Abstract

Loss of Drosophila mir-9a induces a subtle increase in sensory bristles, but a substantial loss of wing tissue. Here, we establish that the latter phenotype is largely due to ectopic apoptosis in the dorsal wing primordium, and we could rescue wing development in the absence of this microRNA by dorsal-specific inhibition of apoptosis. Such apoptosis was a consequence of de-repressing Drosophila LIM-only (dLMO), which encodes a transcriptional regulator of wing and neural development. We observed cell-autonomous elevation of endogenous dLMO and a GFP-dLMO 3'UTR sensor in mir-9a mutant wing clones, and heterozygosity for dLMO rescued the apoptosis and wing defects of mir-9a mutants. We also provide evidence that dLMO, in addition to senseless, contributes to the bristle defects of the mir-9a mutant. Unexpectedly, the upregulation of dLMO, loss of Cut, and adult wing margin defects seen with mir-9a mutant clones were not recapitulated by clonal loss of the miRNA biogenesis factors Dicer-1 or Pasha, even though these mutant conditions similarly de-repressed miR-9a and dLMO sensor transgenes. Therefore, the failure to observe a phenotype upon conditional knockout of a miRNA processing factor does not reliably indicate the lack of critical roles of miRNAs in a given setting.

Introduction

Dominant alleles of invertebrate genes associated with loss of 3' untranslated regions (3' UTRs) were harbingers of the existence of a regulatory universe mediated by ~22 RNAs known as microRNAs (miRNAs). For example, 3' UTR mutants of C. elegans lin-14 that induced defects in developmental timing were critical in illuminating its repression by the founding miRNA lin-4 (Lee et al., 1993; Wightman et al., 1991; Wightman et al., 1993). In addition, 3' UTR mutants of the Drosophila Notch pathway genes E(spl)m8 and Bearded, which affect eye and bristle specification (Klämbt et al., 1989; Leviten et al., 1997; Leviten and Posakony, 1996), permitted the 7-mer regulatory logic of miRNA binding sites to be elucidated (Lai, 2002; Lai et al., 1998; Lai and Posakony, 1997; Lai et al., 2005). These genes, along with a handful of targets analyzed more recently, demonstrate that the miRNA-mediated repression of certain genes can be critical to organismal phenotype (Flynt and Lai, 2008).

On the other hand, computational and quantitative profiling methods indicate that a majority of animal transcripts are directly targeted by one or more miRNAs, with individual miRNAs often targeting hundreds of transcripts via highly conserved binding sites (Bartel, 2009). Since the phenotypes of many miRNA loss-of-function mutants are relatively subtle (Smibert and Lai, 2008), presumably very few individual targets are regulated by miRNAs in a manner that is critically required for gross aspects of development or physiology (Flynt and Lai, 2008). Knowledge of such critical miRNA targets, whose slight overactivity is not tolerated, is especially relevant to understanding how miRNA dysfunction contributes to disease.

The development of Drosophila wings requires the coordinated action of several signaling pathways and positional information systems, which yield precise control over cell survival, proliferation, and specification (Cadigan, 2002; Milan and Cohen, 2000). Genetic analysis of mutants that perturb wing development revealed diverse insights into mechanisms of tissue patterning and growth, including many concepts that embody fundamental principles of gene regulation and animal development. Amongst Drosophila wing mutants, dominant Beadex (Bx) alleles causing loss of adult wing tissue were identified over 80 years ago (Mohr, 1927; Morgan, 1925). In the past decade, Bx mutants were recognized to result from gain-of-function of Drosophila LIM-only (dLMO) (Milán et al., 1998; Shoresh et al., 1998; Zeng et al., 1998). Curiously, most Bx alleles are caused by transposon insertions that disrupt its 3’ UTR, which hinted at critical post-transcriptional repression of dLMO. Another gene that affects wing development is mir-9a. Deletion of this highly conserved miRNA results in fully penetrant loss of posterior wing margin, along with a small number of ectopic sensory organs (Li et al., 2006).

In this report, we demonstrate a critical role for miR-9a in suppressing apoptosis in the developing wing, and show that the wing morphology defect of animals lacking this miRNA can be fully rescued by inhibiting apoptosis during wing development. While miR-9a has ~200 target genes that are deeply conserved across Drosophilid radiation (http://www.targetscan.org/), we find that its major functional requirement is to suppress dLMO in the developing wing pouch. We observed that dLMO is ectopically expressed in mir-9a mutant wing primordia, is directly repressed via its 3' UTR by endogenous miR-9a in the developing wing, and that heterozygosity for dLMO fully rescues the mir-9a wing defect. Our findings confirm and extend the recent report of dLMO as an important target of miR-9a in the wing (Biryukova et al., 2009), and collectively highlight the disproportionate functional impact of de-repressing certain transcripts within the collective pool of thousands of miRNA targets. Unexpectedly, the phenotype of miR-9a wing pouch clones is demonstrably stronger in certain respects than is clonal loss of the miRNA biogenesis factors Pasha and Dcr-1. This has consequences for interpreting the lack of certain phenotypes upon removing "all" miRNAs in certain settings.

Materials and methods

Drosophila strains

We used the following previously described strains: pasha[KO] (Martin et al., 2009); mir-9a stocks (mir-9a[J22], mir-9a[E39], and UAS-mir-9a) provided by Fen-Biao Gao (Li et al., 2006); senseless stocks (sens[E2], Lyra, and UAS-sens) obtained from Hugo Bellen (Nolo et al., 2000); dLMO stocks (Bx[1] and hdpR26, and UAS-dLMO) from Marco Milan (Milán et al., 1998); dcr-1[Q1147x] from Richard Carthew (Lee et al., 2004); and UAS-Diap1, UAS-p35, ptc-Gal4 and ap-Gal4 obtained from the Bloomington Stock Center. For clonal analysis, we recombined mir-9a alleles onto FRT80B and generated clones using hs-FLP (Bloomington Stock Center), vg-FLP (gift of Konrad Basler) or ubx-FLP (obtained from David Bilder). Clones were marked by absence of arm-lacZ (from Stephen Cohen) or ubi-GFP (Bloomington Stock Center).

UAS-DsRed-mir-9a was generated by amplifying the mir-9a locus with the following primers and cloning into pENTR (Invitrogen), and then transferring the insert into UAS-DsRed (Stark et al., 2003). miR-9A_F: CACCTAACTTAACATAAATAATAGAC; miR-9A_R: TCTAGATTGCCAAAGCAGTTGGCCG. The miR-9a sensor contained two antisense target sites, and was generated by annealing the oligos below and cloning into the NotI and XhoI restriction sites of tub-GFP-SV40 (gift of Julius Brennecke and Stephen Cohen). miR-9a sensor F Not: GGCCTCATACAGCTAGATAACCAAAGAAATCACACTCATACAGCTAGATAACCAAAG A; miR-9a sensor R Xho: TCGATCTTTGGTTATCTAGCTGTATGAGTGTGATTTCTTTGGTTATCTAGCTGTATGA. The dLMO sensor was made by amplifying the dLMO 3' UTR and ~200 bp downstream of the poly-adenylation signal from w[1118] genomic DNA using the oligos below, followed by cloning into the NotI and XhoI restriction sites of tub-GFP-SV40. dLMO UTR F Not: GATCgcggccgcAATAAAGCCCTGGGCATGGG; dLMO UTR R Xho: GATCctcgagTGCCCTCTAGCTCCTCTAGCTCC. Transgenic Drosophila were made using standard injection with delta2–3 helper transposase (BestGene Inc.) and multiple lines were analyzed for each construct.

Indirect immunofluorescence

To analyze imaginal discs, we used standard fixation in 4% paraformaldehyde, as described previously (Lai and Rubin, 2001). We used the following primary antibodies: mouse anti-Cut (1:10, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank-DSHB), guinea pig anti-Sens (1:2000, gift of Hugo Bellen), rat anti-dLMO (1:100, gift of Stephen Cohen), mouse anti-Wg (1:10, DSHB), rabbit anti-cleaved caspase-3 (1:50, Cell Signaling Technology), rabbit anti-GFP (1:600, Molecular Probes), mouse anti-βgalactosidase (1:10, DSHB). We used Alexa-488, -568 and -647-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:600, Molecular Probes).

