Abstract

Loss of expression of the type III transforming growth factor-β receptor (TβRIII or betaglycan), a transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) superfamily co-receptor, is common in human breast cancers. TβRIII suppresses cancer progression in vivo by reducing cancer cell migration and invasion by largely unknown mechanisms. Here, we demonstrate that the cytoplasmic domain of TβRIII is essential for TβRIII-mediated downregulation of migration and invasion in vitro and TβRIII-mediated inhibition of breast cancer progression in vivo. Functionally, the cytoplasmic domain of TβRIII is required to attenuate TGF-β signaling, whereas TβRIII-mediated attenuation of TGF-β signaling is required for TβRIII-mediated inhibition of migration and invasion. Mechanistically, both TβRIII-mediated inhibition of TGF-β signaling and TβRIII-mediated inhibition of invasion occur through the interaction of the cytoplasmic domain of TβRIII with the scaffolding protein GAIP-interacting protein C-terminus (GIPC). Taken together, these studies support a functional role for the TβRIII cytoplasmic domain interacting with GIPC to suppress breast cancer progression.

Introduction

Transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) is a member of a superfamily of cytokines involved in regulating and mediating a variety of normal and pathological processes, including wound healing, fibrosis and cancer progression (1,2). TGF-β signaling is initiated by the binding of TGF-β ligand to cell surface receptors. TGF-β binds either to the type III transforming growth factor-β receptor (TβRIII), which in turn presents TGF-β to the dimeric type II transforming growth factor-β receptor (TβRII) or directly to TβRII. Ligand binding to TβRII leads to recruitment of the type I transforming growth factor-β receptor (TβRI). TβRII then activates TβRI in the cytoplasmic domain, activating TβRI kinase activity. Subsequently, TβRI phosphorylates a receptor Smad, either Smad2/3 or Smad1/5/8. The phosphorylated receptor Smads bind to Smad4, and the consequent complex accumulates in the nucleus and regulates transcription of TGF-β-responsive genes in a cell- and context-specific manner (3).

In normal mammary epithelial cells, TGF-β functions in ductal and glandular development as an inhibitor of proliferation (4). In mammary carcinogenesis, TGF-β initially acts as a tumor suppressor as supported by murine models in which overexpressing TGF-β suppresses tumor formation (5) and a chemically induced breast cancer mouse model in which overexpressing dominant-negative TβRII enhances tumor progression (6). Throughout breast cancer development, however, cells become increasingly resistant to the antiproliferative effects of TGF-β, and TGF-β then functions as a tumor promoter. Indeed, dominant-negative TβRII decreased lung metastatic potential in oncogenic Neu mice, whereas targeted expression of activated TβRI in the mammary glands increased lung metastases (7).

While mutations in the TGF-β pathway are rare in human breast cancer, changes in expression of specific pathway components can contribute to breast cancer progression. For example, loss of TβRII expression correlates with high tumor grade and tumor invasiveness in early cancer progression (8,9), whereas in later stages, increased TGF-β levels in breast cancer patients correlate with poor prognosis (10). In addition, we have previously identified TβRIII as an important suppressor of breast cancer progression, with frequent loss of TβRIII expression during breast cancer progression and shorter time to recurrence in breast cancer patients with decreased TβRIII levels. Restoring TβRIII expression was sufficient to inhibit breast cancer cell migration and invasion in vitro and breast cancer invasion and metastasis in vivo (11). Importantly, these effects on migration, invasion and tumor progression are not confined to breast cancer but have also been demonstrated in non-small cell lung, ovarian, pancreatic and prostate cancer models (12–15).

Mechanistically, TβRIII appears to function as a suppressor of cancer progression through several discrete mechanisms. We have demonstrated that cell surface TβRIII undergoes ectodomain shedding, releasing the soluble extracellular domain, which can sequester TGF-β ligand to inhibit TGF-β signaling and inhibit invasion in breast cancer models in vitro and lung metastasis in vivo (11). TβRIII also inhibits cancer cell migration through interacting with the scaffolding protein β-arrestin2 to activate Cdc42 and reduce directional persistence of cancer cells (16).

The cytoplasmic domain of TβRIII is a relatively short region with no known intrinsic kinase activity. However, it is important in modulating TβRIII expression and in mediating downstream signaling. TβRII phosphorylates TβRIII's cytoplasmic domain at Thr841, resulting in β-arrestin2 binding (17). This interaction is important for TβRIII internalization and ultimately leads to downregulation of TGF-β signaling. In addition, the adapter protein GAIP-interacting protein C-terminus (GIPC) binds to the PDZ-binding domain located at the terminal three amino acids of TβRIII. Depending on cellular context, the interaction of GIPC with TβRIII can either upregulate or downregulate cell surface expression (18). In terms of signaling, evidence suggests that the cytoplasmic domain is critical in mediating downstream Smad signaling of TGF-β2 (19). In addition, modulation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling by TβRIII has been shown to depend on an intact cytoplasmic domain, independent of Smad signaling (20,21). These findings suggest that the cytoplasmic tail is important in the regulation of the expression of TβRIII at the cell surface and plays a role in mediating both Smad-dependent and Smad-independent signaling. Accordingly, here we examine the contribution of the cytoplasmic domain of TβRIII in mediating the suppressor of cancer progression role of TβRIII in vitro and in vivo.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and reagents

4T1 cells stably transfected with the luciferase gene under puromycin selection were generously provided by M.W.Dewhirst (Duke University). Antibodies used were phospho-p65 (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), inhibitor of kappa B (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), pSmad2 (Cell Signaling Technology), total Smad2 (Cell Signaling Technology), TβRIII (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) and GIPC1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). shGIPC1 plasmid was generously provided by J.C.Rathmell (Duke University) (22). SB431542 was obtained from Sigma (St Louis, MO).

