Abstract

Strains of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium LT2 lacking a functional 2-methylcitric acid cycle (2-MCC) display increased sensitivity to propionate. Previous work from our group indicated that this sensitivity to propionate is in part due to the production of 2-methylcitrate (2-MC) by the Krebs cycle enzyme citrate synthase (GltA). Here we report in vivo and in vitro data which show that a target of the 2-MC isomer produced by GltA (2-MCGltA) is fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase (FBPase), a key enzyme in gluconeogenesis. Lack of growth due to inhibition of FBPase by 2-MCGltA was overcome by increasing the level of FBPase or by micromolar amounts of glucose in the medium. We isolated an fbp allele encoding a single amino acid substitution in FBPase (S123F), which allowed a strain lacking a functional 2-MCC to grow in the presence of propionate. We show that the 2-MCGltA and the 2-MC isomer synthesized by the 2-MC synthase (PrpC; 2-MCPrpC) are not equally toxic to the cell, with 2-MCGltA being significantly more toxic than 2-MCPrpC. This difference in 2-MC toxicity is likely due to the fact that as a si-citrate synthase, GltA may produce multiple isomers of 2-MC, which we propose are not substrates for the 2-MC dehydratase (PrpD) enzyme, accumulate inside the cell, and have deleterious effects on FBPase activity. Our findings may help explain human inborn errors in propionate metabolism.

Humans have used fermentation as an effective method of preservation for a wide variety of foods (41). Today, the weak short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) produced by fermentation, such as acetic, propionic, butyric, and lactic acids, are widely used as food preservatives and in pre- and postharvest agricultural processes (34, 38, 45). Propionate, one of the most abundant SCFAs found in the environment (12), is widely used as a preservative of baked goods in the food industry (38).

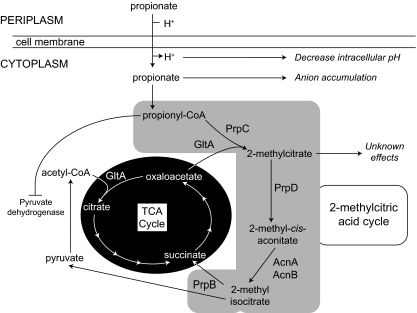

While SCFAs such as propionate are extensively used as food preservatives, our understanding of how microbial growth is prevented by them is incomplete. Early studies argued that growth inhibition either was caused by dissipation of the proton motive force (4, 48) or was due to decreases in intracellular pH (15, 48) or the intracellular accumulation of the propionate anion (46, 47). More recently, the global affects of SCFAs on gene expression (1, 43, 44) and protein synthesis (8, 37, 52, 56) were reported, revealing wide-ranging effects on gene expression in response to propionate in the environment (43). Evidence also suggests that central metabolic processes may be inhibited by SCFAs or their catabolites. An overview of the effects of propionate on the cell can be seen in Fig. 1.

FIG. 1.

Overview of propionate metabolism and toxicity in Salmonella.

Propionyl coenzyme A (Pr-CoA), an intermediate in propionate metabolism, was shown to inhibit pyruvate dehydrogenase in Rhodobacter sphaeroides (40) and Aspergillus niger (10) and competitively inhibit citrate synthase in Escherichia coli (39). 2-Methylcitrate (2-MC), the product of the condensation of oxaloacetate (OAA) and Pr-CoA, was shown to inhibit growth of Salmonella enterica, but the mechanism of action remained unclear (28) (Fig. 1). With such broad negative effects exerted by propionate or its catabolites, the best strategy for microbes to deal with SCFAs such as propionate is to efficiently catabolize them into central metabolites (Fig. 1).

S. enterica, like many other enteric bacteria, is exposed to high levels of propionate in human digestive tracts with total SCFA levels varying from 20 to 300 mM and propionate reaching levels as high as 23.1 mmol/kg (9, 17). To cope with such high concentrations of propionate, this bacterium and other enterobacteria like E. coli utilize the 2-methylcitric acid cycle (2-MCC) to convert propionate to pyruvate (31, 53). In S. enterica, the prpBCDE operon encodes most of the 2-MCC enzymes (30). These genes encode a 2-methylisocitrate lyase (PrpB), a 2-methylcitrate synthase (PrpC), a 2-methylcitrate dehydratase (PrpD), and a propionyl coenzyme A (CoA) synthetase (PrpE) (Fig. 1). Early work with S. enterica showed that insertion elements placed within the prpBCDE operon greatly increased the sensitivity of S. enterica to propionate (23). Strains carrying insertions in prpE, however, were still able to grow on propionate and were not sensitive to propionate because acetyl-CoA synthetase (Acs) compensates for the lack of PrpE (32).

The goal of the studies reported here was to identify a target of 2-MC in S. enterica. Our in vivo and in vitro data support the conclusion that 2-MC inhibits fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase (FBPase), a key enzyme of gluconeogenesis. The inhibition of FBPase blocks the synthesis of glucose, with the concomitant broad negative effects on cell function. We show that while both the 2-MC synthase (PrpC) and citrate synthase (GltA) enzymes synthesize 2-MC, the 2-MC made by GltA (2-MCGltA) is more toxic to the cell than the 2-MC made by PrpC (2-MCPrpC), and we suggest that the reason for this toxicity is due to the difference in stereochemistry of the GltA and PrpC reaction products.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals and culture media.

All chemicals and enzymes were purchased from Sigma unless otherwise stated, except 2-MC, which was purchased from CDN Isotopes (Pointe-Claire, Quebec, Canada). Bacterial cultures were grown in lysogeny broth (LB) (6, 7) for DNA manipulations and in nutrient broth (NB; Difco) for overnight cultures used as inocula. LB medium containing 1.5% Bacto Agar (Difco) was used as solid agar medium where indicated. No-carbon essential (NCE) medium (5) was used as minimal medium supplemented with MgSO4 (1 mM), methionine (0.5 mM), and trace minerals (2, 19). Additional supplements were added as indicated. When used, antibiotics were added to the culture medium at the concentrations in parentheses: ampicillin (100 μg/ml), kanamycin (50 μg/ml), and chloramphenicol (25 μg/ml).