Results

The major role of miR-9a during wing development is to suppress apoptosis

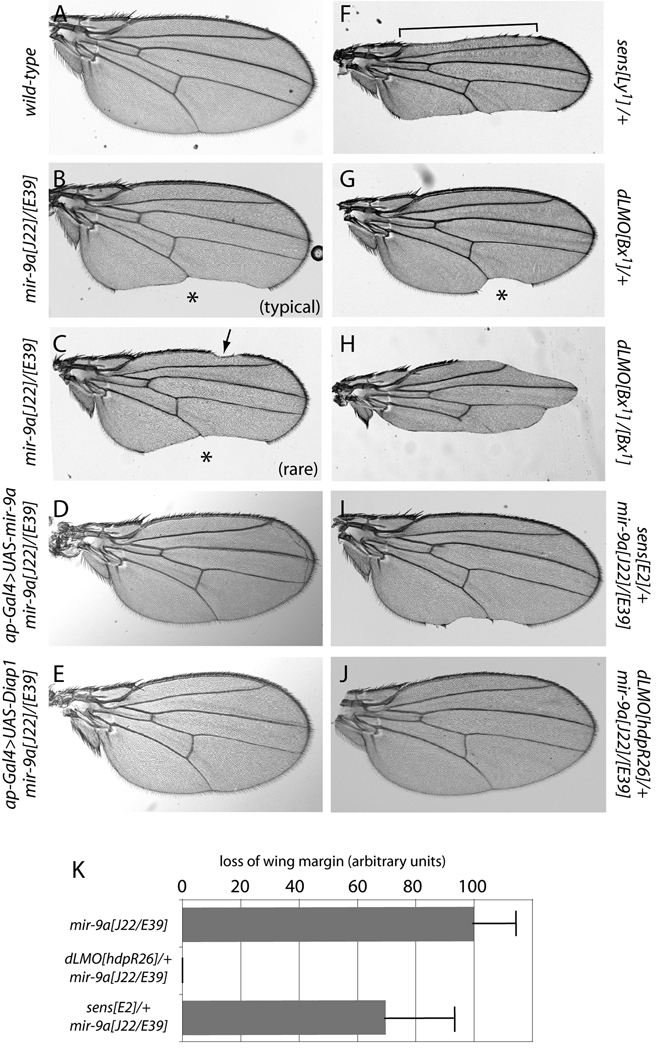

In contrast to their mild PNS defects, flies lacking mir-9a exhibit substantial and completely penetrant wing notching (Li et al., 2006). We examined the null alleles mir-9a[J22] and mir-9a[E39] in more detail, both as homozygotes and as trans-heterozygotes. All three genotypes lack ~50% of the posterior wing margin in all individuals (Fig. 1A, B), and a small fraction of animals (~10%) further exhibit mild loss of anterior wing margin (Fig. 1C). Thus, the posterior margin is more sensitive to miR-9a activity.

Figure 1.

Genetic interactions amongst mir-9a, senseless, and dLMO in wing morphology. Shown are wings of adult females, oriented with anterior to the top and posterior to the bottom. (A) Wild-type. (B) Transheterozygotes of mir-9a[J22]/[E39] null alleles exhibit completely penetrant notching along the posterior margin (asterisk). (C) About 10% of mir-9a[J22]/[E39] flies also show notching along the anterior wing margin (arrow). (D) Wing notching in mir-9a mutants can be rescued by reintroduction of miR-9a in the dorsal compartment using ap-Gal4. (E) Wing notching in mir-9a mutants can also be rescued by ectopic expression of Drosophila inhibitor of apoptosis 1 (Diap1). (F) Heterozygotes of the gain-of-function allele of senseless, Lyra[1], exhibit loss of both anterior (bracket) and posterior wing margin. (G) Heterozygotes of the gain-of-function allele of dLMO, Bx[1], show loss of only posterior margin (asterisk). (H) Bx[1] homozygotes exhibit loss of both anterior and posterior margin. (I) Heterozygosity for the null allele sens[E2] partially suppressed mir-9a wing notching. (J) Heterozygosity for the null allele dLMO[hdpR26] completely rescued mir-9a wing defects. (K) Quantification of wing margin loss; each bar depicts the mean and standard deviation across 50 female wings.

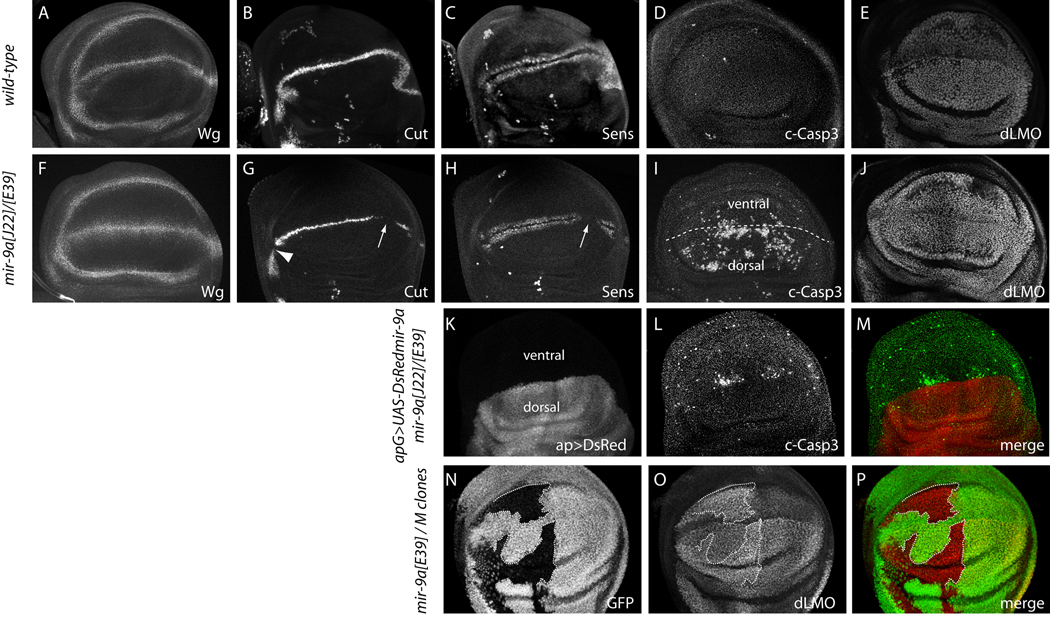

Notch pathway activity at the dorsoventral boundary of the wing pouch is necessary to activate Wingless signaling to specify wing margin cells. To assay whether this accounted for the mir-9a mutant phenotype, we examined the expression of Wingless (Wg), Cut, and Senseless (Sens) proteins. Wg serves as an early marker of specified wing margin cells, and its expression was normal in mir-9a mutant wing discs (Fig. 2A, F). On the other hand, we observed highly penetrant breaks in wing margin-associated Cut in the posterior compartment, and occasional gaps in anterior compartment (Fig. 2B, G). These patterns were consistent with the observed penetrance of adult wing notching (Fig. 1B, C). Cut-expressing cells induce the expression of Sens in two flanking rows of cells, and we observed corresponding breaks in Sens expression in mir-9a mutants (Fig. 2C, H).

Figure 2.

Cellular basis of mir-9a mutant phenotypes. All panels depict the wing pouch region of third instar wing imaginal discs stained for the indicated markers, oriented with anterior to the left, posterior to the right, ventral to the top and dorsal to the bottom. (A–E) Wildtype, (F–J) mir-9a[J22]/[E39], (K–M) ap-Gal4>UAS-DsRed-mir-9a in mir-9a[J22]/[E39], (N–P) mir-9a clones generated in hs-FLP; FRT80B M ubi-GFP/FRT80B mir-9a[J22]. The following panels are double stainings of the same tissue: B and C, G and H, F and I, K–M and N–P. (A, F) The expression of Wingless (Wg) is fairly normal in mir-9a mutants. (B, G) mir-9a mutants exhibit posterior breaks in Cut at the wing margin (arrow), and occasional anterior breaks (arrowhead). (C, H) mir-9a mutants exhibit breaks in wing margin-associated expression of Sens, particularly in the posterior compartment (arrow); the isolated stained cells are sensory organ precursors. (D, I) mir-9a mutants exhibit a high degree of apoptosis in the wing pouch as marked by cleaved Caspase-3 (c-Casp3), mostly in the dorsal compartment. (E, J) mir-9a mutants accumulate higher levels of dLMO. (K–M) Dorsal-specific expression of miR-9a suppresses the majority of the apoptotic defect of mir-9a mutants; a small amount of ectopic ventral apoptosis remains. (N–P) Clonal analysis using Minute technique demonstrates cell-autonomous elevation of dLMO in wing pouch cells lacking miR-9a.

Since expression of Wg at the wing margin was uninterrupted in the absence of miR-9a, we inferred that initially deficient margin specification was not the major cause of mir-9a wing loss. Another mechanism by which wing notching might arise is through excess cell death. We tested this by staining for apoptotic cells using antibodies that recognize cleaved (activated) caspase-3. In wildtype, only a small number of dying cells are seen in third instar wing imaginal discs (Fig. 2D). In contrast, we observed abundant cell death specifically in the wing pouch in all three mir-9a mutant genotypes, but not in the pro-notum region of the disc (Fig. 2I and data not shown). In summary, wing notching is the predominant morphological defect caused by lack of mir-9a, and this is associated with mildly defective margin specification and a high degree of ectopic cell death in the wing primordium.

