Summary

We wanted to test the psychometric reliability and validity of self-reported information on psychological and functional status gathered by computer in a sample of primary care outpatients. Persons aged 65 years and older visiting a primary care medical practice in Baltimore (n = 240) were approached. Complete baseline data were obtained for 54 patients and 34 patients completed 1-week retest follow-up. Standard instruments were administered by computer and also given as paper and pencil tests. Test–retest reliability estimates were calculated and comparisons across mode of administration were made. Separately, an interviewer administered a questionnaire to gauge patient attitudes and feelings after using the computer. Most participants (72%) reported no previous computer use. Nevertheless, inter-method reliability of the GDS15 at baseline (0.719, n = 47), intra-method reliability of the computer in time (0.797, n = 31), inter-method reliability of the CESDR20 at baseline (0.740, n = 53), and the correlation between the CESDR20 computer version at baseline and follow-up (0.849, n = 34) were all excellent. The inter-method reliability of the CESDR20 at follow-up (0.615, n = 37) was lower but still acceptable. Although 28% were anxious prior to using the computer testing system, that percent decreased to 19% while using the system. The efficiency and reliability in comparison to the paper instruments were good or better. Even though most participants had not ever used a computer prior to participating in the study, they had generally favorable attitudes toward the use of computers, and also reported having favorable experience with the computer testing system.

Keywords: Primary care, Depression, Computerized assessment, Geriatrics

1. Introduction

The primary care physician occupies a strategic position to be a case-finder and coordinator for the care of elderly persons. Nevertheless primary care physicians often do not have the time or means for carrying out a complete geriatric assessment, and an effective computer-assisted assessment tool might facilitate the ability to evaluate patients and assess change. The development of practical assessment tools is important because certain aspects of geriatric assessment, especially depression, are not commonly addressed in primary care settings in any standardized way.

Several factors make primary health care services relevant as a location for automated assessment for mental health care of older persons. First, older persons usually make several visits per year to their doctor. Second, chronic medical illnesses (e.g. cardiovascular disease, arthritis, and diabetes mellitus) often co-occur with depression among older persons presenting in primary care, complicating the recognition and treatment of major depression and other mental disturbances. Third, the majority of patients with depression may be treatable by the primary care physician, and innovative methods can facilitate the treatment process. Although primary care physicians have a low recognition rate of alcohol, drug abuse, and mental health disorders, and are pessimistic about patients' outcomes even with treatment, primary care physicians prescribe the majority of tricyclic and anxiolytic medications [1]. Not only does depression appear to result in over-utilization of health care resources, but depression may worsen the outcome of other medical conditions such as myocardial infarction [2,3].

Recent research suggests that identification and treatment of depressive disorders in primary care are more complex than previously assumed. Competing demands vie for the attention of the clinician, with insufficient time to address all demands [4]. The relatively poor detection and treatment of depression in the elderly is not due to lack of concern on the part of the physician but rather lack of time resources. Integration of efficient computerized systems for detection of depression into the practice ecosystem has considerable potential to effectively provide more time allocated to patient assessment, without requiring as much staff time [4]. We developed a computer-assisted assessment device, which could be used to efficiently screen elderly outpatients for changes in psychological and functional status. The purpose of this study was to assess the reliability of our instrument, comparing computer administration to paper and pencil among older primary care patients.