Construction of plasmids and strains.

Strains and plasmids used in this study are shown in Table 1. All DNA-modifying enzymes were purchased from Fermentas unless otherwise stated. Restriction endonuclease SacI was purchased from Promega. All cloning was done in CaCl2 competent Escherichia coli DH5α/F′ (New England Biolabs) using established protocols (33). Plasmids were mobilized into S. enterica strains as follows. Overnight cultures grown from an isolated colony were diluted 1:100 into LB medium supplemented with appropriate antibiotics. Cultures were grown to approximate mid-log phase (optical density at 650 nm [OD650] = 0.6 to 0.8), and 1.5 ml of cell culture was harvested by centrifugation at 18,000 × g in a Beckman Coulter Microfuge 18 centrifuge. Cells were washed three times in 1 ml of ice-cold sterile water and resuspended in 100 μl of water. Plasmids were electroporated into the cells using a Bio-Rad Gene Pulser following manufacturer's instructions.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Genotypea | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial strains | ||

| E. coli | ||

| BL21(λDE3) | F−ompT hsdSB(rB− mB+) dcm gal (DE3) | New England Biolabs |

| DH5α/F′ | F′/endA1 hsdR17(rK− mK+) supE44 thi-1 recA1 gyrA (Nalr) relA1 Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 deoR [φ80dlacD(lacZ)M15] | New England Biolabs |

| S. enterica | ||

| TR6583 | metE205 ara-9 | K. Sanderson via J. Roth |

| Derivatives of TR6583 | ||

| JE2170 | prpC114::MudJ | 23 |

| JE4175 | pBAD30 | Lab collection |

| JE4199 | prpC114::MudJ/pPRP35 | 54 |

| JE4440 | prpC114::MudJ/pBAD30 | 54 |

| JE8431 | ΔprpC134::cat+ | |

| JE8571 | ΔprpC254 | |

| JE10609 | prpC114::MudJ/pFBP2 | |

| JE10713 | iolR1::cat+ | Lab collection |

| JE10831 | prpC114::MudJ ΔiolR1::cat+ | |

| JE11237 | prpC114::MudJ ΔiolR1::cat+fbp121 | |

| JE12230 | ΔprpC254 gltA1182::MudJ | |

| JE12239 | ΔprpC254/pBAD30 | |

| JE12240 | ΔprpC254/pGLTA2 | |

| JE12241 | ΔprpC254 gltA1182::MudJ/pBAD30 | |

| JE12242 | ΔprpC254 gltA1182::MudJ/pGLTA2 | |

| JE12243 | ΔprpC254 gltA1182::MudJ/pPRP35 | |

| JE12246 | ΔprpC254/pPRP35 | |

| JE12516 | prpC114::MudJ/pAMN1 | |

| JE12597 | pAMN1 | |

| JE11377 | prpD126::cat+gltA1182::MudJ | |

| JE11392 | prpD126::cat+gltA1182::MudJ/pPRP35 | |

| JE11393 | prpD126::cat+gltA1182::MudJ/pGLTA2 | |

| JE11394 | prpD126::cat+gltA1182::MudJ/pBAD30 | |

| JE11397 | prpC114::MudJ/pGLTA2 | |

| Plasmids | ||

| pBAD30 | Cloning vector; pACYC184 origin of replication, bla+ (Ampr); expression of the gene of interest under the control of the arabinose-inducible ParaBAD promoter | 22 |

| pFBP2 | fbp+ cloned into pBAD30 | |

| pGLTA2 | gltA+ cloned into pBAD30 | 28 |

| pPRP35 | prpC+ cloned into pBAD30 | 54 |

| pAMN1 | amn+ cloned into pBAD30 |

MudJ is an abbreviation of MudI1734 (13).

Plasmid pFBP2.

The fbp gene of S. enterica was amplified using primers 5′-TAC GGT CGA ATT CCT CCA ATC AAT-3′ and 5′-CAA TGG CGT CTA GAT GCG TTA TTC-3′. The resulting fragment (∼1 kb) was resolved in a 1% agarose gel, extracted from the gel using the QIAquick gel extraction kit (Qiagen), cut with the restriction endonucleases EcoRI and XbaI, and ligated with T4 DNA ligase into vector pBAD30 (22) cut with the same enzymes. The resulting plasmid, pFBP2, was transformed into E. coli DH5α/F′, and cells were plated on LB agar supplemented with ampicillin.

Plasmid pAMN1.

The amn gene of S. enterica was amplified using primers 5′-ATC GAA TGA GCT CCC TCA CCT GTG AAC GCT-3′ and 5′-TAC GCC TCT AGA GCT CCT GTC CAG CAG CAG-3′. The resulting DNA fragment, ∼1.5 kb, was resolved and isolated as described above and cut with restriction endonucleases SacI and XbaI. The resulting DNA fragment was ligated with T4 DNA ligase into vector pBAD30 and transformed into E. coli DH5α/F′. Cells were plated on LB agar supplemented with ampicillin.

Phage P22-dependent transductions.

Transductions were performed using the high-frequency-of-transduction, generalized transducing phage strain P22 HT105 int-201 according to established protocols (14, 19, 49, 50).

Isolation of an fbp allele encoding a variant enzyme that allows a 2-MC synthase (prpC) strain to grow in the presence of propionate.

