Abstract

Micrococcus luteus (NCTC2665, “Fleming strain”) has one of the smallest genomes of free-living actinobacteria sequenced to date, comprising a single circular chromosome of 2,501,097 bp (G+C content, 73%) predicted to encode 2,403 proteins. The genome shows extensive synteny with that of the closely related organism, Kocuria rhizophila, from which it was taxonomically separated relatively recently. Despite its small size, the genome harbors 73 insertion sequence (IS) elements, almost all of which are closely related to elements found in other actinobacteria. An IS element is inserted into the rrs gene of one of only two rrn operons found in M. luteus. The genome encodes only four sigma factors and 14 response regulators, a finding indicative of adaptation to a rather strict ecological niche (mammalian skin). The high sensitivity of M. luteus to β-lactam antibiotics may result from the presence of a reduced set of penicillin-binding proteins and the absence of a wblC gene, which plays an important role in the antibiotic resistance in other actinobacteria. Consistent with the restricted range of compounds it can use as a sole source of carbon for energy and growth, M. luteus has a minimal complement of genes concerned with carbohydrate transport and metabolism and its inability to utilize glucose as a sole carbon source may be due to the apparent absence of a gene encoding glucokinase. Uniquely among characterized bacteria, M. luteus appears to be able to metabolize glycogen only via trehalose and to make trehalose only via glycogen. It has very few genes associated with secondary metabolism. In contrast to most other actinobacteria, M. luteus encodes only one resuscitation-promoting factor (Rpf) required for emergence from dormancy, and its complement of other dormancy-related proteins is also much reduced. M. luteus is capable of long-chain alkene biosynthesis, which is of interest for advanced biofuel production; a three-gene cluster essential for this metabolism has been identified in the genome.

Micrococcus luteus, the type species of the genus Micrococcus (family Micrococcaceae, order Actinomycetales) (117), is an obligate aerobe. Three biovars have been distinguished (138). Its simple, coccoid morphology delayed the recognition of its relationship to actinomycetes, which are typically morphologically more complex. In the currently accepted phylogenetic tree of the actinobacteria, Micrococcus clusters with Arthrobacter and Renibacterium. Some other coccoid actinobacteria originally also called Micrococcus, but reclassified into four new genera (Kocuria, Nesterenkonia, Kytococcus, and Dermacoccus), are more distant relatives (121). The genus Micrococcus now includes only five species: M. luteus, M. lylae, M. antarcticus, M. endophyticus, and M. flavus (20, 69, 70, 121).

We report here the genome sequence of Micrococcus luteus NCTC2665 (DSM 20030T), a strain of historical interest, since Fleming used it to demonstrate bacteriolytic activity (due to lysozyme) in a variety of body tissues and secretions (29, 30), leading to its designation as Micrococcus lysodeikticus until its taxonomic status was clarified in 1972 (59). M. luteus has been used in a number of scientific contexts. The ease with which its cell wall could be removed made it a favored source of bacterial cell membranes and protoplasts for investigations in bioenergetics (28, 34, 89, 93). Because of the exceptionally high GC content of its DNA, M. luteus was used to investigate the relationship between codon usage and tRNA representation in bacterial genomes (51, 52, 61). Although it does not form endospores, M. luteus can enter a profoundly dormant state, which could explain why it may routinely be isolated from amber (39). Dormancy has been convincingly demonstrated under laboratory conditions (53-55, 83), and a secreted protein (Rpf) with muralytic activity is involved in the process of resuscitation (81, 82, 84, 85, 87, 125, 133).

Micrococci are also of biotechnological interest. In addition to the extensive exploitation of these and related organisms by the pharmaceutical industry for testing and assaying compounds for antibacterial activity, micrococci can synthesize long-chain alkenes (1, 2, 127). They are also potentially useful for ore dressing and bioremediation applications, since they are able to concentrate heavy metals from low-grade ores (26, 66, 67, 116).

Given its intrinsic historical and biological importance, and its biotechnological potential, it is perhaps surprising that the genome sequence of M. luteus was not determined previously (130). We consider here the strikingly small genome sequence in these contexts and also in relation to the morphological simplicity of M. luteus compared to many of its actinobacterial relatives, which include important pathogens as well as developmentally complex, antibiotic-producing bacteria with some of the largest bacterial genomes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Genome sequencing, assembly, and gap closure.

The genome of M. luteus was sequenced at the Joint Genome Institute (JGI) by using a combination of 8-kb and fosmid (40-kb) libraries and 454 pyrosequencing. All general aspects of library construction and sequencing performed at the JGI can be found at http://www.jgi.doe.gov/. Pyrosequencing reads were assembled by using Newbler assembler (Roche http://www.454.com/downloads/protocols/1_paired_end.pdf). Large Newbler contigs were chopped into 2,793 overlapping fragments of 1,000 bp and entered into assembly as pseudoreads. The sequences were assigned quality scores based on Newbler consensus q-scores with modifications to account for overlap redundancy and adjust-inflated q-scores. Hybrid 454/Sanger assembly was performed with Arachne assembler (8). Possible mis-assemblies were corrected and gaps between contigs were closed by custom primer walks from subclones or PCR products. The error rate of the completed genome sequence of M. luteus is less than 1 in 50,000.

Genome annotation was performed with the Integrated Microbial Genomes Expert Review (IMG-ER) annotation pipeline (72). Predicted coding sequences (CDSs) were additionally manually evaluated by using JGI's Quality Assurance pipeline (http://geneprimp.jgi-psf.org/).

Genome analysis.

Comparative analysis of M. luteus with related organisms was performed mainly using a set of tools available in IMG. The cutoff for the minimal size of an open reading frame (ORF) was set to 30 residues. Unique and homologous M. luteus genes were identified by using BLASTp (cutoff scores of E < 10−2). Reciprocal hits were calculated based on these values. Comparisons between genes for the identification of common genes were conducted using BLAST similarities of e value 10−5 and similarity > 20% (3). For the determination of orthologs in selected other genomes, BLASTp (3) was used with an expect value threshold of 1e−4. Two proteins were considered orthologous only if they were reciprocal best hits of each other in BLAST databases consisting of all proteins encoded by their respective genomes. In some situations where detailed “manual” evaluation was made, apparent orthologs which showed less than 50% amino acid identity or covered less than 80% of the longer protein were flagged as doubtful and rejected unless they were part of a syntenous segment. Signal peptides were identified by using SignalP 3.0 (10) and TMHMM (62) at default values.

Following automated annotation of the completed genome sequence, a workshop was held in Jerusalem (13 to 18 April 2008), as part of the IMG expert review process, to compare M. luteus with other closely related actinobacteria and illuminate its relationship to Arthrobacter and Kocuria rhizophila (formerly Sarcina lutea) (123), which are two of its closest relatives. Comparative genomic studies were performed in the context of the Integrated Microbial Genomes system (IMG), v.2.2 (73). Habitat information was retrieved from the Genomes On Line Database (GOLD) (68).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The sequence data described here have been deposited in GenBank (NC_012803) and GOLD (accession number Gc01033).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

General features and architecture of the genome.

The genome consists of one circular chromosome of 2,501,097 bp with a 73% GC content. It is one of the smallest actinobacterial genomes sequenced to date. The origin of replication was identified in a region upstream of dnaA, where a significant shift in the GC skew value was observed (Fig. 1). In common with K. rhizophila, there is no evidence of the global GC skew (preference for G on the leading strand) that is commonly observed in many other bacterial genomes, including those of some of its close relatives, including Arthrobacter aurescens and Renibacterium salmoninarum (78, 123, 137). Of 2,458 predicted genes, 2,403 encode proteins. Putative functions were assigned to 74.2% of genes, while the remaining 25.8% were annotated as hypothetical proteins. The ATG start codon is used most frequently (1,718 times), followed by GTG and TTG (665 and 20 times, respectively). There is an even stronger bias to the use of TGA as stop codon (2,238 times), with TAG and TAA being used only 115 and 50 times, respectively.

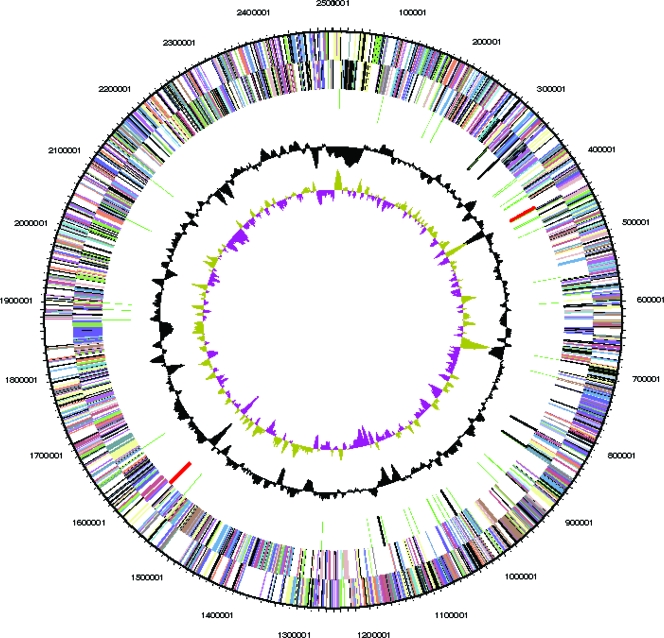

FIG. 1.

Circular representation of the M. luteus chromosome. Genome coordinates are given in Mbp. From outside to inside, the various circles represent genes on the forward strand, genes on the reverse strand, RNA genes (tRNAs green, rRNAs red, other RNAs black), GC content, and GC skew. Genes are color coded according to their COG category. The color code of function category for top COG hit is shown in Table S4 in the supplemental material.