2. System description

2.1. Computer application

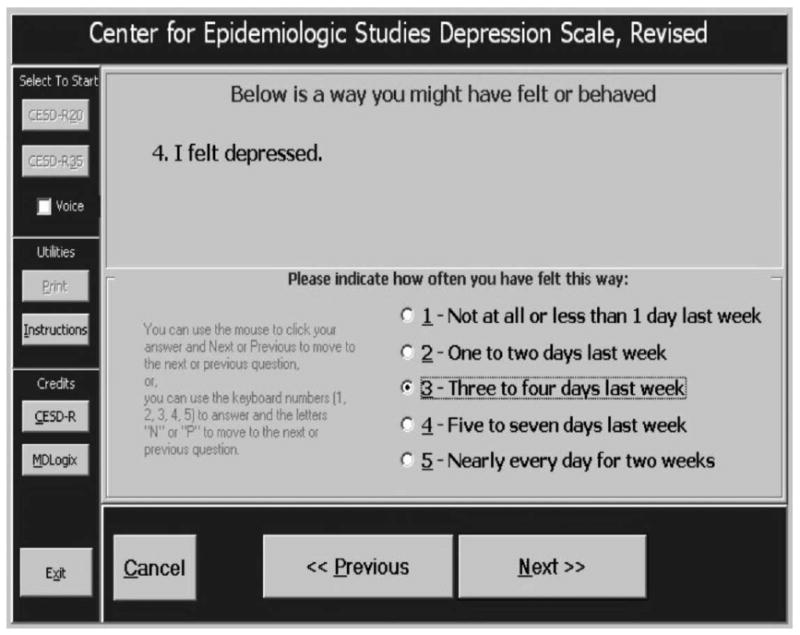

The CESD-R is a revised version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies of Depression Scale (CESD), a tool for self-report of depressive symptoms. It was revised by William W. Eaton, Professor in the Department of Mental Hygiene in the Johns Hopkins University School of Public Health [5]. The MDLogix computerized version of the CESD-R is a Windows program for self-report to determine risk for depression (Fig. 1). Subjects can take either the 20- or 35-item versions, and each version includes available digital audio of the questions and responses for persons with poor literacy or visual impairment. The self-report data can be stored on the local computer or transmitted over the Internet and stored on a server, for instance at a physician's office. The diagnostic and total and sub-scale score results and clinical recommendation are presented to the subjects each time after they complete the questionnaire. This report is printable, so it could be taken to a health care provider for further evaluation and treatment if indicated. Features of the MDLogix computerized CESD-R include: optional digital audio, 20-item short form, 35-item long form, DSM-IV-based diagnostic scoring, dimensional depression sub-scale scores, and summary printable graphic chart and clinical recommendations. The CESD-R client program is free, and can be downloaded from the MDLogix website (http://www.mdlogix.com).

Fig. 1.

Illustration of an example of an item from the computer application described in the text.

We implemented the computer application as a client-server system, using Microsoft NT Server 4.0 and SQL Server 7.0 running on a server and two client computers. Borland Delphi Client-Server 4.0 was used for programming the client computers. To limit difficulties caused by poor vision or literacy we developed and linked digitized audio files for all the text of the assessment interface. The voice reading this text was that of an older woman. The participant could turn the audio off or on as desired. When the audio is on, the participant can touch any panel on the interface to replay the audio for that text. Headphones with volume control were used to maintain privacy. To facilitate use of the assessment by older persons we used touch screens for test items and response choices.

2.2. Study sample

The study was carried out in a convenience sample of elderly of the Center for Primary Care at Good Samaritan Hospital in Baltimore. The practice has three physicians. The patient population is comprised of approximately 40% persons over the age of 65 years, 60% African–American, and 60% female. To be eligible for the study, participants needed to be aged 65 years and older and to have visited the doctor for outpatient care during the study period. Upon the recommendation of the clinic staff some patients were not approached for enrollment if the staff thought the patient would be unlikely to use a computer due to extreme fragility, poor cognitive status, or other factors. About 240 patients were approached for recruitment into the study.

2.3. Study design

The instruments employed were the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale, Revised (CESDR20, 20 items [5]; Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS15, 15 items) [6]; activities of daily living (ADL, four items) [7]; and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL, six items) [8]. All instruments were implemented in the computer system but were also assembled in paper form. An interviewer administered a separate questionnaire to assess patient experiences, attitudes, and comments about the computer.

2.4. Analytic strategy

The inter-method variation of the means of the results of all instruments at baseline and at 1-week retest follow-up were measured. Reliability comparisons were made by calculating the Pearson correlation coefficients measuring the correlation between all bivariate depression and function assessment measures. These included the test–retest reliability for both modes (computer and paper and pencil forms), the concurrent validity at each time point across modes of administration, and the predictive validity for computer at baseline and for paper at baseline. We also report descriptive analysis of the experiences, attitudes, and comments about the computer system from the users.