Localized chemical mutagenesis was performed as previously described (27). Briefly, bacteriophage was grown on strain JE10713 that contained a cat+ cassette replacing iolR (formerly STM4417) (36) located near the fbp gene. Bacteriophage P22 was concentrated at 39,000 × g for 2 h at 4°C in a Beckman Coulter Avanti J-25I centrifuge using a JA-25.50 rotor. Hydroxylamine mutagenesis was monitored by a plaque assay (19) using strain TR6583 as an indicator until a 2-log decrease in the titer of PFU was observed. Recipient strain JE2170 (prpC114::MudJ) was transduced to chloramphenicol resistance using mutagenized bacteriophage as donor. Recombinants were replica printed onto NCE minimal medium plates containing succinate (30 mM) and propionate (10 mM) as carbon and energy sources, kanamycin, and chloramphenicol. Any colonies that grew on minimal medium were retested to confirm the phenotype and reconstructed by bacteriophage P22-mediated transduction, and the fbp allele was sequenced. For the purpose of sequencing fbp, the latter was PCR amplified from each strain using primers 5′-TAC GGT CGA ATT CCT CCA ATC AAT-3′ and 5′-CAA TGG CGT CTA GAT GCG TTA TTC-3′. The amplified fbp fragment was purified by gel extraction using the Qiagen PCR purification kit and sequenced with nonradioactive BigDye protocols (ABI Prism) with the above primers and internal primers 5′-CCG GTC ACC GAA GAA GAT-3′ and 5′-CTT TTT CCG GGA AAC GCA-3′. Sequencing reaction mixtures were purified using the CleanSEQ reaction cleanup procedure (Agencourt Biotechnology) and resolved at the UW-Madison Biotechnology Center.

Preparation and use of cell extracts.

Cell extracts were prepared as follows. Overnight cultures (100 ml) were grown in LB supplemented with kanamycin and chloramphenicol. Cells were harvested by centrifugation in a Beckman Coulter Avanti J-25I centrifuge using a JLA 16.250 rotor at 10,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C. Cells were resuspended in 0.5 ml of HEPES buffer (50 mM, pH 7.5) containing KCl (100 mM). Cells were broken by sonication (50 s, 50% duty, 0.5-s pulses, setting 5) with a 500 sonic dismembrator (Fisher Scientific). Cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 16,100 × g for 25 min in an Eppendorf 5415 D centrifuge at 4°C. Supernatants were then filtered through a 0.45-μm filter (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Filtered cell extracts were dialyzed for 1 h at 4°C against 1 liter of potassium phosphate buffer (10 mM, pH 7.5) containing dithiothreitol (DTT; 1 mM), EDTA (1 mM), and glycerol (20%, vol/vol).

Dialyzed cell extracts were used in reaction mixtures that contained Tris-HCl buffer (100 mM, pH 7.5, at 37°C) containing MgCl2 (10 mM), (NH4)2SO4 (2 mM), EDTA (50 μM), β-mercaptoethanol (5 mM), glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (192 U/mg; 2.5 μg/ml), phosphoglucoisomerase (701 U/mg; 2.5 μg/ml), NADP+ (0.2 mM), and fructose-1,6-bisphosphate (35 μM). Reaction mixtures were preincubated at 37°C for 5 min before the addition of 500 μg of cell extract protein to start the reaction. Reactions were performed in triplicate and were monitored using a Perkin-Elmer Lambda 40 UV/Vis spectrometer at 340 nm; temperature was maintained using a circulating water bath set at 37°C. Data collection and analysis were performed with Perkin-Elmer UV Kinlab software. An extinction coefficient of 6.22 mM−1 cm−1 was used for NADPH (20).

In-frame deletion of prpC.

An in-frame insertion of a chloramphenicol resistance cassette in the prpC gene was constructed using the phage λ Red recombinase as described previously (18). Primers 5′-ATG ACA GAC ACG ACG ATC CTG CAA AAC AAC ACG CAT GTC ATT AAG CCT AAA GTG TAG GCT GGA GCT GCT TC-3′ and 5′-TTA GCA ACG ATC GTC TAT CGA GAC AAA CGG ACG ATC TTC CGG CCC GGT ATA CAT ATG AAT ATC CTC CTT AG-3′ were used to amplify the cat+ gene and to direct the insertion to the prpC gene, resulting in strain JE8431. The insertion was resolved utilizing methods described elsewhere (18); the resulting chloramphenicol-sensitive (Cms) strain was JE8571.

Growth behavior analyses.

We analyzed the growth behavior of strains of interest in liquid NCE medium. Carbon sources utilized were glycerol (10 mM), glucose (0.3 mM), or succinate (30 mM, pH 7.0 at 25°C) with or without propionate (pH 7.0 at 25°C). Strains were grown from single colonies overnight in NB medium supplemented with antibiotic. Fresh medium (196 μl) was inoculated with ∼8 × 106 CFU and grown in 96-well microtiter plates (Becton Dickinson). Growth was monitored in an ELx808 plate reader (Bio-Tek Instruments) at 37°C. Absorbance readings were taken every 15 min at 630 nm with 850 s of shaking between readings; each culture was grown in triplicate. Data were graphed using Prism v4.0 software (GraphPad Software).

RESULTS

2-Methylcitrate causes glucose auxotrophy in S. enterica.

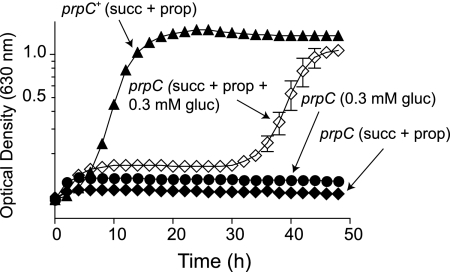

Previous work by others demonstrated that active FBPase was stabilized when citrate was bound to it (25). We hypothesized that if FBPase bound citrate, it might also bind 2-MC, and in so doing, 2-MC might prevent citrate binding, rendering the enzyme unstable. If this idea were true, then S. enterica strains that accumulate 2-MC should have a defect in gluconeogenesis and thus require exogenous glucose to grow. To test this possibility, we grew strain JE2170 (prpC114::MudJ) on succinate (30 mM) and propionate (30 mM), with or without the addition of micromolar amounts of glucose (0.3 mM) to the medium. We predicted that if the accumulation of 2-MC in the cell blocked gluconeogenesis, the addition of glucose would restore growth. In Fig. 2 we show that, while a prpC+ strain (TR6583) grew in medium containing succinate plus propionate as carbon and energy sources, a prpC strain (JE2170) did not. However, the addition of glucose to the medium restored growth of strain JE2170 on succinate plus propionate, albeit after a 30-h lag. The fact that strain JE2170 grew to full density when given small concentrations of glucose suggested that propionate toxicity was, among other things, negatively affecting gluconeogenesis.