The properties and statistics of the M. luteus genome are summarized in Table 1. There are two rRNA operons with the typical order of 16S, 23S, and 5S RNA genes. However, in one of them, the rrs gene, Mlut_14290, encoding the 16S rRNA, is interrupted by an ISL3 family transposase (see below). The other rrs gene, Mlut_03860, has an additional “A” residue at position 1437 that is absent in Mlut_14290. A BLAST search of the nucleotide database with Mlut_03860 showed that of the top 100 hits (classified as M. luteus, Micrococcus sp., or uncultured bacterium) 95 clearly do not have the A at position 1437. The transposon insertion has therefore inactivated the rrs gene that mostly closely resembles that of the species. Possibly, the presence of both functional rrs genes was detrimental to the functionality of the ribosome and the transposon insertion in Mlut_14290 rescued fitness. Forty-eight tRNA genes were identified encoding tRNAs theoretically capable of translating all codons including AGA, which had previously been found to be untranslatable using an in vitro system derived from a M. luteus strain (61). Eighteen additional RNA genes were predicted by using models from the RNA families database (Rfam) (40). The substantially reduced number of paralogous genes present (9.2%) compared to Arthrobacter spp. (57.6% for Arthrobacter aurescens TC1 and 61.3% for Arthrobacter sp. strain FB24) correlates with the reduced size of the M. luteus genome. This indicates that most of the gene reduction or expansion that postdates the last common ancestor of Micrococcus and Arthrobacter has affected paralogous gene families.

TABLE 1.

Genome statistics for members of the Micrococcaceae

| Characteristic | Organism |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Micrococcus luteus | Kocuria rhizophila | Arthrobacter aurescens TC1 | Arthrobacter sp. strain FB24 | Renibacterium salmoninarum | |

| Genome size in bp | 2,501,097 | 2,697,540 | 5,226,648 | 5,070,478 | 3,155,210 |

| Coding region size in bp (%) | 2,296,689 (91.8) | 2,408,673 (89.29) | 4,705,572 (90) | 4,573,776 (90.2) | 2,863,187 (90.7) |

| G+C content (%) | 73 | 71 | 62 | 65 | 56 |

| No. (%) of: | |||||

| Plasmids | 0a | 0 | 2 | 3 | 0 |

| Total genes | 2,348 | 2,413 | 4,793 | 4,622 | 3,558 |

| RNA genes | 60 (2.6) | 56 (2.4) | 94 (2.0%) | 86 (1.9) | 51 (1.4) |

| Protein-coding genes | 2,288 (97.4) | 2,357 (97.7) | 4,699 (98.0) | 4,536 (98.1) | 3,507 (98.6) |

| Genes with function | 1,742 (74.2) | 1,478 (61.3) | 3,419 (71.33) | 3,279 (70.9) | 2,679 (75.3) |

| Genes in ortholog clusters | 4,316 (90.4) | 4,216 (91.5) | |||

| Genes in paralog clusters | 217 (9.2) | 967 (40.1) | 2,749 (57.6) | 2,824 (61.3) | |

| Genes assigned to COGs | 1,717 (73.1) | 1,799 (74.6) | 3,307 (69.0) | 3,361 (72.7) | 2,389 (67.1) |

| Genes assigned to Pfam | 1,731 (73.7) | 1,822 (75.5) | 3,525 (73.5) | 3,426 (74.1) | 2,478 (69.7) |

| Genes with signal peptides | 487 (20.7) | 653 (27.1) | 1,442 (30.1) | 1,454 (31.5) | 1,030 (29.0) |

| Genes with transmembrane helices | 543 (23.1) | 569 (23.6) | 1,187 (24.9) | 1,168 (25.3) | 836 (23.5) |

| Fused genes | 195 (8.3) | 135 (5.6) | 292 (6.1) | 320 (6.9) | 125 (3.5) |

Although a plasmid denoted pMLU1 has previously been reported from the NCTC 2665 strain of M. luteus(81), there was no evidence of it in the DNA provided for the genome sequencing project.

Genes found in a 0.9-Mbp segment, including the presumed origin of replication, show no particular strand bias, whereas genes located in the remainder of the genome (0.5 to 2.1 Mbp) are more abundant on the presumed leading strand (Fig. 1). RNA genes are more abundant on one chromosome arm (0 to 1.25 Mbp) than on the other (1.25 to 2.5 Mbp).

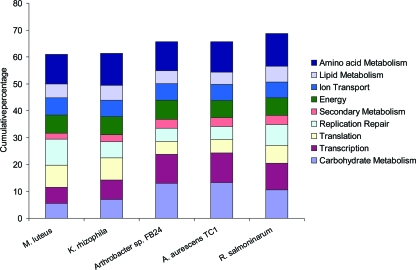

In order to evaluate the functional content of the genomes of various members of the Micrococcaceae, the numbers of genes assigned to different COG functional categories are compared in Table 2 and Fig. 2. Generally speaking, the relative proportions of genes in different functional categories are in line with expectation, based on its small genome size, as described previously (60). M. luteus devotes a greater proportion of its genome to core processes of translation, replication, and repair than do the other members of the Micrococcaceae except K. rhizophila, which has a reduced complement of genes concerned with replication and repair. On the other hand, Arthrobacter spp. and Renibacterium salmoninarum devote a greater proportion of their genomes (between 10 and 11%) to transcription and its regulation than do either M. luteus or K. rhizophila (6% and 7%, respectively) and have a greater repertoire of sigma factors and associated regulatory proteins. Other prominent differences are the reduced number and proportion of genes concerned with carbohydrate metabolism in M. luteus (and K. rhizophila) compared to other members of the Micrococcaceae and also the presence of a very large number of genes encoding transposases in the M. luteus genome (see below). In line with their small genome sizes, both M. luteus and K. rhizophila have fewer genes concerned with secondary metabolism than R. salmoninarum and the two Arthrobacter spp. Genes within the other COG functional categories shown in Table 2 (amino acid metabolism, lipid metabolism, energy production, and ion transport) increase in number in proportion to genome size.

TABLE 2.

Genes in selected COG functional categories

| Organism | No. of COG Genes | No. (%) of genes involved in: |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amino acid metabolism | Carbohydrate metabolism | Energy | Ion transport | Lipid metabolism | Replication repair | Secondary metabolism | Transcription | Translation | ||

| Micrococcus luteus (Fleming) NCTC 2665 | 1,768 | 195 (11.0) | 97 (5.5) | 118 (6.7) | 113 (6.4) | 92 (5.2) | 172 (9.7) | 39 (2.2) | 106 (6.0) | 147 (8.3) |

| Kocuria rhizophila DC2201 | 1,799 | 212 (11.8) | 125 (7.0) | 123 (6.8) | 110 (6.1) | 101 (5.6) | 107 (6.0) | 44 (2.5) | 129 (7.2) | 150 (8.3) |

| Arthrobacter aurescens TC1 | 3,307 | 370 (11.2) | 441 (13.3) | 213 (6.4) | 198 (6.0) | 153 (4.6) | 157 (4.8) | 108 (3.3) | 364 (11.0) | 165 (5.0) |

| Arthrobacter sp. strain FB24 | 3,361 | 364 (10.8) | 436 (13.0) | 239 (7.1) | 208 (6.2) | 157 (4.7) | 164 (4.9) | 112 (3.3) | 363 (10.8) | 162 (4.8) |

| Renibacterium salmoninarum ATCC 33209 | 2,389 | 288 (12.1) | 250 (10.5) | 155 (6.5) | 142 (5.9) | 141 (5.9) | 183 (7.7) | 84 (3.5) | 238 (10.0) | 158 (6.6) |

FIG. 2.

Percentage of genes assigned to different COG categories in M. luteus and related organisms.

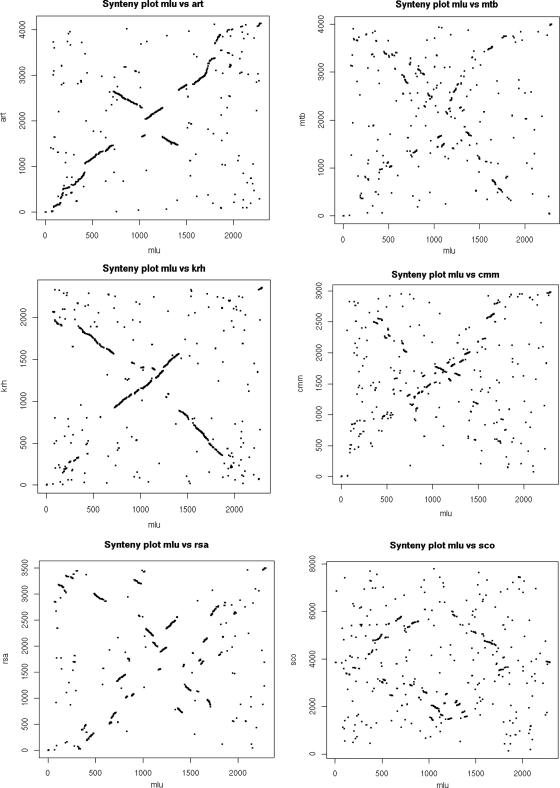

Dot plots comparing the positions of genes in M. luteus with their putative orthologs in other actinobacteria reveal extensive synteny with other members of the Micrococcaceae, with evidence for one and two inversions about the presumed replication origins in the comparisons with K. rhizophila and Arthrobacter sp. strain FB24, respectively (Fig. 3). Synteny, although interrupted by many more inversions about the origin, was also evident with more distantly related organisms, such as Clavibacter michiganensis, Renibacterium salmoninarum, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and even with Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2), despite the linearity and ∼3-fold larger size of this streptomycete genome (11).

FIG. 3.

Synteny between actinobacterial genomes. For each genome the first gene is dnaA, except in the case of the linear S. coelicolor genome, in which dnaA is located centrally. Each dot represents a reciprocal best match (BLASTp) between proteins in the genomes being compared. Dots are positioned according to their genome locations. See Materials and Methods for further details. Abbreviations: Mlu, Micrococcus luteus; Krh, Kocuria rhizophila (123); Art, Arthrobacter sp. strain FB24; Cmm, Clavibacter michiganensis subsp. michiganensis (32); Mtb, Mycobacterium tuberculosis (22); Sco, Streptomyces coelicolor (11); Rsa, Renibacterium salmoninarum (137).

TTA-containing genes are exceptionally rare in M. luteus.

