Abstract

Studies suggest that deficits in social problem-solving may be associated with increased risk of depression and suicidality in children and adolescents. It is unclear, however, which specific dimensions of social problem-solving are related to depression and suicidality among youth. Moreover, rational problem-solving strategies and problem-solving motivation may moderate or predict change in depression and suicidality among children and adolescents receiving treatment. The effect of social problem-solving on acute treatment outcomes were explored in a randomized controlled trial of 439 clinically depressed adolescents enrolled in the Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS). Measures included the Children's Depression Rating Scale-Revised (CDRS-R), the Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire – Grades 7-9 (SIQ-Jr), and the Social Problem Solving Inventory-Revised (SPSI-R). A random coefficients regression model was conducted to examine main and interaction effects of treatment and SPSI-R subscale scores on outcomes during the 12-week acute treatment stage. Negative problem orientation, positive problem orientation, and avoidant problem-solving style were non-specific predictors of depression severity. In terms of suicidality, avoidant problem-solving style and impulsiveness/carelessness style were predictors, whereas negative problem orientation and positive problem orientation were moderators of treatment outcome. Implications of these findings, limitations, and directions for future research are discussed.

Keywords: adolescent, depression, problem solving, treatment

Deficits in problem-solving have been associated with depression (Haaga, Fine, Terrill, Stewart, & Beck, 1993) and suicidality (Dixon, Heppner, & Rudd, 1994) among adults. Moreover, research suggests a cognitive orientation toward problems is predictive of depression in adults (Haaga, Fine, Terrill, Stewart, & Beck, 1995; D'Zurilla & Sheedy, 1991; Heppner, Kampa, & Brunning, 1987). Research with children and adolescents is comparable and indicates that deficits in social problem-solving may be associated with increased risk for depression and suicidality (Asarnow, Carlson, & Guthrie, 1987; Fremouw, Callahan, & Kashden, 1993; Rotheram-Borus, Trautman, Dopkins, & Shrout, 1990; Spirito, Overholser, & Stark, 1989; Speckens & Hawton, 2005). While it is clear that problem-solving deficits are related to risk for depression and suicide in both adults and youth, the nature of these deficits and how they specifically account for increased risk is not yet understood; a number of questions remain to be addressed.

It is unclear the extent to which different aspects of social problem-solving contribute to depression and suicide among youth. Social problem-solving has been conceptualized as composed of two processes: problem orientation and rational problem-solving skills (D'Zurilla, 1986). Problem-solving orientation includes the person's awareness of problems, personal assessment of his or her ability to solve the problems, and expectations about the effectiveness of problem-solving attempts. Rational problem-solving, in contrast, is a person's ability to logically identify problems, define them, generate solutions, execute those solutions, and monitor solution effectiveness (Reinecke, DuBois, & Schultz, 2001). Effective social problem-solving can increase situational coping and behavioral competence, which in turn may prevent or reduce emotional distress (D'Zurilla & Nezu, 1999). It follows that social problem-solving should be associated with severity of depression and suicidality (Nezu & D'Zurilla, 1989; Speckens & Hawton, 2005). Available research indicates that both rational problem-solving and problem-solving motivation may be relevant for understanding depression and suicide.

A negative problem solving orientation includes cognitions and emotions that are hypothesized to inhibit adaptive problem-solving. Studies suggest associations may exist between negative problem-solving orientation and depression, hopelessness, and suicidal ideation among adults (D'Zurilla, Chang, Nottingham, & Faccini, 1998) and adolescents (D'Zurilla et al., 1998). Thus, an inability to maintain a positive problem-solving orientation may also be a salient factor in the etiology of depression and suicidality. For example, levels of depression among college students have been found to be significantly related to problem-solving orientation, but not problem-solving per se (Haaga et al., 1995). A similar pattern of results has been found in research with depressed youth as adolescent suicide attempters have been found to display significant deficits in both problem orientation and problem-solving skills when compared to normal controls (Sadowski & Kelly, 1993). Results indicate that for adolescents both components of social problem-solving may be salient. Reinecke, DuBois, and Schultz (2001) found negative problem-solving orientation and avoidant or impulsive problem-solving style to be associated with depression severity among inpatient adolescents. The same study found that rational problem-solving was not significantly correlated with severity of depression or hopelessness. In fact, other work (Rotherham-Borus et al., 1990) suggests that individuals with a history of suicidality generated significantly fewer alternative solutions in problem-solving, even after controlling for depression and other cognitive variables (such as IQ and coping style). Taken together, this work suggests that one's orientation toward one's problems, as opposed to one's ability to rationally derive solutions, may be more important in understanding the etiology of depression.

A second issue requiring investigation is the manner in which social problem solving deficits are related to treatment and treatment outcomes. Several studies have examined social problem-solving as a predictor or moderator of treatment outcome in adults. Joiner and colleagues (2001), for example, found that positive problem-solving attitudes predicted enhanced treatment response. Similarly, Chang (2002) found that social problem-solving contributed to the prediction of severity of depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation beyond what was accounted for by perfectionism. Moreover, in two studies by Nezu & Ronan (1985; 1988), problem-solving appraisal predicted and moderated change in depression severity. More specifically, results indicated that effective problem-solvers, under high-stress, reported lower levels of depression than ineffective problem-solvers. Problem-solving was found to have a significant direct effect on depression severity, as well as mediate the effect of negative life events on depression. In a similar manner, Garland, Harrington, House, and Scott (2000) found, in a study of adults with Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) treated with medication, baseline deficits in problem-solving skills predicted outcome at 3 and 6 month. We are unaware of research examining problem-solving's utility as a predictor or moderator of treatment outcome among adolescents.

There are two major treatment models that make differential predictions about groups most likely to benefit from treatment: A compensation model, which focuses on remediation of weaknesses, and predicts that individuals with the greatest skills deficits will show the largest therapeutic improvement; and a capitalization model that assumes therapy draws on a patient's strengths and predicts that individuals with the least amount of skills deficits will show the greatest improvement (Snow, 1991). Although the focus of CBT is often on building strengths and correcting thought distortions (thus seemingly most compatible with a compensation model), treatment outcome studies of CBT for depression often suggest more of a capitalization effect (Rude & Rehm, 1991). The literature suggests that depressed patients with fewer cognitive deficits have more favorable outcomes than do those with more cognitive deficits when treated with CBT (Rude and Rehm, 1991; Hamilton & Dobson, 2002; Simons, Gordon, Monroe, & Thase, 1995). Sotsky et al. (1991) found that low levels of cognitive distortions predicted greater treatment response (compared with placebo) only for patients who received CBT, not IPT, suggesting low levels of dysfunctional attitudes may be beneficial only for treatment with CBT. Following this research, we predicted a significant interaction between type of treatment and pretreatment level of social problem-solving motivation, such that those with higher motivation for problem-solving would benefit most from treatment with a CBT component.

