Abstract

Background and Purpose

Left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) is a risk factor for cardiovascular events, but its effect on ischemic stroke risk is established mainly in whites. The effect of LV geometry on stroke risk has not been defined. The aim of the present study was to evaluate whether LVH and LV geometry are independently associated with increased ischemic stroke risk in a multiethnic population.

Methods

A population-based case-control study was conducted on 394 patients with first ischemic stroke and 413 age-, sex-, and race-ethnicity–matched community control subjects. LV mass was measured by transthoracic echocardiography. LV geometric patterns (normal, concentric remodeling, concentric or eccentric hypertrophy) were identified. Stroke risk associated with LVH and different LV geometric patterns was assessed by conditional logistic regression analysis in the overall group and age, sex, and race-ethnic strata, with adjustment for established stroke risk factors.

Results

Concentric hypertrophy carried the greatest stroke risk (adjusted odds ratio [OR], 3.5; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.0 to 6.2), followed by eccentric hypertrophy (adjusted OR, 2.4; 95% CI, 2.0 to 4.3). Concentric remodeling carried slightly increased stroke risk (adjusted OR, 1.7; 95% CI, 1.0 to 2.9). Increased LV relative wall thickness was independently associated with stroke after adjustment for LV mass (OR, 1.6; 95% CI, 1.1 to 2.3).

Conclusions

LVH and abnormal LV geometry are independently associated with increased stroke risk. LVH is strongly associated with ischemic stroke in all age, sex, and race-ethnic subgroups. Increased LV relative wall thickness imparts an increased stroke risk after adjustment for LV mass and is of additional value in stroke risk prediction.

Keywords: echocardiography, heart ventricle, hypertrophy, left ventricular, stroke

Left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH), or increased LV mass, is a risk factor for cardiovascular diseases.1–9 Echocardiographic LVH is associated with cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, as well as all-cause mortality.4–9 The risk increase is independent of other cardiovascular risk factors, including arterial hypertension.4–6,8,9 Recently, there have been reports of incremental risk associated with abnormal LV geometry beyond the simple LV mass increase. From LV mass and relative wall thickness (RWT), 3 abnormal geometric patterns—concentric hypertrophy, eccentric hypertrophy, and concentric remodeling10—are identified that appear to carry different risks for cardiovascular events. Concentric hypertrophy (increase in both LV mass and RWT) carries the highest risk,4,11 followed by eccentric hypertrophy (increased LV mass, normal RWT4,11). The independent risk of an isolated RWT increase (concentric remodeling) is controversial.11–14

LVH is also independently associated with risk of ischemic stroke.15–20 This association, identified in ECG studies,14–17 was confirmed with more sensitive echocardiographic techniques.19,20 Increased stroke risk was shown mainly in whites,15–19 with fewer data available in blacks13,20 and Hispanics.21 The role of abnormal LV geometry in stroke risk has received little attention. In hypertensive patients, concentric and eccentric hypertrophy was associated with an ≈2-fold increase in stroke incidence, whereas concentric remodeling did not carry increased risk.4 However, the small number of strokes precluded definitive conclusions in this and similar studies.4,13

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the role of LVH and abnormal LV geometry as independent risk factors for ischemic stroke in the multiethnic population of the Northern Manhattan Stroke Study (NOMASS).

Methods

Study Population

Subjects were drawn from NOMASS, a community-based epidemiological study that evaluates stroke incidence, risk factors, and prognosis in northern Manhattan. Recruitment modalities have been published previously.21,22 Briefly, patients >39 years of age residing in northern Manhattan who were admitted at the Presbyterian Hospital with a first ischemic stroke were eligible. The race-ethnic distribution in this community is ≈20% black, 63% Caribbean Hispanic, and 15% white residents. Race-ethnicity was defined by self-identification in response to a questionnaire modeled after the US census. Stroke-free subjects were identified by random-digit dialing of northern Manhattan households. Control subjects were matched to cases by age (within 5 years), sex, and race-ethnicity.

