Abstract

In ectodermal explants from Xenopus embryos, inhibition of BMP signaling is sufficient for neural induction, leading to the idea that neural fate is the default state in the ectoderm. Many of these experiments assayed the action of BMP antagonists on animal caps, which are relatively naïve explants of prospective ectoderm, and different results have led to debate regarding both the mechanism of neural induction and the appropriateness of animal caps as an assay system. Here we address whether BMP antagonists are only able to induce neural fates in pre-patterned explants, and the extent to which neural induction requires FGF signaling. We suggest that some discrepancies in conclusion depend on the interpretations of sox gene expression, which we show not only marks definitive neural tissue, but also tissue that is not yet committed to neural fates. Part of the early sox2 domain requires FGF signaling, but in the absence of organizer signaling, this domain reverts to epidermal fates. We also reinforce the evidence that ectodermal explants are naïve, and that explants that lack any dorsal prepattern are readily neuralized by BMP antagonists, even when FGF signaling is inhibited.

Keywords: Xenopus, Sox2, neural induction, BMP antagonist, β-catenin, SU5402

Introduction

BMP antagonists induce neural fates in ectodermal explants (animal caps) that would normally give rise to epidermis, without inducing mesoderm as an intermediary. Because endogenous BMP signaling induces epidermis in unmanipulated animal caps, and caps can be converted to a neural fate by blocking BMP signaling, a “default model” for neural development was proposed (Green, 1994; Hemmati-Brivanlou and Melton, 1997). The default model argues that in the absence of any other signaling, ectodermal tissue will develop as neural. In Xenopus, several lines of evidence support this model. Animal cap cells that are dissociated and then re-aggregated will spontaneously express neural markers, a capacity that is suppressed by addition of BMP protein, suggesting that washing away the endogenous extracellular BMP ligands is all that is required for neuralization of ectoderm (Grunz and Tacke, 1989; Wilson and Hemmati-Brivanlou, 1995). Any manipulation that reduces BMP signaling also neuralizes animal caps (reviewed in Hemmati-Brivanlou and Melton, 1997). Xenopus tropicalis embryos depleted of BMP antagonists lose expression of all differentiated neural markers (Khokha et al., 2005), while Xenopus laevis embryos depleted of BMP2, 4,7 and ADMP or β-catenin express neural markers radially throughout the ectoderm (Reversade and De Robertis, 2005; Reversade et al., 2005).

However, the default model is still debated. In the chick, overexpression of a BMP antagonist in the prospective epidermal region is not sufficient to induce expression of neural markers, although transplantation of the chick organizer, Hensen’s node, will induce neural gene expression (Streit et al., 1998; Linker and Stern, 2004; Linker et al., 2009). Overexpression of FGF will induce some neural markers in chick epiblast, in a fashion that is independent of BMP antagonism (Streit et al., 2000). In the frog, there is also evidence that blocking BMP signaling is not sufficient for neural induction in epidermal regions that are separated from the neural plate, but the addition of FGF signaling will neuralize such regions (Linker and Stern, 2004; Delaune et al., 2005; Wawersik et al., 2005). Indeed, FGF addition can induce posterior neural fates in animal cap explants, but only under conditions where BMP signaling is also moderated, suggesting cooperation between these pathways (Kengaku and Okamoto, 1995; Lamb and Harland, 1995). Alternative manipulations, such as suppression of Nodal signaling, will also synergize with BMP inhibition to induce neuralization (Chang and Harland, 2007). A mechanism for integration of FGF signaling with BMP antagonism has been proposed in which FGF signals transduced through MAPK result in phosphorylation of the Smad1 linker region (Uzgare et al., 1998; Pera et al., 2003; Sapkota et al., 2007). However, this would still not explain why other means of BMP antagonism are insufficient for neural induction in the chick epiblast, and so FGF signaling is considered to act independently of BMP antagonists in that context.

Because of the interplay between BMP antagonists and FGF signaling in neural development, several experimental approaches have been used to investigate the requirement for FGFs in neural induction, and the degree to which BMP antagonists and FGFs can act independently as neural inducers. These have yielded conflicting results. Initial experiments using a truncated FGF type I receptor (XFD) suggested that FGF signaling was required for the development of all neural tissue, as well as for the neuralization response of animal caps to Bmp antagonists (Launay et al., 1996; Sasai et al., 1996). However, subsequent experiments using XFD concluded that neural induction by Bmp antagonists was independent of FGFs, while supporting a role for FGFs in posterior neural development (McGrew et al., 1997; Barnett et al., 1998). Later experiments using a dominant negative Ras (N17Ras) reinforced the conclusion that neural induction by Bmp antagonists did not require FGF signaling, or MAP kinase activation (Ribisi et al., 2000). More recently, the role of FGFs in neural induction has been revisited using small molecule inhibitors specific for the FGF pathway. The FGF receptor inhibitor SU5402 has been shown to inhibit posterior neural development as well as mesoderm induction, while anterior neural development is retained except at very high doses of inhibitor, where specificity becomes difficult to demonstrate (Delaune et al., 2005; Fletcher and Harland, 2008). The consensus arising from these loss-of-function studies is that posterior development is dependent on FGF signaling, but the role of FGFs in anterior neural development, and the independence of FGF and BMP antagonist mediated neural induction, continue to be controversial.

The historical conflict among interpretations of experimental results in different model systems may arise either from the default model incompletely describing neural induction, from limitations in the assays used to study neural induction, or from real differences in the mechanism of neural induction in different species. In this study, we address some experimental contexts that have led to uncertainty over the activity of BMPs, their antagonists and FGFs in neural induction in Xenopus. Notably we have addressed to what extent the conventional early neural markers sox2 and sox3 definitively measure neural commitment. We address whether residual sox gene expression in embryos depleted of organizer or of BMP antagonists represents definitive neural tissue, and we exploited explants from radially ventralized embryos to address whether neural induction can occur in the absence of a neural border. We show that sox2 and other pre-neural genes may not represent the best markers for committed neural fate, and that definitive neural markers should also be assayed in studies of neural induction. Because ventralized and normal caps behave in a similar fashion, we argue that animal caps are a naïve tissue appropriate for studies of neural induction in Xenopus, and that in this tissue, neural induction can be considered a default state achieved through BMP inhibition.

Materials and Methods

Embryo Culture and microinjection

Xenopus laevis

Xenopus laevis eggs were collected, fertilized, and embryos were cultured by standard procedures (Sive, 2000), embryos were staged according to (Nieuwkoop and Faber, 1967), and microinjected with mRNA as described previously (Sive, 2000).

Plasmids used for mRNA synthesis:

Noggin: CS2+X. laevis Noggin (linearized with Not1, transcribed with Sp6)

MStrawberry (to trace injection): CS107+mStrawberry (linearized with Not1, transcribed with Sp6)

Bcl-XL: X. tropicalis Bcl-XL/bcl-2 like mRNA (Image clone 5309043) was linearized with Cla1 and transcribed using Sp6.

Xenopus tropicalis

Xenopus tropicalis eggs were collected onto glass dishes coated with Liebowitz’s L15 medium supplemented with 10% calf serum. Testes were macerated on ice in L15+10% calf serum, and added immediately to eggs. After 2 minutes, fertilized eggs were flooded with 1/9 MR containing 3% Ficoll 400. Embryos were dejellied 30–60 minutes after fertilization in 1/9 MR+ 3% cysteine. Embryos were cultured in 1/9 MR or 1/20 MR supplemented with 0.1 mg/ml gentamicin sulfate. For additional details see (Khokha et al., 2002).

Morpholino oligonucleotide design and microinjection

Morpholino oligonucleotides (Gene Tools, LLC) were designed to block translation of X. tropicalis or X. laevis gene products

Morpholino oligo sequences used:

β-catenin: 5’ TTTCAACCGTTTCCAAAGAACCAGG 3’ (Heasman et al., 2000)

Follistatin: 5’ ACATCCTCAGTGCTGGGAGTGGGAC 3’ (this study)

Chordin 1: 5’ ACGTTCTGTCTCGTATAGTGAGCGT 3’

Chordin 2: 5’ ACAGCATTTTTGTGGTTGTCCCGAA 3’(Oelgeschlager et al., 2003)

Noggin: 5’ TCACAAGGCACTGGGAATGATCCAT 3’(Kuroda et al., 2004)

Ectodermal explants (animal caps)

X. laevis embryos were cultured to stage 9 in 1/3 MR, and vitelline envelopes were removed using #5 watchmaker’s forceps. 300–400 micron square ectodermal explants (animal caps) were excised using the Gastromaster (XENOTEK Engineering), using yellow tips at the highest setting, or by using #5 watchmaker’s forceps. Excised animal caps were cleared of adhering yolky cells, then cultured on dishes coated with 2% agarose in 3/4 NAM supplemented with 0.1mg/ml gentamicin sulfate until the desired stage.