Inconsistencies in the literature surrounding relations between problem-solving, mood, and suicide stem, at least in part, from differences in measures of problem-solving abilities. D'Zurilla and Maydeu-Olivares (1995) have distinguished between two kinds of problem-solving measures—process measures and outcome measures. Process measures assess the attitudes and skills involved in finding effective solutions to specific problems; whereas outcome measures assess the quality of specific solutions. Thus, an outcome measure may not provide specific information about the nature of process abilities or deficits. D'Zurilla and Nezu (1990) have distinguished between two types of process measures, those tapping problem orientation and those assessing problem-solving skills. As these process measures are only moderately correlated (D'Zurilla & Nezu, 1990), it is important to include both in social problem-solving research. The Social Problem-Solving Inventory—Revised (SPSI-R; D'Zurilla, Nezu, & Maydeu-Olivares, 1996) is a comprehensive, theoretically based process measure, and assesses five separate problem-solving factors. The positive problem orientation scale (PPO) taps constructive problem-solving cognition (e.g. optimism, commitment), whereas the negative problem orientation scale (NPO) taps inhibitive problem-solving cognitions (e.g. pessimism, self-blame). The rational problem solving scale (RPS) captures constructive problem-solving strategies (e.g. problem definition, generating solutions). The impulsive/carelessness style scale (ICS) reflects a maladaptive problem-solving pattern characterized as narrow and hurried. The avoidant style scale (AS) measures another maladaptive problem-solving pattern characterized by procrastination and passivity. Each component may have a unique relationship to risk for depression and suicide and to treatment response. By examining each of these problem-solving components independently it is possible to more fully understand specific relations between social problem-solving, depression, and suicide. The purpose of this study was to examine relations between rational problem-solving, problem-solving orientation, severity of depression, and suicidality among adolescents. A second goal was to determine if rational problem-solving or problem-solving orientation serve as moderators or predictors of depression and suicidality outcomes among depressed adolescents.

We hypothesized that problem-solving motivation (as measured by the negative problem orientation, positive problem orientation, inconsistent-careless style, avoidant style scales on the SPSI-R) would be associated with severity of depression and suicidality among youth at baseline. We also posited that problem-solving motivation would predict depression and suicidality outcomes across a 12-week treatment period. Further, we hypothesized that positive and negative problem-solving orientation would moderate acute treatment outcome, such that treatment that includes a CBT component would be more effective among those with higher levels of motivation for solving problems (i.e., lower scores on the negative problem-solving orientation subscale). In line with previous research, we did not expect to find a relation between rational problem-solving and depression and suicidality outcomes across a 12-week treatment period.

Methods

Study Participants

Participants were 439 clinically depressed adolescents enrolled in the Treatment for Adolescent Depression Study (TADS). Sponsored by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), the randomized controlled trial stage of TADS was designed to compare the effects of CBT (n=111), fluoxetine (FLX, n=109), their combination (COMB, n=107), and a pill placebo (PBO, n=112). For the FLX and PBO conditions, patients had one pharmacotherapist throughout the study who, in addition to monitoring clinical status and medication effects, offered general encouragement about the effectiveness of pharmacotherapy for MDD. TADS used a flexible dosing schedule that was dependent on pharmacotherapist-assigned CGI-Severity (CGI-S) score and the ascertainment of clinically significant adverse events. CBT in TADS began with a joint parent–adolescent rationale and goal setting session. It then included fourteen 60-minute sessions of either individual or family CBT over the first 12 weeks of treatment. The combination treatment condition (COMB) consisted of all the components from both the medication only and CBT-only arms, with the caveat that the teen, parent, and clinician were aware (for reasons of ecological validity) that the teen was receiving active medication (TADS, 2003). Randomized treatment was administered over a 12-week acute treatment period. All sites participating in TADS obtained Institutional Review Board approval.

Adolescents in the TADS sample were between 12 and 17 years of age (inclusive) with a current primary DSM-IV diagnosis of MDD. Fifty-four percent of the participants were girls, 74% were Caucasian, and the mean age was 14.6 (SD = 1.5) years. A score of 45 or greater on the Children's Depression Rating Scale – Revised (CDRS-R, Poznanski & Mokros, 1996) was required for study entry. The CDRS-R total scores at the pretreatment assessment ranged from 45 to 98 (mean = 60, SD = 10.4), indicative of mild to severe depression. This mean total CDRS-R score translates to a normed T score of 75.5 (SD = 6.43) suggesting moderate to severe depression. Details of consent and assent, rationale, methods, design of the study, and other demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample are detailed in previous reports (TADS Team, 2003; 2005).

Measures

Study assessments were conducted immediately prior to treatment (Baseline) and at two time points during the acute treatment period (Week 6 and Week 12). Clinical assessments were provided by an Independent Evaluator (IE) who was blind to treatment assignment. Self-report questionnaires completed by youth and parents were collected.

Children's Depression Rating Scale

Revised (CDRS-R, Poznanski & Mokros, 1996). The CDRS-R is a 17-item clinician-rated depression severity measure completed by the IE. Scores on the CDRS-R are based on interviews with the adolescent and parent and can range from 17 to 113, with higher scores representing more severe depression. The scale has good internal consistency (α = .85), inter-rater reliability (r = .92), test-retest reliability (r = .78), and is correlated with a range of validity indicators including global ratings and diagnoses of depression (Poznanski & Mokros, 1996).

Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire

Grades 7-9 (SIQ-Jr, Reynolds, 1987). The SIQ-Jr is a 15-item adolescent self-report measure of suicidal thinking with a possible range of scores between 0 and 90. Severity of suicidal ideation was based on the total score, with higher scores indicating more suicidality. The SIQ-Jr. has high internal consistency (coefficient alpha=.94) and moderate test-retest stability (r=.72).