Immunoblotting

Cells were plated overnight, serum starved for 4 h and stimulated for 20 min at varying doses of TGF-β. Lysates were harvested with hot sample buffer and boiled for 5 min. Lysates were separated using sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gels, transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes, blocked in 5% milk in phosphate-buffered saline/Tween and incubated overnight at 4°C with gentle agitation.

Fibronectin migration and Matrigel invasion assays

Fibronectin (Calbiochem, Gibbstown, NJ) was coated on transwells (Costar, Lowell, MA) at a concentration of 50 μg/ml in serum-free Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM), whereas Matrigel transwells (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) were preincubated with serum-free DMEM for 2 h at 37°C. For migration assays, 50 000 cells were plated in 200 μl of serum-free DMEM in the upper chamber; for invasion assays, 200 000 cells were plated in 200 μl of serum-free DMEM and allowed to migrate for 24 h toward 600 μl of 10% fetal bovine serum in DMEM. Cells on the upper surface were scraped with a cotton swab and wells were stained with three-Step Stain Kit (Richard-Allan Scientific, Kalamazoo, MI). Filters were then mounted on microscope slides with Vectamount (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Three random fields on each filter were counted. Cells were plated in duplicate, and each experiment was conducted at least three times.

In vivo metastasis

Animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Duke University. Empty vector pcDNA3.1-neo, TβRIII and TβRIII-cyto lines were generated by transfecting 4T1 cells with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), further selected with G418 and confirmed by 125I-TGF-β binding and cross-linking as described previously (11). A total of 25 000 cells were injected into the right axillary mammary fat pad of 6-week-old virgin female Balb/c mice, using 15 mice in each group. After 12 days, the resulting primary tumors were excised, weighed and measured with calipers (volume calculated by 0.52 × length × width2). Bioluminescent imaging with intraperitoneal injections of 150 μg/g luciferin (Xenogen, Hopkinton, MA) was conducted with an IVIS camera (Xenogen) every 3 days for 24 days. Regions of interest were defined automatically, and luciferase units are expressed as photons/s/cm2/steradian. Background signal was defined by imaging a mouse without luciferin. Mice were killed at the end of the study, organs visually inspected, and samples of interest preserved for immunohistochemical analysis.

Immunohistochemistry

Tissue samples were formalin fixed, paraffin embedded and cut onto microscope slides. Slides were then either stained for hematoxylin and eosin or prepared for immunohistochemical analysis. Staining for terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated deoxyuridine triphosphate nick end labeling (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) and proliferating cell nuclear antigen (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was performed according to manufacturer's instructions. Phospho-Smad2 staining (Cell Signaling Technology) was performed following antigen retrieval by boiling in Tris–ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (10 mM Tris, 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid and 0.05% Tween, pH 9.0) for 5 min.

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as mean ± SEM. Two-tailed Student's t-test was performed. P-values of <0.05 were considered significant.

Results

TβRIII's cytoplasmic domain has a role in TβRIII-mediated inhibition of breast cancer cell migration and invasion

We have previously demonstrated a role for TβRIII in inhibiting breast cancer metastases in vivo and cancer cell migration and invasion in vitro (11). The cytoplasmic domain of TβRIII has a critical role in regulating TβRIII cell surface expression and endocytosis through its interaction with GIPC (18) and β-arrestin2 (17). The cytoplasmic domain is also important in mediating TβRIII-dependent downstream signaling to both Smad-dependent (3,19,23) and Smad-independent signaling pathways (20,24,25). Accordingly, to further define the mechanism by which TβRIII suppresses breast cancer progression, we investigated the specific contribution of the cytoplasmic domain of TβRIII in the 4T1 syngeneic murine model of mammary carcinogenesis.

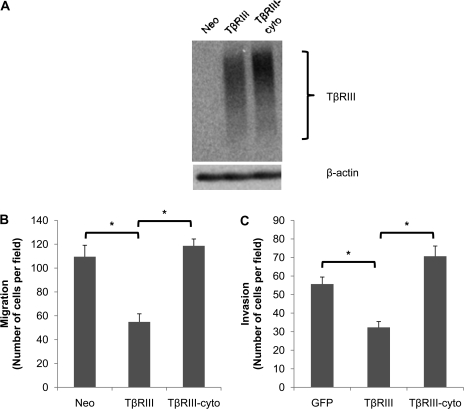

Full-length TβRIII (TβRIII), TβRIII lacking the cytoplasmic domain (TβRIII-cyto) or empty vector (Neo) was stably expressed in the 4T1 cell line (Figure 1A). While TβRIII inhibited migration by ∼50% (Figure 1B), consistent with our prior results (11), TβRIII-cyto failed to inhibit the migration of 4T1 cells (Figure 1B). In addition, while TβRIII expression inhibited invasion by ∼40%, TβRIII-cyto expression failed to inhibit invasion (Figure 1C). Interestingly, TβRIII-cyto slightly enhanced the invasive potential of 4T1 cells in comparison with the negative control (Figure 1C), although these results were not significantly different. These results suggest an important role for the cytoplasmic domain of TβRIII in TβRIII-mediated inhibition of breast cancer cell migration and invasion.

Fig. 1.