SU5402 treatment

SU5402 (Calbiochem) was resuspended in DMSO to a concentration of 25mM. X. laevis embryos were treated by soaking in 1/3 MR plus 50µg/mL gentamicin sulfate, with SU5402. Two batches of SU5402 were used, and the effective dose was determined empirically for each, as assayed by loss of xbra staining and embryo morphogenesis defects. Control embryos were treated with the equivalent percentage of DMSO without SU5402. Injected or control embryos were raised to 32 cells in 1/3MR plus 3% Ficoll 400, then transferred to SU5402 or DMSO-containing media. Embryos were treated in 96 well plates, with 3–4 embryos per well in a volume of 150µl. Plates were wrapped in aluminum foil to prevent degradation of SU5402, and embryos were raised to the desired stage, rinsed in 1/3 MR, then fixed in MEMFA or digested for RT-PCR. For ectodermal explants, 32-cell stage embryos were transferred to 1/3 MR containing SU5402 or DMSO, and cultured until stage 8. Embryos were transferred into 3/4 NAM to excise explants, and the explants were allowed to heal for 20–30 minutes before being transferred to 3/4 NAM containing SU5402 or DMSO and raised to the desired stage in the dark. Effort was made to minimize the time embryos spent out of SU5402, and embryos that spent greater than 45 minutes total time outside of SU5402 were discarded. As a control, whole embryos were processed in the same way and found to have no xbra staining.

Whole mount in situ hybridization

Embryos were developed to the desired stage and then fixed in MEMFA for 2–6 hours at room temperature or overnight at 4°C. X. laevis in situ hybridization with Digoxygenin-labeled RNA probes used a mutibasket technique as described (Sive, 2000). X. tropicalis in situ hybridization was similar, with minor differences as described in (Khokha et al., 2002).

RT-PCR

Injected or uninjected embryos or animal caps of the desired stage were digested using an RNA lysis buffer containing Proteinase K (5mM EDTA, 50mM Tris pH 7.5, 50mM NaCl, 0.5% SDS, 250ug/ml PK). 200µl were used per embryo or 10 animal caps. Embryos were digested for 1 hour at 42°C, phenol/chloroform extracted and precipitated with ethanol and sodium acetate. Pellets were resuspended in DEPC-treated water, treated with DNAse 1 for 1 hour at 37°C, phenol/chloroform extracted again, and RNA was precipitated with ammonium acetate and ethanol. RNA pellets were resuspended in DEPC-treated water, random hexamers added, and reverse transcription was carried out using MMLV reverse transcriptase (Promega). Genomic DNA contamination was assayed by using an aliquot of whole-embryo uninjected RNA processed without reverse transcriptase (labeled RT- in each experiment). PCR on the resulting cDNA was carried out for 30 cycles with an annealing temperature of 55°C unless otherwise indicated. PCR products were separated on 1.6% agarose gels and visualized with ethidium bromide. Ornithine decarboxylase was used as a loading control for all RT-PCRs. ODC primers were designed to a region of the transcript with identity between X. tropicalis and X. laevis, and that flank a small intron, so that any genomic DNA contamination could be identified in each sample.

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR

Quantitative RT-PCR analysis used SYBR green (BioRad) and the BioRad iCycler PCR machine and software. cDNA samples were prepared as for non-quantitative PCR, with the exception that all mRNA amounts were quantified prior to reverse transcription such that 1ug of mRNA was used for each RT reaction. 1ul of the resulting DNA was used in each 25 uL PCR reaction, together with 10uM primer mix and SyBR green reaction mix diluted to a final concentration of 1×. The PCR reaction was as follows: 95° for 5 minutes, 40 repeats with each repeat consisting of 95° for 30s, 55° for 30s, 72° for 30s. This was followed by 72° for 7 minutes and a melt curve of 10s cycles increasing by 0.5 degrees from 55° to 95°. After data collection, melt curves were inspected to ensure a single peak was present for each primer. Threshold amplification values (ct) were assigned by the iCycler analysis software, and these were converted to expression values using whole embryo cDNA as a reference sample following (Zhu et al., 2007). For sox2 and nrp, expression values were normalized to odc expression levels by dividing by the relative expression of odc for that sample as compared to the whole embryo sample. Reported expression levels are the result of three experimental repeats. Error bars represent standard deviations.

RT-PCR primers used:

-

ODC

F: TTTGGTGCCACCCTTAAAAC,

R: CCCATGTCAAAGACACATCG;

-

NCAM (Kintner and Melton, 1987)

F: CACAGTTCCACCAAATGC,

R:GGAATCAAGCGGTACAGA;

-

NRP1(Kim et al., 1997)

F:GGGTTTCTTGGAACAAGC,

R:ACTGTGCAGGAACACAAG;

-

Sox2 (Liu and Harland, 2005)

F:CAACCAGAGGATGGACACTTATGC,

R:TGGATTCCGACTTGACTACCGAG

TUNEL Staining

Embryos were raised to late neurula stages, fixed in MEMFA and dehydrated in Methanol prior to TUNEL staining (Hensey and Gautier, 1998)using NBT/BCIP substrate. TdT enzyme was from Invitrogen and digoxigenin-dUTP was from Roche.

Results

Sox2 is expressed in ventralized embryos

In a previous study, we found that X. tropicalis embryos depleted of the Bmp antagonists Follistatin, Chordin, and Noggin (FCN morphants) did not have a morphological neural plate, but retained expression of the pre-neural transcripts sox2 and sox3 in a ring around the blastopore (Khokha et al., 2005). To better characterize the expression of neural markers in a ventralized context, we injected X. laevis embryos with a morpholino oligonucleotide designed to block translation of β-catenin mRNA. β-catenin morphants do not express organizer genes, and develop with a radially ventralized morphology, lacking dorsoanterior structures (Heasman et al., 2000). Despite the absence of an organizer, we found that β-catenin morphants express sox2 at late gastrula and early to mid-neurula stages, and that this expression is confined to a ring around the blastopore similar to that observed in X. tropicalis FCN morphants (Figure 1A). This ring of sox2 expression fades at late neurula stages and is absent by stage 19. A similar pattern of expression is observed for sox3 (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. Ventralized embryos express residual sox2 and sox3.

X. laevis embryos were injected in both blastomeres at the two cell stage with β-catenin MO, then raised to the stage indicated, fixed in MEMFA, dehydrated and stained by in situ hybridization for expression of sox2 (A) or sox3 (B). Uninjected control sibling embryos are shown at right for each stage. For β-catenin morphants, a ring of sox2 expression is evident around the blastopore between stages 14 and 16, which fades and has disappeared by stage 19. The same pattern is seen for sox3. Embryos are shown in dorsal views with anterior to the top.

Definitive neural markers are not expressed in ventralized embryos

To better understand what the ring of sox2 expression in β-catenin morphants represents, we examined the expression of several markers of differentiated neural tissue in β-catenin morphants. These included nervous system-specific RNP protein (NRP1) (Richter et al., 1990) neural cell adhesion marker (NCAM), and nervous system-specific β-tubulin (Richter et al., 1988). We consider these genes to be definitive markers of neural fate, because they are expressed in maturing neural tissue or differentiating neurons. In control embryos, these genes begin to be expressed at neurula stages (Figure 2A), but they are not expressed in β-catenin morphants at any stage analyzed. Because the ring of sox2/sox3 expression eventually disappears from β-catenin morphants, and because these ventralized embryos do not go on to express definitive neural markers in this tissue, we consider that sox2 does not mark committed neural tissue. It likely instead marks a pre-neural state, or a state that is competent to be stably neuralized by additional signals, consistent with its described role in stem cells.

Figure 2. Ventralized embryos do not express markers of differentiated neural tissue.

X. laevis embryos were injected in both blastomeres at the two cell stage with β-catenin MO, then raised to the stages indicated, fixed in MEMFA and analyzed by in situ hybridization for expression of differentiated neural markers, the organizer markers chordin and gsc, or fgf8. Uninjected control sibling embryos are shown to the left. A) ncam, nrp1 and n-tubulin are not expressed in β-catenin morphants. Among stage 14 β-catenin morphants, expression was observed in 0/10 embryos for ncam, 0/10 embryos for nrp, and 0/9 embryos for n-tubulin. At stage 16, expression was observed in 1/12 embryos for ncam, 0/10 embryos for nrp, and 0/10 embryos for n-tubulin. At stage 18, expression was observed in 0/32 embryos for ncam, 0/31 embryos for nrp, and 1/34 embryos for n-tubulin. The two embryos expressing detectable ncam or n-tubulin had morphologically normal neural plates, suggesting that they received a low dose of β-catenin MO. B) fgf8 is expressed in a ring around the blastopore in β-catenin morphants at stage 14, in a pattern similar to that seen for sox2. This expression fades by stage 18. C) Gastrula-stage β-catenin morphants do not express the organizer markers chordin or gsc (For chordin, 0/8 morphants showed expression, and 0/9 morphants expressed gsc) Embryos in A and B are shown in dorsal views with anterior to the top, while embryos in C are shown in vegetal views with dorsal to the top.