From May 1993 through December 1998, 431 patients with first ischemic stroke and 434 stroke-free control subjects underwent 2-dimensional transthoracic echocardiography. All necessary echocardiographic measurements were obtainable in 394 stroke patients (91.4%) and in 413 control subjects (95.2%). Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center.

Diagnostic Evaluation

Stroke risk factors were collected by direct interview or medical record review. Arterial hypertension was defined by history or antihypertensive treatment or by blood pressure >140/90 mm Hg (average of 2 measurements). Hypercholesterolemia was defined as total serum cholesterol >240 mg/dL or the presence of appropriate treatment. Diabetes mellitus was defined as abnormal fasting blood sugar, positive history, or presence of oral or insulin treatment. Coronary artery disease included history of myocardial infarction or typical angina, a positive diagnostic test (stress test, coronary angiography), or appropriate treatment. Atrial fibrillation was documented on a current or past ECG or Holter monitoring. Congestive heart failure was diagnosed on the basis of clinical signs, symptoms, and/or appropriate medical treatment.

Neurological workup in stroke patients included head CT or MRI, carotid and vertebral artery duplex Doppler ultrasonography, and transcranial Doppler examination of the middle and anterior cerebral arteries or basilar artery.

Echocardiographic Evaluation

Transthoracic echocardiography was performed according to the guidelines of the American Society of Echocardiography23 with Hewlett-Packard Sonos 1000 and 2500 ultrasound equipment (Hewlett-Packard Imaging Systems Division).

LV end-diastolic diameter (LVDD), LV end-systolic diameter (LVSD), interventricular septum (IVS), and posterior wall (PW) thickness at end diastole were measured. LV mass (LVM) was calculated from the corrected American Society of Echocardiography method24: LVM=0.8(1.04[(IVS+LVDD+PW)3−LVDD3]+ 0.6).

LV mass (log transformed to increase normality) was then regressed on height and sex. LVH was defined as adjusted LV mass greater than the 90th percentile of the control subjects without conditions associated with LVH such as arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, obesity, and cardiovascular diseases. RWT was calculated according to this formula10: 2(PW/LVDD).

The 90th percentile of the control population described above (RWT: 0.60 for women, 0.54 for men) was used as the upper limit of normal. Four LV geometric patterns10 were identified on the basis of LV mass and RWT: normal (normal LV mass, normal RWT), concentric remodeling (normal LV mass, abnormal RWT), eccentric hypertrophy (abnormal LV mass, normal RWT), and concentric hypertrophy (abnormal LV mass, abnormal RWT).

Echocardiographic studies were interpreted by researchers blinded to case-control status and other clinical characteristics. Interobserver variability for the variables measured ranged between 8% and 10%.

Statistical Analysis

Data are reported as mean±SD for continuous variables and as frequency for categorical variables. Differences between proportions were assessed by χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test; differences between mean values, by unpaired Student’s t test. A 2-tailed value of P<0.05 was considered significant.

Univariate and multivariate conditional logistic regression analyses (PROC PHREG, SAS 8.2) were used to test the association between LVH/geometric patterns and ischemic stroke. Unadjusted odds ratios (ORs) were calculated for the entire study group and age, sex, and race-ethnic subgroups. Multivariate analysis was used to determine the adjusted OR for stroke of LVH and each LV geometric pattern after adjustment for variables significantly associated with ischemic stroke by univariate analysis (arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, atrial fibrillation, coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure). Adjusted ORs and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated.

To assess the effect of age (41 to 59, ≥60 years), sex, and race-ethnicity on the association between LVH/geometric patterns and stroke, separate variables were fit in the model to quantify the effect of LVH/geometric patterns independently for each strata. Differences between strata were tested with Wald’s χ2.

To assess the effect of RWT above that of LV mass on stroke risk, multivariate analysis was performed after adjustment for LV mass as a continuous variable and for other stroke risk factors described above.

Results

Demographics of the study population are shown in Table 1. Interracial differences existed in traditional stroke risk factors (Table 2).