The cytoplasmic domain of TβRIII has a role in TβRIII-mediated inhibition of breast cancer cell migration and invasion. (A) TβRIII expression in 4T1 stable cell lines. 4T1 cells were transfected with empty vector control (Neo), full-length TβRIII (TβRIII) or TβRIII lacking the cytoplasmic domain (TβRIII-cyto), selected by growth in G418 (600 μg/ml) and pools of resistant colonies selected. Cells were subjected to 125I-TGF-β binding and cross-linking to examine TβRIII expression, with β-actin as loading control. (B) 4T1-Neo, TβRIII or TβRIII-cyto were plated on fibronectin transwells and allowed to migrate for 24 h toward media with 10% fetal bovine serum. (C) 4T1 cells were infected with adenoviral green fluorescent protein (GFP), full-length TβRIII or TβRIII-cyto for 48 h, washed and plated on Matrigel inserts. Cells were allowed to invade for 24 h toward media with 10% fetal bovine serum. Counts of three random fields were averaged and representative data of three independent experiments are shown; *P < 0.05.

TβRIII's cytoplasmic domain contributes to TβRIII-mediated inhibition of migration and invasion by inhibiting TGF-β signaling

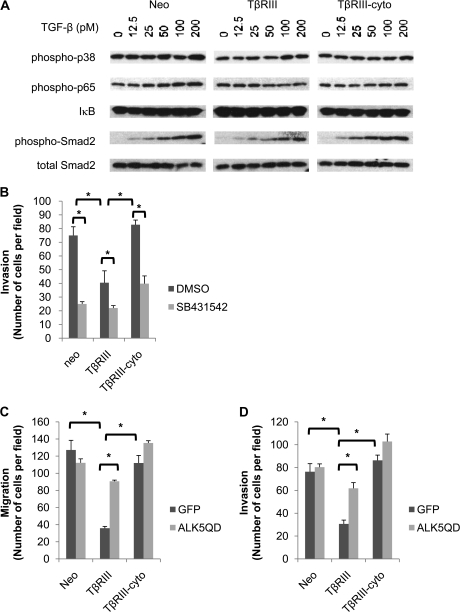

Given TβRIII's known role in regulating TGF-β signaling, the contribution of the cytoplasmic domain of TβRIII to TGF-β signaling was examined. 4T1 cells stably expressing TβRIII, TβRIII-cyto or empty vector were stimulated with TGF-β and analyzed for activation of pathways known to be downstream of TGF-β and TβRIII, including the Smad2 (3), p38 (20,21) and nuclear factor-kappaB (24,25) pathways. While TβRIII expression decreased TGF-β-mediated Smad2 phosphorylation, TβRIII-cyto expression had no effect (Figure 2A, supplementary Figure 5A is available at Carcinogenesis Online). In contrast, activation of the nuclear factor-kappaB signaling pathway, as assessed by phosphorylation of p65 or inhibitor of kappa B levels, or p38 signaling, as assessed by phosphorylation of p38, was not differentially regulated by TβRIII and TβRIII-cyto (Figure 2A), suggesting a specific role for cytoplasmic domain of TβRIII in negatively regulating TGF-β signaling.

Fig. 2.

The cytoplasmic domain of TβRIII has a role in TβRIII-mediated inhibition of TGF-β signaling. (A) 4T1 cells stably transfected with TβRIII, TβRIII-cyto or empty vector (Neo) were serum starved for 4 h, treated with the indicated doses of TGF-β for 20 min and subjected to western blot analysis with the indicated antibodies. (B) 4T1-Neo, TβRIII or TβRIII-cyto cells were preincubated with either vehicle [dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)] or the ALK5 inhibitor SB431542 (20 μM) for 20 min prior to plating on Matrigel transwells and allowed to invade for 24 h. Counts of three random fields were averaged and representative data of three independent experiments are shown. (C and D) 4T1-Neo, TβRIII or TβRIII-cyto cells were infected with either adenoviral green fluorescent protein (GFP) or a constitutively active ALK5 mutant (ALK5QD) for 48 h, plated on transwells and incubated for 24 h. Counts of three random fields were averaged and representative data of three independent experiments are shown; *P < 0.05.

To investigate whether the effects of TβRIII in inhibiting breast cancer cell migration and invasion might be through TβRIII-mediated attenuation of TGF-β signaling, we directly assessed the effect of altering TGF-β signaling on breast cancer cell migration and invasion. Consistent with a role for inhibition of TGF-β signaling directly inhibiting TGF-β signaling with the ALK5 pharmacological inhibitor SB431542 inhibited the migration of Neo and TβRIII-cyto to the same extent as TβRIII (Figure 2B). If TβRIII inhibits migration and invasion by inhibiting TGF-β signaling, we hypothesized that activating TGF-β signaling downstream of TβRIII utilizing constitutively active TβRI (ALK5QD) might bypass this inhibition. Consistent with this hypothesis, while ALK5QD expression had minimal effect on the migration or invasion of 4T1-Neo and 4T1-TβRIII-cyto cells (Figure 2C and D), ALK5QD expression significantly attenuated TβRIII-mediated inhibition of migration (Figure 2C) and invasion (Figure 2D). Taken together, these data support a role for TβRIII-mediated inhibition of TGF-β signaling in TβRIII-mediated inhibition of migration and invasion.

The interaction of TβRIII with GIPC is required for TβRIII-mediated suppression of TGF-β signaling and invasion

As TβRIII-mediated inhibition of TGF-β signaling appears to have a predominant role in TβRIII-mediated inhibition of migration and invasion, we further investigated the mechanism of TβRIII action. TβRIII undergoes ectodomain shedding to release the soluble extracellular domain, soluble TβRIII (sTβRIII), which can function to bind and sequester ligand and can also inhibit breast cancer invasion (11,26). We initially investigated whether TβRIII and TβRIII-cyto differed in their ability to produce sTβRIII. Examining the conditioned media from 4T1-TβRIII and 4T1-TβRIII-cyto revealed that both TβRIII and TβRIII-cyto were shed to a similar extent (supplementary Figure 1A is available at Carcinogenesis Online). As the sTβRIII produced by TβRIII and TβRIII-cyto might function to differentially inhibit breast cancer migration or invasion, we examined the ability of conditioned media from 4T1-TβRIII and 4T1-TβRIII-cyto cells to inhibit 4T1 cell migration. Consistent with our prior results (11), conditioned media from TβRIII and TβRIII-cyto both inhibited 4T1 cell migration to a similar extent (supplementary Figure 1B is available at Carcinogenesis Online), further supporting that differential shedding was not responsible for differences in TβRIII-mediated inhibition of TGF-β signaling, migration and invasion between TβRIII and TβRIII-cyto.