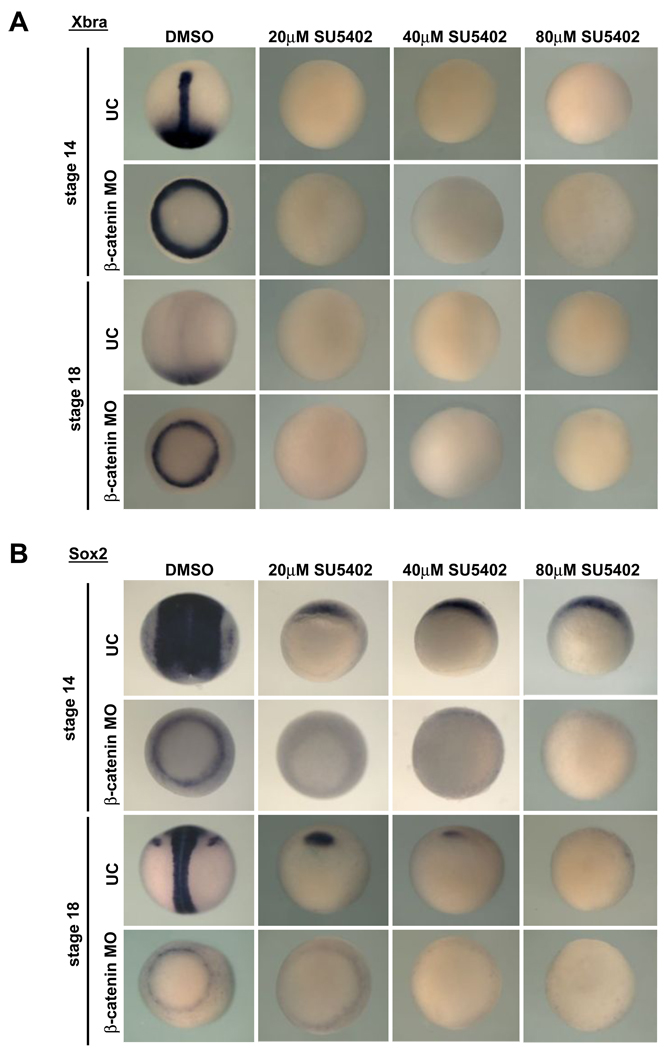

The sox2 expression in ventralized embryos is dependent on FGF signaling

Because β-catenin morphants do not express organizer genes, including many Bmp antagonists (Heasman et al., 2000; Xanthos et al., 2002; Khokha et al., 2005)(Figure 2C), we addressed the basis for the sox2 expression that was retained in these embryos. FGFs also induce expression of neural genes, and are required for normal posterior neural development (Rentzsch et al., 2004; Delaune et al., 2005), and so FGF signaling was a likely candidate for regulating this circumblastoporal sox2 expression. Indeed, β-catenin morphants express fgf8 in a transient pattern similar to that of sox2, supporting this hypothesis (Figure 2B). To test this hypothesis, we incubated β-catenin morphants in the FGF receptor inhibitor SU5402. β-catenin morphants raised in SU5402 do not express sox2, supporting the hypothesis that this expression is FGF-dependent (Figure 3). The efficacy of our SU5402 treatments in inhibiting FGF signaling was confirmed by assaying xbra expression, which was eliminated in SU5402-treated uninjected embryos (Figure 3). Interestingly, we noted that uninjected embryos treated with SU5402 retained some sox2 expression dorsally, suggesting that not all endogenous sox2 expression is FGF-dependent (Figure 3), which may be expected from observations that organizer genes are still expressed, though transiently, in SU5402-treated embryos (Fletcher and Harland, 2008).

Figure 3. The sox2 expressed in β-catenin morphants is FGF-dependent.

X. laevis embryos were injected with β-catenin MO and cultured in SU5402 to the stage indicated, then fixed and assayed for expression of xbra (A) or sox2 (B). A) Control uninjected DMSO-treated embryos express xbra in the notochord and posterior mesoderm at stage 14, and in the posterior mesoderm only at stage 18. This expression is lost in embryos treated with the Fgf receptor inhibitor SU5402. β-catenin morphants treated with DMSO express xbra in a ring around the blastopore at stages 14 and 18, and this expression is also lost with SU5402 treatment. B) Expression of sox2 in uninjected embryos is reduced by SU5402 treatment, although small amounts of sox2 expression are retained anteriorly for all doses of SU5402 at stage 14, and for all but the highest doses of SU5402 at stage 18. In β-catenin embryos, sox2 is expressed in a ring around the blastopore, which is very sensitive to SU5402 and is lost even at low SU5402 doses both at stage 14 and 18.

Sox2 is not expressed in X. laevis FCN morphants

In a previous study, we demonstrated that X. tropicalis embryos depleted of the Bmp antagonists Follistatin, Chordin, and Noggin (FCN morphants) did not express neural markers or develop dorsal structures (Khokha et al., 2005). Although these morphants did not have a neural plate, they did express sox2 in a ring similar to that described here for β-catenin morphants. The later effects of BMP antagonist depletion were difficult to study in X. tropicalis, because these embryos underwent large-scale apoptosis at neurula stages. Although such apoptosis could be rescued by microinjection of mRNA encoding the anti-apoptotic factor bcl-XL (Supplementary Figure 1) or by noggin mRNA injection (data not shown), we found it was simpler to analyze the phenotypes of X. laevis FCN morphants, which survive to early tailbud stages without additional manipulation. Surprisingly, we found that sox2 is not detectable in X. laevis FCN morphants (Figure 4). Because of the similarity between sox2 expression in FCN depleted X. tropicalis and β-catenin- depleted X. laevis, we were surprised to see a stronger effect on sox2 expression in X. laevis FCN morphants. The absence of sox2 staining in X. laevis morphants cannot be ascribed to embryo death or poor general embryo quality, because these FCN morphants still express epidermal keratin strongly (91.7% with strong circumferential expression of cytokeratin, N=24)(Figure 4). The expression of cytokeratin in these morphants does not directly abut the perimeter of the blastopore, and blastopore closure in these morphants is somewhat impaired. We note that xbra remains broadly and strongly expressed around the blastopore of late neurula FCN morphants (100%, N=12)(Figure 4), suggesting that mesoderm may be poorly internalized during gastrulation in these embryos, which would account for both observations.

Figure 4. X. laevis FCN morphants do not express sox2.

X. laevis embryos were injected in each blastomere at the 2 cell stage with 20ng each of follistatin, chordin, and noggin MOS. Embryos were raised to the stage indicated, fixed in MEMFA, and stained for expression of sox2 or epidermal cytokeratin. A) Some embryos expressed low levels of sox2, but this expression was not seen in a ring. Most FCN morphants do not express sox2. The fraction of embryos falling into each class of sox2 expression are shown in the lower right corner. B) Cytokeratin is expressed strongly in FCN morphants at all stages assayed, but is excluded from the blastopore and adjacent tissue (22/24 embryos with strong circumferential expression). C) Xbra expression is expanded in neurula stage FCN morphants. Embryos are shown in dorsal views with anterior to the top.