TABLE 1.

Demographics of the Study Group

| Stroke Patients (n=394) |

Control Subjects (n=413) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age* | Men/Women | Age* | Men/Women | |

| Overall group | 68.6±12.2 | 183/211 | 68.3±11.5 | 185/228 |

| Whites | 75.2±12.8 | 35/32 | 74.5±11.1 | 37/33 |

| Blacks | 69.4±10.6 | 38/71 | 69.9±10.5 | 41/75 |

| Hispanics | 66.3±12.0 | 105/107 | 65.6±11.3 | 102/119 |

Mean±SD.

TABLE 2.

Stroke Risk Factors Distribution in the Entire Study Group and by Race-Ethnicity

| Entire Group |

Whites |

Blacks |

Hispanics |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases, % |

Controls, % |

P | Cases (n=67), % |

Controls (n=70), % |

P | Cases (n=109), % |

Controls (n=116), % |

P | Cases (n=212), % |

Controls (n=221), % |

P | |

| Arterial hypertension | 78 | 67 | 0.001 | 70 | 54 | 0.06 | 82 | 61 | 0.05 | 79 | 70 | 0.03 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 31 | 16 | 0.001 | 16 | 9 | 0.2 | 34 | 11 | 0.001 | 34 | 21 | 0.002 |

| Cigarette smoking | 20 | 16 | 0.2 | 5 | 13 | 0.09 | 35 | 20 | 0.01 | 16 | 15 | 0.6 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 36 | 42 | 0.1 | 26 | 40 | 0.08 | 36 | 43 | 0.3 | 40 | 43 | 0.6 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 10 | 2 | 0.001 | 21 | 3 | 0.001 | 8 | 4 | 0.1 | 8 | 1 | 0.001 |

| CAD | 35 | 20 | 0.001 | 54 | 29 | 0.003 | 26 | 17 | 0.1 | 34 | 20 | 0.001 |

| CHF | 12 | 5 | 0.001 | 15 | 1 | 0.004 | 6 | 3 | 0.3 | 15 | 8 | 0.02 |

CAD indicates coronary artery disease; CHF, congestive heart failure.

LVH, LV Geometry, and Risk of Ischemic Stroke

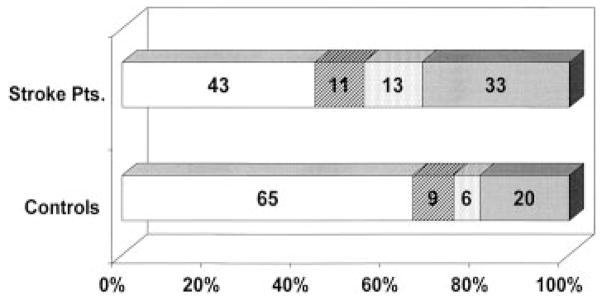

The distribution of LV geometric patterns is summarized in the Figure. Normal pattern was more frequent in control subjects than in stroke patients (65% versus 43%; P=0.0001). Stroke patients had significantly higher frequencies of concentric hypertrophy (13% versus 6%; P=0.0001) and eccentric hypertrophy (33% versus 20%; P=0.0001). Arterial hypertension frequency and duration and blood pressure values are listed in Table 3. Blood pressure was significantly higher in abnormal geometry compared with normal geometry groups (P<0.01). Hypertension duration was longest in the concentric hypertrophy group, but not significantly (P=0.1). Of patients with LVH, 15% had no diagnosis of hypertension.

LV geometric patterns in the study population. □ Indicates normal;  , concentric remodeling;

, concentric remodeling;  , concentric hypertrophy; and

, concentric hypertrophy; and  , eccentric hypertrophy.

, eccentric hypertrophy.

TABLE 3.