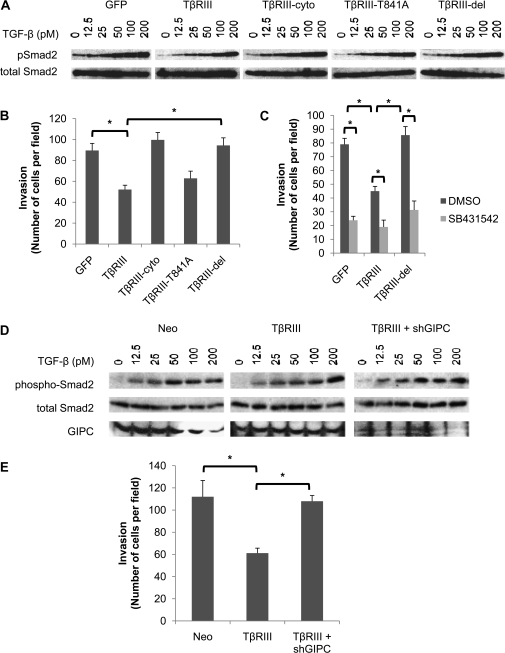

We next investigated the contribution of specific previously defined TβRIII cytoplasmic domain functions, namely the interactions with scaffolding proteins GIPC and β-arrestin2. TβRIII mutants unable to bind β-arrestin2 (TβRIII-T841A) or GIPC (TβRIII-del, lacking three C-terminal amino acids) were expressed in 4T1 cells alongside with TβRIII and TβRIII-cyto (supplementary Figure 2 is available at Carcinogenesis Online). Consistent with our prior results (Figure 2A), TβRIII inhibited TGF-β signaling, whereas TβRIII-cyto did not (Figure 3A, supplementary Figure 5B is available at Carcinogenesis Online). Interestingly, while TβRIII-T841A also inhibited TGF-β signaling (Figure 3A, supplementary Figure 5B is available at Carcinogenesis Online), TβRIII-del was completely unable to inhibit TGF-β signaling (Figure 3A, supplementary Figure 5B is available at Carcinogenesis Online), suggesting a specific role for this region of the cytoplasmic domain of TβRIII in inhibiting TGF-β signaling. To investigate the contribution of interactions with GIPC and β-arrestin2 on breast cancer invasion, we expressed TβRIII, TβRIII-cyto, TβRIII-T841A or TβRIII-del in 4T1 cells. Again, TβRIII inhibited invasion, whereas TβRIII-cyto did not (Figure 3B). Consistent with the TGF-β signaling data, TβRIII-T841A also inhibited invasion (Figure 3B), whereas TβRIII-del was completely unable to inhibit invasion (Figure 3B). The tight correlation between the ability of TβRIII mutants to inhibit TGF-β signaling (Figure 3A, supplementary Figure 5B is available at Carcinogenesis Online) and inhibit breast cancer invasion (Figure 3B) supports a functional relationship between these effects. This functional relationship is further supported by the ability of pharmacological inhibition of ALK5 to inhibit invasion in the context of TβRIII-del expression (Figure 3C).

Fig. 3.

The interaction of TβRIII with GIPC is required for TβRIII-mediated suppression of TGF-β signaling and invasion. (A) 4T1 cells were infected with adenoviral constructs of green fluorescent protein (GFP), TβRIII, TβRIII-cyto, a mutant unable to bind β-arrestin2 (TβRIII-T841A) or a mutant unable to bind GIPC (TβRIII-del) for 48 h. Cells were then plated and serum starved for 4 h, stimulated with the indicated doses of TGF-β for 20 min and subjected to western blot analysis with the indicated antibodies. (B) 4T1 cells were infected with adenoviral constructs of GFP, TβRIII, TβRIII-cyto, TβRIII-T841A or TβRIII-del for 48 h, plated on Matrigel transwells and allowed to invade for 24 h. Counts of three random fields were averaged and representative data of three independent experiments are shown. (C) 4T1 cells were infected with GFP, TβRIII or TβRIII-del constructs for 48 h, preincubated with either vehicle [dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)] or the ALK5 inhibitor SB431542 (20 μM) for 20 min prior to plating on Matrigel transwells and allowed to invade for 24 h. Counts of three random fields were averaged and representative data of three independent experiments are shown. (D) 4T1 cells stably transfected with TβRIII or empty vector (Neo) were cotransfected with either GFP or shGIPC plasmid for 48 h. Cells were then serum starved for 4 h, stimulated with the indicated doses of TGF-β for 20 min and subjected to western blot analysis with the indicated antibodies. (E) 4T1 cells stably transfected with TβRIII or empty vector (Neo) were cotransfected with either GFP vector or shGIPC plasmid for 48 h. Cells were then plated on Matrigel transwells and allowed to invade for 24 h. Counts of three random fields were averaged and representative data of three independent experiments are shown; *P < 0.05.