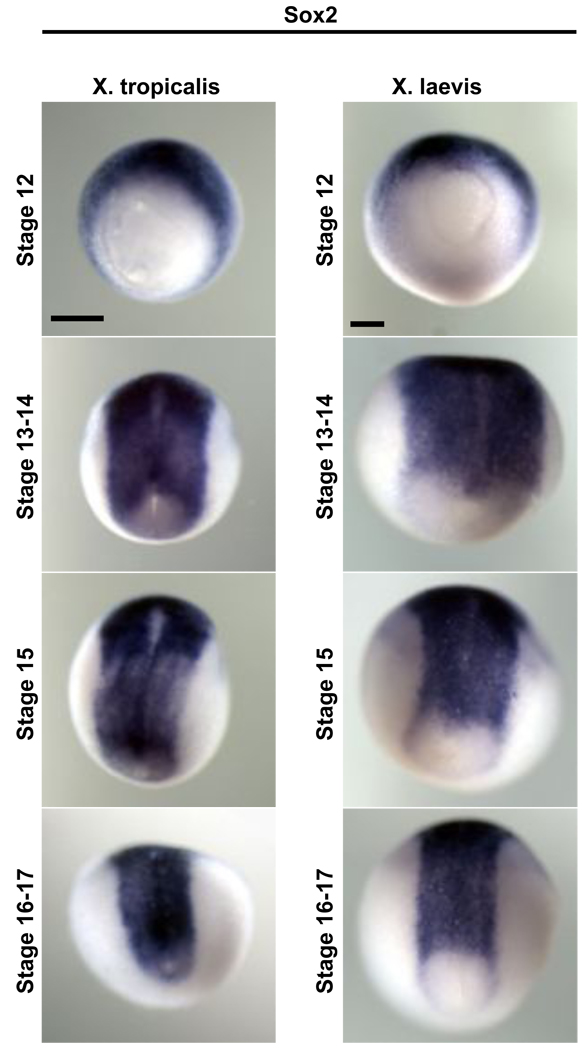

We also observed a subtle difference in the endogenous pattern of sox2 expression between X. laevis and X. tropicalis (Figure 5). In X. tropicalis, sox2 is expressed strongly all around the blastopore at neurula stages, whereas in X. laevis, this circumblastoporal expression is weak, and does not approach the margin of the blastopore as closely as it does in X. tropicalis. It is likely that the residual expression of sox2 that is observed in X. tropicalis FCN morphants is derived from this circumblastoporal region of expression. Because X. laevis embryos do not normally express sox2 strongly in this region, no sox2 expression would therefore be observed in FCN morphants, accounting for the observation that X. tropicalis FCN morphants retain a ring of sox2 expression while X. laevis morphants do not. In any case, the absence of sox2 expression in X. laevis FCN morphants supports the conclusion that these organizer-inhibited embryos completely lack a neural plate.

Figure 5. sox2 has slightly different endogenous expression in X. tropicalis and X. laevis.

X. tropicalis or X. laevis embryos were raised to the stage indicated, fixed in MEMFA and analyzed by in situ hybridization for expression of sox2. In X. tropicalis, sox2 expression closes posteriorly around the blastopore, and is tightly adjacent to the blastopore margin. In X. laevis, posterior circumblastoporal expression of sox2 is weak. All embryos are shown in dorsoposterior views with anterior to the top; the embryos have been rotated slightly to clearly show the blastopore.

We also tested whether residual neural gene expression seen in the X. tropicalis FCN morphants is transient, like the transient expression in β-catenin morphants. Indeed, we do observe a loss of sox3 and other neural gene expression in the extreme class of FCN morphants in late-neurula X. tropicalis, when the cell death is prevented by injection of bcl-XL mRNA (Supplementary Figure 1). These observations imply that the ring of sox2 expression observed in β-catenin morphants is of a slightly different derivation than the ring observed in FCN morphants, because this ring is observed in X. laevis β-catenin morphants but not X. laevis FCN morphants. The results also suggest that in X. laevis, circumblastoporal sox2 expression is strongly dependent on both BMP antagonists and FGFs.

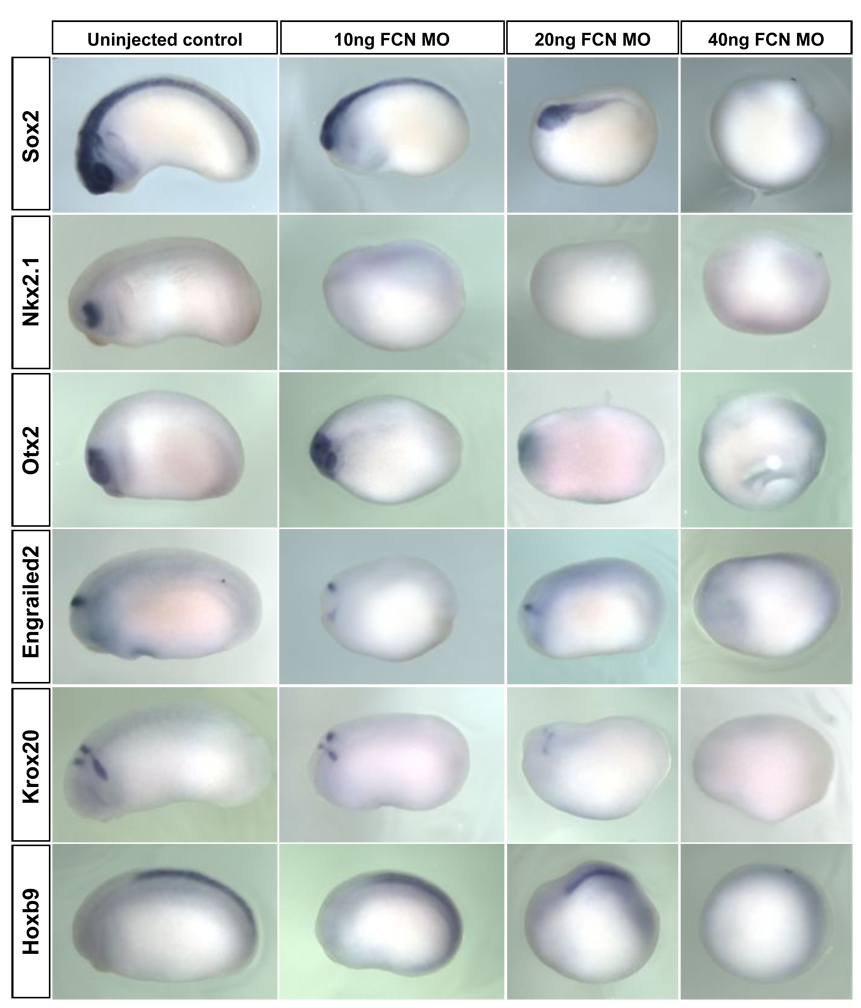

Anterior neural markers are more sensitive to the loss of BMP antagonists than posterior neural markers

The viability of X. laevis FCN morphants into late neurula stages, and the ability to rescue X. tropicalis FCN morphants with bcl-Xl mRNA allowed us to investigate the later effects of a loss of Bmp antagonists on embryonic patterning. While embryos injected with high doses of FCN MOs had no neural plate, lower doses elicit a range of BMP antagonist activity, whose effect could be assayed using regional-specific markers. Previous experiments using UV-irradiated embryos that had undergone different amounts of cortical rotation, or were rescued with different amounts of organizer, showed that small amounts of organizer signaling lead to only posterior neural fates, while full organizer activity is needed for anterior development (Stewart and Gerhart, 1990). Similarly, targeted injection of a β-catenin morpholino into two dorsal blastomeres at the 8-cell stage leads to a reduction of head structures in most embryos, although a dorsal-ventral axis is still specified, suggesting that anterior structures are more sensitive to a loss of organizer signaling than posterior structures (Heasman et al., 2000). We found that a stepwise reduction in BMP antagonists led to a similar result, in which anterior neural markers were more sensitive to the loss of BMP antagonists than posterior neural markers. Embryos injected with a low dose of FCN MOs express all A/P markers assayed except the forebrain marker nkx2.1 (0% express nkx2.1, n=12)(Figure 6), supporting the hypothesis that the most anterior neural markers are especially sensitive to loss of Bmp antagonists. At intermediate doses of FCN MOs, expression was reduced for the midbrain/hindbrain border marker en2 (reduced in 80% of embryos, n=10), the hindbrain marker krox20 (82%, n=11), and the forebrain/midbrain marker otx2 (87%, n=15), while the spinal cord marker hoxb9 is still strongly expressed (100%, n=12). sox2 is weakly expressed in a thin stripe (100%, n=22). At high doses of FCN MOs, expression of all neural markers is lost. These data confirm that anterior neural markers are more sensitive to the loss of BMP antagonists than posterior markers.

Figure 6. Anterior neural markers are more sensitive to the loss of Bmp antagonists than posterior neural markers.

X. laevis embryos were injected at the two cell stage with increasing doses of Follisatin, Chordin, and Noggin MOs. Embryos were injected in both blastomeres at the two-cell stage; doses indicated refer to the total dose of MO injected into the embryo. Embryos were raised to stage 22, fixed and analyzed by in situ hybridization for expression of the genes indicated. nkx2.1 marks the ventral forebrain and is lost in embryos injected with low doses of FCN MOs. The forebrain/midbrain marker otx2, midbrain/hindbrain boundary marker en2 and rhombomeres 3/5 marker krox20 have reduced expression in embryos injected with low or intermediate doses of MO, and are lost in embryos injected with a high dose of MOs. The spinal cord marker hoxB9 is expressed strongly in embryos injected with low or intermediate doses of MO and is lost in embryos injected with a high dose of MO. Embryos are shown in lateral views with anterior to the left.