Prevalence and Duration of Hypertension and Blood Pressure Values in Different Geometric Patterns

| Normal |

Concentric Hypertrophy |

Eccentric Hypertrophy |

Concentric Remodeling |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | Controls | Cases | Controls | Cases | Controls | Cases | Controls | |

| Prevalence of hypertension, % | 68.5 | 59.3 | 86.5 | 75.0 | 84.1 | 86.3 | 85.7 | 76.9 |

| Hypertension duration, y* | 10.9±10.6 | 12.7±13.5 | 15.8±15.3 | 18.7±17.0 | 14.4±12.3 | 12.0±10.4 | 13.7313.0 | 12.0±7.8 |

| SBP, mm Hg | 139.6±16.7 | 138.6±20.7 | 150.9±22.7 | 153.2±28.7 | 144.8±20.1 | 153.4±22.8 | 148.9322.4 | 144.2±21.8 |

| DBP, mm Hg | 80.7±10.4 | 81.7±11.2 | 86.1±13.2 | 86.0±13.3 | 84.2±11.3 | 84.7±12.6 | 85.0315.1 | 86.2±11.1 |

SBP indicates systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure.

Mean±SD.

LVH was associated with increased stroke risk (adjusted OR, 2.5; 95% CI, 1.7 to 3.5; Table 4). This was observed in all age, sex, and race-ethnic strata. No significant interaction between LVH and arterial hypertension or other stroke risk factors on stroke risk was found.

TABLE 4.

Association Between LV Hypertrophy and Ischemic Stroke

| LVH |

||

|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR* (95% CI) | |

| Entire group | 2.9 (2.1–4.1) | 2.5 (1.7–3.5) |

| Men | 3.3 (2.0–5.5) | 2.8 (1.7–4.9) |

| Women | 2.6 (1.7–4.1) | 2.2 (1.4–3.6) |

| Age 41–59 y | 3.5 (1.8–7.1) | 2.9 (1.4–6.0) |

| Age ≥60 y | 2.7 (1.9–4.0) | 2.4 (1.6–3.5) |

| White | 5.3 (2.0–13.8) | 4.6 (1.7–12.2) |

| Black | 2.4 (1.3–4.3) | 2.1 (1.1–4.0) |

| Hispanic | 2.8 (1.7–4.3) | 2.3 (1.4–3.8) |

Adjusted for arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, atrial fibrillation, coronary artery disease, and congestive heart failure.

Concentric hypertrophy carried the greatest stroke risk (Table 5), followed by eccentric hypertrophy. Concentric remodeling was associated with a modest risk increase. Increase in risk was independent of the presence of arterial hypertension and other risk factors.

TABLE 5.

Association Between LV Geometric Patterns and Ischemic Stroke

| Concentric Hypertrophy |

Eccentric Hypertrophy |

Concentric Remodeling |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR* (95% CI) | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR* (95% CI) | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR* (95% CI) | |

| Entire group | 3.8 (2.2–6.5) | 3.5 (2.0–6.2) | 2.9 (2.0–4.3) | 2.4 (1.6–3.7) | 1.7 (1.0–2.8) | 1.7 (1.0–2.9) |

| Men | 3.9 (1.7–8.9) | 4.3 (1.8–10) | 3.4 (1.9–6.0) | 2.7 (1.4–5.0) | 1.5 (0.7–2.9) | 1.6 (0.8–3.3) |

| Women | 3.6 (1.8–7.5) | 2.9 (1.4–6.3) | 2.7 (1.7–4.4) | 2.3 (1.3–3.8) | 2.0 (1.0–4.1) | 1.8 (0.9–3.8) |

| Age 41–59 y | 5.8 (1.2–27) | 6.0 (1.2–31) | 3.2 (1.5–6.7) | 2.5 (1.1–5.4) | 1.5 (0.4–5.4) | 1.6 (0.4–5.9) |

| Age ≥60 y | 3.5 (1.9–6.4) | 3.2 (1.7–6.0) | 2.9 (1.9–4.4) | 2.4 (1.5–3.9) | 1.7 (1.0–2.9) | 1.5 (0.8–2.7) |

| White | 4.0 (0.7–21) | 4.0 (0.8–20) | 6.1 (2.2–17) | 5.0 (1.7–15) | 2.0 (0.5–8.2) | 2.2 (0.4–11) |

| Black | 2.5 (1.1–6.1) | 2.5 (1.0–6.2) | 2.3 (1.1–4.8) | 2.0 (0.9–4.4) | 1.2 (0.5–2.7) | 1.2 (0.5–2.8) |

| Hispanic | 4.8 (2.2–10) | 4.3 (1.9–9.8) | 2.8 (1.7–4.6) | 2.3 (1.3–4.0) | 2.0 (1.0–4.0) | 2.0 (1.0–4.1) |