The Social Problem-Solving Inventory

Revised (SPSI-R; D'Zurilla, Nezu, & Maydeu-Olivares, 1996) is a 52 item adolescent-report questionnaire, with five subscales that assess functional and dysfunctional cognitive and emotional orientations toward solving life problems. The subscales are labeled Positive Problem Orientation (PPO; 5 items, e.g., “Whenever I have a problem, I believe it can be solved.”), Negative Problem Orientation (NPO; 10 items, e.g., “When my first efforts to solve a problem fail, I get very frustrated.”), Rational Problem Solving (RPS; 20 items; e.g., “When I have a problem to solve, one of the things I do is analyze the situation and try to identify what obstacles are keeping me from getting what I want.”), Impulsivity-Carelessness Style (ICS; 10 items, e.g., “When I am attempting to solve a problem, I act on the first idea that occurs to me.”), and Avoidant Style (AS; 7 items, e.g., “I prefer to avoid thinking about the problems in my life instead of trying to solve them.”). The five subscales have good internal consistency and test-retest reliability (D'Zurilla, Nezu, & Maydeu-Olivares, 2003). Higher scores on the NPO, ICS, and AS reflect more a more maladaptive approach to problem-solving; whereas higher scores on the PPO and RPS indicate more adaptive problem-solving. The SPSI-R was originally developed for use with adults. Sadowski and colleagues (1994) explored the psychometric properties of the SPSI-R among adolescents between 13 and 17. Internal consistency estimates were adequate with coefficients between 0.85 and 0.90 for the total score and between 0.62 and 0.88 among the subscales.

Statistical Analyses

Primary outcomes were severity of depression and suicidality during the 12-week treatment period, as measured by independent clinician-report CDRS-R total score and the adolescent-report SIQ-Jr total score, respectively. An “intention-to-treat” (ITT) analysis approach was employed in which all 439 patients randomized to treatment were included in the analysis regardless of study completion, protocol adherence, or treatment compliance. Baseline sample median values were imputed for missing observations. At baseline 27 participants were missing a PPO score (median=8), 27 were missing a NPO score (median =20), 31 were missing a RPS score (median=31), 26 were missing an AS score (median =12), 31 were missing an ISC score (median=16), and 11 were missing a SIQ score (median =16). To assess possible bias due to data loss, groups with all data present (n=405) versus any data missing on the scales above (n=34) were compared on demographic variables and global depression severity using a general linear model analysis of variance with a posteriori t-tests for continuous variables and chi-square tests for dichotomous variables. No significant group differences were detected for age, CDRS-R depression severity, income, sex, or race (p > 0.05).

A general linear model analysis of variance (ANOVA), with a posteriori t-tests, was employed to compare the treatment arms on key baseline clinical characteristics. When the assumptions of this test were not met, a non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test was used. Chi-square tests were used for dichotomous variables. Pearson product-moment coefficients were calculated to examine the correlation between independent variables.

Non-directional hypotheses were tested and the level of significance was set at 0.05 for omnibus tests due to the exploratory nature of the analysis. A posteriori pair-wise comparisons were conducted at the 0.05 level of significance in the presence of a treatment or treatment-by-time effect.

Predictor/Moderator Analysis

Relations between social problem-solving scales and treatment outcomes were investigated using an analytic approach recommended by Kraemer and colleagues (Kraemer et al., 2002). By definition, a non-specific predictor is a pretreatment variable that has a significant effect on outcome regardless of treatment condition (i.e., main effect only). A moderator, on the other hand, is considered a special type of predictor whereby treatment effectiveness is significantly influenced by levels of the pretreatment factor and a significant interaction between the pretreatment factor and treatment (with or without a main effect of pretreatment factor) is demonstrated. Analyses yielding a significant variable-by-treatment interaction effect on outcome measure indicated the variable was a moderator. Analyses yielding a significant main effect of the variable on outcome but a non-significant variable-by-treatment interaction effect indicated that the variable was a non-specific predictor. The primary outcomes for all analyses were CDRS-R and SIQ-Jr scores.

The impact of treatment on the CDRS-R and SIQ-Jr outcome scores was modeled using a linear random coefficients regression model (RRM), which included the following terms used in the primary TADS analysis (TADS, 2004): fixed effects for treatment, time, treatment-by-time, site, as well as random effects for participant and participant-by-time. For each of the social problem-solving scales, the baseline score and its interaction terms (scale, scale-by-time, scale-by-treatment, and scale-by-treatment-by-time) were added to the above core analysis model to test whether any given social problem-solving subscale was a predictor or moderator of treatment outcome. In the event of a significant moderator (defined as scale-by-treatment-by-time effect, p≤.05), the scale was divided into low and high subgroups using the median slit method. The core primary analysis was then used to examine treatments effects within the low and high subgroups for the scale. Paired treatment contrasts were conducted only if there was a significant treatment or treatment-by-time effect within the subgroup.

Results

Baseline Analyses

Patients in the four randomized treatment conditions did not differ significantly at baseline with regard to CDRS-R depression severity, SIQ-Jr suicidality scores, SPSI subscales, age at time of consent, duration of the current depressive episode, or total number of concurrent psychiatric disorders (all tests, p>.05). Although differences in the SIQ-Jr total scores were not detected between the four treatment arms (Kruskal-Wallis, p=.572), the proportion of patients with a SIQ-Jr total score of 31 or greater was significantly higher in the COMB (39.3%) arm relative to FLX (25.7%, p=.036), CBT (24.3%, p=.025), and PBO (25.0%, p=.033). A score of 31 or above on this measure is indicative of clinically significant suicidal risk. Descriptive statistics for all variables at baseline are presented in Table I. As a group, participants demonstrated moderate-to-severe depression (CDRS, M=60.1, SD=10.39), and moderate-to-severe levels of suicidality (SIQ, M=23.7, SD=21.8).

Table 1.

Depression, suicidality, and social problem-solving: Means and standard deviations (SD)

| Total | COMB | FLX | CBT | PBO | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domain | Assessment | N | Mean ± SD |

N | Mean ± SD |

N | Mean ± SD | N | Mean ± SD |

N | Mean ± SD |

| Depression | CDRS-R total score | ||||||||||

| Baseline | 439 | 60.1+10.4 | 107 | 60.8±11.6 | 109 | 59.0±10.2 | 111 | 59.6±9.2 | 112 | 61.1±10.5 | |

| Week 6 | 389 | 42.1±12.3 | 98 | 38.5±12.7 | 99 | 39.4±11.5 | 97 | 45.3±11.8 | 95 | 45.4±11.6 | |

| Week 12 | 378 | 38.2±13.4 | 95 | 33.4±11.9 | 97 | 36.8±12.7 | 90 | 41.4±14.2 | 96 | 41.4±13.4 | |

| Suicidality | SIQ-Jr total score | ||||||||||

| Baseline | 439 | 23.5±21.6 | 107 | 27.2±24.5 | 109 | 21.8±19.1 | 111 | 21.8±21.0 | 112 | 23.4±21.3 | |

