial virulence during acute infection, as observed with mice, chicks, and cattle, (44, 47, 65), but the hormone-mediated downregulation of genes such as mig14 may then help clear infection and reduce long-term persistence of bacteria in the host.

Epinephrine has been shown to decrease resistance to polymyxin B through downregulation of the pmr operon, in a manner dependent on the two-component system BasSR (36). We have shown that expression of virK and mig14 is independent of BasSR, suggesting that stress hormones affect LL-37 and polymyxin B resistance by two independent mechanisms. Supporting this theory, the epinephrine-mediated downregulation of the pmr operon and polymyxin sensitivity are blocked by the β-adrenergic antagonist propranolol (36), whereas mig14 and virK expression is blocked by the α-adrenergic antagonist phentolamine.

The two-component system QseBC has been identified as an adrenergic receptor in EHEC, regulating virulence-related processes in a manner blockable by the adrenergic antagonist phentolamine (14, 60). We found that deletion of qseBC had no impact on the regulation of any hormone-regulated gene in this study. Despite this, we have observed that the adrenergic regulation of virK, mig14, and yhaK is blockable by phentolamine. This suggests that a different receptor may be responsible for mediating the adrenergic phenotypes seen with S. Typhimurium. In support of this hypothesis, it has recently been published that QseBC does not affect any of the identified epinephrine/norepinephrine-regulated phenotypes in S. Typhimurium as determined by microarray analysis (46). Furthermore, we found no effect of LED209 on gene expression, although this compound inhibits QseC-mediated adrenergic signaling in EHEC (55), further supporting the theory that adrenergic cell signaling is mediated through different pathways in S. Typhimurium and EHEC. Furthermore, as the remaining identified genes were unaffected by phentolamine or propranolol, this suggests that at least two signaling pathways are present, one blockable by phentolamine and one not.

Epinephrine and norepinephrine have been shown to act as siderophores to increase bacterial iron uptake (13, 28, 36, 47). This increase in intracellular iron may cause the downregulation of genes involved in siderophore synthesis and transport, normally expressed under iron-limiting conditions. We have observed this with the epinephrine/norepinephrine-mediated downregulation of the iro genes, which synthesize and transport the siderophore salmochelin (17, 33). The downregulation of the nrd genes may also be due to changes in iron status, as their expression has been reported to increase during iron-limited conditions (45).

Enterobactin is a major siderophore in Salmonella. A glucosylated form of enterobactin, salmochelin displays lower iron binding affinity but is advantageous under certain conditions (33). Enterobactin is bound by host proteins, such as serum albumin and neutrophil lipocalin NGAL, which is produced by neutrophils and epithelial cells (30, 40), which reduces efficiency of enterobactin-mediated iron acquisition. The glucosylation present on salmochelin inhibits the binding of lipocalin (25), making it more effective for iron acquisition in some environments, such as inside macrophages, but it has been reported that the Salmonella-containing vacuole (SCV) of macrophages is an iron-rich environment (24), so expression of iron uptake genes would be limited and of no significance in modulating pathogenesis.

The range of epinephrine and norepinephrine concentrations used in this study reflect those widely used in other studies (28, 36, 43, 60). Up to half the norepinephrine in the body may be produced in the enteric nervous system (ENS) (3), but the actual concentrations found are very difficult to determine accurately. Furthermore, the levels vary according to, for example, the tissue location, stress levels, and circadian rhythms and can potentially reach millimolar concentrations (12), adding physiological relevance to the concentrations used in this study.

The genes identified in this work show no overlap with genes previously identified as being regulated by epinephrine in S. Typhimurium (36). This may be due to following differences in the screening methods utilized: MudJ transcriptional fusions compared to mRNA levels, differences in growth conditions affecting bacterial physiology, and agar plates compared to LB liquid culture. The two methods may highlight important differences in the S. Typhimurium responses to epinephrine/norepinephrine under different growth conditions. It must be noted that concomitant with our data, Bearson et al. (9) identified the gene iroC as being downregulated by norepinephrine in SAPI-serum minimal media.

