Abstract

Bacteria are normally haploid, maintaining one copy of their genome in one circular chromosome. We have examined the cell cycle of laboratory strains of Lactococcus lactis, and, to our surprise, we found that some of these strains were born with two complete nonreplicating chromosomes. We determined the cellular content of DNA by flow cytometry and by radioactive labeling of the DNA. These strains thus fulfill the criterion of being diploid. Several dairy strains were also found to be diploid while a nondairy strain and several other dairy strains were haploid in slow-growing culture. The diploid and haploid strains differed in their sensitivity toward UV light, in their cell size, and in their D period, the period between termination of DNA replication and cell division.

In contrast to higher eukaryotes, bacteria are haploid (6, 19); i.e., they store their genetic information in a single chromosome, which is then duplicated during the cell cycle. If the growth rate is sufficiently low, bacteria are born with a single copy of the chromosome, which will then be duplicated before the bacterium divides.

There are a few reports about bacteria that have more than one genome per cell, i.e., that are polyploid. Deinococcus radiodurans has been shown to have 4 to 10 copies of its genome (13, 14). The diplococcal bacterium Neisseria gonorrhoeae was found to be diploid per coccal unit (31). Azotobacter vinelandii bacteria amplify the genome during growth in rich medium more than 40 times (20, 24, 27). The giant bacterium Epulopiscium fishelsoni has been shown to amplify its genome into a polytene chromosome of 3,000-fold ploidy (2). In addition, noncomplementing diploid bacteria have been isolated from protoplast fusions in Bacillus subtilis (11) and, as a result of zygogenesis, in Escherichia coli (10). A few other bacteria with two to six different chromosomes have been reported (15, 30).

The normal cell cycle is divided into three periods: (i) the B period from cell division until initiation of replication, (ii) the C period in which the cell replicates its DNA, and (iii) the D period from termination of productive replication until cell division. The D period thus includes processes such as proofreading and deconcatenation. The B period is found only in cells whose generation times exceed the length of the combined C and D periods. If the generation times become shorter than the combined lengths of the C and D periods, then the initiations of replication move into previous cell cycles (16). Fast-growing bacteria will therefore have more than one ongoing round of DNA replication at the same time; they might have 4, 8, or even 16 origins of replication (4). Normal haploid cells are born with one chromosome, either replicating or nonreplicating, and always with one terminus of replication. Not until the replication has ended do the cells have two termini. If the D period becomes longer than the generation time, which happens at high growth rates, the cells will be born with two termini as a result of the overlapping cell cycles. Long D periods are discussed further in the Discussion.

We have examined the cell cycle of Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris MG1363 in order to determine the cell cycle periods. To our surprise, we found that slow-growing cultures of these bacteria were born with two complete chromosomes, which were replicated into four chromosomes during the C period. This strain thus fulfills the criterion of being diploid without overlapping chromosomal replication cycles. Comparison with other L. lactis strains showed that both of the subspecies, L. lactis subsp. cremoris and L. lactis subsp. lactis, had members that were either diploid, like MG1363, or haploid, like most bacteria.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and growth conditions.

The L. lactis strains used are listed in Table 1. Bacteria were grown in defined SA medium supplemented with glucose; in improved defined SALN medium (SA medium supplemented with adenosine, guanosine, uridine, cytosine, inosine, and thymidine at 20 mg/liter and lipoic acid at 2 mg/liter) (29) supplemented with either glucose, maltose, or galactose; or in minimal medium (MM), which is similar to SA medium but contains only glutamic acid at 0.3 g/liter as well as isoleucine, leucine, methionine, glutamine, and valine at 0.1 g/liter, histidine at 0.05 g/liter and which is supplemented with either glucose, maltose, galactose, or xylose. The minimal medium was improved by the addition of arginine (R) at 0.2 g/liter, asparagine (N) at 0.1 g/liter, or lipoic acid at 2 mg/liter when needed. Sugars were always added at 0.5%.

TABLE 1.

Strains used

| Strain | Reference | Diploid or haploida | Dairy or nondairy |

|---|---|---|---|

| L. lactis subsp. cremoris strains | |||

| MG1363 | 9 | Diploid | Dairy |

| ED79.1175b | 5 | Diploid | Dairy |

| NCDO0712 | 9 | Diploid | Dairy |

| NCDO2031 | 18 | Haploid | Dairy |

| NCDO0505 | 18 | Haploid | Dairy |

| L. lactis subsp. lactis strains | |||

| IL1403 | 3 | Diploid | Dairy |

| IL-594 | 3 | Diploid | Dairy |

| CHCC373 | 26 | Haploid | Dairy |

| NCDO2118 | 8 | Haploid | Nondairy |

This work.

Derivative of MG1363; pyrDa pyrDb mutant.

E. coli was grown in MOPS (morpholinepropanesulfonic acid) medium (25) supplemented with either alanine or proline at 0.5% or glycerol at 0.1% as a carbon energy source.

Flow cytometry.

Flow cytometry was done as described previously (22).

Single cells.

Single cells were obtained by vigorous shaking as described previously (22).

Radioactive measurement of the DNA.

Cultures of ED79.1175 were grown in MM supplemented with uracil (10 mg/liter), lipoic acid, and glucose and either arginine or arginine plus asparagine. At an optical density at 450 nm (OD450) of 0.3 to 0.4, [14C]uracil at 0.4 μCi/ml was added. Incorporation into DNA was determined after the RNA was hydrolyzed with NaOH (12). The specific incorporation into DNA per OD450 unit was determined as the slope of counts against the OD450, and the average amounts of DNA per cell in the cultures were calculated based on the specific activity of the [14C]uracil in the cultures and on the determined number of single cells per 1 ml (5.4 × 108 cells at an OD450 of 1). Cell numbers were obtained as the number of CFU from parallel cultures after vigorous shaking to break up chains of cells.