All comparisons were with normal LV geometry.

Adjusted for arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, atrial fibrillation, coronary artery disease, and congestive heart failure.

Effect of Age, Sex, and Race-Ethnicity

Concentric and eccentric hypertrophy was associated with ischemic stroke across all sex and age strata, with adjusted ORs ranging from 2.3 to 6.0 (Table 5). Concentric remodeling was not associated with increased stroke risk in any subgroup.

The effect of concentric hypertrophy on stroke risk appeared stronger in Hispanics (adjusted OR, 4.3; 95% CI, 1.9 to 9.8), although differences were not statistically significant (Hispanics versus blacks, P=0.37; Hispanics versus whites, P=0.93). Eccentric hypertrophy was associated with stroke in whites and Hispanics but less so in blacks. Interracial differences were not statistically significant (whites versus blacks, P=0.18; Hispanics versus blacks, P=0.76). Concentric remodeling was not associated with an increased stroke risk in any race-ethnic subgroups.

RWT and Risk of Stroke

After adjustment for LV mass as a continuous variable, abnormal RWT was found to significantly increase stroke risk in both univariate (OR, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.03 to 2.2) and multivariate (OR, 1.6; 95% CI, 1.1 to 2.3) analyses. No interaction on stroke risk was detected between RWT and LV mass (P=0.47 unadjusted, P=0.68 adjusted).

Geometric Patterns and Stroke Subtype

Of 392 strokes, 65 (16.6%) were large-vessel disease, 91 (23.2%) were lacunar, 72 (18.4%) were cardioembolic, 13 (3.3%) were other mechanisms, and 151 (38.5%) were cryptogenic. Concentric LVH tended to have more lacunar (32.7%) and fewer cryptogenic (23.1%) strokes than other geometries. Eccentric hypertrophy was associated with a slight excess of cardioembolic strokes (26.5%), as was concentric remodeling for lacunar strokes (26.2%).

Discussion

LVH and Stroke Risk

LVH is an established risk factor for cardiovascular diseases1–9 and ischemic stroke, the latter demonstrated mainly in whites.15–19 Fewer data are available in black populations, mainly regarding the combined end point of cardiovascular events and stroke.13,20 Little information is available in Hispanics, especially of Caribbean origin.21 In our study, LVH was associated with a 2.5-fold increase in stroke risk after adjustment for other stroke risk factors. LVH was independently associated with stroke across all the race-ethnic subgroups studied, suggesting that its effect on stroke risk may be similar across races, even in the presence of different stroke risk factors profiles.

The mechanisms of the association between LVH and ischemic stroke are not clear. LVH might be a marker of subclinical disease25 or predispose to other conditions directly involved in stroke etiology. LV mass correlates with carotid wall thickness and luminal diameter26,27 and predicts carotid atherosclerosis.28,29 LVH has been linked to cerebrovascular disease in blacks30 and predisposes to developing hypertension31 and atrial fibrillation.32 Alternatively, LVH could represent a time-integrated indicator of exposure to other risk factors33 such as hypertension and obesity, which affect the risk of stroke and cardiovascular disease.

LV Geometry and Stroke Risk

The value of LV geometry in the prediction of cardiovascular risk is controversial.11,12,14 Moreover, its role as a risk factor for ischemic stroke has been minimally investigated. We demonstrate that abnormal LV geometry is associated with an increased ischemic stroke risk and that RWT adds information not contained in LV mass. Although RWT per se did not increase stroke risk to a significant extent, it did so after adjustment for LV mass. This suggests that LV geometry may contribute to stroke in ways not necessarily related to LV mass. Determination of RWT may be useful for further stroke risk stratification, especially among patients with LVH.