FIG. 2.

Glucose circumvents the problem caused by the presence of propionate in the medium. Growth curves were determined in NCE medium. Succinate and propionate were each at 30 mM. A prpC+ strain (closed triangles) grew on succinate plus propionate medium, while a prpC strain (closed diamonds) did not. However, the addition of glucose (0.3 mM) to the medium allowed the prpC strain to grow (open diamonds). The prpC strain did not grow when 0.3 mM glucose was the sole carbon and energy source (closed circles).

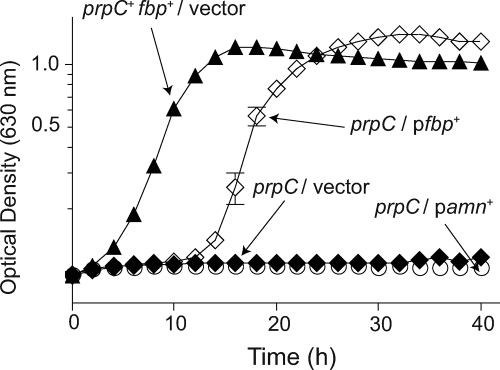

Increased levels of FBPase relieve propionate toxicity.

To investigate whether 2-MC destabilized FBPase, the fbp+ gene was cloned into pBAD30 and the resulting plasmid (pFBP2) was introduced into strain JE2170, yielding strain JE10609. We posited that induction of fbp+ could provide enough FBPase to alleviate the negative effect of 2-MC. Induction of fbp+ expression restored growth of strain JE10609 when low concentrations of propionate (≤5 mM) were present in the medium (Fig. 3) but did not restore growth at higher concentrations of propionate (data not shown). This result was not unexpected, since most likely cells could not produce enough FBPase to match or surpass the intracellular level of 2-MC.

FIG. 3.

Increased levels of FBPase restore growth of a prpC strain in the presence of propionate. Growth curves were determined in NCE medium supplemented with arabinose (10 mM). Carbon/energy sources were succinate (30 mM) and propionate (5 mM). Cells with functional prpC and fbp genes (JE4175, closed triangles) grew, while prpC cells carrying the cloning vector (closed diamonds) or expressing amn (AMP nucleosidase, open circles) did not.

As a control, we expressed a protein that was not involved in gluconeogenesis or propionate metabolism, with the expectation that expression of such a gene should not improve growth of strain JE2170 on succinate plus propionate. In this case, we used the amn gene (encoding AMP nucleosidase), yielding strain JE12516. Expression of amn+ from plasmid pAMN1 did not restore growth on succinate plus propionate (5 mM) (Fig. 3). Additionally, expression of pAMN1 in a wild-type (prp+) background (JE12597) did not result in a decrease in growth, indicating that the lack of growth of JE12516 was not due to increased levels of Amn in the cell (data not shown). These results were consistent with the argument that higher levels of FBPase alleviate the negative effect of 2-MC.

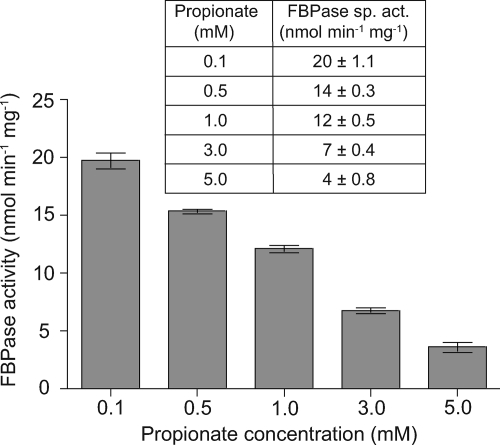

To determine whether FBPase activity was directly affected by the presence of propionate in the medium, cell extracts were prepared from overnight cultures of JE10609 grown in various concentrations of propionate. The specific activity of FBPase in each culture was determined, and the results showed a marked decrease in FBPase activity as a function of increasing propionate concentration in the medium (Fig. 4). These results were consistent with those presented in Fig. 2, where we showed that overexpression of FBPase overcame the negative effects of 2-MC.

FIG. 4.

FBPase activity in cell extracts grown in the presence of propionate. Cell extracts of strain JE10609 (prpC/pfbp+) were prepared from overnight cultures grown in NCE minimal medium supplemented with succinate (30 mM) plus propionate varying from 0.1 mM to 5 mM. Specific activities were measured using 100 μg of cell extract and are reported as nmol min−1 mg−1.

A single amino acid variant of Fbp makes S. enterica resistant to propionate.

To further understand the role of FBPase in propionate toxicity, localized chemical mutagenesis of fbp was performed in an attempt to isolate FBPase variants resistant to 2-MC. Hydroxylamine-mutagenized phage P22 grown on strain JE10713 (iolR1::cat+) was used as donor to transduce strain JE2170 to chloramphenicol resistance. Cmr transductants were screened for strains that could grow on succinate plus propionate. Strains with the latter phenotype were used to grow P22, and the resulting lysate was used to transduce strain JE2170 to chloramphenicol resistance, again screening for growth on succinate plus propionate. Analysis of the fbp gene in the reconstructed strain (JE11237) identified one mutation, which resulted in an S123F substitution. Growth curve analysis of strain JE11237 compared to its isogenic pair (fbp+, JE10831) indicated that strain JE11237 tolerated the presence of propionate, even at high concentrations (Fig. 5). While cultures of strain JE11237 reached full density when grown in the presence of as much as 30 mM propionate, strain JE10831 could not grow in the presence of even 1 mM propionate over the course of the experiment (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

A single amino acid substitution in FBPase confers increased resistance to propionate. Growth curves were determined in NCE minimal medium; carbon and energy sources were succinate (30 mM) and propionate ranging from 30 mM to 1 mM. Strain JE11237 (prpC iolR fbp121 [Fbp(S123F)]) grew in the presence of as much as 30 mM propionate. The control isogenic strain JE10831 (prpC iolR fbp+) was grown under the same conditions as strain JE11237. A no-propionate, succinate-only control is shown to indicate growth rates for the strains when propionate was absent. No significant difference was observed when the strains were grown on succinate.