Ventralized embryos and animal caps do not express neural border markers

Our experiments using the β-catenin morpholino and BMP antagonist morpholinos support a model of neural induction in which BMP antagonism and FGF signaling act as separable inputs into early sox2 expression. β-catenin morphants express a ring of sox2 that is FGF-dependent. Embryos depleted of BMP antagonists lose normal expression of sox2, and the sensitivity of neural markers to the loss of BMP antagonists is greater for anterior than posterior markers. However, we have not yet addressed the implications of these data on the default model of neural induction. Is induction of neural tissue achieved as the simple derepression of a default state, or does ectoderm require pre-existing or coincident additional patterning signals to respond to BMP antagonists? Much of the work framing the default model has relied upon experiments carried out in animal caps, which have been assumed to be a naïve tissue. This simple view of animal caps has been called into question by data demonstrating that animal cap cells are normally fated to populate the neural border, and that BMP antagonism is not sufficient for a conversion of ventral epidermis to neural fate (Streit et al., 1998; Linker and Stern, 2004; Linker et al., 2009). Based on such results, it was proposed that animal caps, like chick epiblast explants, might have a pre-neural or neural border character that is required for their neuralization in response to BMP antagonists (Linker et al., 2009). To investigate whether animal caps possess a prospective neural border, we assayed expression of neural border genes in animal caps. We found that animal caps cut from uninjected embryos do not express the neural border markers pax3 (0%, n=22), hairy2a (0%, n=18), zic2 (0%, n=21), or the neural crest marker slug (8% with weak expression, 92% with no expression, n=24)(Figure 7), although they strongly express the epidermal marker cytokeratin (100%, n=36). Neural border markers are weakly induced in animal caps by low doses of Noggin. This suggests that unlike chick epiblast explants, Xenopus animal caps do not have neural border character, at least in terms of molecular marker expression, although they support the idea that neural border character can be induced in response to Noggin.

Figure 7. Xenopus ectodermal explants and ventralized embryos do not express neural border markers.

Uninjected control X. laevis embryos, β-catenin morphants, and animal caps cut from blastula stage uninjected or noggin-injected embryos were cultured to stage 20 and assayed for expression of the neural border markers pax3, hairy2a, and zic2, and the neural crest marker slug. Expression of these genes was not detected in animal caps or β-catenin morphants (of β-catenin morphants, 0% expressed hairy2a (n=14), pax3 (n=15), and zic2 (n=14), while 6% expressed slug weakly (n=16). All four genes had some expression in animal caps cut from embryos injected with 1pg of noggin mRNA (63% for hairy2a, n=8; 50% for pax3, n=10; 79% for slug, n=14; and 67% for zic2, n=9). The epidermal marker cytokeratin is strongly expressed in β-catenin morphants but excluded from the blastopore. Cytokeratin is strongly expressed in both injected and uninjected animal caps, but was somewhat weaker in noggin-injected animal caps. Embryos are shown in dorsal views with anterior to the left.

Ectodermal explants from ventralized embryos are neuralized in reponse to Noggin

Recent experiments have also suggested that only ectoderm that has direct cellular contact with the neural border can be neuralized by BMP antagonists, and that animal caps fit this criterion because they are derived from an area of ectoderm that will normally contribute to the neural border (Linker et al., 2009). However, this model appears to conflict with early data describing the neural inductive properties of Noggin in animal caps cut from UV-ventralized embryos. These ventralized caps are still competent to respond to Noggin by expressing neural markers (Lamb et al., 1993; Knecht et al., 1995). We therefore revisited the properties of neural induction by BMP antagonists in embryos ventralized by β-catenin knockdown. In late-neurula (stage 20–22) embryos injected with a β-catenin morpholino, markers of the neural border and neural tube are not expressed (Figure 7, Figure 8A). We injected embryos with the β-catenin MO at the two cell stage, and then re-injected them in the animal pole at the 4 cell stage with 1 or 10pg of noggin mRNA. At stage 9 (late blastula), we cut animal caps from these ventralized, Noggin-injected embryos, raised them to early tailbud stages and assayed their expression of neural markers. Animal caps cut from Noggin-injected β-catenin morphants strongly express both sox2 and definitive neural markers, as assayed both by in situ hybridization and by RT-PCR (Figure 8). Animal caps cut from Noggin-injected embryos were as likely or more likely to express sox2 or nrp when cut from β-catenin morphants as when cut from control Noggin-injected embryos (Figure 8B, C). This suggests that a neural border fate or dorso-anterior fate is not required for Xenopus animal cap ectoderm to respond to Noggin.

Figure 8. Ectodermal explants derived from ventralized embryos are neuralized by Noggin.

A) X. laevis embryos were injected in both blastomeres at the two cell stage with β-catenin MO, then re-injected in the animal pole at the 4 cell stage with 1 or 10pg of noggin mRNA. At stage 9, animal caps were cut, and cultured to stage 24. Animal caps from β-catenin morphants and control embryos injected with noggin mRNA were analyzed by in situ hybridization for expression of sox2 and nrp1. Animal caps cut from β-catenin noggin injected morphants were equally likely to express sox2 and nrp1 as caps cut from embryos injected with noggin mRNA alone. B, C) Quantification of the results shown in (A). A repeat of the experiment gave similar results. D) Animal caps cut from β-catenin morphants injected with noggin mRNA also strongly express both sox2 and definitive neural markers as assayed by non-quantitative RT-PCR.

FGF signaling is not required for neuralization by Noggin in animal caps

The ability of Noggin to neuralize ectodermal explants derived from ventralized embryos suggests that pre-conditioning neural border signals are not required for BMP antagonists to neuralize. However, it does not clarify whether other signals may be required for ectodermal tissue to respond to BMP antagonists. Because FGF signaling is known to play a significant role in neural induction, we considered that FGF signaling might be required for ectoderm to be able to convert to a neural fate. This seemed particularly relevant in our study because fgf8 is still expressed in β-catenin morphants (Figure 2), suggesting that FGF signaling is likely occurring in these embryos. To address the possibility that neuralization of ectoderm by Noggin requires FGF signaling, we examined the ability of Noggin to induce expression of neural markers in ectodermal explants in the absence of FGF signaling. We injected noggin mRNA into the animal pole of 4-cell stage embryos, and cultured them in the FGF receptor antagonist SU5402 beginning at the 32-cell stage (several hours before the onset of zygotic transcription). At stage 8 (mid-blastula), animal caps were excised from these embryos, and the embryos were again cultured in SU5402 until early tailbud stages. SU5402 treated explants cut from noggin-injected embryos still strongly express the definitive neural marker nrp as assayed by in situ hybridization (Figure 9A). We also noted that whole embryos cultured in SU5402 expressed a small amount of nrp, again suggesting that not all endogenous neural gene expression is FGF-dependent (Figure 9A). Because these embryos were removed from SU5402 briefly for cap cutting, we verified the efficacy of SU5402 in this treatment protocol by confirming loss of xbra expression in gastrula-stage whole embryos that were treated in the same way (Figure 9C). However, we noticed that in explants from embryos injected with noggin mRNA, β-catenin MO and treated with SU5402, in situ hybridization staining of nrp was weaker than in embryos injected only with noggin mRNA. Because the β-catenin MO did not reduce neural gene expression in the absence of SU5402 (Figure 8) this led us to test whether high doses of SU5402 might compromise embryo or explant health. Indeed, we found that treatment with 100µM SU5402 led to widespread apoptosis in neurula stage embryos, as assayed by TUNEL staining (Figure 9B). To correct for the effects of damaged tissue, we assayed expression of nrp and sox2 using non-quantitative and quantitative RT-PCR. When the amounts of overall gene expression were normalized to levels of ornithine decarboxylase expression (odc), we found that SU5402 treated β-catenin MO and noggin mRNA injected animal caps expressed comparable levels of sox2 and nrp to caps injected with noggin mRNA alone (Figure 9D–G). We conclude that animal caps are therefore competent to be neuralized in the absence of endogenous dorsal signals, and also when FGF signaling is suppressed well below the level required for activation of its target gene xbra or for proper gastrulation and convergence extension movements. Previously, it has been reported that at very high levels of SU5402, all neural gene expression is lost (Delaune et al., 2005). We find that embryos treated doses of inhibitor in excess of 80µM die or have impaired tissue integrity, and find that very high levels of Su5402 lead to widespread apoptosis, complicating analysis by in situ hybridization

Figure 9. Ectodermal explants do not require FGF signaling to be neuralized by Noggin.