While deletion of the C-terminal three amino acids in TβRIII-del is known to abrogate the interaction of TβRIII with GIPC (18), this region could also mediate other TβRIII functions. To investigate the specific function of GIPC, we utilized short hairpin RNA-mediated silencing of GIPC expression, which efficiently decreased GIPC expression (Figure 3D). Consistent with a role for GIPC in TβRIII-mediated inhibition of TGF-β signaling and breast cancer invasion, short hairpin RNA-mediated silencing of GIPC expression attenuated both TβRIII-mediated inhibition of TGF-β signaling (Figure 3D, supplementary Figure 5C is available at Carcinogenesis Online) and TβRIII-mediated inhibition of invasion (Figure 3E). Taken together, these data support a model in which TβRIII through interacting with GIPC inhibits TGF-β signaling to inhibit breast cancer invasion.

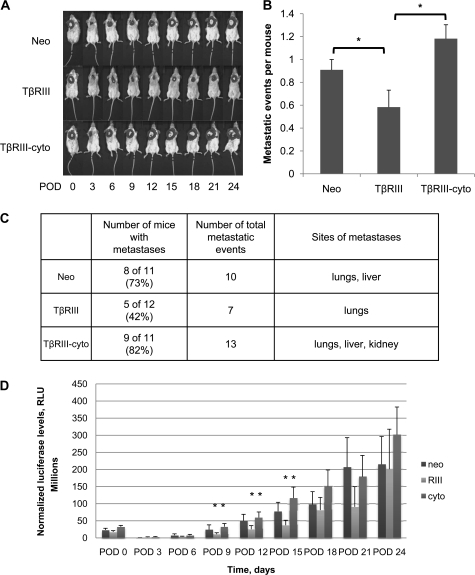

The cytoplasmic domain of TβRIII has a role in TβRIII-mediated suppression of breast cancer progression

Having established that the cytoplasmic domain of TβRIII has an important role in TβRIII-mediated inhibition of migration and invasion, coupled with our previous findings that TβRIII suppresses breast cancer metastases in vivo, we examined the role of the cytoplasmic domain of TβRIII in TβRIII-mediated suppression of breast cancer progression in vivo in the 4T1 syngeneic murine model of breast cancer. The 4T1 cells were stably cotransfected with a constitutively active luciferase reporter, which allowed the non-invasive in vivo tracking of cells during tumor development, along with either Neo, TβRIII or TβRIII-cyto. After cells were injected, primary tumors were allowed to develop for 12 days, after which they were surgically excised and assessed. After excision of the primary tumor, the formation of metastases was followed by bioluminescent imaging every 3 days over a period of 24 days. Consistent with our previous studies (11), there were no significant differences in primary tumor growth among the 4T1-Neo, 4T1-TβRIII or 4T1-TβRIII-cyto groups, as measured by both primary tumor mass and volume (supplementary Figure 3 is available at Carcinogenesis Online). However, consistent with our previous studies (11), mice with the 4T1-TβRIII cells had a delay tumor metastasis onset and decreased metastatic tumor burden as compared with mice injected with the control 4T1-Neo cells (Figure 4A and D). In contrast to the results with mice with the 4T1-TβRIII cells, mice with the 4T1-TβRIII-cyto cells had no delay in onset of tumor metastases and no decrease in metastatic tumor burden as compared with mice with the control 4T1-Neo cells (Figure 4A and D). Upon necropsy, the 4T1-Neo, 4T1-TβRIII and 4T1-TβRIII-cyto mice were examined for gross metastatic lesions. Consistent with bioluminescent imaging, significantly more lesions were found in the mice with 4T1-Neo cells and 4T1-TβRIII-cyto as compared with mice with 4T1-TβRIII cells (Figure 4B and C).

Fig. 4.

The cytoplasmic domain of TβRIII has a role in TβRIII-mediated suppression of breast cancer progression. 4T1 cells stably transfected with TβRIII, TβRIII-cyto or empty vector (Neo) were injected into the axillary mammary fat pad of groups of 15 Balb/c mice, with excision of the primary tumors after 12 days. (A) Bioluminescence imaging was conducted every 3 postoperative days (POD) and representative images are shown. (B) Number of metastatic event per mouse. The number of grossly observed metastatic lesions upon necropsy in each group of mice is presented. (C) Table enumerating the metastatic number, incidence and sites in each group of mice. (D) Bioluminescent intensities of tumors. Mean signal intensities for each group of mice are plotted; *P < 0.05.

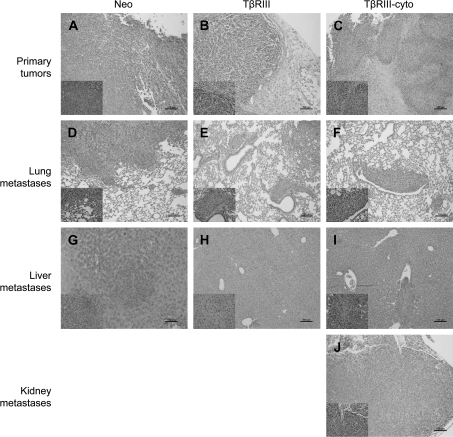

Further histological examination of the primary tumors demonstrated local invasiveness of the primary tumor into the stroma in the 4T1-Neo (Figure 5A) and 4T1-TβRIII-cyto (Figure 5C) tumors, whereas the 4T1-TβRIII tumors instead displayed a well-demarcated border with the surrounding stroma (Figure 5B). Furthermore, lung metastases from 4T1-Neo (Figure 5D) and 4T1-TβRIII-cyto (Figure 5F) tumors revealed invasion into the lung parenchyma, whereas lung metastases from 4T1-TβRIII tumors (Figure 5E) were smaller and well circumscribed. In addition, while 4T1-Neo and 4T1-TβRIII-cyto tumors both metastasized to the liver (Figure 5G and I), and a 4T1-TβRIII-cyto tumor metastasized to the kidney (Figure 5J), none of the 4T1-TβRIII tumors metastasized to these sites (Figure 5H). These studies support a specific suppressor effect of TβRIII on breast cancer invasiveness and metastasis mediated through its cytoplasmic domain.