The high G+C content of actinobacterial genomes is correlated with a paucity of A+T-rich codons. This is particularly marked for the TTA codon, one of six encoding leucine, to the extent that in streptomycetes the codon is found only in genes that are nonessential for growth. For example, S. coelicolor has only 145 TTA-containing genes, and the determinant for the cognate tRNA can be deleted without impairing vegetative growth. It has been proposed that the translation of UUA-containing mRNA is subject to checkpoint control by regulation of the availability of charged cognate tRNA (130). Remarkably, an even smaller proportion of M. luteus genes, just 24 of 2,403, contain a TTA codon. It would be of considerable interest to find out whether the elimination of the relevant tRNA determinant has any phenotypic consequences.

Mobile genetic elements.

Although M. luteus has one of the smallest actinobacterial genomes, it harbors more than 70 IS elements, or their remnants. Thirty distinct IS elements are present, representing 8 of the 23 well-characterized IS families, i.e., IS3, IS5, IS21, IS30, IS110, IS256, IS481, and ISL3 (Table 3). No elements related to the class II transposon, Tn3, were found. Although the IS3 family elements show the greatest diversity (eight distinct elements are present), only one of them is intact. There are five distinct types of IS256 family elements, most of which (19 of 24 copies) are intact. Some regions contain several elements, including examples of one IS being inserted into another. For example, there are three IS3 elements into which IS256 family members (ISMlu1, ISMlu2, or ISMlu11) have inserted. With only one exception (Burkholderia mallei), all ISMlu transposases have their closest relatives in other actinomycetes, i.e., Brevibacterium linens, Corynebacterium diphtheriae, Corynebacterium jeikeium, Corynebacterium striatum, Leifsonia xyli, Mycobacterium avium, Mycobacterium branderi, Mycobacterium marinum, Mycobacterium smegmatis, Rhodococcus aetherivorans, Rhodococcus erythropolis, S. coelicolor, and Terrabacter sp. One copy of ISMlu4 (ISL3 family) has inserted into one of the two M. luteus rrs genes (Mlut_14290) (see above). There is evidence from Escherichia coli that such insertions are not necessarily polar, so the genes encoding the 23S and 5S rRNA downstream of Mlut_14290 may be expressed (15, 79). Another element, ISMlu9 (IS481 family), is located just downstream of the corresponding 5S rRNA.

TABLE 3.

Distribution of M. luteus IS elements among the different families

| Familya | Chemistryb | No. of distinct elements | Total no. of copies (partial) |

|---|---|---|---|

| IS3 | DDE | 8 | 8 (7) |

| IS5 | DDE | 4 | 12 (0) |

| IS21 | DDE | 1 | 1 (0) |

| IS30 | DDE | 1 | 2 (0) |

| IS110 | DDE? | 1 | 2 (0) |

| IS256 | DDE | 5 | 24 (5) |

| IS481 | DDE | 6 | 7 (4) |

| Total | 31 | 73 (19) |

The various IS families have been described and documented by Mahillon and Chandler (19, 71). IS1, IS4, IS6, IS66, IS91, IS200/IS605, IS607, IS630, IS701, IS982, IS1380, IS1634, ISAs1, ISH3, ISL3, and Tn3 family elements were not found.

Details of the transposase chemistry are given on the ISfinder website (http://www-is.biotoul.fr/).

A complete compilation of the “ISome” of M. luteus is given in the ISfinder database (115). The plethora of IS elements in M. luteus may be responsible, at least in part, for the intraspecies heterogeneity that has been described previously (90, 138).

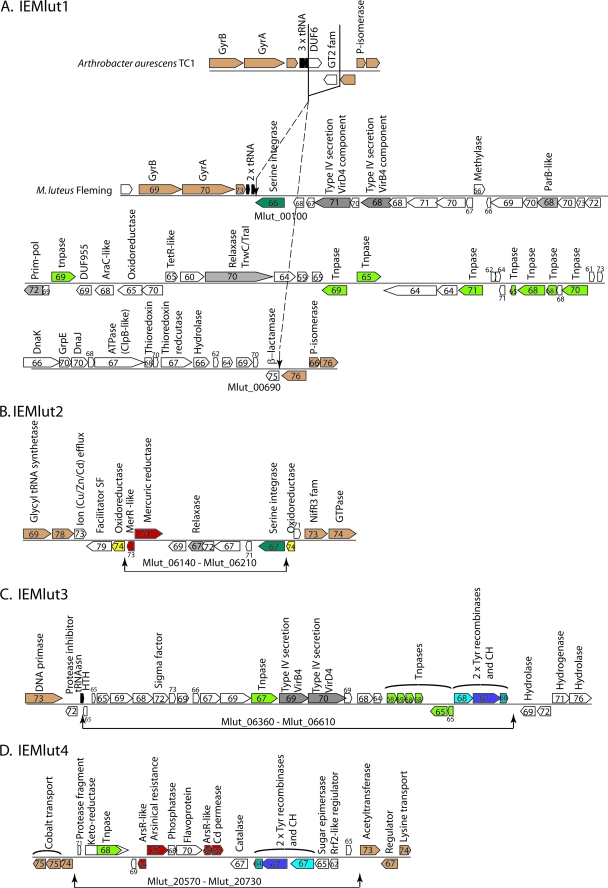

A search for integrated genetic elements associated with integrase/recombinase proteins revealed three serine recombinases, Mlut_16170, Mlut_06210, and Mlut_00100. Mlut_00100 and Mlut_06210 are members of the family of large serine recombinases which are common in the actinomycetes and low-GC% Gram-positive bacteria (118). These recombinases can be phage-encoded or present on integrating conjugative elements (ICEs), where they excise an element from the chromosome to form a circle of DNA that then undergoes conjugation to a new host (16, 88). In the recipient the circular molecule integrates, often site specifically via the action of the recombinase. Mlut_00100 lies at one end of 59 genes, generally of low GC%, that interrupt a region with synteny to Arthrobacter (Fig. 4). This element, IEMlut1, may be conjugative since it carries a putative relaxase and DNA primase that could act to initiate conjugal transfer of an excised circle of DNA. Paralogues of dnaK, grpE, dnaJ, clpB, and thioredoxin metabolism genes encoded on IEMlut1 may have a role in overcoming environmental stress.

FIG. 4.

Proposed integrated elements (IEs) in M. luteus Fleming. Block arrows containing numbers represent ORFs and their %GC values. The proposed function of the gene products is shown where predictions from database searches are informative. All four of the proposed IEs are within regions of lower than average %GC for M. luteus, and three of the elements (IEMlut1, IEMlut2, and IEMlut4) interrupt regions with good synteny with Arthrobacter. The ORFs are colored as follows: brown indicates synteny of gene order with Arthrobacter; gray indicates that the gene product might be involved in plasmid replication or transfer; green is a transposase or fragment thereof; red is used to highlight the putative metal resistance genes. A and B. IEMlut1 (approximate coordinates 11840 to 72798) and IEMlut2 (approximate coordinates 672329 to 680904) may have been integrated via the serine integrases, Mlut_00100 and Mlut_06210, respectively. The putative DnaK, GrpE, and DnaJ and the ClpB-like chaperone genes (Mlut_00560 to Mlut00580, Mlut_00600) have been included in IEMlut1 since they appear to have been acquired horizontally. Their closest relatives are not the paralogous genes on the M. luteus chromosome (Mlut_11810, Mlut_11800, Mlut_11790, and Mlut_18660) but genes from other actinomycetes such as Streptomyces sp., Catenulispora, and Gordonia. On the other hand, the closest relatives of Mlut_11790, Mlut_11800, and Mlut_18660 are from the phylogenetically close Arthrobacter and Kocuria. IEMlut2 appears to have inserted into a putative oxidoreductase to yield two gene fragments, Mlut_06130 and Mlut_06220 (yellow). (C and D) IEMlut3 (approximate coordinates 695571 to 717542) and IEMlut4 (approximate coordinates 2223379 to 2238868) may have integrated via the action of the conserved triplet of genes that includes two tyrosine recombinases (the closest homologues are either purple [Mlut_06600 and Mlut_20690] or light blue [Mlut_06590 and Mlut_20700]) and a conserved hypothetical (CH; colored blue-green) (Mlut_06610 and Mlut_20680).

A second element, IEMlut2, appears to have integrated into a flavin-dependent oxidoreductase represented by the gene fragments Mlut_06220 and Mlut_06130. When these two fragments are spliced together and used to search the protein database, they align well with close homologues, e.g., from Arthrobacter. The large serine recombinase, Mlut_06210, is at one end of this element and is probably responsible for the integration in the ORF. There is a putative relaxase gene, albeit annotated as a pseudogene, suggesting that this element might once have been conjugative. IEMlut2 encodes a putative mercuric reductase and a MerR-like regulator.

IEMlut3 and IEMlut4 were probably mobilized by a conserved gene triplet acting together. An alignment of the XerD homologues (which are members of the tyrosine recombinase family of site-specific recombinases) shows that Mlut_06590 and Mlut_20700 are almost identical, as are Mlut_06600 and Mlut_20690. In addition, Mlut_06610 is 83% identical to Mlut_20680. These six genes therefore represent two examples of a conserved triplet of genes that can also be seen in Mycobacterium sp. strain KMS, M. smegmatis, Arthrobacter, an organism denoted Vibrio angustum S14 in the GOLD (http://genomesonline.org/index2.htm) and others. In M. luteus the triplets are located at each end of two low GC-rich regions, IEMlut3 and IEMlut4 (Fig. 4). IEMlut3 encodes one of the few sigma factors in M. luteus so acquisition of this element may have had a global effect on gene expression. The extent of this element is currently defined only by the lower than average GC% since it lies in a region with little synteny with Arthrobacter. IEMlut4 contains putative arsenic and cadmium resistance determinants (Mlut_20620 and Mlut_20660, respectively).

Two of the four putative integrated elements may therefore have been the vehicles for introducing mercury, arsenic, and cadmium resistance into M. luteus. In addition, Mlut_18330 (a DDE family transposase; no other paralogues in M. luteus) is adjacent to a putative copper resistance protein (68% GC; Mlut_18340), suggesting the possible presence of a small, fifth element within M. luteus.

Regulation and signal transduction.