A) X. laevis embryos were injected in both blastomeres at the two cell stage with β-catenin MO, then re-injected in the animal pole at the 4 cell stage with 1 or 10pg of noggin mRNA. Embryos were cultured in SU5402 or 0.32% DMSO from the 32 cell stage until stage 8. At stage 8, animal caps were cut, returned to SU5402 or DMSO, and cultured to stage 24. Whole embryos treated with increasing levels of SU5402 from stage 9 to late neurula stages were stained for apoptotic nuclei using TUNEL (B). 93% of embryos treated with 100υM SU5402 had widespread TUNEL staining (n=15). Animal caps from β-catenin morphants and control embryos injected with noggin mRNA were analyzed by in situ hybridization for expression of nrp (A), or by RT-PCR for expression of nrp, and sox2 (D). Ornithine decarboxylase (ODC) was used as a loading control. The efficiency of this SU5402 treatment protocol was confirmed by assaying expression of xbra at stage 11 (C). 0% of Su5402 treated embryos expressed xbra (n=36). Expression of nrp and sox2 was also quantified using quantitative RT-PCR (F, G) and normalized to ODC expression. Animal caps cut from SU5402 treated, noggin-injected embryos still express nrp and sox2 at comparable levels to animal caps from noggin injected embrys treated only with DMSO This is also true of animal caps cut from noggin-injected, β-catenin injected, SU5402 treated embryos.,

Discussion

Sox2 and Sox3 are not exclusively markers of definitive neural tissue

The mechanism of neural induction in vertebrate embryos and the relative contributions of different signaling pathways to neural fate commitment have been a matter of ongoing controversy. The default model of neural induction was first proposed over 15 years ago, and since that time, the mechanisms of gastrula stage patterning and the transcriptional networks involved in neural patterning have undergone extensive elaboration, and many new markers of neural fate have been used. One potential source of discrepancy in results can be the molecular marker used to score neural fate. In the chick and in the zebrafish, sox2 and sox3 have been used as markers of definitive neural fate (Kudoh et al., 2004; Linker and Stern, 2004; Rentzsch et al., 2004; Papanayotou et al., 2008). However, in addition to their persistent expression in the neural tube, sox2 and sox3 are also expressed in pluripotent cells and stem cells, suggesting that they might also be considered neural competence markers, and only later as definitive neural markers (Wegner and Stolt, 2005; Rossant and Tam, 2009). Our data support a model of sox2 as a pre-neural transcript that is not necessarily a marker of committed neural fate. This is most clearly supported by the observation that ventralized embryos express sox2 but do not express markers of differentiated neural tissue (Figure 1, 2).

Our data suggest that sox2 expression has at least two inputs: FGF signaling, and BMP antagonists. FGF signaling is required for expression of sox2 around the blastopore and is required for expression of sox2 in ventralized embryos (Figure 3). BMP antagonists are required for sustained expression of sox2 in embryos (Figure 4, Supplemental figure 1), and are sufficient for expression of sox2 in animal caps (Figure 8, 9). These inputs are separable. sox2 is still strongly expressed in ectoderm that is treated with BMP antagonists but in which FGF signaling is inhibited (Figure 9), and residual sox2 expression is also found in ventralized embryos depleted of β-catenin, where organizer genes are not expressed but FGF signaling is still present (Figure 1). Interestingly, the regulation of sox2 may be slightly different in X. tropicalis and X. laevis, as residual sox2 expression is seen in X. tropicalis depleted of BMP antagonists (Khokha et al., 2005), but not in X. laevis (Figure 4), and the endogenous patterns of sox2 expression differ slightly between these two species (Figure 5).

BMP antagonists and anterior-posterior neural patterning

The role of BMP antagonists in neural induction has been explored through numerous gain-of-function studies. Recently, a growing body of loss-of-function data in multiple species has also emerged in support of their importance for proper neural patterning. We have shown that in Xenopus laevis, the BMP antagonists Follistatin, Chordin and Noggin are required for neural plate formation, as they are in Xenopus tropicalis. We also suggest that anterior neural tissue is more sensitive to the loss of Bmp antagonists than posterior neural tissue. Several mechanisms may explain this increased sensitivity of anterior markers to BMP antagonists. Studies in mice and in X. tropicalis have suggested a specific requirement for BMP antagonists in forebrain development, a finding that is supported by our data (Bachiller et al., 2000; Kim and Pleasure, 2003; Wills et al., 2006). However, a progressive loss of anterior to posterior structures also arises from decreasing organizer size (Gerhart et al., 1989; Stewart and Gerhart, 1990), or decreasing induction of dorsal mesoderm (Gerhart and Keller, 1986; Gimlich, 1986). Targeted injection of a β-catenin morpholino into two dorsal blastomeres at the 8-cell stage results mainly in a loss of anterior structures, though a dorsal/ventral axis is still formed (Heasman et al., 2000), supporting the idea that anterior structures are especially sensitive to a loss of organizer signaling. Although BMP antagonists have sometimes been considered to be trunk and tail inducers, because of their inefficient induction of anterior structures in whole embryos, they all induce anterior structures in explants. Thus the likely explanation for the inability to induce a complete axis is likely due to the dominant caudalizing effect of the marginal zone, such that when the organizer is inhibited, the dorsal tissues fail to undergo adequate morphogenetic movements to escape these posterior signals (Gerhart et al., 1989), namely FGF and Wnt signaling. In X. tropicalis FCN morphants, expression of the BMP target gene vent2 is expanded into the organizer region at early gastrula stages (Khokha et al., 2005), demonstrating that organizer function is decreased by FCN knockdown. As BMP antagonists are depleted, a greater fraction of the remaining prospective neural plate marked by sox2 expression would be expected to be influenced by FGF signaling, and its posteriorizing activity (Cox and Hemmati-Brivanlou, 1995; Lamb and Harland, 1995; Christen and Slack, 1997; Fletcher et al., 2006). Therefore as the balance of neural induction shifts from BMP antagonist mediated to FGF influenced, one would expect the remaining neural tissue to take on a progressively posteriorized character, until all BMP antagonist activity is lost, and no neural tissue can be stably induced.

A dorsalized or neural border pre-pattern is not required for neuralization

Findings that cell-autonomous BMP antagonists such as Smad6 or a truncated type I Bmp receptor fail to induce neural tissue in an epidermal context have suggested that additional signals are needed for neural induction in normal development. Such additional signals may include FGF for posterior neural development (Linker and Stern, 2004; Delaune et al., 2005; Wawersik et al., 2005), or Lefty and Cerberus-mediated suppression of Nodal signaling, which in the epidermal context can cooperate with BMP blocking to execute anterior programs of neural development (Chang and Harland, 2007). Wnts and FGFs may also regulate the net amount of BMP signaling though GSK3 or MAPK mediated phosphorylation of the Smad1 linker region (Fuentealba et al., 2007; Sapkota et al., 2007). However, it has also been proposed that a neural border prepattern is required for BMP antagonists to induce neural tissue (Linker et al., 2009). Cell autonomous BMP antagonists induce a neural border state in the ventral ectoderm, but this does not progress to definitive neural tissue (Wawersik et al., 2005; Chang and Harland, 2007), showing this state is not a sufficient precondition for antagonists to induce neural tissue in this assay. It has also been argued that animal caps contain a neural border prepattern that is essential for animal caps to be neuralized by BMP antagonists. In Xenopus, there is a prepattern in the animal cap, which depends on earlier cortical rotation and activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling, and this can promote sensitivity to neural or dorsal mesodermal inductions (Sharpe et al., 1987; Sokol and Melton, 1991; Bolce et al., 1992), but such a prepattern is not needed for neural induction. Not only do animal caps not express neural border markers, unless BMPs are inhibited (Figure 7, (Knecht et al., 1995), but if caps are cut from embryos ventralized by UV irradiation, or by β-catenin depletion, neither of which develop a neural border, noggin is still able to induce neural markers (Figure 7, 8; (Lamb et al., 1993; Knecht et al., 1995)). We therefore argue that no prepattern is required for Xenopus animal cap tissue to be neuralized by BMP antagonists.

FGF signaling and BMP antagonism play separable roles in neural induction

Although BMP antagonists have been shown to be necessary and sufficient for neural induction in some contexts, they have also been clearly demonstrated not to be sufficient to convert non-neural ectoderm to a neural fate in other contexts. Blocking BMP signaling in the chick prospective epidermis is not sufficient to induce neural marker expression (Streit et al., 1998; Linker and Stern, 2004; Linker et al., 2009). Even in Xenopus, misexpression of BMP antagonists in the ventral epidermis is not sufficient for a conversion to neural fate, while FGF signaling can overcome this limitation (Linker and Stern, 2004; Delaune et al., 2005; Wawersik et al., 2005). However, suppression of Nodal signaling together with suppression of BMP signaling also allows expression of neural markers in Xenopus ventral ectoderm (Chang and Harland, 2007). It seems likely that tissues unable to respond to BMP antagonism may have undergone extra pre-patterning or signaling rendering them less naïve to neural inducing signals, when compared to animal caps. In these contexts, FGF signaling or Nodal inhibition may play an essential role in restoring competence to express neural markers.