| Week 6 | 362 | 15.2±17.6 | 86 | 14.2±18.4 | 95 | 16.1±18.5 | 89 | 12.8±14.9 | 92 | 17.6±18.3 | |

| Week 12 | 370 | 13.4±16.5 | 90 | 12.5±16.5 | 97 | 14.8±17.3 | 91 | 11.9±14.9 | 92 | 14.4±17.3 | |

| Social Problem- Solving |

NPO subscale score--Baseline | 439 | 19.7±9.01 | 107 | 20.8±9.31 | 111 | 17.9±8.58 | 109 | 18.8±9.51 | 112 | 21.4±8.27 |

| PPO subscale score--Baseline | 439 | 7.81±3.71 | 107 | 7.54±4.14 | 111 | 8.40±3.33 | 109 | 7.68±3.54 | 112 | 7.63±3.77 | |

| RPS subscale score--Baseline | 439 | 29.5±14.8 | 107 | 28.4±16.4 | 111 | 32.3±14.5 | 109 | 28.8±14.2 | 112 | 28.35±13.9 | |

| ICS subscale score--Baseline | 439 | 15.8±7.76 | 107 | 15.9±8.41 | 111 | 15.0±7.43 | 109 | 14.8±7.88 | 112 | 17.5±7.09 | |

| AS subscale score--Baseline | 439 | 12.1±5.72 | 107 | 12.2±6.46 | 111 | 11.4±4.87 | 109 | 11.2±5.87 | 112 | 13.2±5.44 |

Note. CDRS-R=Children's Depression Rating Scale-Revised total score; SIQ-Jr=The Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire Grades 7-9 total score; PPO=Positive Problem Orientation Subscale; NPO=Negative Problem Orientation Subscale; RPS=Rational Problem Solving Subscale; ICS=Impulsivity/Carelessness Style Subscale; AS=Avoidance Style Subscale.

Correlation Analyses

At baseline, depression severity scores ranged from 45 to 98 and were significantly correlated with all predictor variables, with the exception of rational problem solving (r= −0.09) and impulsiveness/carelessness style (r= 0.10). Additionally, baseline depression and suicidality were moderately related (r=0.33, p<.001).

Correlation coefficients were conducted to examine multicollinearity among the predictor variables. As can be seen in Table II, significant associations were observed between many of the variables. Given the relatively large sample size, however, power for finding statistical significance was great. Despite the high correlations between several variables, statistical tests indicated that multicollinearity was not a significant problem. Variance inflation factors (VIF) were computed for each predictor variable to detect multicollinearity. As a rule of thumb, a VIF > 10 indicates problematic collinearity (Kennedy, 2003). The maximum VIF among our predictor variables was approximately 3, indicating that collinearity was not a significant issue.

Table 2.

Pearsons Product-Moment Correlation Matrix

|

Baseline Measures |

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. CDRS-R | ||||||

| 2. SIQTOT | 0.33** | |||||

| 3. NPO | 0.22** | 0.42** | ||||

| 4. PPO | −0.18** | −0.19** | −0.24** | |||

| 5. RPS | −0.09 | 0.03 | −0.007 | 0.71** | ||

| 6. ICS | 0.10* | 0.18** | 0.60** | −0.12* | −0.19** | |

| 7. AS | 0.19** | 0.27** | 0.74** | −0.25** | −0.084 | 0.65** |

CDRS-R= Children's Depression Rating Scale-Revised Total Score; SIQTOT= The Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire Total Score; PPO=Positive Problem Orientation; NPO=Negative Problem Orientation; RPS=Rational Problem Solving; ICS=Impulsivity/Carelessness Style; AS=Avoidance Style

p ≤ .05,

p ≤ .001

Predictor/Moderator Analysis for Depression Outcome

The results of these analyses are summarized in Table III. As indicated in Table III, three variables predicted treatment outcome in terms of severity of depression: NPO, PPO, and AS. None of the variables, however, moderated the effect of treatment.

Table III.

Predictors and Moderators of Acute Treatment Outcome (Depression)

| Scale | Scale F(df) | Scale × Treatment F(df) | Scale × Time F(df) | Scale × Treatment × Time F (df) | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NPO | 15.34 (1,428)** | 4.41 (3,735) | 4.41 (1,735)* | 0.46 (3,731) | Predictor |

| PPO | 9.62 (1,423)** | 0.83 (3,419) | 0.00 (1,727) | 0.51 (3,730) | Predictor |

| RPS | 2.37 (1,415) | 1.43 (3,414) | 0.00 (1,654) | 1.18 (3,653) | |

| AS | 8.75 (1,422)** | 0.27 (3,418) | 1.99 (1,739) | 1.54 (3,742) | Predictor |

| ICS | 2.61 (1,416) | 0.67 (3,412) | 3.28 (1,716) | 0.48 (3,716) | |

| Predictors and Moderators of Acute Treatment Outcome (Suicidality) | |||||

| Scale | Scale F(df) | Scale × Treatment F(df) | Scale × Time F(df) | Scale × Treatment × Time F (df) | Status |

| NPO | 80.91 (1,482)** | 1.15 (3,478) | 7.63 (1,527)** | 2.94 (3,524)* | Moderator |

| PPO | 7.04 (1,470)** | 2.99 (3,470)* | 0.96 (1,508) | 2.04 (3,508) | Moderator |

| RPS | 2.06 (1,484) | 0.29 (3,484) | 2.75 (1,473) | 0.41 (3,472) | |

| AS | 25.13 (1,470)** | 0.66 (3,469) | 2.13 (1,508) | 0.71 (3,507) | Predictor |

| ICS | 15.53 (1,417)** | 0.39 (3,469) | 0.00 (1,493) | 0.13 (3,492) | Predictor |

p ≤ .05,

p ≤ .01

Note: PPO=Positive Problem Orientation Subscale; NPO=Negative Problem Orientation Subscale; RPS=Rational Problem Solving Subscale; ICS=Impulsivity/Carelessness Style Subscale; AS=Avoidance Style Subscale

p ≤ .05,

p ≤ .01

Significant time (p<.001), negative problem orientation (p<.001), and NPO-by-time (p<.05) effects were demonstrated. All other terms were not significant. A main effect in absence of an interaction with treatment indicates that negative problem orientation is a predictor, but not a moderator, of outcome. More specifically, a more negative problem orientation at baseline predicted higher depression severity after 12 weeks of treatment, regardless of treatment condition.

Significant time (p<.001), treatment-by-time (p<.001), and positive problem orientation (p=.002) effects were demonstrated. All other terms were not significant. A main effect in absence of an interaction with treatment indicates that positive problem orientation is a predictor of outcome, but not a moderator of outcome. In this instance, a more positive problem orientation predicted improvement in depression severity regardless of treatment condition.