Flow cytometric DNA histograms were made from parallel cultures. The DNA content in the cells from the B period was calculated, assuming that the actual distributions of DNA in the cultures were identical to the flow cytometric distributions and, thus, that the ratios between the average DNA content and the content of the cells in the B period were identical.

Fluorescence microscopy.

For quantification of the DNA content, the cells were stained for DNA with Hoechst 33342 at 0.1 μg per ml and examined in the microscope. Cellular fluorescence was quantitated and taken as a measure of the amount of DNA in the cell. For visualization of the nucleoids, the cells were stained with Hoechst 33342 at 0.5 μg per ml.

Enzyme assays.

Enzyme assays were done as described previously (7). The specific activities were calculated as enzyme activities per unit of protein. Protein concentrations were calculated from OD280 measurements. The specific activities of MG1363 were set at 1.

Sensitivity toward UV.

The strains were grown in MM supplemented with glucose and lipoic acid. Ten milliliters of each culture was exposed to UV light in a petri dish while the dish was shaken. Every 30 s samples were withdrawn and iced in the dark. They were then vigorously shaken to obtain single cells, plated on M17 medium supplemented with glucose, and incubated in the dark.

Simulation of models with single-hit or two-hit killing of the cells.

In a small computer model program, 105 cells were randomly hit in rounds of 3 × 104 hits. After each round, the number of survivors was counted. For the model with single-hit killing, a survivor was defined as a cell without any hit, and for the model with two-hit killing a survivor was a cell hit at most once.

To adapt the simulation to the actual data in Fig. 6, the numbers of survivors were multiplied by 20, and the model “time” (equal to the number of calculation rounds) was normalized to the time scale of the actual UV killings.

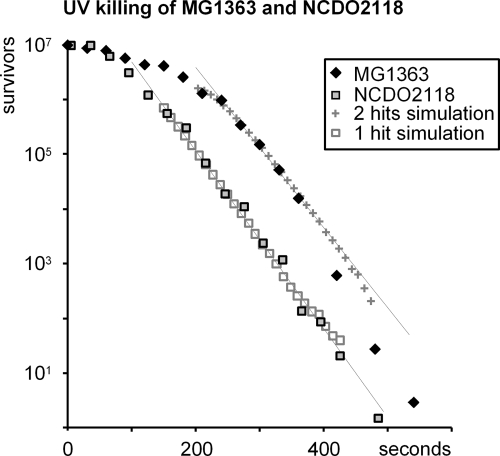

FIG. 6.

UV killing of MG1363 and NCDO2118. The strains were grown in MM supplemented with glucose and lipoic acid. The generation times for MG1363 and NCDO2118 were 264 min and 154 min, respectively. Half-lives for UV-exposed NCDO2118 and MG1363 were 19 and 21 s, respectively. Simulations in which one (NCDO2118) or two (MG1363) hits were needed for killing the bacteria, have been fitted to the curves. The number of survivors has been normalized. Actual starting numbers were 1.2 × 107 and 2.2 ×107 cells per ml for MG1363 and NCDO2118, respectively.

RESULTS

MG1363 and IL1403 are diploid in slow-growing cultures.

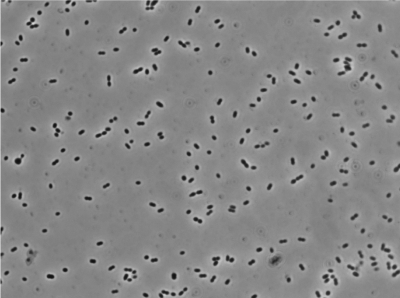

Flow cytometry was used to determine the cellular DNA content and the cell size (light scatter) (28) in slow-growing cultures of the standard laboratory strain L. lactis subsp. cremoris MG1363, which grew with a generation time of 228 min in MM supplemented with glucose and lipoic acid. Since L. lactis is known to form chains of cells, the chains were broken by vigorous shaking prior to the flow cytometry. We also examined the samples under the microscope and found that more than 90% of the bacteria were present as single cells (Fig. 1). The remaining objects in Fig. 1 are cells that were just about to divide or had just divided, and less than 5% of the cells were present as two or more cells stuck together in chains. The analysis was thus done on single cells and not cells in chains. The DNA histograms obtained by flow cytometry (Fig. 2) exhibited two maxima of nonreplicating cells interconnected with a ridge of replicating cells. The two peaks represent cells in the B and D periods, respectively, as they are not engaged in DNA replication. The replicating cells represent cells in the C period (4). The B period is the time from division until initiation of chromosome replication, and the D period is the time from termination of chromosome replication until cell division. The histograms were resolved to reveal the number of cells in each of the three cell cycle periods and thus the length of the periods. For controls, we also performed flow cytometry on slow-growing E. coli cells that are known to contain only one chromosome in the B period (23). To our surprise, we found that the DNA content of L. lactis cells in the B period was very close to the DNA content of the E. coli cells in the B period. Since the genome size of E. coli is 4.64 Mbp (1) and the genome size of L. lactis subsp. cremoris MG1363 is 2.53 Mbp (32), this observation strongly indicated that newborn L. lactis subsp. cremoris cells contained twice as much DNA as expected for a haploid bacterium. The same result was obtained with the other widely used laboratory strain L. lactis subsp. lactis IL1403. These two strains thus fulfill the criterion for being diploid in these slow-growing cultures.

FIG. 1.

Phase-contrast micrograph of the cells that were used for the flow cytometry experiment shown in Fig. 2.

FIG. 2.

Flow cytometric DNA histograms of L. lactis subsp. cremoris MG1363 grown in MM supplemented with glucose and lipoic acid at a generation time of 228 min and of E. coli grown with proline as a carbon source. The DNA histograms were resolved into B, C, and D periods. The two samples were recorded with the same settings. D′ is the D period minus the generation time.

