Abstract

That changes in membrane lipid composition alter the barrier function of tight junctions illustrates the importance of the interactions between tetraspan integral tight junction proteins and lipids of the plasma membrane. Application of methyl-β-cyclodextrin to both apical and basolateral surfaces of MDCK cell monolayers for 2 hours, results in an ~80% decrease in cell cholesterol, a fall in transepithelial electrical resistance and a 30% reduction in cell content of occludin, with a smaller reduction in levels of claudins -2, -3 and -7. There were negligible changes in levels of actin, and the two non-tight junction membrane proteins GP-135 and caveolin-1. While in untreated control cells breakdown of occludin, and probably other tight junction proteins, is mediated by intracellular proteolysis, our current data suggest an alternative pathway whereby in a cholesterol-depleted membrane, levels of tight junction proteins are decreased via direct release into the intercellular space as components of membrane-bounded particles. Occludin, along with two of its degradation products and several claudins, increases in the basolateral medium after incubation with methyl-β-cyclodextrin for 30 minutes In contrast caveolin-1 is detected only in the apical medium after adding methyl-β-cyclodextrin. Release of occludin and its proteolytic fragments continues even after removal of methyl-β-cyclodextrin. Sedimentation and ultrastructural studies indicate that the extracellular tight junction proteins are associated with the membrane bounded particles that accumulate between adjacent cells. Disruption of the actin filament network by cytochalasin D, did not diminish methyl-β-cyclodextrin-induced release of tight junction proteins into the medium, suggesting that the mechanism underlying their formation is not actin-dependent. The 41 and 48 kDa C-terminal occludin fragments formed during cholesterol depletion result from the action of a GM6001-sensitive metalloproteinase(s) at some point in the path leading to release of the membrane particles.

INTRODUCTION

Epithelial cell monolayers form functionally and biochemically polarized barriers separating distinct tissue compartments. The biochemical polarity in cells is established by intracellular sorting and polarized delivery mechanisms and is maintained, in part, by tight junctions. Membrane proteins and lipids are both distributed in a polarized fashion between apical (AP) and basolateral (BL) membrane domains [1]. Recent studies of the post-translational lipid modification of tight junction (TJ) proteins [2, 3], and the significant effects of experimentally altered membrane lipid composition on TJ physiology [2, 4–7], underscore the importance of lipid/protein interactions in the barrier function of TJs.

Integral tight junction proteins, occludin [8], claudins [9] and tricellulin [10] have in common a tetraspan conformation, with their four transmembrane domains being in intimate contact with plasma membrane lipids. In previous studies it was shown that within 30–60 minutes of adding methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MβCD) to the culture medium, there was a decrease in cholesterol (CH) levels by approximately 60% that was associated with a rise in transepithelial electrical resistance (TER) by 40% and an increase in the phosphorylation of occludin [2, 7]. Extending the incubation beyond that time, results in a steady decline in TER. Despite the steep fall in CH levels during a two h incubation with MβCD, the cultures remain 95% viable, as assessed by the release of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) from the cells; there was no evidence of apoptosis [7]. Furthermore, upon removal of MβCD for 20 h, TER recovered to values that were equal to or greater than those of control cultures. The MβCD-induced decline in TJ barrier function was accompanied by a number of morphological alterations in the cell monolayer; among them an aggregation of actin in the tri-cellular regions of the TJ, a reduction in the number of apical microvilli and an accumulation of round, membrane bounded particles in the intercellular space that was not evident in control cultures [7]. Western blot analysis of CH-depleted-monolayers revealed a decline in the cellular levels of occludin and selected claudins and an increase in lower MW occludin C-terminal fragments [2]. These observations together with others published data [2, 11] showing that TJ proteins are components of CH rich lipid microdomains, suggested the possibility that, in addition to intracellular routes for metabolism of TJ proteins [12], a reduction in membrane CH might alter lipid microdomain composition in a manner that causes release of membrane vesicles, enriched for TJ proteins, into the BL space. That TJ-enriched blebs might be released directly into the extracellular space was first suggested in a freeze-fracture study using HT29 cells which, under conditions favoring TJ disassembly, formed discrete patches on the plasma membrane containing remnants of the TJ fibrils [13] Shedding of other cell surface proteins following CH depletion has been reported for a lymphoma derived cell line and COS-7 cells [14, 15].

Given these observations and the increasing interest in the role of microvesicles in cell biology [16], we have, in the present study, examined the possibility that the vesicle-like particles that accumulate between the BL surfaces of CH depleted MDCK cells are enriched for TJ proteins. Our results indicate that such is the case and that these particles are especially enriched for c-terminal fragments of occludin formed by the action of metalloproteinase(s) activated in CH depleted cells. Based on their size, ultrastructure and the fact that they form in the presence of cytochalasin-D, an actin filament disrupting agent, we suggest that they are released directly into the medium rather than following the intracellular path resulting in exosome formation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM)/Ham's F-12, Earle's balanced salt solution (EBSS), Dulbecco's PBS (DPBS) (GIBCO, Grand Island, NY) and OptiPrep were obtained from Accurate Chemical Co. Westbury, NY. Newborn bovine calf serum (BCS) was purchased from Hyclone Laboratories, Logan, UT. Trypsin and deoxyribonuclease I (DNase I) were from Worthington Diagnostic Systems, Freehold, NJ. Trizma base, methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MβCD), cholesterol (CH), cholesterol oxidase, sodium dodecylsulfate (SDS), Triton X-100 (TX-100), Na2EDTA, Na2PO4, sodium pyrophosphate, sodium orthovanadate, taurocholic acid, polyethylene glycol, horseradish peroxidase, p-hydroxyphenylacetic acid, MG-132 and penicillin/streptomycin (P/S) were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co, St. Louis, MO. Complete mini EDTA-free protease inhibitor tablets were obtained from Roche Diagnostics Corp. Indianapolis, IN, while GM-6001 and Cytochalasin D were obtained from CalBiochem, La Jolla, CA. All organic solvents were purchased from Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA.

Antibodies

Rabbit polyclonal antibodies that recognize occludin, claudin-1, claudin-2, -claudin-3, and claudin-7 were from Zymed, South San Francisco, CA. Rabbit anti-caveolin-1 was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA. Rabbit anti-actin and the following HRP-conjugated polyclonal antibodies: goat anti-rabbit and rabbit anti-mouse were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO. Mouse monoclonal anti-GP135 was a gift from G. K. Ojakian.

