Abstract

A cell surface display system was developed using Escherichia coli OmpC as an anchoring motif. The fused Pseudomonas fluorescens SIK W1 lipase was successfully displayed on the surface of E. coli cells, and the lipase activity could be enhanced by the coexpression of the gadBC genes identified by transcriptome analysis.

Cell surface display is a technique for expressing target molecules fused to an anchoring motif on the surface of various host cells (2, 9, 15, 21, 22). This technique has numerous biotechnological applications, including vaccine development, antibody production, peptide library display and screening, bioremediation, bioadsorption, biocatalysis, and biosensor development.

We previously reported that lipase could be successfully displayed using FadL and OprF as anchoring motifs (12, 13, 14). When we displayed the Pseudomonas fluorescens SIK W1 lipase (TliA) on the surface of Escherichia coli W3110 (derived from prototropic strain K-12 λ− F−) by using these anchoring motifs, the lipase activity was very low. Thus, a new surface anchoring system was developed in this study.

For the efficient display of lipase, a C-terminal deletion fusion strategy using E. coli OmpC as an anchoring motif was first considered (23). Based on the predicted secondary structure and information found in literature (3, 11, 23), the truncated ompC gene encoding 288 amino acids from the N terminus was amplified and fused with the tliA gene (13; see also the supplemental methods). The fusion fragment was cloned into pTac99A (17) to make pTacOmpC288PL.

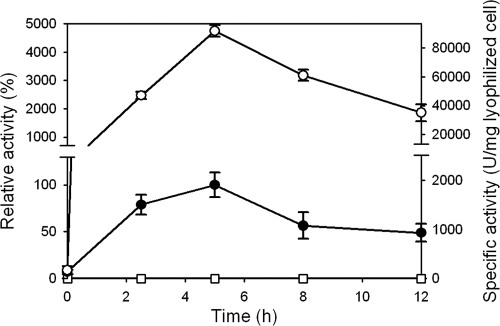

As expected, lipase activity was detected on the surface of E. coli cells harboring pTacOmpC288PL by using a spectrophotometric method (13; see also the supplemental methods) (Fig. 1). Compared with other lipase display systems, the lipase activity obtained with the OmpC display system was >10-fold higher than those obtained with OprF and FadL display systems; the specific activities were 1,940 ± 118, 172 ± 19, and 62 ± 13 U/mg lyophilized cells by the use of OmpC, OprF, and FadL as anchoring motifs, respectively. These results suggest that the C-terminal deletion fusion strategy using the E. coli OmpC as an anchoring motif provides an efficient way for displaying functional lipase on the surface of E. coli.

FIG. 1.

Activities of lipase displayed on the surface of E. coli W3110 cells harboring pTac99A (open squares), pTacOmpC288PL (closed circles), and pTacOmpC288PL plus pHNCgadBC (open circles). Relative activity was calculated by assuming the lipase activity of the strain harboring pTacOmpC288PL at 5 h as 100%.

For the enhanced display of lipase, transcriptome profiling was performed. All procedures, including RNA preparation, cDNA synthesis, DNA hybridization, and data analysis, were carried out as described previously (1; see also the supplemental methods). The transcriptome profiles of lipase-displaying cells and control cells at 5 h after IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) induction were compared. It was found that 1,165 out of 4,021 genes were differentially expressed by >2-fold (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). There is no general rule for selecting the gene amplification targets based on transcriptome profiling. However, one can select those genes that are significantly up- or downregulated as primary amplification targets, among which those relevant to possibly accomplishing the objective can be first tried (4, 18, 19).

Based on the transcriptome data, two operons, pspABCDE (1,924 bp) and gadBC (3,091 bp), containing the most up- and downregulated genes, were selected as target genes. It has been reported that the highly upregulated pspABCDE genes for phage shock proteins are related to protein export (5, 8). Thus, it seems that the expression levels of the pspABCDE genes are correlated with efficient secretion of lipase for its display on cell surface. On the other hand, the significantly downregulated gadBC genes are known to play an important role in glutamate decarboxylase-dependent acid tolerance (20). These target genes were coexpressed using pHNCpspABCDE and pHNCgadBC, respectively (see the supplemental methods). Recombinant E. coli W3110 harboring pTacOmpC288PL and pHNCpspABCDE exhibited 60.8% of the original lipase activity (Table 1). When the pspABCDE genes were deleted using the homologous recombination system (6), the lipase activity also decreased. Thus, the pspABCDE genes were not further considered target genes to be manipulated.

TABLE 1.