Cells from the same slow-growing culture of L. lactis subsp. cremoris MG1363 were stained with Hoechst 33342 and examined under the fluorescence microscope. The histogram of the DNA in the cells was found to overlay the flow cytometric histogram after normalization of the different fluorescence scales used (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). This supports the conclusion that the histograms were obtained with single cells and not with cells in chains.

Because the above results were based on comparison of stained Gram-positive bacteria with stained Gram-negative bacteria, we compared the staining efficiency of E. coli and B. subtilis cells. These two bacteria have chromosomes of almost identical sizes (4.64 and 4.21 Mbp, respectively) but have a different GC content (51% and 44%, respectively) while L. lactis subsp. cremoris MG1363 has a GC content of 36%. E. coli and B. subtilis DNA was stained to the same extent (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material), which supports the idea that the DNA of L. lactis subsp. cremoris MG1363 was stained similarly.

Radioactive measurements of the DNA in the cells confirm that MG1363 is diploid.

To check the flow cytometric results with a different method, cultures of ED79.1175 (a pyrDa pyrDb double mutant of MG1363 mutated in both orotate dehydrogenases and thus unable to synthesize uracil) growing in MM supplemented with glucose and lipoic acid and either arginine or arginine and asparagine were labeled with [14C]uracil. The DNA content of the cells in the B period was calculated from the labeling data as described in Materials and Methods (Table 2). From these measurements it can be seen that the B period cells contained 4.64 ± 0.44 Mbp of DNA, and therefore the average DNA content of the B period cells was 1.8 ± 0.2 genomes per cell. These results corroborate the flow cytometric results that this bacterium, indeed, is born with two nonreplicating chromosomes in slow-growing cultures.

TABLE 2.

Radioactive measurements of genomes per newborn ED79.1175 cell

| No. of genomes/cell under the indicated conditiona | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Expt 1 |

Expt 2 |

||

| R | R + N | R | R + N |

| 1.72 | 1.67 | 2.05 | 1.86 |

| 1.67 | 1.67 | 2.05 | 1.84 |

| 1.67 | 1.62 | 2.07 | 1.84 |

| 1.80 | 1.70 | 2.16 | 1.96 |

Cells were grown in MM supplemented with 0.5% glucose and either arginine (R) or both arginine and asparagine (R + N). Under both conditions the average number of genomes/cell was 1.8 (4.64 Mbp) with a standard deviation of 0.2 genomes/cell (0.44 Mbp).

Ploidy of different L. lactis strains.

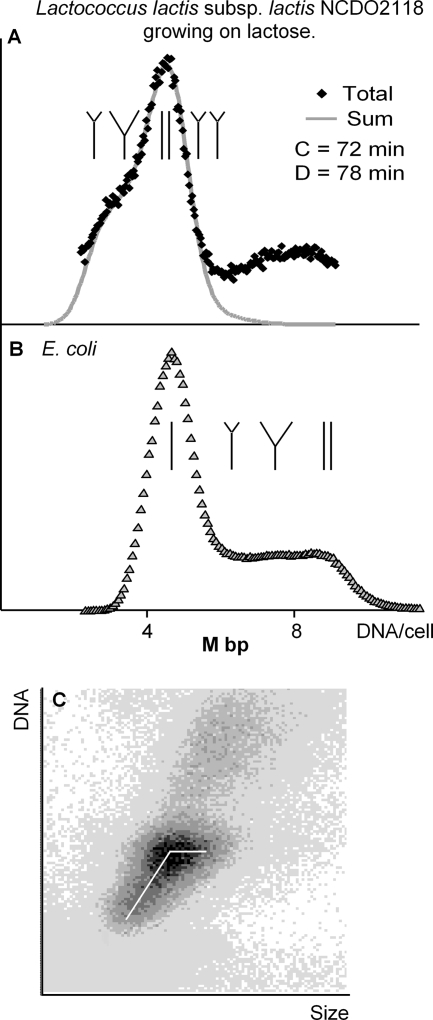

To test if diploidy is a general phenomenon in L. lactis strains, we decided to analyze L. lactis subsp. lactis NCDO2118, a natural nondairy isolate of Lactococcus. The strain was grown in MM supplemented with arginine and lactose. Figure 3 shows the flow cytometric DNA histogram (panel A) together with a flow-cytometric cytogram of DNA content versus size of the cells (panel C). For comparison, a flow-cytometric DNA histogram of an E. coli strain grown with proline as a carbon energy source (panel B) was included. In Fig. 3A, it is seen that strain NCDO2118 was initiating the DNA replication just prior to division and was born with one replicating chromosome. The DNA replication was finished 60 min after division, and the cells then contained two nonreplicating chromosomes until 10 min before division. From Fig. 3 it can also be seen that the cells with nonreplicating chromosomes of strain NCDO2118 have amounts of DNA equal to amounts in E. coli cells with one chromosome. The cells of strain NCDO2118 were thus born with one chromosome with one terminus of replication, and therefore, they fulfill the criterion for being haploid. We also analyzed some dairy strains including NCDO712 and IL-594 which are mother strains for the two diploid laboratory strains, MG1363 and IL1403, respectively. The strains were grown in MM supplemented with glucose and arginine, and samples were withdrawn and examined in the flow cytometer. Cells that had a clear B period with two chromosomes were considered diploid while those that were born with one replicating chromosome were considered haploid. The two mother strains were also found to be diploid. Thus, diploidy was not a result of the previous curing of the laboratory strains for plasmids and phages (9). The results are summarized in Table 1.

FIG. 3.