Biochemical analysis of FBPase activities was performed using cell extracts of strains JE10831 and JE11237. The FbpS123F variant protein was active, but its specific activity was only about 10% of that of the wild-type enzyme (39 ± 3 nmol min−1 mg−1 for JE10831 versus 4 ± 0.3 nmol min−1 mg−1 for JE11237).

2-Methylcitrate synthesized by GltA (2-MCGltA) is more toxic than the 2-methylcitrate synthesized by PrpC (2-MCPrpC).

Experiments were undertaken to determine if there was a connection between the effect of 2-MCGltA and the lack of growth of a prpC strain on succinate plus propionate. Previous work from our laboratory showed that GltA can condense Pr-CoA and OAA to yield 2-MC and that decreased levels of GltA alleviated propionate toxicity (28). At the time, it was unclear whether the observed effect was due to a buildup of 2-MC or whether 2-MC made by GltA was the problem.

We took a genetic approach to distinguish between these possibilities. For this purpose an in-frame deletion of prpC (ΔprpC, strain JE8571) was constructed to allow for the expression of prpD, a downstream gene in the propionate operon and the subsequent biochemical step in the 2-MC cycle. If PrpD used 2-MCGltA as substrate, overproduction of GltA should have no effect on the growth of a ΔprpC strain on succinate plus propionate because the strain would have a functional 2-MC cycle that would convert 2-MCGltA to pyruvate and succinate (29, 31). If PrpD could not use 2-MCGltA, then a ΔprpC strain would not grow, suggesting that 2-MCGltA was probably toxic. Additionally, propionate would not be toxic to a ΔprpC gltA strain (JE12230) because 2-MC could not be synthesized.

Plasmids that carried either prpC+ or gltA+ were introduced into the above-mentioned strains, and the growth behavior of the resulting strains was assessed in medium containing glycerol (10 mM) as carbon and energy source. We used glycerol instead of succinate because the effect of propionate on growth of prp strains is less severe when glycerol is the source of carbon and energy. While prp strains do not grow on succinate plus propionate, they do grow on glycerol plus propionate, albeit with a distinct lag (23).

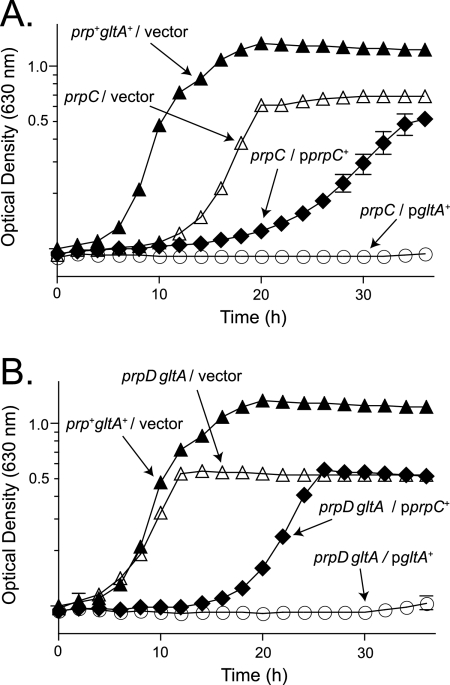

When grown on glycerol plus propionate, a ΔprpC strain harboring a vector control (JE12239) showed a significant lag in growth, while a ΔprpC gltA (JE12241) strain displayed a much less severe lag (Fig. 6A). The decrease in lag of the JE12241 culture was attributed to the absence of 2-MC synthesis in this strain, most likely because in the absence of 2-MC FBPase would not be destabilized, thus allowing the cells to make glucose and grow. As expected, the introduction of plasmid pPRP35 (prpC+) into strain JE12239 (resulting in strain JE12246) and into strain JE12241 (resulting in strain JE12243) lessened the lag to an even greater extent and allowed cells to grow to a higher final density (Fig. 6A). Conversely, in strains JE12240 (ΔprpC/pGLTA2 gltA+) and JE12242 (ΔprpC gltA/pGLTA2 gltA+) the presence of plasmid pGLTA2 prevented growth (Fig. 6B), consistent with the idea that PrpD cannot utilize 2-MCGltA. These results suggested that while 2-MC made by either PrpC or GltA was inhibitory, 2-MCGltA was a more powerful inhibitor.

FIG. 6.

Overexpression of gltA is more toxic than overexpression of prpC. Growth curves were determined in NCE medium supplemented with l-(+)-arabinose (5 mM) and glutamate (5 mM). Carbon sources were glycerol (10 mM) and propionate (30 mM). Strains containing plasmid pPRP35 or pGLTA2 are shown in panels A and B, respectively. A strain carrying a chromosomal in-frame deletion of prpC (ΔprpC) and an empty cloning vector (closed triangles) and a ΔprpC gltA strain carrying an empty vector (open triangles) were used as controls and are shown in both sets of graphs. The ΔprpC/pPRP35 and the ΔprpC gltA/pPRP35 strains are displayed as closed and open diamonds, respectively. The ΔprpC/pGLTA2 and the ΔprpC gltA/pGLTA2 strains are shown as closed and open circles, respectively.

Experiments were performed to block detoxification of 2-MC by PrpD and to determine the relative toxicity of 2-MCPrpC and 2-MCGltA accumulation. Plasmids pPRP35 and pGLTA2 were introduced into the strain harboring a polar insertion in prpC (JE2170), yielding strains JE4199 and JE11397, respectively. When grown on glycerol plus propionate (30 mM), strain JE4199 showed a significant defect in growth compared to the vector control (Fig. 7A). However, strain JE11397 showed an even more severe defect under the same conditions (Fig. 7A).

FIG. 7.