Effect of manipulating the target genes identified by transcriptome profiling on the specific activities of lipase displayed on the E. coli cell surface

| Target gene | Change in gene expression levels (log2)a | Lipase sp act (U/mg of lyophilized cells)b |

Relative lipase activity (%)c |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knockout strain | Amplification strain | Knockout strain | Amplification strain | ||

| pspABCDE | 2.4 to 5.8 | 1,110 ± 78 | 1,180 ± 78 | 57.2 ± 4.02 | 60.8 ± 4.02 |

| gadBC | −2.6 to −2.1 | 815 ± 83 | 92,300 ± 407 | 42.0 ± 4.28 | 4,760 ± 21.0 |

The values indicate the changes in the expression levels of the target genes in a recombinant E. coli strain displaying lipase compared with those of a control strain containing the backbone plasmid, determined by DNA microarray analysis.

One unit of lipase activity was defined as the amount of enzyme releasing 1 micromole of p-nitrophenol per minute. All measurements were independently performed in triplicates. The values after the ± sign represent the standard deviation.

Relative lipase activity was calculated by assuming the lipase activity measured in control strain without target gene manipulation (1,940 ± 118) as 100%.

In contrast, when the gadBC genes were coexpressed using pHNCgadBC, the lipase activity dramatically increased by 48-fold (Fig. 1, Table 1). The gadBC knockout strain harboring pTacOmpC288PL showed decreased lipase activity. To see if this positive effect is transferrable, the effect of GadBC coexpression on the lipase display using different anchoring motifs was examined. It was found that the lipase activities were increased by 2.51- and 1.59-fold for the display systems employing OprF and FadL, respectively; the specific activities were 432 and 98.6 U/mg lyophilized cells when using OprF and FadL anchoring motifs, respectively, with GadBC coexpression. Thus, these results indicate that GadBC coexpression might generally applicable for the enhanced display of lipase on the E. coli cell surface.

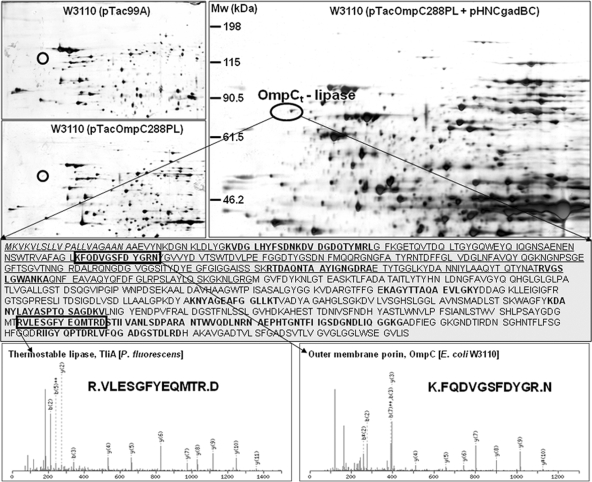

To validate the effect of GadBC coexpression on lipase display, transcript and protein level analyses were carried out. Real-time PCR was performed as described previously (1; see also the supplemental methods). It was found that the expression levels of the ompC and tliA genes were highly increased by >20-fold by GadBC coexpression. For protein level analysis, outer membrane proteins were isolated, separated, and identified using two-dimensional gel electrophoresis coupled with mass spectrometry, as reported previously (10, 13; see also the supplemental methods). As shown in Fig. 2, the OmpC-lipase fusion protein of ca. 83 kDa (pI 4.8) was detected, and the amount of the protein increased 15-fold when the gadBC genes were coexpressed. Thus, these results clearly suggest that GadBC coexpression improves the expression and display of the OmpC-lipase fusion protein.

FIG. 2.

Outer membrane proteome profiles obtained with E. coli W3110 harboring pTac99A, pTacOmpC288PL, and pTacOmpC288PL plus pHNCgadBC. Circles indicate the position of the truncated OmpC (OmpCt)-lipase fusion protein. The middle panel shows the amino acid sequence of lipase fused to OmpCt (underlined). The signal sequence is indicated in italics. The nonredundant peptide sequences identified by nano-liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC/MS/MS) are indicated in boldface type. The representative peptide sequences of lipase and OmpCt are shown in the bottom panels.

To examine whether biocatalytic ability is also enhanced by GadBC coexpression, enantioselective hydrolysis of 1-phenylethyl butyrate (1-phenylethyl butanoate) was performed (13; see also the supplemental methods). The conversion of reaction and the enantiomeric excess of the product (R)-phenylethanol obtained at 5 h were both improved by GadBC coexpression—over 30 and 12% of conversion, and 99 and 94% of enantiomeric excess with and without GadBC coexpression, respectively. This result suggests that the lipase-displaying cells coexpressing the gadBC genes have an advantage of enhanced functional expression of lipase on the cell surface. This enhanced lipase display is expected to be widely useful for the production of enantiomerically pure compounds as an effective biocatalytic system in the fields of fine chemicals, pharmaceuticals, agrochemicals, and other demanding industries.

