Abstract

Glutamate contributes to the acid tolerance response (ATR) of many Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria, but its role in the ATR of the oral bacterium Streptococcus mutans is unknown. This study describes the discovery and characterization of a glutamate transporter operon designated glnQHMP (Smu.1519 to Smu.1522) and investigates its potential role in acid tolerance. Deletion of glnQHMP resulted in a 95% reduction in transport of radiolabeled glutamate compared to the wild-type UA159 strain. The addition of glutamate to metabolizing UA159 cells resulted in an increased production of acidic end products, whereas the glnQHMP mutant produced less lactic acid than UA159, suggesting a link between glutamate metabolism and acid production and possible acid tolerance. To investigate this possibility, we conducted a microarray analysis with glutamate and under pH 5.5 and pH 7.5 conditions which showed that expression of the glnQHMP operon was downregulated by both glutamate and mild acid. We also measured the growth kinetics of UA159 and its glnQHMP-negative derivative at pH 5.5 and found that the mutant doubled at a much slower rate than the parent strain but survived at pH 3.5 significantly better than the wild type. Taken together, these findings support the involvement of the glutamate transporter operon glnQHMP in the acid tolerance response in S. mutans.

Streptococcus mutans is 1 of over 700 bacterial species commonly found in the oral environment (1). Its ability to rapidly metabolize dietary carbohydrates to acid end products causes demineralization of the tooth enamel, leading to caries formation (19). Acidogenicity (the ability to produce acid end products via glycolysis) and aciduricity (the ability to survive and grow in acidic environments) are two important virulence factors of S. mutans. Maintenance of a pH gradient across the cell membrane by increasing intracellular pH by 0.5 to 1.0 relative to the extracellular pH (ΔpH) when exposed to a low pH environment is critical for the survival of S. mutans at low pH. This is primarily accomplished by acid-induced mechanisms that facilitate proton extrusion via the proton-translocating ATPase (5, 20) and by acid end product efflux (8, 12). S. mutans also possesses an acid tolerance response (ATR) mechanism, whereby preexposure to sublethal pH environments (e.g., pH 5.5) affords protection from killing under lethal pH values as low as pH 3.0 (7). This adaptive process is characterized by increased acid resistance (4), increased glycolytic capacities (20), and increased proton-translocating enzyme F1F0-ATPase activity (44). The ATR is enhanced by sugar starvation and the addition of amino acids (48), the addition of potassium ions (12), growth in biofilms, and activity of multiple two-component signal transduction systems that include the ComDE, HK11/RR11 (also designated LiaS/LiaR), VicKR, CiaHR, LevSR, ScnKR, and HK1037/RR1038 (6, 17, 31, 32, 46).

Previously, Noji et al. and Sato et al. described a glutamate/aspartate transporter in S. mutans (38, 45). Those researchers showed that the presence of potassium ions was required for transport and that, in environments of pH 6.0 or below, the activity of the H+-ATPase system was required (38, 45). Potassium ions are the main cations in plaque (50), and potassium uptake is associated with intracellular pH homeostasis in S. mutans (24, 35). In addition, expression of several genes involved in the glutamate synthesis pathway (icd, citZ, and acn) are downregulated under low pH (10), suggesting a link between glutamate metabolism, potassium levels, and aciduricity in S. mutans. Since acid tolerance is an important virulence property of S. mutans, we aimed to investigate a possible link between glutamate uptake and acid resistance in this oral pathogen. In bacteria, intracellular glutamate and glutamine levels are closely linked with nitrogen metabolism of the cell. Glutamine is synthesized from glutamate and ammonium, which is a major way for cells to assimilate the nitrogen required for biosynthesis of all amino acids, thus affecting protein synthesis and the structural and functional integrity of the cell. Notably, nitrogen metabolism, especially glutamine metabolism, has been linked to virulence in a number of microorganisms, including Streptococcus pneumoniae (26, 42), Staphylococcus aureus (41), Candida albicans (33), and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (51). Glutamate uptake and metabolism are known to be involved in the ATR of Gram-negative bacteria such as Escherichia coli via the use of glutamate decarboxylase and the glutamate/gamma-amino butyrate (glutamate/GABA) antiporter (9). Similarly, the homologous proteins of these systems in Lactococcus lactis, encoded by the gadBC genes, were shown to assist in a glutamate-dependent acid-resistance mechanism in that Gram-positive bacterium (44).

In this study, we searched the S. mutans UA159 genome for potential glutamine transporter operons. We constructed a deletion mutant (SmuGLT) of the glnQHMP operon (Smu.1519 to Smu.1522) and confirmed its role as a glutamate transporter. The inability of SmuGLT to take up glutamate resulted in a general growth deficiency, especially at pH 5.5, as well as an increased tolerance to acid. Results from this study provide insight into the ATR of S. mutans, including a potential link between glutamate metabolism and acid resistance in S. mutans.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

S. mutans wild-type strain UA159 (supplied by J. Ferretti, University of Oklahoma) was used in this study. The S. mutans glnQHMP isogenic knockout mutant (SmuGLT) was generated using PCR ligation mutagenesis as described previously (27). The primers used in this study are shown in Table 1. S. mutans UA159 cells were grown in Todd-Hewitt broth supplemented with 0.3% yeast extract (THYE) as static cultures at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Erythromycin was added to a final concentration of 10 μg/ml as needed.

TABLE 1.