3. Results

3.1. Study sample

Out of the sample of 240 persons approached a total of 68 patients agreed to participate. We were unable to systematically ask the patients who refused about their reasons for refusal. We did, however, conversationally inquire, and also listened to their statements and concerns. Our impression was that most of the patients refusing did not want to do additional work that was not part of the clinic routine. One concern that many patients expressed was worry that they would miss seeing their doctor or that the doctors' time would somehow be reduced. Complete baseline data, both paper and computer assessments, were obtained on 54 patients, and 34 of these patients completed 1-week retest follow-up assessment. Of 54 participants, 35 were women and 42 self-identified their ethnicity as African–American.

3.2. Inter- and intra-method reliability

Descriptive statistics of the computer and paper versions of CESDR20, GDS15, ADL, and IADL are provided in Table 1. The CESDR20 inter-method variation of the means at baseline and at 1-week retest follow-up were less than 10%. In other words, the computer-administered baseline CESDR20 mean was within 10% of the paper-administered baseline CESDR20. Similarly, the GDS15, ADL, and IADL inter-method variation of the means at baseline and at 1-week retest were less than 5%.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for the computer and paper versions of instruments administered at baseline and at 1 week follow-up

| Baseline or follow-up | Mode of assessment | n | Mean | S.D. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CESDR20 | Baseline | Computer | 53 | 11.81 | 11.46 |

| Baseline | Paper | 54 | 10.76 | 14.65 | |

| Follow-up | Computer | 34 | 8.68 | 9.81 | |

| Follow-up | Paper | 37 | 9.35 | 13.24 | |

| GDS15 | Baseline | Computer | 51 | 17.88 | 2.41 |

| Baseline | Paper | 49 | 17.78 | 2.47 | |

| Follow-up | Computer | 33 | 17.15 | 2.66 | |

| Follow-up | Paper | 33 | 17.52 | 2.49 | |

| ADL | Baseline | Computer | 53 | 11.64 | 1.04 |

| Baseline | Paper | 54 | 11.61 | 1.37 | |

| Follow-up | Computer | 34 | 11.24 | 1.62 | |

| Follow-up | Paper | 36 | 11.56 | 1.34 | |

| IADL | Baseline | Computer | 51 | 14.92 | 2.76 |

| Baseline | Paper | 54 | 15.67 | 3.17 | |

| Follow-up | Computer | 34 | 15.59 | 2.64 | |

| Follow-up | Paper | 37 | 15.22 | 3.55 |

n, Number; S.D., standard deviation.

Table 2 provides the Pearson correlation coefficients for the computer and paper versions of the GDS15 and CESDR20 at baseline and follow-up assessments. The inter-method reliability of the GDS15 at baseline was good (0.719, n = 47), as was the intra-method reliability of the computer in time (0.697, n = 31). The correlation between the computer and paper versions of the CESDR20 at baseline was good (0.740, n = 53), and the correlation between the CESDR20 computer version at baseline and follow-up was high (0.849, n = 34). The correlation between the computer and paper versions of the CESDR20 at follow-up was not as high (0.605, n = 34), but still acceptable. The correlation between the baseline and follow-up administration of the paper CESDR20 was lower (0.615, n = 37) than that of the computerized version. Although the correlation of CESDR20 across time when administered by paper was still good, the computer CESDR20 appeared somewhat more stable over time than the paper version.

Table 2.

Pearson correlation coefficients for computer and paper administration of the Geriatric Scale and the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale, Revised (CESDR20) and for test–retest (mean test–retest interval of 1 week)

| Baseline computer | Baseline paper | Follow-up computer | Follow-up paper | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline computer | 0.740, n = 53 | 0.849, n = 34 | 0.637, n = 37 | |

| Baseline paper | 0.719, n = 47 | 0.616, n = 34 | 0.615, n = 37 | |

| Follow-up computer | 0.697, n = 31 | 0.789, n = 33 | 0.605, n = 34 | |

| Follow-up paper | 0.844, n = 31 | 0.709, n = 32 | 0.834, n = 30 |

Pearson correlation coefficients related to the GDS15 are shown in the lower left of the table while the upper right provides the Pearson correlation coefficients related to the CESDR20. n's represent number of persons in each cell. All correlation coefficients are significantly different from zero (P <0.05).