Cell culture

MDCK II cells (CCL-34) (American Type Tissue Culture Collection, Rockville, MD) (passage levels 56–72) were maintained in antibiotic-free DMEM/Ham's F-12, 10% BCS, and were sub-cultured weekly at a split ratio of 1:6 with a medium change at 2–3 day intervals. Six days prior to an experiment, cells were plated at 2x confluence on permeable tissue culture inserts in DMEM/HAM's F12 medium, supplemented with 1% BCS, 1% P/S; the medium was changed 3 and 5 days after plating. For studies in which proteins released into the medium were examined, cells were plated on Costar inserts (4.7 cm2, 0.4 μm pore size) (Corning, Corning, NY). On rare and unpredictable occasions, monolayers treated with MβCD on the latter inserts loosened and curled at the periphery; this interferes with measurements of transepithelial electrical resistance (TER). For that reason, when TER measurements were required, the cells were plated on permeable fibrous Millicell HA inserts (0.6 cm2) (Millipore Corp. Bedford, MA) to which they remain firmly attached throughout the experiment. Changes in TER were similar to those measured on Costar inserts. Serum was omitted during incubations with MβCD.

TER measurements

The TJ integrity of the cell monolayers was evaluated at 37oC using a Millicell-ERS epithelial volt-ohmmeter (World Precision Instruments, New Haven, CT) with chopstick electrodes reproducibly placed. TER (ohms × cm2) was calculated by subtracting the contribution of the bare filter and medium from the measured TER value and multiplying by the surface area of the filter.

Cholesterol depletion

MβCD solutions were freshly prepared at a final concentration of 10 mM in DMEM/F12 and filter sterilized through a 0.2 μm filter unit. The MβCD solution was added to both the insert (apical surface) and the well (basolateral surface) and incubated at 37°C for 2 h unless otherwise stated. Media were then harvested from inserts and wells, filtered through a 0.2 μm low-protein binding filter (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) to remove any floating cells and cell debris, and prepared for Western blot analysis. In some experiments, cell monolayers were rinsed in warmed medium, and prepared for Western blotting or for CH determinations (see below).

Preparation of cholesterol-MβCD complexes

Cholesterol, 11.6 mg, was dissolved in a 2:1 methanol/chloroform mixture and added drop-wise to a continuously stirred solution of 10 mM MβCD in DMEM/F-12 in an 80°C water bath. The final CH-MβCD solution (1 mM CH/10 mM MβCD) was lyophilized and stored at −20°C. On the day of the experiment the CH-MβCD complex powder was reconstituted in DMEM/F-12 and further diluted in 10 mM MβCD to obtain three MβCD solutions containing 0.1, 0.5 and 1 mM CH, respectively.

Cholesterol determination

Cholesterol content of cell lysates was determined by the method of Goh et al [17]. Cell monolayers were incubated in lysis buffer (0.1% SDS, 10 mM Na2EDTA in 0.1 M Tris buffer, pH 7.4) for 10 min at 37°C. The lysate was sheared six times through a 27-gauge needle. To 400 μl of appropriately diluted cell lysate, was added 100 μl of a solution containing 150 mM Na2PO4, 30 mM taurocholic acid, 1.02 mM polyethylene glycol, 0.4 units of cholesterol oxidase, 0.4 units horseradish peroxidase, 0.4 mg p-hydroxyphenylacetic acid, pH 7.0. After incubation for 1 h at 37°C, 2 ml of 50 mM Na2PO4, pH 7.4 was added to stop the enzymatic reaction. Fluorescence was measured at an excitation wavelength of 325 nm and an emission wavelength of 415 nm, using an Hitachi fluorescence spectrophotometer.

Cytochalasin D

A 5 mg/ml stock solution of cytochalasin D (Cyto-D) was made in DMSO and diluted to 2 μg/ml in serum-free medium supplemented +/− 10 mM MBCD. [18].

Preparation of harvested media for Western blot analysis

Media were collected from the AP and BL compartments and filtered through a 0.2 μm low-protein binding filter to eliminate any floating cells and cell debris in the medium. Proteins in the cell-free filtrates were concentrated by adding an equal volume of 40% trichloroacetic acid (TCA). After chilling on ice for 1 h, the samples were centrifuged for 10 min at 21,000 xg. Pellets were washed three times with 95% ethanol (ETOH), to remove residual TCA, and dried overnight in a chemical hood. The dry residue was resuspended in 19.5 μl of 2% SDS in Tris buffered saline containing a cocktail of protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Samples were electrophoresed on NuPAGE 4–12% Bis-Tris gels (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and subjected to Western blotting. The blots were probed for occludin, claudin-1, -2, -3, -7, caveolin-1, GP135 and actin using the appropriate antibodies. Protein bands were detected with Western Lightening Chemiluminescence Reagent Plus (Perkin Elmer, Boston, MA) and quantified by densitometry using a Kodak Image Station 440 CF and Kodak ID Image analysis software (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY). Magic Mark XP Western Protein Standards (Invitrogen) were used to estimate the molecular weights using Quantity One Quantitation Software (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules CA).

Density gradient centrifugation

Filtrates from the AP and BL compartments were loaded onto a three-step OptiPrep gradient following a previously published protocol [2]. Briefly, one ml aliquots of filtrate were mixed with stock OptiPrep to yield a final iododixinol concentration of 30, 20 and 10%. The preparations were layered into Beckman Quick-Seal centrifuge tubes (13 × 51 mm) and centrifuged in a Vti90 vertical rotor (Beckman Co, Fullerton, CA) at 354,000 xg for 3 h at 4° C. Five 1 ml fractions were collected and mixed with an equal volume of 40% TCA. They were then processed for Western blot analysis as described above.

Electron microscopy

Confluent monolayers of control and MDCK cells on 12 mm Costar inserts were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde in DPBS followed by 1.3% OsO4 in s-collidine buffer, pH 7.4. Alternatively, to better define the extracellular space, monolayers fixed as described above were incubated with 1% tannic acid in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer, pH 7.4 [7] before dehydration with graded alcohol. All monolayers were embedded in Epon. Centrifuged pellets of the particles retrieved from the intercellular space were similarly processed for electron microscopy.

Confocal microscopy

MDCK cell monolayers were grown to confluence on 1cm2 permeable inserts. Cells were transferred to to serum-free medium supplemented with and without MBCD, each +/− Cyto-D. Monolayers were fixed for 10 min with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS, permeabilized for 10 min with 0.1% TX-100 in PBS, blocked for 15 min with 1% BSA-PBS and stained for 20 min with 50 nM Rhodamine-Phalloidin (Invitrogen) in 1% BSA-PBS. Images were acquired using a Zeiss LSM 510 confocal laser scanning microscope.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Cholesterol depletion results in a partial loss of TJ proteins from MDCK cells

During the first 30 min of MβCD mediated efflux of membrane CH from MDCK cells there was a transient rise in TER Removal of MβCD at 2h was followed by a return of TER to values equal to or greater than control cultures within 20 h (Fig. 1A). The monolayers incubated with 10 mM MβCD for 2 h were examined histologically and found to be morphologically indistinguishable from untreated controls (Fig. 1B). These observations along with the fact that cells similarly treated were shown to be 95% viable, based on release of lactate dehydrogenase into the medium [7], and that they maintained their polarized phenotype indicate that despite the reduction in CH levels, cells remained viable. Under these conditions there was a 30% decrease in cellular occludin content that was accompanied by a 22% and 26% increase in the 48 kDa and 41 kDa C-terminal peptide fragments, respectively, of occludin (Fig. 2A and 2B). Declines in the cellular levels of claudin-2, -3 and -7 were smaller than those of occludin. Levels of the cytosolic protein, actin, and the two non-tight junctional integral membrane proteins, caveolin-1 and GP135, remained essentially unchanged.