Detailed analysis of individual genes revealed that only 103 M. luteus genes, i.e., 4.4%, including its four sigma factors (see below), encode likely DNA-interacting regulatory proteins, while 27 others (1.1%) have roles in signal transduction. One might expect that as the genome size approaches some minimal level for a fully functional organism, the proportion of regulatory genes that have orthologs in related genomes of larger size would approach (though not reach) 100%. However, the suite of M. luteus regulatory genes includes many that do not appear to be conserved in the genomes of other members of the Micrococcaceae (K. rhizophila and Arthrobacter sp. strain FB24). To evaluate this more closely, we carried out a limited “manual” analysis of apparent orthologs, based on the relatively stringent criteria of reciprocal BLASTp hits plus at least 50% amino acid identity over at least 80% of the length of the longer protein. On this basis, 69 of the 99 genes (excluding sigma factors) were considered to be orthologous with genes in one or more of the other genomes (see Table S1 in the supplemental material).

Of the four genes likely to encode sigma factors, Mlut_13280 encodes the principal sigma factor (RpoD). It is very similar to the principal sigma factor (HrdB) of S. coelicolor (84% identity over the C-terminal 344 residues; 35% identity over the N-terminal 153 amino acids). The other three appear to encode ECF sigma factors, which are usually involved in responses to extra-cytoplasmic stresses or stimuli. One of these, Mlut_07700, is widely conserved and corresponds to SCO5216 of S. coelicolor, whose product (SigR) plays a key role in responses to disulfide stress. Mlut_07700 is located immediately upstream of an ortholog of rsrA, which in other actinomycetes encodes an anti-sigma that antagonizes SigR. The micrococcal RsrA retains the conserved cysteine residues involved in sensing disulfide stress. Another sigma factor gene, Mlut_06410, is species specific and is located within IEMlut3 (see above and Fig. 4), and the third, Mlut_14900, appears to be present in Arthrobacter and possibly other actinobacteria. The absence of any class III sigma genes (i.e., related to sigma B of Bacillus subtilis) and of any genes encoding the relevant classes of anti-sigmas or anti anti-sigmas is unusual among Gram-positive bacteria. In general, members of that class of sigmas are involved either in nonnutritional stress responses or sporulation. There was no gene identified for a sigma-54: this class of sigmas appears to be confined to Gram-negative bacteria. Since sigma factors underpin nearly all cellular developmental programs in bacteria, the simplicity of the sigma factor profile suggests that there is no undiscovered developmental program in M. luteus and that its range of stress responses may be exceptionally narrow.

The genome encodes 14 response regulators, accounting for an unusually high proportion (14%) of the total suite of regulatory proteins (only ca. 6% of Streptomyces coelicolor regulatory proteins are response regulators). Eleven of them form clear two-component systems with an adjacent gene encoding the cognate histidine kinase, two of which are widely conserved. PhoRP (Mlut_03740 and Mlut_03750) probably respond to phosphate limitation and MtrAB (Mlut_14770 and Mlut_14760) probably play a role in cell cycle progression (but here without the widely conserved adjacent gene lpqB, which appears to play an accessory role in the action of MtrAB in other actinobacteria). In addition, the Mlut_14100 and Mlut_14110 genes are probably involved in the regulation of citrate/malate metabolism, whereas the Mlut_04120-Mlut_04130 gene pair, of unknown function, is present in many simple actinobacteria but absent from S. coelicolor. Three response regulator genes are “orphans” not located very close to genes for histidine protein kinases, while just two of the thirteen genes for histidine protein kinases are located away from any response regulator gene. All but one (Mlut_03350) of the “orphan” response regulators retain the highly conserved aspartate expected to be phosphorylated, as well as other conserved residues in the typical “phosphorylation pocket,” suggesting that their regulation is via phosphorylation. Atypical response regulators that seem unlikely to be regulated by conventional phosphorylation are found in other organisms, e.g., S. coelicolor (45). Among the three orphans, one is widespread among the actinobacteria (Mlut_11030), but there appears to be no information about the functions of the orthologs, at least among streptomycetes. One is confined to the Micrococcineae (Mlut_03350), and one (Mlut_21850) is genome specific.

M. luteus has three pkn genes encoding serine/threonine protein kinases (STPKs): Mlut_00760, Mlut_00750, and Mlut_13750, which correspond to pknA, pknB, and pknL found in M. leprae, C. glutamicum, and M. tuberculosis (which has 11 pkn genes) (6, 22, 23, 96). The three STPK genes (see also below, under cell division, morphogenesis, and peptidoglycan biosynthesis), together with a gene encoding a partial STPK sequence apparently fused to a protein of unknown function, represent ca. 4% of the “regulatory” genome (a similar proportion as in S. coelicolor).

Unusual small iron-sulfur cluster-containing regulatory proteins resembling the archetypal WhiB sporulation protein of streptomycetes (hence the term Wbl, for WhiB-like) have been found in all actinobacteria and in no other bacteria. M. luteus has an unusually small number (two) of them. In general, orthologs of some of these small genes are widely conserved, although their small size makes it difficult to be confident about orthology. One of the two (Mlut_05270) appears to be orthologous with the near-ubiquitous archetypal whiB, which is important not only for development in streptomycetes but also for cell division in mycobacteria (38, 119). The other is similar to wblE, which is also nearly ubiquitous but whose role is less clear, although it has been implicated in the oxidative stress response in corynebacteria (58). The absence of a wblC gene may account for the sensitivity of M. luteus to many antibiotics. In mycobacteria and streptomycetes WblC is a pleiotropic regulator that plays an important role in resistance to diverse antibiotics and other inhibitors (80).

The presence of two crp-like genes (Mlut_09560 and Mlut_18280), and a putative adenylate cyclase gene (Mlut_05920), indicates that cyclic AMP (cAMP) plays a signaling role in M. luteus, as in most other actinobacteria. Mlut_18280 is conserved among other actinobacteria, so it probably plays the major role in sensing cAMP.

The M. luteus genome contains a strikingly high representation (11) of genes related to merR, whose products typically exert their regulatory effects by compensating for aberrant spacing between the −10 and −35 regions of the promoters they regulate (95). There are two putative hspR genes for the regulation of the heat shock response (Mlut_00590 and Mlut_18780), both located next to dnaJ-like genes, and three genes for ArsR-like regulators. The arsR-like genes are adjacent to genes encoding a cation (zinc, cobalt, and cadmium) diffusion facilitator (Mlut_13910), an arsenic resistance protein (Mlut_20620), and a cadmium transporter (Mlut_20660), and they are all located in regions mainly comprising M. luteus-specific genes (see above). One of the merR-like genes (Mlut_06140) is close to genes involved in mercury resistance (e.g., mercuric reductase, Mlut_06150), and another (Mlut_20770) is related to certain excisionases. At least four of the MerR/ArsR proteins are likely to play a role in metal resistance, which is of interest since M. luteus may have potential utility for gold recovery from low-grade ores (66, 67).

Cell division, morphogenesis, and peptidoglycan biosynthesis.

Many of the known genes dedicated to peptidoglycan synthesis, cell division, and morphogenesis are conserved between M. luteus and M. tuberculosis. M. luteus peptidoglycan is of subgroup A2, in which an l-Ala-d-Glu-l-Lys-d-Ala stem peptide (with a glycyl modification of the d-Glu component) is cross-linked to the d-Ala residue of its counterpart by an identical tetrapeptide (107). All but one of the expected genes required for production of a UDP-N-acetylmuramate-pentapeptide-N-acetylglucosamine precursor were readily identified (Table 4), the exception being that for the enzyme responsible for the glycinyl modification of the d-glutamate residue of the stem peptide.

TABLE 4.

M. luteus genes concerned with production of polyprenyl lipid-linked peptidoglycan monomer precursors

| Gene | Mlut identifier | Product function |

|---|---|---|

| murA | Mlut_08760 | UDP-GlcNAc carboxyvinyltransferase |

| murB | Mlut_17500 | UDP-MurNAc dehydrogenase |

| murC | Mlut_13590 | UDP-MurNAc-l-Ala ligase |

| murD | Mlut_13620 | UDP-MurNAc-l-Ala-d-glutamate ligase |

| murE | Mlut_13650 | UDP-MurNAc-l-Ala-d-Glu-l-Lys ligase |

| alr | Mlut_13550 | Alanine racemase |

| ddl | Mlut_08790 | d-Ala-d-Ala ligase |

| murF | Mlut_13640 | UDP-MurNAc-tripeptide d-Ala-d-Ala ligase |

| mraY | Mlut_13630 | Phospho-MurNac-pentapeptide transferase |

| murG | Mlut_13600 | Polyprenyl diphospho-MurNAc-pentapeptide GlcNAc transferase |

| murI | ? | UDP-MurNAc penatapeptide (d-Glu) glycinyltransferase |

Schleifer and Kandler (106, 107) proposed that the use of a stem peptide as a functional interpeptide, which is a feature of M. luteus peptidoglycan, could involve cleavage between the N-acetylmuramate moiety of one PG monomer and the l-Ala of its peptide component after that peptide had been directly cross-linked to the l-Lys of a neighboring chain. Thereafter, the terminal d-Ala would be linked to the ɛ-amino group of the l-Lys of a third stem peptide. Either a single transpeptidase (TP) with broad acceptor specificity, or two specific TPs are required. The Mlut_16840 product, which is probably a member of the amidase_2 superfamily (pfam 01510, 9e−15 BIT score of 53.7), appears to be a strong candidate for the N-acetylmuramoyl-l-alanine amidase. It bears a twin-arginine transporter type N-terminal signal sequence in conjunction with a Cys residue occupying position 33, suggesting that it is a lipoprotein, as required for this proposed function.

According to Ghuysen (35), class A high-molecular-mass-penicillin-binding proteins (HMM-PBPs) can perform all of the basic functions required for PG polymerization. Many bacteria possess several class A HMM-PBPs (37) that may functionally substitute for each other (57), but M. luteus possesses only one, encoded by Mlut_18460.