2-MCGltA is more toxic than 2-MCPrpC. Growth curves were determined in NCE medium supplemented with l-(+)-arabinose (5 mM) and glutamate (5 mM). Glycerol (10 mM) and propionate (30 mM) were used as carbon and energy sources. Data in panel A show that an insertion in prpC has polar effects on the expression of prpC and prpD. (A) Overexpression plasmid pPRP35 (prpC+) results in a defect in growth of the strain (closed diamonds) compared to the vector-only control (open triangles), while overexpression of plasmid pGLTA2 (gltA+) blocks growth (open circles). (B) A prpD gltA strain had a growth rate comparable to a wild-type strain (open triangles versus closed triangles). While overexpression of plasmid pPRP35 resulted in a growth defect (closed diamonds), overexpression of plasmid pGLTA2 resulted in a much more severe defect in growth (open circles).

We constructed derivatives of a prpD gltA strain (JE11377) that carried plasmid pPRP35 (prpC+; JE11392) or pGLTA2 (gltA+; JE11393). When grown in minimal medium with glycerol plus propionate as carbon sources, the control strain JE11394 (vector) grew at almost the same rate as JE4175, the wild-type strain carrying the empty cloning vector (Fig. 7B, open versus closed triangles). Introduction of plasmid pPRP35 resulted in a significant defect in growth, while introduction of pGLTA2 blocked growth within the time limits of the experiment (Fig. 7B). These results showed that PrpD did not catabolize 2-MCGltA and that 2-MCGltA was more toxic than 2-MCPrpC.

DISCUSSION

Here we report data supporting conclusions from previous work which suggested that 2-MC, not propionate or propionyl-CoA, is a powerful inhibitor of cell growth. The data reported herein are consistent with the conclusion that 2-MC synthesized by citrate synthase inhibits FBPase, a key enzyme of gluconeogenesis.

FBPase is a target for 2-MC inhibition.

FBPase is a gluconeogenesis-specific enzyme whose activity is regulated by activators and inhibitors, both directly and allosterically. These activators and inhibitors interconvert the FBPase homotetramer between its active R state and inactive T state (25, 57). Specific allosteric inhibitors of FBPase include AMP (51), glucose 6-phosphate (26), and 5-amino-4-imidazole carboxamide ribotide (AICAR) (21). Activators include phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP), citrate, and sulfate ions (24, 25). The fact that 2-MC inhibits FBPase is not surprising since citrate functions allosterically to stabilize the active R state of FBPase, preventing the conversion of the tetramer to an inactive form (25). While the structural similarities between 2-MC and citrate may allow 2-MC to bind to FBPase, the stereochemical properties of 2-MC may ultimately inhibit FBPase activity. In-depth mechanistic studies are needed to determine if this is the case.

That the S123F substitution in FBPase allowed a ΔprpC strain of S. enterica to grow in the presence of propionate was a surprising result because residue S123 is neither near the citrate-binding site nor near the active site of the enzyme. At present we do not understand how the S123F substitution might prevent the inhibitory effects of 2-MC, but we suspect that it might not be a direct effect on citrate binding or substrate binding. Residue S123 does appear to be on the C-1-C-2/C-3-C-4 interfaces of the FBPase tetramer and could possibly affect the ability of FBPase to interconvert between the active R state and inactive T state. The FBPaseS123F protein had only 10% of the activity of the wild-type FBPase and was less stable. Here again, additional studies are needed to understand the effect of the S123F substitution on the activity of FBPase and how it might relieve the inhibitory effects of 2-MC.

Not all 2-MCs are equally inhibitory.

The data show that the severity of the 2-MC toxicity correlates with its source. It is known that citrate synthase (GltA) synthesizes 2-MC and that a buildup of 2-MC in the cell inhibits growth (28). The experiments shown here indicate that the 2-MC synthesized by GltA (2-MCGltA) has stronger inhibitory effects than the 2-MC synthesized by PrpC (2-MCPrpC). One explanation for this observation is that the S. enterica GltA enzyme is a si-citrate synthase, which synthesizes three different isomers of 2-MC (2S,3S; 2S,3R; and 2R,3S) when propionyl-CoA and oxaloacetate serve as substrates (55). PrpC, on the other hand, synthesizes a single 2-MC isomer (2S,3S) (11). This fact helps us understand why a strain containing an in-frame deletion of prpC fails to grow when gltA is overexpressed but can grow when prpC is overexpressed (Fig. 5). PrpD, the 2-MC dehydratase, is also a stereospecific enzyme, utilizing only the (2S,3S)-2-MC isomer (11). The (2S,3R) and the (2R,3S) isomers of 2-MC produced by GltA could build up to levels that become inhibitory to the cell. If the 2-MCGltA isomers accumulate inside the cell, it would provide a rationale for why one or more of the 2-MCGltA isomers is a stronger inhibitor of cell growth than 2-MCPrpC.

What is the meaning of the observed lag?

We can only speculate on this issue. At present, we suspect that the observed lag may reflect on additional negative effects of 2-MCGltA on as-yet-unidentified processes. Because the cell eventually recovers from these effects (as long as the glucose is provided), we suggest that, whatever the response the cell mounts to solve other problems caused by 2-MCGltA, it takes time. We have isolated additional propionate-resistant strains with lesions in loci other than fbp whose function appears to be targets of 2-MCGltA. We are currently trying to establish the identity of these loci.

Our results may shed light on human inborn errors in propionate metabolism.