Previously, the mir-9a wing defect was rescued by expressing a UAS-mir-9a transgene throughout the wing pouch using vg-Gal4 (Li et al., 2006). Curiously, we observed substantially more cell death in the dorsal compartment of the wing pouch, compared to the ventral compartment (Fig. 2I and Supplementary Fig. 1). We therefore asked whether the dorsal-specific expression of miR-9a was sufficient to rescue the loss of adult wing tissue. Indeed, activation of UAS-mir-9a using ap-Gal4, which is exclusively active in the dorsal compartment, completely restored the continuity of the adult wing margin in the mir-9a mutant (Fig. 1D). We used this regimen to check for the consequence of blocking cell death in mir-9a mutants. In fact, misexpression of either Drosophila inhibitor of apoptosis protein 1 (DIAP1) (Fig. 1E), or the baculovirus inhibitor of apoptosis P35 (data not shown) could fully rescue mir-9a wing notching. We clearly observed cell-autonomous rescue of apoptosis in these backgrounds, since the dorsal-specific activity of ap-Gal4 did not rescue ventral apoptosis in mir-9a mutants (Fig. 2K–M). Nevertheless, the small amount of remaining ectopic cell death was tolerated to permit the emergence of normal adult wings (Fig. 1E). We conclude that the main phenotypic requirement for Drosophila miR-9a is to suppress apoptosis in the wing primordium, and that dorsal wing development is especially sensitive to mir-9a dosage and apoptosis.

miR-9a represses dLMO to prevent apoptosis in the wing primordium

It was previously reported that miR-9a targets the zinc finger transcription factor encoded by senseless (sens) to control bristle and wing development (Li et al., 2006). The rationale was that ectopic Sens induces extra sensory organs and loss of wing margin (Fig. 1F) (Nolo et al., 2000; Nolo et al., 2001), similar to phenotypes seen in mir-9a loss-of-function animals. Notably, heterozygosity for sens[E58] could partially rescue mir-9a wing phenotypes, consistent with the inference of de-repressed Sens in this mutant (Li et al., 2006).

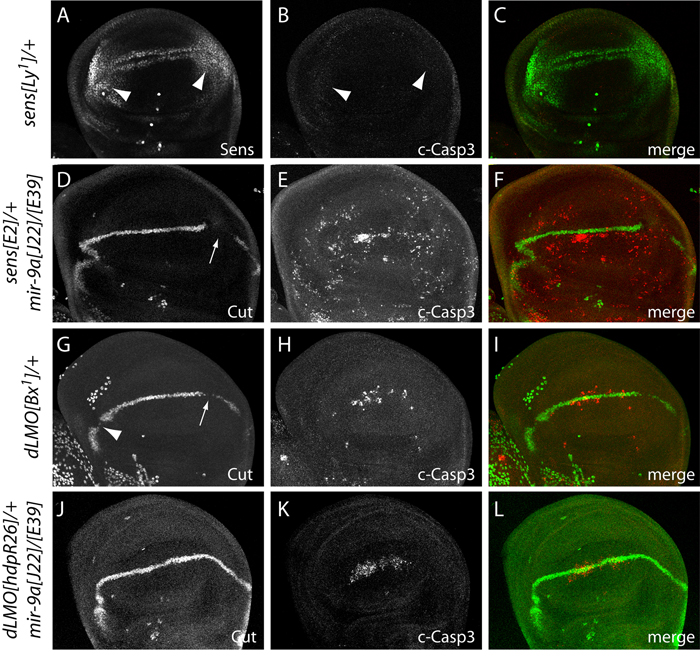

We tested this further by recombining the sens[E2] null allele with mir-9a alleles and evaluating genetic interactions. We observed a mild dominant suppression of wing notching (Fig. 1I), which we quantified in cohorts of 50 wings as a ~35% reduction of mir-9a-associated wing margin loss in the sens heterozygote (Fig. 1K). However, mir-9a mutant wing discs did not accumulate ectopic Sens in the third instar wing disc (Fig. 2H), during which time widespread apoptosis is manifest (Fig. 2I); Instead, we observed loss of wing margin-associated Sens in the posterior compartment. This contrasts with abundant ectopic Sens observed in the wing pouch in dominant alleles of sens that exhibit wing notching, referred to as Lyra mutants (Nolo et al., 2001), and with the observation that Lyra wing discs do not exhibit ectopic apoptosis (Fig. 3A–C).

Figure 3.

Rescue of mir-9a phenotypes by heterozygosity for dLMO. (A–C) Strong ectopic accumulation of Sens in a heterozygote of the gain-of-function allele Ly[1] (A, arrowheads) is not associated with ectopic cell death (B, arrowheads). (D–F) Heterozygosity for the null allele sens[E2] did not rescue the Cut or apoptosis defects of the mir-9a mutant. (G–I) Female heterozygote of the dLMO gain-of-function allele Bx[1] exhibits breaks in wing margin expression of Cut and ectopic apoptosis, similar to mir-9a mutant discs (compare with Fig. 2G, I). (J–L) Female heterozygosity for the null allele dLMO[hdpR26] rescued continuity of Cut expression at the wing margin and strongly suppressed ectopic apoptosis caused by loss of mir-9a.

Invertebrate and vertebrate Senseless proteins exhibit anti-apoptotic activity (Jafar-Nejad and Bellen, 2004), and Drosophila Sens specifically inhibits apoptosis by repressing pro-apoptotic genes such as reaper (Chandrasekaran and Beckendorf, 2003). We verified this by misexpressing Sens in the wing pouch, which yielded hundreds of ectopic sensory organ precursors, but not aberrant apoptosis (data not shown). Finally, mir-9a mutant wing discs that were heterozygous for sens still exhibited abundant apoptosis (Fig. 3D–F). Together, these observations suggested that the derepression of other targets might mediate the apoptotic phenotype of mir-9a mutants.

Amongst the many other predicted conserved targets of miR-9a is the transcriptional regulator encoded by Drosophila LIM-only (dLMO) (e.g http://www.targetscan.org/fly_12/). dLMO can sequester Chip, a LIM-domain cofactor of the LIM-homeodomain factor Apterous, which together specify the dorsal-ventral axis of the developing wing (Milan and Cohen, 2000). Excess dLMO activity, as seen in Beadex (Bx) alleles, titrates Chip protein and consequently interferes with wing margin development (Milán et al., 1998; Shoresh et al., 1998; Zeng et al., 1998). As is the case with mir-9a loss-of-function mutants, the development of the posterior wing margin is more sensitive than the anterior wing margin to increased dLMO (Fig. 1G, H), and Bx gain-of-function mutants of dLMO exhibit apoptosis in the developing wing pouch (Fristrom, 1969). We confirmed that Bx[1] heterozygous discs (i.e. female larvae, selected on the basis of gondal morphology to distinguish them from Bx[1]/Y hemizygous male larvae) exhibit excess apoptosis and breaks in wing margin Cut expression (Fig. 3G–I), similar to mir-9a mutants (Fig. 2G, I). These genetic observations raised dLMO as an attractive candidate target of miR-9a.

In wildtype, dLMO is expressed throughout the wing pouch but is elevated in the dorsal compartment (Fig. 2E). In contrast to Sens, dLMO protein was upregulated in mir-9a mutant wing pouches (Fig. 2J). The mutant tissue exhibited uniform dLMO across the dorsal and ventral compartment, indicating greater elevation of dLMO in the ventral compartment of mir-9a mutant discs. However, analysis of mir-9a mutant clones, which provide an internal control for accumulation of dLMO in neighboring non-clonal tissue, demonstrated a cell-autonomous increase in dLMO in both compartments (Fig. 2N–P).