Apart from their roles in initial neural induction, BMP antagonists and FGF signaling also have distinct properties in neural patterning. BMP antagonists induce expression of anterior neural markers, and additional signaling by FGFs, Retinoic acid, or Wnts is required to impose posterior identity. FGF8a has specifically been shown to be required in posterior neural patterning (Fletcher et al., 2006). Our data support FGF signaling as an essential component of neural development in Xenopus, and demonstrate that FGF signaling is required for the normal expression of sox2, particularly in the circumblastoporal region away from the organizer. However, the induction of neural fate by BMP antagonists can proceed in the absence of FGF signaling (Figure 9), and the anterior neural plate is not sensitive to the loss of FGF signaling but very sensitive to the loss of BMP antagonists (Figure 3, 6, 9). This separability of FGF signaling from BMP antagonism in Xenopus neural induction likely differs in some respects from the situation in zebrafish. Expression of BMP antagonists (specifically chordin) is dependent upon FGF signaling in zebrafish (Maegawa et al., 2006; Varga et al., 2007), whereas in Xenopus BMP antagonists are still expressed transiently in FGF-depleted embryos (Fletcher and Harland, 2008). When the expression of BMP antagonists in FGF-depleted zebrafish embryos was restored by delaying SU5402 treatment until after the onset of organizer gene expression or by overexpression of Noggin, anterior neural genes were expressed (Rentzsch et al., 2004), consistent with our model in which anterior neural expression is independent of FGF signaling. While our data also corroborate the requirement for FGF signaling in posterior neural induction, we do not find that posterior neural induction is fully independent of BMP antagonists, because posterior neural genes are not expressed in embryos treated with high doses of BMP antagonist MOs.

Taken together, our data support a model of Xenopus neural induction in which BMP antagonists and FGF signals contribute together to the normal expression of sox genes in the prospective neural plate and circumblastoporal region. BMP antagonists are essential for commitment of this tissue to a definitive neural fate, and can act independently of FGFs to induce anterior neural fates. FGFs are essential for posterior neural gene expression, and FGF signaling is sufficient for circumblastoporal expression of sox2 and sox3, although BMP antagonists are required for their maintenance. At high doses, SU5402 has been shown to eliminate sox2 expression (Delaune et al., 2005). Although we do not observe a complete loss of neural markers at doses of SU5402 that are sufficient to eliminate expression of xbra and impair gastrulation movements, we can not absolutely rule out a requirement for small residual levels of FGF signaling for sox2 expression, in part because higher doses of SU5402 result in embryo death (Figure 9). However, we do show that in embryos where FGF signaling is inhibited such that FGF target genes are not expressed, ectodermal tissue remains competent to neuralize in response to Bmp antagonists (Figure 9). We therefore favor a model in which BMP antagonists can act as neural inducers independent of FGF signaling.

Supplementary Material

X. tropicalis embryos were injected in each blastomere at the two cell stage with 20ng each of Chordin, Noggin, and Follistatin MOs, and with 200pg bcl-XL mRNA. A–C) Examples of embryos injected with FCN MOs, and coinjected with bcl-XL mRNA. D–F) Stage 25 embryos were scored for apoptotic cell nuclei by TUNEL. Coinjection with bcl-XL mRNA reduced the number of TUNEL positive cells in FCN morphants. G) FCN morphant embryos were scored for tissue integrity, which was improved by coinjection of bcl-XL mRNA. H) Embryos were raised to stage 24 and assayed for molecular marker expression. Expression of neural markers was reduced or lost. Where available, the fraction of embryos falling into each phenotypic class

