Abstract

Current dietary therapy for long-chain 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase (LCHAD) or trifunctional protein (TFP) deficiency consists of fasting avoidance, and limiting long-chain fatty acid (LCFA) intake. This study reports the relationship of dietary intake and metabolic control as measured by plasma acylcarnitine and organic acid profiles in 10 children with LCHAD or TFP deficiency followed for 1 year. Subjects consumed an average of 11% of caloric intake as dietary LCFA, 11% as MCT, 12% as protein, and 66% as carbohydrate. Plasma levels of hydroxypalmitoleic acid, hydroxyoleic, and hydroxylinoleic carnitine esters positively correlated with total LCFA intake and negatively correlated with MCT intake suggesting that as dietary intake of LCFA decreases and MCT intake increases, there is a corresponding decrease in plasma hydroxyacylcarnitines. There was no correlation between plasma acylcarnitines and level of carnitine supplementation. Dietary intake of fat-soluble vitamins E and K was deficient. Dietary intake and plasma levels of essential fatty acids, linoleic and linolenic acid, were deficient. On this dietary regimen, the majority of subjects were healthy with no episodes of metabolic decompensation. Our data suggest that an LCHAD or TFP-deficient patient should adhere to a diet providing age-appropriate protein and limited LCFA intake (10% of total energy) while providing 10–20% of energy as MCT and a daily multi-vitamin and mineral (MVM) supplement that includes all of the fat-soluble vitamins. The diet should be supplemented with vegetable oils as part of the 10% total LCFA intake to provide essential fatty acids.

Keywords: Long-chain 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency, Trifunctional protein deficiency, Long-chain fatty acids, Medium-chain triglycerides, Acylcarnitines, Essential fatty acids

Introduction

Inherited deficiency of long-chain 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase [LCHAD; EC 1.1.1.211] or tri-functional protein (TFP) severely impairs mitochondrial long-chain fatty acid (LCFA) β-oxidation and typically manifests with acute episodes of fasting or illness-induced hypoketotic hypoglycemia. Cardiomyopathy, severe liver disease, and recurrent muscle cramps with rhabdomyolysis can occur during acute illness. Patients with LCHAD or TFP deficiency may also develop long-term complications such as peripheral neuropathy or pigmentary retinopathy leading to impaired vision. Accumulation of plasma long-chain 3-hydroxyacylcarnitines and fatty acids, and dicarboxylic acids in urine are the biochemical hallmarks of this disorder [1,2].

Currently, clinical and dietary management of LCHAD and TFP deficiency are based upon avoidance of fasting and medium-chain triglyceride (MCT) supplementation to prevent hypoglycemia and acute metabolic decompensation [3]. Reduction in dietary long-chain fatty acid (LCFA) intake along with MCT supplementation likely suppress long-chain fatty acid β-oxidation and prevent the accumulation of potentially toxic long-chain 3-hydroxy fatty acids and/or acylcarnitines. We previously evaluated the effects of dietary manipulations on plasma and urine laboratory values in one child with LCHAD deficiency [4]. The goal of this study was to evaluate the effects of contemporary dietary therapy upon various biochemical parameters of metabolic control and clinical outcome in 10 other children with either LCHAD or TFP deficiency.

Methods

Ten children with known LCHAD or TFP deficiency were evaluated on two separate occasions over a 12-month period. The study protocol was approved by the Human Subjects Institutional Review Board of Oregon Health and Science University (OHSU) and each subject’s legal guardian gave written informed consent. Subjects were admitted to the General Clinical Research Center (GCRC) at OHSU for physical evaluation and review of past medical history. A research nurse obtained the subject’s height, weight, and a blood sample for analysis of essential fatty acids, plasma acylcarnitines, and organic acids. Blood samples were taken following a four-hour fast in 7 subjects prior to sedation for unrelated tests. The length of time from the last meal was unknown in three-older subjects who did not require sedation for testing. The patients’ dietary regimen as prescribed by their referring physicians was not altered initially but rather nuances in treatment were compared with biochemical parameters and outcome.

Mutational analysis

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of the exons of the gene encoding both α- and β-subunits was performed on genomic DNA isolated from cultured skin fibroblasts or peripheral-blood leukocytes in the laboratory of Dr. Arnold Strauss (Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN) [5]. The presence of the common G1528C mutation was examined by restriction fragment polymorphism analysis as previously described [6]. Single-strand conformation polymorphisms analysis was used to screen for mutations in any allele not carrying the common mutation. Polymorphisms were confirmed by direct DNA sequencing.

Dietary intake

A parent of each subject completed a three-day diet record during each evaluation. A nutritionist reviewed diet records with the subject and parent for completeness and accuracy. Records were analyzed using ESHA Food Processor Nutrition and Fitness Software version 7.71 (ESHA Research, Salem, OR). Average daily intake of energy nutrients (carbohydrate, protein, LCFA, and MCT), vitamins and minerals, and individual fatty acids were used for statistical analysis.