(A) A flow cytometric DNA histogram of haploid L. lactis subsp. lactis NCDO2118 growing at a generation time of 139 min. The histogram has been resolved for cell cycle periods. The status of chromosomal replication is also indicated on this panel (from left to right): just initiated, replicating, nonreplicating, and just initiated. The cells to the right in the histogram are cells that stick together. These cells can be seen as a shadow in the upper part of the cytogram in panel C. (B) A flow cytometric DNA histogram of an E. coli strain growing on proline as a carbon energy source and recorded at the same settings as the histogram in panel A. The status of chromosomal replication is also indicated on this panel (from left to right): nonreplicating, just initiated, replicating, and nonreplicating. (C) A flow cytometric cytogram of DNA versus size of the NCDO2118 culture. The white line indicates the change in DNA content and growth of each cell in the culture.

Visualization of the diploidy of MG1363.

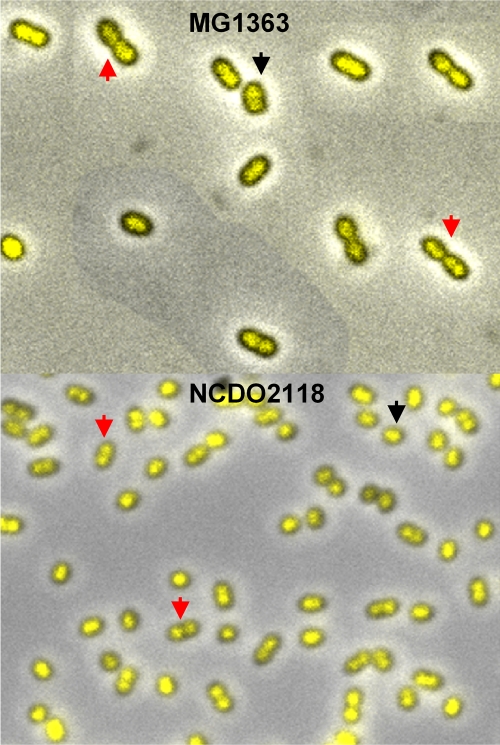

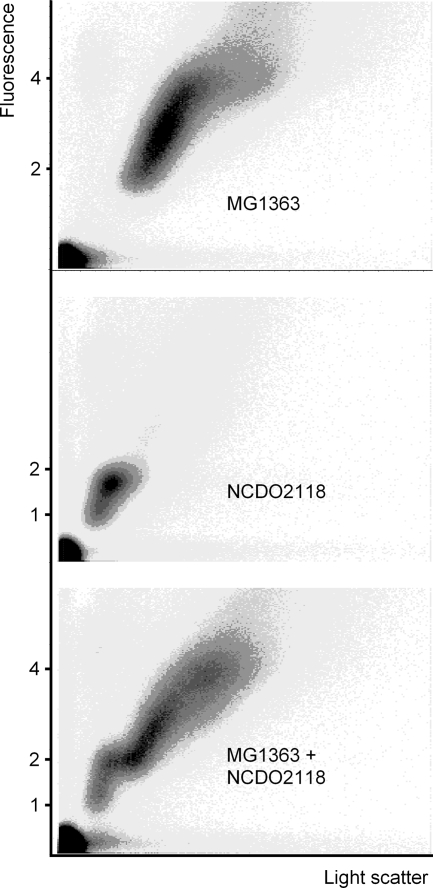

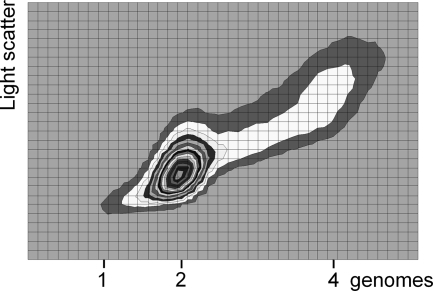

Cells from MG1363 and NCDO2118 growing in MM supplemented with glucose and arginine with generation times of 125 and 161 min, respectively, were stained with 0.5 μg of Hoechst 33342 per ml and examined under the fluorescence microscope. Figure 4 shows cells just about to divide from the MG1363 and NCDO2118 cultures with four and two nucleoids, respectively, together with newly born cells with two and one nucleoid, respectively. On the same figure it can be seen that MG1363 cells were larger than NCDO2118 cells. Cells from the same culture were examined in the flow cytometer both individually and together using the same settings on the instrument. The flow cytometric cytograms in Fig. 5 show that the mass of the cells from the MG1363 culture was about twice the mass of the cells from the NCDO2118 culture. The cytograms also show that the amounts of DNA in the cells in the two cultures were different. If the amounts of DNA in the NCDO2118 cells were set to vary from 1 to 2, then the amounts of DNA in the MG1363 cells varied from 2 to 4, as would be expected in a diploid strain.

FIG. 4.

Fluorescence micrograph of MG1363 and NCDO2118 from slow-growing cultures with generation times of 126 min and 161 min, respectively. Red arrows indicate cells about to divide with four (MG1363) or two (NCDO2118) nucleoids. Black arrows indicate new-born cells with two nucleoids (MG1363) or one (NCDO2118) nucleoid.

FIG. 5.

Flow cytometric cytograms of cells from slow-growing cultures of L. lactis subsp. cremoris MG1363 and L. lactis subsp. lactis NCDO2118 growing with 125-min and 161-min generation times, respectively. The cytograms were recorded with the same settings on the instrument. Numbers along the y axis indicate the number of genomes.

Differences between the diploid MG1363 and haploid NCDO2118 strains.