We next tested whether dLMO exhibited genetic interactions with mir-9a. Impressively, loss of a single allele of dLMO (hdp[R26]) in females fully rescued the adult wing margin defect of both mir-9a[J22] homozygotes as well as mir-9a[J22]/[E39] transheterozygotes (Fig. 1J and data not shown). A similar genetic interaction was recently reported by Heitzler and colleagues (Biryukova et al., 2009). Heterozygosity of dLMO also strongly suppressed the apoptotic defect in the third instar wing pouch, and restored nearly normal expression of Wg, Cut (compare Fig. 2G, I to Fig. 3J–L) and Sens (data not shown) along the wing margin. Altogether, these observations indicate that repression of dLMO by miR-9a is critical to prevent apoptosis in the developing wing primordium.

dLMO is directly targeted by miR-9a

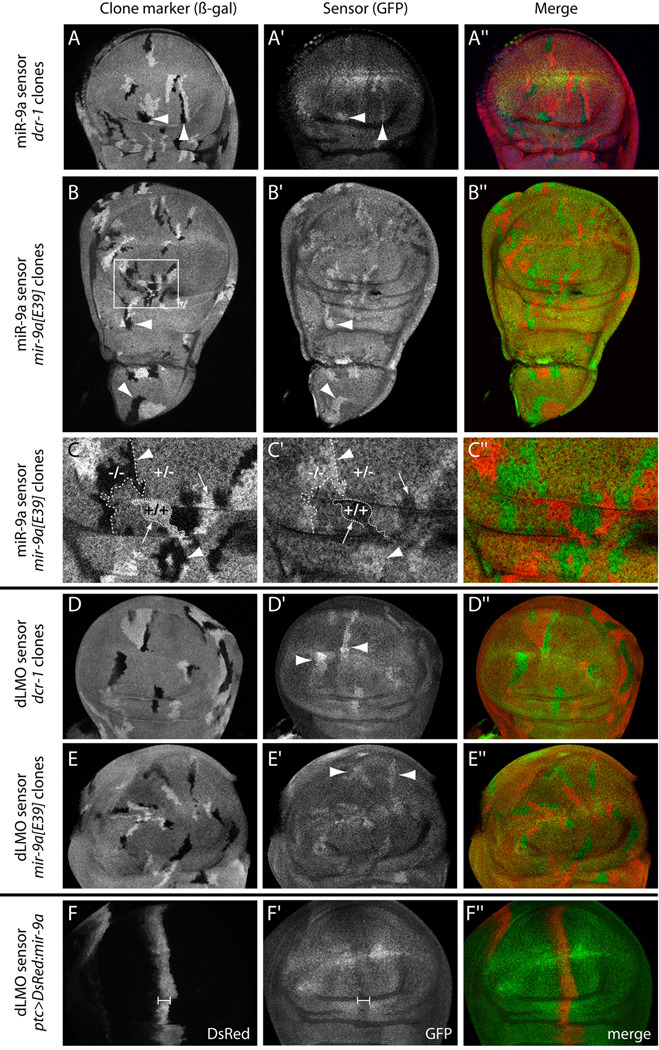

In principle, the effects of mir-9a loss-of-function on dLMO could be indirect. However, the dLMO 3' UTR contains an 8mer site for miR-9a (ACCAAAGA) in its 3’ UTR that is deeply conserved across the sequenced Drosophilid species (Biryukova et al., 2009), along with a nearby poorly-conserved G:U seed site (Supplementary Fig. 2). As well, loss of the dLMO 3' UTR is highly correlated with dLMO gain-of-function phenotypes (Biryukova et al., 2009; Shoresh et al., 1998). To assess the direct response of dLMO to miR-9a in vivo, we generated transgenic miR-9a and dLMO 3' UTR sensors fused to ubiquitously expressed GFP. We analyzed the behavior of these sensors in wing disc clones lacking the miRNA biogenesis enzyme Dicer-1 (Dcr-1), as well as clones specifically lacking miR-9a.

We first observed that the miR-9a sensor was upregulated in dcr-1 clones (Fig. 4A–A"), indicating that it is repressed by miRNAs in the wing disc. This sensor was specifically repressed by miR-9a, since mir-9a[E39] clones also upregulated the sensor (Fig. 4B–B"). Detailed examination revealed the exquisite sensitivity of the sensor to the endogenous level of the miRNA. We observed a perfectly inverse relationship of endogenous miR-9a dosage and miR-9a sensor activity: homozygous mir-9a mutant cells expressed the highest levels of the sensor, their twinspot wildtype clones displayed the lowest levels of the sensor, and mir-9a heterozygous cells exhibited an intermediate sensor level (Fig. 4C–C").

Figure 4.

dLMO is a direct in vivo target of miR-9a in the Drosophila wing disc. (A–A") hs-FLP; tub-GFP-mir-9a/+; FRT82B, dcr-1[Q1147x]/FRT82B, arm-lacZ disc carrying somatic clones marked by the absence of β-galactosidase (arrowheads). dcr-1 homozygous mutant cells exhibit elevated levels of the miR-9a GFP sensor. (B–B") hs-FLP; tub-GFP-mir-9a/+; mir-9a[E39], FRT80B/arm-lacZ, FRT80B disc bearing β-gal-negative clones (arrowheads). mir-9a homozygous mutant cells exhibit increased levels of the miR-9a GFP sensor throughout the wing disc, in both the wing pouch and the presumptive notum. (C–C") Magnification of the region boxed in (B) highlights the sensitivity of the miR-9a sensor to mir-9a dosage. Homozygous mutant cells (−/−) exhibit highest sensor activity while homozygous wildtype twinspots (+/+) exhibit lowest sensor activity; the remaining heterozygous (+/−) cells express an intermediate level of miR-9a sensor. (D–D") hs-FLP; tub-GFP-dLMO 3' UTR/+, FRT82B, dcr-1[Q1147x]/FRT82B, arm-lacZ disc; dLMO sensor is upregulated in dcr-1 mutant cells. (E–E") hs-FLP; tub-GFP-dLMO 3'UTR/+; mir-9a[E39], FRT80B/arm-lacZ, FRT80B disc; dLMO sensor is upregulated in mir-9a mutant cells. (F–F") ptc-Gal4, tub-GFP-dLMO 3' UTR; UAS-DsRed-mir-9a disc; the dLMO sensor is suppressed in the domain of ectopic miR-9a (bracket).

We next tested whether the dLMO sensor behaved similarly. Indeed, it was de-repressed in both dcr-1 clones (Fig. 4D–D") and mir-9a clones (Fig. 4E–E"), demonstrating that miR-9a directly represses dLMO via its 3' UTR in vivo. Finally, we performed reciprocal gain-of-function assays to examine the expression of the dLMO sensor in wing discs ectopically expressing UAS-DsRed-miR-9a under control of ptc-Gal4. We observed mild suppression of GFP-dLMO in the ptc-Gal4 domain (Fig. 4F–F"). Together with the phenotypic data, these in vivo sensor assays demonstrate that dLMO is the key direct target of endogenous miR-9a whose repression prevents apoptosis during Drosophila wing development.

Both sens and dLMO contribute to sensory organ defects in mir-9a mutants

Recently, dLMO was shown to act as a neural pre-patterning factor, working in concert with Pannier and Chip to promote the expression of proneural bHLH genes in dorsocentral (DC) proneural clusters (Asmar et al., 2008). In this capacity, it functions well upstream of sens, which is expressed in sensory organ precursor cells only following their Notch-mediated selection from proneural clusters. We therefore wondered whether deregulation of dLMO contributed to the development of ectopic sensory organs in mir-9a mutants.