Figure 1.

MßCD induced CH efflux is associated with changes in transepithelial electrical resistance without altering monolayer morphology A. Transepithelial electrical resistance of MDCK cell monolayers treated with and without 10 mM MβCD. Control monolayers received a medium change. TER was measured at 0.5 h intervals. Monolayers treated with MβCD showed an initial 38% rise in TER, which then declined to approximately 50% of control values by 5 h. MβCD was then removed and TER recovered by 20 h. B. Sections, 1 μm thick, of MDCK cell monolayers incubated without or with 10 mM MßCD for 2h at 37°C show no discernible morphological alterations.

Figure 2.

Depletion of membrane CH results in partial proteolysis of occludin and modest decline in selected claudins. A. Western blot analysis of cell lysates from MβCD treated MDCK cell monolayers. MDCK cell monolayers were treated for 2 h with or without 10 mM MβCD. After lysis in 2% SDS, lysate proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting for occludin, claudins-2, -3 and -7. The non-TJ proteins actin, GP 135, and caveolin-1 are included for comparison. B. Intensity of staining of the electrophoresed bands was quantified by densitometry. Depletion of membrane CH was associated with a ~30% decrease in intact occludin and a 22 and 26% increase in the 41 and 48 kDa fragments of occludin, respectively. Modest decreases in claudins-2, -3, and -7 were also observed.

Occludin, its proteolytic fragments and selected claudins are released into the BL compartment upon CH depletion

It was reported, previously, that MβCD-induced CH efflux stimulated a metalloproteinase dependent shedding of selected membrane proteins, including the interleukin-6 receptor in COS-7 cells [14] and CD30 [15] in a lymphoma derived cell line, neither of which form tight junctions characteristic of normal epithelia. To determine whether a similar shedding mechanism might be responsible for the loss of TJ proteins from CH depleted membranes of a more typical epithelial cell, AP and BL media were collected from control and MβCD-treated MDCK cell monolayers. These were filtered to remove any floating cells or cell debris, and the contained protein concentrated for analysis by Western blotting as describe in Materials and Methods. Results show that TJ proteins were released primarily into the BL compartment of CH depleted cell monolayers. The amount of intact 59 kDa occludin and its 48 and 41 kDa degradation products in the BL medium was 2, 6 and 4 times greater, respectively, than that released into the AP medium (Fig. 3). Intact occludin was detected in the BL medium only in trace amounts relative to the most abundant 48 kDa fragment. With the available data we cannot determine the extent to which the decrease in TJ proteins noted in the lysate (Fig 2.) results from shedding into the medium as opposed to intracellular degradation [19]. Interestingly, the non-TJ proteins caveolin-1, GP-135 (an apical membrane marker) and actin were released exclusively into the AP medium (Fig. 3), indicating that under these conditions the TJ barrier and the polarity of the cell monolayer were maintained. The fact that caveolin-1, GP135 and actin increase in the extracellular fluid, with no detectable decrease in the amount of each associated with the cell (Fig. 2) suggests that the quantity released into the extracellular space is small relative to that in whole cell lysates. It is unlikely that the sensitivity of our Western blot quantitation, using pixel intensity data, is sufficient to detect a small difference between two large numbers derived from the cell lysates.

Figure 3.

Western blot analysis of the AP and BL media harvested from MDCK cell monolayers incubated with or without 10 mM MβCD for 2h. Tight junction proteins were released primarily into the BL medium of MβCD treated monolayers. The 48 kDa proteolytic fragment of occludin was the most prominent and intact occludin (59 kDa) was detected only in trace amounts. While claudins-2, -3, and -7 were also released into the BL medium, very little of these TJ proteins were detected in the AP medium. By contrast, caveolin-1, GP-135 and actin were released exclusively into the AP medium of MβCD treated monolayers.

The presence of actin in the apical compartment may be related to our earlier observation that the number of apical microvilli decreased following CH depletion [7]. In fact, in a recent study it was shown that during CH depletion the loss of microvilli from the apical surface of Caco-2 cells, is accompanied by direct release of plasma membrane vesicles from the tip of microvilli into the apical compartment [20]. While the lipid composition of the AP microvilli may predispose them to shed plasma membrane vesicles in response to low levels of CH, it appears that it is the lipid domain harboring the TJ complex on the BL domain that is particularly sensitive to alterations in CH content.

MβCD induced release of TJ proteins into the BL medium accelerates over time

A time course study of the release of integral TJ proteins (occludin, occludin related fragments, claudin-2) into the BL medium, indicated that the amount of native occludin and its lower molecular weight proteolytic fragments began to appear within 30 min of adding MβCD (Fig. 4A and B). The rate of release accelerated between 60 and 150 min after the addition of MβCD, with the 48 kDa occludin fragment predominating. Caveolin-1, which is located in both the AP and BL membrane, was not released from the BL membrane during CH efflux (Fig. 3). While the reasons for this are unclear, it may be related to the fact that caveolin-1 exists as a heterodimer with caveolin-2 in the BL membrane [21].

Figure 4.

Release over time of occludin, its proteolytic fragments and claudin-2 into the BL medium during incubation of MDCK cell monolayers with 10 mM MβCD. A. Western blot analysis revealed that the release of the 48 kDa proteolytic fragment of occludin into the BL medium occurred within 30 min of adding MßCD. By contrast trace amounts of intact occludin, its 41 kDa proteolytic fragment and claudin-2 were detectable after 30 minutes of CH depletion. Caveolin-1 was not detected in the BL medium at any of the time points. B. The rate of release into the medium of the 48 kDa occludin fragment was accelerated relative to that of either intact occludin or its 41 kDa fragment.

Release of occludin and its lower molecular weight fragments continues when MβCD is removed after one hour of incubation

To determine whether continuous contact of MβCD with the cell monolayers was necessary for the continued proteolysis and release of TJ proteins into the medium, monolayers were incubated with 10 mM MβCD for 0.5, 1, or 1.5 h and then transferred to fresh medium without MβCD for the remainder of a 3 h incubation. Western blot analysis of the MβCD-free BL media (Fig. 5A), collected at the end of 3 h and CH measurements made after 0, 1, and 2 h of incubation with MβCD indicated that a 60% decrease in CH, achieved after a 1 h incubation with MβCD (Fig. 5B), was sufficient to initiate events culminating in the sustained release of occludin-related peptides into the BL medium, even after MβCD was removed.