Primers used in the study

| Primer | Sequence (5′ to 3′)a | Description (reference) |

|---|---|---|

| GLT P1 | GCAACAACTCAAACTCACGGTG | glnQHMP mutagenesis |

| GLT P2 | GGCGCGCCACCAAGTAAAACAACAACCTGTCC | glnQHMP mutagenesis |

| GLT P3 | GGCCGGCCAAAGTGGGAACAAGCAACGG | glnQHMP mutagenesis |

| GLT P4 | TCAATGAGCCATCAAGCGAC | glnQHMP mutagenesis |

| ERM For | GGCGCGCCCCGGGCCCAAAATTTGTTTGAT | Erythromycin cassette (27) |

| ERM Rev | GGCCGGCCAGTCGGCAGCGACTCATAGAAT | Erythromycin cassette (27) |

| 16S RT For | CTTACCAGGTCTTGACATCCCG | 16S rRNA qRT-PCR |

| 16S RT Rev | ACCCAACATCTCACGACACGAG | 16S rRNA qRT-PCR |

| 1519 RT For | GACAGGTTGTTGTTTTACTTG | glnQ qRT-PCR |

| 1519 RT Rev | GGTCCTTAGTTGAAGCATTGG | glnQ qRT-PCR |

| 1520 RT For | ATGCTGAGACGGGTAAATACG | glnH qRT-PCR |

| 1520 RT Rev | GAGGTTCACGAGTTTGAGTCG | glnH qRT-PCR |

| 1521 RT For | GAAGTCATTCGCTCTGGTATTGAAG | glnM qRT-PCR |

| 1521 RT Rev | CATTGGTGGCAAGATAGTTCTGATG | glnM qRT-PCR |

| 1522 RT For | AAATGAAATCCACTCCTGCTGG | glnP qRT-PCR |

| 1522 RT Rev | CAAGTCCTGCCTCAGTTTGTCC | glnP qRT-PCR |

| 1530 RT For | GACCGTCAGTGATGGAAATAACG | atpD qRT-PCR |

| 1530 RT Rev | TCTTCATAGCCGTCTTTTGGAAC | atpD qRT-PCR |

| 1531 RT For | CTTACAACTTCAGATTTAGCAG | atpE qRT-PCR |

| 1531 RT Rev | AGAGATTCAGTCCCTATTATC | atpE qRT-PCR |

| 1532 RT For | CGGCTAAAAGAACACTAAG | atpF qRT-PCR |

| 1532 RT Rev | CGGTCGTCTAAAAGATAAG | atpF qRT-PCR |

| 1534 RT For | ACCATACATTTCAGGCTG | atpH qRT-PCR |

| 1534 RT Rev | TTTTAGCACTTGGGATTG | atpH qRT-PCR |

Restriction sites are underlined: AscI, GGCGCGCC; FseI, GGCCGGCC.

Glutamate transport assay.

Glutamate transport assays were performed as described by Noji et al. (38) with minor modifications. S. mutans UA159 colonies were inoculated into 10 ml of modified Berman's broth at pH 7.0 supplemented with 0.1% glucose and incubated overnight. These cultures were subsequently diluted 10-fold into fresh Berman's broth at pH 7.0 and supplemented with 1.0% glucose and incubated to mid-logarithmic phase (optical density at 600 nm [OD600], ∼0.4 to 0.5). The cells were then harvested by centrifugation and washed twice with cold washing buffer (50 mM KPO4, pH 7.2, and 10 mM MgSO4). Cells were then resuspended in the same buffer to an OD600 of ∼4.0. A mixture of 540 μl of cell suspension, 600 μl of reaction buffer (washing buffer and 1% glucose), and chloramphenicol (final concentration, 0.1 mg/ml) was incubated at 37° for 10 min. At time zero, 0.6 μCi l-[U-14C]glutamic acid (260 mCi/mmol) and unlabeled glutamic acid potassium salt monohydrate (final concentration, 0.1 mM) were added, and duplicate aliquots of 100 μl were sampled every 2 min and immediately filtered through a 0.2-μm-pore-size nitrocellulose filter. The filters were washed twice with 1 ml of ice-cold washing buffer and submerged in scintillation fluid, and the internalized radioactivity was determined with a liquid scintillation counter. To obtain dry weights for standardization, duplicate 1-ml aliquots of resuspended cells were filtered through dried, preweighed filters, dried for 24 h, and reweighed.

Cell preparation for gene expression analysis.

For glutamate response assays, overnight cultures of S. mutans UA159 grown in THYE at pH 7.5 (nonbuffered) were split into two aliquots, pelleted by centrifugation, and resuspended in either minimal medium (MM) prepared without glutamic acid (15) or MM supplemented with 10 mM glutamic acid potassium salt monohydrate. These cultures were subsequently diluted 5-fold into MM prepared with or without glutamic acid, incubated from a starting OD600 of ∼0.3 until an OD600 of ∼0.5 was reached, and then harvested by centrifugation and utilized for RNA isolation.

For acid shock assays, overnight cultures of S. mutans UA159 and SmuGLT strains were diluted 10-fold in TYE (10% tryptone, 5% yeast extract, 17.2 mM K2HPO4) supplemented with 0.5% glucose at pH 7.5 and incubated at 37°C until cells reached the mid-logarithmic phase (OD600, ∼0.4). Cell cultures were then divided into two aliquots, pelleted by centrifugation, and resuspended in TYE supplemented with 0.5% glucose at pH 7.5 or pH 5.5. The cells were subsequently incubated for 1 h at 37°C, harvested by centrifugation, and utilized for RNA isolation.

Microarray and quantitative real time PCR (qRT-PCR) gene expression analysis.

Total RNA was isolated and treated with RQ1 RNase-free DNase (Promega) as described previously (21). For microarray analysis, RNA derived from the S. mutans UA159 strain was used as a reference for the control and experimental samples (2). S. mutans UA159, SmuGLT, and reference RNA samples were converted to cDNA and labeled with cyanine 3 (Cy3-labeled control or experimental samples) or cyanine 5 (Cy5-labeled reference samples) as outlined in The J. Craig Venter Institute (JCVI) aminoallyl (aa) labeling protocol M007. The following changes were incorporated into this protocol: the ratio of aa-dUTPs to dTTP was changed to 3:2, and the total amount of RNAs used for cDNA synthesis was increased to 5 μg. The slides were hybridized in a MAUI hybridization chamber (Bio Microsystems Inc.) at 42°C. Scanning of the slides was performed using the GenePix scanner (Axon Instruments Inc., Union City, CA) at 532 nm (Cy3 channel) and 635 nm (Cy5 channel). The scanned images were processed using TIGR's Spotfinder program with default settings. The output data set was then normalized using TIGR's MIDAS program, and analysis was performed using the Biometric Research Branch (BRB) microarray tool. A class prediction analysis was first performed to validate the reproducibility of each biological replicate. The various statistical algorithms used for analysis were as follows: compound covariate predictor, diagonal linear discriminant analysis, 1-nearest neighbor, 3-nearest neighbors, nearest centroid and support vector machines analysis. A class comparison analysis was then used to identify statistically significant genes. The statistical algorithm used was the two-sample t test (with random variance model), with a parametric P value cutoff set to P of <0.001.

For qRT-PCR gene expression analysis, cDNA was generated from RNA isolated as described above, using a first-strand cDNA synthesis kit (MBI Fermentas) according to the manufacturer's instructions. RNA samples lacking reverse transcriptase were included as controls for DNA contamination. The single-stranded cDNA template qRT-PCRs were carried out using the QuantiTect SYBR green PCR kit (Qiagen) in an Mx3000P QPCR system (Stratagene). Specific primer sequences used (Table 1) in the reactions were designed to yield 100- to 150-bp products. For each reaction, the cycle threshold (CT) was measured; this value was inversely proportional to the starting amount of DNA in each sample. All data were normalized against the expression of an internal standard, 16S rRNA. The change in expression was determined using the Pfaffl method (40).

Measurement of glycolytic rates.