Significant time (p<.001) and avoidant style (p=.003) effects were demonstrated, while all other terms were not statistically significant. A main effect in absence of an interaction with treatment indicates that avoidant style is a predictor of outcome, but not a moderator of outcome. For all treatment conditions, higher avoidant style predicated less improvement in terms of depression severity at 12 weeks.

Significant effects for rational problem solving (p=.12) and impulsiveness/carelessness style (p=.11) were not found.

Predictor/Moderator Analysis for Suicidality Outcome

The results of these analyses are summarized in Table III. As indicated in Table III, two variables (AS and ICS) predicted treatment outcome in terms of suicidality, and NPO and PPO moderated the effect of treatment. Variables that moderated the effect of the assigned treatment were further analyzed based on dichotomous subgroups. A median split was performed on NPO, yielding subgroups with scores <20 (low negative problem solving orientation, n=217) and ≥20 (high negative problem solving orientation, n=222). A median split was also performed on PPO, yielding subgroups with scores <8 (low positive problem solving orientation, n=221) and ≥8 (high positive problem solving orientation, n=227). The week 12 CDRS-R least squares means and SDs for each moderator subgroup as well as results from a posteriori paired comparisons are shown in Table IV.

Table IV.

Moderators of Acute Treatment Outcome (Suicidality)

| Treatment Condition/Least Squares Mean (SEM) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moderator | Subgroups | No. | COMBO | FLX | CBT | PBO |

| NPO | 1. ≥ 20 | 222 | 23.6 (1.6)a | 21.0 (1.7)a | 20.2 (1.5)a | 20.3 (1.5)a |

| 2. < 20 | 217 | 13.3 (1.6)a | 15.3 (1.5)a | 11.1 (1.7)b | 16.8 (1.7)a | |

| PPO | 1. ≥ 8 | 227 | 15.0 (1.8)a | 17.2 (1.4)a | 13.3 (1.5)b | 15.3 (1.6)a |

| 2. < 8 | 221 | 21.2 (1.5)a | 18.8 (1.8)a | 19.1 (1.7)a | 22.2 (1.6)a | |

| Moderators of Acute Treatment Outcome (Suicidality) | ||||||

| Moderator | Subgroups | No. | Week 12 Mean (SEM) | Significant Differences | ||

| NPO | 1. ≥ 20 | 222 | 16.2 (18.8) | 1>2** | ||

| 2. < 20 | 217 | 10.5 (13.2) | ||||

| PPO | 1. ≥ 8 | 227 | 11.8 (16.2) | 2>1* | ||

| 2. < 8 | 221 | 15.2 (16.7) | ||||

Note: Means with the same superscript are not significantly different. PPO=Positive Problem Orientation Subscale; NPO=Negative Problem Orientation Subscale.

p ≤ .05,

p ≤ .01

Note: PPO=Positive Problem Orientation Subscale; NPO=Negative Problem Orientation Subscale.

p ≤ .05,

p ≤ .01

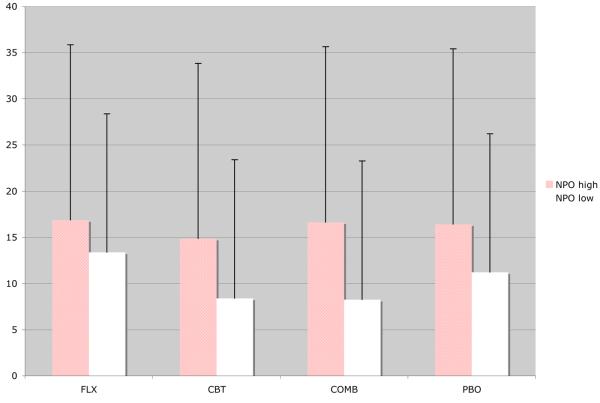

Main effects of negative problem orientation (p<.001), NPO-by-time (p=0.006), and NPO-by-treatment-by-time (p=0.032) were significant for the suicidality outcome. All other terms were not significant. A main effect along with an interaction with treatment indicates that negative problem orientation is a moderator of outcome. At high levels of negative problem orientation (≥20), all treatments were equally as effective at reducing suicidality. However, at low levels of negative problem orientation (< 20), CBT was more effective than the other treatments, which were not significantly different from each other. Figure 1 depicts these results.

Figure 1.

Mean SIQ scores at week 12

Note. SIQ scores are adjusted for the fixed (treatment, time, treatment-by-time, site) and random effects (patient, patient-by-time) included in the random coefficients regression model. High NPO was defined as a negative problem orientation scale score greater than or equal to 20 on the Social Problem-Solving Inventory – Revised.

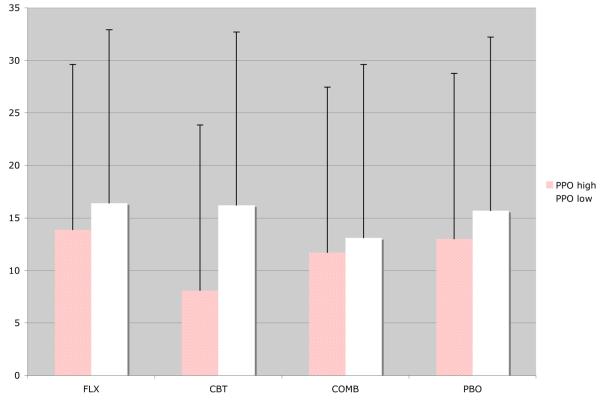

Significant effects for treatment (p<.01), time (p<.001), treatment-by-time (p<.05), positive problem orientation (p=.005), and PPO-by-treatment (p<.05) were demonstrated. All other terms were not statistically significant. A main effect and interaction effect with treatment indicates that positive problem solving is a moderator of outcome. Paired contrasts between treatment groups at week 12 indicated that at high levels of positive problem orientation (≥ 8), CBT was more effective than FLX, which did not differ significantly from the other treatments. At low levels of positive problem orientation (< 8), however, none of the treatments were significantly different from one another. Figure 2 depicts these results.

Figure 2.

Mean SIQ scores at week 12

Note. SIQ scores are adjusted for the fixed (treatment, time, treatment-by-time, site) and random effects (patient, patient-by-time) included in the random coefficients regression model. High PPO was defined as a positive problem orientation scale score greater than or equal to 8 on the Social Problem-Solving Inventory – Revised.

Significant time (p<.01) and avoidant style (p<.001) effects were demonstrated. All other terms, however, including the AS-by-treatment (p=.58) and AS-by-treatment-by-time (p=.54) interaction terms, were not statistically significant.