Figure 5.

Occludin and its degradation products continue to be released after removal of MβCD. A. Cell monolayers were incubated with 10 mM MβCD for 0, 0.5, 1 or 1.5 h and then transferred to fresh medium without MβCD for the balance of the 3 h incubation period. Western blot data revealed that the reduction in CH achieved after 1 h of incubation with 10 mM MβCD was sufficient to trigger the continued release of occludin and its degradation products, predominantly the 48 kDa fragment, into the BL medium (lane 3). Exposure to MβCD for 30 min was insufficient to trigger this release. B. Cholesterol content of MDCK cell monolayers after a 1 and 2 h incubation with MβCD. Incubation for 1 h with 10 mM MβCD reduced cellular CH levels to approximately 60% of control values.

To confirm that the release of TJ proteins into the medium was related to the removal of membrane CH and not due to some unknown interaction between the cells and MβCD, monolayers were incubated with 10 mM MβCD pre-loaded with 0.1, 0.5 or 1 mM CH. Monolayers incubated with medium, +/− 10 mM MβCD, were included as positive and negative controls, respectively. All incubations were for 2 h at 37°C and the BL medium from each well was processed as described above. Western blot analysis (Fig. 6) of the samples showed that when the CH binding sites of MβCD were occupied by 0.5 to 1.0 mM of exogenous CH, no occludin peptides were released into the BL medium. This supports the notion that the release of occludin and its degradation products into the BL medium is a direct consequence of MβCD induced CH efflux and not the result of non-specific interactions between MβCD and MDCK cells. Similar conclusions were reached from experiments in which MβCD preloaded with CH was shown to prevent the fall of CH and alterations in TER observed when CH synthesis was depressed by Lovastatin, an inhibitor of HMG-CoA reductase [5].

Figure 6.

Pre-loading MβCD with CH obviates release of TJ proteins into the BL medium. MDCK cell monolayers were incubated with 10 mM MβCD loaded with 0.1, 0.5 or 1 mM CH (lanes 3, 4, 5). Control monolayers were incubated with either medium alone or with 10 mM MβCD to which no CH had been added (lanes 1 and 2). All incubations were of 2 h duration. The BL medium was then collected as described in Materials and Methods and analyzed by Western blotting. When all the acceptor sites in MβCD are occupied by exogenous CH (lanes 4 and 5), occludin is not released into the BL medium.

A metalloproteinase dependent cleavage of occludin is associated with rapid MβCD-induced efflux of CH

Previous studies have shown that depletion of membrane CH is associated with activation of metalloproteinases, including ADAM 10 (ADAM, a disintegrin and metalloproteinase), ADAM 17 [14, 15, 22], MT1-MMP and MMP2 [23, 24]. To determine whether activation of metalloproteinases by the rapid removal of membrane CH is associated with the formation of the 41 and 48 kDa occludin fragments, monolayers were incubated for 2 h with 10 mM MβCD +/− GM6001, a potent broad-spectrum inhibitor of metalloproteases [25]. The BL media were harvested and concentrated as described above; the cell monolayers were lysed in 2% SDS. The proteins in the concentrated BL media, as well as those in lysates were analyzed by Western blotting. The inhibitor, at both concentrations tested, increased the amount of native occludin (59 kDa) in the BL medium and markedly reduced that of the two occludin fragments (48 and 41 kDa) (Fig. 7A). The intensity of the 48 kDa band was reduced by 70% and the 41 kDa fragment was virtually absent when GM6001 was included. Based on the estimated size of the two fragments and the fact that both are recognized by the anti-occludin antibody directed at the C-terminus of occludin, we have tentatively localized the cut sites of the enzyme(s) to a region on the first extracellular loop of occludin to yield the 48 kDa C-terminal fragment and on its small intracellular loop to yield the 41 kDa C-terminal fragment (Fig. 7C). By contrast, in whole cell lysates, inclusion of 100 μM GM6001 during the incubation with MβCD reduced the amount of the 48 kDa occludin fragment to control levels, and did not appear to change the level of the 41 kDa fragment (Fig. 7B). Note that, even in control cells not exposed to MβCD, both degradation fragments are present. That being the case, having GM6001 present during the 2 h incubation might not be expected to decrease either band appreciably.

Figure 7.

The metalloprotease inhibitor, GM6001, decreases the amount of proteolytic occludin fragments released into the BL medium during CH efflux. A. Monolayers of MDCK cells were incubated for 2 h with 10 mM MβCD without GM6001 (lane 1) or with 50, or 100 μM GM6001 (lanes 2 and 3). Protein in the BL compartment was collected, concentrated and analyzed by Western blotting. When the concentration of GM6001 was increased to 50 mM or more, occludin proteolytic fragments released into the BL medium were markedly reduced and intact occludin was increased. B. After harvesting the media, the monolayers were lysed and prepared for Western blot analysis. Addition of 100 mM GM6001 primarily reduced the amount of the 48 kDa degradation product in the cells. C. Diagram of the occludin molecule. Each black dot represents an amino acid. Brackets indicate the approximate location of cut sites that produce the 48 and 41 kDa fragments.

Intact occludin continued to be released into the BL medium in the presence of GM6001 (Fig. 7A), indicating that cleavage of occludin by metalloproteinases is not a prerequisite for the release of the membrane bounded particles into the intercellular space during CH efflux and is consistent with a model in which their release may be the direct consequence of membrane CH depletion. Although stimulation of occludin proteolysis is associated with CH efflux, the data do not distinguish whether the action of the metalloproteinase occurs prior to, during and/or after release of the membrane bounded particles. Application of the proteasome inhibitor MG132 did not prevent the formation of the two proteolytic fragments of occludin (data not shown). It would be of interest, to determine whether cleavage within the first extracellular loop must precede the cleavage that occurs in the cytosolic loop. Such sequential cleavage of membrane proteins by metalloproteinases has been described in other systems [19]. Whether these fragments, which are observed at low levels in control cells, are of functional significance or are simply intermediates in the degradation of occludin is presently not known.

That occludin, but not claudins or ZO-1, might be a substrate for metalloproteinase enzymes was inferred from observations made in cultured endothelial cells showing that protein tyrosine phosphatase inhibitors (phenylarsine oxide and pervanadate) induced occludin proteolysis, a response that was sensitive to metalloproteinase inhibition but not by other protease inhibitors [26, 27]. In both studies only the higher molecular weight proteolytic fragment of occludin was detected. Subsequent studies have shown that a number of other classes of proteases, including cysteine and serine proteases found in dust mite fecal pellets, can cleave occludin, [28]. These, however, appear to cut at sites located in both extracellular loops of occludin. By contrast, application of trypsin in calcium sufficient medium to intact monolayers of MDCK cells not only fails to cleave occludin, but induces the rapid formation of aberrant TJ strands [29] in the basolateral membrane, an observation that supports data indicating that, in addition to their location in the TJ, both occludin [30] and claudins [31] are also distributed in the basolateral membrane. Thus it appears that the rapid removal of membrane CH exposes a unique second intracellular site that is cleaved to yield the 41 kDa fragment. Which of the several metalloproteinases mentioned above is responsible for the cleavage of occludin is at present unclear. It will be of interest in a future study to utilize siRNA technology in order to identify the specific metalloproteinases that are activated during CH depletion.