Fig. 5.

The cytoplasmic domain of TβRIII has a role in TβRIII-mediated suppression of breast cancer invasiveness in vivo. Representative hematoxylin and eosin stains (at 10×) of primary tumors (A–C) demonstrate local invasion of tumor cells into the surrounding stroma in Neo and TβRIII-cyto mice (A and C), whereas the TβRIII tumors exhibit a clearly demarcated tumor border (B). Lung metastases (D–F) with a more invasive phenotype in the Neo and TβRIII-cyto groups (D and F); note that the TβRIII-cyto tumor impinges upon the airway (F), whereas the tumor adjacent to the airway in the TβRIII tumor retains its architecture (E). Liver metastases were also noted in the Neo and TβRIII-cyto groups (G and I), whereas none of the TβRIII liver tissues examined revealed metastatic lesions (H). A metastatic tumor in the kidney was noted in one of the TβRIII-cyto mice (J); Scale bar = 100 μm.

To investigate the mechanism of the cytoplasmic domain of TβRIII on decreasing metastasis in vivo, we performed immunohistochemistry for proliferating cell nuclear antigen as a marker of proliferation in the primary tumor and lung metastases. There were no significant differences in proliferating cell nuclear antigen staining between 4T1-Neo, 4T1-TβRIII and 4T1-TβRIII-cyto tumors in either the primary or metastatic lesions (supplementary Figure 4A and B is available at Carcinogenesis Online). We also performed terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated deoxyuridine triphosphate nick end labeling staining as a marker of apoptosis in the primary tumor and lung metastases. Similarly, there were no significant differences observed between 4T1-Neo, 4T1-TβRIII and 4T1-TβRIII-cyto tumors for terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated deoxyuridine triphosphate nick end labeling staining (supplementary Figure 4C and D is available at Carcinogenesis Online). These results suggested that differences in proliferation or apoptosis do not account for the differences in invasion and metastases among 4T1-Neo, 4T1-TβRIII and 4T1-TβRIII-cyto tumors.

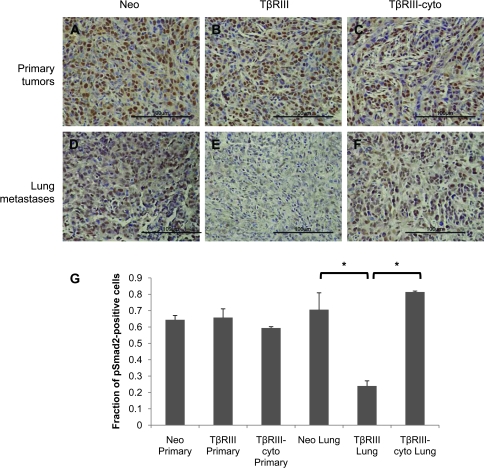

As we had observed differences in TGF-β signaling between 4T1-Neo, 4T1-TβRIII and 4T1-TβRIII-cyto that potentially accounted for differences in cell migration and invasion in vitro, we explored whether differences in TGF-β signaling could account for differences in cancer progression in vivo. Tissues from 4T1-Neo, 4T1-TβRIII and 4T1-TβRIII-cyto tumors and their lung metastases were analyzed for phospho-Smad2 staining. Although there was no difference in phospho-Smad2 staining in the 4T1-Neo, 4T1-TβRIII and 4T1-TβRIII-cyto primary tumors (Figure 6A–C), we did observe a dramatic decrease in phospho-Smad2 staining in pulmonary metastases from 4T1-TβRIII tumors relative to pulmonary metastases from 4T1-TβRIII-cyto and 4T1-Neo tumors (Figure 6D–G). These results suggest that TβRIII specifically suppresses TGF-β signaling in the metastatic tumor microenvironment specifically through functions mediated through its cytoplasmic domain.

Fig. 6.

The cytoplasmic domain of TβRIII has a role in TβRIII-mediated inhibition of TGF-β signaling in vivo. (A–F) Tissues sections of primary tumors and lung metastasis from mice implanted with 4T1-Neo, 4T1-TβRIII and 4T1-TβRIII-cyto cells were stained with phospho-Smad2 antibody. Representative results are shown (at 40×). Scale bar = 100 μm. (G) Quantification of pSmad2-positive cells. Three random fields were counted for pSmad2-positive cells and total number of cells and averaged; *P < 0.05.