Subjects

Seven females and three males ranging in age from 1 to 10 years were evaluated. General characteristics of all subjects are given in Table 1. Four children were homozygous for c.1528G> C, four were compound heterozygous for c.1528G>C along with private mutations in the trifunctional protein α-subunit, and two sisters were compound heterozygous for a unique β-subunit mutation and one unknown mutation resulting in TFP deficiency. Mutations were not identified within the α-subunit coding region in three of the 20 alleles. All subjects were following a diet restricted in LCFA and were in good health at the time of evaluation. Nine subjects were supplemented with MCT contributing from 1 to 24% of the subject’s average daily energy intake. Nine subjects were supplemented with carnitine; one subject was not taking carnitine at the initial evaluation but had begun carnitine supplementation by the second evaluation. One subject has never received carnitine. The carnitine dose in the nine patients receiving it varied from 10 to 153 mg carnitine/kg body weight/day (mean: 77 mg/kg/d). Eight subjects were taking a daily multi-vitamin and mineral (MVM) supplement. Three subjects were consuming commercial infant formulas as part of their daily diets and six subjects were prescribed supplemental vegetable oil such as canola, walnut, or linseed oil to provide essential fatty acids.

Table 1.

Characteristics of subjects

| Subject | Age (years) |

Gender | Mutations | Age at initial presentation |

Medications and supplements | Residual enzyme activity (nmol/min/mg of protein) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carnitine (mg/kg/d) |

MCT intake (% caloric intake) |

Other supplements | LCHAD | Ketothiolase | |||||

| 1# | 10 | F | c.901G>A β-subunit/? |

3 years | 88 | 15 | MVM; calcium | 12.4 | 0.4 |

| 2 | 7 | M | c.1528G>C/ c.1528G>C |

3 months | 69 | 11 | MVM; vegetable oil | 11.8 | 38.6 |

| 3# | 5 | F | c.901G>A β-subunit/? |

2 year | 90 | 21 | MVM; calcium | NA | NA |

| 4 | 3 | F | c.1528G>C/ c.274_278del |

1 day | 10 | 8 | MVM; walnut oil | 10.2 | 10.7 |

| 5 | 1 | F | c.1528G>C/ c.1528G>C |

3 days | 0 | 18 | Portagen, walnut oil | NA | NA |

| 6 [7] | 8 | F | c.1528G>C/ c.1528G>C |

4 months | 26 | 0 | none | 10.7 | 21.0 |

| 7 | 5 | F | c.1528G>C/ c.274_278del |

9 months | 85 | 8 | MVM, walnut oil | 0.4 | NA |

| 8f | 3 | F | c.1528G>C/ c.1528G>C |

Dx d/t sibling | 91 | 3 | Alimentum MVM; walnut oil | NA | NA |

| 9f | 4 | M | c.1528G>C/ c.1528G>C |

4 months | 93 | 8 | Portagen, MVM; walnut oil | NA | NA |

| 10 | 10 | M | c.1528G>C/? | 6 months | 136 | 14 | MVM | NA | NA |

Mutations are in the α-subunit of the trifunctional protein unless otherwise noted.

“?” indicates alleles in which no mutations were identified following the sequencing of exons in both the α- and β-subunits. Patients have one known mutation and clinical and biochemical evidence of LCHAD/TFP deficiency.

“#/f”symbols indicate siblings MVM, multi-vitamin and mineral supplement; Portagen, infant formula made by Mead Johnson; Alimentum, infant formula made by Ross.

Plasma essential fatty acids

Plasma samples from five subjects were analyzed twice using a GC/MS method (results expressed as µmol/L) [8] and a procedure by gas chromatography (GC) with a flame ionization detector where results are expressed as a percent of total fatty acids [9]. Plasma samples from four subjects were analyzed by the second method only in the Peroxisomal Diseases laboratory at the Kennedy Krieger Institute (Baltimore, MD) [10]. Results were expressed as both micromoles per liter concentration and as a percent of total fatty acids. The plasma essential fatty acids from one subject were not included because the sample was not a fasting sample.

Plasma acylcarnitine profile

Plasma acylcarnitines were measured by electrospray tandem mass spectrometry (ESI-MS/MS; Perkin–Elmer Sciex API 2000) as previously described [11].

Plasma 3-hydroxy fatty acid analysis

3-Hydroxy-C17-carboxylic and 3-hydroxy-C18-carboxylic acids were purchased from Matreya (Pleasant Gap, PA). Plasma samples were prepared and analyzed for 3-hydroxy-C18-carboxylic acid levels as follows: 70 µl water, 10 µl of 6N HCl, 30µl plasma, and 2ml ethyl acetate were added to 0.1 µg of 3-hydroxy-C17-carboxylic acid internal standard in a 13 × 100 mm screw cap tube. Dilutions of the 3-hydroxy-C18-carboxylic acid were prepared similarly to establish a standard curve. The mixture was shaken vigorously, centrifuged, the upper layer was removed to a new tube and samples were dried under nitrogen. Samples were then derivatized with 30 µl BSTFA-1% TMCS (Pierce) at 85 °C for 20 min. Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry was performed by splitless injection into a Hewlett-Packard 6890 gas chromatograph equipped with a 25 m × 0.2 mm i.d. HP-1 column; film thickness 0.33 µm. The Hewlett-Packard 5973 mass selective detector was operated in selected ion monitoring mode and programmed to detect specific ions from both the internal standard (ions 233 and 415) and the 3-hydroxy-C18-carboxylic acid standard (ions 233 and 429). Samples were quantified using a multi-point calibration of the analyte standards (ion 429) referenced to the internal standard (ion 415). The only possible interference noted was 2 peak widths away from the analyte signal and was smaller than the analyte signal in normal controls. Patient samples were compared to adult normal values (n = 10).