A property which may be expected to differ between haploid and diploid strains is the sensitivity toward UV irradiation. We measured these sensitivities for diploid MG1363 and haploid NCDO2118 strains toward increased doses of UV light and found that for both strains there was a shoulder in the kill curves before the strains started to die off (Fig. 4). The shoulder of MG1363 was close to twice the length (approximately 170%) of that of NCDO2118 while the apparent half-lives in the death phase were almost identical for the two strains. Furthermore, the haploid NCDO2118 strain was killed with the expected zero-order kinetics found for other (haploid) bacteria while the kinetics for the diploid MG1363 was different from the zero order and instead fitted a model where each bacterium had to acquire two hits to be killed (Fig. 6). The diploid strain thus seemed to be more resistant to UV irradiation than the haploid strain.

In order to see if there were any differences in gene expression between haploid (NCDO2118) and diploid (MG1363) strains, we determined the activities of three glycolytic enzymes and found that the specific activities (enzyme units/OD280 [protein]) of the three enzymes were relatively constant (Table 3). However, our flow cytometry data revealed that the light scatter from the haploid NCDO2118 cells was about half of the light scatter from the diploid MG1363 cells. Determination of the number of CFU per ml at comparable growth rates of MG1363 and NCDO2118 at an OD600 of 1 gave 3.3 × 108 and 7.8 × 108, respectively. This shows that the volume of a haploid cell is approximately half the volume of a diploid cell; and if we therefore look at the activities per cell, we find the 2-fold difference which would be expected between haploid and diploid strains.

TABLE 3.

Enzyme activity of three glycolytic enzymes in the diploid MG1363 strain and the haploid NCDO2118 strain growing at compatible growth ratesa

| Enzyme and strain | Relative specific activityb | Relative activity/cellc |

|---|---|---|

| Trioseisomerase | ||

| MG1363 | 1.00 | 1.0 |

| NCDO2118 | 0.89 | 0.4 |

| Aldolase | ||

| MG1363 | 1.00 | 1.0 |

| NCDO2118 | 1.17 | 0.5 |

| Phosphofructokinase | ||

| MG1363 | 1.00 | 1.0 |

| NVDO2118 | 0.76 | 0.3 |

The generation times were 138 min for MG1363 and 168 min for NCDO2118.

Activity per OD280 (protein) unit relative to the activity of MG1363.

Corrected for cell number/ml at OD600 of 1.000; the number of CFU of NCDO2118 per ml/number of CFU of MG1363 per ml = 2.4.

Cell cycle periods for MG1363 and NCDO2118 at different growth rates.

In the study described above, we grew the MG1363 and NCDO2118 strains in several types of minimal media with different additions of amino acids as well as different carbon sources, which resulted in different growth rates. As the preliminary results indicated that the apparent D periods became very short in faster-growing cultures, we extended this study with growth in SA and SALN media supplemented with different sugars in order to examine the cell cycle parameters at even higher growth rates.

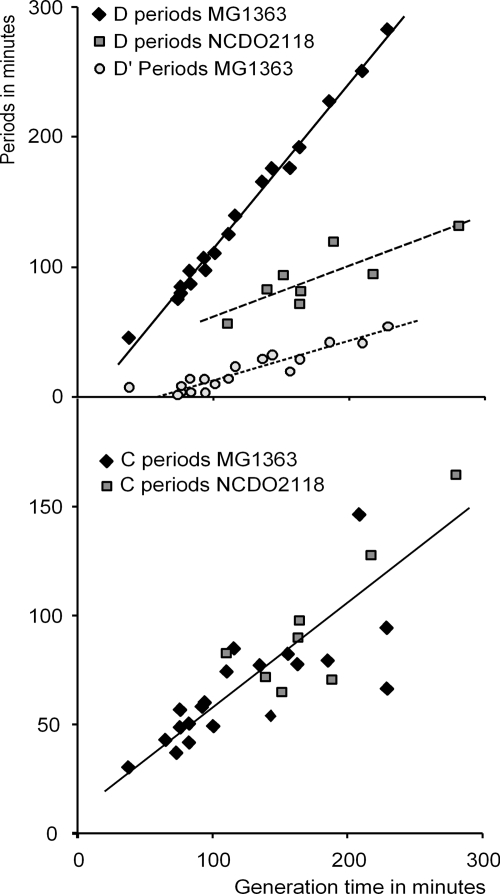

Cells from these cultures were examined in the flow cytometer, and the DNA histograms were resolved as described previously (23). The D period from the slow-growing cultures of MG1363 increased linearly with generation time and extrapolated toward 0 min at a generation time around 60 min (Fig. 7, open circles). A number of processes have to take place in the D period: the newly replicated chromosomes should be resolved, the chromosome should be segregated to the two halves of the cell which become the new daughter cells, the division septum should be formed aided by the formation of the ftsZ ring, and the cell should start the division process. Performing all of these processes is not compatible with a D period of zero minutes. Therefore, we propose that the D periods first determined for the slow-growing cells were apparent D periods (D′) and that the signals starting all of these processes were actually initiated in the previous cell cycle. Thus, the true D period equals the D′ period plus the generation time (Fig. 7, diamonds). The D period is defined as the period from termination of chromosome replication until cell division. If the D period is longer than the generation time, it would result in cells that are born with two termini. We conclude that strain MG1363 is diploid at all growth rates. The D period for the other diploid laboratory strain, IL1403, has been determined for a generation time of 100 min and was found to be compatible with values of MG1363 with a generation time close to 100 min (data not shown). The D periods of NCDO2118 growing at different generation times are also presented in Fig. 7. Newborn cells of NCDO2118 were found to have only one terminus; consequently, the D periods in this strain were shorter than the generation time.

FIG. 7.

Cell cycle periods D and C of MG1363 and NCDO2118. The periods have been determined by resolving flow cytometric DNA histograms of cultures grown at different generation times. See text for discussion of D′ versus D periods.