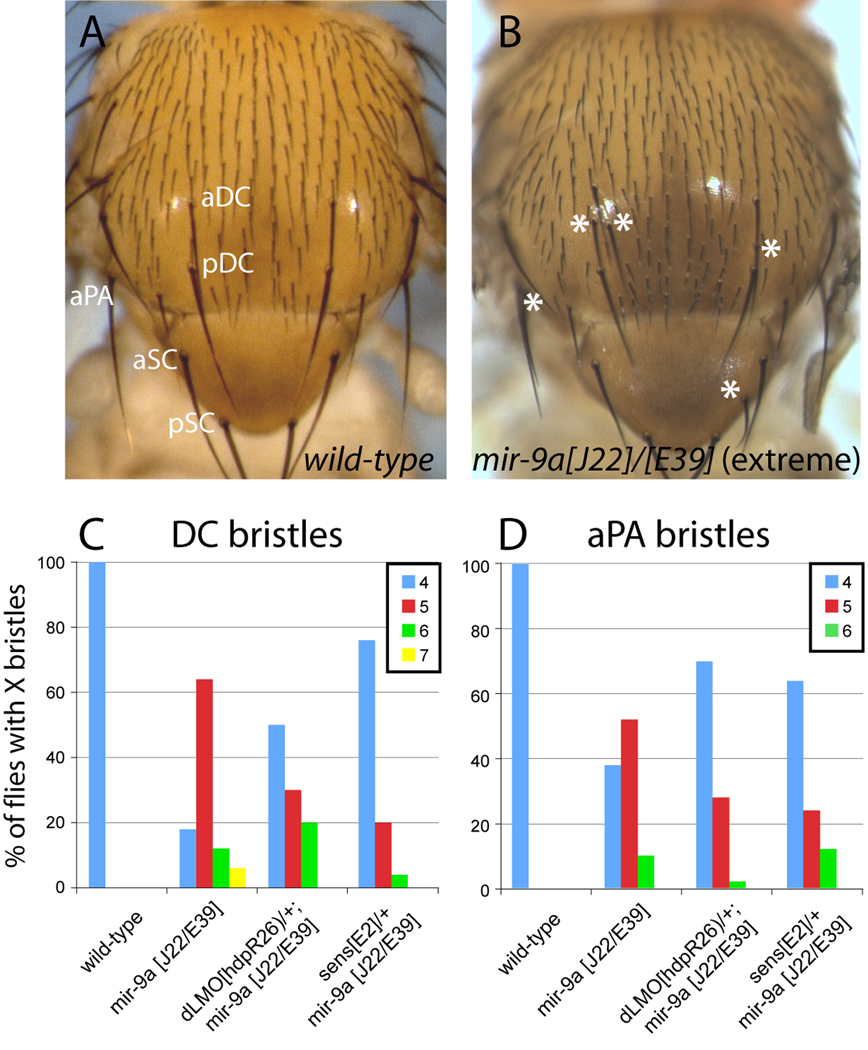

We first re-evaluated adult sensory organ phenotypes of mir-9a mutants in detail. As reported earlier, mir-9a mutants displayed increased density of stout mechanosensory bristles along the anterior wing margin and a mild increase in anterior scutellar (aSC) bristle organs (Li et al., 2006). However in our cultures, the aSC phenotype was not consistent across the three mir-9a null genotypes (n=50 females for each test, data not shown). Since laboratory stocks such as w[1118] are prone to exhibiting ectopic aSC bristles, miR-9a may not be the sole determinant for the aSC phenotype. We also observed a mild increase in notum microchaete density in mir-9a[J22] homozygotes and mir-9a[J22]/[E39] trans-heterozygotes, but not mir-9a[E39] homozygotes. Such variability of phenotypes in the various mir-9a genotypes is consistent with the notion that miR-9a functions as a neural "robustness" factor (Li et al., 2006), and that variation in genetic background may influence the penetrance of mild miR-9a-dependent phenotypes. We did, however, reproducibly observe some ectopic dorsocentral DC and anterior postalar (aPA) macrochaete bristles in all three genotypes, which we interpreted to be directly caused by miR-9a loss (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Contribution of dLMO and Sens to ectopic neurogenesis in mir-9a mutants. (A) Notum of a wild-type animal shows an orderly array of microchaete sensory organ bristles and precise positioning of the larger macrochaete bristles; aDC and pDC: anterior and posterior dorsocentrals; aSC and pSC: anterior and posterior scutellars; aPA: anterior postalar bristle. (B) Notum of mir-9a[J22]/[E39] mutant exhibits slightly increased density of microchaete bristles and ectopic DC, aSC and aPA bristles. Note that an extreme phenotype is shown for illustration purposes; many mir-9a mutant animals exhibit no ectopic macrochaetes or only a single extra bristle across all positions. (C) Heterozygosity for sens substantially suppresses the ectopic DC phenotype of mir-9a mutants. (D) Heterozygosity for either dLMO or sens partially suppressed the ectopic aPA phenotype of mir-9a mutants. Bristle counts were performed for 50 females in each genotype.

To minimize confounding background effects, we focused subsequent genetic modifier tests on the DC and aPA positions in mir-9a deletion trans-heterozygotes. We observed that sens heterozygosity could partially suppress ectopic neurogenesis at both DC and aPA positions (Fig. 5C, D). dLMO heterozygosity could partially suppress ectopic aPA macrochaetes, but had only mild effects at the DC position (Fig. 5C, D). Therefore, de-repression of dLMO and Sens are both relevant to the wing margin and the neurogenesis defects of mir-9a mutants, placing them amongst the most vital targets of miR-9a. At the same time, the phenotypic importance of these miR-9a:target interactions in different settings is distinct: repression of dLMO is more critical for wing development (since dLMO heterozygosity provided much better rescue of wing apoptosis and margin development), while restriction of Sens is more critical for bristle patterning (since sens heterozygosity provided much better rescue at the DC position).

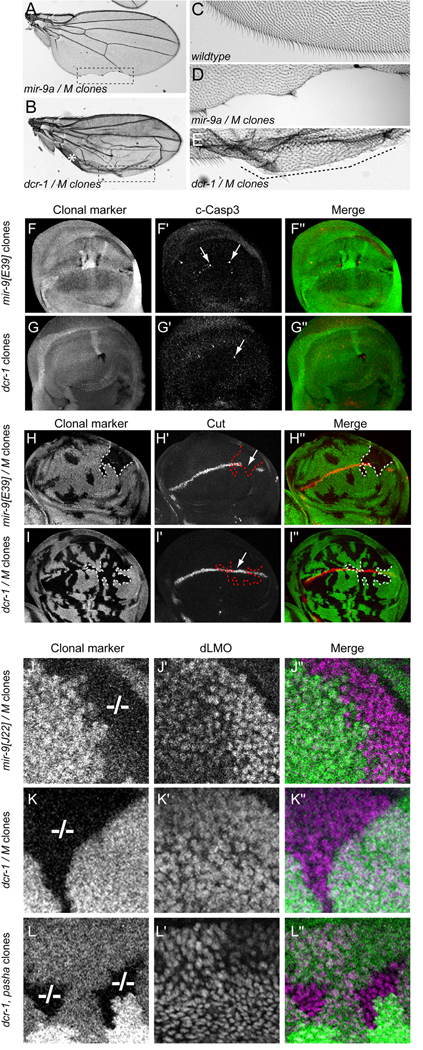

dcr-1 and pasha clones do not phenocopy mir-9a mutant clones

Since the detailed biology of few miRNA genes is presently known, many researchers examine conditional knockouts of miRNA biogenesis factors to assess the plausibility of miRNA-mediated control in a given setting. We were curious to see if the defects of mir-9a mutants were indeed recapitulated by clonal loss of dcr-1 (Lee et al., 2004), which is required for the biogenesis of all Drosophila miRNAs. Adult wings carrying mir-9a[E39] clones exhibited notching along the posterior wing margin (Fig. 6A, D), similar to homozygous mutant wings (Fig. 1B). On the other hand, wings carrying dcr-1 clones were not flat and exhibited blistering, likely due in part to uneven growth of the wing surfaces caused by the lack of growth-promoting miRNAs such as bantam in dcr-1 mutant cells (Fig. 6B) (Brennecke et al., 2003; Friggi-Grelin et al., 2008; Martin et al., 2009). Surprisingly, we did not observe the tissue loss typical of wings bearing mir-9a clones amongst >100 wings carrying high frequency dcr-1 clones generated with either vg-FLP, ubx-FLP, or hs-FLP, even though large sectors of mutant wing margin tissue exhibiting defective non-sensory bristle differentiation were commonly evident (Fig. 6B, E and data not shown). To test this further, we analyzed clones of pasha (Martin et al., 2009), which encodes an obligate nuclear cofactor for the primary miRNA processing factor Drosha. Again, the presence of these mutant clones caused abnormal wing growth, but they always exhibited continuous wing margin (data not shown).

Figure 6.

dcr-1 and pasha clones do not phenocopy mir-9a clones. (A) Wing carrying large mir-9a[E39] clones induced with hs-FLP and the Minute technique exhibit notching along the posterior wing margin. (B) Wing carrying large dcr-1[Q1147x] mutant clones induced with hs-FLP and the Minute technique. The uneven surface of the wing prevented a flat mounting, and the asterisk indicates a section of the wing that folded over on itself. Nevertheless, no loss of margin tissue was observed. (C) Closeup of the wildtype posterior wing margin highlights a regular array of non-sensory bristles. (D) Magnification of the posterior wing margin in panel A (boxed region) illustrates substantial loss of tissue in wing bearing mir-9a clones. (E) Magnification of the posterior margin of the wing bearing dcr-1 clones in panel B (boxed region); the differentiation of posterior wing margin bristles is highly disturbed (dotted line), but the margin remained continuous. (F–L) Clonal analysis of wing pouch development. Mutant clones are marked by their absence of β-gal or GFP in the "clonal marker" channel; antigens of interest are shown in F'–L', and merged images are shown in F"–L". Panels F, G, I, K and L depict lacZ clonal markers while panels H and J used GFP markers; the choice of marker did not affect the results. The Minute technique ("M" genotype) was used in panels H, I, J and K. (F–G) Staining for cleaved caspase-3 in mir-9a and dcr-1 clones showed that both exhibit apoptotic cells. (H–I) mir-9a/M clones that overlap the middle region of the posterior wing margin reliably showed a break in Cut expression (H', arrow), whereas similarly positioned dcr-1/M clones frequently maintained Cut expression (I', arrow). (J–L) dLMO staining of ventral wing pouch clones of mir-9, dcr-1 and pasha mutant alleles; these are shown at higher magnification than panels F–I. Homozygous mutant clones are indicated by "−/− ". (J) mir-9a[E39]/M clones reliably exhibit strong upregulation of dLMO in the ventral wing pouch. (K) dcr-1[Q1147x]/M ventral wing clones do not upregulate dLMO. (L) dcr-1[Q1147x], pasha[KO] double mutant ventral clones express normal levels of dLMO.