The bacterial phenotypes associated with epinephrine/norepinephrine have been linked to effects on iron uptake or interaction with quorum-sensing (QS) systems (13, 43, 60). We have found that the adrenergic regulation of the identified genes is independent of TonB-dependent siderophore transport. Interaction of stress hormones with quorum-sensing systems is thought to be distinct from iron uptake, but the divide between iron uptake and quorum sensing is becoming increasingly blurred. For example, the Pseudomonas aeruginosa siderophore pyoverdine also has a separate role in cell signaling (41), and the Pseudomonas signaling molecule PQS along with other quinolones can chelate iron and facilitate iron uptake (21). A mutant in tonB, essential for iron-bound siderophore uptake, has been reported to be defective in the production of the QS molecule 3-oxo-C12-AHL in Pseudomonas (1). Stress hormone-regulated effects on bacteria are likely to be complex, involving multiple factors, including quorum sensing and iron uptake.

It is interesting to note that three of the identified genes, virK, mig14, and iroC, are all part of a 45-kb S. enterica-specific genomic region, thought to have been acquired by horizontal transfer after divergence from E. coli (7). Both mig14 and virK are found in some (but not all) S. enterica serovars, but neither is found in E. coli. The iro locus is found in S. enterica and some uropathogenic E. coli strains (33, 61). The adrenergic regulation of these genes may therefore form part of a unique Salmonella-specific or even Salmonella serovar-specific response to host-derived hormones.

None of the remaining genes that we identified that are present in E. coli are regulated by epinephrine or norepinephrine in E. coli, to the best of our knowledge, although several microarray studies have been conducted to investigate the global effects of these hormones in E. coli (5, 22, 39). This may be due to the differences in pathogeneses of the two; S. Typhimurium is an invasive pathogen infecting macrophages and epithelial cells, whereas E. coli is mainly noninvasive, remaining in the host intestine. The two very different niches occupied by each pathogen require different sets of genes to be expressed to gain the maximum advantage, so epinephrine and norepinephrine may regulate different sets of genes to the advantage or detriment of the pathogen.

In conclusion, we have identified epinephrine/norepinephrine-mediated downregulation of two important virulence-related genes, virK and mig14, and increased sensitivity to the antimicrobial peptide LL-37, potentially highlighting a mechanism for neuroendocrine stress hormone-mediated downregulation of bacterial virulence.

This study has further elucidated the S. Typhimurium response to the host-derived hormones epinephrine and norepinephrine, providing further insights into the area of bacterium-host communication.

Acknowledgments

We thank Judith Hall and Claire Townes for providing LL-37 and Joe Gray (Pinnacle) for DNA sequencing.