The observation that abnormal LV geometry may affect stroke risk has precedents in the literature. Asymptomatic lacunar lesions are more frequent in patients with abnormal LV geometry, and both LV mass and RWT predict them.34 Arterial structure and function are abnormal in patients with concentric LVH35 and may partly explain its excess morbidity. Neurohormonal changes such as aldosterone and atrial natriuretic peptide elevation are associated with abnormal LV geometry36 and might be involved in both its development and its adverse prognostic effect. In our study, increased RWT tended to be more frequently associated with lacunar infarcts, suggesting a possible role of RWT as a marker of small-vessel disease. Cryptogenic stroke was less frequent in patients with concentric hypertrophy, which may be a marker of more extensive cardiovascular disease, leading to development of identifiable sources for stroke. Eccentric hypertrophy tended to be associated with cardioembolism, suggesting a role for LV dilatation as a possible embolic source. Further studies are needed to elucidate the complex relationship between LV mass, LV geometry, and stroke and potential strategies for decreasing stroke risk.

Study Strengths and Limitations

This is the first study to address the effect of LV mass and geometry on ischemic stroke risk in a community-based multiethnic population and in age, sex, and race-ethnic subgroups. Furthermore, it provides data on Hispanics of Caribbean origin, information that is scarce in the literature.

The case-control design has limitations, including potential selection bias. This bias was minimized by recruitment of cases and controls from the same community, randomization of control subject selection, and individual case-control matching. However, differences between cases and controls may have existed in variables not measured. Moreover, the study did not have power to address the association between LV mass and geometry and different stroke subtypes, and its power for detecting interracial differences was suboptimal. Finally, definitions of race-ethnicity are problematic because ethnicity is heterogeneous and its categorization may lead to assumptions of biological differences while masking other differences, such as cultural and socioeconomic variables, which may affect disease.

Clinical Implications

Our data suggest that assessment of LV mass and RWT should be included in stroke risk evaluation. Treatment is available to promote regression of LVH, possibly associated with reduction in the incidence of cardiovascular events, including stroke.37 Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors were shown to decrease RWT in hypertensive patients even in the absence of LVH.38 The possibility that pharmacological treatment affecting LV mass and geometry may also reduce the risk of ischemic stroke deserves further investigation.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported in part by grants from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (R01 NS29993, ROI NS33248, T32 NS07153). Dr Di Tullio is the recipient of a Mid-Career Award in Patient-Oriented Research by the National Institutes of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (K24 NS02241). We gratefully acknowledge the support of J.P. Mohr, MD, Director of Cerebrovascular Research. We also wish to thank Bernadette Boden-Albala, PhD, for her assistance in the preparation of the manuscript; Drs Renee Weslow, Maria Teresa Savoia, Tamanna Nahar, and Rui Liu for the interpretation of the echocardiographic studies; and Lynette M. De Los Santos, BS, Inna Titova, BS, and Gabrielle Gaspard, BS, for their assistance in the collection of the data.