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Russell Fletcher for comments and experiments that informed this study, and to members of the Harland lab for advice and discussion. We also thank Hui Zhang and Rakhi Gupta of the Baker lab at Stanford University for advice and assistance with quantitative RT-PCR. This work was supported by NIH GM49346; AEW was supported by the Center for Integrative Genomics.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bachiller D, Klingensmith J, Kemp C, Belo JA, Anderson RM, May SR, McMahon JA, McMahon AP, Harland RM, Rossant J, De Robertis EM. The organizer factors Chordin and Noggin are required for mouse forebrain development. Nature. 2000;403:658–661. doi: 10.1038/35001072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett MW, Old RW, Jones EA. Neural induction and patterning by fibroblast growth factor, notochord and somite tissue in Xenopus. Dev Growth Differ. 1998;40:47–57. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-169x.1998.t01-5-00006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolce ME, Hemmati-Brivanlou A, Kushner PD, Harland RM. Ventral ectoderm of Xenopus forms neural tissue, including hindbrain, in response to activin. Development. 1992;115:681–688. doi: 10.1242/dev.115.3.681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C, Harland RM. Neural induction requires continued suppression of both Smad1 and Smad2 signals during gastrulation. Development. 2007;134:3861–3872. doi: 10.1242/dev.007179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christen B, Slack JM. FGF-8 is associated with anteroposterior patterning and limb regeneration in Xenopus. Dev Biol. 1997;192:455–466. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox WG, Hemmati-Brivanlou A. Caudalization of neural fate by tissue recombination and bFGF. Development. 1995;121:4349–4358. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.12.4349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaune E, Lemaire P, Kodjabachian L. Neural induction in Xenopus requires early FGF signalling in addition to BMP inhibition. Development. 2005;132:299–310. doi: 10.1242/dev.01582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher RB, Baker JC, Harland RM. FGF8 spliceforms mediate early mesoderm and posterior neural tissue formation in Xenopus. Development. 2006;133:1703–1714. doi: 10.1242/dev.02342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher RB, Harland RM. The role of FGF signaling in the establishment and maintenance of mesodermal gene expression in Xenopus. Dev Dyn. 2008;237:1243–1254. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuentealba LC, Eivers E, Ikeda A, Hurtado C, Kuroda H, Pera EM, De Robertis EM. Integrating patterning signals: Wnt/GSK3 regulates the duration of the BMP/Smad1 signal. Cell. 2007;131:980–993. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.09.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerhart J, Danilchik M, Doniach T, Roberts S, Rowning B, Stewart R. Cortical rotation of the Xenopus egg: consequences for the anteroposterior pattern of embryonic dorsal development. Development. 1989;107 Suppl:37–51. doi: 10.1242/dev.107.Supplement.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerhart J, Keller R. Region-specific cell activities in amphibian gastrulation. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1986;2:201–229. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.02.110186.001221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gimlich RL. Acquisition of developmental autonomy in the equatorial region of the Xenopus embryo. Dev Biol. 1986;115:340–352. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(86)90254-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green JB. Roads to neuralness: embryonic neural induction as derepression of a default state. Cell. 1994;77:317–320. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90145-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunz H, Tacke L. Neural differentiation of Xenopus laevis ectoderm takes place after disaggregation and delayed reaggregation without inducer. Cell Differ Dev. 1989;28:211–217. doi: 10.1016/0922-3371(89)90006-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heasman J, Kofron M, Wylie C. Beta-catenin signaling activity dissected in the early Xenopus embryo: a novel antisense approach. Dev Biol. 2000;222:124–134. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemmati-Brivanlou A, Melton D. Vertebrate neural induction. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1997;20:43–60. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.20.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hensey C, Gautier J. Programmed cell death during Xenopus development: a spatio-temporal analysis. Dev Biol. 1998;203:36–48. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.9028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kengaku M, Okamoto H. bFGF as a possible morphogen for the anteroposterior axis of the central nervous system in Xenopus. Development. 1995;121:3121–3130. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.9.3121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khokha MK, Chung C, Bustamante EL, Gaw LW, Trott KA, Yeh J, Lim N, Lin JC, Taverner N, Amaya E, Papalopulu N, Smith JC, Zorn AM, Harland RM, Grammer TC. Techniques and probes for the study of Xenopus tropicalis development. Dev Dyn. 2002;225:499–510. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khokha MK, Yeh J, Grammer TC, Harland RM. Depletion of three BMP antagonists from Spemann's organizer leads to a catastrophic loss of dorsal structures. Dev Cell. 2005;8:401–411. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim AS, Pleasure SJ. Expression of the BMP antagonist Dan during murine forebrain development. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2003;145:159–162. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(03)00213-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim P, Helms AW, Johnson JE, Zimmerman K. XATH-1, a vertebrate homolog of Drosophila atonal, induces a neuronal differentiation within ectodermal progenitors. Dev Biol. 1997;187:1–12. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kintner CR, Melton DA. Expression of Xenopus N-CAM RNA in ectoderm is an early response to neural induction. Development. 1987;99:311–325. doi: 10.1242/dev.99.3.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knecht AK, Good PJ, Dawid IB, Harland RM. Dorsal-ventral patterning and differentiation of noggin-induced neural tissue in the absence of mesoderm. Development. 1995;121:1927–1935. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.6.1927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudoh T, Concha ML, Houart C, Dawid IB, Wilson SW. Combinatorial Fgf and Bmp signalling patterns the gastrula ectoderm into prospective neural and epidermal domains. Development. 2004;131:3581–3592. doi: 10.1242/dev.01227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroda H, Wessely O, De Robertis EM. Neural induction in Xenopus: requirement for ectodermal and endomesodermal signals via Chordin, Noggin, beta-Catenin, and Cerberus. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:E92. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb TM, Harland RM. Fibroblast growth factor is a direct neural inducer, which combined with noggin generates anterior-posterior neural pattern. Development. 1995;121:3627–3636. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.11.3627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb TM, Knecht AK, Smith WC, Stachel SE, Economides AN, Stahl N, Yancopolous GD, Harland RM. Neural induction by the secreted polypeptide noggin. Science. 1993;262:713–718. doi: 10.1126/science.8235591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Launay C, Fromentoux V, Shi DL, Boucaut JC. A truncated FGF receptor blocks neural induction by endogenous Xenopus inducers. Development. 1996;122:869–880. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.3.869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linker C, De Almeida I, Papanayotou C, Stower M, Sabado V, Ghorani E, Streit A, Mayor R, Stern CD. Cell communication with the neural plate is required for induction of neural markers by BMP inhibition: evidence for homeogenetic induction and implications for Xenopus animal cap and chick explant assays. Dev Biol. 2009;327:478–486. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.12.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linker C, Stern CD. Neural induction requires BMP inhibition only as a late step, and involves signals other than FGF and Wnt antagonists. Development. 2004;131:5671–5681. doi: 10.1242/dev.01445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu KJ, Harland RM. Inhibition of neurogenesis by SRp38, a neuroD-regulated RNA-binding protein. Development. 2005;132:1511–1523. doi: 10.1242/dev.01703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maegawa S, Varga M, Weinberg ES. FGF signaling is required for {beta}-catenin-mediated induction of the zebrafish organizer. Development. 2006;133:3265–3276. doi: 10.1242/dev.02483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrew LL, Hoppler S, Moon RT. Wnt and FGF pathways cooperatively pattern anteroposterior neural ectoderm in Xenopus. Mech Dev. 1997;69:105–114. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(97)00160-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwkoop PD, Faber J. "Normal Table of Xenopus laevis.". Amsterdam: North Holland Publishing Company; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Oelgeschlager M, Kuroda H, Reversade B, De Robertis EM. Chordin is required for the Spemann organizer transplantation phenomenon in Xenopus embryos. Dev Cell. 2003;4:219–230. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00404-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papanayotou C, Mey A, Birot AM, Saka Y, Boast S, Smith JC, Samarut J, Stern CD. A mechanism regulating the onset of Sox2 expression in the embryonic neural plate. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e2. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pera EM, Ikeda A, Eivers E, De Robertis EM. Integration of IGF, FGF, and anti-BMP signals via Smad1 phosphorylation in neural induction. Genes Dev. 2003;17:3023–3028. doi: 10.1101/gad.1153603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rentzsch F, Bakkers J, Kramer C, Hammerschmidt M. Fgf signaling induces posterior neuroectoderm independently of Bmp signaling inhibition. Dev Dyn. 2004;231:750–757. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reversade B, De Robertis EM. Regulation of ADMP and BMP2/4/7 at opposite embryonic poles generates a self-regulating morphogenetic field. Cell. 2005;123:1147–1160. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reversade B, Kuroda H, Lee H, Mays A, De Robertis EM. Depletion of Bmp2, Bmp4, Bmp7 and Spemann organizer signals induces massive brain formation in Xenopus embryos. Development. 2005;132:3381–3392. doi: 10.1242/dev.01901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribisi S, Jr., Mariani FV, Aamar E, Lamb TM, Frank D, Harland RM. Ras-mediated FGF signaling is required for the formation of posterior but not anterior neural tissue in Xenopus laevis. Dev Biol. 2000;227:183–196. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter K, Good PJ, Dawid IB. A developmentally regulated, nervous system-specific gene in Xenopus encodes a putative RNA-binding protein. New Biol. 1990;2:556–565. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter K, Grunz H, Dawid IB. Gene expression in the embryonic nervous system of Xenopus laevis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:8086–8090. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.21.8086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossant J, Tam PP. Blastocyst lineage formation, early embryonic asymmetries and axis patterning in the mouse. Development. 2009;136:701–713. doi: 10.1242/dev.017178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapkota G, Alarcon C, Spagnoli FM, Brivanlou AH, Massague J. Balancing BMP signaling through integrated inputs into the Smad1 linker. Mol Cell. 2007;25:441–454. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasai Y, Lu B, Piccolo S, De Robertis EM. Endoderm induction by the organizer-secreted factors chordin and noggin in Xenopus animal caps. Embo J. 1996;15:4547–4555. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharpe CR, Fritz A, De Robertis EM, Gurdon JB. A homeobox-containing marker of posterior neural differentiation shows the importance of predetermination in neural induction. Cell. 1987;50:749–758. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90333-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sive H. "Xenopus Laevis Cold Spring Harbor Manual.". 2000 [Google Scholar]

- Sokol S, Melton DA. Pre-existent pattern in Xenopus animal pole cells revealed by induction with activin. Nature. 1991;351:409–411. doi: 10.1038/351409a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart RM, Gerhart JC. The anterior extent of dorsal development of the Xenopus embryonic axis depends on the quantity of organizer in the late blastula. Development. 1990;109:363–372. doi: 10.1242/dev.109.2.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streit A, Berliner AJ, Papanayotou C, Sirulnik A, Stern CD. Initiation of neural induction by FGF signalling before gastrulation. Nature. 2000;406:74–78. doi: 10.1038/35017617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streit A, Lee KJ, Woo I, Roberts C, Jessell TM, Stern CD. Chordin regulates primitive streak development and the stability of induced neural cells, but is not sufficient for neural induction in the chick embryo. Development. 1998;125:507–519. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.3.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uzgare AR, Uzman JA, El-Hodiri HM, Sater AK. Mitogen-activated protein kinase and neural specification in Xenopus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:14833–14838. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varga M, Maegawa S, Bellipanni G, Weinberg ES. Chordin expression, mediated by Nodal and FGF signaling, is restricted by redundant function of two beta-catenins in the zebrafish embryo. Mech Dev. 2007;124:775–791. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2007.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wawersik S, Evola C, Whitman M. Conditional BMP inhibition in Xenopus reveals stage-specific roles for BMPs in neural and neural crest induction. Dev Biol. 2005;277:425–442. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegner M, Stolt CC. From stem cells to neurons and glia: a Soxist's view of neural development. Trends Neurosci. 2005;28:583–588. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills A, Harland RM, Khokha MK. Twisted gastrulation is required for forebrain specification and cooperates with Chordin to inhibit BMP signaling during X. tropicalis gastrulation. Dev Biol. 2006;289:166–178. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson PA, Hemmati-Brivanlou A. Induction of epidermis and inhibition of neural fate by Bmp-4. Nature. 1995;376:331–333. doi: 10.1038/376331a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xanthos JB, Kofron M, Tao Q, Schaible K, Wylie C, Heasman J. The roles of three signaling pathways in the formation and function of the Spemann Organizer. Development. 2002;129:4027–4043. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.17.4027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H, Gao W, Jiang H, Jin QH, Shi YF, Tsim KW, Zhang XJ. Regulation of acetylcholinesterase expression by calcium signaling during calcium ionophore A23187- and thapsigargin-induced apoptosis. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2007;39:93–108. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2006.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

X. tropicalis embryos were injected in each blastomere at the two cell stage with 20ng each of Chordin, Noggin, and Follistatin MOs, and with 200pg bcl-XL mRNA. A–C) Examples of embryos injected with FCN MOs, and coinjected with bcl-XL mRNA. D–F) Stage 25 embryos were scored for apoptotic cell nuclei by TUNEL. Coinjection with bcl-XL mRNA reduced the number of TUNEL positive cells in FCN morphants. G) FCN morphant embryos were scored for tissue integrity, which was improved by coinjection of bcl-XL mRNA. H) Embryos were raised to stage 24 and assayed for molecular marker expression. Expression of neural markers was reduced or lost. Where available, the fraction of embryos falling into each phenotypic class