Abstract

Amyloid-β (Aβ) peptides, widely presumed to cause Alzheimer’s disease, increased mouse neuronal expression of collagen VI through a mechanism involving transforming growth factor signaling. Reduction of collagen VI augmented Aβ neurotoxicity, whereas treatment of neurons with soluble collagen VI blocked the association of Aβ oligomers with neurons, enhanced Aβ aggregation and prevented neurotoxicity. These results identify collagen VI as an important component of the neuronal injury response and demonstrate its neuroprotective potential.

Introduction

Amyloid-β (Aβ) peptides are important in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. They are derived from amyloid precursor proteins (APP) and can self-aggregate into fibrillar and nonfibrillar structures. In transgenic mice with neuronal expression of familial Alzheimer’s disease–mutant human APP (hAPP) and high Aβ levels, memory deficits and neuronal dysfunction are most directly related to soluble Aβ1–42 (Aβ42) oligomers1. Many molecular alterations that correlate with memory deficits in these models are most prominent in the dentate gyrus, which is critical for learning and memory and shows early synaptic deficits in Alzheimer’s disease2.

We profiled Aβ-induced gene-expression changes in the dentate gyrus of hAPP transgenic mice and nontransgenic controls by DNA microarray analysis. All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of California, San Francisco. Expression of mRNA encoding the α1 subunit of collagen VI (Col6a1) was markedly increased in hAPP mice (data not shown). Collagen VI is a large triple-helix extracellular matrix (ECM) protein consisting of α1(VI), α2(VI) and α3(VI) subunits. Various forms of collagen have well-established roles in peripheral organs, but little is known about their functions in the brain. We are unaware of reports demonstrating activities of neuronal collagen VI.

We analyzed hippocampal Col6a1 expression in nontransgenic and hAPP mice (lines J20 (refs. 1,3) and J9 (ref. 4)) and humans with or without Alzheimer’s disease by quantitative RT-PCR and western blotting. At 3–6 months of age, Col6a1 mRNA and α1(VI) protein levels in dentate gyrus were higher in hAPP-J20 mice than in nontransgenic controls (Fig. 1a,b). Additional hAPP-J20 mice, aged 2–18 months, also had higher hippocampal levels of Col6a1 mRNA (Supplementary Fig. 1 online). In hAPP-J9 mice, which express about half as much hAPP/Aβ as hAPP-J20 mice4, hippocampal Col6a1 mRNA levels were elevated, but to a lesser extent (Supplementary Fig. 1). In humans, Col6a1 mRNA levels in dentate gyrus were higher in individuals with Alzheimer’s disease than in nondemented controls (Fig. 1c). Humans with Alzheimer’s disease and hAPP-J20 mice also showed higher dentate levels of Col6a2 mRNA and a trend toward increased expression of Col6a3 (Supplementary Fig. 1).

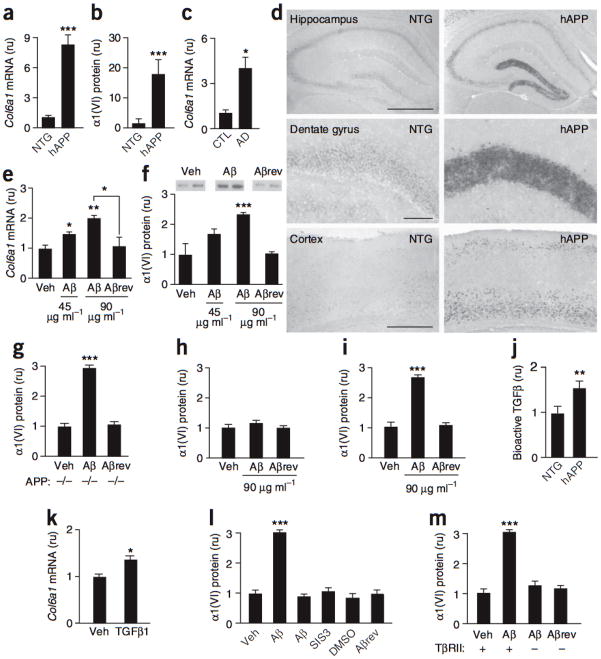

Figure 1. Aβ increases neuronal expression of the collagen VI α1 subunit through mechanisms involving TGFbold β signaling.