There has so far been no report on the roles of GadBC in cell surface display systems. However, it has been reported that GadBC proteins are involved in stress responses such as acid shock, anaerobic phosphate starvation, salt stress, and stationary-phase stress (7, 16). Thus, cell surface display of lipase (and possibly other proteins as well) seems to act like a stress to the cell due to the greater than normal amount of protein export, translocation, and anchoring onto the cell envelope. Even though the exact mechanism needs to be elucidated, the results of this study suggest that coexpression of the gadBC genes, identified by transcriptome profiling, improves lipase display on E. coli cell surfaces. This is an additional example of employing transcriptome profiling for the identification of gene manipulation targets for improving the performance of microorganisms.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Korean Systems Biology Research Grant from the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (MEST) through the Korean Science and Engineering Foundation (M10309020000-03B5002-00000). Further support by the LG Chem Chair Professorship and the World Class University Program of MEST is appreciated.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 30 November 2009.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baek, J. H., and S. Y. Lee. 2006. Novel gene members in the Pho regulon of Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 265:104-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen, W., and G. Georgiou. 2002. Cell-surface display of heterologous proteins: from high-throughput screening to environmental applications. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 79:496-503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Choi, J. H., J.-I. Choi, and S. Y. Lee. 2005. Display of proteins on the surface of Escherichia coli by C-terminal deletion fusion to the Salmonella typhimurium OmpC. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 15:141-146. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choi, J. H., S. J. Lee, S. J. Lee, and S. Y. Lee. 2003. Enhanced production of insulin-like growth factor I fusion protein in Escherichia coli by coexpression of the down-regulated genes identified by transcriptome profiling. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:4737-4742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Darwin, A. J. 2005. The phage-shock-protein response. Mol. Microbiol. 57:621-628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Datsenko, K. A., and B. L. Wanner. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:6640-6645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Biase, D., A. Tramonti, F. Bossa, and P. Visca. 1999. The response to stationary-phase stress conditions in Escherichia coli: role and regulation of the glutamic acid decarboxylase system. Mol. Microbiol. 32:1198-1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeLisa, M. P., P. Lee, T. Palmer, and G. Georgiou. 2004. Phage shock protein PspA of Escherichia coli relieves saturation of protein export via the Tat pathway. J. Bacteriol. 186:366-373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Georgiou, G., C. Stathopoulos, P. S. Daugherty, A. R. Nayak, B. L. Iverson, and R. Curtiss III. 1997. Display of heterologous proteins on the surface of microorganisms: from the screening of combinatorial libraries to live recombinant vaccines. Nat. Biotechnol. 15:29-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Han, M.-J., K. J. Jeong, J. S. Yoo, and S. Y. Lee. 2003. Engineering Escherichia coli for increased productivity of serine-rich proteins based on proteome profiling. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:5772-5781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jeanteur, D., J. H. Lakey, and F. Pattus. 1991. The bacterial porin superfamily: sequence alignment and structure prediction. Mol. Microbiol. 5:2153-2164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee, S. H., J. Choi, M.-J. Han, J. H. Choi, and S. Y. Lee. 2005. Display of lipase on the cell surface of Escherichia coli using OprF as an anchor and its application to enantioselective resolution in organic solvent. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 90:223-230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee, S. H., J.-I. Choi, S. J. Park, S. Y. Lee, and B. C. Park. 2004. Display of bacterial lipase on the Escherichia coli cell surface by using FadL as an anchoring motif and use of the enzyme in enantioselective biocatalysis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:5074-5080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee, S. H., S. Y. Lee, and B. C. Park. 2005. Cell surface display of lipase in Pseudomonas putida KT2442 using OprF as an anchoring motif and its biocatalytic applications. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:8581-8586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee, S. Y., J. H. Choi, and Z. Xu. 2003. Microbial cell-surface display. Trends Biotechnol. 12:45-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moreau, P. L. 2007. The lysine decarboxylase CadA protects Escherichia coli starved of phosphate against fermentation acids. J. Bacteriol. 189:2249-2261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Park, S. J., and S. Y. Lee. 2003. Identification and characterization of a new enoyl coenzyme A hydratase involved in biosynthesis of medium-chain-length polyhydroxyalkanoates in recombinant Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 185:5391-5397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park, J. H., K. H. Lee, T. Y. Kim, and S. Y. Lee. 2007. Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli for the production of l-valine based on transcriptome analysis and in silico gene knockout simulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:7797-7802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park, J. H., S. Y. Lee, T. Y. Kim, and H. U. Kim. 2008. Application of systems biology for bioprocess development. Trends Biotechnol. 26:404-412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Richard, H., and J. W. Foster. 2004. Escherichia coli glutamate- and arginine-dependent resistance systems increase internal pH and reverse transmembrane potential. J. Bacteriol. 186:6032-6041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wittrup, K. D. 2001. Protein engineering by cell-surface display. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 12:395-399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu, C. H., A. Mulchandani, and W. Chen. 2008. Versatile microbial surface-display for environmental remediation and biofuels production. Trends Microbiol. 16:181-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu, Z., and S. Y. Lee. 1999. Display of polyhistidine peptides on the Escherichia coli cell surface by using outer membrane protein C as an anchoring motif. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:5142-5147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.