Incubation of cell monolayers with MβCD results in the accumulation of membrane bounded particles in the intercellular space

We had previously reported that treatment of MDCK cell monolayers with MβCD resulted in the appearance of membrane bounded particles in the intercellular space and a reduction in the number of apical microvilli [7] and Fig 8 A,B. To determine whether occludin and its proteolytic fragments, as well as actin, caveolin-1 and GP-135, might be associated with these particles, MDCK cell monolayers were incubated with 10 mM MβCD for 2 h. The AP and BL media were harvested, passed through a 0.2 μm low-protein binding filter, to eliminate floating cells and cell debris. The filtrate was centrifuged at 208,861 xg overnight at 4°C. The resulting supernatants and pellets were precipitated with TCA and processed for Western blot analysis (Fig 8C). The 48 kDa occludin fragment in the BL medium was distributed nearly equally between the supernatant and pellet fractions, while the 41 kDa fragment was localized primarily to the supernatant. Although the total amounts of occludin-related peptides in the AP solution were less than those in the BL solution, virtually all were present in the high-speed pellet. Only trace quantities of intact occludin were observed in fractions from either AP or BL media. Actin, caveolin-1 and GP135 were detected exclusively in the AP medium. While caveolin-1 and GP-135 were completely sedimented after high-speed centrifugation, actin was equally distributed between the supernatant and pellet fractions. Together these data suggest that the population of membrane particulates released from the AP surface differs markedly in protein composition from those released from the BL domain. They indicate, further that there are at least two particle populations in the BL compartment. One is a nonsedimenting population that includes C-terminal fragments which are produced by cleavage at one or the other metalloproteinase-sensitive sites. The other is recovered in the pellet and, contains primarily the 48 kDa occludin C-terminal fragment that results from the cleavage at the first external loop of occludin.

Figure 8.

Extracellular membrane-bounded particles released from the BL surface of cells treated with MβCD may contain membrane microdomains enriched for TJ-related peptides A. Electron micrograph of control MDCK cells cultured in a Costar Transwell tissue culture insert. Tannic acid added to the fixative delineates the interdigitating adjacent cell membranes. B. Electron micrograph of MDCK cells incubated with 10 mM MβCD for 2h and fixed as described in A. Membrane bounded particles are observed in the intercellular space and in the pores of the substratum (arrow). Scale bars shown in A and B equal 1 micron. C. Sedimentation of selected proteins released during incubation with MβCD. After incubation with 10 mM MβCD for 2 h, AP and BL media were filtered through 0.2 μm filters. The filtrate was centrifuged overnight at 208,861 xg and both supernatant (S) and pellet (P) were processed for Western blot analysis. The 48 and 41 kDa occludin fragments in the BL medium were partially sedimented, while those in the AP medium were completely sedimented by high-speed centrifugation. All of the released actin, caveolin-1 and GP-135 were retrieved in the AP medium and, of these proteins caveolin-1 and GP-135 were completely sedimented by high-speed centrifugation. D. To determine whether occludin and its degradation products in the BL medium reside in a buoyant fraction, the BL filtrate was subjected to OptiPrep density gradient centrifugation. Five 1-ml fractions were collected with fraction I being the least dense and fraction V the most dense. The protein in each fraction was concentrated and processed for Western blot analysis. Occludin and its degradation products were detected in fraction IV, with a density of 1.15 g/ml.

Published studies [2, 11] showing that TJ proteins may reside in detergent resistant, CH-enriched microdomains suggest the possibility that changes in physical properties of the latter, following CH depletion, results in shedding of membrane-bounded particles enriched for occludin and its two proteolytic C-terminal fragments. To examine this possibility, filtrate from the BL medium was subjected to OptiPrep density gradient centrifugation as described in Methods and Materials. Five 1 ml fractions were harvested and labeled I through V in order of increasing density. The protein in each fraction was concentrated by TCA precipitation and processed for Western blot analysis. Intact occludin and its two cleavage products were located in fraction IV that had a density of 1.15 g/mL (Fig. 8D), a value similar to that reported for occludin in TX-100 lysates of MDCK cells subjected to OptiPrep density gradient centrifugation under similar conditions [2]. Further studies using detergent-resistant-markers such as flotillin will be necessary before we can conclude, definitively, that TJ proteins in the extracellular fluid are components of detergent resistant membranes.

Two possible mechanisms could potentially yield extracellular, membrane bounded particles containing TJ proteins following CH depletion [16]. One is that regions of the plasma membrane, enriched for occludin and other TJ proteins are endocytosed to be subsequently released into the medium as components of an exosome [32]. However, our ultrastructural images suggest an alternative route in which regions of the plasma membrane bud off directly from the BL membrane into the intercellular space (Fig. 9A and B). Such a mechanism has been shown to account for the accelerated release of extracellular membrane vesicles from microvilli on the apical surface of epithelial cells after CH depletion [20] as well as the budding of influenza viruses from infected cells. [33]. Regardless of the path taken, at some point in the process, there is an increase in the rate at which occludin in the CH depleted membrane is cleaved by metalloproteinases. To examine the ultrastructure of these MβCD induced particles, they were harvested as follows: After incubation with MβCD for 2 h, particles trapped between the cells were released into the apical medium by replacing the MβCD solution with Ca++-free DPBS for 30 min. This `opened' the TJs, allowing membrane particulates to be washed into the apical solution (Fig. 9A) from which they were recovered by centrifugation and examined by electron microscopy. The pellet was found to contain membrane bounded particles that ranged in diameter from 31 to 62 nm and contained internal filamentous material resembling actin filaments as well as fine filaments on the external surface. The ultrastructural appearance of these particles suggests that they were formed by budding from the cell surface, rather than by an endocytotic mechanism that leads to the formation of exosomes [34] (Fig. 9B). Pellets from duplicate samples were analyzed by Western blotting and found to contain both 48 and 41 kDa occludin fragments as well as smaller amounts of intact occludin (Fig. 9C).

Figure 9.

Occludin and its degradation products are associated with the intercellular particles trapped between cells. A. MβCD treated monolayers were incubated with calcium-free PBS to open the tight junctions and the intercellular particles (inset) released into the AP medium were retrieved by centrifugation. Scale bar equals 1 micron; inset scale bar equals 100nanometers. B. The AP medium, harvested from MβCD treated monolayers, incubated with calcium-free PBS, was subjected to high-speed centrifugation and the pellets were processed for electron microscopy. Membrane bounded particles, ranging from 31 to 62 nm in diameter, are detected in the pellet. They contain fibrillary, electron dense material surrounded by plasma membrane from which delicate electron dense fibrils project. Scale bar equals 100 nanometers. C. Western blot analysis of the particles retrieved from MβCD treated monolayers showed the presence of occludin and its degradation products. Only trace amounts of intact occludin and the 48 kDa fragment are detected in the AP medium from cell monolayers not exposed to MβCD, but incubated with calcium-free PBS.