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as means ± standard deviation (SD) for 20 observations, 2 measurements in each of 10 subjects, unless otherwise stated. Plasma levels of acylcarnitines, free fatty acids, and 3-hydroxy fatty acids were correlated with dietary intake of LCFA, individual fatty acids, MCT, and carnitine supplementation using SAS, Windows v.8 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). A two-tailed Student’s t test was used to compare plasma acylcarnitine levels of subjects consuming less than 10% energy from MCT (n = 10 time points) with those consuming more than 10% of energy from MCT (n = 10 time points). P ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Energy nutrient intake

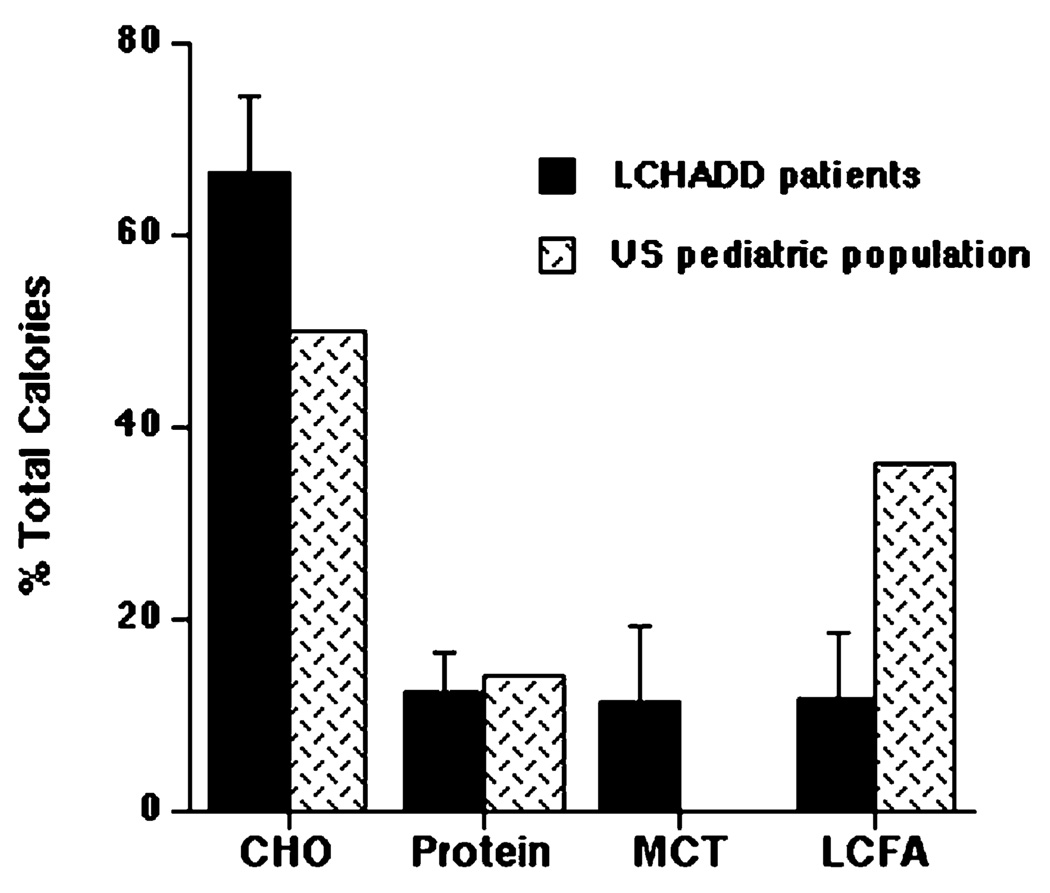

Subjects consumed an average of 11% of caloric intake as dietary LCFA (range = 4 to 30%), 11% as MCT, 12% as protein and 66% as carbohydrate (Fig. 1). Dietary intake of LCFA was much lower and carbohydrate and MCT intake higher than the general US pediatric population [12,13]. Protein intake of children with LCHAD deficiency was similar to the general US pediatric population with a mean intake of 2.5 g/kg body weight/day and a range 1.3–5 g/kg/d.

Fig. 1.

Dietary intake of carbohydrate (CHO), protein, medium-chain triglyceride (MCT), and long-chain fatty acids (LCFA) in 10 children with LCHAD deficiency (black bars) compared to the published estimated intake of the US pediatric population (hatched bars) [12]. Data are presented as mean intake ± standard deviation (SD).