Class B HMM-PBPs possess transpeptidase activity and contain additional modules that may mediate protein-protein interactions (44) or assist with protein folding (37). They are involved in septation, lateral wall expansion and shape maintenance (48, 100, 120, 136). M. luteus and M. tuberculosis share similar complements of class B HMM-PBPs. As is seen with the cognate M. tuberculosis genes, Mlut_13660 (ftsI) is associated with the division/cell wall (DCW) cluster and Mlut_00770 is clustered with other genes encoding cell division and cell shape-determining factors such as FtsW and the regulatory elements PknAB (37). M. luteus lacks an ortholog of the third M. tuberculosis PBP, Rv2864c, which may contribute to its well-known β-lactam sensitivity.

The products of Mlut_01190 and Mlut_16800, potentially d-alanyl-d-alanine carboxypeptidases, may be involved in cell wall remodeling or provide the extra TP potentially required to incorporate the interpeptide unit of PG. Mlut_16800 is close to Mlut_16840, encoding the putative MurNAc-l-alanine amidase that may also be involved in this process. Similarly, the putative soluble murein transglycosylase encoded by Mlut_13740 probably participates in cell wall remodeling.

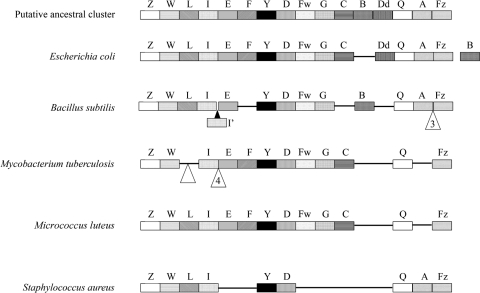

The DCW cluster is present in many organisms, and a hypothetical archetypal cluster has been defined (92, 114) (Fig. 5) that has been broadly maintained in bacilli. It has been dispersed or rearranged in other lineages such as coccal firmicutes or has been modified to accommodate developmental processes such as sporulation (75). Most of the genes that have dispersed from the DCW clusters of Gram-positive organisms encode enzymes that supply cytoplasmic PG precursors. The organization of the M. luteus DCW cluster appears almost identical to that of its rod-shaped relative, M. tuberculosis. This might seem paradoxical given the dispersal that has occurred in other lineages (e.g., firmicutes), in which representatives have developed a coccoid morphology. However, unlike B. subtilis and E. coli, actinomycetes (including the rod-shaped M. tuberculosis) do not show appreciable intercalary insertion of new PG; this activity is more or less restricted to the cell poles (126). It is not known whether the spherical shape of M. luteus cells masks a hidden polarity in relation to growth and division.

FIG. 5.

Conservation of division/cell wall (DCW) clusters. The DCW clusters of several bacteria are schematically represented. Coding sequences are not drawn to scale, in order to facilitate alignment. The triangles denote the positions of single gene insertions unless numerals are present that indicate the insertion of multiple genes. Where orthologues are absent from the cluster but retained at a locus nearby, they are placed to one side. The key to the gene symbols placed above each cluster are as follows: Z, mraZ; W, mraW; L, ftsL; I, ftsI; I′, spoVD; E, murE; Y, mraY; D, murD; Fw, ftsW; G, murG; C, murC; B, murB, Dd, ddlB; Q, ftsQ; A, ftsA; Fz, ftsZ.

The Div1B/FtsQ proteins encoded by the DCW clusters found in several cocci possess an extended hydrophilic region immediately preceding the largest hydrophobic region of the protein toward the N terminus (98). Although FtsQ from several actinobacteria (M. tuberculosis C. glutamicum, Arthrobacter spp., K. rhizophila, and R. salmoninarum) also possesses this extended hydrophilic region, it is absent from the M. luteus FtsQ homolog encoded by Mlut_13580, which is some 90 residues shorter. Moreover, the N terminus of the predicted M. luteus protein lacks 33 amino acid residues compared to B. subtilis Div1B, inviting the speculation that these differences in protein architecture may have functional significance in the organism's transition to a coccoid form.

Two of the STPK determinants (see above), the pknAB genes, are part of a conserved actinobacterial gene cluster implicated in cell division and morphogenesis that also includes rodA (Mlut_00780), whose product is involved in the control of cell shape, pbpA (Mlut_00770) encoding a transpeptidase involved in PG cross-linking, and pstP (Mlut_00790) encoding a protein phosphatase that dephosphorylates PknA and PknB in M. tuberculosis (13, 21). In M. tuberculosis, the genes in this cluster have a single transcriptional start site and the start and stop codons of successive genes overlap, suggesting transcriptional and translational coupling. This relationship is apparently conserved in M. luteus. Furthermore, the extracellular domain of PknB has been described as a penicillin-binding and Ser/Thr kinase-associated (PASTA) domain that is also found in the bifunctional HMM-PBPs involved in PG synthesis. This domain may bind both penicillins and PG-related analogues (141), as well as muropeptides, effectively coupling cell envelope synthesis to other core processes including transcription and translation (111). One of the phosphorylation targets of M. tuberculosis PknA is the product of wag31 (50). This essential gene (104), also found in M. luteus (Mlut_13520) with a conserved genetic context and neighboring the DCW cluster, encodes a homolog of DivIVA that controls placement of the division septum in B. subtilis (18) but appears to differ functionally in actinomycetes. Recent studies using C. glutamicum and other actinobacteria suggest its role in polar peptidoglycan synthesis is more significant than its involvement in septation (65, 105).

Anionic wall polysaccharides.

The cytoplasmic membrane of M. luteus bears a α-d-mannosyl-(1→3)-α-d-mannosyl-(1→3)-diacylglycerol (Man2-DAG) glycolipid and a succinylated lipomannan (sucLM) based on it (64, 94, 97). The lipomannan components of Corynebacterium glutamicum and M. luteus have structural similarities (76, 77, 124), and the genes encoding sucLM biosynthesis in M. luteus were identified by comparison with the cognate genes from C. glutamicum. The product of Mlut_04450 is a strong candidate for one of the mannosyltransferases that forms Man2-DAG. Genes encoding homologs of MptA (Mlut_09700) and MptB (Mlut_09690) form a cluster with another gene (Mlut_09710) that encodes a GT-C family glycosyltransferase, suggesting that Mlut_09710 is also involved in sucLM biosynthesis. These three genes are cotranscribed and probably translationally coupled, since each overlaps its predecessor by four nucleotides, suggesting coordinate regulation through a polycistronic mRNA, whereas their homologs in corynebacteria and mycobacteria are widely dispersed. Assuming Mlut_09690 and Mlut_09700 are MptBA orthologues, they would, in concert, provide an α-(1→6) linked mannosyl backbone, a common feature in other lipoglycans. Mlut_09710 might then provide either the 2- or 3-linked mannose residues reported in early characterizations (108). However, it is also possible that each of these three GT-C glycosyltransferases produces a distinct linkage and that this operon provides all of the biosynthetic capability to produce the bulk of the sucLM mannan. A homolog of mycobacterial and corynebacterial polyprenyl monophosphomannose synthases, necessary to provide mannosyl donors to MptAB, is encoded by Mlut_12000. Interestingly, a gene encoding a C-N hydrolase commonly found immediately downstream or, in the case of M. tuberculosis, fused in a continuous reading frame, is absent from M. luteus (36, 41).

The M. luteus cell wall is decorated with a teichuronic acid (TUA) consisting of repeating disaccharide units of N-acetyl-mannosaminuronic acid (ManNAcU) and glucose (Glc) (42, 47). The polymer is attached to PG via the phosphate group of a reducing terminal trisaccharide consisting of two ManNAcU residues and an N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) phosphate residue (33). The TUA operon of B. subtilis provides few useful search queries, and the genes concerned with TUA biosynthesis in most other organisms have not been well characterized. M. luteus contains three homologs of UDP-ManNAcU dehydrogenase (Mlut_05630, Mlut_08960, and Mlut_08980), which might produce the ManNAcU nucleotide donor. Mlut_05630 is clustered with a single putative glycosyltransferase (Mlut_05650) and two other genes of unknown function, while Mlut_08960 and Mlut_08980 lie within a large cluster encoding several putative GTs, as well as other functions necessary for TUA biosynthesis and export. The individual glycosyl residues of the repeating polymer unit are both derived from UDP-glycosyl donors (43). A likely biosynthetic route to UDP-ManNAcU, predominantly based in this cluster, is apparent. UDP-GlcNAc may be formed by the Mlut_05450 product, a homolog of E. coli GlmU (a bifunctional enzyme with glucosamine-1-phosphate N-acetyltransferase and GlcNAc-1-phosphate uridyltransferase activities). UDP-GlcNAc could then be transformed to UDP-ManNAc via a putative UDP-GlcNAc 2-epimerase encoded by Mlut_09080. The oxidation of this precursor to UDP-ManNAcU could be achieved by either of the UDP-N-acetyl-d-mannosaminuronate dehydrogenase homologs encoded by Mlut_08960 or Mlut_08980. Mlut_08720 appears to encode a UDP-Glc 6-dehydrogenase; together with the apparent aminosugar preference of both Mlut_08960 and Mlut_08980, this suggests that there may be greater heterogeneity in TUA biosynthesis than is currently recognized. Since both Mlut_08960 and Mlut_08980 appear to be twinned with GT genes as immediate upstream neighbors, these might reflect potentially interchangeable functional units for the introduction of aminosugar-derived glycuronic acid residues into a TUA polymer.

The complement of GTs necessary for TUA biosynthesis can be estimated from biochemical data. A polyprenyl pyrophosphate-GlcNAc-(ManNAc)2 acceptor is synthesized initially and then extended by separable Glc and ManNAcU transferases that intervene alternately in polymer elongation (43, 122). Acceptor synthesis will require TagO (Mlut_08100), a polyprenyl phosphate-dependent GlcNAc phosphate transferase that is implicated universally in the attachment of polymers to PG together with (probably) two ManNAcU transferases. The only partially characterized GT involved in M. luteus TUA biosynthesis is the glucosyltransferase responsible for the deposition of the α-d-Glc residues within the polymer; two apparent subunit types of mass 54 kDa and 52.5 kDa with an estimated pI of ∼5 for the octameric active enzyme were described previously (25). These parameters show a good match with the predicted GT product of Mlut_09020 (molecular mass = 56.8 kDa, pI = 5.94). Finally, the secretion of the TUA may be accomplished by the products of Mlut_09060 and Mlut_09070, which together constitute a predicted ABC family polysaccharide export system.