Significant time (p<.001) and impulsiveness/carelessness style (p<.001) effects were demonstrated. All other terms, however, including the ICS-by-treatment (p=.76) and ICS-by-treatment-by-time (p=.94) interaction terms, were not statistically significant. A main effect in absence of an interaction with treatment indicates that positive problem orientation is a predictor of outcome, but not a moderator of outcome.

No main effect was found for rational problem solving (p=.15), indicating it is neither a predictor nor moderator of suicidality.

In summary, scores on the SPSI-R pertaining to problem orientation (negative and positive) showed consistent associations with measures of depression severity and suicidality at baseline. Negative problem orientation and positive problem orientation were both predictors of depression severity and moderators of treatment outcome in terms of suicidality. Similarly, results indicated that problem-solving style, as opposed to orientation, is associated with depression severity and suicidal ideation, although associations were less noteworthy. It appears that an avoidant problem-solving style is a predictor for depression severity and suicidality; whereas, an impulsiveness/carelessness problem-solving style appeared to be a predictor for only suicidal ideation. By contrast, there was an absence of any significant associations involving rational problem-solving skills and either depression severity or suicidality.

Discussion

The present study sought to examine relations among social problem-solving, depression severity, and suicidality in a sample of clinically depressed adolescents. We found evidence to support our first hypothesis. Congruent with prior research (Reinecke, DuBois, & Schultz, 2001) results indicated no specific relationship between rational problem-solving and severity of depression at baseline. Significant associations between problem-solving motivation and severity of depression were found across the course of treatment. Problem solving motivation variables were also associated with level of suicidal ideation at baseline. In line with our second hypothesis, results indicated that depression and suicidality outcomes across a 12-week treatment period were related to problem orientation. Negative problem orientation was a predictor of depression severity and a moderator of suicidality. Analyses further suggested positive problem orientation to be a predictor of depression severity and moderator of suicidality, avoidant problem-solving style to be a predictor of both depression severity and suicidality, and impulsiveness/carelessness style to be a predictor of suicidality.

Although positive and negative problem orientations were non-specific predictors for the depression severity outcome, they moderated treatment outcome for suicidality. Moderation effects were such that treatment was more effective in reducing suicidality among those adolescents with high positive and low negative problem solving orientations. In line with our hypothesis, treatments with a cognitive-behavioral component were more effective for adolescents with higher levels of motivation for solving problems (i.e., lower scores on the negative problem-solving orientation subscale). Indeed, previous work has noted that a positive mood improves an individual's orientation toward problems (Joiner et al., 2001). These authors note that using pleasant activities to increase positive mood during treatment sessions, may facilitate problem solving treatment goals.

Findings of this study are consistent with prior research indicating a relationship between deficits in social problem-solving and risk for depression and suicide among college-age and adult populations (Zurilla et al., 1998; Dixon et al., 1994) and inpatient adolescents (Reinecke, DuBois, & Schultz, 2001). The present findings extend previous research by providing more specific information about the nature of the problem-solving deficits that may be linked with depression and suicidal risk in youth. Cumulatively, these findings suggest that the ability to maintain a positive problem orientation (or avoid a negative one), as well as having an adaptive approach to facing problems may play a role in risk for depression and suicide, and may be related to treatment outcome. Specific deficits in rational problem-solving abilities, on the other hand, may not be as salient, relative to other social problem-solving domains. Thus, results suggest that components of social problem-solving may be differentially important in regards to treating depression and suicide among adolescents. For example, a recent study documented that self-injurious adolescents did not show deficits in the quantity or quality of the solutions they generated to a challenging situation; however they selected more maladaptive responses from the range of possibilities and reported lower feelings of efficacy regarding their ability to implement adaptive solutions (Nock & Mendes, 2008).

Results of this study highlight the potential importance of problem orientation in depression and suicidality among youth. Perception of problem-solving ability and attitude towards solving problems appears more salient than self-reported ability to solve problems when it comes to depression and suicidality in depressed adolescents. Results also emphasize the importance of being cognizant of levels and dimensions of social problem-solving in treatment planning. Patients with low negative problem orientation and patients with high positive problem orientation appear to have better outcomes, in terms of suicidality. These patients have less doubt regarding their problem-solving ability, realistic perceptions of the threat of problems to their well-being, optimism about the outcome, and higher frustration tolerance (D'Zurilla, Nezu, & Maydeu-Olivares, 1996). CBT requires a great deal of “work” from the client (e.g. frequent sessions, homework, practicing new skills, challenging rigid beliefs), and research shows compliance with activities is an integral part of therapeutic success (Burns & Spangler, 2000; Rees, McEvoy & Nathan, 2005). However, adherence was not found to moderate or mediate the effect of treatment on depression in TADS (Silva et al., 2009). Nevertheless, adolescents with high negative problem orientation and low positive problem orientation may have more difficulty engaging in the demands of CBT (due to a belief that nothing will work, they are not capable of solving problems, etc.) and, therefore, may not experience as many gains from that particular treatment. On the other hand, adolescents with low negative problem orientation and high positive problem orientation may be more motivated to directly address their problems and to exert the effort required in CBT, thus making it a more effective treatment for this group.

Although rational problem-solving was not a predictor or moderator of treatment outcome in terms of depression severity or suicidality, these findings do not imply that rational problem-solving skills are unimportant for understanding and treating depressed and suicidal adolescents. It seems unlikely that specific competencies and skills in the domain of rational problem-solving have no relationship to depression and suicide among youth. Indeed, research has generally shown a link between behavioral problem-solving skills and psychopathology (Sadowski & Kelley, 1993). Inconsistencies may stem from methodological factors, differences in the severity of depression across studies, and developmental differences in how problem-solving skills are applied. It is also possible that there were pre-morbid deficits in rational problem-solving which contributed to the development of maladaptive problem orientation and problem-solving style. That is, a history of failed problem solving attempts due to deficits in rational problem-solving may lead to a negative problem orientation or maladaptive problem-solving style, which then is directly associated for risk of depression and suicide. Prospective studies and longitudinal research with at-risk samples would be useful in addressing these possibilities and speculations. It should also be noted that the rational problem-solving scale used in these analyses is a self-report measure. As such, it asks subjects to report on how they typically respond in problem-solving situations, their knowledge of and their perceived use of effective problem-solving skills. In real-life situations, however, individuals with poor problem orientation may not implement the best solutions or implement them incorrectly due to poor outcome expectancies, low frustration tolerance, emotional distress, or poor self-efficacy. Thus, despite their knowledge of effective problem-solving skills, in practice, they are poor rational problem-solvers. In response to this possibility, D'Zurilla and Maydeu-Olivares (1995) advocate the use of performance-based measures of social problem-solving ability in research, in addition to self-report inventories. Thus, follow-up studies assessing social problem-solving should include a measure, such as the problem-solving self-monitoring (PSSM) method (D'Zurilla & Nezu, 1999 & 2007), to assess problem-solving skills in the natural environment as well as solution implementation and problem-solving outcomes in specific situations.