Vitamin and mineral intake

Subjects’ vitamin and mineral intake from foods and formula but not from MVM supplements are summarized in Table 2. Intake of retinol equivalents (preformed vitamin A and β-carotene) from food was equal to or above the recommended dietary intake (RDI) for all but one subject. Additional vitamin A was provided in a MVM supplement for that subject and seven others. Thus, vitamin A intake was sufficient. Dietary intake of the other fat-soluble vitamins D, E, and K was slightly below recommended levels but additional amounts of these vitamins were provided in a daily MVM supplement for eight of the 10 subjects. Intake of water-soluble vitamins and minerals from food was equal to or greater than the RDI.

Table 2.

Vitamin and mineral intake of 10 children with LCHAD deficiency

| Range | Mean ± SD | RDA/AI | UL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin | ||||

| Vitamin A (RE µg) | 192–1777 | 898 ± 540 | 400 | 900 |

| Vitamin D (µg) | 1.2–12 | 4.7 ± 3.8 | 5 | 50 |

| Vitamin E (mg) | 1–15 | 5.7 ± 4.9 | 7 | 300 |

| Vitamin K (µg) | 4–73 | 29 ± 21.5 | 55 | ND |

| Thiamin (mg) | 0.48–1.9 | 1.2 ± 0.55 | 0.6 | ND |

| Riboflavin (mg) | 0.72–3.29 | 1.6 ± 0.79 | 0.6 | ND |

| Niacin (mg) | 4.4–36.9 | 16.3 ± 9.3 | 8 | 15 |

| Vitamin B6 (mg) | 0.4–3.3 | 1.3 ± 0.72 | 0.6 | 40 |

| Vitamin B12 (mg) | 0.6–6.1 | 2.6 ± 1.5 | 1.2 | ND |

| Folate (µg) | 52–649 | 230 ± 138 | 200 | 400 |

| Vitamin C (mg) | 27–223 | 102 ± 54 | 25 | 650 |

| Mineral | ||||

| Calcium (mg) | 306–1630 | 895 ± 396 | 800 | 2500 |

| Iron (mg) | 6.5–16.1 | 11.9 ± 3.7 | 10 | 40 |

| Magnesium (mg) | 62–277 | 160 ± 65 | 130 | 110a |

| Phosphorous (mg) | 224–1572 | 846 ± 378 | 500 | 3000 |

| Zinc (mg) | 1.8–8.8 | 5.5 ± 2.2 | 5 | 12 |

Vitamin and mineral intake from food and formula but not from daily vitamin and mineral supplements are presented as the range (lowest to highest intake, column 2) and mean ± standard deviation (SD, column 3). The recommended daily allowance (RDA) in bold type or adequate intakes (AI) in ordinary type for children 4–8 years of age is given in column 4. The upper limit (UL) of recommended intake is given in column 5. ND, not determinable due to a lack of data on adverse effects.

The UL for magnesium represents intake from a pharmacological agent only and does not include intake from food and water.

Plasma fatty acids

Levels of selected plasma essential fatty acids measured at the initial evaluation (n = 9) are given in Table 3. A fasting blood sample was not available for one subject. When expressed as a concentration, plasma levels of linoleic acid (C18:2n − 6), the parent ω-6 fatty acid, were deficient in all nine subjects, and arachidonic acid was deficient in four subjects but when expressed as a percent of total, only two subjects were deficient in linoleic acid and no subjects were deficient in arachidonic acid. Mean plasma concentrations but not relative percentage of linoleic and arachidonic acid are deficient. This suggests there is an absolute ω-6 fatty acid deficiency but that the relationship between ω-6 fatty acids and other fats is maintained. When expressed as a concentration, plasma levels of linolenic acid (C18:3n − 3), the parent ω-3 fatty acid, were deficient in seven subjects, eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA; C20:5n − 3) was deficient in three subjects, and DHA was deficient in two subjects. However, the relative percentage of linolenic acid was low in only two subjects, EPA was low in one subject, and DHA was normal for all subjects. Plasma concentrations of ω-3 fatty acids appear to be deficient but the relative percentage of ω-3 fatty acids compared to other fatty acids is maintained.

Table 3.

Plasma essential fatty acids in nine children with LCHAD deficiency

| µmol/L | Relative peak % | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal range |

Mean | SD | # deficient | Normal range |

Mean | SD | # deficient | ||

| ω-6 fatty acids | |||||||||

| C18:2ω-6 | Linoleic | 2270–3850 | 1594 | 330 | 9 | 22.89–36.45 | 26.03 | 4.94 | 2 |

| C20:4ω-6 | Arachidonic | 520–1490 | 476 | 166 | 4 | 4.79–10.99 | 8.13 | 2.6 | 0 |

| ω-3 fatty acids | |||||||||

| C18:3ω-3 | α-Linolenic | 50–130 | 36 | 21 | 7 | 0.26–0.94 | 0.6 | 0.45 | 2 |

| C20:5ω-3 | EPA | 14–100 | 24 | 11 | 3 | 0.15–0.99 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 1 |

| C22:6ω-3 | DHA | 30–250 | 54 | 27 | 2 | 0.37–2.29 | 1.26 | 0.62 | 0 |

SD, standard deviation; EPA, eicosapentaenoic acid; DHA, docosahexaenoic acid.