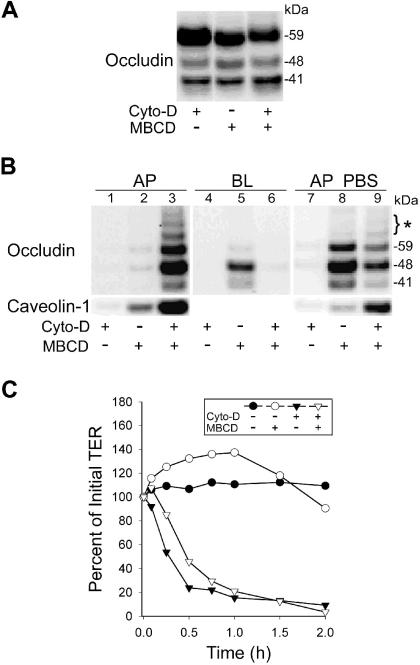

To determine the extent to which shedding of these intercellular particles is dependent on an intact actin filament network, confluent MDCK cell monolayers were incubated with MβCD +/− Cytochalasin D (Cyto-D) for 2 h at 37°C. In the current study Cyto-D alone had no effect on levels of cell-associated occludin (Fig. 10A) or claudins (data not shown). However, addition of MβCD in combination with Cyto-D reduced cell occludin levels below that observed with MβCD alone (Fig. 10A). None of the proteins examined in the current study were detected in either the AP or BL medium of cells treated for 2 h with only Cyto-D (Fig. 10 B, lanes 1 and 4), with minor amounts detected in the AP fluid when the monolayer was incubated for an additional 30 min with PBS. (Fig. 10B, lane 7). We conclude from these studies that, despite causing TER to fall abruptly, Cyto-D, in the absence of MβCD, does not induce the release of particle bound occludin peptides.

Figure 10.

Release of TJ-related proteins after CH depletion occurs by an actin independent mechanism. A. Incubation of MDCK cell monolayers with MβCD or MβCD with Cyto-D is associated with a decline in the levels of native occludin in the cells. Three confluent monolayers of MDCK cells were cultured in Costar inserts. The first was incubated with Cyto-D, the second with MβCD and the third monolayer with both Cyto-D and MβCD. The decline in cellular content of intact, 59 kDa, occludin is most pronounced when both Cyto-D and MβCD are present. B. Analysis of media harvested from control or MβCD treated monolayers, each +/− Cyto-D. At the end of the 2 h incubation, AP media (lanes B1–3) and BL media (lanes B4–6) were collected. To insure complete disassembly of TJs, PBS was added to the three monolayers for 30 min (lanes B7–9), and then collected for analysis. All AP and BL solutions were processed as described in Materials and Methods and Western blots analyzed for occludin and caveolin-1. C. MDCK cell monolayers incubated with Cyto-D alone (filled triangles) or in combination with MβCD (empty triangles), showed a rapid decline in TER. In monolayers that were treated with 10 mM MβCD alone (empty circles) there is an initial rise followed by a fall in TER. Control monolayers (filled circles) underwent a medium change at the time that the experimental monolayers received MβCD and/or Cyto-D.

When monolayers were incubated with MβCD alone, no particulates with occludin peptides were recovered in the AP solution after 2h (Fig 10B, lane 2). The BL solution contained the 48 kDa and lesser amounts of the 41 kDa peptide along with trace amounts of intact occludin (Fig. 10B, lane 5). Under these conditions TER was only slightly less than control values after 2h of incubation with MβCD (Fig. 10C), suggesting that an intact TJ barrier prevented particulates from diffusing into the AP compartment. Consistent with this idea was the observation that when TJs were opened with calcium-free PBS, particle bound occludin fragments diffused into the AP fluid compartment (Fig. 10, lane 8). Unlike the BL fraction, the apical fluid contained intact, 59 kDa occludin.

In contrast to the other AP fluids examined, those from monolayers incubated simultaneously with MβCD and Cyto-D contained the greatest quantities of occludin peptides with the 48 kDa fragment and intact occludin being most prominent (Fig. 10B, lane 3). Interestingly, high molecular weight forms of occludin (>59 kDA) were observed when Cyto-D was present and likely represent phosphorylated forms of the protein [30]. In view of the fact that TER of the monolayers treated with both MβCD and Cyto-D declined to zero within 1h (Fig. 10C) it is likely that membrane particulates shed from the BL surface of the CH depleted cells diffused readily into the AP solution. This being the case, it is not surprising that only traces of occludin peptides were harvested from the BL solution (Fig. 10B, lane 6). Further disassembly of TJs following incubation with PBS (Fig. 10B, lane 9) resulted in additional recovery of smaller amounts of occludin peptides whose relative abundance was similar to that observed in the AP fluid obtained from these monolayers.

The data in Fig. 10 do not support a CH efflux-related shedding of membrane particulates via an actin-dependent endocytic mechanism. Instead, our ultrastructural images show direct budding of particles from the basolateral surface (Fig. 9A). Furthermore, they suggest that Cyto-D, by disrupting the actin cytoskeleton, widens the paracellular pathway sufficiently to allow passage of intercellular particles, enriched in occludin peptides, to diffuse into the AP compartment following the depletion of membrane CH. They indicate further that there are at least two pools of particles, those able to diffuse from the intercellular space into the BL medium and a more complex mixture of particles trapped between cells that can only be harvested when the TJ is opened either with Cyto-D or the removal of calcium by PBS. It is conceivable that the particles obtained from the BL fluid are derived from the BL membrane, while those in the more complex mixture, that includes phosphorylated occludin [30], are derived from the BL membrane and from the TJ itself. In fact Cyto-D, by disturbing the peri-junctional actin ring, may disrupt associations between integral TJ proteins and the actin cytoskeleton in such a way as to facilitate the budding of membrane vesicles and their release into the extracellular space.

To show that Cyto-D did, in fact, cause significant redistribution of actin, cells were stained with phalloidin and examined by confocal microscopy. In contrast to control monolayers (Fig 11A), application of Cyto-D resulted in the loss of filamentous actin in stress fibers and accumulation of granular fragments of actin at the plasma membrane (Fig. 11B). These observations confirm those of an earlier study which showed that Cyto-D reduced TER and altered the organization of the perijunctional actin ring and the more basally located stress fibers [18]. Although filamentous actin was partially preserved in stress fibers of cells incubated with MßCD, actin was found to accumulate at tricellular regions (Fig. 11C) as reported previously [7, 18]. When monolayers were incubated with both Cyto-D and MßCD, disassembly of actin stress filaments was similar to that seen when only Cyto-D was present, however, instead of being dispersed around the periphery of the cells, the actin was more concentrated in the tricellular area than when cells were incubated with MßCD, alone (Fig. 11D)._

Figure 11.