The C periods of both strains were identical and increased with the generation times, as found for other bacteria (23) (Fig. 7). It should be noted that the sum of the D and C periods for NCDO2118 at all growth rates analyzed—even at a generation time of 280 min—was higher than the generation time, implying that this strain did not have a B period under the circumstances examined here. In fact, B periods were not observed for any of the strains found to be haploid during the haploid-diploid screening.

DISCUSSION

Using flow cytometry, we have shown that the cell cycle of slowly growing cells of L. lactis subsp. cremoris MG1363 can be resolved into B, C, and D periods, similar to what has been done for the E. coli cell cycle (4, 17). The flow cytometric DNA histogram of L. lactis subsp. cremoris MG1363 revealed to our surprise that the cells in the B period had a fluorescence signal equal to the fluorescence signal of B period cells from slow-growing E. coli cultures. This strongly suggests that the cells in the B period contained two complete chromosomes as the size of an MG1363 chromosome is 2.53 Mbp, which is close to half the size of the E. coli chromosome (4.64 Mbp). This finding was confirmed by a direct determination of the amount of DNA in the cells by radioactive labeling.

Phase contrast microscopy of samples from the slow-growing cultures showed that the majority of the cells were present as single cells or as cells that were about to divide, which rules out the possibility that cells were present in short chains with two cells. Further evidence came from the fact that MG1363 was more resistant to UV light than the haploid NCDO2118. The kill curve for NCDO2118 followed the normal zero-order genetics expected for haploid bacteria while the kill curve for MG1363 followed a kinetic model requiring two hits to kill.

When cells from cultures of MG1363 and NCDO2118 growing with comparable growth rates were examined under the fluorescence microscope, the MG1363 cells revealed a few cells just about to divide, having four nucleoids, together with newborn cells with two nucleoids. In contrast, the NCDO2118 cells showed cells just about to divide, with two nucleoids and newborn cells with one nucleoid. When the same cells were examined in the flow cytometer individually and together, the cytograms clearly showed that the cells occupied different areas in the cytograms, that the MG1363 cells were twice the size of the NCDO2118 cells, and that the amounts of DNA in the NCDO2118 cells varied from 1 to 2 while the amounts of DNA in the MG1363 cells varied from 2 to 4.

Examination of the cell cycle periods for both MG1363 and NCDO2118 showed that the periods increased with increasing generation times. The D periods of MG1363 were longer than the generation times, and thus MG1363 has overlapping D periods (Fig. 7). The D periods of NCDO2118 were shorter than the generation times, as expected. The C periods of both strains were identical and increased with increasing generation time. None of the examined haploid strains had B periods under the conditions used.

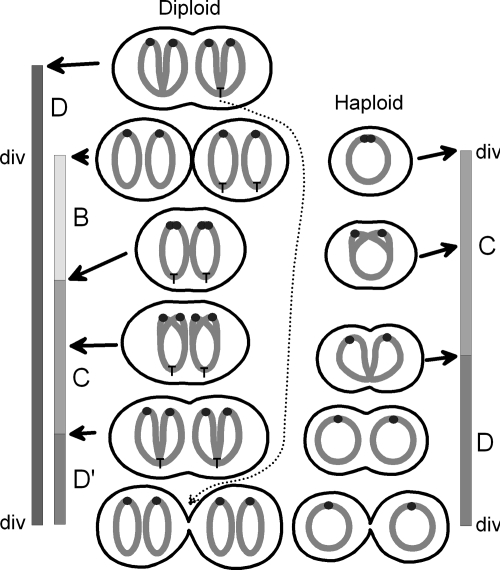

Normally, bacteria are born with one chromosome with one terminus unless they have overlapping D periods, as is seen in very fast-growing bacteria. Diploid bacteria such as MG1363 are born with two chromosomes with two termini and have overlapping D periods as those termini that are formed in one cell cycle do not segregate until the next cell cycle (Fig. 8).

FIG. 8.

The cell cycles of diploid (MG1363) and haploid (NCDO2118) L. lactis strains. The cell cycle from division (div) to division consists of a B period, a C period, and a D′ period. The chromosomes are shown as dark-gray open figures, with the replication start points (origins) represented as solid black circles. The diploid cell cycle of the MG1363 strain is shown to the left. The replication end points (termini) that are split at division in the bottom of the figure are those formed after replication of the terminus (denoted with T in the top cell), as indicated with the dotted line. The haploid cell cycle of NCDO2118 is shown to the right. Initiation of replication occurs simultaneously with cell division. Consequently, this strain has no B period.

These experimental findings justify the conclusion that L. lactis subsp. cremoris MG1363 bacteria are born with two chromosomes, and thus the strain is diploid.

The term diploid should be reserved for those strains that are born with two chromosomes, defined as a single element, either nonreplicating or replicating, and with only one terminus of replication. A chromosome might thus have 2n replication origins (0 ≤ n ≤ 4), depending on the number of overlapping rounds of replication.

Examination of other L. lactis strains showed that some strains are diploid, including the other widely used laboratory strain L. lactis subsp. lactis IL1403 and dairy strains NCDO0712 and IL-594 from which MG1363 and IL1403 are derived. Other dairy strains were either diploid or haploid, and the nondairy strain NCDO2118 was haploid.