Most prior research with adolescents has focused on more general indices of social problem-solving, without analyzing components (Sadowski & Kelley, 1993). These results highlight the importance of including both measures of problem orientation and problem-solving skills in future social problem-solving research. Previous studies have shown that measures are only moderately correlated (see D'Zurilla & Nezu, 1990), and the results in this study indicate that they also have unique associations with measures of mood and suicidality, as well as unique treatment implications.

These results are important from an applied standpoint in that current cognitive and behavioral approaches for treating depression and preventing suicide often focus on the development of rational problem-solving skills (Learner & Clum, 1990). Although acquisition of these skills may be beneficial, it appears that more attention should be directed towards alleviating a negative problem-orientation, creating a positive problem-orientation and targeting a patient's problem-solving style. These other components appear to be more salient in depression and suicide and may preclude or interfere with one's ability to effectively use rational problem-solving skills. It is possible that strategies such as motivational interviewing may increase the adolescent's ability to approach their problems in a positive manner. Therapists may also want to consider incorporating techniques from problem-solving therapy (PST; see D'Zurilla & Nezu, 1999 & 2007). PST has been found to be an effective treatment for depression (Bell & D'Zurilla, 2009) and focuses equally on problem orientation and problem-solving skills. Further, it emphasizes supervised practice of problem-solving skills in real-life situations in order to increase the effectiveness of actual problem-solving performance. By facilitating competent problem-solving performance and increasing self-efficacy, PST aims to strengthen positive problem orientation and reduce negative problem orientation (D'Zurilla & Nezu, 2007).

Several limitations of this research deserve note. First, although our findings are suggestive, we cannot infer causality. The identification of a predictor or moderator may lead to hypotheses about possible causal roles which can then be tested in future studies specifically designed for those purposes. Longitudinal studies of high-risk populations, in conjunction with ratings of mood and social problem-solving, should be prioritized in the future as a means of addressing these issues. Second, our findings may not generalize to youth with less severe depressive symptoms, or to youth seen in community settings. Deficits in social problem-solving may not be specific to clinical depression; rather it is possible they are affiliated with psychopathology in general. Associations between social problem-solving, mood, and suicidality may vary depending on specific diagnosis, gender, or developmental level and future research should examine social problem-solving among these different groups. Third, we included site as a covariate in the current analysis to be consistent with the statistical analysis approach applied in the TADS primary analysis (TADS Team, 2004). The TADS Team is preparing a manuscript detailing the influence of site on documented findings. A final concern is the reliance solely on a self-report measure of social problem-solving. The SPSI-R is a measure of the adolescent's perceived problem-solving abilities, rather than an objective gauge of problem-solving skill. Future research should include objective measures or tests of the patient's actual ability to solve actual real-life problems.

There are a number of conclusions we can draw from our results. First, clinicians would do well to assess multiple components of social problem-solving in the early stages of treatment planning; problem-solving orientation may indicate the likely effect of treatment, especially in regards to suicidality. Patients with higher positive problem orientation will likely benefit more from treatment than patients with low positive problem orientation. In parallel, patients with low negative problem orientation may show greater improvement. Second, certain aspects of social problem solving are more relevant to depression severity and suicidality than others. Problem-solving orientation and problem-solving style appear most important, while rational problem-solving abilities appear to be less so. Clinicians may want to focus on bolstering a positive attitude towards facing problems and reduce a negative orientation, rather than directly teaching problem solving skills. Third, evaluating the effects of factors such as life events and environmental influences will be important in understanding how the different components of social problem solving develop and relate to one another. Research identifying cognitive and social processes that maintain a certain problem-solving style may allow for the adaptation of CBT to systematically address these factors.

Acknowledgements

TADS is supported by contract N01 MH80008 from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) to Duke University Medical Center (John S. March, Principal Investigator). The Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS) was coordinated by the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences and the Duke Clinical Research Institute at Duke University Medical Center in collaboration with the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), Rockville, Maryland. The Coordinating Center principal collaborators are John March, Susan Silva, Stephen Petrycki, John Curry, Karen Wells, John Fairbank, Barbara Burns, Marisa Domino, and Steven McNulty. The NIMH principal collaborators are Benedetto Vitiello and Joanne Severe. Principal Investigators and Co-investigators from the clinical sites are as follows: Carolinas Medical Center: Charles Casat, Jeanette Kolker, Karyn Riedal, Marguerita Goldman; Case Western Reserve University: Norah Feeny, Robert Findling, Sheridan Stull, Felipe Amunategui; Children's Hospital of Philadelphia: Elizabeth Weller, Michele Robins, Ronald Weller, Naushad Jessani; Columbia University: Bruce Waslick, Michael Sweeney, Rachel Kandel, Dena Schoenholz; Johns Hopkins University: John Walkup, Golda Ginsburg, Elizabeth Kastelic, Hyung Koo; University of Nebraska: Christopher Kratochvil, Diane May, Randy LaGrone, Martin Harrington; New York University: Anne Marie Albano, Glenn Hirsch, Tracey Knibbs, Emlyn Capili; University of Chicago/Northwestern University: Mark Reinecke, Bennett Leventhal, Catherine Nageotte, Gregory Rogers; Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center: Sanjeev Pathak, Jennifer Wells, Sarah Arszman, Arman Danielyan; University of Oregon: Anne Simons, Paul Rohde, James Grimm, Lananh Nguyen; University of Texas Southwestern: Graham Emslie, Beth Kennard, Carroll Hughes, Maryse Ruberu; Wayne State University: David Rosenberg, Nili Benazon, Michael Butkus, Marla Bartoi. Greg Clarke (Kaiser Permanente) and David Brent (University of Pittsburgh) are consultants; James Rochon (Duke University Medical Center) is statistical consultant.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure: Susan Silva is a consultant with Pfizer. John March is a consultant or scientific advisor to Pfizer, Lilly, Wyeth, GSK, Jazz, and MedAvante and holds stock in MedAvante; he receives research support from Lilly and study drug for an NIMH-funded study from Lilly and Pfizer; he is the author of the MASC. The other authors have no financial relationships to disclose.