Cyto D alone or in combination with MßCD causes reorganization of MDCK cell cytoskeleton. Cells were stained with phalloidin to reveal images of actin localization. A. In control, untreated monolayers of MDCK cells, actin filaments are distributed throughout the cytoplasm. B. In monolayers treated with Cyto-D actin appears as cytoplasmic granules as well as aggregates at the cell membrane. C. In cells treated with MßCD, filamentous actin is preserved but is associated with accumulation of actin at tricellular regions of the TJ. D. Incubation of MDCK cell monolayers with both MßCD and Cyto-D results in the complete loss of filamentous actin and a marked accumulation of actin at the tricellular regions of the TJ. Scale bar equals 10 microns.

There are some interesting parallels between the response of MDCK cells to CH depletion, described above, and the events occurring when dendritic cells are stimulated by toll-like-receptor ligands [35]. In the latter instance, cells reorganize their actin cytoskeleton, and promote the ADAM-17 dependent disassembly of their podosomes. It would be of interest to know whether, in these studies there was any evidence of vesicle shedding similar to that observed in the present study. Whether ADAM-17 or another metalloproteinase is responsible for occludin proteolysis in the CH depleted membrane of dendritic cells is a subject for future studies.

In conclusion, our earlier studies showed that when levels of CH in epithelial cells are reduced, there is a decrease in the barrier function of TJs and a coincident loss of occludin, a TJ integral membrane protein. In addition actin was observed to concentrate at the tricellular areas and vesicles accumulated in the intercellular space [7]. Data from the current study suggest that at low levels of CH there is extensive restructuring of the plasma membrane that includes disassembly of the TJs, activation of surface metalloproteinases that cleave occludin, reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton and release of extracellular vesicles enriched for two proteolytically derived C-terminal occludin peptides._