(a–c) Dentate gyrus Col6a1 mRNA (a) and α1(VI) protein (b) levels in nontransgenic (NTG) and hAPP-J20 mice (n= 11–13 per group, aged 3–6 months) and dentate gyrus Col6a1 mRNA levels (c) in nondemented humans (CTL, n = 3) and individuals with Alzheimer’s disease (AD, n = 8) (Supplementary Methods and Supplementary Fig. 3 online). The mean Col6a1/Gapdh mRNA, α1(VI)/tubulin and Col6a1/NSE mRNA ratios in nontransgenic or CTL samples (a–c) were defined as 1. (d) In situ hybridization of coronal mouse brain sections with a Col6a1-specific antisense riboprobe. Scale bars represent 500 μm. (e,f) Primary cultures of purified neocortical/hippocampal neurons of nontransgenic mice treated for 24 h with vehicle (Veh), Aβ or Aβrev (45 or 90 μg ml−1). Col6a1 mRNA levels in cell lysates (e) and α1(VI) protein levels in medium (f, representative western blot signals above). The average Col6a1/Gapdh mRNA and α1(VI)/tubulin protein ratios in vehicle-treated cultures were defined as 1. (g) α1(VI) protein levels in medium of neuronal cultures from APP-deficient mice treated for 24 h with vehicle, Aβ42 (90 μg ml−1) or Aβrev (90 μg ml−1). (h,i) α1(VI) protein levels in medium of nontransgenic cultures of mouse astrocytes (h) or neurons and astrocytes (i) treated with vehicle, Aβ42 or Aβrev for 24 h. (j) Hippocampal levels of bioactive TGFβ in 6–7-month-old nontransgenic (n = 7) and hAPP-J20 (n = 5) mice, measured by bioassay. (k) Col6a1 mRNA levels in nontransgenic neuronal cultures treated with vehicle or bioactive TGFβ1 (10 nM) for 24 h. (l) Nontransgenic neuronal cultures treated with culture medium (Veh), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, 0.2% final concentration, vol/vol) or Aβ peptides (90 μg ml−1). Cultures were treated with a Smad3 inhibitor (SIS3) 1 h before and throughout the 24 h exposure to Aβ and α1(VI) levels were measured in the medium. (m) Purified neuronal cultures from TβRII wild-type (+) mice or knockout mice (–) lacking TβRII expression in forebrain neurons were treated with vehicle or Aβ peptides (90 μg ml−1), and α1(VI) levels were measured in the medium. For all cell culture studies, n = 4–8 wells per condition from 2–3 independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 versus leftmost bar or as indicated by bracket (Tukey test). Error bars represent s.e.m.

In situ hybridization to identify the cellular source of Col6a1 revealed marked increases in expression in dentate gyrus granule cells in most hAPP-J20 mice (Fig. 1d). Less prominent increases were identified in the pyramidal layer of hippocampal subregions CA1 and CA3 and in the neocortex (Fig. 1d and data not shown).

To determine whether Aβ increases the expression of Col6a1 mRNA and α1(VI) protein in neurons, we incubated primary hippocampal and cortical neurons from nontransgenic mice with synthetic human Aβ42 oligomers (Supplementary Fig. 2 online) or a control peptide with a reversed sequence (Aβrev). Aβ42, but not Aβrev, increased neuronal Col6a1 mRNA and α1(VI) protein levels in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1e,f). Because Aβ5 and collagen I6 bind APP, we tested primary neuronal cultures from APP-deficient mice. Aβ increased α1(VI) expression in these cultures (Fig. 1g), indicating that APP-dependent signaling is not critical in this process.

Because astrocytes participate in clearing extracellular Aβ and contribute to ECM production and remodeling7, we tested their response to Aβ42. Aβ42 did not affect α1(VI) expression in primary astroctye cultures (Fig. 1h), but it did increase α1(VI) expression in mixed neuronal/glial cultures (Fig. 1i). Thus, Aβ42 has neuron-specific effects on α1(VI) expression that are probably independent of astroglial activities.

To determine how Aβ regulates α1(VI) expression, we focused on a Smad3-responsive element in the Col6a1 promoter region, identified in fibroblasts8. The transcription factor Smad3 regulates gene expression that is triggered by the injury-responsive cytokine transforming growth factor (TGF-β)9. Hippocampal TGF-β levels were increased in hAPP-J20 mice (Fig. 1j). In primary neuronal cultures, TGF-β1 increased Col6a1 expression (Fig. 1k). To determine whether TGF-β signaling mediates this effect, we treated primary neurons with a Smad3 inhibitor. Preventing Smad3 activation blocked the Aβ42-induced increase in α1(VI) expression (Fig. 1l). Thus, Smad3 may regulate α1(VI) in neurons as well as in fibroblasts8, and the Aβ42-induced increase in neuronal α1(VI) expression may be mediated by TGF-β and related signaling pathways.