This work was supported by research grants from the Medical Research Council (MRC) and the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC) to C.M.A.K. and P.W. In addition, H.S. was a recipient of a BBSRC DTA Ph.D. studentship with C.M.A.K.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 20 November 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abbas, A., C. Adams, N. Scully, J. Glennon, and F. O'Gara. 2007. A role for TonB1 in biofilm formation and quorum sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 274:269-278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahmer, B. M., J. van Reeuwijk, C. D. Timmers, P. J. Valentine, and F. Heffron. 1998. Salmonella typhimurium encodes an SdiA homolog, a putative quorum sensor of the LuxR family, that regulates genes on the virulence plasmid. J. Bacteriol. 180:1185-1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aneman, A., G. Eisenhofer, L. Olbe, J. Dalenback, P. Nitescu, L. Fandriks, and P. Friberg. 1996. Sympathetic discharge to mesenteric organs and the liver. Evidence for substantial mesenteric organ norepinephrine spillover. J. Clin. Invest. 97:1640-1646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bals, R., X. Wang, M. Zasloff, and J. M. Wilson. 1998. The peptide antibiotic LL-37/hCAP-18 is expressed in epithelia of the human lung where it has broad antimicrobial activity at the airway surface. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95:9541-9546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bansal, T., D. Englert, J. Lee, M. Hegde, T. K. Wood, and A. Jayaraman. 2007. Differential effects of epinephrine, norepinephrine, and indole on Escherichia coli O157:H7 chemotaxis, colonization, and gene expression. Infect. Immun. 75:4597-4607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bassler, B. L., and R. Losick. 2006. Bacterially speaking. Cell 125:237-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bäumler, A. J., and F. Heffron. 1998. Mosaic structure of the smpB-nrdE intergenic region of Salmonella enterica. J. Bacteriol. 180:2220-2223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bearson, B. L., and S. M. D. Bearson. 2008. The role of the QseC quorum-sensing sensor kinase in colonization and norepinephrine-enhanced motility of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Microb. Pathog. 44:271-278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bearson, B. L., S. M. D. Bearson, J. J. Uthe, S. E. Dowd, J. O. Houghton, I. Lee, M. J. Toscano, and D. C. Lay, Jr. 2008. Iron regulated genes of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium in response to norepinephrine and the requirement of fepDGC for norepinephrine-enhanced growth. Microbes Infect. 10:807-816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brodsky, I. E., R. K. Ernst, S. I. Miller, and S. Falkow. 2002. mig-14 is a Salmonella gene that plays a role in bacterial resistance to antimicrobial peptides. J. Bacteriol. 184:3203-3213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brodsky, I. E., N. Ghori, S. Falkow, and D. Monack. 2005. Mig-14 is an inner membrane-associated protein that promotes Salmonella typhimurium resistance to CRAMP, survival within activated macrophages and persistent infection. Mol. Microbiol. 55:954-972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown, S. W., R. T. Meyers, K. M. Brennan, J. M. Rumble, N. Narasimhachari, E. F. Perozzi, J. J. Ryan, J. K. Stewart, and K. Fischer-Stenger. 2003. Catecholamines in a macrophage cell line. J. Neuroimmunol. 135:47-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burton, C. L., S. R. Chhabra, S. Swift, T. J. Baldwin, H. Withers, S. J. Hill, and P. Williams. 2002. The growth response of Escherichia coli to neurotransmitters and related catecholamine drugs requires a functional enterobactin biosynthesis and uptake system. Infect. Immun. 70:5913-5923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clarke, M. B., D. T. Hughes, C. Zhu, E. C. Boedeker, and V. Sperandio. 2006. The QseC sensor kinase: a bacterial adrenergic receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:10420-10425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cogan, T. A., A. O. Thomas, L. E. N. Rees, A. H. Taylor, M. A. Jepson, P. H. Williams, J. Ketley, and T. J. Humphrey. 2007. Norepinephrine increases the pathogenic potential of Campylobacter jejuni. Gut 56:1060-1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cronan, J. E., Jr., and G. L. Waldrop. 2002. Multi-subunit acetyl-CoA carboxylases. Prog. Lipid Res. 41:407-435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crouch, M.-L. V., M. Castor, J. E. Karlinsey, T. Kalhorn, and F. C. Fang. 2008. Biosynthesis and IroC-dependent export of the siderophore salmochelin are essential for virulence of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Mol. Microbiol. 67:971-983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Datsenko, K. A., and B. L. Wanner. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:6640-6645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davis, R. W., D. Botstein, and J. R. Roth. 1980. Advanced bacterial genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 20.Detweiler, C. S., D. M. Monack, I. E. Brodsky, H. Mathew, and S. Falkow. 2003. virK, somA and rcsC are important for systemic Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium infection and cationic peptide resistance. Mol. Microbiol. 48:385-400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Diggle, S. P., S. Matthijs, V. J. Wright, M. P. Fletcher, S. R. Chhabra, I. L. Lamont, X. Kong, R. C. Hider, P. Cornelis, M. Camara, and P. Williams. 2007. The Pseudomonas aeruginosa 4-quinolone signal molecules HHQ and PQS play multifunctional roles in quorum sensing and iron entrapment. Chem. Biol. 14:87-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dowd, S. E. 2007. Escherichia coli O157:H7 gene expression in the presence of catecholamine norepinephrine. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 273:214-223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dreau, D., G. Sonnenfeld, N. Fowler, D. S. Morton, and M. Lyte. 1999. Effects of social conflict on immune responses and E. coli growth within closed chambers in mice. Physiol. Behav. 67:133-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eriksson, S., S. Lucchini, A. Thompson, M. Rhen, and J. C. D. Hinton. 2003. Unravelling the biology of macrophage infection by gene expression profiling of intracellular Salmonella enterica. Mol. Microbiol. 47:103-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fischbach, M. A., H. Lin, L. Zhou, Y. Yu, R. J. Abergel, D. R. Liu, K. N. Raymond, B. L. Wanner, R. K. Strong, C. T. Walsh, A. Aderem, and K. D. Smith. 2006. The pathogen-associated iroA gene cluster mediates bacterial evasion of lipocalin 2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:16502-16507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Flierl, M. A., D. Rittirsch, B. A. Nadeau, A. J. Chen, J. V. Sarma, F. S. Zetoune, S. R. McGuire, R. P. List, D. E. Day, L. M. Hoesel, H. Gao, N. Van Rooijen, M. S. Huber-Lang, R. R. Neubig, and P. A. Ward. 2007. Phagocyte-derived catecholamines enhance acute inflammatory injury. Nature 449:721-725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Freestone, P. P. E., R. D. Haigh, and M. Lyte. 2007. Blockade of catecholamine-induced growth by adrenergic and dopaminergic receptor antagonists in Escherichia coli O157:H7, Salmonella enterica and Yersinia enterocolitica. BMC Microbiol. 7:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Freestone, P. P. E., R. D. Haigh, P. H. Williams, and M. Lyte. 2003. Involvement of enterobactin in norepinephrine-mediated iron supply from transferrin to enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 222:39-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Freestone, P. P. E., and M. Lyte. 2008. Microbial endocrinology: experimental design issues in the study of interkingdom signalling in infectious disease. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 64:75-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goetz, D. H., M. A. Holmes, N. Borregaard, M. E. Bluhm, K. N. Raymond, and R. K. Strong. 2002. The neutrophil lipocalin NGAL is a bacteriostatic agent that interferes with siderophore-mediated iron acquisition. Mol. Cell 10:1033-1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goldberg, A. D., L. C. Becker, R. Bonsall, J. D. Cohen, M. W. Ketterer, P. G. Kaufman, D. S. Krantz, K. C. Light, R. P. McMahon, T. Noreuil, C. J. Pepine, J. Raczynski, P. H. Stone, D. Strother, H. Taylor, and D. S. Sheps. 1996. Ischemic, hemodynamic, and neurohormonal responses to mental and exercise stress. Experience from the Psychophysiological Investigations of Myocardial Ischemia Study (PIMI). Circulation 94:2402-2409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Groves, A. C., J. Griffiths, F. Leung, and R. N. Meek. 1973. Plasma catecholamines in patients with serious postoperative infection. Ann. Surg. 178:102-107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hantke, K., G. Nicholson, W. Rabsch, and G. Winkelmann. 2003. Salmochelins, siderophores of Salmonella enterica and uropathogenic Escherichia coli strains, are recognized by the outer membrane receptor IroN. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:3677-3682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hoiseth, S. K., and B. A. Stocker. 1981. Aromatic-dependent Salmonella typhimurium are non-virulent and effective as live vaccines. Nature 291:238-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hughes, K. T., and J. R. Roth. 1988. Transitory cis complementation: a method for providing transposition functions to defective transposons. Genetics 119:9-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Karavolos, M. H., H. Spencer, D. M. Bulmer, A. Thompson, K. Winzer, P. Williams, J. C. Hinton, and C. M. Khan. 2008. Adrenaline modulates the global transcriptional profile of Salmonella revealing a role in the antimicrobial peptide and oxidative stress resistance responses. BMC Genomics 6:458-471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kawasaki, K., R. K. Ernst, and S. I. Miller. 2004. 3-O-deacylation of lipid A by PagL, a PhoP/PhoQ-regulated deacylase of Salmonella typhimurium, modulates signaling through Toll-like receptor 4. J. Biol. Chem. 279:20044-20048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kawasaki, K., R. K. Ernst, and S. I. Miller. 2005. Inhibition of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium lipopolysaccharide deacylation by aminoarabinose membrane modification. J. Bacteriol. 187:2448-2457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kendall, M. M., D. A. Rasko, and V. Sperandio. 2007. Global effects of the cell-to-cell signaling molecules autoinducer-2, autoinducer-3, and epinephrine in a luxS mutant of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 75:4875-4884. [Author's correction, 76:1319, 2008.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Konopka, K., and J. B. Neilands. 1984. Effect of serum albumin on siderophore-mediated utilization of transferrin iron. Biochemistry 23:2122-2127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lamont, I. L., P. A. Beare, U. Ochsner, A. I. Vasil, and M. L. Vasil. 2002. Siderophore-mediated signaling regulates virulence factor production in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99:7072-7077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lyte, M. 2004. Microbial endocrinology and infectious disease in the 21st century. Trends Microbiol. 12:14-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lyte, M., and S. Ernst. 