Discussion

Breast cancer remains a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, with most of this morbidity and mortality resulting from recurrent and metastatic disease (27). Previous studies have amply demonstrated an important role for TGF-β signaling during mammary carcinogenesis. In early breast cancer progression, TGF-β generally acts as a tumor suppressor, inhibiting proliferation and promoting apoptosis. However, breast cancer cells in an established tumor become resistant to TGF-β-mediated effects on proliferation and apoptosis through an incompletely understood process and instead respond with increased migration and invasion. We have previously reported that the TGF-β superfamily co-receptor TβRIII is a suppressor of breast cancer progression, with frequent loss during breast cancer progression corresponding with decreased patient survival (11). Functionally, TβRIII inhibited tumor invasiveness in vitro and tumor invasion, angiogenesis and metastasis in vivo (11). Mechanistically, TβRIII appeared to function, at least in part, by undergoing ectodomain shedding, with the resulting sTβRIII antagonizing TGF-β signaling to reduce invasiveness and angiogenesis in vivo (11). In the present study, we further investigate the mechanism by which TβRIII mediates its suppressor of cancer progression function. We demonstrate that the cytoplasmic domain of TβRIII has an important role in TβRIII-mediated suppression of cancer progression, as deletion of the cytoplasmic domain abolishes the ability of TβRIII to inhibit migration or invasion in vitro and invasion and cancer progression in vivo. Mechanistically, TβRIII-mediated inhibition of migration and invasion appears to be modulated by TβRIII-mediated inhibition of TGF-β signaling, as supported by (i) the tight correlation between the ability of TβRIII mutants to inhibit TGF-β signaling and to inhibit migration and invasion in vitro; (ii) the tight correlation between diminished TGF-β signaling and decreased invasion and metastasis mediated by TβRIII in vivo; (iii) the ability of directly inhibiting TGF-β signaling to mimic the effects of TβRIII on inhibiting migration in vitro and (iv) the ability of bypassing TβRIII-mediated inhibition of TGF-β signaling to abrogate TβRIII-mediated inhibition of migration and invasion in vitro. Finally, we demonstrate that a discrete function of the cytoplasmic domain of TβRIII, namely binding to the PDZ domain-containing protein, GIPC, is largely responsible for mediating the effects of TβRIII on inhibiting TGF-β signaling and inhibiting cell migration and invasion in vitro, as either inhibiting the ability of TβRIII to bind GIPC or silencing GIPC expression is sufficient to abolish these effects. These results provide another mechanism by which TβRIII mediates its suppressor of cancer progression effects and emphasize the importance of the conserved TβRIII cytoplasmic domain in mediating TβRIII functions.

How does TβRIII inhibit TGF-β signaling through its cytoplasmic domain and GIPC-binding function? While we have previously demonstrated that TβRIII can inhibit TGF-β signaling through generation of sTβRIII, which sequesters TGF-β to inhibit TGF-β signaling (11), here we demonstrate that TβRIII and TβRIII-cyto do not differ in their ability to produce or to inhibit cell migration through sTβRIII. Thus, differences in generation of sTβRIII probably do not account for cytoplasmic domain-mediated inhibition of TGF-β signaling. We have also previously demonstrated that GIPC binding to TβRIII stabilized TβRIII on the cell surface and increased TGF-β signaling in epithelial cells and myoblasts (18). However, these studies utilized GIPC overexpression as opposed to the loss of function studies performed here. In addition, breast epithelial and/or breast cancer cells could have altered responsiveness to GIPC relative to the mink lung epithelial and rat myoblasts used in our prior studies (18). Indeed, TβRIII has already been demonstrated to have context-dependent effects on TGF-β signaling, also inhibiting TGF-β signaling in LLC-PK1 porcine epithelial cells (28). Furthermore, in the prior studies, we focused on TGF-β-mediated inhibition of proliferation and TGF-β-stimulated gene expression, without examining direct effects on Smad phosphorylation (18), whereas here, we focused on TGF-β-mediated Smad phosphorylation and effects on migration and invasion. In any case, the ability of GIPC to regulate to cell surface stability of TβRIII suggests that GIPC might serve to regulate TGF-β signaling by regulating its internalization and trafficking. Consistent with this hypothesis, the other scaffolding protein that interacts with the cytoplasmic domain of TβRIII, β-arrestin2, functions to regulate TβRIII endocytosis and TGF-β signaling (17). In addition, we have demonstrated that internalization of TβRIII through both clathrin-dependent and clathrin-independent signaling pathways is important for TβRIII-mediated signaling through both Smad-dependent and Smad-independent signaling pathways (23). Alternatively, GIPC could be functioning as a scaffolding protein to link TβRIII to other pathways that either directly or indirectly inhibits TGF-β signaling. As we have demonstrated that the interaction of GIPC with TβRIII can have context-dependent effects on TGF-β signaling, current studies are aimed at defining the precise mechanism by which TβRIII and GIPC function to regulate TGF-β signaling, including the connection between receptor trafficking and signaling.

Here, we present data supporting a model for TβRIII in inhibiting breast cancer progression through inhibition of TGF-β signaling, not through generation of sTβRIII but through its cytoplasmic domain. In separate studies, we have also demonstrated that TβRIII might inhibit breast cancer progression through TGF-β signaling-independent and β-arrestin2-dependent activation of Cdc42 to inhibit breast cancer cell migration (16) as well as through β-arrestin2-dependent inhibition of nuclear factor-kappaB signaling to inhibit breast cancer cell migration (24). Taken together, these results suggest several mechanisms that could either act in concert or in isolation to mediate the suppressor of cancer progression function of TβRIII. These multiple mechanisms by which TβRIII functions also provide an explanation for the selective pressure which probably results in the frequent loss of TβRIII expression during breast cancer progression, as we have already reported (11). While these mechanisms may function in isolation, as TβRIII-cyto also produces sTβRIII (supplementary Figure 1A is available at Carcinogenesis Online), why does it not have any effect in inhibiting cell migration and invasion in vitro and cancer progression in vivo? While this paradox remains to be fully explored, it is possible that the different mechanisms defined operate in different contexts or that TβRIII-cyto, which cannot be internalized and downregulated (23), functions as a constitutively active ligand presenter and functionally competes with sTβRIII as a suppressor of signaling. These possibilities are currently being explored with extracellular domain mutants to further delineate the contribution of the cytoplasmic domain in TGF-β signaling and migration and invasion.

In summary, our work has demonstrated that the cytoplasmic domain of TβRIII is critical for its function in inhibiting migration and invasion, as well as TβRIII's role in attenuating TGF-β signaling. In vivo, the cytoplasmic domain is important for the ability of TβRIII to inhibit metastatic potential. Furthermore, we have identified the interaction with GIPC as a critical mediator of TβRIII's effects in vitro on signaling and invasion. Coupled with further work to identify the contribution of GIPC–TβRIII interactions in vivo, these studies have the potential to open a path toward a novel target for the treatment of breast cancer patients.