The Mlut_08990, Mlut_09000, and Mlut_09010 genes that complete this cluster encode products related to aminosugar-N-acetyltransferases, a pyridoxal phosphate-dependent aminotransferase and a dehydrogenase, respectively. These activities are consistent with the provision of a further N-acetylated amino sugar for glycuronic acid formation. Interestingly, Mlut_09000 is a pseudogene; analysis of the in silico-translated sequence reveals homology with several predicted UDP-4-amino-4-deoxy-l-arabinose-oxoglutarate aminotransferases over the full sequence length with the incorporation of a stop codon through a nucleotide substitution in codon 121. Thus, the structure of this gene cluster is entirely consistent with the biosynthesis of the TUA described for M. luteus and taken together with the apparent redundancy in N-acetylglycosaminuronate provision and transfer, the apparent loss of Mlut_09000 function suggests a previously more diverse TUA profile.

Energy metabolism.

The M. luteus genome contains genes encoding the various respiratory chain components, including complex I (NADH-quinone oxidoreductase: Mlut_18970 to Mlut_18940, Mlut_11050, Mlut_11060, and Mlut_05010), complex II (succinate dehydrogenase with cytochrome b and a Fe-S cluster: Mlut_04850 to Mlut_04820), and complexes III and IV (quinol-cytochrome c oxidoreductase with cytochrome b and a Fe-S center and the cytochrome c-cytochrome aa3 oxidase complex: Mlut_12150 to Mlut_12120, Mlut_12210, and Mlut_12220). The M. luteus respiratory chain also contains the quinol-oxidase complex with cytochrome bd (Mlut_13220 and Mlut_13210), which is usually responsible for the growth of bacteria under low-oxygen conditions (128). Genes encoding a membrane-bound malate-menaquinone oxidoreductase (Mlut_08440) and transmembrane l-lactate-menaquinone oxidoreductase (Mlut_21510) are present, and the corresponding activities have been demonstrated experimentally in isolated membrane particles (5). The M. luteus respiratory chain may also contain a membrane-bound pyruvate dehydrogenase (cytochrome; Mlut_02710), glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Mlut_23030), and l-proline dehydrogenase (Mlut_19430) as in C. glutamicum (14).

Central carbon metabolism.

Genes encoding a complete set of enzymes of the citric acid cycle are present. The genes for the α and β subunits of succinyl coenzyme A (CoA) synthetase lie adjacent to each other (Mlut_04280 and Mlut_04270) and genes for the succinate dehydrogenase subunits A to D form a cluster (Mlut_04820 to Mlut_04850). The other genes encoding citrate synthase (Mlut_15490), aconitase (Mlut_13040), isocitrate dehydrogenase (Mlut_04530), the E1 and E2 components of 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase (Mlut_07730 and Mlut_13330), fumarase (Mlut_05170), and malate dehydrogenase (Mlut_00950) are located separately.

M. luteus can use acetate as a sole source of carbon for energy and growth (V. Artsatbanov, unpublished results), so it must contain the isocitrate lyase and malate synthase A components of the glyoxylate shunt (and, despite its small genome, must have all of the necessary pathways to synthesize amino acids, nucleotides, carbohydrates, and lipids from acetate). The isocitrate lyase and malate synthase A components are functionally active (E. Salina, unpublished results), and they are encoded by adjacent genes (Mlut_02080 and Mlut_02090). Interestingly, the isocitrate lyase is considered a “persistence factor” in M. tuberculosis, where it “allows net carbon gain by diverting acetyl-CoA from β-oxidation of fatty acids into the glyoxylate shunt pathway” (74, 112).

All of the main enzymes of glycolysis are present other than the first enzyme, glucokinase, responsible for the phosphorylation of glucose. This is consistent with the observed inability of M. luteus to grow with glucose as sole carbon source (140), but it may not serve to explain it, since the product of Mlut_13470 is predicted to be a polyphosphate glucokinase. Other closely related species, e.g., R. salmoninarum, Arthrobacter spp., and Rhodococcus sp., do have glucokinase genes. M. luteus is able to synthesize all glycolytic intermediates (presumably by gluconeogenesis) from phosphoenolpyruvate or pyruvate obtained from oxaloacetate through the agency of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (Mlut_03380) or pyruvate carboxylase (Mlut_13810). It has a complete complement of enzymes concerned with triose metabolism, and genes for all of the pentose phosphate pathway enzymes are annotated except for 6-phosphogluconolactonase. Although this open cycle could produce all intermediates, pentoses would presumably be synthesized via the nonoxidative pentose phosphate pathway that is not coupled to the reduction of NADP+.

Does glycogen serve mainly as a biosynthetic intermediate for trehalose in M. luteus?

One remarkable feature of some actinobacteria is the importance of the glucose-related storage metabolites, trehalose and glycogen, and the complexity of associated metabolic processes: in some organisms, this area of metabolism appears to be essential for viability (9, 17). There are at least three ways in which mycobacteria and streptomycetes can make trehalose (17) and some interconnections between trehalose and glycogen metabolism (110).

M. luteus has strikingly fewer genes concerned with carbohydrate metabolism than its close relatives (Table 2). All of the genes for conventional glycogen biosynthesis from central metabolism are present: pgm (Mlut_01060), glgA (Mlut_11690), glgB (Mlut_03850), glgC (Mlut_11680), together with a debranching enzyme gene, glgX (Mlut_16760), and the incompletely characterized, glycogen-related gene glgE (Mlut_03840). Remarkably, however, there is no obvious candidate gene for glycogen phosphorylase, a highly conserved enzyme that is almost universal and which provides the major route for glycogen breakdown. This raises the question of whether M. luteus can metabolize glycogen.

Equally surprising is the absence of the otsAB genes for the conventional synthesis of trehalose. However, in the last 10 years, another pathway (present in many actinobacteria) has been discovered, in which the terminal reducing glucosyl residue on chains of α-1,4-linked glucose polymers is “flipped” by the TreY trehalose malto-oligosyl trehalose synthase enzyme so that it is now α-1,1-linked, and then this terminal trehalosyl disaccharide is cleaved off by the TreZ malto-oligosyltrehalose trehalohydrolase enzyme. This pathway is present in M. luteus (Mlut_03980, treY; Mlut_03990, treZ) and could therefore provide a route for glycogen breakdown to give trehalose. In other Micrococcaceae, greater numbers of trehalose biosynthetic genes have been annotated (four in Arthrobacter sp. strain FB24, six in K. rhizophila, and eight in R. salmoninarum and A. aurescens TC1), and in more distantly related organisms such as C. glutamicum, multiple trehalose biosynthetic pathways may be present (139). The degradation of trehalose to yield glucose is catalyzed by trehalase. Although it is generally difficult to recognize trehalases by homology, Mlut_17860 encodes a protein with 35% identity to a trehalase recently characterized in M. smegmatis (17). It seems possible that the breakdown of glycogen in M. luteus may well take place via trehalose.

Another pathway for trehalose biosynthesis, found in many actinobacteria, uses the trehalose synthase enzyme to interconvert maltose and trehalose (see reference (110 and references therein). There is no close homolog of treS in M. luteus. Thus, the only obvious route for trehalose synthesis appears to be via glycogen. In this respect, it is relevant to note that the treYZ genes of M. luteus are separated from glgE and glgB only by a group of genes peculiar to M. luteus that were therefore probably acquired by lateral gene transfer. The glg and tre genes may previously have been adjacent, which is consistent with the idea of a combined glycogen-trehalose biosynthetic pathway. We are not aware of a comparable system in any other organism.

M. luteus has relatively little capacity for secondary metabolism.

The genome of M. luteus includes only 39 genes (2.2%) annotated as being concerned with secondary metabolism (Table 2). Among these are 11 clustered genes (Mlut_21170-21270) implicated in carotenoid synthesis (Table 5). Yellow pigmentation has long been important for the identification of M. luteus, suggesting that the genes concerned with pigment production would show a restricted distribution. The phytoene synthetase (Mlut_21230), phytoene desaturase (Mlut_21220), and polyprenyl transferase (Mlut_21210) genes lie in the center of the cluster and have homologs in many different organisms, including the photosynthetic bacteria (Synechococcus), where the carotenoids might function to protect against radiation damage, as has been proposed in M. luteus (4). Other genes toward the extremities of the cluster show a more restricted distribution (Table 6). Although homologs of most of these genes are present in other high G+C Gram-positive bacteria, a high level of synteny is restricted to only a few organisms, e.g., L. xyli, Corynebacterium efficiens, C. glutamicum, and C. michiganensis.

TABLE 5.

Genes involved in carotenoid production

| Mlut | Amino acid | Annotation | Commenta | EC or COG no. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 21270 | 143 | Thioredoxin | Ubiquitous oxidoreductase | 1.8.7.1. |

| 21260 | 209 | Isopentenyl diphosphate delta isomerase | 3-Isopentenyl pyrophosphate → dimethylallyl pyrophosphate | 2.5.1.1 (?) |

| 21250 | 182 | Hypothetical | No matches | |

| 21240 | Geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate synthase | trans, trans-Farnesyl diphosphate + isopentenyl diphosphate → diphosphate + geranylgeranyl diphosphate | 2.5.1.29 | |

| 21230 | 298 | Squalene/phytoene synthetase | Probably phytoene synthetase 2 geranylgeranyl diphosphate → diphosphate + prephytoene diphosphate | 2.5.1.32 |

| 21220 | 566 | Phytoene desaturase | Carotene desaturation, a step in carotenoid biosynthesis | COG1233 |

| 21210 | 294 | 4-Hydroxybenzoate polyprenyltransferase and related prenyltransferases | crtEB lycopene elongation | 2.5.1.39 |

| 21200 | 129 | Putative C50 carotenoid epsilon cyclase | crtYe ring closure | |

| 21190 | 117 | Hypothetical | Matches short segments of lycopene e-cyclase isoprenoid and putative C50 carotenoid epsilon cyclase (crtYf) |

Notations for the genes crtEB, crtYe, and crtYf are as cited for Corynebacterium glutamicum (63).