Overnight cultures of S. mutans UA159 and SmuGLT strains were diluted 10-fold into THYE at pH 7.5 and incubated at 37°C until cultures reached the mid-logarithmic phase (OD600 of ∼0.4). Cells were harvested by centrifugation and washed twice with cold PK solution (1% peptone, 1% KCl) at pH 7.0. Cells were resuspended in PK solution at the appropriate pH to an OD600 of ∼1.0. Aliquots (18 ml) of cell suspension were equilibrated in the reaction vessel at 37°C until residual glycolytic activity had diminished. Following equilibration, glucose was added to a final concentration of 200 mM, and glycolysis was monitored by the rate of addition of potassium hydroxide (10 mM KOH at pH 7.0 and 2 mM KOH at pH 5.0) required to keep the pH constant, utilizing a Radiometer ABU901 autoburette in conjunction with a PHM290 pH controller (Radiometer, Denmark). After equilibration, 2 M glutamatic acid ammonium salt stock was added to obtain the desired final concentration, and glycolysis was monitored. The glycolytic rate was expressed as nanomoles of acid neutralized per milligram (dry weight) of cells per minute.

Measurement of lactate production.

Overnight cultures of S. mutans UA159 and SmuGLT grown in THYE at pH 7.5 were split into two aliquots, pelleted by centrifugation, and resuspended in either MM prepared without glutamic acid (15) or MM supplemented with 10 mM glutamic acid potassium salt monohydrate. These cultures were subsequently diluted 10-fold using MM supplemented with or without 10 mM glutamic acid and incubated at 37°C. When cultures reached the early logarithmic phase (OD600, ∼0.2 to 0.3), cells were pelleted by centrifugation and the supernatants were diluted 1:4 with distilled water and analyzed using the EnzyChrom lactate assay kit as per the manufacturer's instructions (BioAssay Systems). Results were normalized to OD600 values for each corresponding culture.

Terminal pH assay.

Cultures of S. mutans UA159 and SmuGLT strains were grown in TYE supplemented with 1.0% glucose at pH 7.5 and incubated at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 for 18 h prior to the terminal pH measurement.

Growth kinetics.

Overnight cultures of S. mutans UA159 and SmuGLT strains grown in THYE pH 7.5 were diluted 150-fold by inoculating into 96-well microtiter plates containing THYE buffered with potassium phosphate and sodium citrate, at pH 7.5 or 5.5. Growth kinetics were monitored at 37°C for 24 h using an automated growth monitor (Bioscreen C; Labsystems, Finland). From these data, growth curves were generated and doubling times were calculated as previously described (25).

ATR assay.

Overnight cultures of S. mutans UA159 and SmuGLT strains grown in THYE were diluted 10-fold into TYE supplemented with 0.5% glucose at pH 7.5 and incubated at 37°C until an OD600 of ∼0.4 was reached. Cultures were then divided into two equal aliquots and pelleted via centrifugation. For nonadapted cells, one aliquot was resuspended in TYE at a lethal pH value of 3.5, whereas adapted cells were derived by first resuspending the second aliquot in TYE at pH 5.5 and incubating it at 37°C for 2 h before exposing cells to TYE at pH 3.5. For both adapted and nonadapted cells immersed in TYE at pH 3.5, aliquots were removed every hour starting at time zero, up to 3 h. At each time point, cells in each aliquot were sonicated for 10 s, serially diluted in 10 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.2), and 20 μl of each dilution was spotted in triplicate onto THYE agar plates and incubated at 37°C for 2 days. The ATR was expressed as the percentage of cells that survived the lethal pH for 3 h compared to the number of cells present at time zero.

RESULTS

Identification of a novel putative glutamate transporter locus.

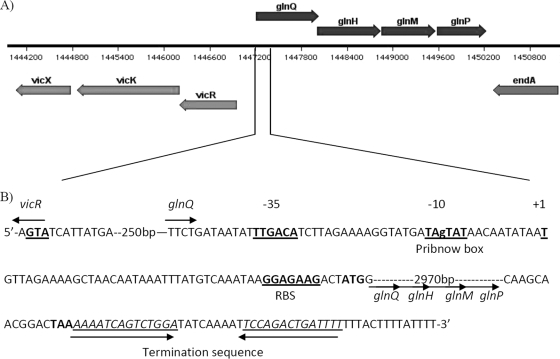

It is already known that glutamate can play a role in the ATR of both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria, but this has not yet been shown for the acid-tolerant oral bacterium S. mutans. A BLAST search of the S. mutans UA159 genome using known glutamine transporter genes as a query revealed a putative operon, designated glnQHMP, encoded by four genes (Smu.1519 to Smu.1522) spanning bp 1,447,261 to 1,450,239 of the UA159 genome (Fig. 1A). This operon, as shown by reverse transcription of glnQHMP mRNA and amplification of the three intergenic regions from S. mutans cDNA (data not shown), is a tetracistronic transcript consisting of four gene products, namely, Smu.1519 to Smu.1522. A Blastp analysis of each gene product showed that these genes encode a putative ABC transporter similar to those found in closely related streptococci (percentage identity ranging from 77% to 85% for Smu.1519, Smu.1521, and Smu.1522 and 68% for Smu.1520). The four genes were therefore designated as follows: glnQ (ATP-binding protein), glnH (solute-binding protein), glnM (permease), and glnP (membrane-spanning protein). The promoter region of the glnQHMP operon is located approximately 100 bp upstream of the ATG start site of glnQ (Fig. 1B). A putative transcriptional start site (position 1) was located 45 bp upstream of the putative start codon of glnQ. A highly conserved putative Pribnow box (−10 box; TAgTAT) was found 10 bases upstream of the transcriptional start site, and a putative −35 box (TTGACA) was separated by 17 bp from the Pribnow box. A putative ribosome-binding site (GGAGAAG) was identified 3 bp upstream of the start codon, and a putative termination sequence was identified following the TAA stop codon of glnM and spanned 37 bp.

FIG. 1.

Map of the glutamate transporter operon Smu.1519 to Smu.1522. The transporter operon is located upstream of the TCSTS operon VicRKX (A). Analysis of the glnQ promoter region identified the putative −10 box, −35 box, transcriptional start site, and ribosome binding site (RBS) (all underlined in bold) as well as the putative termination sequence (underlined) (B).

glnQHMP mutagenesis affects glutamate transport.