In humans, propionate is catabolized via the methylmalonyl-CoA mutase pathway, not via the 2-methylcitric acid cycle. In the former pathway, propionyl-CoA is converted to succinyl-CoA by carboxylation, isomerization, and a C skeleton rearrangement. The product of the pathway, succinyl-CoA, is an intermediate of the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle and is readily metabolized by the cell. Mutations affecting the carboxylase function of the methylmalonyl-CoA pathway lead to propionic acidemia, an often-fatal metabolic disorder. Interestingly, reports in the literature show that patients with a deficiency in propionyl-CoA carboxylase accumulate 2-MC in their urine and cerebrospinal and amniotic fluids (3, 16, 35, 42). Conclusions drawn from our work suggest that in patients deficient in propionyl-CoA carboxylase, 2-MC is synthesized by the citrate synthase enzyme, leading to broad negative effects and eventually cell death.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by PHS grant R21-AI082916 to J.C.E.-S.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 30 November 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arnold, C. N., J. McElhanon, A. Lee, R. Leonhart, and D. A. Siegele. 2001. Global analysis of Escherichia coli gene expression during the acetate-induced acid tolerance response. J. Bacteriol. 183:2178-2186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balch, W. E., and R. S. Wolfe. 1976. New approach to the cultivation of methanogenic bacteria: 2-mercaptoethanesulfonic acid (HS-CoM)-dependent growth of Methanobacterium ruminantium in a pressurized atmosphere. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 32:781-791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ballhausen, D., L. Mittaz, O. Boulat, L. Bonafe, and O. Braissant. 2009. Evidence for catabolic pathway of propionate metabolism in CNS: expression pattern of methylmalonyl-CoA mutase and propionyl-CoA carboxylase alpha-subunit in developing and adult rat brain. Neuroscience 164:578-587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baronofsky, J. J., W. J. Schreurs, and E. R. Kashket. 1984. Uncoupling by acetic acid limits growth of and acetogenesis by Clostridium thermoaceticum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 48:1134-1139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berkowitz, D., J. M. Hushon, H. J. Whitfield, Jr., J. Roth, and B. N. Ames. 1968. Procedure for identifying nonsense mutations. J. Bacteriol. 96:215-220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bertani, G. 2004. Lysogeny at mid-twentieth century: P1, P2, and other experimental systems. J. Bacteriol. 186:595-600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bertani, G. 1951. Studies on lysogenesis. I. The mode of phage liberation by lysogenic Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 62:293-300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blankenhorn, D., J. Phillips, and J. L. Slonczewski. 1999. Acid- and base-induced proteins during aerobic and anaerobic growth of Escherichia coli revealed by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis. J. Bacteriol. 181:2209-2216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bohnhoff, M., C. P. Miller, and W. R. Martin. 1964. Resistance of the mouse's intestinal tract to experimental Salmonella infection. I. Factors which interfere with the initiation of infection by oral inoculation. J. Exp. Med. 120:805-816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brock, M., and W. Buckel. 2004. On the mechanism of action of the antifungal agent propionate. Eur. J. Biochem. 271:3227-3241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brock, M., C. Maerker, A. Schutz, U. Völker, and W. Buckel. 2002. Oxidation of propionate to pyruvate in Escherichia coli. Involvement of methylcitrate dehydratase and aconitase. Eur. J. Biochem. 269:6184-6194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buckel, W. 1999. Anaerobic energy metabolism, p. 278-326. In J. W. Lengler, G. Drews, and H. G. Chlegel (ed.), Biology of the procaryotes. Thieme, Stuttgart, Germany.

- 13.Castilho, B. A., P. Olfson, and M. J. Casadaban. 1984. Plasmid insertion mutagenesis and lac gene fusion with mini-mu bacteriophage transposons. J. Bacteriol. 158:488-495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chan, R. K., D. Botstein, T. Watanabe, and Y. Ogata. 1972. Specialized transduction of tetracycline resistance by phage P22 in Salmonella typhimurium. II. Properties of a high-frequency-transducing lysate. Virology 50:883-898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cole, M. B., and M. H. Keenan. 1986. Synergistic effects of weak-acid preservatives and pH on the growth of Zygosaccharomyces bailii. Yeast 2:93-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cornejo, V., M. Colombo, G. Duran, P. Mabe, M. Jimenez, A. De la Parra, A. Valiente, and E. Raimann. 2002. Diagnosis and follow up of 23 children with organic acidurias. Rev. Med. Chil. 130:259-266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cummings, J. H., E. W. Pomare, W. J. Branch, C. P. Naylor, and G. T. Macfarlane. 1987. Short chain fatty acids in human large intestine, portal, hepatic and venous blood. Gut 28:1221-1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Datsenko, K. A., and B. L. Wanner. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:6640-6645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davis, R. W., D. Botstein, and J. R. Roth. 1980. A manual for genetic engineering: advanced bacterial genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 20.Dawson, R. M. C., D. C. Elliott, W. H. Elliott, and K. M. Jones. 1986. Data for biochemical research, 3rd ed. Oxford University Press, Oxford, United Kingdom.

- 21.Dougherty, M. J., J. M. Boyd, and D. M. Downs. 2006. Inhibition of fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase by aminoimidazole carboxamide ribotide prevents growth of Salmonella enterica purH mutants on glycerol. J. Biol. Chem. 281:33892-33899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guzman, L. M., D. Belin, M. J. Carson, and J. Beckwith. 1995. Tight regulation, modulation, and high-level expression by vectors containing the arabinose PBAD promoter. J. Bacteriol. 177:4121-4130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hammelman, T. A., G. A. O'Toole, J. R. Trzebiatowski, A. W. Tsang, D. Rank, and J. C. Escalante-Semerena. 1996. Identification of a new prp locus required for propionate catabolism in Salmonella typhimurium LT2. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 137:233-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hines, J. K., H. J. Fromm, and R. B. Honzatko. 2006. Novel allosteric activation site in Escherichia coli fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase. J. Biol. Chem. 281:18386-18393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hines, J. K., H. J. Fromm, and R. B. Honzatko. 2007. Structures of activated fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase from Escherichia coli. Coordinate regulation of bacterial metabolism and the conservation of the R-state. J. Biol. Chem. 282:11696-11704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hines, J. K., C. E. Kruesel, H. J. Fromm, and R. B. Honzatko. 2007. Structure of inhibited fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase from Escherichia coli: distinct allosteric inhibition sites for AMP and glucose 6-phosphate and the characterization of a gluconeogenic switch. J. Biol. Chem. 282:24697-24706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hong, J. S., and B. N. Ames. 1971. Localized mutagenesis of any specific small region of the bacterial chromosome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 68:3158-3162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Horswill, A. R., A. R. Dudding, and J. C. Escalante-Semerena. 2001. Studies of propionate toxicity in Salmonella enterica identify 2-methylcitrate as a potent inhibitor of cell growth. J. Biol. Chem. 276:19094-19101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Horswill, A. R., and J. C. Escalante-Semerena. 2001. In vitro conversion of propionate to pyruvate by Salmonella enterica enzymes: 2-methylcitrate dehydratase (PrpD) and aconitase enzymes catalyze the conversion of 2-methylcitrate to 2-methylisocitrate. Biochemistry 40:4703-4713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Horswill, A. R., and J. C. Escalante-Semerena. 1997. Propionate catabolism in Salmonella typhimurium LT2: two divergently transcribed units comprise the prp locus at 8.5 centisomes, prpR encodes a member of the sigma-54 family of activators, and the prpBCDE genes constitute an operon. J. Bacteriol. 179:928-940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Horswill, A. R., and J. C. Escalante-Semerena. 1999. Salmonella typhimurium LT2 catabolizes propionate via the 2-methylcitric acid cycle. J. Bacteriol. 181:5615-5623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Horswill, A. R., and J. C. Escalante-Semerena. 1999. The prpE gene of Salmonella typhimurium LT2 encodes propionyl-CoA synthetase. Microbiology 145:1381-1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Inoue, H., H. Nojima, and H. Okayama. 1990. High efficiency transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. Gene 96:23-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kabara, J. J., and T. Eklund. 1991. Organic acids and esters, p. 45-71. In N. J. Russell and G. W. Gould (ed.), Food preservatives. Glasgow Blachie, New York, NY.