3.3. Experiences and attitudes

Few participants had experience with computers: 72% reported never having used a computer, and 90% said they did not have a computer in their home. Only 6% had ever used the Internet, and 94% had never used e-mail. The participants as a group did not express anxiety or frustration with computers in general (Table 3). Although 28% were anxious prior to using the computer testing system, that percent decreased to 19% after using the system. About half the patients (53%) said their feelings changed during the study, and comments suggest changes were for the better. Some participants were anxious and frustrated by the thought of using computers, but for most persons anxiety diminished with use.

Table 3.

Responses regarding attitudes about using the computer

| Item | n | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Agree | Strongly agree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Using computers makes me anxious | 30 | 23.3 | 46.7 | 26.7 | 3.3 |

| Having to use computers is frustrating | 30 | 16.7 | 53.3 | 20.0 | 10.0 |

| I like using computers | 31 | 3.2 | 32.3 | 51.6 | 12.9 |

| Having to use computers made me anxious before this study | 29 | 20.7 | 51.7 | 20.7 | 6.9 |

| Using the computer made me anxious while answering questions | 31 | 12.9 | 67.7 | 12.9 | 6.5 |

| I was comfortable using the computer | 32 | 0.0 | 9.4 | 75.0 | 15.6 |

| My feelings about computers changed during the study | 28 | 7.1 | 39.3 | 46.4 | 7.1 |

Numbers represent percent of person responding to the item with “strongly disagree”, “disagree”, “agree”, or “strongly agree”.

4. Discussion

We were encouraged by the results of the use of the software system for assessment of depression in older persons. The efficiency and reliability of computer assessment in comparison to the paper instruments were as good or better. Even though most patients had not ever used a computer prior to participating in the study, patients had generally favorable attitudes toward the use of computers, and also reported having a favorable experience with the computer testing system.

Before placing our results in the context of other investigations of computer applications in mental health care, the limitations of our work demand comment. First, the sample for this preliminary study was small. Second, we did not systematically ask about reasons for refusal to participate. As a result the non-participants are not well characterized. However, our impression was that most of the patients refusing did not want to do additional work that was not part of the clinic routine and were not refusing specifically to avoid using computers. Third, depression and functional assessments in this study were based on self-report, so there is the potential for sources of error associated with imperfect recall and response bias (e.g. socially desirable responding).

Experience with computers is not widespread among older people. Five percent of people older than 65 years use computers, compared with about 45% of young and middle-aged adults [9]. A recent study in primary care suggests 54.3% of patients have e-mail access [10]. The number of older patients with computer experience will increase in coming decades. Education level, previous experience with computers, and attitudes toward computers are related to successful patient–computer interaction [11]. Although most participants in our study had no previous computer experience patients generally had favorable attitudes toward computers. This finding supports other studies suggesting that electronic data-capture methods were preferred over traditional paper-and-pen methods by elderly volunteers and patients [12–14]. In our study computer anxiety reported by some patients before the assessment appeared to decrease with experience with the system. Computer administration resulted in scores that were highly correlated to paper and pencil testing and would seem to be a viable alternative. Computer-assisted interviews also resulted in highly stable results of questionnaires over a 1-week follow-up interval.

The care of depressive disorders may be our most useful barometer for the quality of mental health services in the primary care sector [15]. Older adults with depression commonly present to primary care physicians in the context of physical illness and not to specialists in mental health [16]. Physical illness and depression contribute to overall disability [17,18], but physicians may miss depression because of the competing demands of care [4]. Patients with depression may have medical illness or somatic complaints and may deny depression [19,20], making dealing with depression even more difficult. Among patients whom the physician has identified and is managing with depression, availability of a computerized assessment would facilitate follow-up care because change in depressive symptoms could be documented, complementing the clinical assessment. The computer-assisted interview may be viewed as any other clinical test for which we would send the patient for evaluation and follow-up.

Automated methods for collection of mental health data are needed that are easy, quick, inexpensive, and reliable and that can be integrated into practice routine. Computer-administered rating scales offer a reliable, inexpensive, accessible and time-efficient means of assessing psychiatric symptoms. Patients often find it easier to disclose sensitive information to a computer system, despite knowing that humans will see their answers, particularly regarding sexual behavior [21], HIV risk factors [22], and suicidal ideas [23,24]. Computer-assisted interviews for evaluation of depression, function and cognition can complement clinical activities and free clinicians to do what they do best—form a therapeutic relationship with patients.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by SNUF and FMW, Katholieke Universiteit Nijmegen, The Netherlands and an NIMH Small Business Innovation Research grant to Dr Tien (R43 MH56315). Data analysis was supported by an American Academy of Family Physicians Advanced Research Training Grant (Dr Bogner).