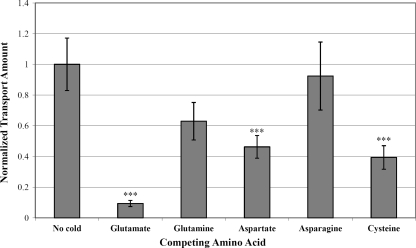

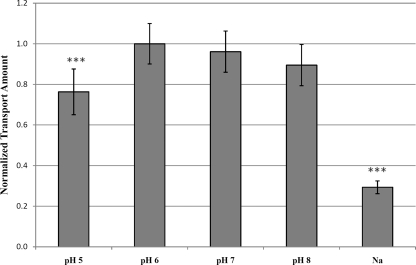

To characterize the glnQHMP operon and examine its role as a glutamate transporter in S. mutans, an isogenic knockout mutant of the entire glnQHMP operon was constructed in the UA159 background. This mutant, designated SmuGLT, was assayed for glutamate uptake by using 14C-radiolabeled glutamic acid (Fig. 2). Compared with its wild-type UA159 parent strain, glnQHMP mutagenesis drastically impaired the ability of the SmuGLT strain to transport glutamate into the cell (Fig. 2). More specifically, relative to the parent, which demonstrated a maximum transport rate of 27.73 pmol/mg (dry weight)/min, glutamate transport by the SmuGLT mutant was significantly reduced, as evidenced by a maximum transport rate of 1.49 pmol/mg (dry weight)/min (P < 0.001). To determine possible competing substrates, maximal uptake of l-[U-14C]glutamic acid by S. mutans UA159 was measured in the presence of a 10× excess of unlabeled competing amino acids (e.g., glutamate, glutamine, asparagine, aspartate, and cysteine). Optimal uptake of labeled glutamate was then normalized to its maximal uptake in the absence of competing amino acids. Results from these competition assays revealed that labeled glutamate uptake was almost completely inhibited by an excess of glutamate (Fig. 3), thus demonstrating high specificity by the GlnQHMP transporter for this amino acid. Moreover, the addition of excesses of aspartate and cysteine partially but significantly inhibited glutamate transport, thereby suggesting a possible role for GlnQHMP in aspartate transport, as previously described by Noji et al. (32), as well as cysteine transport (P < 0.05). Transport was optimal in the presence of potassium ions compared to sodium ions and was slightly, but not significantly, higher at pH 6.0 than at pH 7.0 or 8.0 and significantly higher (P < 0.05) than at pH 5.0; these results are in agreement with previous work by Noji et al. (38) and Sato et al. (45) (Fig. 4).

FIG. 2.

Uptake of L-[U-14C]glutamic acid by S. mutans UA159 (▪) and SmuGLT (□). The maximal rate of glutamate uptake (measured after 2 min of incubation with labeled glutamate) for UA159 was over 18 times higher than that of SmuGLT (P < 0.001; n = 3).

FIG. 3.

Uptake of L-[U-14C]glutamic acid by S. mutans UA159 in the presence of a 10× excess of competing amino acids. Maximal uptake was measured after 2 min of incubation with labeled glutamic acid and unlabeled competing amino acids and then normalized to the maximal uptake in the absence of competing amino acids. Uptake was almost completely inhibited by an excess of glutamate, partially inhibited by an excess of aspartate and cysteine, and somewhat inhibited by an excess of glutamine. ***, P < 0.05 (n = 7).

FIG. 4.

Uptake of L-[U-14C]glutamic acid by S. mutans UA159 in buffer of various pHs and with different metal ions. Maximal uptake was measured after 2 min of incubation with labeled glutamic acid in the presence of potassium ions and then normalized to the maximal uptake in buffer at pH 6.0. Uptake was significantly decreased under acidic assay conditions and in the presence of sodium ions. ***, P < 0.05 (n = 6).

glnQHMP mutagenesis results in decreased acid production.

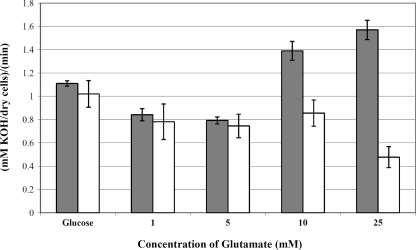

Glutamate is metabolized within the cell through the urea and citrate cycles to phospho-enol-pyruvate, which enters the glycolytic pathway and can be metabolized to form organic acid end products (11). Therefore, we expected a possible connection between glutamate transport and proton extrusion. During growth under conditions of excess carbohydrate, the main glycolytic end product is lactic acid, which can be quantified as a measure of glycolysis. To establish a link between glutamate uptake and acid production, we assayed the glycolytic rates of S. mutans UA159 in the presence and absence of glutamate. Our results revealed that the addition of exogenous glutamate resulted in a 40% increase in the glycolytic rate of the UA159 strain, from 1.1 mmol/min/mg in the absence of glutamate to 1.55 mmol/min/mg by adding 25 mM glutamate (Fig. 5). At glutamate levels below 10 mM, glycolysis was not significantly different from the 0 mM glutamate control (i.e., glucose-only) samples. The amount of glucose used in the experiments was extremely high (200 mM, equivalent to 20%, wt/vol), and therefore a large amount of acid was generated. The amount of acid generated by the lower glutamate concentrations would not be enough to show an increase compared to the glucose-only data.

FIG. 5.

Glycolytic rates of S. mutans UA159 (gray bars) and SmuGLT (white bars). Glycolytic rates were monitored by measuring the rate of addition of 10 mM KOH to the cell suspension following the addition of 200 mM glucose and subsequently increasing the amounts of glutamate at pH 7.0 (n = 3).

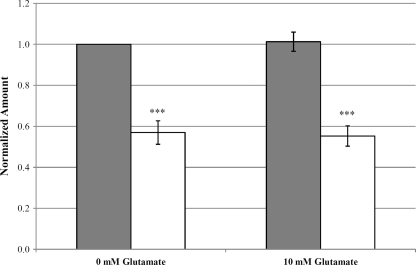

Since glutamate increased the production of acid in cultures of wild-type S. mutans, our next step was to determine the contribution of the GlnQHMP transporter to this process. We first measured the terminal culture pHs of S. mutans UA159 and SmuGLT cultures after 18 h of growth in TYE. From an initial pH of 7.5, SmuGLT was unable to acidify the cultures to the same extent as S. mutans UA159 (final pHs of 4.33 ± 0.047 versus 4.18 ± 0.053, respectively; P < 0.001). Because this was likely a result of the increased production of lactic acid by the parent strain due to glutamate metabolism, we examined lactate production by S. mutans UA159 and SmuGLT. Lactate production assays revealed that SmuGLT cultures produced 40% less lactate than S. mutans UA159 cultures (P < 0.001) (Fig. 6). Interestingly, the addition of glutamate did not increase lactate production by S. mutans UA159 above the background level of lactate produced via fermentation of the glucose present in the medium (MM supplemented with 1% glucose).

FIG. 6.

Lactate production of S. mutans UA159 (gray bars) and SmuGLT (white bars) cultures grown in MM in the presence of 10 mM glutamate. Amounts were normalized to corresponding OD600 values for each culture. SmuGLT produced significantly less lactate during than UA159. ***, P < 0.001 (n = 5).