- 35.Kretschmer, R. E., and C. Bachmann. 1988. Methylcitric acid determination in amniotic fluid by electron-impact mass fragmentography. J. Clin. Chem. Clin. Biochem. 26:345-348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kroger, C., and T. M. Fuchs. 2009. Characterization of the myo-inositol utilization island of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 191:545-554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lambert, L. A., K. Abshire, D. Blankenhorn, and J. L. Slonczewski. 1997. Proteins induced in Escherichia coli by benzoic acid. J. Bacteriol. 179:7595-7599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lück, E., and M. Jager. 1997. Propionic acid, antimicrobial food additives: characteristics, uses, and effects, 2nd ed. Springer, New York, NY.

- 39.Man, W.-J., Y. Li, C. D. Connor, and D. C. Wilton. 1995. The binding of propionyl-CoA and carboxymethyl-CoA to Escherichia coli citrate synthase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1250:69-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maruyama, K., and H. Kitamura. 1985. Mechanisms of growth inhibition by propionate and restoration of the growth by sodium bicarbonate or acetate in Rhodopseudomonas sphaeroides S. J. Biochem. 98:819-824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ohmomo, S., O. Tanaka, H. K. Kitamoto, and Y. Cai. 2002. Silage and microbial performance, old story but new problems. Jpn. Agric. Res. Q. 36:59-71. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Perez-Cerda, C., B. Merinero, M. Marti, J. C. Cabrera, L. Pena, M. J. Garcia, J. Gangoiti, P. Sanz, P. Rodriguez-Pombo, J. Hoenicka, E. Richard, S. Muro, and M. Ugarte. 1998. An unusual late-onset case of propionic acidaemia: biochemical investigations, neuroradiological findings and mutation analysis. Eur. J. Pediatr. 157:50-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Polen, T., D. Rittmann, V. F. Wendisch, and H. Sahm. 2003. DNA microarray analyses of the long-term adaptive response of Escherichia coli to acetate and propionate. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:1759-1774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pomposiello, P. J., M. H. Bennik, and B. Demple. 2001. Genome-wide transcriptional profiling of the Escherichia coli responses to superoxide stress and sodium salicylate. J. Bacteriol. 183:3890-3902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ricke, S. C. 2003. Perspectives on the use of organic acids and short chain fatty acids as antimicrobials. Poult. Sci. 82:632-639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Roe, A. J., D. McLaggan, I. Davidson, C. O'Byrne, and I. R. Booth. 1998. Perturbation of anion balance during inhibition of growth of Escherichia coli by weak acids. J. Bacteriol. 180:767-772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Russell, J. B., and F. Diez-Gonzalez. 1998. The effects of fermentation acids on bacterial growth. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 39:205-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Salmond, C. V., R. G. Kroll, and I. R. Booth. 1984. The effect of food preservatives on pH homeostasis in Escherichia coli. J. Gen. Microbiol. 130:2845-2850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schmieger, H. 1971. A method for detection of phage mutants with altered transducing ability. Mol. Gen. Genet. 110:378-381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schmieger, H., and H. Backhaus. 1973. The origin of DNA in transducing particles in P22-mutants with increased transduction-frequencies (HT-mutants). Mol. Gen. Genet. 120:181-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sedivy, J. M., J. Babul, and D. G. Fraenkel. 1986. AMP-insensitive fructose bisphosphatase in Escherichia coli and its consequences. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 83:1656-1659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stancik, L. M., D. M. Stancik, B. Schmidt, D. M. Barnhart, Y. N. Yoncheva, and J. L. Slonczewski. 2002. pH-dependent expression of periplasmic proteins and amino acid catabolism in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 184:4246-4258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Textor, S., V. F. Wendisch, A. A. De Graaf, U. Muller, M. I. Linder, D. Linder, and W. Buckel. 1997. Propionate oxidation in Escherichia coli: evidence for operation of a methylcitrate cycle in bacteria. Arch. Microbiol. 168:428-436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tsang, A. W., A. R. Horswill, and J. C. Escalante-Semerena. 1998. Studies of regulation of expression of the propionate (prpBCDE) operon provide insights into how Salmonella typhimurium LT2 integrates its 1,2-propanediol and propionate catabolic pathways. J. Bacteriol. 180:6511-6518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.van Rooyen, J. P., L. J. Mienie, E. Erasmus, W. J. De Wet, D. Ketting, M. Duran, and S. K. Wadman. 1994. Identification of the stereoisomeric configurations of methylcitric acid produced by si-citrate synthase and methylcitrate synthase using capillary gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 17:738-747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yohannes, E., D. M. Barnhart, and J. L. Slonczewski. 2004. pH-dependent catabolic protein expression during anaerobic growth of Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 186:192-199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang, Y., J. Y. Liang, S. Huang, and W. N. Lipscomb. 1994. Toward a mechanism for the allosteric transition of pig kidney fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase. J. Mol. Biol. 244:609-624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]