# deficient indicates number of subjects with fatty acid levels below the normal range.

Children with LCHAD or TFP deficiency following very low fat diets have low total plasma fatty acids but the relative percentage of each fatty acid species appears to be normal. Abundant saturated and monounsaturated plasma fatty acids are presented in Table 4 to further illustrate this result. Plasma concentrations of palmitate and stearate, the two most common saturated fatty acids in food, are below the normal range in 4 and 6 subjects, respectively. Plasma concentrations of palmitoleic and oleic acids are below normal in one subject. The relative percentage of these fatty acids is normal or elevated.

Table 4.

Main plasma fatty acids in nine children with LCHAD deficiency

| µmol/L | Relative peak % | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal range |

Mean | SD | # deficient | Normal range |

Mean | SD | # elevated | ||

| C16:0 | Palmitic | 1480–3730 | 1553 | 359 | 4 | 14.1–24.5 | 20.84 | 2.26 | 1 |

| C18:0 | Stearic | 590–1170 | 573 | 143 | 6 | 5.9–8.9 | 7.9 | 0.91 | 1 |

| C16:1 | Palmitoleic | 110–1130 | 306 | 188 | 1 | 0.45–3.01 | 3.46 | 0.93 | 7 |

| C18:1 | Oleic | 650–3500 | 1188 | 417 | 1 | 11.95–21.35 | 19.26 | 4.01 | 2 |

SD, standard deviation.

# deficient indicates number of subjects with fatty acid levels below the normal range.

# elevated indicates number of subjects with fatty acid peak (%) above the normal range.

Plasma acylcarnitines

Plasma levels of 3-hydroxyhexadecenoylcarnitine (C16:1-OH), 3-hydroxyoleylcarnitine (C18:1-OH), and 3-hydroxylinoleylcarnitine (C18:2-OH) (data not shown) correlated positively with total LCFA intake (Fig. 2). This suggests that as dietary intake of LCFA increases there is a corresponding increase in plasma hydroxyacylcarnitines. Palmitoleic (C16:1), oleic (C18:1), and linoleic (C18:2) acids are abundant in the American diet and a positive correlation was also observed when the amounts of these fatty acids consumed per day were plotted against plasma levels of the corresponding hydroxyacylcarnitine. In contrast, plasma levels of hydroxypalmitoylcarnitine (C16: 0-OH, data not shown), C16:1-OH, C18:1-OH, and C18: 2-OH species (data not shown) negatively correlated with MCT intake (Fig. 3) suggesting that, as MCT intake increases, there is a corresponding decrease in plasma hydroxyacylcarnitines, a response that has been noted previously [2,14]. There was no relationship between plasma hydroxyacylcarnitine levels and the amount of carnitine supplementation in these patients (Fig. 4). Thus, it seems, carnitine supplementation does not affect the plasma concentrations of these metabolites.

Fig. 2.

Percent of caloric intake as LCFA (x-axis) correlated with plasma levels of 3-hydroxypalmitoleic (C16:1-OH) and 3-hydroxyoleic (C18:1-OH) acylcarnitines (y-axis) in 10 children with LCHAD deficiency. The normal range is indicated by the gray shaded area. R2, correlation coefficient; p, significance (p value).

Fig. 3.

Percent of caloric intake as MCT (x-axis) negatively correlated with plasma levels of 3-hydroxypalmitoleic (C16:1-OH) and 3-hyroxyoleic (C18:1-OH) acylcarnitines (y-axis) in 10 children with LCHAD or TFP deficiency. The normal range is indicated by the gray shaded area. R2, correlation coefficient; p, significance (p value).

Fig. 4.

Supplemental carnitine intake (mg/kg body weight) (x-axis) correlated with plasma levels of 3-hydroxypalmitoleic (C16:1-OH) and 3-hyroxyoleic (C18:1-OH) acylcarnitines (y-axis) in 10 children with LCHAD deficiency. The normal range is indicated by the gray shaded area. R2, correlation coefficient; p, significance (p value).

Plasma 3-hydroxy-C18:0 fatty acid

Four plasma samples were not available for analysis. Data represent the correlation of metabolite levels with the dietary intake of LCFA, MCT, and carnitine supplementation. The normal range was 0.14–0.26 with a mean of 0.2 ± 0.03 µmol/L in plasma from 10 healthy adults. The intraassay coefficient of variation for 10 selected patient samples was 3% but the largest single variation (15%) was noted in a sample containing about 0.5 µmol/L. Plasma levels of C18:0 hydroxyacylcarnitines highly correlated with plasma levels of 3OH-C18:0 (P = 0:009). There was a trend for plasma levels of 3OH-C18:0 to positively correlate to LCFA intake, negatively correlate to MCT intake and have no relationship to level of carnitine supplementation, as was demonstrated for plasma acylcarnitines (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Percent of caloric intake as LCFA (x-axis), percent of caloric intake as MCT, and supplemental carnitine (mg/kg body weight) correlated with plasma levels of 3-hydroxystearate (C18:0-OH) (y-axis) in 10 children with LCHAD deficiency (n = 16 timepoints). R2, correlation coefficient; p, significance (p value).