Glutamate transporter contributes to the acid tolerance response.

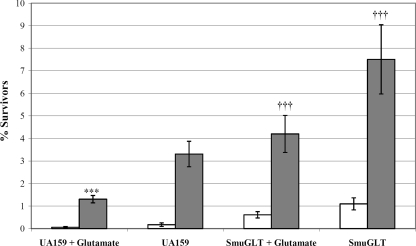

Since deficiency of the glutamate transporter had a drastic effect on the acidogenicity of S. mutans, we investigated the importance of glutamate transport on the ability of S. mutans UA159 to survive in an acidic environment. The effect of the glnQHMP deletion on acid tolerance in S. mutans UA159 was initially assayed by measuring growth rates at pH 5.5 (Table 2). Growth kinetics showed that SmuGLT grew significantly more slowly at pH 5.5 than S. mutans UA159 (mean doubling times of 265.9 ± 13.4 min versus 208.9 ± 8.4 min, respectively). Since SmuGLT growth was also compromised at pH 7.5, with mean doubling times of 63.5 ± 1.9 min versus 56.0 ± 1.3 min for S. mutans UA159, we performed a killing assay using S. mutans UA159 and SmuGLT strains to determine whether the absence of the glutamate transporter affected survival under acidic conditions. ATR assays were conducted in the presence and absence of 10 mM glutamate by exposing cells to pH 3.5 with or without prior exposure to a sublethal inducing pH of 5.5. Preincubation at this adaptive pH of 5.5 increased survival at the lethal pH of 3.5 for both S. mutans UA159 and SmuGLT in all instances (Fig. 7). While the presence of glutamate decreased the ability of adapted S. mutans UA159 cells to survive the pH 3.5 challenge, ATR assays revealed that SmuGLT cells were able to better survive the acid challenge than S. mutans UA159 cells, even when unadapted, in the presence and absence of glutamate (Fig. 7).

TABLE 2.

Doubling times of S. mutans strains growing exponentially in THYE

| Growth condition | Doubling time (min) for: |

|

|---|---|---|

| UA159 | SmuGLT | |

| THYE (unbuffered) | 73.3 ± 3.4 | 76.9 ± 1.4 |

| THYE, pH 7.5 | 56 ± 1.3 | 63.5 ± 1.9a |

| THYE, pH 5.5 | 208.9 ± 8.4 | 265.9 ± 13.4a |

| 0.4 M NaCl | 150.1 ± 10.1 | 183.0 ± 10.6a |

| 5% ethanol | 227.0 ± 30.0 | 417.1 ± 44.5a |

| 0.0025% SDS | 90.0 ± 2.7 | 93.0 ± 1.9 |

Statistically significant differences were observed between the doubling times of parent versus mutant strains (Student's t test, P < 0.05).

FIG. 7.

Acid tolerance responses of S. mutans UA159 and SmuGLT. Cells were grown in TYE (pH 7.5) supplemented with glucose and were exposed to TYE pH 3.5 (unadapted UA159 and SmuGLT [white bars]) or incubated in TYE pH 5.5 for 2 h and then exposed to TYE pH 3.5 (adapted UA159 and SmuGLT [gray bars]). Results are shown as the percentage of the original cell count surviving after incubation at the lethal pH of 3.5 for 3 h. Glutamate significantly decreased the ATR for UA159. ***, P < 0.01 (n = 5). SmuGLT had a significantly increased ATR compared to UA159. †††, P < 0.05 (n = 5).

Loss of the glutamate transporter results in growth deficiency under salt and ethanol stress conditions.

Since SmuGLT was altered in its response to acidic conditions, we tested the mutant's ability to grow under stresses induced by 0.4 M NaCl, 0.5% ethanol, and 0.0025% SDS. As shown in Table 2, growth kinetics showed that SmuGLT grew significantly slower than S. mutans UA159 in the presence of 0.4 M NaCl as well as with 5% ethanol (P < 0.05), thereby suggesting a possible role for glutamate uptake in tolerating these environmental stressors. In contrast, growth of the mutant was unaffected by the presence of 0.0025% SDS.

Low pH downregulates glnQHMP expression.

Since our results indicated a potential link between glutamate transport and acid tolerance, we investigated glutamate transporter expression under low pH. Briefly, qRT-PCR was utilized using cDNAs derived from S. mutans UA159 cells grown in pH 7.5 versus pH 5.5. Quantitative real-time PCR indicated that glutamate transporter expression was downregulated under low pH by 2.5- to 3.7-fold relative to neutral conditions (Table 3). Not surprisingly, in accordance with previous reports, expression of F1F0-ATPases that function as proton pumps and eject H+ from the cell and play an important role in maintaining S. mutans intracellular pH homeostasis (44) was upregulated approximately 2-fold under acidic conditions.

TABLE 3.

Gene expression data for S. mutans UA159

| Gene locus | Gene name | Result with glutamatea |

Result at pH 5.5b |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microarray | qRT-PCR | Microarray | qRT-PCR | ||

| Smu.1519 | glnQ | −5.29 | −3.9 | −2.48 | −2.91 |

| Smu.1520 | glnH | −3.45 | −3.8 | −2.58 | −3.71 |

| Smu.1521 | glnM | −3.26 | −4.5 | −2.70 | −3.12 |

| Smu.1522 | glnP | No change | −3.4 | No change | −2.54 |

| Smu.1528 | F1F0-ATPase | +4.27 | NDc | +2.44 | ND |

| Smu.1530 | F1F0-ATPase | +6.04 | −1.3 | +1.88 | ND |

| Smu.1531 | F1F0-ATPase | +9.48 | +4.7 | +1.82 | ND |

| Smu.1532 | F1F0-ATPase | +3.20 | +1.1 | +2.32 | ND |

| Smu.1533 | F1F0-ATPase | +3.96 | ND | +2.45 | ND |

| Smu.1534 | F1F0-ATPase | +6.49 | +1.1 | +1.70 | ND |

Expression in cultures grown in minimal medium and exposed to 10 mM glutamic acid potassium salt monohydrate, compared to paired cultures grown in minimal medium without glutamate (P < 0.05; n = 4).

Expression in cultures grown at pH 5.5 compared to paired cultures grown at pH 7.5 (P < 0.05; n = 4).

ND, not determined.