References

- Asarnow J, Carlson G, Guthrie D. Coping strategies, self-perceptions, hopelessness, and perceived family environments in depressed and suicidal children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1987;55:361–366. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.55.3.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell AC, D'Zurilla TJ. Problem-solving therapy for depression: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review. 2009;29:348–353. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang E. Perfectionism and dimensions of psychological well-being in a college student population: A further test of a mediational model. 2002 Manuscript submitted for publication. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon W, Heppner P, Rudd M. Problem-solving appraisal, hopelessness, and suicidal ideation: Evidence for a mediational model. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1994;41:91–98. [Google Scholar]

- D'Zurilla T. Problem-solving therapy: A social competence approach to clinical intervention. Springer; New York: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- D'Zurilla T, Nezu A. Development and preliminary evaluation of the Social Problem-Solving Inventory. Psychological Assessment: A Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1990;2:156–163. [Google Scholar]

- D'Zurilla T, Sheedy C. Relation between social problem-solving ability and subsequent lack of psychological stress in college students. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1991;61:841–846. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.61.5.841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Zurilla TJ, Maydeu-Olivares A. Conceptual and methodological issues in social problem-solving assessment. Behavior Therapy. 1995;26:409–432. [Google Scholar]

- D'Zurilla T, Nezu A, Maydeu-Olivares A. Manual for the Social Problem-Solving Inventory-Revised. Multi-Health Systems; North Tonawanda, NY: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- D'Zurilla T, Chang E, Nottingham E, Faccini L. Social problem-solving deficits and hopelessness, depression, and suicidal risk in college students and psychiatric inpatients. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1998;54:1–17. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4679(199812)54:8<1091::aid-jclp9>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Zurilla T, Nezu A. Problem-solving therapy: A social competence approach to clinical intervention. 2nd ed. Springer; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- D'Zurilla TJ, Nezu AM. Problem-solving therapy: A positive approach to clinical intervention. 3rd ed Springer; New York: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon W, Heppner P, Rudd M. Problem-solving appraisal, hopelessness, and suicidal ideation: Evidence for a mediational model. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1994;41:91–98. [Google Scholar]

- Fremouw W, Callahan T, Kashden J. Adolescent suicidal risk: Psychological, problem-solving, and environmental factors. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 1993;23:46–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland A, Harrington J, House R, Scott J. A pilot study of the relationship between problem-solving skills and outcome in major depressive disorder. British Journal of Medical Psychology. 2000;73:303–309. doi: 10.1348/000711200160525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haaga D, Fine J, Terrill D, Stewart B, Beck A. Social problem-solving deficits, dependency, and depressive symptoms. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 1993;19:147–158. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton KE, Dobson KS. Cognitive therapy of depression: Pretreatment patient predictors of outcome. Clinical Psychology Review. 2002;22:875–893. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(02)00106-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heppner P, Kampa M, Brunning L. The relationship between problem-solving self-appraisal and indices of physical and psychological health. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 1987;11:155–168. [Google Scholar]

- Joiner T, Gencoz T, Faruk G, Rudd D. Can positive emotion influence problem-solving attitudes among suicidal adults? Journal of Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2001;32:507–512. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy P. A Guide to Econometrics. 5th Edition MIT Press; Cambridge: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer HC, Wilson GT, Fairburn CG, Agras WS. Mediators and moderators of treatment effects in randomized clinical trials. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59:877–884. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.10.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner M, Clum G. Treatment of suicide ideators: A problem-solving approach. Behavior Therapy. 1990;21(4):403–411. [Google Scholar]

- Nezu A, Ronan G. Life stress, current problems, problem-solving and depression symptoms: An integrative model. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53:693–697. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.5.693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nezu A, Ronan G. Social problem-solving as a moderator of stress related depressive symptoms: A prospective analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1988;35:134–138. [Google Scholar]

- Nezu A, D'Zurilla T. Social problem solving and negative affective states. In: Kendall PC, Watson D, editors. Anxiety and depression: Distinctive and overlapping features. Academic Press; New York: 1989. pp. 285–315. [Google Scholar]

- Pozanski E, Mokros H. Children's Depression Rating Scale. 1995 Revised (CDRS-R) Manual. [Google Scholar]

- Reinecke M, DuBois D, Schultz T. Social problem solving, mood, and suicidality among inpatient adolescents. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2001;25:743–756. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds WM. Professional Manual for the Reynolds Adolescent Depression Scale. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Rotheram-Borus M, Trautman P, Dopkins S, Shrout P. Cognitive style and pleasant activities among female adolescent suicide attempters. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1990;58:554–561. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.58.5.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rude S, Rehm L. Response to treatments for depression: The role of initial status on targeted cognitive and behavioral skills. Clinical Psychology Review. 1991;11:493–514. [Google Scholar]

- Sadowski C, Kelly M. Social problem solving in suicidal adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1993;61:121–127. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.61.1.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadowski C, Moore LA, Kelley M. Psychometric properties of the Social Problem Solving Inventory (SPSI) with normal and emotionally disturbed adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1994;22:487–500. doi: 10.1007/BF02168087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva SG, Jacobs RJ, Curry JF, Kennard BD, McNulty S, et al. Adherence to the pharmacologic and psychosocial interventions in the Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS) Submitted to the American Journal of Psychiatry. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- Simons A, Gordon J, Monroe S, Thase M. Toward an integration of psychological, social, and biologic factors in depression: Effects on outcome and course of cognitive therapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1995;63:369–377. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.3.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snow R. Aptitude-treatment interaction as a framework for research on individual differences in psychotherapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1991;59:205–216. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.2.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sotsky S, Glass D, Shea M, Pilkonis P, Collins J, Elkin I, et al. Patient predictors of response to psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy: Findings in the NIMH Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1991;148:997–1008. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.8.997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Specken A, Hawton K. Social Problem Solving in Adolescents with Suicidal Behavior: A Systematic Review. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2005;35(4):365–387. doi: 10.1521/suli.2005.35.4.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spirito A, Overholser J, Stark L. Common problems and coping strategies: II. Findings with adolescent suicide attempters. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1989;17:213–221. doi: 10.1007/BF00913795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study Team Fluoxetine, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and their combination for adolescents with depression: Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS) randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;292:807–820. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.7.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel A, Brown G, Beck A. Cognitive therapy for suicidal adolescents. In: Wenzel A, Brown G, Beck A, editors. Cognitive Therapy for Suicidal Patients: Scientific and Clinical Applications. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC, US: 2009. pp. 235–262. [Google Scholar]