Clinical outcome

Over the course of one year, following the dietary regimen described above, all subjects maintained their predicted growth pattern (males between 10–75% tile weight for age and 50–95% tile height for age; females 5–95% tile weight for age and 5–90% tile height for age). Six of 10 subjects were healthy with no episodes of metabolic decompensation and no hospitalizations. One subject was hospitalized for pneumonia and treated with IV fluids, dextrose, and antibiotics. Two subjects were hospitalized for emesis and dehydration associated with a concurrent viral infection and were treated with IV fluids and dextrose. One subject was hospitalized twice during the year with episodes of rhabdomyolysis (maximum CPK = 30,000 U/L) associated with physical activity (baseball). He was treated with rest, IV fluids and dextrose. There was no evidence of decreased growth, cardiomyopathy or hepatic dysfunction in this group of subjects. None of the subjects were hypoglycemic during an episode before they were treated with IV fluids and dextrose.

Discussion

Possible pathophysiological mechanisms that result in acute and chronic symptoms of LCHAD deficiency include: (1) energy deficit with fasting, (2) toxicity of accumulating long-chain fatty acids, (3) toxicity of accumulating long-chain hydroxyacylcarnitines, or (4) deficiency of essential compounds such as ω-6 and ω-3 fatty acids. Rational therapy for LCHAD deficiency should be directed toward correcting or preventing these mechanisms. Contemporary dietary therapy has consisted of fasting avoidance, limitation of dietary LCFA intake to minimize excess long-chain fatty acid or hydroxyacylcarnitine accumulation, and supplementation with MCT oil and/or carnitine. While this approach is generally consistent among genetic centers in the United States, the frequency of feeding, dietary fat restriction, and type and amount of other supplements varies (from center to center). The goal of this report was to evaluate 10 children with LCHAD or TFP deficiency to determine the optimal dietary therapy with the aim of addressing these potential pathophysiological mechanisms.

Dietary LCFA intake positively correlated to both plasma long-chain hydroxyacylcarnitine and fatty acid levels. Thus, as dietary long-chain fat intake increased, blood levels of LCHAD-related metabolites increased as well. We previously reported this relationship in a single child [4], but we have now observed this same relationship in a larger group of children with various defects in the trifunctional protein complex. Intake of approximately 10% of caloric intake as LCFA was associated with near normal plasma long-chain hydroxyacylcarnitine profiles.

Further restriction of dietary LCFA intake to less than 10% of caloric intake is associated with a very high risk of essential fatty acid deficiency [15]. Signs of essential fatty acid deficiency include dry scaly skin, dermatitis, hair loss, and in children, decreased growth [15,16]. We have not observed these symptoms in this patient population but we have previously reported low plasma DHA levels in four patients with LCHAD deficiency [17]. Plasma fatty acid data from nine subjects described in this report suggest that children with LCHAD deficiency treated with low-fat diets have low-total plasma fatty acids and both ω-6 and ω-3 fatty acid deficiencies. The methods used to diagnose essential fatty acid deficiency are critical. Results from fatty acid analysis should be calculated as a concentration in the sample and compared to normal controls. The relative percentage, but not the absolute amount of fatty acids, appears to be maintained even during severe dietary fat restriction. Low plasma DHA levels are most likely due to low dietary intake of total ω-3 fatty acids, although a defect in the synthesis of DHA from linolenic acid has not been ruled out.

Patients, especially children, on very low-fat diets are at high risk for fat-soluble vitamin deficiencies as well. Dietary intake of vitamin A and β-carotene from foods was adequate in nine of the 10 subjects. In the one subject with poor intake of retinol from food, additional vitamin A was prescribed in the form of a daily MVM supplement. Plasma markers of vitamin A status have not been measured in these subjects but it appears that dietary intake of retinol equivalents is adequate. The primary source of vitamin A (and vitamin D) in foods was non-fat milk. Dietary intake of foods high in vitamins K and E, such as dark green leafy vegetables and nuts, was negligible. Thus, intake of vitamins K and E were lower than recommended levels. Dietary intakes of water-soluble vitamins and minerals from foods were within recommended levels. A daily MVM supplement provides additional fat-soluble vitamins and other micronutrients for patients on very low-fat diets.

MCT supplementation is routinely utilized in the treatment of LCHAD deficiency and several in vitro and in vivo studies have indicated a potential benefit [2,14]. Duran et al. [18] reported decreased plasma lactate and long-chain acylcarnitines with the initiation of MCT supplementation in an infant with LCHAD deficiency and we noted lower venous lactate levels with increased levels of MCT supplementation in one child with LCHAD deficiency [4]. LCHAD-deficient fibroblasts incubated with palmitate supplemented media had characteristic increases in long-chain hydroxyacylcarnitines in both cells and media, but when cells were incubated with either C8:0 or C10:0 containing media, acylcarnitine profiles were similar to normal controls [14]. In addition, a retrospective analysis of plasma acylcarnitines in three LCHAD-deficient patients demonstrated a 29–93% reduction in hydroxy-C16:0 and C18:1 acylcarnitines following the initiation of MCT supplementation [2]. The negative correlation between MCT intake and plasma hydroxyacylcarnitine profiles found in our study suggests that MCT supplementation suppresses long-chain fatty acid oxidation and prevents accumulation of abnormal metabolites. Subjects consuming 10% or greater of total energy as MCT had significantly lower plasma 3-hydroxacylcarnitine levels than subjects consuming less then 10% of energy as MCT (P < 0.04).