S. mutans global expression profile in the presence of glutamate.

To identify potential regulators of glutamate transport, DNA microarrays were performed using mid-logarithmic-phase S. mutans UA159 cells grown in minimal medium in the presence and absence of glutamate. Microarray results indicated that 117 transcripts representing genes were affected over 2-fold in the presence of glutamate, with 79 being upregulated and 38 being downregulated (see Tables S1 and S2 in the supplemental material). Not surprisingly, relative to expression in glutamate-supplemented medium, the glnQHMP operon was upregulated between 3.3- and 5.3-fold in the absence of added glutamate, a result confirmed using qRT-PCR analysis, suggesting a putative glutamate scavenging role for this transporter in S. mutans and potentially autoregulation of expression by glutamate (Table 3). Thirteen other transport and binding protein transcripts were affected in the presence of glutamate, 14 energy metabolism transcripts were affected, most notably Smu.1528 (+4.3-fold) and Smu.1530 to Smu.1534 (+3.2 to +9.5-fold) (Table 3), which are the proton-translocating F1F0-ATPases, and 10 amino acid biosynthesis transcripts were affected.

Several transcripts of proteins with transcriptional regulatory functions were also affected by the addition of glutamate, including Smu.1924 (+2.3-fold), the response regulator GcrR, Smu.61 (−2.4-fold), a putative DNA-binding protein belonging to the xenobiotic response element family of transcriptional regulators, and Smu.124 (−2.4-fold), a homolog of the transcription regulator/repressor multiple antibiotic resistance regulator (MarR) family. These results were confirmed by qRT-PCR (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

S. mutans employs well-known strategies to survive the acid environment of the oral cavity subsequent to carbohydrate metabolism. As pH levels in plaque can drop to below pH 3.0 within minutes of carbohydrate consumption, acid tolerance is an important virulence factor for S. mutans. Any factor that could convey a survival advantage under acidic conditions would be of benefit to the cells. Glutamate is known to play a role in the ATR of Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria (9, 44), but it has not been previously linked to the ATR of S. mutans. In this study, we investigated the involvement of the S. mutans glutamate transporter operon glnQHMP and its role in aciduricity.

Radiolabeled uptake assays with wild-type cells and the isogenic mutant of the glnQHMP operon indicated that glnQHMP facilitates transport of glutamate, thereby confirming its role as a novel glutamate transporter in S. mutans. Interestingly, loss of the GlnQHMP transporter did not significantly reduce glutamine uptake relative to the wild type, although in competition assays, unlabeled glutamine was able to markedly, but not significantly, decrease uptake of unlabeled glutamine (Fig. 3), suggesting that GlnQHMP is mainly dedicated to the transport of glutamate into S. mutans.

Altered expression patterns and activities of amino acid transporters have previously been shown under low pH conditions in Streptococcus pneumoniae, in which exposure to acid downregulated expression of the glutamine transporter genes spr1120 and spr1121 (36). Similarly, in S. mutans, acid-induced stress results in decreased activity of amino acid transporters in planktonic cells (37), and the addition of amino acids was shown to induce the synthesis of known ATR proteins (49). It has also been noted in S. mutans that potassium ions accelerate acid excretion especially at low pH, whereas sodium ions decrease proton extrusion (24). According to Sato et al. (45) and results from our lab, transport of glutamate is markedly increased in the presence of potassium ions compared to the presence of sodium ions (Fig. 4). Sato et al. also noted that the stimulatory effect of potassium on glutamate transport at pH 6.0 and lower was partially, but not completely, due to regulation of intracellular pH (45). However, we found that the addition of glutamate resulted in a decreased ATR, at least under planktonic conditions, by S. mutans UA159. One explanation for the decreased ATR is that the addition of glutamate to metabolically active cells resulted in higher levels of acid production, a theory supported by the increased expression of the proton-translocating F1F0-ATPases under these conditions. Perhaps it is likely that the cells had difficulty coping with this increased “acid load” in the presence of excess glutamate, thereby resulting in decreased survival under highly acidic conditions. This theory is supported by the fact that the mutant SmuGLT, which is unable to transport glutamate, produces less lactate and is capable of surviving an acid challenge significantly better than the parent strain.

Another explanation for the increased ATR of SmuGLT is likely attributable to its slower growth rate relative to S. mutans UA159 under nonstressed conditions at pH 7.5, as well as under stresses induced in the presence of sodium chloride, ethanol, and low pH. Cells growing within biofilms, which harbor slow-growing cells, demonstrate an increased resistance to killing by antimicrobials and various environmental stressors relative to their planktonic counterparts (29, 30, 34). Moreover, in Lactococcus lactis, H+-ATPase is one of the ATR proteins induced by acid pHi through growth at an acid pHo or a slow growth rate (39). However, counteracting this argument, Belli and Marquis have shown that slower-growing continuous cultures of S. mutans GS-5 have a somewhat decreased ability to mount an ATR (4).

In both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria, potassium glutamate has been linked to osmoregulation (18, 28). In E. coli, accumulation of potassium glutamate immediately after osmotic shock provides temporary protection to the cells and either inhibits gene transcription by directly inhibiting RNA polymerase binding or increases transcription by acting through sigma-38 or by direct interaction on select gene promoters (18). In Oenococcus oeni, glutamate-containing peptides confer protection from salt-induced osmotic stress (28), and in Bacillus subtilis it is speculated that osmotic stress may result in an enhanced requirement for glutamate to generate an increased level of the known osmoprotectant proline (23). The increased sensitivity of SmuGLT to salt-induced stress suggests that glutamate may also play a role as an osmoprotectant in S. mutans. Further studies are warranted to define the role of potassium glutamate in the general stress response of S. mutans.

The addition of glutamate to S. mutans UA159 resulted in the altered expression of over 100 gene transcripts, including several potential regulatory proteins. Based on its location immediately upstream of the glnQHMP operon, one of its putative regulatory candidates includes the VicKR two-component system, which is comprised of a membrane-bound sensor kinase and its cognate response regulator, respectively (Fig. 1A) (47). Despite our repeated attempts, we were not able to conclusively show that VicKR had a regulatory role in glnQHMP transcription with or without added glutamate, based on qRT-PCR, under similar experimental conditions used for our glutamate microarray study (unpublished data). However, it is important to note that microarray results using cells derived from the VicK mutant versus UA159 cultures supplemented with or without 10 mM potassium glutamate showed a drastically distinct transcriptional profile between the two strains (unpublished data). Although this observation suggests that VicK is likely responsive to potassium glutamate, more studies are needed to understand the putative regulatory role of VicKR on regulation of GlnQHMP in S. mutans.