Next, we focused on the TGF-β type II receptor (TβRII), which regulates Smad3 activation9 and can modulate Aβ toxicity10. We tested the effect of Aβ42 on primary neuronal cultures from conditional knockout mice lacking TβRII expression in forebrain neurons. Unlike wild-type neurons, TβRII-deficient neurons failed to increase α1(VI) expression in response to Aβ42 oligomers (Fig. 1m). Taken together, these results suggest that Aβ42-induced increases in neuronal α1(VI) expression involve TβRII-dependent activation of Smad3.

What functions may collagen VI fulfill in the nervous system? Because collagen VI inhibits apoptosis in cells of peripheral organs11, we tested whether it increases neuronal resistance to Aβ neurotoxicity by analyzing primary neuronal cultures from α1(VI)-deficient mice, which cannot produce collagen VI (ref. 12). Although α1(VI) ablation did not diminish the survival of untreated cells, wild-type neurons were more resistant to Aβ42 oligomers than α1(VI)-deficient neurons (Fig. 2a).

Figure 2. Collagen VI blocks neuronal association and neurotoxicity of Aβ42 oligomers.

(a) Primary cultures of purified neocortical/hippocampal neurons from mice with various Col6a1 genotypes treated with Aβ42 or Aβrev (90 μg ml−1) for 24 h. Neurotoxicity was determined by trypan blue staining. (b) Ex situ atomic force microscopy images of fibrillar (pH 7–8) and denatured (pH 2–3) collagen VI. Scale bar represents 200 nm. (c–e) Beginning 1 h before and lasting throughout exposure to Aβ (45 μg ml−1), wild-type neuronal cultures were treated with vehicle, human collagen VI at pH 7–8 (0–100 μg ml−1, c) or pH 2–3 (20 μg ml−1, d), or human collagen I at pH 7–8 (20 μg ml−1, e). n = 4–8 wells/condition in 1–2 independent experiments. (f) Wild-type neuronal cultures were pretreated with vehicle or collagen VI (pH 7–8) and exposed to Aβ42 (45 μg ml−1). After 1 h, the cell association of Aβ42 oligomers was assessed by immunostaining (6E10 antibody). Neuronal nuclei were stained (DAPI, blue). In vehicle-treated cultures, most Aβ was cell associated. In collagen VI–treated cultures, most Aβ was sequestered in large extracellular aggregates. Scale bar represents 10 μm. (g) Mature wild-type neurons (4 weeks) pretreated with vehicle, collagen VI (pH 7–8) or collagen I (pH 7–8) were exposed to Aβ42 (45 μg ml−1) and immunostained for Aβ (red) and microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP-2, green). Scale bar represents 20 μm. (h) Immature neurons were treated with collagen VI and Aβ42 (as in f and g) and double labeled for Aβ (red) and collagen VI (green). Scale bar represents 20 μm. We observed similar immunostaining patterns in three independent experiments per condition. (i) Aggregation of monomeric Aβ42 was monitored by in situ AFM for 3 h. Images show the aggregation state 145 min after incubation of Aβ42 in the absence (top) or presence (bottom) of collagen VI (pH 7–8). Scale bar represents 2 μm. (j,k) Large Aβ aggregates (greater than or equal to40 times 103 nm2, representing >95th percentile in size of all Aβ aggregates, j) and small Aβ aggregates (less than or equal to 4 times 103 nm2, estimated to consist of <40 Aβ peptides, k) visualized by AFM were quantified at 145 min (n = 4 images per condition). AFM results were repeated in two independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 versus leftmost bar or as indicated by bracket (Tukey test or Fisher’s exact test). Error bars represent s.e.m.

We also examined the effect of purified collagen VI on Aβ-induced neurotoxicity more directly. The structure and assembly of collagen are highly dependent on pH13. Fibrillar collagen VI was abundant at pH 7–8, whereas nonfibrillar, denatured species predominated at pH 2–3 (Fig. 2b). Treatment of wild-type and α1(VI)-deficient (data not shown) neurons with collagen VI at pH 7–8 prevented Aβ42-induced cell death in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2c). Denatured collagen VI and fibrillar collagen I were not protective (Fig. 2d,e).