Previous in vitro and in vivo studies in children with LCHAD deficiency have found characteristic increases in C16:0-OH, C14:1-OH, and C14:0-OH acylcarnitines. Although these acylcarnitine species were mildly to moderately elevated in our samples, we did not detect a significant correlation between plasma C16:0-OH, C14:1-OH, and C14:0-OH acylcarnitines and dietary LCFA intake. There was, however, a significant negative correlation between MCT intake and plasma levels of hydroxy palmitoylcarnitine (C16:0-OH). The difference in profiles observed in this report and those previously published is most likely related to the replacement of dietary palmitate with MCT and/or the suppression of C16:0 acylcarnitine production by MCT. There is a significant negative correlation between dietary palmitate and MCT intake, suggesting that supplemental MCT replaced dietary palmitate in the diets of these subjects. The one subject who was not supplemented with MCT consumed an average of 2.3% of total energy from palmitate per day and the other nine subjects consumed an average of 0.8% of total energy from palmitate per day.

Supplementation with heptanoate (C7) triglyceride has recently been investigated as a potentially beneficial therapy in three children with very long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency [19], and the authors suggest that C7 supplementation would also be useful for LCHAD deficiency. However, the advantage of supplementing with equimolar amounts of C7 over traditional MCT oil (predominantly C8) in children with LCHAD deficiency has not been established. Results from this study and others strongly suggest that MCT supplementation suppresses long-chain fatty acid oxidation and decreases the production of potentially toxic hydroxyacylcarnitine species and organic acids [2,4,18].

The use of l-carnitine supplementation in LCHAD and TFP deficiency is controversial, with little data supporting either beneficial or harmful effects. In this study, there was wide variation in the dose of carnitine prescribed to subjects ranging from 10 to 153 mg/kg body weight. No untoward effects of carnitine supplementation were documented in this patient population. If supplemental carnitine had improved urinary excretion of long-chain 3-hydroxycarnitine esters, one might expect a negative correlation between levels of carnitine supplementation and plasma levels of hydroxyacylcarnitines. However, in this trial, no correlation between carnitine supplementation and plasma hydroxyacylcarnitine or plasma organic acid levels was observed. We did not attempt to measure timed urinary excretion of dicarboxylic acids. A recent report describing 50 patients with LCHAD deficiency also found no correlation between carnitine supplementation and frequency of metabolic decompensation [20]. These data suggest that dietary intake of LCFA and MCT but not carnitine are related to metabolic control and improved biochemical parameters.

In conclusion, we report the effects of dietary therapy in 10 subjects with either LCHAD or TFP deficiency. All patients had been directed by their treating physicians to avoid fasting and receive adequate energy to limit fatty acid oxidation, but a more specific dietary regimen had not been prescribed. Our data suggest that an LCHAD or TFP-deficient patient should adhere to a diet providing age-appropriate protein and limited LCFA intake (10% of caloric intake per day) while providing 10–20% of caloric intake as MCT. Furthermore, a daily MVM supplement that includes all of the fat-soluble vitamins will ensure adequate amounts of micronutrients. Because of the LCFA restriction, patients are at risk for essential fatty acid deficiency. The diet should therefore be supplemented with vegetable oils as part of the 10% total LCFA intake to provide essential fatty acids. The National Institute of Medicine recommends children between 4 and 8 years of age consume 10 g linoleic acid and 0.9 g α-linolenic acid per day [21]. Following this dietary protocol, six subjects were healthy and did not experience episodes of serious metabolic decompensation over the course of one year. Four subjects were briefly hospitalized for concurrent infections or rhabdomyolysis and treated with IV fluids and dextrose. No evidence of hypoglycemia, cardiomyopathy, hepatic dysfunction or decreased growth was measured. However, long-term complications of LCHAD deficiency including pigmentary retinopathy or peripheral neuropathy may not be absolutely prevented by this dietary regimen [22]. Longer-term studies will be required to assess the evolution of LCHAD deficiency-associated complications during optimal dietary therapy.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by PHS Grant 5 M01 RR00334. We thank Ann Moser, director of the Kennedy Krieger Peroxisomal Lab(Baltim ore, MD), for analyzing some of our plasma fatty acid samples and Dr. Arnold Strauss (Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN) for sequencing the trifunctional protein genes for this project.