We next asked if phenotypic differences between the different mutant clones were apparent at the third instar. We observed that small mir-9a[E39] clones contained apoptotic cells (Fig. 6F–F"), consistent with the whole disc mir-9a mutants. We observed that similarly-sized dcr-1 clones also preferentially contained apoptotic cells (Fig. 6G–G"). Because of the growth defect of Dcr-1 clones, we sensitized this assay by generating large clones using the Minute technique. Mutant clones of both mir-9a and Dcr-1 in this background exhibited high incidence of reactivity with cleaved Caspase-3, but there was also substantial non-autonomous apoptosis (data not shown), likely due to cell competition induced in the Minute background (Morata and Ripoll, 1975; Tyler et al., 2007). In any case, the excess apoptosis in dcr-1 mutant disc clones was consistent with the apoptotic phenotype of conditional knockout of mammalian Dicer in various organs (Damiani et al., 2008; De Pietri Tonelli et al., 2008; Harfe et al., 2005; Schaefer et al., 2007). In addition to loss of miR-9a, it is certainly conceivable that loss of other miRNAs contributes to the apoptotic defect of dcr-1 clones.

However, when we examined the expression of Cut at the wing margin, we observed a clear difference between mir-9a and dcr-1 clones. mir-9a[E39] clones that overlapped the central region of the posterior wing margin reliably exhibited loss of Cut (Fig. 6H–H" and Supplemental Figure 3A), consistent with the results from mir-9a mutant discs (Fig. 2G). Note that Cut was not necessarily lost throughout the clone, as expected from the fact that whole mir-9a mutant discs typically lost only a portion of Cut at the posterior wing margin (Fig. 2G). In contrast, similarly-positioned dcr-1 clones frequently maintained Cut (Fig. 6I–I"). We noted examples of wing pouches bearing posterior dcr-1 clones that exhibited a decrease or loss of Cut (Supplemental Figure 3B, C). However, such loss was not particularly associated with the clone boundary, and often extended into the wild-type tissue. The basis of this variable phenotype is not clear, but conceivably may be a consequence of the altered growth properties of dcr-1 mutant cells, leading to uncoordinated wing margin development. In any case, we could clearly distinguish that mir-9a mutant clones that overlapped the central region of the posterior wing margin consistently lacked Cut, whereas dcr-1 mutant clones did not.

We next studied the expression of dLMO, which we showed to be a key direct target that is de-repressed in mir-9a mutant wings. We focused here on dLMO in the ventral compartment of the wing pouch, since its elevation in mir-9a mutant cells was especially evident in ventral clones (Fig. 2N–P and Fig. 6J–J"). Surprisingly, we did not observe comparable increases in dLMO staining in dcr-1 mutant clones (Fig. 6K–K"). We sensitized this further by generating dcr-1, pasha double mutant clones, but these still did not exhibit the defect in dLMO accumulation (Fig. 6L–L") seen in wing disc cells lacking only miR-9a.

These results indicated that loss of miR-9a was more dentrimental to normal expression of Cut and dLMO in the wing pouch than was loss of Dcr-1 and/or Pasha, consistent with the observation that mir-9a but not dcr-1 or pasha mutant cells reliably exhibit loss of adult wing tissue. These data are perhaps especially unexpected given that cells that are mutant for miRNA biogenesis factors clearly de-repress both miR-9a and dLMO sensors (Fig. 4), and are thus are demonstrably deficient in miR-9a activity (along with most if not all other miRNAs). We conclude that the failure to observe certain mutant phenotypes upon conditional knockout of core miRNA biogenesis factors does not rule out critical roles for miRNAs in a given setting.

Conclusions

dLMO is an essential genetic switch target of Drosophila miR-9a

Because of their relative ease of detection, dominant alleles and X-linked mutants constituted a high proportion of the classical spontaneous mutants isolated by Morgan and colleagues. Bridges isolated Bx[1] in 1923 (Morgan, 1925), and genetic tests by Green in the early 1950s established that Bx was due to overactivity of the locus (Green, 1952). In fact, the recessive allele Bx[r] was associated with a duplication of the region, indicating that as little as a two-fold increase in Bx activity could interfere with wing development. In 1979, Lifschytz and Green further proposed that Bx might be due to a mutation in a cis-acting repressor site in the heldup locus (Lifschytz and Green, 1979). Indeed, the cloning of Bx by the Cohen, Jan, and Segal labs in 1998 finally revealed that Bx and heldup were gain- and loss-of-function alleles of the dLMO gene, respectively (Milán et al., 1998; Shoresh et al., 1998; Zeng et al., 1998). Moreover, most spontaneous Bx alleles proved to be transposable element insertions in the dLMO 3’ UTR, and new Bx mutants were easily obtained by imprecise excisions of a downstream transposable element, so as to delete dLMO 3’ UTR sequence (Shoresh et al., 1998). Collectively, these 85 years of research indicated that 3'UTR-mediated post-transcriptional repression of dLMO is critical for normal development.

A small number of other gain-of-function mutants in Drosophila and C. elegans result from the loss of 3’ UTR regulatory elements, and many of these are now appreciated to be key genetic switch targets of miRNAs (Flynt and Lai, 2008). Our studies, together with concurrent work from Heitzler and colleagues (Biryukova et al., 2009), establish dLMO as one of a handful of genes whose loss of miRNA-mediated repression leads to a severe morphological defect. We found that the lack of mir-9a results in upregulation of dLMO, aberrant apoptosis in the wing pouch, and failure to completely specify and develop the wing margin. Importantly, dorsal-specific expression of miR-9a, dorsal-specific inhibition of cell death (using p35 or Diap1), or heterozygosity for dLMO, all strongly reduced ectopic apoptosis and restored adult wing development in mir-9a null animals.

Ectopic apoptosis in the wing pouch has previously been reported to result in loss of wing margin (Delanoue et al., 2004; Smith-Bolton et al., 2009; Sotillos and Campuzano, 2000; Yoshida et al., 2001). However in other cases, the disc is able to compensate for cell loss in the face of ectopic apoptosis, so that no loss of margin is observed in the adult wing (Cifuentes and Garcia-Bellido, 1997; Ng et al., 1995; Perez-Garijo et al., 2004). In the mir-9a mutant, we show that excess apoptosis is coupled with a margin specification defect. Despite our ability to rescue the mutant by inhibiting apoptosis, we do not rule out that ectopic apoptosis by itself might be insufficient to induce adult margin loss; perhaps it requires the sensitized background evidenced by the demonstrable failure to fully activate Cut in the third instar. We also note that Bx was recently reported not to be suppressed by inhibiting apoptosis (Bejarano et al., 2008), which might be at odds with our conclusions. However, that study examined Bx/Y hemizygotes, which are substantially stronger in phenotype than Bx/X heterozygotes. It is clear that elevation of dLMO yields a variety of patterning defects that are not seen in mir-9a mutants (Milán et al., 1998; Zeng et al., 1998). We infer that loss of miR-9a results in apoptosis and wing margin defects that are attributable to de-repression of dLMO, but that elevation of dLMO can clearly generate developmental phenotypes that are not simply due to excess apoptosis.

A minor, but quantifiable, consequence of lacking mir-9a is the development of a small number of ectopic sensory organs. This is demonstrably due to the de-repression of the proneural factors Sens and dLMO. Therefore, even though computational approaches provide evidence for hundreds of conserved miR-9a targets, including compelling "anti-target" relationships with a large number of neural genes (Stark et al., 2005), the bulk of its morphologically evident phenotypes can be accounted for by the failure to repress only two target genes, sens and dLMO (Biryukova et al., 2009; Li et al., 2006). In addition to miR-9a, Drosophilid species encode miR-9b and miR-9c, as well as the ancestrally related miR-79 (Aravin et al., 2003; Lai et al., 2003; Lai et al., 2004). The function of these miRNAs remains to be studied, but conventional knowledge of miRNA targeting suggests that they may have overlapping target capacity since they have similar seeds. It is conceivable that the analysis of double or triple mir-9 mutants may reveal additional targets that mediate compelling phenotypes. Nevertheless, it is clear that miR-9a serves a function to repress dLMO and sens that cannot be substantially compensated by the remaining miR-9-related genes.

Implications for the regulation of human dLMO genes

dLMO and miR-9 are both highly conserved between invertebrates and vertebrates. However, vanishingly few miRNA:target interactions have been preserved over this evolutionary distance, indicating that these post-transcriptional target networks are much more plastic than the genes themselves (Chen and Rajewsky, 2006). Therefore, the existence of a key miR-9a:dLMO regulatory connection in flies does not necessary imply that human miR-9 regulates LMO genes, and human LMO genes lack conserved canonical miR-9 seed sites (http://www.targetscan.org/). Heitzler and colleagues proposed that mammalian LMO2 is a conserved target of miR-9 (Biryukova et al., 2009). However, the candidate site contains a G:U seedpair, a feature that is detrimental to, although not necessarily incompatible with miRNA targeting (Brennecke et al., 2005; Doench and Sharp, 2004; Lai et al., 2005). Directed studies are needed to assess whether this site alone confers repression by miR-9.