TABLE 6.

Distribution of genes involved in carotenoid synthesis

| Organism | Distribution of genea: |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mlut_21190 (partial carotenoid cyclase) | Mlut_21200 (C50 carotenoid epsilon cyclase) | Mlut_21210 (polyprenyl transferase) | Mlut_21220 (phytoene desaturase) | Mlut_21230 (phytoene synthetase) | Mlut_21240 (geranylgeranyl synthase) | Mlut_21250 (hypothetical) | Mlut_21260 (isopentenyl isomerase) | |

| Actinobacteria | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| Alphaproteobacteria | + | + | + | |||||

| Betaproteobacteria | + | |||||||

| Gammaproteobacteria | + | |||||||

| Deltaproteobacteria | + | + | + | + | ||||

| Firmicutes | + | + | ||||||

| Archaea | + | + | + | + | + | |||

| Green nonsulfur | + | + | ||||||

| Green sulfur | + | + | ||||||

| Cyanobacteria | + | + | ||||||

| Planctomycetes | + | + | + | |||||

| Verrucomicrobiae | + | |||||||

| Basidiomycetes | + | |||||||

| Ascomycetes | + | |||||||

The gene type or description is given in parentheses.

There is little evidence from the genome annotation for the presence of other secondary metabolic functions. There is a cluster of genes involved in siderophore transport (Mlut_22080 to Mlut_22120), as well as single genes that, according to the annotation, might be involved in nonribosomal peptide synthesis (COG1020) and benzoate catabolism (protocatechuate 3,4-dioxygenase [COG3485]). The genome is among the minority of actinobacterial genomes (including C. diphtheriae and Tropheryma whipplei) that encode no obvious cytochromes P450; for example, free-living mycobacteria and streptomycetes generally encode more than 10 (130). There is no evidence for a significant repertoire of genes that might be involved in polyketide production (only Mlut_20260 and Mlut_22550) or xenobiotic catabolism. Finally, M. luteus uses the nonmevalonate pathway for C5 isoprenoid biosynthesis (Table 7). The genes are dispersed about the bacterial chromosome with Mlut_03780 encoding a bifunctional enzyme comprising IspD (2-C-methyl-d-erythritol 4-phosphate cytidylyltransferase [EC 2.7.7.60]) and IspF (2-C-methyl-d-erythritol 2,4-cyclodiphosphate synthase [EC 4.6.1.12]), as is also the case in several other actinobacteria, e.g., Kytococcus sedentarius, C. michiganensis, L. xyli, and T. whipplei (58, 48, 46, and 42% identities, respectively).

TABLE 7.

Comparison of the nonmevalonate pathway for isoprenoid biosynthesis in M. luteus and My. tuberculosis

| Enzyme (EC no.) | M. tuberculosis gene | M. luteus homologa | % Identity |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1-Deoxy-d-xylulose-5-phosphate synthase (2.2.1.7) | Rv2682c, dxs1 | Mlut_13030 | 57.5 |

| 1-Deoxy-d-xylulose 5-phosphate reductoisomerase (1.1.1.267) | Rv2870c, dxr | Mlut_06920 | 56.3 |

| 2-C-methyl-d-erythritol 4-phosphate cytidylyltransferase (2.7.7.60) | Rv3582c, ispD | Mlut_03780* | 42.6 |

| 4-Diphosphocytidyl-2-C-methyl-d-erythritol kinase (2.7.1.148) | Rv1011, ispE | Mlut_05400 | 44.7 |

| 2-C-methyl-d-erythritol 2,4-cyclodiphosphate synthase (4.6.1.12) | Rv3581c, ispF | Mlut_03780* | 60.5 |

| 4-Hydroxy-3-methylbut-2-en-1-yl diphosphate synthase (1.17.4.3) | Rv2868c, ispG (gcpE) | Mlut_06940 | 77.23 |

| 4-Hydroxy-3-methylbut-2-enyl diphosphate reductase (1.17.1.2) | Rv1110, ispH, lytB | Mlut_16300 | 62.7 |

| Isopentenyl-diphosphate delta-isomerase (5.3.3.2) | Rv1745c, idi | Mlut_21260 | 46.4 |

*, Mlut_03780 encodes a bifunctional enzyme, as also occurs in some other actinobacteria (see the text).

Osmotolerance.

M. luteus is salt tolerant and grows in rich medium, such as nutrient broth, containing 10% NaCl, although pigment production is abolished at concentrations greater than 5% NaCl (G. Price and M. Young, unpublished data). Heterotrophic bacteria that are salt requiring or salt tolerant generally use organic solutes such as amino acids (glutamate, proline), glycine betaine, ectoine, and trehalose for osmotic balance.

When grown in rich medium, most heterotrophic bacteria accumulate glycine betaine (46). However, very few heterotrophs are capable of de novo synthesis of betaine; they tend to accumulate the compound from the medium (yeast extract is a good source of betaine). Accordingly, M. luteus encodes an ABC transporter system for proline/glycine betaine with four components clustered in the genome (Mlut_15720 to Mlut_15750). In addition, two choline/carnitine/betaine transporters have also been annotated (Mlut_01900 and Mlut_16530). All of these genes have homologs throughout the actinobacteria.

Although an ectoine synthetase gene is annotated (Mlut_02920), the remainder of the operon required for production of this molecule is apparently absent. The M. luteus gene has greatest similarity to genes found in Stigmatella aurantiaca and Burkholderia ambifaria (55 and 54% identities, respectively), in which the remaining genes required for ectoine synthesis are also apparently absent. Complete ectoine operons are found in the genomes of many actinobacteria including Brevibacterium linens BL2 and Streptomyces avermitilis.

As noted above, M. luteus has two genes potentially concerned with trehalose production from glycogen: a trehalose malto-oligosyl trehalose synthase (Mlut_03980) and a malto-oligosyltrehalose trehalohydrolase (Mlut_03990). This suggests that of the common compatible solutes, M. luteus can only produce glutamate, proline, and trehalose (the last of these only via glycogen) although, like many heterotrophic bacteria, it does have transporters for other compatible osmoprotectants.

Long-chain alkene biosynthesis by M. luteus.

Four decades ago, two research groups studying a close relative of M. luteus, Sarcina lutea ATCC 533 (now Kocuria rhizophila), reported the biosynthesis of iso- and anteiso-branched, long-chain (primarily C25 to C29) alkenes (1, 2, 127). Although the biosynthetic pathway was postulated to involve decarboxylation and condensation of fatty acids, the underlying biochemistry and genetics of alkene biosynthesis have remained unknown until very recently. M. luteus strains have also been shown to produce primarily branched C29 monoalkenes; this includes the sequenced strain (based upon analysis by gas chromatography-chemical ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry [9a]) and strain ATCC 27141 (31).

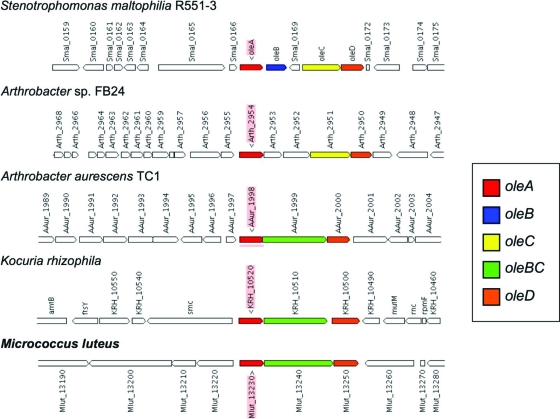

Recently, Friedman and Rude (international patent application WO 2008/113041) reported that heterologous expression of oleACD from a range of bacteria (including Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, Xanthomonas axonopodis, and Chloroflexus aggregans) resulted in long-chain alkene biosynthesis, and in vitro studies indicated that the alkenes indeed result from fatty acyl-CoA or fatty acyl-ACP precursors. Beller and coworkers have heterologously expressed the three-gene M. luteus cluster comprising oleA (Mlut_13230), oleBC (a gene fusion; Mlut_13240), and oleD (Mlut_13250) in E. coli and observed C27 and C29 alkenes that were not detectable in negative controls with a plasmid lacking any M. luteus genes (9a). In vitro studies with M. luteus OleA indicated that it catalyzes decarboxylation and condensation of activated fatty acids (9a).

Some close relatives of M. luteus that also produce long-chain alkenes, such as K. rhizophila and A. aurescens TC1, have similar oleABCD gene organization (Fig. 6) and a relatively high degree of sequence identity. To illustrate, the OleA, OleBC, and OleD sequences of K. rhizophila and A. aurescens TC1 share 45 to 57% identity with those of M. luteus. In contrast, Arthrobacter sp. strain FB24, which does not produce alkenes (31), appears to lack an oleB gene and has OleA and OleD sequences that share only 25 to 27% sequence identity with those of M. luteus. It is possible that the divergence of ole sequences in strain FB24 from those in the other strains discussed here explains its inability to produce long-chain alkenes. In the Gram-negative, alkene-producing bacterium S. maltophilia, oleB and oleC are separate genes, in contrast to the Gram-positive species represented in Fig. 6, but there is still relatively strong similarity between the S. maltophilia and M. luteus sequences (e.g., OleA and OleD both share 39% sequence identity between these two organisms).

FIG. 6.

Organization of the ole (olefin synthesis) genes in M. luteus and other bacteria.

Although BLASTp searches with M. luteus OleA (Mlut_13230) showed best hits to β-ketoacyl-ACP-synthase III (FabH), a key enzyme involved in fatty acid biosynthesis, the true fabH in the M. luteus genome, Mlut_09310, falls in a cluster of genes critical to the biosynthesis of branched-chain fatty acids, including a putative branched-chain α-keto acid decarboxylase (Mlut_09340), malonyl-CoA:ACP transacylase (fabD; Mlut_09320), acyl carrier protein (ACP; Mlut_09300), and β-ketoacyl-ACP-synthase II (fabF; Mlut_09290).

Dormancy.