Among other potential regulators of interest are Smu.1924, which was upregulated 2.3-fold in response to the addition of glutamate. Smu.1924 (data not shown) encodes an orphan response regulator, GcrR, which has been shown to control the ATR in S. mutans UA159 (13). Since several known ATR genes have shown to be positively regulated by GcrR, which include the F1F0-ATPase atpA/E and the bacterial signal recognition particle ffh (13), it is possible that expression of gcrR is upregulated in response to increased acid production resulting from glutamate metabolism. Another gene of interest that may have a regulatory effect on glnQHMP transcription is the marR homolog, Smu.124, which was downregulated 2.4-fold in response to the addition of glutamate (data not shown). Smu.124, which may function as a transcription regulator/repressor, belongs to the MarR family. Members of this family have been shown to be involved in regulation of virulence factors, catabolism of aromatic compounds, and response to antibiotics and oxidative stress and act to prevent gene expression by sterically hindering transcription (3, 14, 22). Smu.124 is located upstream of four genes (Smu.127 to Smu.130) involved in the metabolism of pyruvate, which is a product of glycolysis and amino acid metabolism. These four genes act to metabolize pyruvate to acetyl coenzyme A, which can be further metabolized to acetate, formate, and ethanol end products. An increased expression of these genes would favor the production of acetate, formate, and ethanol over the production of lactate, which would help S. mutans maintain pH homeostasis. Glutamate may act as the ligand for Smu.124, resulting in transcriptional derepression of Smu.127 to Smu.130, which are required for glutamate metabolism. Additionally, Smu.61, a putative DNA binding protein belonging to the xenobiotic response element family of transcriptional regulators, was downregulated 2.4-fold in response to glutamate (data not shown). The XRE family of transcriptional regulators include the Cro/cI genes, which act as a binary switch to control gene expression in the lambda phage (43), and the virulence regulator PlcR of Bacillus cereus, which controls most known virulence factors in this Gram-positive pathogen (16). However, little is currently known about this family of regulators in S. mutans.

Taken collectively, our findings in the present study reveal a novel ABC transporter in S. mutans that is upregulated under conditions of nutrient deprivation to transport glutamate. We have demonstrated a dynamic relationship between the uptake of glutamate and its effects on two important virulence attributes of S. mutans, acid production and acid tolerance, which are important factors that affect its survival and persistence in the plaque biofilm. Since glutamate transporters are widespread among prokaryotes and because glutamate is an important building block of the bacterial cell wall, understanding how these transporters are regulated at the genetic level may provide substantial insight into amino acid metabolic pathways of bacteria. Such investigations should provide more insight into how nutrient acquisition can be regulated to potentially control bacterial virulence.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIH grant R01DE013230 and CIHR grant MT-15431 to D.G.C. D.G.C. is a Canada Research Chair.