While cells, in vivo, are not likely to experience the rapid and extreme changes in their CH levels, reported here and in other studies [36], agents such as MßCD used in vitro, provide insight into the role played by CH in cell structure and function [2, 5–7, 37–40]. For example disassembly of the junctional complex during the epithelial-mesenchymal-transition as well as the migration of both normal and tumor cells through the extracellular matrix are sensitive to changes in CH content [37, 41–44]. Although speculative, it is conceivable that information derived from studies with MßCD and other agents that modulate cell CH levels, may provide a rationale for future development of therapeutics that would enhance or depress these activities, in vivo.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by NIH grants HL25822 and HL36781.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- [1].Edidin M. The state of lipid rafts: From model membranes to cells. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 2003;32:257–283. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.32.110601.142439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Lynch RD, Francis SA, McCarthy KM, Casas E, Thiele C, Schneeberger EE. Cholesterol depletion alters detergent-specific solubility profiles of selected tight junction proteins and the phosphorylation of occludin. Exp. Cell Res. 2007;313:2597–2610. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Van Itallie CM, Gambling TM, Carson JL, Anderson JM. Palmitoylation of claudins is required for efficient tight junction localization. J. Cell Sci. 2005;118:1427–1436. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Schneeberger EE, Lynch RD, Kelly CA, Rabito CA. Modulation of tight junction formation in clone 4 MDCK cells by fatty acid supplementation. AJP: Cell Physiology. 1988;254:C432–C440. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1988.254.3.C432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Stankewich MC, Francis SA, Vu QU, Schneeberger EE, Lynch RD. Alterations in cell cholesterol content modulate of calcium induced tight junction assembly by MDCK cells. Lipids. 1996;31:817–828. doi: 10.1007/BF02522977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Lynch RD, Tkachuk LJ, Ji X, Rabito CA, Schneeberger EE. Depleting cell cholesterol alters calcium-induced assembly of tight junctions by monolayers of MDCK cells. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 1993;60:21–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Francis SA, Kelly JM, McCormack JM, Rogers RA, Lai J, Schneeberger EE, Lynch RD. Rapid reduction of MDCK cell cholesterol by methyl-β-cyclodextrin alters steady state transepithelial electrical resistance. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 1999;78:473–484. doi: 10.1016/s0171-9335(99)80074-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Furuse M, Hirase T, Itoh M, Nagafuchi A, Yonemura S, Tsukita S, Tsukita S. Occludin: A novel integral membrane protein localizing at tight junctions. J. Cell Biol. 1993;123:1777–1788. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.6.1777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Furuse M, Fujita K, Fujimoto K, Tsukita S. Claudin 1 and 2: Novel integral membrane proteins localizing at tight junctions with no sequence similarity to occludin. J. Cell Biol. 1998;141:1539–1550. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.7.1539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Ikenouchi J, Furuse M, Furuse K, Sasaki H, Tsukita S, Tsukita S. Tricellulin constitutes a novel barrier at tricellular contacts of epithelial cells. J. Cell Biol. 2005;171:939–945. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200510043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Nusrat A, Parkos CA, Verkade P, Foley CS, Liang TW, Innis-Whitehouse W, Eastburn KK, Madara JL. Tight junctions are membrane microdomains. J. Cell Sci. 2000;113:1771–1781. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.10.1771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Traweger A, Fang D, Liu YC, Stelzhammer W, Krizbai IA, Fresser F, Bauer HC, Bauer HL. The tight junction-specific protein occludin is a functional target of the E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase itch. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:10201–10208. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111384200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Pollack-Charcon S, Ben-Shaul Y. Degradation of tight junctions in HT29, a human colon adenocarcinoma cell line. J. Cell Sci. 1979;35:393–402. doi: 10.1242/jcs.35.1.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Matthews V, Schuster B, Schuetze S, Bussmeyer I, Ludwig A, Hundhausen C, Sadowski T, Saftig P, Hartmann D, Kallen K-J, Rose-John S. Cellular cholesterol depletion triggers shedding of the human interleukin-6 receptor by ADAM10 and ADAM17 (TACE) J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:38829–38839. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210584200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].von Tresckow B, Kallen K-J, von Strandmann EP, Borchmann P, Lange H, Engert A, Hansen HP. Depletion of celular cholesterol and lipid rafts increases shedding of CD30. J. Immunol. 2004;172:4324–4331. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.7.4324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Cocucci E, Racchetti G, Meldolesi J. Shedding microvesicles: artefacts no more. Trends in Cell Biology. 2009;19:43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Goh EH, Krauth DK, Colles SM. Analysis of cholesterol and desmosterol in cultured cells without organic solvent extraction. Lipids. 1990;25:738–741. doi: 10.1007/BF02544043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Stevenson BR, Begg DA. Concentration-dependent effects of cytochalasin D on tight junctions and actin filaments in MDCK epithelial cells. J. Cell Sci. 1994;107:367–375. doi: 10.1242/jcs.107.3.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Tousseyn T, Thathiah A, E. J, Raemaekers T, Konietzko U, Reiss K, Hartmann D, De Strooper B. ADAM10, the rate-limiting protease of regulated intramembrane proteolysis of Notch and other proteins, is processed by ADAMS-9, ADAMS-15 and γ-secretase. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2009;284:11738–11747. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805894200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Marzesco AM, Wilsch-Brauninger M, Dubreuil V, Janich P, Langenfeld K, Thiele C, Huttner WB, Corbeil D. Release of extracellular membrane vesicles from microvilli of epithelial cells is enhanced by depleting membrane cholesterol. FEBS Lett. 2009;583:897–902. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.01.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Scheiffele P, Verkade P, Fra AM, Virta H, Simons K, Ikonen E. Caveolin-1 and -2 in the exocytic pathway of MDCK cells. J. Cell Biol. 1998;140:795–806. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.4.795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Tellier E, Canault M, Rebsomen L, Bonardo B, Juhan-Vague I, Nolbone G, Peiretti F. The shedding activity of ADAM17 is sequestered in lipid rafts. Exp. Cell Res. 2006;312:3969–3980. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2006.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Atkinson SJ, English JL, Holway N, Murphy G. Cellular cholesterol regulates MT1 MMP dependent activation of MMP 2 via MEK-1 in HT1080 fibrosarcoma cells. FEBS Lett. 2004;566:65–70. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.04.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Mazzone M, Baldassarre M, Beznoussenko G, G. G, Cao J, Zucker S, Luini A, Buccione R. Intracellular processing and activation of membrane type 1 matrix metalloprotease depends on its partitioning into lipid domains. J. Cell Sci. 2004;117:6275–6287. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Santiskulvong C, Rozengurt E. Galardin (GM6001), a broad-spectrum matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor, blocks bombesin-and LPA-induced EGF receptor transactivation and DNA synthesis in rat-1 cells. Exp. Cell Res. 2003;290:437–446. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(03)00355-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Wachtel M, Frei K, Fontana A, Winterhalter K, Gloor SM. Occludin proteolysis and increased permeability in endothelial cells through tyrosine phosphatase inhibition. J. Cell Sci. 1999;112:4347–4356. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.23.4347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Lohmann C, Krischke M, Wegener J, Galla H-J. Tyrosine phosphatase inhibition induces loss of blood-brain barrier integrity by matrix metalloproteinase-dependent and -independent pathways. Brain Res. 2004;995:184–196. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Wan H, Winton HL, Soeller C, Taylor GW, Gruenert DC, Thompson PJ, Cannell MB, Stewart GA, Garrod DR, Robinson C. The transmembrane protein occludin of epithelial tight junctions is a functional target for serine peptidases from faecal pellets of Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus. Clin. Exp. Allergy. 2001;31:279–294. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2001.00970.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Lynch RD, Tkachuk LJ, McCormack JM, McCarthy KM, Rogers RA, Schneeberger EE. Basolateral but not apical application of protease results in a rapid rise of transepithelial electrical resistance and formation of aberrant tight junction strands in MDCK cells. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 1995;66:257–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Sakakibara A, Furuse M, Saitou M, Ando-Akatsuka Y, Tsukita Y. Possible involvement of phosphorylation of occludin in tight junction formation. J. Cell Biol. 1997;137:1393–1401. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.6.1393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Peter Y, Goodenough DA. Claudins. Curr. Biol. 2004;14:R293–R294. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.03.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Stoeck A, Keller S, Riedle S, Sanderson MP, Runz S, Le Naour F, Gutwein P, Ludwig A, Rubinstein E, Altevogt P. A role for exosomes in the constitutive and stimulus-induced ectodomain cleavage of L1 and CD44. Biochem. J. 2006;393:609–618. doi: 10.1042/BJ20051013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Barman S, Nayak DP. Lipid raft disruption by cholesterol depletion enhances influenza A Virus budding from MDCK cells. J. Virol. 2007;81:12169–12178. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00835-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Van Niel G, Heyman M. The epithelial cell cytoskeleton and intracellular trafficking II. Intestinal epithelial cell exosomes: perspectives on their structure and function. American Journal of Physiology: Gastrointestinal Liver Physiology. 2002;283:G251–G255. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00102.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].West MA, Prescott AR, Chan KM, Zhou Z, Rose-John S, Scheller J, Watts C. TLR ligand-induced podosome disassembly in dendritic cells is ADAM17 dependent. J. Cell Biol. 2008;182:993–1005. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200801022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Lange Y, Steck TL. How cholesterol homeostasis is regulated by plasma membrane choesterol in excess of phopholipids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:11664–11667. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404766101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Caldieri G, Giacchetti B, Beznoussenko G, Attanasio F, Buccione R. Invadopodia biogenesis, is regulated by caveolin-mediated modulation of membrane cholesterol levels. J. Cell. Molec. Med. 2008 doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00568.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1582–4934.2008.00568.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Gutwein P, Mechtersheimer S, Riedle S, Stoeck A, Gast D, Joumaa S, Zentgraf H, Fogel M, Altevogt P. ADAM-10-mediated cleavage of L1 adhesion molecule at the cell surface and in released membrane vesicles. The FASEB Journal. 2003;17:292–294. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0430fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Telbsza A, M. M, Ozvegy-Laczkaa C, Homolyaa L, Szenteb V, Sarkadia B. Membrane cholesterol selectively modulates the activity of the human ABCG2 multidrug transporter. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta - Biomembranes. 2007;1768:2698–2713. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Zuo W, Chen Y-G. Specific activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase by transforming growth factor-receptors in lipid rafts is required for epithelial cell plasticity. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2009;20:1020–1029. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-09-0898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Atkinson S, English J, Holway N, Murphy G. Cellular cholesterol regulates MT1-MMP dependent activation of MMP-2 via MEK-1 in HT1080 fibrosarcoma cells. FEBS Lett. 2004;566:65–70. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.04.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Harten SK, Shukla D, Barod R, Hergovich A, Balda MS, Matter K, Esteban MA, Maxwell PH. Regulation of renal epithelial tight junctions by the von Hippel-Lindau tumor supressor gene involves occludin and claudin-1 and is independent of E-cadherin. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2009;20:1089–1101. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-06-0566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Ikenouchi J, Matsuda M, Furuse M, Tsukita S. Regulation of tight junctions during the epithelium-mesenchyme transition: direct repression of the gene expression of claudins/occludin by Snail. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2009 doi: 10.1242/jcs.00389. http://www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E08-06-0566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Kim S, Kim Y, Lee K, Chung J. Cholesterol inhibits MMP-9 expression in human epidermal keratinocytes and HaCaT cells. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:3869–3874. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.06.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]