References

- 1.Costa CG, Dorland L, Holwerda U, de Almeida IT, Poll-The BT, Jakobs C, Duran M. Simultaneous analysis of plasma free fatty acids and their 3-hydroxy analogs in fatty acid β-oxidation disorders. Clin. Chem. 1998;44:463–471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van Hove JL, Kahler SG, Feezor MD, Ramakrishna JP, Hart P, Treem WR, Shen JJ, Matern D, Millington DS. Acylcarnitines in plasma and blood spots of patients with long-chain 3-hydroxyacyl-coenzyme A dehydrogenase deficiency. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2000;23:571–582. doi: 10.1023/a:1005673828469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saudubray JM, Martin D, de Lonlay P, Touati G, Poggi-Travert F, Bonnet D, Jouvet P, Boutron M, Slama A, Vianey-Saban C, Bonnefont JP, Rabier D, Kamoun P, Brivet M. Recognition and management of fatty acid oxidation defects: a series of 107 patients. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 1999;22:488–502. doi: 10.1023/a:1005556207210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gillingham M, Van Calcar SC, Ney DM, Wolff J, Harding CO. Dietary management of long-chain 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency (LCHADD). A case report and survey. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 1999;22:123–131. doi: 10.1023/a:1005437616934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ibdah JA, Bennett MJ, Rinaldo P, Zhao Y, Gibson B, Sims HF, Strauss AW. A fetal fatty-acid oxidation disorder as a cause of liver disease in pregnant women. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999;340:1723–1731. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199906033402204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sims HF, Brackett JC, Powell CK, Treem WR, Hale DE, Bennett MJ, Gibson B, Shapiro S, Strauss AW. The molecular basis of pediatric long chain 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency associated with maternal acute fatty liver of pregnancy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:841–845. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.3.841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Treem WR, Rinaldo P, Hale DE, Stanley CA, Millington DS, Hyams JS, Jackson S, Turnbull DM. Acute fatty liver of pregnancy and long-chain 3-hydroxyacyl-coenzyme A dehydrogenase deficiency. Hepatology. 1994;19:339–345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lagerstedt SA, Hinrichs DR, Batt SM, Magera MJ, Rinaldo P, McConnell JP. Quantitative determination of plasma c8–c26 total fatty acids for the biochemical diagnosis of nutritional and metabolic disorders. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2001;73:38–45. doi: 10.1006/mgme.2001.3170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harris WS, Connor WE, Lindsey S. Will dietary ω-3 fatty acids change the composition of human milk? Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1984;40:780–785. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/40.4.780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moser AB, Jones DS, Raymond GV, Moser HW. Plasma and red blood cell fatty acids in peroxisomal disorders. Neurochem. Res. 1999;24:187–197. doi: 10.1023/a:1022549618333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cox KB, Hamm DA, Millington DS, Matern D, Vockley J, Rinaldo P, Pinkert CA, Rhead WJ, Lindsey JR, Wood PA. Gestational, pathologic and biochemical differences between very long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency and long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency in the mouse. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2001;10:2069–2077. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.19.2069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kennedy ET, Bowman SA, Powell R. Dietary-fat intake in the US population. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 1999;18:207–212. doi: 10.1080/07315724.1999.10718853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Subar AF, Krebs-Smith SM, Cook A, Kahle LL. Dietary sources of nutrients among US children, 1989–1991. Pediatrics. 1998;102:913–923. doi: 10.1542/peds.102.4.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shen JJ, Matern D, Millington DS, Hillman S, Feezor MD, Bennett MJ, Qumsiyeh M, Kahler SG, Chen YT, Van Hove JL. Acylcarnitines in fibroblasts of patients with long-chain 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency and other fatty acid oxidation disorders. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2000;23:27–44. doi: 10.1023/a:1005694712583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Piper CM, Carroll PB, Dunn FL. Diet-induced essential fatty acid deficiency in ambulatory patient with type I diabetes mellitus. Diab. Care. 1986;9:291–293. doi: 10.2337/diacare.9.3.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carlson SE, Cooke RJ, Werkman SH, Tolley EA. First year growth of preterm infants fed standard compared to marine oil n − 3 supplemented formula. Lipids. 1992;27:901–907. doi: 10.1007/BF02535870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harding CO, Gillingham MB, van Calcar SC, Wolff JA, Verhoeve JN, Mills MD. Docosahexaenoic acid and retinal function in children with long-chain 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 1999;22:276–280. doi: 10.1023/a:1005502626406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duran M, Wanders RJ, de Jager JP, Dorland L, Bruinvis L, Ketting D, Ijlst L, van Sprang FJ. 3-Hydroxydicarboxylic aciduria due to long-chain 3-hydroxyacyl-coenzyme A dehydrogenase deficiency associated with sudden neonatal death: protective effect of medium-chain triglyceride treatment. Eur. J. Pediatr. 1991;150:190–195. doi: 10.1007/BF01963564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roe CR, Sweetman L, Roe DS, David F, Brunengraber H. Treatment of cardiomyopathy and rhabdomyolysis in long-chain fat oxidation disorders using an anaplerotic odd-chain triglyceride. J. Clin. Invest. 2002;110:259–269. doi: 10.1172/JCI15311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.den Boer ME, Wanders RJ, Morris AA, Ijlst L, Heymans HS, Wijburg FA. Long-chain 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency: clinical presentation and follow-up of 50 patients. Pediatrics. 2002;109:99–104. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.1.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Food and Nutrition Board, National Institute of Medicine. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein and Amino Acids (Macronutrients) 2002 doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(02)90346-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Harding CO, Gillingham M, Connor WE, Neuringer M, Weleber RG. Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) supplementation does not prevent retinal degeneration in LCHAD deficiency. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2002;25:71. [Google Scholar]