We thank Sheela Manek and Jennifer Lamonaca-Bada for technical assistance and Julie Perry for her critical reading of the manuscript and many helpful suggestions.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 18 December 2009.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aas, J. A., B. J. Paster, L. N. Stokes, I. Olsen, and F. E. Dewhirst. 2005. Defining the normal bacterial flora of the oral cavity. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:5721-5732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abranches, J., M. M. Candella, Z. T. Wen, H. V. Baker, and R. A. Burne. 2006. Different roles of EIIABMan and EIIGlc in regulation of energy metabolism, biofilm development, and competence in Streptococcus mutans. J. Bacteriol. 188:3748-3756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alekshun, M. N., S. B. Levy, T. R. Mealy, B. A. Seaton, and J. F. Head. 2001. The crystal structure of MarR, a regulator of multiple antibiotic resistance, at 2.3 Å resolution. Nat. Struct. Biol. 8:710-714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belli, W. A., and R. E. Marquis. 1991. Adaptation of Streptococcus mutans and Enterococcus hirae to acid stress in continuous culture. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 57:1134-1138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bender, G. R., S. V. Sutton, and R. E. Marquis. 1986. Acid tolerance, proton permeabilities, and membrane ATPases of oral streptococci. Infect. Immun. 53:331-338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Biswas, I., L. Drake, D. Erkina, and S. Biswas. 2008. Involvement of sensor kinases in the stress tolerance response of Streptococcus mutans. J. Bacteriol. 190:68-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bowden, G. H., and I. R. Hamilton. 1989. Competition between Streptococcus mutans and Lactobacillus casei in mixed continuous culture. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 4:57-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carlsson, J., and I. R. Hamilton. 1996. Differential toxic effects of lactate and acetate on the metabolism of Streptococcus mutans and Streptococcus sanguis. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 11:412-419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Castanie-Cornet, M. P., T. A. Penfound, D. Smith, J. F. Elliott, and J. W. Foster. 1999. Control of acid resistance in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 181:3525-3535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chia, J. S., Y. Y. Lee, P. T. Huang, and J. Y. Chen. 2001. Identification of stress-responsive genes in Streptococcus mutans by differential display reverse transcription-PCR. Infect. Immun. 69:2493-2501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cvitkovitch, D. G., J. A. Gutierrez, and A. S. Bleiweis. 1997. Role of the citrate pathway in glutamate biosynthesis by Streptococcus mutans. J. Bacteriol. 179:650-655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dashper, S. G., and E. C. Reynolds. 1996. Lactic acid excretion by Streptococcus mutans. Microbiol. Rev. 142:33-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dunning, D. W., L. W. McCall, W. F. Powell, Jr., W. T. Arscott, E. M. McConocha, C. J. McClurg, S. D. Goodman, and G. A. Spatafora. 2008. SloR modulation of the Streptococcus mutans acid tolerance response involves the GcrR response regulator as an essential intermediary. Microbiology 154:1132-1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fiorentino, G., R. Ronca, R. Cannio, M. Rossi, and S. Bartolucci. 2007. MarR-like transcriptional regulator involved in detoxification of aromatic compounds in Sulfolobus solfataricus. J. Bacteriol. 189:7351-7360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fujiwara, S., S. Kobayashi, and H. Nakayama. 1978. Development of a minimal medium for Streptococcus mutans. Arch. Oral Biol. 23:601-602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gohar, M., K. Faegri, S. Perchat, S. Ravnum, O. A. Okstad, M. Gominet, A. B. Kolsto, and D. Lereclus. 2008. The PlcR virulence regulon of Bacillus cereus. PLoS One 3:e2793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gong, Y., X. L. Tian, T. Sutherland, G. Sisson, J. Mai, J. Ling, and Y. H. Li. 2009. Global transcriptional analysis of acid-inducible genes in Streptococcus mutans: multiple two-component systems involved in acid adaptation. Microbiology 155:3322-3332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gralla, J. D., and D. R. Vargas. 2006. Potassium glutamate as a transcriptional inhibitor during bacterial osmoregulation. EMBO J. 25:1515-1521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hamada, S., and H. D. Slade. 1980. Biology, immunology, and cariogenicity of Streptococcus mutans. Microbiol. Rev. 44:331-384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hamilton, I. R., and N. D. Buckley. 1991. Adaptation by Streptococcus mutans to acid tolerance. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 6:65-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hanna, M. N., R. J. Ferguson, Y. H. Li, and D. G. Cvitkovitch. 2001. uvrA is an acid-inducible gene involved in the adaptive response to low pH in Streptococcus mutans. J. Bacteriol. 183:5964-5973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haque, M. M., M. S. Kabir, L. Q. Aini, H. Hirata, and S. Tsuyumu. 2009. SlyA, a MarR family transcriptional regulator, is essential for virulence in Dickeya dadantii 3937. J. Bacteriol. 191:5409-5418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoper, D., J. Bernhardt, and M. Hecker. 2006. Salt stress adaptation of Bacillus subtilis: a physiological proteomics approach. Proteomics 6:1550-1562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iwami, Y., N. Guha-Chowdhury, and T. Yamada. 1997. Effect of sodium and potassium ions on intracellular pH and proton excretion in glycolyzing cells of Streptococcus mutans NCTC 10449 under strictly anaerobic conditions. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 12:77-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khalichi, P., D. G. Cvitkovitch, and J. P. Santerre. 2004. Effect of composite resin biodegradation products on oral streptococcal growth. Biomaterials 25:5467-5472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kloosterman, T. G., W. T. Hendriksen, J. J. Bijlsma, H. J. Bootsma, S. A. van Hijum, J. Kok, P. W. Hermans, and O. P. Kuipers. 2006. Regulation of glutamine and glutamate metabolism by GlnR and GlnA in Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Biol. Chem. 281:25097-25109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lau, P. C., C. K. Sung, J. H. Lee, D. A. Morrison, and D. G. Cvitkovitch. 2002. PCR ligation mutagenesis in transformable streptococci: application and efficiency. J. Microbiol. Methods 49:193-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Le Marrec, C., E. Bon, and A. Lonvaud-Funel. 2007. Tolerance to high osmolality of the lactic acid bacterium Oenococcus oeni and identification of potential osmoprotectants. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 115:335-342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lewis, K. 2005. Persister cells and the riddle of biofilm survival. Biochemistry (Moscow) 70:267-274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lewis, K. 2001. Riddle of biofilm resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:999-1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li, Y. H., M. N. Hanna, G. Svensater, R. P. Ellen, and D. G. Cvitkovitch. 2001. Cell density modulates acid adaptation in Streptococcus mutans: implications for survival in biofilms. J. Bacteriol. 183:6875-6884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li, Y. H., P. C. Lau, N. Tang, G. Svensater, R. P. Ellen, and D. G. Cvitkovitch. 2002. Novel two-component regulatory system involved in biofilm formation and acid resistance in Streptococcus mutans. J. Bacteriol. 184:6333-6342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liao, W. L., A. M. Ramon, and W. A. Fonzi. 2008. GLN3 encodes a global regulator of nitrogen metabolism and virulence of Candida albicans. Fungal Genet. Biol. 45:514-526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marsh, P. D. 2004. Dental plaque as a microbial biofilm. Caries Res. 38:204-211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marsh, P. D., M. I. Williamson, C. W. Keevil, A. S. McDermid, and D. C. Ellwood. 1982. Influence of sodium and potassium ions on acid production by washed cells of Streptococcus mutans ingbritt and Streptococcus sanguis NCTC 7865 grown in a chemostat. Infect. Immun. 36:476-483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martin-Galiano, A. J., K. Overweg, M. J. Ferrandiz, M. Reuter, J. M. Wells, and A. G. de la Campa. 2005. Transcriptional analysis of the acid tolerance response in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Microbiology 151:3935-3946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McNeill, K., and I. R. Hamilton. 2004. Effect of acid stress on the physiology of biofilm cells of Streptococcus mutans. Microbiology 150:735-742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Noji, S., Y. Sato, R. Suzuki, and S. Taniguchi. 1988. Effect of intracellular pH and potassium ions on a primary transport system for glutamate/aspartate in Streptococcus mutans. Eur. J. Biochem. 175:491-495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.O'Sullivan, E., and S. Condon. 1999. Relationship between acid tolerance, cytoplasmic pH, and ATP and H+-ATPase levels in chemostat cultures of Lactococcus lactis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:2287-2293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pfaffl, M. W. 2001. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 29:e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pohl, K., P. Francois, L. Stenz, F. Schlink, T. Geiger, S. Herbert, C. Goerke, J. Schrenzel, and C. Wolz. 2009. CodY in Staphylococcus aureus: a regulatory link between metabolism and virulence gene expression. J. Bacteriol. 191:2953-2963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Polissi, A., A. Pontiggia, G. Feger, M. Altieri, H. Mottl, L. Ferrari, and D. Simon. 1998. Large-scale identification of virulence genes from Streptococcus pneumoniae. Infect. Immun. 66:5620-5629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reichardt, L. F. 1975. Control of bacteriophage lambda repressor synthesis after phage infection: the role of the N, cII, cIII and cro products. J. Mol. Biol. 93:267-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sanders, J. W., K. Leenhouts, J. Burghoorn, J. R. Brands, G. Venema, and J. Kok. 1998. A chloride-inducible acid resistance mechanism in Lactococcus lactis and its regulation. Mol. Microbiol. 27:299-310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sato, Y., S. Noji, R. Suzuki, and S. Taniguchi. 1989. Dual mechanism for stimulation of glutamate transport by potassium ions in Streptococcus mutans. J. Bacteriol. 171:4963-4966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Senadheera, D., K. Krastel, R. Mair, A. Persadmehr, J. Abranches, R. A. Burne, and D. G. Cvitkovitch. 2009. Inactivation of VicK affects acid production and acid survival of Streptococcus mutans. J. Bacteriol. 191:6415-6424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Senadheera, M. D., B. Guggenheim, G. A. Spatafora, Y. C. Huang, J. Choi, D. C. Hung, J. S. Treglown, S. D. Goodman, R. P. Ellen, and D. G. Cvitkovitch. 2005. A VicRK signal transduction system in Streptococcus mutans affects gtfBCD, gbpB, and ftf expression, biofilm formation, and genetic competence development. J. Bacteriol. 187:4064-4076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Svensater, G., O. Bjornsson, and I. R. Hamilton. 2001. Effect of carbon starvation and proteolytic activity on stationary-phase acid tolerance of Streptococcus mutans. Microbiology 147:2971-2979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Svensater, G., J. Welin, J. C. Wilkins, D. Beighton, and I. R. Hamilton. 2001. Protein expression by planktonic and biofilm cells of Streptococcus mutans. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 205:139-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tatevossian, A., and C. T. Gould. 1976. The composition of the aqueous phase in human dental plaque. Arch. Oral Biol. 21:319-323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Van Alst, N. E., K. F. Picardo, B. H. Iglewski, and C. G. Haidaris. 2007. Nitrate sensing and metabolism modulate motility, biofilm formation, and virulence in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect. Immun. 75:3780-3790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.