References

- 1.Strain JJ, Pincus HA, Gise LH, Houpt JL. The role of psychiatry in the training of primary care physicians. General Hospital Psychiatry. 1986;8:372–385. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(86)90053-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frasure-Smith N, Lesperance F, Talajic M. Depression following myocardial infarction: Impact on 6-month survival. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1993;270:1819–1825. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frasure-Smith N, Lesperance F, Talajic M. Depression and 18-month prognosis after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1995;91:999–1005. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.4.999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klinkman MS. Competing demands in psychosocial care: a model for the identification and treatment of depressive disorders in primary care. General Hospital Psychiatry. 1997;19:98–111. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(96)00145-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gallo JJ, Rabins PV. Depression without sadness: alternative presentations of depression in late life. American Family Physician. 1999;60:820–826. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yesavage JA, Brink TL. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1983;17:37–49. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(82)90033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, et al. Studies of illness in the aged: the index of ADL. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1963;185:914–919. doi: 10.1001/jama.1963.03060120024016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9:179–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.US Bureau of the Census. Use of computers at home, school, and work by persons 18 years and older. US Bureau of Census; Washington, DC: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Couchman RG, Forjuoh SN, Rascoe TG. E-mail communications in family practice. The Journal of Family Practice. 2001;50:414–418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spinhoven P. Feasibility of computerized psychological testing with psychiatric outpatients. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1993;49:440–447. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(199305)49:3<440::aid-jclp2270490320>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yarnold PR. Assessing functional status of elderly adults via microcomputer. Perceptual and Motor Skills. 1996;82:689–690. doi: 10.2466/pms.1996.82.2.689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drummond HE. Electronic Quality of life questionnaire: a comparison of pen-based electronic questionnaires with conventional paper in a gastrointestinal study. Quality of Life Research. 1995;4:21–26. doi: 10.1007/BF00434379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O'Connor KP. Evaluation of a computer interview system for use with neuro-otology patients. Otolaryngology. 1989;14:3–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2273.1989.tb00329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williams JW, Rost K, Dietrich AJ, Ciotti MC, Zyzanski SJ, Cornell J. Primary care physicians' approach to depressive disorders. Archives of Family Medicine. 1999;8:58–67. doi: 10.1001/archfami.8.1.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gallo JJ, Coyne JC. The challenge of depression in late life; bridging science and service in primary care, editorial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;284:1570–1572. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.12.1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alexopoulos GS. Geriatric depression in primary care, editorial. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 1996;11:397–400. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lyness J, et al. Depressive symptoms, medical illness, and functional status in depressed psychiatric inpatients. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1993;150:910–915. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.6.910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gallo JJ, Anthony JC, Muthen BO. Age differences in the symptoms of depression: a latent trait analysis. Journals of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences. 1994;49:251–264. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.6.p251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gallo JJ, Rabins PV, Anthony JC. Sadness in older persons: 13-year follow-up of a community sample in Baltimore, MD. Psychological Medicine. 1999;29:341–350. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798008083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kobak KA, Greist JH, Jefferson JW, Katzelnick DJ. Computer-administered clinical rating scales. A review, Psychopharmacology. 1996;127:291–301. doi: 10.1007/s002130050089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Locke SE, Kowaloff HB, Hoff RG, Safran C, Popovsky MA, Cotton DJ, et al. Computer-based interview for screening blood donors for risk of HIV transmission. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1992;268:1301–1305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Greist JH, Gustafson DH, Strauss FF, Rowse GL, Laughren TP, Chiles JA. Computer interview for suicide-risk prediction. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1973;130:1327–1332. doi: 10.1176/ajp.130.12.1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Petrie K, Abell W. Responses of parasuicides to a computerized interview. Computers in Human Behaviour. 1994;10:415–418. [Google Scholar]