M. luteus can enter a profoundly dormant state from which it can be resuscitated by a secreted protein called resuscitation-promoting factor (Rpf) (85). Among its closest relatives, Arthrobacter sp. strain FB24, R. salmoninarum, and K. rhizophila, all encode a secreted protein with an N-terminal transglycosylase-like domain and a C-terminal LysM domain that closely resembles M. luteus Rpf (123, 137). A second protein belonging to the highly conserved RpfB family (99) is encoded by genes found in Arthrobacter sp. strain FB24 and R. salmoninarum. RpfB is also present in Arthrobacter aurescens TC1, which does not encode a protein with a domain structure similar to that of M. luteus Rpf.

Dormancy has been extensively studied in M. tuberculosis, which has five rpf genes involved in controlling culturability and resuscitation (12, 27, 86, 102, 113, 129), and the remainder of this section will focus on a comparison with this organism. In M. tuberculosis, a state of growth arrest often referred to as dormancy is occasioned by hypoxia in vitro (135). This leads to the expression of a cohort of ca. 50 genes (the Dos regulon) under the control of the devRS (dosRS) two-component system (101). Microarray studies have been accomplished using five different dormancy models and many genes belonging to the Dos regulon are upregulated in these datasets (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). Throughout these datasets, between 45 and 50% of the genes that are significantly upregulated have homologs in M. luteus (Table 8). Several of the M. luteus genes in these lists have multiple paralogs in M. tuberculosis, the most striking example being Mlut_01830. This gene encodes the universal stress protein UspA. It is represented once in the M. luteus genome, whereas there are six homologs in M. tuberculosis (Rv1996, Rv2005c, Rv2028c, Rv2623, Rv2624c, and Rv3134c). Out of a cohort of 17 genes that are upregulated in all five M. tuberculosis dormancy models in Table S2 in the supplemental material, nine have homologs in M. luteus (Table 9). Notable among these are genes encoding the universal stress protein UspA (Mlut_01830), ferredoxin (Mlut_15510), an erythromycin esterase homolog (Mlut_05460), an Hsp20 family heat shock protein (Mlut_16210) and a zinc metalloprotease (Mlut_11840) that lies within a cluster including putative proteasome components. This cluster shows a high degree of synteny with Arthrobacter sp. strain FB24.

TABLE 8.

Number of genes upregulated (>3-fold induction) in different models of M. tuberculosis dormancy and their M. luteus homologsa

| Parameter | All genes | Genes seen in: |

Nonreplicating persistence |

Chemostat model | Seen in both NRP1 and NRP2 | Macrophages activated for 48 h | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| >2 models | All 5 models | NRP1, 8 days | NRP2, 20 days | |||||

| Reference | 132 | 132 | 7 | 92 | 109 | |||

| Total no. | 247 | 72 | 17 | 55 | 94 | 52 | 90 | 111 |

| No. of homologs in M. luteus | 137 | 36 | 9 | 24 | 53 | 30 | 44 | 61 |

| % with M. luteus homolog | 55.5 | 50.0 | 53 | 43.6 | 56.4 | 57.7 | 48.9 | 55.0 |

Minimum 20% identity; maximum e value 1e−2. A low stringency was used to identify as many genes as possible in M. luteus that might be homologs of the dormancy-related genes of M. tuberculosis. Even so, comparatively few candidates emerged from the analysis. Despite a significant reduction in the number of “dormancy-related” genes, M. luteus can readily adopt a dormant state.

TABLE 9.

Many of the genes upregulated in all 5 My. tuberculosis dormancy models have M. luteus homologs

| M. tuberculosis locus taga | Product name and/or assignment | M. luteus homolog | Product name and/or assignment | E-value | % Identity/BIT score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rv0079 | Hypothetical protein | ||||

| Rv0080 | Conserved hypothetical protein | Mlut_04380 | Predicted flavin-nucleotide-binding protein | 3e-08 | 30.4/50 |

| Rv1733c | Possible membrane protein | ||||

| Rv1738 | Conserved hypothetical protein | ||||

| Rv1996 | COG0589: universal stress protein UspA and related nucleotide-binding proteins | Mlut_01830 | Universal stress protein UspA and related nucleotide-binding proteins | 9e-29 | 31.6/120 |

| Rv2007c | Ferredoxin | Mlut_15510 | Ferredoxin | 5e-36 | 58.0/142 |

| Rv2030c | COG2312: erythromycin esterase homolog COG1926: predicted phosphoribosyltransferases | Mlut_18600b | Amidophosphoribosyltransferase (EC 2.4.2.14) | 1e-03 | 27.9/38 |

| Rv2031c | 14-kDa antigen, heat shock protein Hsp20 family | Mlut_16210 | Heat shock protein Hsp20 (IMGterm) | 6e-09 | 36.9/52 |

| Rv2032 | Conserved hypothetical protein Acg | ||||

| Rv2623 | COG0589: universal stress protein UspA and related nucleotide-binding proteins | Mlut_01830c | Universal stress protein UspA and related nucleotide-binding proteins | 4e-34 | 36.8/137 |

| Rv2624c | COG0589: universal stress protein UspA and related nucleotide-binding proteins | Mlut_01830 | Universal stress protein UspA and related nucleotide-binding proteins | 7e-22 | 32.4/97 |

| Rv2625c | COG1994: Zn-dependent proteases (probable conserved transmembrane alanine and leucine-rich protein) | Mlut_11840 | Zn-dependent proteases | 7e-31 | 30.1/127 |

| Rv2626c | Conserved hypothetical protein | ||||

| Rv2627c | Conserved hypothetical protein | ||||

| Rv3127 | Conserved hypothetical protein | ||||

| Rv3130c | IGR02946 acyltransferase, WS/DGAT/MGAT | ||||

| Rv3134c | COG0589: universal stress protein UspA and related nucleotide-binding proteins | Mlut_01830 | Universal stress protein UspA and related nucleotide-binding proteins | 2e-16 | 36.4/78 |

All genes except Rv1733c belong to the DOS regulon.

Three more homologs.

One more homolog.

Recent studies of the enduring hypoxic response of M. tuberculosis (103) revealed that more than 200 genes are upregulated, only five of which belong to the Dos regulon, and only two of these five were upregulated by more than threefold (103). However, comparison of the 47 genes upregulated more than threefold in the enduring hypoxic response with upregulated genes from the other five dormancy models (Table 8) showed that 22 of them (47%) were upregulated by more than threefold in at least one of those models. 62% of these 47 genes have homologs in the M. luteus genome (Table S3 in the supplemental material).

M. luteus therefore contains many genes similar to genes upregulated in different M. tuberculosis dormancy models. Among them are members of the Dos regulon, including the devRS (dosRS) genes encoding the sensory histidine kinase and response regulator that control the regulon (possibly Mlut_18530 and Mlut_18540, although other gene pairs, such as Mlut_16250 and Mlut_16240 or Mlut_21850 and Mlut_21860, might fulfill this role). The total number of M. luteus dormancy-related genes revealed by these various comparisons is roughly proportional to the twofold difference in genome size between M. luteus and M. tuberculosis. The elevated number of dormancy-related genes in M. tuberculosis is accounted for, in part at least, by the presence of multiple paralogs that do not exist in M. luteus, indicating that the dormancy machinery of M. luteus is highly minimized compared to that of M. tuberculosis, although it clearly remains fully functional (24, 27, 49, 54, 56, 113, 131, 132, 134).

Conclusion.

The M. luteus genome is very small compared to those of other free-living actinobacteria, raising speculation that this may be connected with both its simple morphology and a restricted ecology. Soil-dwelling organisms typically have a substantial capability for environmental responses mediated through two-component systems and sigma factors, but the M. luteus genome encodes only 14 response regulators and four sigma factors, a finding indicative of adaptation to a rather strict ecological niche. We therefore speculate that its primary adaptation is to (mammalian?) skin, where it is often found, and that its occasional presence elsewhere (water and soil) might possibly arise from contamination by skin flakes. The somewhat minimized nature of the genome may also provide opportunities to evaluate the roles of conserved genes that, in other actinobacteria, are members of substantial paralogous families.

Despite its small size, the M. luteus genome contains an exceptionally high number of transposable elements. These do not seem to have resulted in large-scale genome rearrangements, since the genome sequences for the phylogenetically closest actinobacteria available show only one or two multigene inversions spanning the oriC region, and none that do not include oriC, compared to M. luteus. The possibility remains, however, that some of the transposable elements could have played a part in the contraction of the M. luteus genome from a larger ancestral version. Such elements are present at a number of points of discontinuity between the genomes of M. luteus and its closest characterized relatives (not shown).

The simple morphology of M. luteus is reflected in the absence of nearly all genes known to be concerned with developmental decisions in more complex actinobacteria, and the confinement of genes for cell division and cell wall biosynthesis to a minimal set. The only obvious exception to this is the presence of orthologues of the Streptomyces sporulation genes whiA and whiB, but this is not surprising since whiA orthologues are found in virtually all Gram-positive bacteria, both firmicutes and actinobacteria, and whiB orthologues are nearly universal among actinobacteria. The roles of these two genes in such a simple organism as M. luteus merit exploration. The presence of only a single class A PBP, and only two of class B, may be connected with the adoption of spherical morphology, and with high sensitivity to β-lactams and lysozyme. The well-known sensitivity of M. luteus to diverse other antibiotics may possibly be due to its lack of a wblC gene: this gene confers increased resistance to a wide range of antibiotics and other inhibitors on streptomycetes and mycobacteria, apparently by affecting the expression of a large number of genes that include many predicted to affect resistance (80).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the British Council, the Israeli Ministry of Science and Technology, and the Hebrew University for funding a workshop on the M. luteus genome held on 13 to 18 April 2008 in Jerusalem. For H.R.B. and E.B.G., this study was part of the DOE Joint BioEnergy Institute (http://www.jbei.org) supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Biological and Environmental Research, through contract DE-AC02-05CH11231 between Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and the U.S. Department of Energy. M.Y. thanks the UK BBSRC for financial support, and V.A. and A.S.K. thank the MCB RAS program for financial support.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 30 November 2009.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jb.asm.org/.

The authors have paid a fee to allow immediate free access to this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Albro, P. W. 1971. Confirmation of the identification of the major C-29 hydrocarbons of Sarcina lutea. J. Bacteriol. 108:213-218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]