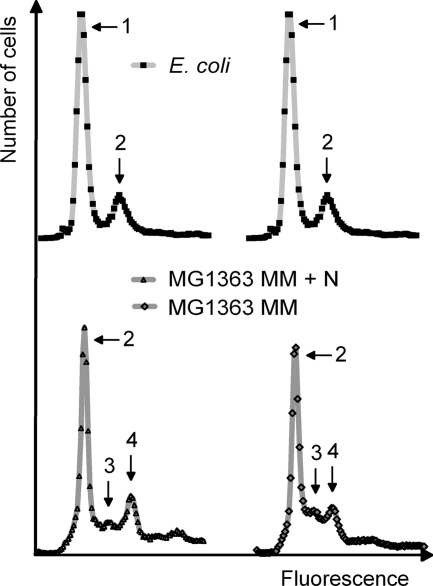

Careful examination of the flow cytometric DNA histograms in Fig. 2 and other DNA histograms (Fig. 9) revealed a minor peak at a position of three chromosomes. These peaks of cells with amounts of DNA equal to three chromosomes could not be fitted as bacteria-replicating DNA. When cells pile up in the flow cytometric DNA histograms, it means that these cells have either finished their DNA replication or paused the replication process. It seems more likely that these cells with an amount of DNA corresponding to three genomes have finished DNA replication than that they would have paused their DNA replication just half way through the chromosomes. The presence of these cells therefore indicates that occasionally cells initiate DNA replication on only one of the two chromosomal origins of replication, thus giving rise to cells with three chromosomes. Furthermore, upon division such cells with three chromosomes should give rise to one cell with two chromosomes and one with one chromosome. Careful reexamination of DNA histograms (Fig. 2 and 9) and of DNA cytograms (Fig. 10) revealed a small fraction of cells with a DNA content of less than two genomes. In the DNA cytograms these cells are interpreted as engaged in replication as they are seen as a broad distribution from one to two genome amounts of DNA. These cells presumably initiate replication just after division because they are born with a cell mass compatible with cells with two chromosomes. This replication takes place immediately after cell division without a proportional increase in light scatter. After the chromosome has been replicated, these cells seem to integrate in the normal pool of cells with two chromosomes (Fig. 10). The presence of such cells is thus compatible with the assumption that these cells normally are born with two complete chromosomes.

FIG. 9.

Flow cytometric DNA histograms of L. lactis subsp. cremoris MG1363 grown at different generation times (in MM plus N, generation time is 143 min; in MM, generation time is 185 min panel) and of E. coli (with two identical histograms). E. coli was grown with proline as a carbon source and incubated with rifampin and cephalexin for 4 h; the histograms show cells with 1 and 2 chromosomes. Rifampin inhibits initiation of replication but not elongation. E. coli treated with rifampin thus terminates ongoing replication and ends with completely replicated chromosomes. Cephalexin inhibits cell division and thus prevents those cell divisions that otherwise would occur in the presence of rifampin. Arrows numbered 1 to 4 correspond to peaks representing 1 to 4 chromosomes, respectively.

FIG. 10.

Flow cytometric cytogram of the cells shown in Fig. 2. Concomitant increases in mass (light scatter) and DNA (fluorescence) can be seen.

The occurrence of diploidy in some dairy strains—in contrast to the haploid wild-type L. lactis, represented by NCDO2118—suggests that diploidy has been selected for during the 5 to 10 thousand years lactococci have been used in cheese production. The reasons for this selection are unknown, but it seems likely that diploidy results from an active selection either for a desirable aroma or for faster acidification or possibly for other reasons. For the other known polyploid bacteria, various reasons have been suggested. The polyploidy of D. radiodurans has been suggested to be important in repair of double-strand breaks and thus necessary for the high radiation resistance characteristic of this bacterium. The polyploidy of N. gonorrhoeae, which possesses one of the most potent pilin-antigenic diversity variations, is probably important for the mechanism by which this variation takes place through recombination (31). Furthermore, N. gonorrhoeae bacteria lacking the SOS response may have supplanted the need for an inducible repair system by being polyploid (31). The genome amplification of A. vinelandii is probably followed by cyst formation in the late lag phase after growth has ceased. However, A. vinelandii, which has a genome size of 5.4 Mbp, does not amplify its genome when grown in a minimal medium as this slow growth rate does not support formation of cysts. A DNA histogram obtained by flow cytometry from cells grown in minimal medium resembles a DNA histogram of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, with a genome size of 4.9 Mbp (21), grown under similar conditions (20).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Danish Dairy Research Foundation.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 22 December 2009.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Blattner, F. R., G. Plunkett, III, C. A. Bloch, N. T. Perna, V. Burland, M. Riley, J. Collado-Vides, J. D. Glasner, C. K. Rode, G. F. Mayhew, J. Gregor, N. W. Davis, H. A. Kirkpatrick, M. A. Goeden, D. J. Rose, B. Mau, and Y. Shao. 1997. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science 277:1453-1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bresler, V., and L. Fishelson. 2003. Polyploidy and polyteny in the gigantic eubacterium Epulopiscium fishelsoni. Mar. Biol. 143:17-21. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chopin, A., M. C. Chopin, A. Moillo-Batt, and P. Langella. 1984. Two plasmid-determined restriction and modification systems in Streptococcus lactis. Plasmid 11:260-263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cooper, S., and C. E. Helmstetter. 1968. Chromosome replication and the division cycle of Escherichia coli B/r. J. Mol. Biol. 31:519-540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Defoor, E., M. B. Kryger, and J. Martinussen. 2007. The orotate transporter encoded by oroP from Lactococcus lactis is required for orotate utilization and has utility as a food-grade selectable marker. Microbiology 153:3645-3659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dykhuizen, D. E. 1990. Experimental studies of natural-selection in bacteria. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 21:373-398. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Even, S., N. D. Lindley, and M. Cocaign-Bousquet. 2001. Molecular physiology of sugar catabolism in Lactococcus lactis IL1403. J. Bacteriol. 183:3817-3824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farrow, J. A. E. 1980. Lactose hydrolysing enzymes in Streptococcus lactis and Streptococcus cremoris and also in some other species of streptococci. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 49:493-503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gasson, M. J. 1983. Plasmid complements of Streptococcus lactis NCDO 712 and other lactic streptococci after protoplast-induced curing. J. Bacteriol. 154:1-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gratia, J. P. 2005. Noncomplementing diploidy resulting from spontaneous zygogenesis in Escherichia coli. Microbiology 151:2947-2959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guillen, N., M. H. Gabor, R. D. Hotchkiss, and L. Hirschbein. 1982. Isolation and characterization of the nucleoid of non-complementing diploids from protoplast fusion in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Gen. Genet. 185:69-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hansen, F. G., and K. V. Rasmussen. 1977. Regulation of the dnaA product in E. coli. Mol. Gen. Genet. 155:219-225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hansen, M. T. 1978. Multiplicity of genome equivalents in the radiation-resistant bacterium Micrococcus radiodurans. J. Bacteriol. 134:71-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harsojo, S. Kitayama, and A. Matsuyama. 1981. Genome multiplicity and radiation resistance in Micrococcus radiodurans. J. Biochem. 90:877-880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heidelberg, J. F., J. A. Eisen, W. C. Nelson, R. A. Clayton, M. L. Gwinn, R. J. Dodson, D. H. Haft, E. K. Hickey, J. D. Peterson, L. Umayam, S. R. Gill, K. E. Nelson, T. D. Read, H. Tettelin, D. Richardson, M. D. Ermolaeva, J. Vamathevan, S. Bass, H. Qin, I. Dragoi, P. Sellers, L. McDonald, T. Utterback, R. D. Fleishmann, W. C. Nierman, O. White, S. L. Salzberg, H. O. Smith, R. R. Colwell, J. J. Mekalanos, J. C. Venter, and C. M. Fraser. 2000. DNA sequence of both chromosomes of the cholera pathogen Vibrio cholerae. Nature 406:477-483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Helmstetter, C. E. 1996. Timing of synthetic activities in the cell cycle, p. 1627-1639. In F. C. Neidhardt, R. Curtiss, J. L. Ingraham, J. L. Lin, K. B. Low, B. Magasanik, W. S. Reznikoff, M. Riley, M. Schaechter, and H. E. Umbarger (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium cellular and molecular biology. ASM, Washington, DC.