On the other hand, the necessity of restricting LMO activity might well prove to be a conserved feature of invertebrate and vertebrate biology. As in Drosophila, vertebrate LMO proteins can dominantly interfere with LDB:Islet complexes, indicating that its overactivity is especially "dangerous". Indeed, elevation of LMO proteins has myriad consequences for downstream transcriptional networks, and LMO2 is in fact a T-cell oncogene (Rabbitts, 1998). Intriguingly, LMO2, which normally regulates hematopoetic development (Warren et al., 1994), has a highly conserved 8mer seed for miR-223 (http://www.targetscan.org/). Recent studies demonstrated that mir-223 mutant mice exhibit hematopoetic defects, and that mir-223 deletion has consequences for the neutrophil transcriptome and proteome (Baek et al., 2008; Johnnidis et al., 2008). While the depth of peptide sampling was insufficient to report on LMO2 status, the microarray data demonstrated LMO2 to be the 60th most-upregulated mRNA across the transcriptome of mir-223 knockout cells. Indeed, Marziali and colleagues recently reported that suppression of LMO2 by miR-223 regulates erythropoiesis (Felli et al., 2009). We note that its paralog LMO1 contains a highly conserved canonical site for miR-181, another miRNA with a demonstrated function in the hematopoietic system (Chen et al., 2004). These observations suggest that the regulation of vertebrate LMO genes by hematopoietic miRNAs, and its potential relevance to cancer, deserves further study.

Implications for studying conditional loss of miRNA biogenesis factors

To date, relatively few Drosophila or vertebrate miRNA genes have been analyzed using bona fide mutant alleles (Smibert and Lai, 2008). As an approximation, many researchers have taken to analyzing the effects of conditional knockout of miRNA biogenesis factors, such as Dicer. This manipulation is presumed to break all miRNA regulatory links, thereby serving as a plausibility test of whether miRNAs might be required in a given setting. Acknowledged drawbacks of this approach include uncertainty as to whether one or many miRNAs might contribute to a given phenotype, and whether phenotypes are a direct or indirect cause of miRNA loss. However, a caveat that is little considered is the potentially canceling effects of removing "all" miRNAs, so that loss of one miRNA might be compensated for by the concomitant loss of another miRNA(s). While such an outcome might seem to require highly unlikely coincidences, it may be plausible if we consider that most biological processes are under both positive and negative control, and that most genes are themselves miRNA targets.

During development of the Drosophila wing primordium, we showed that clones lacking mir-9a upregulate dLMO and induce wing notching, whereas dcr-1 and pasha-mutant clones do not (Fig. 6). Additionally, mir-9a mutant clones exhibit a more severe phenotype than dcr-1 mutant clones with respect to loss of wing margin, both in the third instar wing pouch and in the adult wing. Although the cells analyzed were homozygous mutant for substantial periods of time (72–96 hours), perdurance of miRNAs on account of Dcr-1 or Pasha proteins inherited by mutant cells conceivably contributes to the phenotypic disparity. For example, perdurance may explain the incomplete phenocopy of bantam mutant discs by dcr-1 or pasha "whole disc" mutants (Brennecke et al., 2003; Martin et al., 2009). However, potential perdurance is not reconciled with the comparable upregulation of miR-9a and dLMO sensor activity in dcr-1 and mir-9a homozygous mutant cells (Fig. 4), which report on similar loss of miR-9a activity in these clones. Together, these data suggest that mir-9a mutant cells exhibit phenotypes that are intrinsically different from those of dcr-1 or pasha mutant cells.

In summary, the failure to observe a phenotype in cells or tissues that are mutant for a general miRNA biogenesis factor cannot reliably be taken as evidence that miRNAs lack substantial roles in the setting of interest. Reciprocally, our observation that loss of miRNA-mediated regulation from a single target gene (e.g. failure to repress dLMO in mir-9a mutant wings) can be of greater phenotypic impact than loss of "all" miRNA-mediated regulation (e.g, in dcr-1, pasha double mutant wing clones) highlights the disproportionate consequence of releasing particular miRNA targets from amidst a regulatory web that is inferred to encompass most animal transcripts.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Drs. Fen-Biao Gao, Hugo Bellen, Marco Milan, Richard Carthew, Konrad Basler, David Bilder, and Stephen Cohen for gracious gifts of Drosophila stocks and antibodies that were critical for this study. E.C.L. was supported by the Sidney Kimmel Cancer Foundation, the Alfred Bressler Scholars Fund and the US National Institutes of Health (R01-GM083300).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aravin A, Lagos-Quintana M, Yalcin A, Zavolan M, Marks D, Snyder B, Gaasterland T, Meyer J, Tuschl T. The small RNA profile during Drosophila melanogaster development. Dev. Cell. 2003;5:337–350. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00228-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asmar J, Biryukova I, Heitzler P. Drosophila dLMO-PA isoform acts as an early activator of achaete/scute proneural expression. Dev Biol. 2008;316:487–497. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baek D, Villen J, Shin C, Camargo FD, Gygi SP, Bartel DP. The impact of microRNAs on protein output. Nature. 2008;455:64–71. doi: 10.1038/nature07242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell. 2009;136:215–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bejarano F, Luque CM, Herranz H, Sorrosal G, Rafel N, Pham TT, Milan M. A gain-of-function suppressor screen for genes involved in dorsal-ventral boundary formation in the Drosophila wing. Genetics. 2008;178:307–323. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.081869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biryukova I, Asmar J, Abdesselem H, Heitzler P. Drosophila mir-9a regulates wing development via fine-tuning expression of the LIM only factor, dLMO. Dev Biol. 2009;327:487–496. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennecke J, Hipfner DR, Stark A, Russell RB, Cohen SM. bantam Encodes a developmentally regulated microRNA that controls cell proliferation and regulates the proapoptotic gene hid in Drosophila. Cell. 2003;113:25–36. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00231-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennecke J, Stark A, Russell RB, Cohen SM. Principles of MicroRNA-Target Recognition. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e85. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadigan KM. Regulating morphogen gradients in the Drosophila wing. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2002;13:83–90. doi: 10.1016/s1084-9521(02)00014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekaran V, Beckendorf SK. senseless is necessary for the survival of embryonic salivary glands in Drosophila. Development. 2003;130:4719–4728. doi: 10.1242/dev.00677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CZ, Li L, Lodish HF, Bartel DP. MicroRNAs modulate hematopoietic lineage differentiation. Science. 2004;303:83–86. doi: 10.1126/science.1091903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K, Rajewsky N. Deep conservation of microRNA-target relationships and 3'UTR motifs in vertebrates, flies, and nematodes. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2006;71:149–156. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2006.71.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cifuentes FJ, Garcia-Bellido A. Proximo-distal specification in the wing disc of Drosophila by the nubbin gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:11405–11410. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.21.11405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damiani D, Alexander JJ, O'Rourke JR, McManus M, Jadhav AP, Cepko CL, Hauswirth WW, Harfe BD, Strettoi E. Dicer inactivation leads to progressive functional and structural degeneration of the mouse retina. J Neurosci. 2008;28:4878–4887. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0828-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Pietri Tonelli D, Pulvers JN, Haffner C, Murchison EP, Hannon GJ, Huttner WB. miRNAs are essential for survival and differentiation of newborn neurons but not for expansion of neural progenitors during early neurogenesis in the mouse embryonic neocortex. Development. 2008;135:3911–3921. doi: 10.1242/dev.025080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delanoue R, Legent K, Godefroy N, Flagiello D, Dutriaux A, Vaudin P, Becker JL, Silber J. The Drosophila wing differentiation factor vestigial-scalloped is required for cell proliferation and cell survival at the dorso-ventral boundary of the wing imaginal disc. Cell Death Differ. 2004;11:110–122. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doench JG, Sharp PA. Specificity of microRNA target selection in translational repression. Genes Dev. 2004;18:504–511. doi: 10.1101/gad.1184404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felli N, Pedini F, Romania P, Biffoni M, Morsilli O, Castelli G, Santoro S, Chicarella S, Sorrentino A, Peschle C, Marziali G. MicroRNA 223-dependent expression of LMO2 regulates normal erythropoiesis. Haematologica. 2009;94:479–486. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2008.002345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynt AS, Lai EC. Biological principles of microRNA-mediated regulation: shared themes amid diversity. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9:831–842. doi: 10.1038/nrg2455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friggi-Grelin F, Lavenant-Staccini L, Therond P. Control of Antagonistic Components of the Hedgehog Signaling Pathway by microRNAs in Drosophila. Genetics. 2008;179:429–439. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.083733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fristrom D. Cellular degeneration in the production of some mutant phenotypes in Drosophila melanogaster. Mol Gen Genet. 1969;103:363–379. doi: 10.1007/BF00383486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green MM. The Beadex Locus in Drosophila Melanogaster: The Genotypic Constitution of Bx. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1952;38:949–953. doi: 10.1073/pnas.38.11.949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harfe BD, McManus MT, Mansfield JH, Hornstein E, Tabin CJ. The RNaseIII enzyme Dicer is required for morphogenesis but not patterning of the vertebrate limb. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:10898–10903. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504834102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jafar-Nejad H, Bellen HJ. Gfi/Pag-3/senseless zinc finger proteins: a unifying theme? Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:8803–8812. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.20.8803-8812.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnnidis JB, Harris MH, Wheeler RT, Stehling-Sun S, Lam MH, Kirak O, Brummelkamp TR, Fleming MD, Camargo FD. Regulation of progenitor cell proliferation and granulocyte function by microRNA-223. Nature. 2008 doi: 10.1038/nature06607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klämbt C, Knust E, Tietze K, Campos-Ortega J. Closely related transcripts encoded by the neurogenic gene complex Enhancer of split of Drosophila melanogaster. EMBO J. 1989;8:203–210. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb03365.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai EC. microRNAs are complementary to 3' UTR sequence motifs that mediate negative post-transcriptional regulation. Nat Genet. 2002;30:363–364. doi: 10.1038/ng865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai EC, Burks C, Posakony JW. The K box, a conserved 3' UTR sequence motif, negatively regulates accumulation of Enhancer of split Complex transcripts. Development. 1998;125:4077–4088. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.20.4077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai EC, Posakony JW. The Bearded box, a novel 3' UTR sequence motif, mediates negative post-transcriptional regulation of Bearded and Enhancer of split Complex gene expression. Development. 1997;124:4847–4856. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.23.4847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai EC, Rubin GM. neuralized functions cell-autonomously to regulate a subset of Notch-dependent processes during adult Drosophila development. Dev Biol. 2001;231:217–233. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.0124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai EC, Tam B, Rubin GM. Pervasive regulation of Drosophila Notch target genes by GY-box-, Brd-box-, and K-box-class microRNAs. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1067–1080. doi: 10.1101/gad.1291905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai EC, Tomancak P, Williams RW, Rubin GM. Computational identification of Drosophila microRNA genes. Genome Biol. 2003;4:R42.1–R42.20. doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-4-7-r42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai EC, Wiel C, Rubin GM. Complementary miRNA pairs suggest a regulatory role for miRNA:miRNA duplexes. RNA. 2004;10:171–175. doi: 10.1261/rna.5191904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee RC, Feinbaum RL, Ambros V. The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell. 1993;75:843–854. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90529-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YS, Nakahara K, Pham JW, Kim K, He Z, Sontheimer EJ, Carthew RW. Distinct Roles for Drosophila Dicer-1 and Dicer-2 in the siRNA/miRNA Silencing Pathways. Cell. 2004;117:69–81. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00261-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leviten MW, Lai EC, Posakony JW. The Drosophila gene Bearded encodes a novel small protein and shares 3' UTR sequence motifs with multiple Enhancer of split Complex genes. Development. 1997;124:4039–4051. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.20.4039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leviten MW, Posakony JW. Gain-of-function alleles of Bearded interfere with alternative cell fate decisions in Drosophila adult sensory organ development. Dev. Biol. 1996;176:264–283. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Wang F, Lee JA, Gao FB. MicroRNA-9a ensures the precise specification of sensory organ precursors in Drosophila. Genes & Development. 2006;20:2793–2805. doi: 10.1101/gad.1466306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lifschytz E, Green MM. Genetic identification of dominant overproducing mutations: the Beadex gene. Mol Gen Genet. 1979;171:153–159. doi: 10.1007/BF00270001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin R, Smibert P, Yalcin A, Tyler DM, Schaefer U, Tuschl T, Lai EC. A Drosophila pasha mutant distinguishes the canonical miRNA and mirtron pathways. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:861–870. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01524-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milan M, Cohen SM. Temporal regulation of apterous activity during development of the Drosophila wing. Development. 2000;127:3069–3078. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.14.3069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milán M, Diaz-Benjumea FJ, Cohen SM. Beadex encodes an LMO protein that regulates Apterous LIM-homeodomain activity in Drosophila wing development: a model for LMO oncogene function. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2912–2920. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.18.2912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr OL. Contribution to the X-chromosome map in Drosophila melanogaster. Nyt Mag Naturv. 1927;65:265–274. [Google Scholar]