To explore the mechanism of this protection, we examined whether collagen VI alters the interaction of Aβ42 oligomers with neurons in culture. In the absence of collagen VI, Aβ42 oligomers were closely associated with neurons (Fig. 2f), probably reflecting binding of Aβ42 to neuronal surfaces, neuronal uptake of Aβ42 oligomers, or both14, 15. Notably, collagen VI blocked the association of Aβ42 oligomers with immature (Fig. 2f) and mature (Fig. 2g) neurons, whereas collagen I did not (Fig. 2g and data not shown). In the presence of collagen VI, Aβ42 oligomers were sequestered into large aggregates that colocalized with collagen VI in the extracellular milieu (Fig. 2h). Atomic force microscopy showed that collagen VI promoted the assembly of Aβ42 into larger aggregates (Fig. 2i,j), resulting in fewer potentially neurotoxic Aβ oligomers (Fig. 2k). Thus, collagen VI may prevent Aβ42 neurotoxicity, at least in part, by promoting the extracellular sequestration of Aβ42 oligomers and preventing their interaction with neurons.

Our findings reveal previously unknown actions of collagen VI in the nervous system and suggest that increased collagen VI expression in the brains of hAPP mice and individuals with Alzheimer’s disease is a neuroprotective response. It is unlikely that this response is completely specific to Aβ42-induced injury, as hydrogen peroxide also increased Col6a1 expression in primary neurons, albeit to lesser extent than Aβ42 (data not shown). Aβ42 oligomers increased α1(VI) expression in neurons by an astrocyte-independent mechanism involving TβRII and Smad3 activation. TGF-β can promote apoptosis under specific circumstances, but also fulfills many beneficial functions in injury responses and ECM organization. Because hAPP-J20 mice had increased hippocampal levels of TGF-β, this cytokine may mediate the effect of Aβ42 on neuronal collagen VI expression. However, we cannot exclude that another factor or even Aβ itself binds to TβRII, activating TβRII-dependent signaling and gene expression.

The ability of collagen VI to block the interaction between Aβ42 oligomers and neurons is a plausible mechanism for its neuroprotective effect and might be instructive in the development of new therapeutic strategies for treating Alzheimer’s disease. Additional mechanisms cannot be excluded and merit further investigation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank H. Solanoy, X. Wang, G.-Q. Yu and Y. Zhou for excellent technical support, S. Maeda for helpful discussions on AFM, P. Scherer for α1(VI)-deficient mice, R. Jaenisch for CamK-Cre93 transgenic mice, H. Moses for TβRIIfl/fl knockin mice, C. Weissmann for APP-deficient mice, M.-L. Chu for the Col6a1 cDNA, the New York Brain Bank at Columbia University Medical Center for human tissues, G. Howard and S. Ordway for editorial review, J. Carroll, T. Roberts and C. Goodfellow for preparation of graphics, and D. McPherson for administrative assistance. Confocal images were acquired at the Nikon Imaging Center at University of California, San Francisco. This work was supported by grants from the US National Institutes of Health, a medical student fellowship from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, a Larry L. Hillblom Fellowship and a facilities grant from the National Center for Research Resources.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

J.S.C. and D.B.D. conducted the experiments and wrote the manuscript. J.L. performed atomic force microscopy analysis. I.H.C. prepared oligomeric Aβ. I.T., T.W.-C. and P.B. provided animal models and helpful discussions. D.H.K. and G.-Q.Y. provided technical assistance. L.M. supervised the project.

References

- 1.Cheng IH, et al. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:23818–23828. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701078200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Palop JJ, et al. J Neurosci. 2005;25:9686–9693. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2829-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Palop JJ, et al. Neuron. 2007;55:697–711. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mucke L, et al. J Neurosci. 2000;20:4050–4058. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-11-04050.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lorenzo A, et al. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:460–464. doi: 10.1038/74833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beher D, Hesse L, Masters CL, Multhaup G. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:1613–1620. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.3.1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wyss-Coray T, et al. Nat Med. 2003;9:453–457. doi: 10.1038/nm838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Verrecchia F, Chu ML, Mauviel A. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:17058–17062. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100754200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Massagué J, Seoane J, Wotton D. Genes Dev. 2005;19:2783–2810. doi: 10.1101/gad.1350705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tesseur I, et al. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:3060–3069. doi: 10.1172/JCI27341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Irwin WA, et al. Nat Genet. 2003;35:367–371. doi: 10.1038/ng1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bonaldo P, et al. Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7:2135–2140. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.13.2135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chernoff EAG, Chernoff DA. J Vac Sci Technol. 1992;10:596–599. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lacor PN, et al. J Neurosci. 2004;24:10191–10200. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3432-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burdick D, Kosmoski J, Knauer MF, Glabe CG. Brain Res. 1997;746:275–284. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(96)01262-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.