Supplementary material

Supplementary Figures 1–5 can be found at http://carcin.oxfordjournals.org/

Funding

Department of Defense Breast Cancer Research Program Predoctoral Fellowship (to J.D.L.); National Institute of Health/National Cancer Institute (R01-CA106307, R01-CA135006) to G.C.B.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Mark Dewhirst (Duke University) for generously providing the 4T1 cells stably transfected with the luciferase gene and Dr Jeff Rathmell (Duke University) for generously providing the shGIPC plasmid.

Conflict of Interest Statement: None declared.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- DMEM

Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium

- GIPC

GAIP-interacting protein C-terminus

- sTβRIII

soluble TβRIII

- TGF-β

transforming growth factor-β

- TβRI

type I transforming growth factor-β receptor

- TβRII

type II transforming growth factor-β receptor

- TβRIII

type III transforming growth factor-β receptor

References

- 1.Blobe GC, et al. Role of transforming growth factor {beta} in human disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2000;342:1350–1358. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005043421807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gordon KJ, et al. Role of transforming growth factor-beta superfamily signaling pathways in human disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2008;1782:197–228. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Massague J. TGF-beta signal transduction. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1998;67:753–791. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pierce DF, Jr, et al. Inhibition of mammary duct development but not alveolar outgrowth during pregnancy in transgenic mice expressing active TGF-beta 1. Genes Dev. 1993;7:2308–2317. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.12a.2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pierce DF, Jr, et al. Mammary tumor suppression by transforming growth factor beta 1 transgene expression. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:4254–4258. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.10.4254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bottinger EP, et al. Transgenic mice overexpressing a dominant-negative mutant type II transforming growth factor {beta} receptor show enhanced tumorigenesis in the mammary gland and lung in response to the carcinogen 7,12-dimethylbenz-[a]-anthracene. Cancer Res. 1997;57:5564–5570. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siegel PM, et al. Transforming growth factor beta signaling impairs Neu-induced mammary tumorigenesis while promoting pulmonary metastasis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:8430–8435. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0932636100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gobbi H, et al. Loss of expression of transforming growth factor beta type II receptor correlates with high tumour grade in human breast in-situ and invasive carcinomas. Histopathology. 2000;36:168–177. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2000.00841.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gobbi H, et al. Transforming growth factor-{beta} and breast cancer risk in women with mammary epithelial hyperplasia. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:2096–2101. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.24.2096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ghellal A, et al. Prognostic significance of TGF beta 1 and TGF beta 3 in human breast carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2000;20:4413–4418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dong M, et al. The type III TGF-beta receptor suppresses breast cancer progression. J. Clin. Invest. 2007;117:206–217. doi: 10.1172/JCI29293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Finger EC, et al. TbetaRIII suppresses non-small cell lung cancer invasiveness and tumorigenicity. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29:528–535. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hempel N, et al. Loss of betaglycan expression in ovarian cancer: role in motility and invasion. Cancer Res. 2007;67:5231–5238. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gordon KJ, et al. Loss of type III transforming growth factor {beta} receptor expression increases motility and invasiveness associated with epithelial to mesenchymal transition during pancreatic cancer progression. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29:252–262. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Turley RS, et al. The type III transforming growth factor-beta receptor as a novel tumor suppressor gene in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2007;67:1090–1098. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mythreye K, et al. The type III TGF-beta receptor regulates epithelial and cancer cell migration through beta-arrestin2-mediated activation of Cdc42. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:8221–8226. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812879106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen W, et al. Beta-arrestin 2 mediates endocytosis of type III TGF-beta receptor and down-regulation of its signaling. Science. 2003;301:1394–1397. doi: 10.1126/science.1083195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blobe GC, et al. A novel mechanism for regulating transforming growth factor beta (TGF-beta) signaling. Functional modulation of type III TGF-beta receptor expression through interaction with the PDZ domain protein, GIPC. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:39608–39617. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106831200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blobe GC, et al. Functional roles for the cytoplasmic domain of the type III transforming growth factor beta receptor in regulating transforming growth factor beta signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:24627–24637. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100188200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Santander C, et al. Betaglycan induces TGF-beta signaling in a ligand-independent manner, through activation of the p38 pathway. Cell. Signal. 2006;18:1482–1491. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2005.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.You HJ, et al. The type III TGF-beta receptor signals through both Smad3 and the p38 MAP kinase pathways to contribute to inhibition of cell proliferation. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28:2491–2500. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wieman HL, et al. An essential role for the Glut1 PDZ-binding motif in growth factor regulation of Glut1 degradation and trafficking. Biochem. J. 2009;418:345–367. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Finger EC, et al. Endocytosis of the type III transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-beta) receptor through the clathrin-independent/lipid raft pathway regulates TGF-beta signaling and receptor down-regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:34808–34818. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804741200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.You HJ, et al. The type III transforming growth factor-{beta} receptor negatively regulates nuclear factor-{kappa}B signaling through its interaction with {beta}-arrestin2. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30:1281–1287. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Criswell TL, et al. Modulation of NFkappaB activity and E-cadherin by the type III transforming growth factor beta receptor regulates cell growth and motility. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:32491–32500. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704434200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bandyopadhyay A, et al. Antitumor activity of a recombinant soluble betaglycan in human breast cancer xenograft. Cancer Res. 2002;62:4690–4695. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kamangar F, et al. Patterns of cancer incidence, mortality, and prevalence across five continents: defining priorities to reduce cancer disparities in different geographic regions of the world. J. Clin. Oncol. 2006;24:2137–2150. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eickelberg O, et al. Betaglycan inhibits TGF-beta signaling by preventing type I-type II receptor complex formation. Glycosaminoglycan modifications alter betaglycan function. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:823–829. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105110200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.