- 17.Helmstetter, C. E., and O. Pierucci. 1976. DNA synthesis during the division cycle of three substrains of Escherichia coli B/r. J. Mol. Biol. 102:477-486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Le Bourgeois, P., M. L. Daveran-Mingot, and P. Ritzenthaler. 2000. Genome plasticity among related Lactococcus strains: identification of genetic events associated with macrorestriction polymorphisms. J. Bacteriol. 182:2481-2491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levin, B. R., and C. T. Bergstrom. 2000. Bacteria are different: observations, interpretations, speculations, and opinions about the mechanisms of adaptive evolution in prokaryotes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:6981-6985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maldonado, R., J. Jimenez, and J. Casadesus. 1994. Changes of ploidy during the Azotobacter vinelandii growth cycle. J. Bacteriol. 176:3911-3919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McClelland, M., K. E. Sanderson, J. Spieth, S. W. Clifton, P. Latreille, L. Courtney, S. Porwollik, J. Ali, M. Dante, F. Du, S. Hou, D. Layman, S. Leonard, C. Nguyen, K. Scott, A. Holmes, N. Grewal, E. Mulvaney, E. Ryan, H. Sun, L. Florea, W. Miller, T. Stoneking, M. Nhan, R. Waterston, and R. K. Wilson. 2001. Complete genome sequence of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium LT2. Nature 413:852-856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Michelsen, O., A. Cuesta-Dominguez, B. Albrechtsen, and P. R. Jensen. 2007. Detection of bacteriophage-infected cells of Lactococcus lactis by using flow cytometry. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:7575-7581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Michelsen, O., M. J. Teixeira de Mattos, P. R. Jensen, and F. G. Hansen. 2003. Precise determinations of C and D periods by flow cytometry in Escherichia coli K-12 and B/r. Microbiology 149:1001-1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nagpal, P., S. Jafri, M. A. Reddy, and H. K. Das. 1989. Multiple chromosomes of Azotobacter vinelandii. J. Bacteriol. 171:3133-3138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neidhardt, F. C., P. L. Bloch, and D. F. Smith. 1974. Culture medium for enterobacteria. J. Bacteriol. 119:736-747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pedersen, M. B., P. R. Jensen, T. Janzen, and D. Nilsson. 2002. Bacteriophage resistance of a ΔthyA mutant of Lactococcus lactis blocked in DNA replication. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:3010-3023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pulakat, L., S. H. Lee, and N. Gavini. 2002. Genome of Azotobacter vinelandii: counting of chromosomes by utilizing copy number of a selectable genetic marker. Genetica 115:147-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Skarstad, K., H. B. Steen, and E. Boye. 1983. Cell cycle parameters of slowly growing Escherichia coli B/r studied by flow cytometry. J. Bacteriol. 154:656-662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Solem, C., B. J. Koebmann, F. Yang, and P. R. Jensen. 2007. The las enzymes control pyruvate metabolism in Lactococcus lactis during growth on maltose. J. Bacteriol. 189:6727-6730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Teyssier, C., H. Marchandin, and E. Jumas-Bilak. 2004. Le génome des alpha-protéobactéries: complexté, réduction, diversité et fluidité. Can. J. Microbiol. 50:383-396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tobiason, D. M., and H. S. Seifert. 2006. The obligate human pathogen, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, is polyploid. PLoS Biol. 4:e185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wegmann, U., M. O'Connell-Motherway, A. Zomer, G. Buist, C. Shearman, C. Canchaya, M. Ventura, A. Goesmann, M. J. Gasson, O. P. Kuipers, D. van Sinderen, and J. Kok. 2007. Complete genome sequence of the prototype lactic acid bacterium Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris MG1363. J. Bacteriol. 189:3256-3270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.