1992. Catecholamine induced growth of gram negative bacteria. Life Sci. 50:203-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McCuddin, Z. P., S. A. Carlson, and V. K. Sharma. 2008. Experimental reproduction of bovine Salmonella encephalopathy using a norepinephrine-based stress model. Vet. J. 175:82-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McHugh, J. P., F. Rodriguez-Quinones, H. Abdul-Tehrani, D. A. Svistunenko, R. K. Poole, C. E. Cooper, and S. C. Andrews. 2003. Global iron-dependent gene regulation in Escherichia coli. A new mechanism for iron homeostasis. J. Biol. Chem. 278:29478-29486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Merighi, M., A. N. Septer, A. Carroll-Portillo, A. Bhatiya, S. Porwollik, M. McClelland, and J. S. Gunn. 2009. Genome-wide analysis of the PreA/PreB (QseB/QseC) regulon of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. BMC Microbiol. 9:42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Methner, U., W. Rabsch, R. Reissbrodt, and P. H. Williams. 2008. Effect of norepinephrine on colonisation and systemic spread of Salmonella enterica in infected animals: role of catecholate siderophore precursors and degradation products. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 298:429-439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Miller, J. H. 1992. A short course in bacterial genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 49.Miller, S. I., R. K. Ernst, and M. W. Bader. 2005. LPS, TLR4 and infectious disease diversity. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3:36-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Monje-Casas, F., J. Jurado, M. J. Prieto-Alamo, A. Holmgren, and C. Pueyo. 2001. Expression analysis of the nrdHIEF operon from Escherichia coli. Conditions that trigger the transcript level in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 276:18031-18037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nakano, M., A. Takahashi, Y. Sakai, and Y. Nakaya. 2007. Modulation of pathogenicity with norepinephrine related to the type III secretion system of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. J. Infect. Dis. 195:1353-1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nordlund, P., and P. Reichard. 2006. Ribonucleotide reductases. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 75:681-706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Overhage, J., A. Campisano, M. Bains, E. C. W. Torfs, B. H. A. Rehm, and R. E. W. Hancock. 2008. Human host defense peptide LL-37 prevents bacterial biofilm formation. Infect. Immun. 76:4176-4182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Papezova, K., D. Gregorova, J. Jonuschies, and I. Rychlik. 2007. Ordered expression of virulence genes in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Folia Microbiol. 52:107-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rasko, D. A., C. G. Moreira, D. R. Li, N. C. Reading, J. M. Ritchie, M. K. Waldor, N. Williams, R. Taussig, S. Wei, M. Roth, D. T. Hughes, J. F. Huntley, M. W. Fina, J. R. Falck, and V. Sperandio. 2008. Targeting QseC signaling and virulence for antibiotic development. Science 321:1078-1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Reading, N. C., D. A. Rasko, A. G. Torres, and V. Sperandio. 2009. The two-component system QseEF and the membrane protein QseG link adrenergic and stress sensing to bacterial pathogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:5889-5894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Reading, N. C., A. G. Torres, M. M. Kendall, D. T. Hughes, K. Yamamoto, and V. Sperandio. 2007. A novel two-component signaling system that activates transcription of an enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli effector involved in remodeling of host actin. J. Bacteriol. 189:2468-2476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 59.Scheckelhoff, M. R., S. R. Telford, M. Wesley, and L. T. Hu. 2007. Borrelia burgdorferi intercepts host hormonal signals to regulate expression of outer surface protein A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:7247-7252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sperandio, V., A. G. Torres, B. Jarvis, J. P. Nataro, and J. B. Kaper. 2003. Bacteria-host communication: the language of hormones. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:8951-8956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Valdivia, R. H., D. M. Cirillo, A. K. Lee, D. M. Bouley, and S. Falkow. 2000. mig-14 is a horizontally acquired, host-induced gene required for Salmonella enterica lethal infection in the murine model of typhoid fever. Infect. Immun. 68:7126-7131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Van Immerseel, F., J. De Buck, F. Pasmans, P. Velge, E. Bottreau, V. Fieves, F. Haesebrouck, and R. Ducatelle. 2003. Invasion of Salmonella enteritidis in avian intestinal epithelial cells in vitro is influenced by short-chain fatty acids. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 85:237-248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vlisidou, I., M. Lyte, P. M. van Diemen, P. Hawes, P. Monaghan, T. S. Wallis, and M. P. Stevens. 2004. The neuroendocrine stress hormone norepinephrine augments Escherichia coli O157:H7-induced enteritis and adherence in a bovine ligated ileal loop model of infection. Infect. Immun. 72:5446-5451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Williams, P. 2007. Quorum sensing, communication and cross-kingdom signalling in the bacterial world. Microbiology 153:3923-3938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Williams, P. H., W. Rabsch, U. Methner, W. Voigt, H. Tschape, and R. Reissbrodt. 2006. Catecholate receptor proteins in Salmonella enterica: role in virulence and implications for vaccine development. Vaccine 24:3840-3844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]