References

- 1.Kannel WB, Gordon T, Castelli WP, Margolis JR. Electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy and risk of coronary heart disease: the Framingham study. Ann Intern Med. 1970;72:813–822. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-72-6-813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kannel WB. Prevalence and natural history of electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy. Am J Med. 1983;75:4–11. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(83)90111-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kannel WB, Dannenberg AL, Levy D. Population implications of electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy. Am J Cardiol. 1987;60:85I–93I. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(87)90466-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levy D, Garrison RJ, Savage DD, Kannel WB, Castelli WP. Prognostic implications of echocardiographically determined left ventricular mass in the Framingham Heart Study. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:1561–1566. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199005313222203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koren MJ, Devereux RB, Casale PN, Savage DD, Laragh JH. Relation of left ventricular mass and geometry to morbidity and mortality in uncomplicated essential hypertension. Ann Intern Med. 1991;114:345–352. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-114-5-345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ghali JK, Liao Y, Simmons B, Castaner A, Cao G, Cooper RS. The prognostic role of left ventricular hypertrophy in patients with or without coronary artery disease. Ann Intern Med. 1992;117:831–836. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-117-10-831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liao Y, Cooper RS, Durazo-Arvizu R, Mensah GA, Ghali JK. Prediction of mortality risk by different methods of indexation for left ventricular mass. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;29:641–647. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(96)00552-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haider AW, Larson MG, Benjamin EJ, Levy D. Increased left ventricular mass and hypertrophy are associated with increased risk for sudden death. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;32:1454–1459. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00407-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schillaci G, Verdecchia P, Porcellati G, Cuccurullo O, Cosco C, Perticone F. Continuous relation between left ventricular mass and cardiovascular risk in essential hypertension. Hypertension. 2000;35:580–586. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.35.2.580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ganau A, Devereux RB, Roman MJ, De Simone G, Pickering TG, Saba PS, Vargiu P, Simongini I, Laragh JH. Patterns of left ventricular hypertrophy and geometric remodeling in essential hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1992;19:1550–1558. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(92)90617-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krumholz HM, Larson M, Levy D. Prognosis of left ventricular geometric patterns in the Framingham Heart Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;25:879–884. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(94)00473-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Verdecchia P, Schillaci G, Borgioni C, Ciucci A, Battistelli M, Santucci A, Santucci C, Reboldi G, Porcellati C. Adverse prognostic significance of concentric remodeling of the left ventricle in hypertensive patients with normal left ventricular mass. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;25:871–878. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(94)00424-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gardin JM, McClelland R, Kitzman D, Lima JA, Bommer W, Klopfenstein HS, Wong ND, Smith VE, Gottdiener J. M-mode echocardiographic predictors of six- to seven-year incidence of coronary artery disease, stroke, congestive heart failure, and mortality in an elderly cohort (the Cardiovascular Health Study) Am J Cardiol. 2001;87:1051–1057. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(01)01460-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ghali JK, Liao Y, Cooper RS. Influence of left ventricular geometric patterns on prognosis in patients with or without coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;31:1635–1640. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00131-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Welin L, Svardsudd K, Wilhelmsen L, Larsson B, Tibblin G. Analysis of risk factors for stroke in a cohort of men born in 1913. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:521–526. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198708273170901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stokes J, Kannel WB, Wolf PA, D’Agostino RB, Cupples A. Blood pressure as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease: the Framingham study: 30 years of follow-up. Hypertension. 1989;13(suppl I):I-13–I-18. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.13.5_suppl.i13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shaper AG, Phillips AN, Pocock SJ, Walker M, MacFarlane PW. Risk factors for stroke in middle aged British men. BMJ. 1991;302:1111–1115. doi: 10.1136/bmj.302.6785.1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dutch TIA Trial Study Group. Predictors of major vascular events in patients with a transient ischemic attack or nondisabling stroke. Stroke. 1993;24:527–531. doi: 10.1161/01.str.24.4.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bikkina M, Levy D, Evans JC, Larson MG, Benjamin EJ, Wolf PA, Castelli WP. Left ventricular mass and risk of stroke in an elderly cohort: the Framingham Heart Study. JAMA. 1994;272:33–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liao Y, Cooper RS, McGee DL, Mensah GA, Ghali JK. The relative effects of left ventricular hypertrophy, coronary artery disease, and ventricular dysfunction on survival among black adults. JAMA. 1995;273:1592–1597. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rodriguez CR, Sacco RL, Sciacca RR, Boden-Albala B, Homma S, Di Tullio M. Physical activity attenuates the effect of increased left ventricular mass on the risk of ischemic stroke: the Northern Manhattan Stroke Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:1482–1488. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)01799-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Di Tullio MR, Sacco RL, Sciacca RR, Homma S. Left atrial size and the risk of ischemic stroke in an ethnically mixed population. Stroke. 1999;30:2019–2024. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.10.2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sahn DJ, DeMaria A, Kisslo J, Weyman A. Recommendations regarding quantitation in M-mode echocardiography: results of a survey of echocardiographic measurements. Circulation. 1978;58:1072–1083. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.58.6.1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Devereaux RB, Alonso DR, Lutas EM, Gottlieb GJ, Campo E, Sachs I, Reichek N. Echocardiographic assessment of left ventricular hypertrophy: comparison to necropsy findings. Am J Cardiol. 1986;57:450–458. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(86)90771-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Devereaux RB, Alderman MH. Role of preclinical cardiovascular disease in the evolution from risk factor exposure to development of morbid events. Circulation. 1993;88(pt 1):1444–1455. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.4.1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roman MJ, Saba PS, Pini R, Spitzer M, Pickering TG, Rosen S, Alderman MH, Devereaux RB. Parallel cardiac and vascular adaptation in hypertension. Circulation. 1992;86:1909–1918. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.86.6.1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kronmal RA, Smith VE, O’Leary DH, Polak JF, Gardin JM, Manolio TA. Carotid artery measures are strongly associated with left ventricular mass in older adults (a report from the Cardiovascular Heart Study) Am J Cardiol. 1996;77:628–633. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(97)89319-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Okin PM, Devereaux RB, Kligfield P. Association of carotid atherosclerosis with electrocardiographic myocardial ischemia and left ventricular hypertrophy. Hypertension. 1996;28:3–7. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.28.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roman MJ, Pickering TJ, Schwartz JE, Pini R, Devereaux RB. Association of carotid atherosclerosis and left ventricular hypertrophy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;25:83–90. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(94)00316-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Benjamin EJ, McNamara RL, Ding J, Arnett DK, Liebson PR, Tyroler HA, Cooper LS, Taylor H, Hutchinson RG, Skelton TN. Left ventricular mass and prevalent MRI cerebrovascular disease in an African-American cohort: the ARIC Study. Circulation. 2000;102(suppl II):II-586. Abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Post WS, Larson MG, Levy D. Impact of left ventricular structure on the incidence of hypertension: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 1994;90:179–185. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.90.1.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Varazi SM, Larson MG, Benjamin EJ, Levy D. Echocardiographic predictors of nonrheumatic atrial fibrillation: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 1994;89:724–730. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.89.2.724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Benjamin EJ, Levy D. Why is left ventricular hypertrophy so predictive of morbidity and mortality? Am J Med Sci. 1999;317:168–175. doi: 10.1097/00000441-199903000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kohara K, Zhao B, Jiang Y, Takata Y, Fukuoka T, Igase M, Miki T, Hiwada K. Relation of left ventricular hypertrophy and geometry to asymptomatic cerebrovascular damage in essential hypertension. Am J Cardiol. 1999;83:367–370. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(98)00870-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roman MJ, Pickering TG, Schwarz JE, Pini R, Devereaux RB. Relation of arterial structure and function to left ventricular geometric patterns in hypertensive adults. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;28:751–756. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(96)00225-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Muscholl MW, Schunkert H, Muders F, Elsner D, Kuch B, Hense HW, Riegger GA. Neurohormonal activity and left ventricular geometry in patients with essential arterial hypertension. Am Heart J. 1998;135:58–66. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(98)70343-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Verdecchia P, Schillaci G, Borgioni C, Ciucci A, Gattobigio R, Zampi I, Reboldi G, Porcellati C. Prognostic significance of serial changes in left ventricular mass in essential hypertension. Circulation. 1998;97:48–54. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.1.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.De Castro S, Pelliccia F, Cartoni D, Funaro S, Melillo G, Beni S, Magni G, Migliau G, Fedele F. Effects of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition on left ventricular geometric patterns in patients with essential hypertension. J Clin Pharmacol. 1996;36:1141–1148. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1996.tb04168.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]