- Morata G, Ripoll P. Minutes: mutants of drosophila autonomously affecting cell division rate. Dev Biol. 1975;42:211–221. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(75)90330-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan T. The genetics of Drosophila melanogaster. Biblphia Genet. 1925;2 [Google Scholar]

- Ng M, Diaz-Benjumea FJ, Cohen SM. Nubbin encodes a POU-domain protein required for proximal-distal patterning in the Drosophila wing. Development. 1995;121:589–599. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.2.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolo R, Abbott L, Bellen HJ. Senseless, a Zn finger transcription factor, is necessary and sufficient for sensory organ development in Drosophila. Cell. 2000;102:349–362. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00040-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolo R, Abbott L, Bellen HJ. Drosophila Lyra mutations are gain-of-function mutations of senseless. Genetics. 2001;157:307–315. doi: 10.1093/genetics/157.1.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Garijo A, Martin FA, Morata G. Caspase inhibition during apoptosis causes abnormal signalling and developmental aberrations in Drosophila. Development. 2004;131:5591–5598. doi: 10.1242/dev.01432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabbitts TH. LMO T-cell translocation oncogenes typify genes activated by chromosomal translocations that alter transcription and developmental processes. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2651–2657. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.17.2651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer A, O'Carroll D, Tan CL, Hillman D, Sugimori M, Llinas R, Greengard P. Cerebellar neurodegeneration in the absence of microRNAs. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1553–1558. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoresh M, Orgad S, Shmueli O, Werczberger R, Gelbaum D, Abiri S, Segal D. Overexpression Beadex mutations and loss-of-function heldup-a mutations in Drosophila affect the 3' regulatory and coding components, respectively, of the dLMO gene. Genetics. 1998;150:283–299. doi: 10.1093/genetics/150.1.283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smibert P, Lai EC. Lessons from microRNA mutants in worms, flies and mice. Cell Cycle. 2008;7 doi: 10.4161/cc.7.16.6454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith-Bolton RK, Worley MI, Kanda H, Hariharan IK. Regenerative growth in Drosophila imaginal discs is regulated by Wingless and Myc. Dev Cell. 2009;16:797–809. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sotillos S, Campuzano S. DRacGAP, a novel Drosophila gene, inhibits EGFR/Ras signalling in the developing imaginal wing disc. Development. 2000;127:5427–5438. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.24.5427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark A, Brennecke J, Bushati N, Russell RB, Cohen SM. Animal MicroRNAs confer robustness to gene expression and have a significant impact on 3'UTR evolution. Cell. 2005;123:1133–1146. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark A, Brennecke J, Russell RB, Cohen SM. Identification of Drosophila MicroRNA Targets. PLoS Biol. 2003;1:E60. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0000060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler DM, Li W, Zhuo N, Pellock B, Baker NE. Genes affecting cell competition in Drosophila. Genetics. 2007;175:643–657. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.061929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren AJ, Colledge WH, Carlton MB, Evans MJ, Smith AJ, Rabbitts TH. The oncogenic cysteine-rich LIM domain protein rbtn2 is essential for erythroid development. Cell. 1994;78:45–57. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90571-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wightman B, Burglin TR, Gatto J, Arasu P, Ruvkun G. Negative regulatory sequences in the lin-14 3'-untranslated region are necessary to generate a temporal switch during Caenorhabditis elegans development. Genes Dev. 1991;5:1813–1824. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.10.1813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wightman B, Ha I, Ruvkun G. Posttranscriptional regulation of the heterochronic gene lin-14 by lin-4 mediates temporal pattern formation in C. elegans. Cell. 1993;75:855–862. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90530-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida H, Inoue YH, Hirose F, Sakaguchi K, Matsukage A, Yamaguchi M. Over-expression of DREF in the Drosophila wing imaginal disc induces apoptosis and a notching wing phenotype. Genes Cells. 2001;6:877–886. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2001.00473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng C, Justice NJ, Abdelilah S, Chan Y-M, Jan LY, Jan YN. The Drosophila LIM-only gene, dLMO, is mutated in Beadex alleles and might represent an evolutionarily conserved function in appendage development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:10637–10642. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.